Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Psicológica

versão impressa ISSN 0870-8231versão On-line ISSN 1646-6020

Aná. Psicológica vol.37 no.3 Lisboa jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1645

Quality of sibling relationship and parental differential treatment in a sample of Portuguese adolescents

Qualidade do relacionamento entre irmãos e tratamento parental diferenciado numa amostra de adolescentes portugueses

Inês Carvalho Relva1, Madalena Alarcão2, Otília Monteiro Fernandes3, Sandra Graham-Bermann4

1Centro de Estudos Sociais, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal / Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Vila Real, Portugal

2Centro de Estudos Sociais, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

3Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Vila Real, Portugal

4University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

ABSTRACT

Siblings are extremely important in adolescent life. We intent to study how sibling attachment, parental differential treatment and the use of conflict tactics resolution in siblings relationship are related. In a sample of 192 Portuguese adolescents aged between 11 and 16 we applied Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment, sibling version; the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales – Sibling Version and the Sibling Inventory Differential Experience. The results show that an equal parental treatment are associated with positive way of solving conflicts between siblings; boys reported more distance from siblings than girls, and a negative sibling relationship seems to influence the occurrence of sibling violence. This study stresses the importance of parents and practitioners in promoting earlier closeness between siblings.

Key words: Differential treatment, Parents, Siblings, Attachment, Revised Conflict Tactics Scales – Sibling Version.

RESUMO

Os irmãos são extremamente importantes na vida do adolescente. Com este estudo tivemos por objetivo explorar de que modo estão relacionados a vinculação entre irmãos, o tratamento parental diferenciado e o uso de táticas resolução de conflito no relacionamento entre irmãos. Numa amostra de 192 adolescentes portugueses, 64.6% do sexo feminino, com idades compreendidas entre os 11 e os 16 anos, aplicou-se o Inventário de Vinculação na Adolescência (versão irmãos), as Escalas de Táticas do Conflito Revisadas (versão irmãos) e o Inventário de Experiências Diferenciadas entre Irmãos. Os resultados mostram que um tratamento parental igualitário está associado à maneira positiva de resolver os conflitos entre irmãos; o sexo masculino relatou maior distanciamento entre irmãos do que o sexo feminino, e uma relação negativa entre irmãos parece influenciar a ocorrência de violência entre estes. Este estudo enfatiza a importância de pais e profissionais de saúde promoverem precocemente a proximidade entre irmãos.

Palavras-chave: Tratamento diferenciado, Pais, Irmãos, Vinculação, CTS2-SP.

Introduction

Attachment is extremely important in human life. Its precursor, John Bowlby (1969) proposed that human beings survival, especially children, is ensured when the presence of an attachment figure is maintained. Thus, the attachment that the child sets (or not) in the family is extremely important in how he will see future situations that occur outside the family. Thus, babies with a secure attachment learn to rely on parental figures using them as a secure base to explore everything around them (Papalia, Olds, & Feldman, 2001). As Bank and Kahn (1997) argued “human beings cannot survive without a warm, predictable attachment to another person” (p. 27). Subjects with a secure attachment, develop positive feelings about themselves and others, while individuals with an insecure attachment demonstrate negative feelings about themselves and others (Hines & Malley-Morrison, 2005). In this line, Ainsworth (1980) suggested a causal relationship between abnormality in attachment to parents and the abuse of children.

Attachment research has focus namely in child primarily caretakers, and the term attachment it is normally used for affectional bonds between infants and their mother (Buist, Devović, Meeus, & Acan, 2004). In adolescence, and because it is a life cycle period critical, others relationships are needed to explore, such siblings. Indeed different persons can serve as attachment figures, such as parents, siblings, grandparents (Cassidy, 2008; Cicirelli, 1995) teachers (Howes, 1999) and peers (Mota & Matos, 2013). In 1997 Trinke and Bartholomew conducted a study with 223 university students that intended to examine the characteristics of attachment hierarchies in young adult. The authors found that most young adults have multiple attachment figures including siblings. However, studies about sibling attachment during adolescence (Noel, Francis, & Tilley, 2018; Whiteman, McHale, & Soli, 2011) and during adulthood seem to be scarce (Tibbetts & Sharfe, 2015). Recently, in a study with 220 participants, with ages ranged 18 to 55, with at least one leaving sibling Brumbaugh (2017) found that greater attachment security was related with having more siblings.

