Bullying has been described as a repeated aggressive behavior, intended to harm another student or group of students (El-ony et al., 2023), particularly those perceived as weaker or having less power than the perpetrator(s) (Salmivalli & Peets, 2018). It is a common phenomenon worldwide affecting around 50% of children (Lyznicki et al., 2014).

Traditionally, bullying has been classified into four basic types of abuse: physical (hitting, kicking, pushing, spitting, stealing, damaging others’ properties), verbal (threatening, teasing, insulting, assigning nicknames, taunting, intimidating, making remarks and inappropriate sexual comments), relational (direct or indirect promoting social exclusion, rumor spreading), and cyberbullying (via digital or social media) (Çalışkan et al., 2019). Previous findings indicate that there is an overlap between bullying forms (Johansson & Englund, 2021; Zhang et al., 2014). Nevertheless, it is also important to differentiate them, as they have been shown to be distinctive constructs associated to several correlates (Dukes et al., 2010; Travlos et al., 2018).

The type of bullying seems to be influenced by the age of both the perpetrator and the victim. In early childhood, physical bullying is more prevalent because children have not yet developed their language skills (Coyne et al., 2010). As language skills develop, verbal bullying becomes more common. When boys and girls start forming more peer relationships, indirect forms of bullying, such as relational bullying, become increasingly frequent. This type is particularly common during puberty, a time when peer acceptance is crucial for an adolescent’s psychosocial development (Berger, 2007), making bullying more subtle and complex. Finally, cyberbullying begins when children gain access to digital devices and social media, a trend that is occurring at increasingly younger ages (Barlett & Coyne, 2014).

School is the primary setting for bullying, as it is where most interactions and relationships among children and adolescents occur (Santos & Faro, 2018). A study by Oliboni et al. (2019) concluded that bullying most frequently takes place in the classroom and during recess.

Research aimed at understanding the factors associated with bullying has investigated various sociodemographic, psychological, and contextual aspects, albeit often in isolation, that can help explain the phenomenon. On a more personal dimension, psychological factors related to both aggressors and victims have been highlighted. For aggressors, the following factors have been reported: low emotional regulation (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014), little empathy for the victim (Caravita et al., 2009; Dodaj et al., 2013), high self-esteem (Nakman et al., 2023; Olweus, 1991), but also low self-esteem (Cénat et al., 2014; Estévez et al., 2018), low life satisfaction, and also high life satisfaction (Cañas et al., 2020; Rezapour et al., 2019; Shetgiri et al., 2015).

Regarding the victims’ psychological factors, low self-esteem (Cantini, 2004; van Geel et al., 2018), depression (Estévez & Jiménez, 2015; Klomek et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2023), self-harm behavior and suicide ideation (Obando et al., 2018; Pedreira-Massa, 2019), anxiety (Coelho & Romao, 2018), suicide (Buelga et al., 2022; Nagamitsu et al., 2020) and low life satisfaction (Callaghan et al., 2015; Estévez & Jiménez, 2015; Weng et al., 2017) have been reported. Unfortunately, bullying can be lethal (Berger, 2007; Olweus, 1993).

Among the listed correlates, self-esteem and life satisfaction merit particular attention due to their inconclusive results, especially concerning aggressive behavior. This underscores the importance of conducting further research to uncover differences in self-esteem and life satisfaction between victims and bullies compared to non-victims and non-bullies.

Self-esteem refers to the evaluation individuals make of themselves, which can be positive or negative, based on internalized social judgments regarding their perceived competence and value (Mosquera & Stobäus, 2006). Several authors suggest that bullying behavior impacts the self-esteem of both victims (Bandeira, 2009; Cantini, 2004; Cénat et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2014; Mota et al., 2024; van Geel et al., 2018) and aggressors (Choi & Park, 2018; Estévez et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2023; Mota et al., 2024; Nakman et al., 2023). Based on two meta-analyses of longitudinal studies on peer victimization and self-esteem, van Geel et al. (2018) concluded that peer victimization can have long-lasting negative effects on self-esteem. Conversely, low self-esteem may predispose children to becoming victims, suggesting a cyclical relationship between self-esteem and peer victimization. The authors propose that victimization may reduce self-esteem as children internalize negative peer appraisals.

