Introduction

Respecting others is one of the most powerful ingredients for creating and nurturing fair individuals and, consequently, just societies (Ignatieff, 2017; Lawrence-Lightfoot, 2000; Murdoch, 1970). Feelings, expressions, and behaviours of respect entail an appreciation of the other person, acknowledging their individuality and feelings (Kalkavage, 2001). Consequently, respect plays an important role as a moral emotion for socioemotional development and in shaping our moral orientations (Malti et al., 2020; Turiel & Killen, 2010).

Morality and respect are intertwined in both philosophical and psychological literature. Kant (2006) emphasized respect as a subject of study, describing it as an emotion that fosters morality and establishing three domains: (1) respect for the moral law; (2) respect for a person’s exceptional character; and (3) respect for a person as such - as a human being. Subsequently, these latter two definitions requested a broader distinction between respecting someone for their merits and considering their social position (Drummond, 2006). In psychological literature, Piaget’s theory serves as an important framework for understanding moral development. Piaget stated that children develop from a heteronomous morality, which relies on the authority of others, to a more autonomous morality. This transition occurs through children’s reciprocal interactions with adults and peers, particularly in contexts involving social problems, conflicts, and challenges, leading them to attain a heteronomous morality (Piaget, 1932). During childhood, peer relationships provide the context to establish relations marked by reciprocity that contribute to the transition toward more autonomous thinking. This transition involves the cultivation of mutual respect and concerns regarding fairness, justice, and cooperation (Turiel, 2014). From an early age, children show moral concerns and display moral issues related to relationships and family dynamics (Nucci, 2014; Smetana et al., 2014), harm (e.g., Tisak et al., 2006), justice and rights (Helwig et al., 2014). The foundations for moral and social reasoning, including the analysis of existing social conditions and even opposition to those conditions, are also present in childhood (Turiel, 2014).

Development of respect

Respecting others implies caring, paying attention, and being conscious of others (i.e., an apprehensive component), but also implies cognitive factors directed at appreciating others deemed worthy of, and reasonings for that appreciation (i.e., a responsive component) (Malti, 2020). According to Buss (1999) respect is primarily an emotional response (i.e., affective component) that might include cognitive judgments regarding how worthy someone is (i.e., cognitive component) of being treated in a certain way (i.e., motivational component). Furthermore, expressions or behaviors of respect may be explicit, such as intentionally showing kindness to others (e.g., by sharing fairly with everyone and helping another person), or implicit, involving attitudes toward others (e.g., in certain gestures and stances regarding others) (Dillon, 2007; Malti et al., 2020).

In a recent study, Malti et al. (2020) propose that the conceptualization of respect should be considered in a broader and intrapersonal way. This involves examining not only how children define and describe respect (i.e., respect conception) but also how they express respect toward others (i.e., expressions of respect) and perceive being respected by others (i.e., respect from others), which naturally occur within interpersonal relationships (Malti et al., 2020). To explore children’s conceptualization of respect, Malti and colleagues proposed six main categories: fairness, prosocial, social convention, authority, merit, and personal freedom. The results of the study revealed that children start to conceptualize respect by evoking mainly themes of pro-sociality (i.e., other‐oriented behaviors such as helping, giving, sharing, and displaying kind actions or emotions). Subsequently, they develop an understanding of respect based on fairness, which encompasses concepts of justice, equality, and reciprocity. Furthermore, children perceive behaviors reflecting fairness or kindness as worthier of respect compared to those based on merit or performance (Malti et al., 2020).

Relations between respect and sympathy

In the developmental socioemotional literature, respect and sympathy are described as other- oriented emotions, although they differ in their emotional valence (e.g., Malti et al., 2018, 2020). Sympathy has a negative valence and emphasizes the aversive aspects of a situation (e.g., seeing someone getting hurt or bullied). Contrarily, respect has positive emotional valence, evoking positive feelings that resonate with an individual’s ethical concerns (e.g. when someone shares with or helps those in need) (Malti et al., 2018; Malti & Latzko, 2017).