Bank and Kahn (1997) have argued that “siblings attachment can play an important role in early development of child’s personality” (p. 27). Indeed, sibling relationship is so important that can influence even when siblings are separately (Cicirelli, 1995). Sibling relationship seems to be very important, since it is considered the longest relationship in human life (Bank & Kahn, 1997) and because of the variety of roles they can play “friend, competitor, caregiver/caregivee, teacher/learner, manager/ manage” (Buhrmester, 1992, p. 21) and also as a buffer in stressfull situations (Cummings & Smith, 1993).

Quality of sibling relationship seems to have an influence on several aspects of children and adolescents’ life. In a study with 86 two-parent families with at least two children, Hidman, Riggs, and Hook (2013) found that sibling relationship quality directly contributed to behavior problems in children.

A negative aspect of sibling relationship it is the occurrence of sibling violence. Indeed this phenomenon it is highly prevalent during adolescence (Lopes, Relva, & Fernandes, 2017; Relva, Fernandes, Alarcão, & Martins, 2014; Roscoe, Goodwin, & Kennedy, 1987) and it is probably the most prevalent form of family violence. The real extension of sibling violence it still unknown, however it seems that scientific community started to pay more attention to this social problem. Some sibling violence consequences are related with psychopathologic problems such as anxiety (Lopes et al., 2017; Mackey, Fromuth, & Kelly, 2010) but also with peer’s aggression (Criss & Shaw, 2005; Johnson et al., 2015) insecurity and feelings of incompetence (Bordin, Paula, Nascimento, & Duarte, 2006). This phenomenon remains poorly understood by families, clinicians and society in general. The campaigns of prevention are focusing namely in marital violence and parent-to-child violence, ignoring this form of violence. Parents often minimized this kind of behaviors among siblings (Tucker, Finkelhor, Turner, & Shattuck, 2013). Also coerced secrecy and fear of family disruptions (Caspi, 2012), and reluctance in report the aggressive sibling to authorities (Caffaro & Conn-Caffaro, 2005) are some explanations why sibling violence prevalence remains underreported. Recently in a study with 392 college students, aged between 17 and 55, Tibbetts and Sharfe (2015) found that fearful sibling attachment was a significant predictor of conflict.

Another important aspect in adolescent life is parental differential treatment perception. Since in 1985, Daniels, Dunn, Furstenberg and Plomin conducted the first study analyzing the relation between environmental differences within the family and differences between siblings, this variable seems to win some importance. Studies have been conducted regarding the association of parental differential treatment with different sibling issues namely negative emotionality (Brody, Stoneman, & McCoy, 1992) justice perception of parental treatment (Kowal, Kramer, Krull, & Criok, 2002), child’s externalizing behavior (Meunier et al., 2012) and the effect of parental differential treatment sibling relationship with one disabled child (Wolf, Fisman, Ellison, & Freeman, 1998).

Indeed, more than the way that parents treats their children, the way this it is understood by children seems to be more important.

Finally, regarding gender and sibling relationship there seems to have some differences. Soysal (2016) recently have found that in a sample of high schools students aged between 15 and 17 that siblings from the same sex reported more positive attitudes towards their siblings when compared with those who had siblings from different sex.

We didn’t find studies associating sibling attachment, differential parental treatment and the use of conflict tactics scales between siblings. Additionally in Portugal the research regarding this variables is scarce (Geraldes, Soares, & Martins, 2013) so this study intend to contribute to a better comprehension by: (a) exploring the association between quality of siblings attachment, the use of conflict tactic resolution between siblings and paternal differential treatment (b) exploring if sex, parental differential treatment and conflict tactic resolution are predictors of sibling attachment; and finally (c) analyzing sex differences according to quality of siblings attachment, different tactics resolution and parental differential treatment.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 192 adolescents, with siblings, aged between 11 and 16 years old (M=13.51; SD=1.05) and more than half (64.6%) were females. The adolescents attended the high school, 173 (37.4%) were in the 10th grade, 121 (26.1%) studied in the 11th grade and 169 (36.5%) attended the 12th grade. As for the number of siblings, 69.5% had only one sibling, while 22.7% had two, 5% had three siblings, 1.1% had four, .9% had five and .8% had six or more siblings.

Instruments

Socio-Biographical Questionnaire (SBQ). The SBQ is a questionnaire based on Social Environment Questionnaire of Toman (1993), adapted for this investigation by Fernandes e Relva (2013). The questionnaire inquires the individuals about the subject (gender, age, place of birth, grade, diseases and hospitalizations), their siblings (number of siblings, type, gender, age and diseases or disabilities) and their parents (age, socio-economic status and marital status).