On the other hand, studies investigating the self-esteem of aggressors remain inconclusive, as previously mentioned. Some researchers have found a link between low self-esteem and aggressive behavior (Choi & Park, 2018; Estévez et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2023; Mota et al., 2024; Nakman et al., 2023). However, other studies challenge the traditional view of low self-esteem among perpetrators, suggesting instead feelings of self-worth among aggressors (Nakman et al., 2023; Olweus, 1991). A recent systematic review by Agustiningsih et al. (2023) demonstrated that self-esteem can have direct negative effects on victimization and cyber-victimization. Conversely, students with high self-esteem at the start of the school year were found to be more likely to engage in bullying behavior as they matured.

Another psychological variable identified as an important correlate of bullying behavior, albeit controversial, is low life satisfaction. Life satisfaction reflects cognitive and affective evaluations of one’s life based on personal standards (Diener et al., 2002).

There is considerable recent evidence suggesting the adverse effects of school bullying victimization on life satisfaction (Arnarsson et al., 2020; Chai et al., 2020; Salazar, 2021; Yang et al., 2021). Serra-Negra et al. (2015), in a cross-sectional study involving 366 Brazilian adolescents aged 13 to 15 years, found that aggressors also exhibit low levels of personal satisfaction. Additionally, Estévez et al. (2018) noted that aggressors of both genders display symptoms of depression, perceived stress, feelings of loneliness, low self-esteem, and reduced life satisfaction.

Conversely, some researchers have found that aggressors report high levels of life satisfaction (Cañas et al., 2020; Rezapour et al., 2019). It has been suggested that bullies’ high life satisfaction may stem from their popularity, high self-esteem, and strong social skills (Rezapour et al., 2019; Shetgiri et al., 2015).

Finally, meta-analytic studies provide robust evidence that men tend to have higher self-esteem than women. This disparity emerges in adolescence, persists through early and middle adulthood, and then diminishes in old age (Casale, 2020). Sex differences have also been observed in life satisfaction. In another meta-analytic study, Chen et al. (2020) found a slight but significant difference favoring male children and adolescents in their levels of life satisfaction.

The present study seeks to investigate whether students who have already been victims of bullying and students who have already been bullies differ in terms of self-esteem and life satisfaction from those who have never been victims or bullies, controlling for the effects of the sex covariate.

Based on the above discussion, we have postulated three hypotheses, as follows: (1) Victims of all forms of bullying will have lower levels of self-esteem than non-victims, controlling for sex. (2) Victims of all forms of bullying will have lower life satisfaction scores than non-victims, controlling for sex. (3) Bullies will have lower life satisfaction than non-bullies, controlling for sex. Due to the inconclusive results, we did not formulate hypotheses regarding the association between aggressive bullying behavior and self-esteem.

Method

Participants

A total of 194 students participated in the study: 119 (61.3%) female and 75 (38.7%) male, with an average age of 17.46 years (SD=1.26; range: 15 to 21 years). They were enrolled in integrated courses at the Federal Institute of Science and Technology in Bahia: 102 in the buildings course, 47 in the informatics course, and 45 in the environment course. The sample size calculation was based on the total enrollment of 629 students across these courses. Considering a population size (N), a 5% margin of error, and a 90% confidence level, a minimum of 191 participants was required. A power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007) to determine the statistical power for our ANCOVA. The analysis was based on the following parameters: an effect size (f) of 0.25 (medium effect size), an alpha level (α) of 0.05, a total sample size of 194 participants, 2 groups, and 1 covariate. Using these parameters, the power analysis indicated that the study has a power of 0.96, which is considered to be a high level of power (Cohen, 1988). This suggests that our study is well-powered to detect medium effect sizes for the ANCOVA.

Materials

In this study, four scales were used in addition to the sociodemographic questionnaire: Sociodemographic and course-related questionnaire: Comprising 15 questions covering information related to age, sex, race/ethnicity, mother’s and father’s education level, self-declared social class, family income, religion, living arrangements, and course-related details.