Sympathy can be defined as a kind or compassionate gesture that generates a sense of protection and acceptance, serving as an enabler in communication with others, while tending not to give plateau to feelings of fear, doubt, and insecurity (Piero, 2006). It can be characterized by feelings of concern, sadness, or pity for another and implies awareness and recognition of another’s emotional or situational state (Eisenberg, 1986; Eisenberg et al., 1996), along with a desire to relieve the other person’s negative emotions (Eisenberg et al., 1991). Sympathy is often misread with empathy; however, sympathy involves more than sharing the emotional state of the other, always resulting in a concern for the other person (Colasante & Malti, 2017; Eisenberg, 2000, 2018). Sympathy tends to direct the child’s attention to the consequences of their actions and the well-being of others and may assume an empathic experience of sharing the other person’s feelings. Additionally, sympathy is empirically related to more altruistic forms of prosocial behaviours (Costa Martins et al., 2022; Eisenberg & Miller, 1987; Malti et al., 2009).

Previous studies have demonstrated that respect is associated with kindness, prosocial behavior and positive social outcomes (e.g., Cohen et al., 2006; Hsueh et al., 2005; Huo & Binning, 2008; Langdon & Preble, 2008; Mayseless & Scharf, 2011). Empathy and sympathy can be considered the foundation for more complex other-oriented emotions, such as feelings of respect for others. Valuing someone as truly good motivates us to act kindly, thereby fulfilling our expectations, intentions, and desires (Drummond, 2022). Acknowledging the other as a different entity creates a moral space in which respect can develop (Drummond 2006).

Malti and colleagues (2020), in a study involving an ethically mixed sample of children and adolescents (5 and 15 years old), found that respect, specifically when based on fairness (regarding social circumstances of sharing fairly and social inclusion) was positively related to sympathy. However, sympathy was not a significant predictor of respect conceptualizations. Other studies have also founded a positive association between child’s sympathy and respect for moral others (Zuffianò et al., 2015), as well as between respect and prosocial behaviour (Kuryluk et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2020). In contrast, some studies have revealed negative associations between respect and aggression (Peplak & Malti, 2017), specifically overt aggression and relational aggression (Kuryluk et al., 2011).

Aim and hypotheses of the study

Even though respect is a universal construct present across history and cultures, there is still evidence of some cultural variability in children’s evaluation and understanding of the concept. For instance, differences were found between American and Chinese samples of children regarding the motives behind respect (with the first one focusing more on obedience to adults, and the second one more on admiration) however both samples suggested reciprocity as a motive for respect (Hsueh at al., 2005). Further research is needed to provide a deeper understanding of the impact that implicit cultural norms have on children’s developing notion of respect. Therefore, replications of previous studies and findings using samples from different cultures are important.

The aim of the present study is to replicate Malti’s study and first evaluate the notions of respect expressed by Portuguese children, and secondly, examine its relationship with sympathy. Specifically, we aim to examine (1) possible age-related differences in the associations between respect and sympathy, (2) if girls are perceived as more sympathetic and more ethical in their respect conceptualizations, (3) if children who conceptualize respect using ethical themes (justice, pro-sociality, and personal freedom) are more sympathetic compared to those who don’t use those themes.

Method

Participants

The present study included 53 children, 28 females (52.8%) and 25 males (47.2%), aged between 5 and 8 years. Children were mostly Portuguese (93%), 60.4% were firstborns and 75.5% had at least one sibling. Parents, mostly mothers (85%) also participated. The maternal average age ranged from 29 to 49 years (M=38.25; SD=5.01); and the paternal average age ranged from 30 to 64 years (M=41.20; SD=7.50). Most parents lived together, 61.5% were married; 19.2% were cohabiting and 13.5% of the families were separated or divorced, 5.8% were in another situation (ex. widow). Parents worked mostly full-time (82.7% and 92.5%, mothers and fathers respectively), 11.5% of the mothers and 5.7% of the fathers worked part-time jobs, and 5.8% of the mothers and 1.9% of the fathers were unemployed. Most mothers and fathers had higher education with at least bachelor’s degree (72.5% and 69.2% respectively).

The inclusion criteria were families that were fluent in Portuguese and had a child aged between 5 to 8 years old. Children who revealed significant difficulty or a lack of verbal understanding during the interviews were not included in the analysis (however considering this criterion and considering language barriers with bilingual children or with different Portuguese accents, no children was excluded).

Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. The sociodemographic questionnaire was designed to describe key characteristics of the sample, including child’s sex, age, school year, number of siblings, whether they were the firstborn, and the number of hours spent in school each week. Additionally, it gathered information on the mothers’ and fathers’ levels of education and their professional situations.

Respect interview (Malti, 2020; Malti & Ongley, 2014). This interview aims to characterize the behaviors children consider to be respectful. The script used in the present study was developed by Malti et al. (2020) and translated into Portuguese by the research team. The first part of the interview is dedicated to the children’s conceptions of respect, using three open-ended questions. The first question evaluates the general understanding of respect (i.e., the concept of respect: “What does it mean to feel respect for someone?”). The following questions address how children show respect to others (i.e., expression of respect: “Tell me about a time when you respected someone”). The final question evaluates how children perceived being respected by others (i.e., respect from others: “Tell me about a time/situation when someone respected you.”).

The responses were classified using the coding system for conceptions of respect developed by Malti et al. (2020), composed by seven categories. A maximum of three categories were coded for each child. These seven categories included: (1) fairness (i.e., responses including the Golden Rule, impartial treatment, and respect for the rights of others); (2) pro-sociality (i.e., other-oriented themes such as engaging in sharing or empathy); (3) social convention (i.e., responses based on following socially defined rules and regulations, namely the use of good manners); (4) merit (i.e., themes focused on achievement or success); (5) authority (i.e., responses related to obedience to avoid punishment and regarding orders from authority figures - parents, teachers or others); and (6) personal freedom (i.e., themes of autonomy and management/agency, i.e., themes related to preserving choice and personal space). Additionally, the categories “other answers” and “rudimentary / not elaborated answers” were included. Three researchers independently coded a portion of the data (25% of the data) and inter-coder agreement was obtained using Cohen’s κ was 1 (100%).

The final part of the interview evaluates children’s concept of respect as well as the reasons associated with feelings of respect in three social circumstances (Malti, 2020; Malti & Ongley, 2014). These narratives present peers involved in hypothetical behaviours worthy of respect, specifically stories involving themes of “social inclusion”, “fair sharing” (i.e., sharing resources equally), and “good school performance”. The final context/story regarding school performance allowed to assess differences in children’s ethical and unethical evaluations of respect and served as a comparison condition for the other scenarios.

After listening to each story, participants were firstly asked to report how much respect they felt for the protagonist, using a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 “no respect”, to 4 “a lot of respect”). Secondly, children were asked to justify the amount of respect they felt for the protagonist. Regarding 5-year-old and 6-year-old participants, a corresponding visual scale depicting animals of increasing size (i.e., mouse, dog, horse, and elephant) was presented to ensure their understanding. Finally, regarding each story, participant’s reasoning behind their previously evaluated respect were coded with the 7 categories used to analysed respect conceptions.

Sympathy Scale (children report and parents report), original from Eisenberg et al., 1996). The sympathy scale for children consists of six statements (e.g., “I often feel sorry for other children who are sad or in trouble”). After each statement, children were asked whether the sentence described them (or not) and, if so, how strongly. Responses were rated on a scale of 1 to 3, with “This is not like me” assigned a value of 1, “This is sort of like me” assigned a value of 2, and “This is really like me” assigned a value of 3. The Cronbach’s α of the original scale was .80, indicating good internal consistency. However, in the present sample, a Cronbach’s α of only .41 was obtained. The parent version of the sympathy scale includes 5 of the 6 items from the children’s version, using a Likert scale format ranging from 1 to 6 (1 being “it’s not at all like my child/my child” and 6 representing “it’s really like my child”). In the present sample, this scale revealed a Cronbach’s α of .76. Due to the different internal consistency values obtained by the child version, only the parents’ version of the sympathy scale was used in our analysis.