The Sibling Inventory Differential Experience (SIDE; Daniels & Plomin, 1985, version translated by Fernandes & Relva, 2012) allows us to evaluate the experiences of subject at siblings interaction, differential treatment by parents (mother and father separately), characteristics of the pairs and individual specific events. Each item presents the five answer choices: 1 – “more times with my brother/sister”; 2 – “slightly more times with him/her”; 3 – “equal”; 4 – “slightly more often with me”; 5 – “many more times with me.” For the present study only differential parental treatment was used (control and affectional scale), with Cronbach’s alpha of .69 and .82 for control scale, mother and father respectively and Cronbach’s alpha of .78 and .91 for affectional scale, also mother and father respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed appropriate adjustment indices for mother χ2(23)=60,768; p=.000; Ratio 2.642=; CFI=.93; RMR=.018 and RMSEA=.09 and for father χ2(22)=47,876; p=.001; Ratio=2.176; CFI=.098; RMR=.013 and RMSEA=.08.

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2-SP Sibling Version; Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1995). The CTS2-SP consists of 39 items in double, perpetration and victimization dimensions, divided five scales: (1) Negotiation (6 items), (2) Psychological Aggression (8 items), (3) Physical Assault (12 items), (4) Sexual Coercion (7 items) and (5) Injury (6 items), however given the objective of the present study, we have excluded the sexual coercion scale. In this version one item was excluded in psychological aggression (cf. Fernandes, Relva, Rocha, & Alarcão, 2016). The CTS2-SP questions were presented in relationship pairs (experiences of received and expressed). The scale of response reflects the frequency of each behavior over a period of time (0) this has never happened, (1) once a year, (2) twice a year, (3) 3-5 times a year, (4) 6-10 times a year, (5) 11-20 times a year, (6) more than 20 times a year, and (7) not that year, but it happened. The CTS2-SP was adapted by Relva, Fernandes and Costa (2013) and in this version psychometric proprieties was found to be adequate. In this sample we only used perpetrations scales, and four dimensions: psychological aggression, physical assault, injury and negotiation. For psychological aggression the alpha was .87; physical assault with an alpha of .96; injury with an alpha of .97 and for negotiation the alpha was .72. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed appropriate adjustment indices for perpetration scale χ2(32)=84,655; p=.000; Ratio=2.645; CFI=.98; RMR=.194 and RMSEA=.09.

The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), it is a multifactorial self-assessment tool developed in the evaluation of the positive and negative perceptions of adolescents in affective and cognitive behavioral dimensions of attachment relation -ships with father, mother and friends (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987, translated for Portuguese by Neves, Soares, & Silva, 1999) and also for siblings (Buist, Deković, Meeus, & Aken, 2002; validated for the Portuguese population by Geraldes et al., 2013). Parents and friend’s subscale assesses three major dimensions: trust, communication and alienation. Sibling subscale assesses closeness and distance dimensions. Each item is priced using a Likert 5-point scale (1 – never or almost never to 5 – always or almost always). On this study only the sibling version was used.

Concerning internal consistency of IPPA – Sibling version, the results were adequate: for closeness were .93; and for distance .77. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed appropriate adjustment indices siblings version χ2(17)=30.484; p=.023; Ratio=1.793; CFI=.98; RMR=.038 and RMSEA=.06.

Procedure

Data was collected in several schools in northern Portugal. After institutional permissions, it was undertaken authorization applications to parents of adolescents. The instruments were held in the classroom, in group context, and takes about 25 minutes to fulfill. The study goals were presented, providing the necessary instructions for filling out the instruments and evidencing voluntary participation, as well as the responses confidentiality and anonymity. When completed the questionnaires, the participants delivered them to the researcher.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences – SPSS, version 22.0, and for realization of the psychometric properties of the instruments we used the Structural Program Equation Modeling Software – EQS for Windows, version 6.1. Psychometric analyzes were conducted using the Cronbach alpha and confirmatory factor analysis. The Skeweness and Kurtosis values allow us to use parametric tests. Also t-test was conducted also conducted with the aim of explore differential analysis of conflict tactics perpetration, parents and siblings quality of attachment by gender.

A hierarchical multiple regression was realized, for which it was necessary to codify the variable gender as a dummy variable, assigning zero to the female and the value one to male.