Bullying victimization scale (BVS): This scale was developed by Souza and Medeiros (2019) and consists of 30 Likert-type items, ranging from 0 (“none”) to 4 (“four or more times a week”) that represent the frequency of occurrence of four bullying behaviors in the last month. The scale is four-dimensional and allows identifying the extent to which an individual has been victimized by physical (11 items; e.g., At my school, lately, I have been a victim of slaps (for example, on the back of the neck, head, back, etc.), verbal (6 items; e.g., I have been a victim of things people say that make me cry), relational (4 items; e.g., I have been a victim of exclusion from groups for no apparent reason (for example, work groups, play groups, etc.), and cyberbullying (9 items; e.g., I have been a victim of creation of false profiles (fakes) about me on social networks). Scores are computed separately for each type of bullying. Higher scores in each subscale that measured the different types of bullying mean that the student was a victim of bullying. In the validation study (Gomes, 2020), the results suggest acceptable evidence of validity and precision [CFI=.98, TLI=.98, RMSEA (90% CI)=.032 (.015-.045)]. Cronbach’s alphas in the present study were: Physical Bullying (α=.79), Verbal Bullying (α=.81), Relational Bullying (α=.67), and Cyberbullying (α=.63).

Bullying Behavior Scale (BBS): This scale also contains 30 Likert-type items, ranging from 0 (“none”) to 4 (“four or more times a week”) and was developed by Medeiros et al. (2015). It allows investigating the extent to which an individual practices bullying behaviors in the same four dimensions of bullying: physical (11 items; e.g., At my school, recently, I have exhibited the following behaviors towards my classmates: I pulled (hair, underwear, clothes, ears), verbal (6 items; e.g., I made a classmate cry because of something I said), relational (5 items; e.g., I have excluded and/or convinced friends to isolate other classmates from groups for no apparent reason (e.g. work, play, etc.) and cyberbullying (9 items; e.g., I have made offensive comments on photos of classmates on the internet). Higher scores on each subscale measuring different types of bullying indicate greater reported bullying behavior towards peers. This instrument was validated solely through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA); no validation studies using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were found. Cronbach’s alphas in the present study were: Physical Bullying (α=.72), Verbal Bullying (α=.71), Relational Bullying (α=.42), and Cyberbullying (α=.69). Therefore, only the dimension related to relational bullying behavior may be considered unsatisfactory in terms of reliability in this study. Consequently, results involving this dimension should be interpreted with greater caution.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE): The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (1979) is a unidimensional measure that assesses global self-esteem. It presents ten statements that measure feelings related to self-esteem and self-acceptance, six of which relate to a positive view of oneself (e.g., I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others) and four refer to a self-deprecating view (e.g., At times I think I am no good at all). The response options are Likert-type, with four points ranging from 1 (“totally disagree”) to 4 (“totally agree”). Items 3, 5, 8, 9 and 10 are inverted for analysis purposes. The total scores of the scale range from 0-30. Scores between 15 and 25 are within normal range; scores below 15 suggest low self-esteem. Confirmatory factor analysis (Sbicigo et al., 2010) supported the bifactor model, showing favorable fit indices (TLI=.954; CFI=.965; RMSEA=.048). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .87.

Global Life Satisfaction Scale (GSLS): The Global Life Satisfaction Scale for Adolescents (Segabinazi et al., 2014) assesses the cognitive dimension of subjective well-being. It consists of 10 items rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much”), evaluating overall life satisfaction in adolescents. An example of a school item is “I like my life”. Higher scores (between 40 e 50) mean that the adolescents are quite satisfied with their lives. The results from CFA showed good fit indices [χ2=7.128; NFI=.989, TLI=.977; CFI=.992; RMSEA=.069 (.019-.126)]. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .90.

Procedure

This is a quantitative, descriptive, relational, and ex post facto study. The study employs a cross-sectional design, with data collected once from students across various age groups. Data collection occurred between June and September 2021, during which all academic activities were conducted remotely.

Initially, the director of the institution was asked to sign the Consent Form, formalizing agreement to conduct the research at their institution. Students over 18 years of age then signed the Informed Consent Form (ICF), while parents or guardians of minors also signed the ICF. Subsequently, the project was presented to students via Google Meet during class time. Students were invited to participate, and links to access the survey questions were provided immediately. For minors, after confirming parental acceptance, the researcher contacted them to inform them of their parents’ formalized acceptance. All participants then received links to access and confirm their consent to participate and answer the questions. The researcher remained available to clarify any questions related to the research.