Procedures

This study was conducted following the ethical standards outlined by the American Psychological Association (APA) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of ISPA. Parents of potential participants were contacted via social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) by the researchers, and by the official accounts of the research team. After filling out the sociodemographic questionnaire and the sympathy scale on the Qualtrics platform, parents who provided their email addresses were contacted to schedule respect interviews with their children. Since this research occurred during the pandemic (2021), interviews were mostly performed online (via the platform Zoom) after obtaining children’s assent. Despite being conducted via Zoom, both parts of the respect interviews (the open-ended questions and semi-structured questions), took place in a calm environment free of interruptions. The online collection enabled a sample with Portuguese families from various parts of Portugal, and even with some families living outside the country (e.g., Brazil, London, and Spain, n=4).

Results

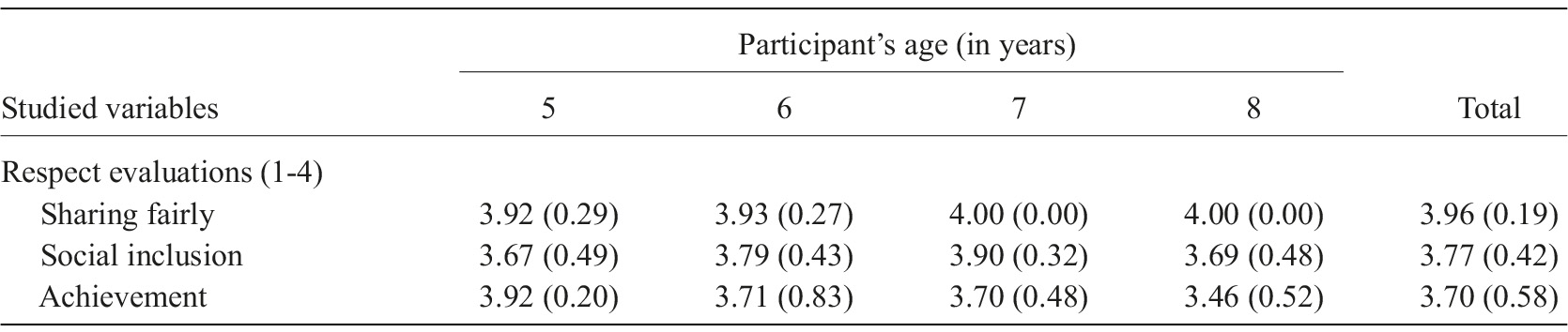

Most children used one or two themes to describe their concept of respect (see Table 1). When specifically answering to each domain of respect (i.e., Respect Concept, Expression of Respect, and Respect from Others), most children employed at least one Ethical theme (i.e., Fairness, Prosocial or Personal Freedom). Specifically, 34.0% used it in all domains, 37.7% in two domains, 11.3% in one domain, and 17.0% did not use it in any domain. Regarding children’s respect evaluation and associated reasoning in the three social contexts (i.e., Social Inclusion, Sharing Fairly, and Academic Achievement) Ethical themes were the most used except for the academic- related goals (see Table 1). Children predominantly exclusively used Ethical themes when addressing Respect from Others, Social Inclusion and Sharing Fairly (see Table 1).

Table 1 Percentage of children by number and type of themes used to describe respect, organized by domains

Note. Mixed: used both ethic and non-ethic themes.