Results

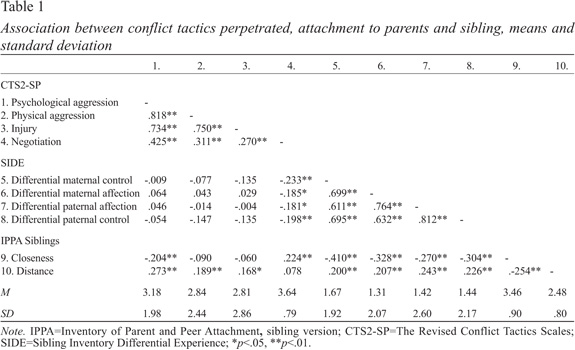

Association between conflict tactics scales, attachment to sibling and parental differential treatment, means and standard deviation

Correlation analysis was conducted, and results shows a significant correlation between variables (Table 1). Perpetration of psychological aggression have a significant and positive correlation with siblings distance (r=.273, p<.01); and a significant and negative correlation with sibling closeness (r=-.204, p<.01). Perpetration of physical aggression was positively correlated with siblings distance (r=.189, p<.01). Concerning perpetration of injury this variable was positively correlated with siblings distance (r=.168, p<.05). The use of negotiation for sibling conflict resolution have a significant and negative correlation with differential maternal control (r=-.233; p<.01), with differential maternal affection (r=-.185; p<.05), with differential paternal control (r=-.198; p<.01), with differential paternal affection (r=-.181; p<.01); and finally a significant and positive correlation with siblings closeness (r=.224, p<.01).

Regarding differential maternal treatment, control scale have a significant and positive correlation with siblings distance (r=.200, p<.01); and a significant and negative correlation with sibling closeness (r=-.410, p<.01); and affection scale have a significant and positive correlation with siblings distance (r=.207, p<.01); and a significant and negative correlation with sibling closeness (r=-.328, p<.01).

Concerning differential paternal treatment, control scale have a significant and positive correlation with siblings distance (r=.226, p<.01); and a significant and negative correlation with sibling closeness (r=-.304, p<.01); and affection scale have a significant and positive correlation with siblings distance (r=.243, p<.01); and a significant and negative correlation with sibling closeness (r=-.270, p<.01).

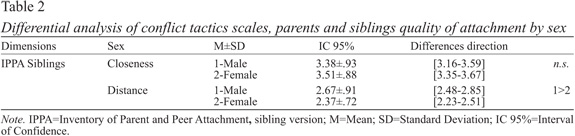

Differential Analysis of conflict tactics scales, parents and siblings quality of attachment by sex

A t-test analysis was conducted (Table 2) between the variables of conflict tactics resolution, sibling attachment and differential parental treatment according to sex. The results addressed one significant difference regarding siblings distance t(190)=-.247; p=.023; with IC 95% [-.55, .04], where males (M=2.48; SD=2.85) have higher levels of siblings distance when compared with females (M=2.23; SD=2.51).

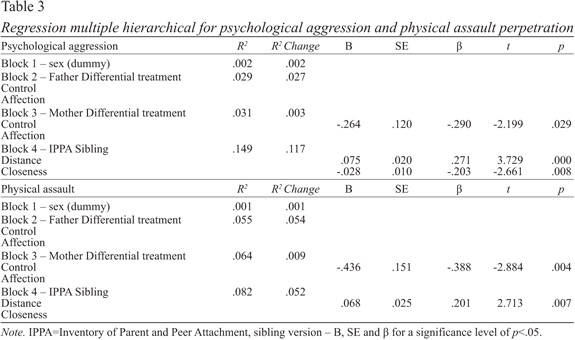

Prediction role of sex, of parental differential treatment and sibling’s attachment on psychological aggression

Multiple regression analysis was conducted introducing four blocks, namely, sex, parental differential treatment and conflict tactics scales perpetrated. Sex variable was recoded in dummy (1 – female and 0 – male).

Concerning multiple regression analysis to psychological aggression four blocks were introduced. Only block 4, siblings attachment presented a significant contribution F(7,184)=4.594, p=.000, explain 14.9% of total variance (R2=.149) and explaining individually 11.7% of model variance (R2change=.117). Analyzing each one of the independent variables of blocks results show that three variables have a significant contribution (p<.05: father differential control (β=-.290), sibling closeness (β=-.203) and sibling distance (β=.271) (see Table 3).