The project adhered to the guidelines of Resolutions 466/2012 and 510/2016 of the National Health Council and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Southern Bahia under registration number 4.594.739 (CAAE: 40189420.6.0000.8467) on March 16, 2021.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Initially, the descriptive statistics of the variables were verified using the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values. To assess the asymmetry of the distribution of the means, skewness and kurtosis coefficients were used, with acceptable values being those in the range of -2 to +2. The Shapiro-Wilk test was also employed to test the normality of the variables under study. Once we determined that the distributions of the variables under study were non-normal, we squared root them and performed a Pearson correlation test to investigate the relationships among different types of bullying, focusing on victimization and aggressor behaviors.

Furthermore, considering sex differences in self-esteem and life satisfaction, ANCOVAs were employed to examine whether the effects of bullying type on these variables remained unchanged after controlling for sex as a covariate. Sex differences in self-esteem and life satisfaction are well-documented in the literature (Casale, 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Joshanloo & Jovanović, 2020; Kling et al., 1999). Introducing sex as a covariate helps to distinguish between the effects of bullying and any effects that might solely be attributed to sex differences. This methodological choice enhances the study’s rigor and the validity of conclusions drawn regarding the impact of bullying on adolescents’ self-esteem and life satisfaction.

In this study, to compose the group of victims of each type of bullying, we considered those adolescents who reported that they were victims of a certain type of bullying, at least once a week, in the last month. Thus, for example, those adolescents who were victimized by physical bullying at least 4 times during the last month were considered victims of physical bullying. This criterion aligns with previous research that defines frequent bullying as experiencing bullying behaviors on a weekly basis or more often, which is indicative of a sustained and impactful victimization experience (Nansel et al., 2001; Olweus, 1993).

The accepted significance level was .05, although trend effects were also reported. The significance of a result is influenced not just by the p-value but also by the effect size. Therefore, we reported the effect size alongside the p-value because it provides a more comprehensive understanding of the results (Cumming, 2014). According to Greenland et al. (2016), marginally significant results might indicate a genuine effect that warrants further investigation, especially in exploratory research contexts or when previous studies have suggested similar trends. Furthermore, the interpretation of marginally significant results should consider the broader research context. If the findings align with prior studies or theoretical expectations, which is the case here, they can be considered more credible. Replication studies or meta-analyses can help validate these findings over time, providing a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation (Ioannidis, 2005). Finally, it is essential to report marginally significant results transparently, including the exact p-values and confidence intervals for the mean values. This practice promotes openness and allows other researchers to make informed judgments about the validity and reliability of the findings (Nosek et al., 2015). These analyzes were carried out in IBM/SPSS Statistics 25.

Results

Of the total participants, 66 (34%) were victims of cyberbullying, 123 (63.4%) of verbal bullying, 72 (37.1%) of physical bullying, and 83 (42.8%) of relational bullying. On the other hand, 17 (8.8%) were cyberbullying aggressors, 101 (52.1%) verbal bullying aggressors, 36 (18.6%) physical bullying aggressors, and 28 (14.4%) relational bullying aggressors. Regarding bullying typologies, 16 students (8.2%) were only aggressors, 45 (23.2%) were only victims, 94 (48.5%) were victims/aggressors, and 39 (20.1%) had no involvement in bullying behaviors.

Proportion of victims and perpetrators of different types of bullying, according to adolescents’ sex

Regarding the proportions of girls and boys in each of the groups of bullying behaviors, the group of victims of cyberbullying was made up of 45 (37.8%) girls and 21 (28.0%) boys, the group of verbal bullying victims consisted of 77 (64.7%) girls and 46 (61.3%) boys, the group of physical bullying victims included 44 (37.0%) girls and 28 (37.3%) boys, and finally, the group of relational bullying victims comprised 52 (43.7%) girls and 31 (41.3%) boys. With regard to aggressive behavior, 11 (9.2%) girls and 6 (8.0%) boys reported engaging in cyberbullying, 59 (49.6%) girls and 42 (56%) boys engaged in verbal bullying, 17 (14.3%) girls and 19 (25.3%) boys engaged in physical bullying, and 18 (15.1%) girls and 10 (13.3%) boys engaged in relational bullying.

Self-esteem and life satisfaction, according to adolescents’ sex

Additionally, we estimated the average self-esteem and life satisfaction of girls and boys. We found that girls and boys reported low self-esteem (M=1.48, CI=1.37-1.59 and M=1.60, CI=1.46-1.74, respectively), with the midpoint of the scale being 2.5. Furthermore, levels of life satisfaction were high for both girls and boys (M=3.41, CI=3.23-3.60 and M=3.52, CI=3.27-3.76, respectively), with the midpoint of the scale being 3.0. Boys showed slightly higher levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction compared to girls, although this group difference was not statistically significant.