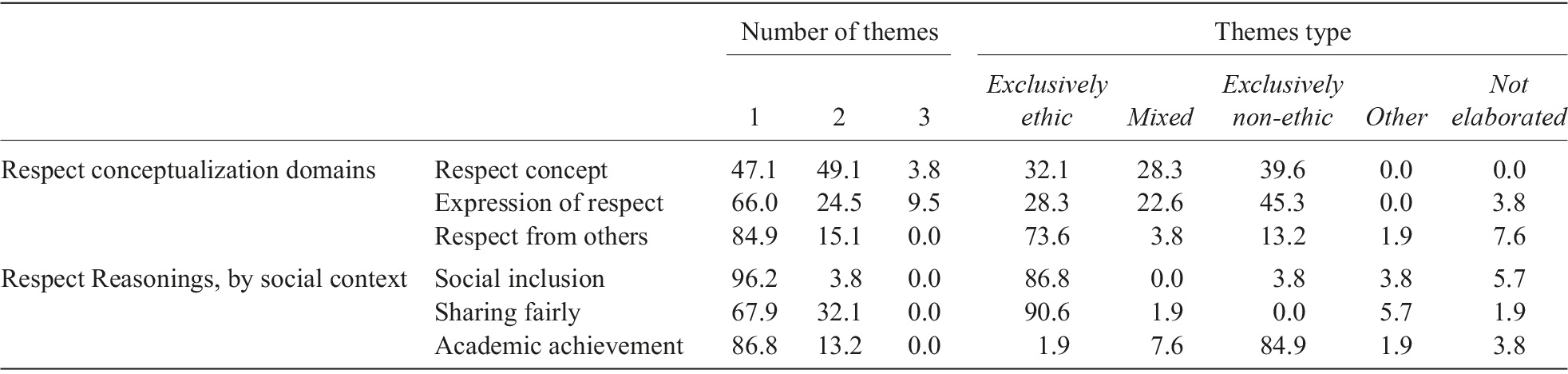

The most frequently mentioned themes for Respect Concept were Social Convention (56.6%), Prosocial (39.6%), Fairness (30.2%), and Authority (26.4%). For Expressing Respect, the most common themes were Prosocial (47.2%), Authority (39.6%), and Social Convention (37.7%). Regarding Respect from Others the most mentioned categories were Prosocial (54.7%), Personal Freedom (28.3%), and Social Convention (13.2%) (see Figure 1). Girls used the Social Convention theme more frequently in the Expression of Respect domain compared to boys [χ 2 (1)=6.33, p<.01; girls=53.6% and boys=20%]. Firstborns mentioned Fairness more often than not-firstborns when describing the Respect Concept [χ 2 (1)=4.17, p<.05; 40.6 % of the firstborns and 14.3% of the not-firstborns]. There was an association between child age and the use of Prosocial themes as an Expression of Respect, with older children using prosocial themes more frequently (r pb=.29, 95% BC a CI [.02, .52], p<.05). No other significant differences or associations were found.

Note. Categories are non-exclusive and can be cumulative

Figure 1. Percentages of answers given in each category within the three domains of respect (concept, expression and respect from others)

Concerning children’s evaluations of respect for each story context, Figure 2 displays the percentage by theme. In the Social Inclusion story, the majority of children mentioned Prosocial (81.1%). For the Share Fairly story, Fairness was the most mentioned theme (75.5%), followed by Prosocial (47.2%). Finally, in the Academic Achievement story, the Merit theme was mentioned by 88.7% of the children.