Prediction role of sex, of parental differential treatment and sibling’s attachment on physical assault

Regarding multiple regression analysis to physical (Table 3), block 2, father differential had a significant contribution F(3,188)=3.657, p=.014, explain 5.5% of total variance (R2=.055), presenting an individual contribute of 5.4% (R2change=.054). Looking at block 3, mother differential treatment had also a significant contribution F(5,186)=2.552, p=.029, explain 6.4% of total variance (R2=.064), presenting an individual contribute of .9% to the variance of the model (R2change=.009). Finally, block 4, siblings attachment presents a significant contribution F(7,184)=3.441, p=.002, explain 8.2% of total variance (R2=.082) and explaining individually 5.2% of model variance (R2change=.052). Analyzing each of independent variables of blocks the results show that the two variables have a statistically significant contribution with less than .05: father differential control (β=-.388) and sibling distance (β=.207).

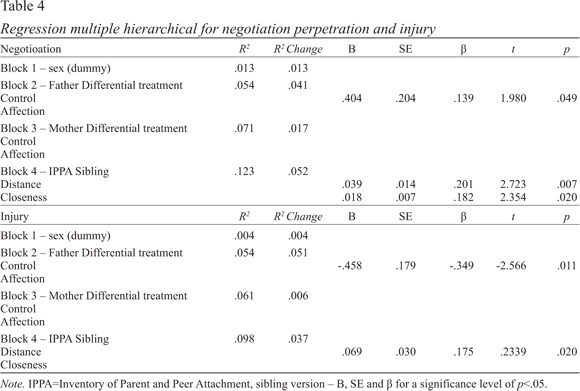

Prediction role of sex, of parental differential treatment and sibling’s attachment on injury

Regarding multiple regression analysis to injury four blocks were introduced (Table 4), looking at block 3, mother differential treatment had a significant contribution F(5,186)=2.404, p=.039, explain 6.1% of total variance (R2=.061), presenting an individual contribute of .6% to the variance of the model (R2change=.006). Finally, block 4, siblings attachment also presents a significant contribution F(7,184)=2.842 p=.008, explain 9.8% of total variance (R2=.098) and explaining individually 3.7% of model variance (R2change=.037). Analyzing each one of independent variables of blocks results show that two variables have a statistically significant contribution with less than .05: father differential control (β=-.349) and sibling distance (β=.175).

Prediction role of sex, parental differential treatment and sibling’s attachment on use of negotiation

Concerning multiple regression analysis to use of negotiation four blocks were introduced (Table 4). Block 2, father differential treatment had a significant contribution F(3,188)=3.577, p=.015, explain 5.4% of total variance (R2=.054), presenting an individual contribute of 4.1% (R2change=.041). Looking at block 3, mother differential treatment had also a significant contribution F(5,186)=2.404, p=.017, explain 7.1% of total variance (R2=.071), presenting an individual contribute of 1.7% to the variance of the model (R2change=.017). Finally, block 4, siblings attachment presented a significant contribution F(7,184)=3.695, p=.001, explain 12.3% of total variance (R2=.123) and explaining individually 5.2% of model variance (R2change=.052). Analyzing each of independent variables of blocks the results show that two variables have a statistically significant contribution with less than .05: sex block (β=.139) with a female contribution, sibling closeness (β=.182) and sibling distance (β=.201).

Discussion

This study intended to explore the way adolescents resolve conflicts with siblings and how this is related with sibling’s attachment and parental differential treatment. It was also explored how the way adolescents see mother and father differential treatment and conflicts tactics resolution predicts quality of sibling relationship.

Analyzing the results, and as expected, the use of psychological aggression as a way to resolve conflict with siblings was positively associated with siblings distance. Psychological aggression between siblings may include tease, ridicularization, intimidation, provocation, degradation, name-calling (Wiehe, 1997). In a study with 233 university students, Teven, Martinn and Neupauer (1998) found that verbal aggression can lead to negative relational outcomes and can lead to reduction in sibling’s communication. Additionally, verbal aggression it is associated with a distant relationship between siblings and as Whipple and Finton (1995) argued can lead to harmful effects on families. As expected, psychological aggression was negatively associated with siblings closeness. Recently in a study with 448 participants with ages between 18-92, Rittenour, Myers and Brann (2007) found that sibling commitment was associated with communication-based emotional support. Indeed, it seems that siblings who are more committed with each other tend to have a more positive communication without aggression. In this line, the results also suggest that not only psychological aggression may contribute to siblings distance, but other forms of sibling violence, such as physical assault and injury. Although sibling relationship is an obligation or forced relation (Rittenour et al., 2007), negative ways of solving conflicts may contribute to their separation. However, family structure may allow the frequency of conflict (Furman & Burhmester, 1985) because they live in the same house. Also Graham-Bergmann (1991) found in a sample of 40 pairs of siblings ages ranged between 9 and 14 years old, in a study that intend to assess self-ratings, self-perceptions, and sibling behavior, that perceptions of differences were associated with conflicts between siblings.