Correlations between the different types of bullying among victims and aggressors

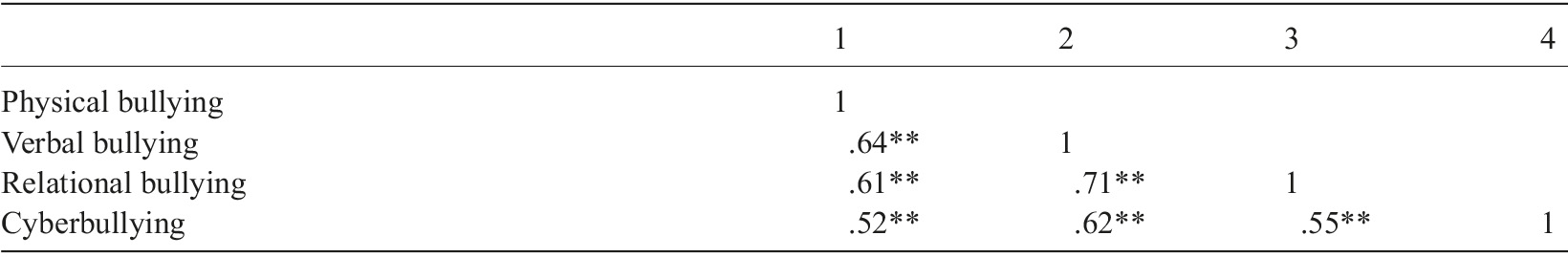

Initially, we investigated how the different types of bullying would relate to each other, considering both, victims and perpetrators. Table 1 presents the Pearson’s correlation coefficients across different types of bullying in relation to victimization.

Table 1 Correlation between all types of bullying among victims

Note. ** Significant difference p≤.001.

As shown in Table 1, all forms of bullying victimization were positively and highly correlated, with moderate magnitudes of correlation. The strongest correlations were observed between verbal and relational bullying, cyberbullying and verbal bullying and between relational and physical bullying. The weakest correlation, on the other hand, was observed between physical and cyberbullying.

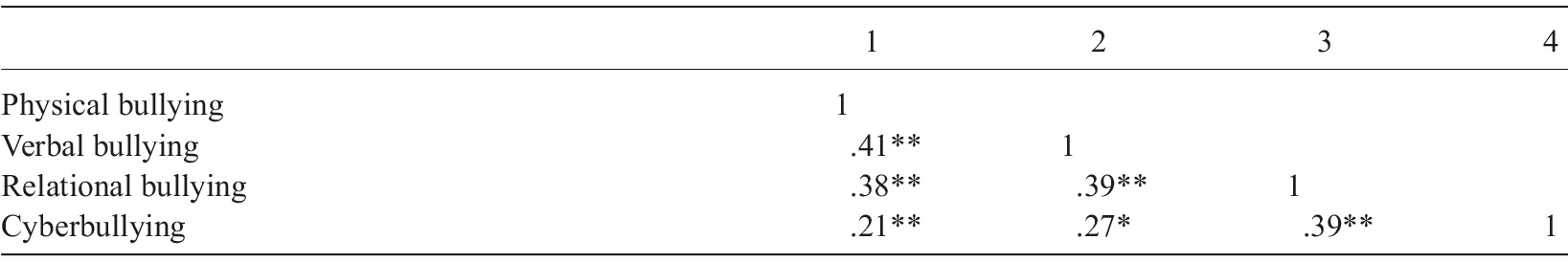

Table 2 displays the Pearson’s correlation coefficients across different types of bullying, focusing on aggressor behavior.

Table 2 Correlation between all types of bullying among perpetrators

Note. ** Significant difference p≤.001.

As shown in Table 2, the correlations between the types of bullying practiced were also significant and positive, though less strong than in the case of victimization. In fact, all of them were considered weak. The strongest correlation was observed between verbal and physical bullying, and between relational and verbal bullying, while the weakest was between physical and cyberbullying.