Note. Categories are non-exclusive and can be cumulative

Figure 2. Percentages of children’s evaluations of respect by story context

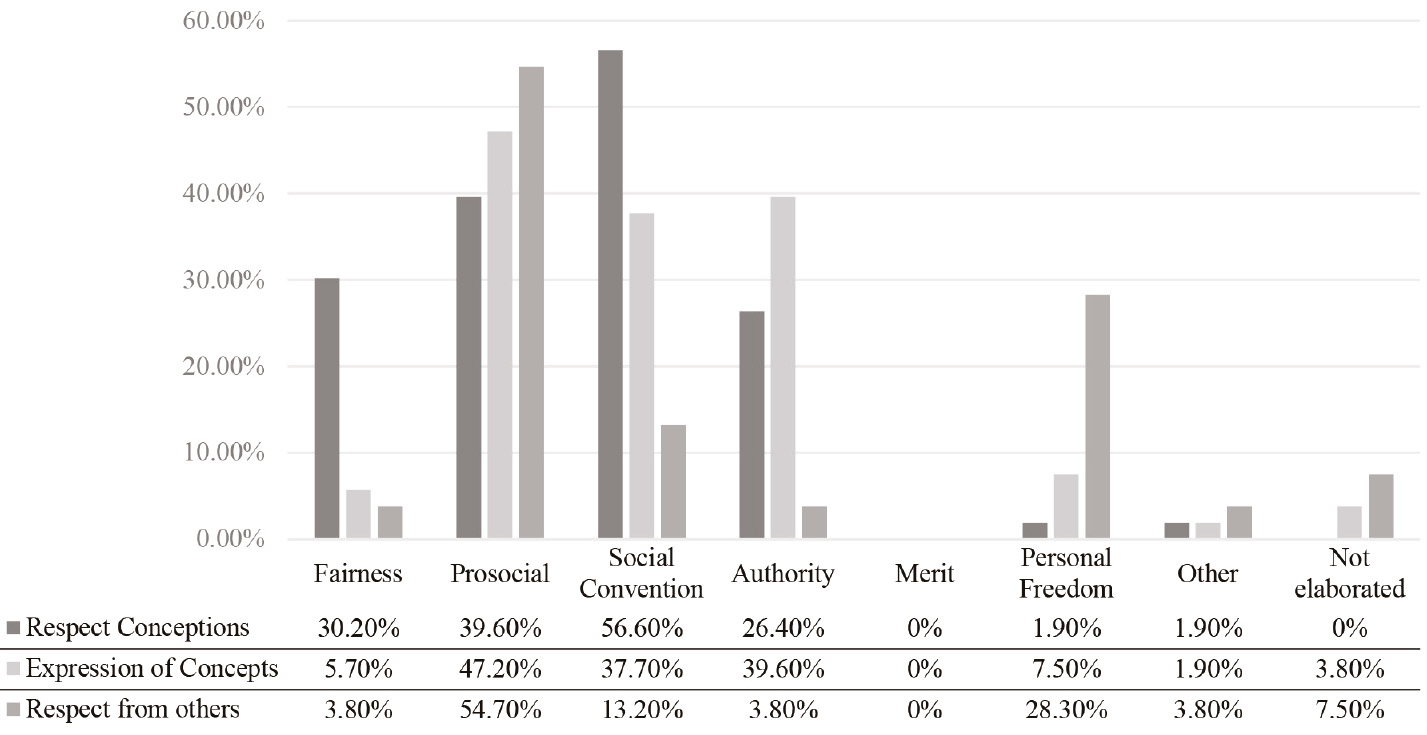

The present sample presented high levels of evaluations of respect (M sharing fairly=3.96, SD=0.19; M social inclusion=3.77, SD=0.42; M academic achievement=3.70, SD=0.58). However, significant differences were observed between sharing fairly and social inclusion [t(53)=3.12, p<.001] and between sharing fairly and academic achievement [t(53)=3.08, p<.01]. Additionally, a significant correlation between social inclusion and academic achievement was found (r=.43, p>.001). When looking into significant differences regarding respect evaluations, boys evaluated academic achievements as worthier of respect than girls [t(-2.345)=39.69, p<.05, M girls=3.54, SD=0.69; M boys=3.88; SD=0.33]. Furthermore, older children (≥7 years old) revealed lower respect evaluations by one’s achievement than younger children [t(49.322)=-2.91, p<.01, M younger=3.94, SD=0.24 M older=3.58, SD=0,65]. For further description of age differences, Table 2 presents the children’s respect evaluations by age group.

Child sympathy

Children were generally described as sympathetic by their parents (M=4.81, SD=0.94), with parents describing girls as more sympathetic compared to boys [t(51)=2.13, p<.05; M=5.06, SD=0.87 for girls and M=4.53, SD=0.96 for boys]. Firstborns were described as less sympathetic compared with non-firstborns [t(51)=-1.70, p<.05; M=4.63, SD=1.02 for firstborns and M=5.08, SD=0.77 for non-firstborns]. Children with siblings were described as more sympathetic [t(49)=3.55, p<.001; M=5.06, SD=0.82 with siblings and M=4.08, SD=0.76 no siblings]. No other differences or correlations were found.

Respect and sympathy

Children who answered to examples of Expressions of Respect with an Authority themed response were reported by their parents to be less sympathetic [t(51)=-1.86, p<.05; M sympathy=4.52, SD=0.90 for authority themed responses and M sympathy=5.00, SD=0.94 for non-authority responses]. No other difference was found.

Several logistics regressions were performed with child age, sex, siblings, and phratry, as well as sympathy as independent variables and respect conception within each domain as the dependent variable. For the conception of respect, there was a main effect of phratry on fairness (Wald χ 2 =4.18, p<.05; b=-1.71, SE=.84) and sympathy on prosocial (Wald χ 2 =3.85, p<.05; b=.90, SE=.46). For Expressions of respect, there was a main effect of child’s age on fairness (Wald χ 2 =3.77, p<.05; b=1.57, SE=.81) and on prosocial (Wald χ 2 =4.37, p<.05; b=.58, SE=.28); sex on social convention (Wald χ 2 =5.71, p<.05; b=-1.86, SE=.78). No other significant result was found (see Table 3).