Regarding the use of negotiation for resolving conflicts with siblings it is negatively associated with parental differential treatment, for both parents and also for both scales, affectional and control. This means that sibling’s relationship it is appraised as more positive when adolescents tend to see parental treatment as more egalitarian. The opposite also happens. Some studies have shown that parental favoritism can lead to negative behaviors between siblings, namely violence (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). Sholte, Engels, Kemp, Harakeh and Overbeek (2007) in a sample of 416 sibling pair where the younger sibling aged between 13 and 15 and the older sibling aged between 14 and 17, have found that young siblings that felt they were treated differently way by their mothers, became more vandalistic and violent in the next year.

Another expected result was differential parental treatment, both affection and control scales, for both parents were positive associated with sibling’s distance and were negative associated with sibling closeness. Indeed, and following the previous idea, paternal differential treatment seems associated with negative sibling relationship conducting to distance and less closeness. In a recent study with 117 families with a child referred as having externalizing problems Meunier et al. (2012) found that a less favorable parental treatment was associated with a poorer quality of sibling relationship.

When gender was considered, as expected, males reported more sibling distance than females. This result is consistent with others studies. For example, Buhrmester (1992) found that females reported more intimacy when compared with males. This may be associated with a decreased in rates of intimate disclosure and affection between siblings across adolescence (Buhrmester, 1992) namely because other significant may assume importance such as peers and romantic relationship. Also Buist et al. (2002) found in a sample of 288 families, that adolescent girls reported higher attachment to sisters than adolescent boys, showing that development of attachment it is influenced by gender.

Finally, and looking for the least analysis, results shows that sex also predicts the use of negotiation to solve a conflict with a sibling. Females used reported more used of negotiation as a way to solve conflicts. This result is consistent with previous research (cf. Lopes et al., 2017). Another expected result was that sibling closeness predicts the use of negotiation, indeed it is expected that siblings more closed to each other used more adequate ways of solving problems. In 1998, in a sample of 34 of fifth and sixth grade, Rinaldi and Howe found that warmth sibling relationship was associated with prosocial behaviors and more constructive strategies use.

The results also point out that siblings distance positively predicts the use of negotiation and sibling’s closeness negatively predicts the use of negotiation. Indeed, this form of problem solving seems to be the more used in sibling relationship (Relva et al., 2014). However, sibling’s distance, as expected, predicts the use of negative ways of solving conflict, injury, psychological aggression and physical assault, some explanations were already presented above.

Differential affection by both parents, in this sample, doesn’t predict the occurrence of sibling violence. This means that other variables should be considered. If sibling relationship is positive and warm, the influence of differential parental treatment it is reduced (Sholte et al., 2007). Another explanation may be that we were in the presence of the favorite child. Noller (2005) argued that “the quality of the relationship is affected by differential treatment it seems that it is the disfavored sibling’s behavior that is particularly affected” (p. 18). One result not expected was that an equal treatment and equal control by fathers seems to have influence in occurrence of sibling violence. Indeed, in adolescence it seems that youngs spend more time with friends and less with families (Papalia et al., 2001). Additionally, they need to have their own identity and be treated differently than their sibling. Fathers, namely in occidental societies, needs to renegotiate the parent-child relations and allow that adolescent participate in family decisions.

Discussion

Limitations, practical implications and future research

Finally, this study has some limitations that should be considered. First, the characteristics of the sample are not representative of adolescent’s Portuguese population; second, we only collected data from participant’s perspective.

Although the limitations presented, the study of this issue is extremely important. The results pointed out the need to promote autonomy and identity formation of adolescents, namely in families, treating children differently. Future studies should collect data from parent perspective, it would be important to consider increasing the size of the sample, and also develop qualitative research that will give us information concerning motivation, causes and consequences. Other questions such as type of sibling, family configurations (e.g., children institutionalized, divorced families), familiar problems idem unemployed, psychopathological problems, should be considered, because they can have an influence on quality of sibling relationship. Further studies addressing sibling’s relationships are needed namely those exploring conflicts tactics resolution and how it relates with other familiar subsystems such as parent-to-child and parent-to-parent. The perception of justice of differential paternal treatment should also be explored.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1980). Attachment and child abuse. In G. Gerbner, C. J. Ross, & E. Zigler (Eds.), Child abuse: An agenda for action (pp. 35-47). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427-54. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939 [ Links ]