Self-esteem and life satisfaction among victims of different types of bullying when compared with non-victims, considering adolescents’ sex

To investigate the differences in self-esteem and life satisfaction between victims and non-victims of bullying and bullies and non-bullies, controlling for the effects of the sex variable a series of ANCOVAS were performed. Potential violations of statistical assumptions in ANCOVA were examined, including normality of residuals, homogeneity of variances, and linearity between covariates and dependent variables. Before conducting ANCOVAs, the normality of dependent variables (self-esteem and life satisfaction) and residuals from preliminary analyses was assessed. Visual methods such as histograms and Q-Q plots, along with formal tests like the Shapiro-Wilk test, were utilized. Due to violations of the normality assumption, square root transformations were applied to the dependent variables, which helped stabilize variances and normalize distributions. Homogeneity of variances was confirmed using Levene’s test. Finally, linearity between covariates and dependent variables was confirmed by observing scatterplots, allowing the relationship between each covariate and the dependent variable to be visually inspected.

We found that victimization by relational bullying has a significant effect (F (2,194)=7.07; p=.009; η 2 p=.04) on levels of satisfaction with life, and that victimization by verbal bullying has a tendency effect (F (2,194)=2.83; p=.094; η 2 p=.02) on levels of satisfaction with life, after controlling for the sex covariate. The effect sizes in both cases were small, suggesting that approximately 4% of the variance in life satisfaction can be attributed to relational bullying, and 2% of the variance in self-esteem can be attributed to verbal bullying, after controlling for the covariate. The mean value for life satisfaction was 1.88, 95%CI [1.83-1.94] for non-victims and 1.77, 95% CI [1.70-1.83] for victims. The mean value for self-esteem was 1.88, 95%CI [1.81-1.95] for non-victims and 1.81, 95%CI [1.75-1.86] for victims.

With regard to self-esteem, the analysis showed a significant effect (F (2,194)=9.28; p=.003; η 2 p=.05) of relational bullying on self-esteem levels, even after controlling for the effect of sex. The effect size found was also small, suggesting that approximately 6% of the variance in self-esteem can be attributed to relational bullying. The mean value for self-esteem was 1.26 for non-victims, 95%CI [1.20-1.31] and 1.14 for victims, 95%CI [1.08-1.19]. Thus, participants who reported being victims of relational bullying had lower self-esteem scores compared to non-victims, after adjusting for age. A tendency of an effect of verbal bullying (F (2,194)=3.64, p=.058, η 2 =.02, η 2 p=.02) on this variable was also observed, with a small effect size, suggesting that approximately 2% of the variance in self-esteem can be attributed to verbal bullying. The mean value for self-esteem was 1.25 for non-victims, 95%CI [1.19-1.32] and 1.18 for victims, 95%CI [1.13-1.22]. Thus, participants who reported being victims of verbal bullying also had lower self-esteem scores compared to non-victims, after adjusting for age.

Self-esteem and life satisfaction among perpetrators of different types of bullying when com- pared with non-aggressors, considering adolescents’ sex

With the exception of aggression through physical bullying, which was greater among boys, all other forms of aggression were practiced more by girls. To analyze the effects of types of aggression on levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction, controlling for the sex covariate, we also performed some ANCOVAs. We found a significant effect of relational bullying on life satisfaction (F (2,194)=4.48; p=.036; η 2 p=.02). This means that a small effect size was found, suggesting that approximately 2% of the variance in life satisfaction can be attributed to relational bullying. The mean value for life satisfaction among non-aggressors was 1.85, 95%IC [1.80-1.90] and among aggressors was 1.72, 95%IC [1.61-1.83]. Thus, participants who reported being perpetrators of relational bullying had lower life satisfaction scores compared to non-bullies, after adjusting for age.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate whether Brazilian students from a Federal Institution who have been victims of bullying and students who have been bullies differ in terms of self-esteem and life satisfaction from those who have never been victims or bullies, while controlling for the effects of the sex covariate.