Discussion

Our results showed high levels of children’s sympathy, a significant use of ethical themes, especially, when addressing respect from others); and behaviors of social inclusion and of sharing fairly were deemed most worthy of respect. As expected, most children employed ethical themes (i.e., fairness, prosocial or personal freedom) when addressing respect (see also, Malti et al., 2020). The incorporation of ethical themes is most evident in the motivations to respect others, but also evident in the reasons provided to be respected, and the conceptualizations of what respect entails. Our results, replicate findings presented in previous studies (e.g., Malti et al., 2020, that used a Canadian sample).

Children were expected to distinguish between respecting others’ achievements and respecting their expressions of kind behaviors (i.e., social inclusion or sharing fairly) (Malti et al., 2020). Most children employed ethical themes when addressing kind behaviors but did not use them when addressing academic achievement scenarios. In our results, children considered all these types of behaviors highly respectful, with sharing equally being the most highly regarded. In this scenario (i.e., sharing equally), the fairness theme was the most frequently used. In the social inclusion scenario, the prosocial theme was predominant, while in the academic achievement scenario, the merit theme was most mentioned.

Older children revealed a more ethical conceptualization across all three domains of respect (e.g., prosocial), but not when the domains were tested separately. Considering sex, our findings confirmed the hypothesis that girls are perceived as more sympathetic than boys (Kienbaum, 2014), and expected sex differences were observed in respect evaluations, with boys giving higher evaluations for academic achievements (Malti et al., 2020). However, contrary to expectations, girls didn’t reveal higher ethical levels in their definition of respect. These results challenge social norms and perceptions concerning sex, suggesting that both boys and girls possess the ability to articulate and report socioemotionally and morally developed responses, rather than it being predominantly attributed to girls.

Our findings suggest that siblings play an important role regarding behaviors of sharing fairly. Older children tend to be more capable of identifying examples marked by fairness and pro-sociality. Furthermore, we observed a sex effect on the use of social convention with girls employing this theme more frequently when conceptualizing respect. This finding may be attributed to perceived gender roles, where girls are often perceived as more attentive to and conscious of social conventions.

Interestingly, we did not find an association between the ethical themes used by children to conceptualize respect and higher levels of sympathy. However, authority themes used when describing expressions of respect revealed a negative effect on sympathy levels. This result was expected, as authority is a non-ethical theme, which may indicate a less sympathetic attitude.

In conclusion, our findings align with previous literature on respect (Drummond, 2022; Kuryluk et al., 2011; Langdon & Preble, 2008; Lim et al., 2020). However, the observed associations were often not strong enough, which may be due to the complexity involved in conceptualizing both respect and sympathy and essentially to the novelty of this subject and of the instruments used, especially for research purposes.

It’s also important to acknowledge several limitations of our study. Firstly, the small sample size may have limited the variability of the data and the possibility of finding the remaining expected effects between variables. Additionally, the data collection procedure, conducted online during the pandemic, may have influenced children’s responses, potentially emphasizing higher feeling of sympathy. Furthermore, limitations associated with the Sympathy Scale, including its low internal consistency necessitating the use of only the parent’s version, as well as the potential for socially desirable responses from parents and the scale’s limited number of items, should be considered. For future research, it’s essential to address these limitations. This could involve utilizing additional sources of data, such as children’s self-reports and teachers’ reports, to complement parental reports. Exploring different contexts, such as institutionalized children or those from varying social statuses, as well as diverse cultural backgrounds, could provide valuable insights and allow for more comprehensive comparisons.

Research on the development of moral emotions, such as respect and sympathy, during childhood remains relatively limited. There is still a lack of validated scientific measures to assess respect and sympathy, as well as a scarcity of studies conducted across diverse cultural contexts. The present research contributes to knowledge in this field, by replicating the study in a different culture setting and age range.