Bank, S. P., & Kahn, M. D. (1997). The sibling bond (15th anniversary ed.). New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Bordin, I. A. S., Paula, C. S., Nascimento, R., & Duarte, C. S. (2006). Severe physical punishment and mental health problems in an economically disadvantaged population of children and adolescents. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 28, 290-296. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462006000400008 [ Links ]

Brody, G. H., Stoneman, Z., & Mccoy, J. K. (1992). Associations of maternal and paternal direct and differential behavior with sibling relationships: Contemporaneous and longitudinal analyses. Child Development, 63, 82-92. [ Links ]

Buhrmester, D. (1992). The developmental courses of sibling and peer relationships. In F. Boer & J. Dunn (Eds.), Children’s sibling relationships: Developmental and clinical issues (pp. 19-40). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Buist, K., Deković, M., Meeus, W., & Aken, A. (2002). Development patterns adolescent attachment to mother, father and sibling. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 167-176. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1015074701280 [ Links ]

Buist, K., Deković, M., Meeus, W., & Aken, M. (2004). Attachment in adolescence: A social relations model analysis. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 826-850. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0743558403260109 [ Links ]

Brumbaugh, C. C. (2017). Transferring connection: Friend and sibling attachment’s importance in the lives of singles. Personal Relationships, 24, 534-549. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pere.12195

Caffaro, J. V., & Conn-Caffaro, A. (2005). Treating sibling abuse families. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10, 604-623. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2004.12.001 [ Links ]

Caspi, J. (2012). Sibling aggression: Assessment and treatment. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Cassidy, J. (2008). The nature of the child’s ties. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications.

Cicirelli, V. C. (1995). Sibling relationships across the life span. New York: Plenum Press. [ Links ]

Criss, M. M., & Shaw, D. S. (2005). Sibling relationships as contexts for sibling training in low-income families. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 592-600. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.592 [ Links ]

Cummings, E., & Smith, D. (1993). The impact of anger between adults on siblings’ emotions and social behavior. Journal of Child Psychology Psychiatry, 34, 1425-1433.

Daniels, D., & Plomin, R. (1985). Differential experience of siblings in the same family. Developmental Psychology, 21, 747-760. [ Links ]

Daniels, D., Dunn, J., Furstenberg, F. F. Jr., & Plomin, R. (1985). Environmental differences within the family adjustment differences within pairs of adolescent siblings. Child Development, 56, 764-774. [ Links ]

Fernandes, O. M., & Relva, I. C. (2013). Questionário sociobiográfico – QSB (manuscrito não publicado). Vila Real: Departamento de Educação e Psicologia da Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Portugal.

Fernandes, O. M., Relva, I., Rocha, M., & Alarcão, M. (2016). Estudo da validade de construto das Revised Conflict Tactics Scales – Versão Irmãos. Motricidade, 12, 69-82. Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.6182

Furman, W., & Burhmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of qualities of siblings relationships. Child Development, 56, 448-461. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1129733

Geraldes, R., Soares, I., & Martins, C. (2013). Vinculação no contexto familiar: Relações entre os cônjuges, entre pais e filhos adolescentes e entre irmãos. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 26, 799-808. Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722013000400021 [ Links ]

Graham-Bermann, S. (1991). Siblings in dyads: Relationships among perceptions and behavior. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 152, 207-216. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1991.9914667 [ Links ]

Hines, D., & Malley-Morrison, K. (2005). Family violence in the United States: Defining, understanding and combating abuse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Hidman, J. M., Riggs, S. A., & Hook, J. R. (2013). A contribution of executive, parent-child, and sibling subsystems to children’s psychological functioning. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 2, 294-308. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034419

Howes, C. (1999). Attachment relationships in the context of multiple caregivers. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 671-687). New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Johnson, R., Duncan, D., Rothman, E., Gilreath, T., Hemenway, D., Molnar, B., & Azrael, D. (2015). Fighting with siblings and with peers among urban high school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30, 2221-2237. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260514552440 [ Links ]

Kowal, A., Kramer, L., Krull, J., & Crick, N. (2002). Children’s perceptions of fairness of parental preferential treatment and their socioemotional well-being. Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 297-306. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.16.3.297

Lopes, P., Relva, I. C., & Fernandes, O. M. (2017). Psychopathology and sibling violence in a sample of Portuguese adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12, 11-21. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0194-4 [ Links ]

Mackey, A. M., Fromuth, M. E., & Kelly, D. B. (2010). The association of sibling relationship and abuse with later psychological adjustment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 955-968. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260509340545 [ Links ]