We found a high prevalence of victimization, especially in cases of verbal and relational bullying, despite the data collection taking place during the second year of COVID-19, when face-to-face activities were suspended at the educational institution. The prevalence of aggression through verbal bullying was also highest. We anticipated that social distancing measures would influence various forms of bullying, including physical, relational, and verbal. In this regard, Vaillancourt et al. (2021, 2023) and Kennedy and Dendy (2024) highlighted shifts in bullying dynamics during the pandemic. Vaillancourt et al. (2021) observed a decrease in traditional face-to-face bullying due to school closures and increased remote learning, but noted a rise in cyberbullying incidents as students spent more time online. According to Vaillancourt et al. (2023), a decrease in traditional bullying victimization and perpetration during the pandemic, especially with the shift to online learning in some countries, has been observed. However, countries with fewer social restrictions reported increased bullying rates. Similarly, in a recent meta-analysis, Kennedy and Dendy (2024) identified significant changes in bullying dynamics attributed to the pandemic, particularly because of school closures and remote learning. These changes altered patterns of both traditional and cyberbullying, with students increasingly engaging in harmful behaviors through digital platforms like social media, messaging apps, and online forums.

However, in the current study, it appears that participants reported their behaviors within an extracurricular context. Therefore, the context of COVID-19 does not seem to have a significant impact on the descriptive results. In fact, another national study also found that these two types of bullying are the most common among Brazilian teenagers aged 13 to 17 years old (Veloso et al., 2020).

In the correlational analyses regarding victimization, significant and substantial correlations were observed among the four types of bullying, suggesting that adolescents who experience one type of bullying are also at a higher risk of experiencing another type, as found by Zhang et al. (2014). This indicates that victims often endure multiple forms of bullying, intensifying the issue. A similar pattern of correlations was observed by Johansson and Englund (2021), who also noted high correlations between physical, verbal, and relational bullying.

Regarding aggressive behavior, we found significant relationships between all four types of aggressive behaviors. Notably, all the were positive, but weak. According to Zhang et al. (2014), this suggests that these types of bullying are unlikely to be different manifestations of the same underlying phenomenon, but more likely are different phenomena. Nevertheless, the fact that we found significant correlations between all types of aggression, makes the bullying behavior more overt and violent and more challenging to combat.

When we compared groups of victims of the four types of bullying with those who were not victims in relation to self-esteem and life satisfaction, we found that victims of verbal and relational bullying exhibited lower levels of life satisfaction than non-victims, and these effects remained significant even after controlling for the effects of sex. Furthermore, victims of relational bullying also showed lower levels of self-esteem than those who had never been victimized. A difference that was very close to being statistically significant was also observed regarding the self-esteem of victims of verbal bullying. In other words, these victims had lower average self-esteem scores than non-victims. In both cases, these effects also remained significant after controlling for the participants’ sex. Thus, the results partially confirm the first hypothesis that victims of all forms of bullying would have lower levels of self-esteem than non-victims, even after controlling for the effect of sex, and the second hypothesis that victims of bullying would have lower life satisfaction scores than non-victims, even after controlling for the effect of sex.

The significant or nearly significant findings only for relational and verbal bullying can be explained if we take into account that the sample consisted of very young people (aged 15 to 21). These two types of bullying are more common during this period of life, particularly in adolescence, when young people establish more peer relationships and develop more subtle forms of bullying, such as relational bullying (Berger, 2007). In fact, these two forms of victimization were the most common in the current study and are therefore the ones that can most affect students’ self-esteem and life satisfaction.

These results corroborate previous studies indicating low life satisfaction among victims of bullying (Callaghan et al., 2015; Weng et al., 2017). Similarly, according to several authors, bullying behavior has an impact on the self-esteem of victims (Bandeira, 2009; Cantini, 2004; Cénat et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2014; van Geel et al., 2018).

Furthermore, the results indicate that students who reported engaging in verbal, physical, and cyberbullying do not differ significantly in terms of levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction from those who have never engaged in bullying. However, it was observed that students who have engaged in relational bullying have lower levels of life satisfaction than their peers who have never engaged in bullying, after controlling for the participants’ sex. In this case, the third hypothesis - that bullies would have lower levels of life satisfaction - was also partially confirmed, as significant results were found only for aggressors of relational bullying.

The non-significant results are noteworthy because they contradict literature suggesting that bullies may have low self-esteem (Callaghan et al., 2015; Estévez et al., 2018; Flaspohler et al., 2009; Navarro et al., 2013; Serra-Negra et al., 2015; Weng et al., 2017). However, the studies generally do not differentiate between the four types of bullying in their results; they typically include only a general category of bullies. Therefore, it is possible to infer that considering the four types of bullying separately could lead to different results.