Meunier, J., Roskam, I., Stievenart, M., Moortele, G., Browne, D., & Wade, M. (2012). Parental differential treatment, child’s externalizing behavior and siblings relationships: Bridging links with child’s perception of favoritism and personality, and parent’s self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29, 612-638. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407512443419

Mota, C. P., & Matos, P. (2013). Peer attachment, coping and self-esteem in institutionalized adolescents: The mediating role of social skills. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28, 87-100. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0103-z [ Links ]

Neves, L., Soares, I., & Silva, M. C. (1999). Inventário da vinculação na adolescência – IPPA. In M. R. Simões, M. Gonçalves, & L. S. Almeida (Eds.), Testes e provas psicológicas em Portugal (Vol. 2). Braga: APPORT/SHO.

Noel, V., Francis, S., & Tilley, M. (2018). An adapted measure of sibling attachment: Factor structure and internal consistency of the Sibling Attachment Inventory in Youth. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 49, 217-224. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10578-017-0742-z [ Links ]

Noller, P. (2005). Sibling relationships in adolescence: Learning and growing together. Personal Relationships, 12, 1-22. [ Links ]

Papalia, D. E., Olds, S. W., & Feldman, R. D. (2001). O mundo da criança (8ª ed.). Lisboa: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Relva, I. C., Fernandes, O. M., Alarcão, M., & Martins, A. (2014). Estudo exploratório da violência entre irmãos em Portugal. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 27, 398-408. Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1678-7153.201427221 [ Links ]

Relva, I. C., Fernandes, O. M., & Costa, R. (2013). Psychometric Properties of Revised Conflict Tactics Scales: Portuguese Sibling Version (CTS2-SP). Journal of Family Violence, 28, 577-585. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9530-0 [ Links ]

Rinaldi, C., & Howe, N. (1998). Siblings reports of conflict and the quality of their relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 44, 404-422. [ Links ]

Rittenour, C., Myers, S., & Brann, M. (2007). Commitment and emotional closeness in the sibling relationship. Southern Communication Journal, 72, 169-183. [ Links ]

Roscoe, B., Goodwin, M. P., & Kennedy, D. (1987). Sibling violence and agonistic interactions experienced by early adolescents. Journal of Family Violence, 2, 121-137. [ Links ]

Sholte, S., Engels, R., Kemp, R., Harakeh, Z., & Overbeek, G. (2007). Differential parental treatment, sibling relationships and delinquency in adolescence. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 36, 661-671. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9155-1 [ Links ]

Soysal, F. (2016). A study on sibling relationships, life satisfaction and loneliness level of adolescents. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(4), 58-67. [ Links ]

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1995). Conflict Tactics Scales form: CTS2-SP. In M. Straus (Ed.), Handbook of Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS): Including revised versions of CTS2 and CTS2 PC (pp. 61-64). Durham, NH: Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire. [ Links ]

Teven, J. J., Martinn, M. M., & Neupauer, N. C. (1998). Sibling relationships: Verbally aggressive message and their effect on relational satisfaction. Communication Reports, 11, 179-186. [ Links ]

Tibbetts, G., & Scharfe, E. (2015). Oh, brother (or sister)!: An examination of sibling attachment, conflict, and cooperation in emerging adulthood. Journal of Relationships Research, 6(8), 1-11. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/jrr.2015.4 [ Links ]

Toman, W. (1993). Family constellation: Its effects on personality and social behavior. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Trinke, S. J., & Bartholomew, K. (1997). Hierarchies of attachment relationships in young adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 14, 603-625. [ Links ]

Tucker, C. J., Finkelhor, D. F., Turner, H., & Shattuck, A. (2013). Association of sibling aggression with child and adolescent mental health. Pediatrics, 132, 79-84. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3801 [ Links ]

Whipple, E., & Finton, S. (1995). Psychological maltreatment by siblings: An unrecognized form of abuse. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 12, 135-146. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01876209 [ Links ]

Whiteman, S., McHale, S., & Soli, A. (2011). Theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 3, 124-139. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2011.00087.x [ Links ]

Wiehe, V. R. (1997). Sibling abuse: Hidden physical, emotional, and sexual trauma (2nd ed.). California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Wolf, L., Fisman, S., Ellison, D., & Freeman, T. (1998). Effect of sibling perception of differential parental treatment in sibling dyads with one disabled child. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 1317-1325. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199812000-00016 [ Links ]

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Inês Carvalho Relva, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Quinta de Prados, 5001-801 Vila Real, Portugal. E-mail: irelva@utad.pt

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Submitted: 05/09/2018 Accepted: 11/12/2018