In any case, some studies corroborate our findings. For instance, Mota et al. (2024) found that self-esteem negatively predicted bullying behaviors among peers - both victimization and aggression - specifically regarding relational bullying (social exclusion). Furthermore, the significant results for relational bullying can be explained by considering that high self-esteem has the potential to promote the expansion of one’s social network (Mota & Matos, 2009), which, in turn, can create opportunities for developing more adjusted social relations (Rocha & Matos, 2012) and subsequently enhance self-esteem.

The results regarding the low life satisfaction of those who engage in relational bullying have been observed in other studies (Flaspohler et al., 2009; Navarro et al., 2013). For instance, Flaspohler et al. (2009) found that students who engaged in physical, verbal, and relational bullying reported lower levels of general life satisfaction compared to non-involved students. Navarro et al. (2013) also found that social bullies reported lower levels of satisfaction in family, friendship, school, and self as compared to non-involved students.

One possible explanation for the findings indicating that physical, verbal, and cyberbullying aggressors do not differ significantly from non-bullies in terms of overall life satisfaction is that this variable may have functioned as a protective factor by buffering the frequency of students’ involvement as bullies. Hence, this may have contributed to the lack of significant relationships between students’ levels of life satisfaction and their involvement in these three types of bullying, as Parrill (2015) explains in his study. It is worth noting that in the current study, participants reported high levels of life satisfaction, which may have facilitated this buffering effect.

We did not formulate specific initial hypotheses regarding the self-esteem of bullies, and we did not find significant differences in self-esteem when comparing bullies and non-bullies. Self-esteem is a multifaceted construct that may not be directly linked to specific bullying behaviors. Therefore, other factors such as family dynamics, peer relationships, and individual personality traits might also play a significant role in self-esteem. Additionally, in this study most bullies in the sample engaged primarily in verbal bullying, which might obscure differences in self-esteem between bullies and non-bullies. Furthermore, the overall self-esteem scores of participants were relatively low, and this low variability can limit the ability to find significant differences. Finally, bullying might be a phase or transitory behavior for some individuals. If bullies are not consistent in their behavior, it may not significantly impact their self-esteem compared to those who do not engage in bullying at all.

The current study is one of the first to assess global life satisfaction and self-esteem among adolescent students in a Brazilian sample, comparing victims and non-victims, as well as aggressors and non-aggressors of four different types of bullying, with regard to these two psychological variables, while controlling for the covariate of sex.

This study advances understanding of the phenomenon of bullying compared to previous studies by measuring and analyzing two psychological variables that are important correlates of bullying behaviors. Additionally, we utilized instruments that have been preliminarily validated for the Brazilian context. Finally, our study included a relatively large sample of 194 students, teenagers, and young adults.

As indicated in the literature review, self-esteem is considered an indicator of mental health in adolescence. Moreover, high life satisfaction among adolescents is associated with positive developmental outcomes, serving as protection against risk factors during this stage of life. Therefore, understanding how bullying impacts these psychological variables contributes to advancing scientific knowledge in this area, which can inform the planning of educational and therapeutic interventions for both victims and aggressors.

Like all research, the current study has some limitations. Firstly, convenience sampling was employed from a single institution, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other secondary education institutions in Bahia state or Brazil as a whole. Additionally, data collection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, characterized by the complete absence of face-to-face interactions among participants. Consequently, the prevalence of certain types of bullying, such as physical, relational, and verbal bullying, might be even higher than reported due to social distancing measures and remote classes. Thus, it is essential for future studies to investigate these behaviors post-pandemic to obtain a clearer picture.

Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study, which precludes tracking the evolution of the phenomenon and conducting a more in-depth exploration of predictors of bullying behaviors. Therefore, future research should adopt longitudinal methodologies to examine whether low self-esteem and life satisfaction can explain changes in bullying behavior over time.

We also must consider that some participants simultaneously experienced or perpetrated various types of bullying, and some were both bullies and victims. However, data analyses were conducted separately for bullies and victims, with each type of bullying considered independently. This approach has limitations, such as not accounting for the complexities of bully-victim dynamics and the overlapping nature of bullying roles. Future research should explore these overlapping roles more comprehensively and consider the interactions between different types of bullying to better understand their combined effects on psychological outcomes. Finally, despite the advancements facilitated by quantitative research, future studies can also explore a qualitative-quantitative approach. This approach aims to provide deeper insights into how psychological characteristics, such as self-esteem and life satisfaction, influence the outcomes of bullying behaviors among victims and aggressors across all types.