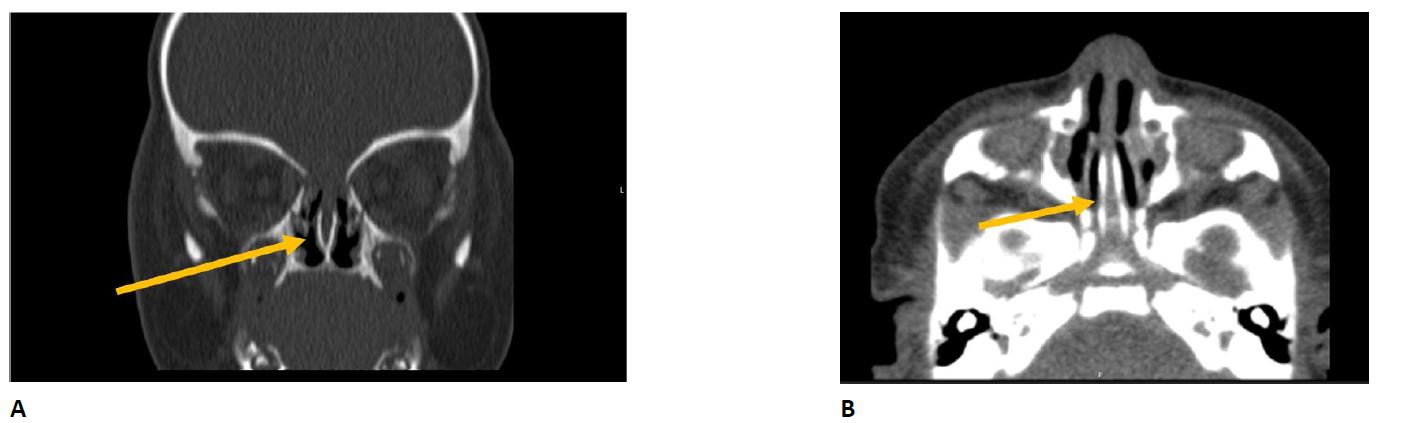

The authors report the case of a full-term male newborn born by eutocic delivery with no need for support in the transition to extrauterine life. At two hours of life, he presented with noisy breathing and respiratory distress and was admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Physical examination revealed normal pulse oximetry, global chest retractions, significant nasal obstruction, and decreased breath sounds. Laboratory data revealed normal blood count and negative inflammatory parameters. Chest radiography was unremarkable. Due to respiratory acidosis confirmed by arterial blood gas analysis, non-invasive ventilation (NIV) was started, with significant improvement in respiratory distress. After 30 hours of NIV with a positive response, supplemental oxygen therapy via nasal cannula with a maximum fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 24% was initiated and maintained until the third day of life. Despite spontaneous ventilation and no further need for supplemental oxygen therapy since the third day of life, nasal obstruction persisted. Therefore, it was decided to initiate treatment with nasal topic phenylephrine, which resulted in transient clinical improvement. Endoscopic evaluation by the otolaryngologist on day 4 of life revealed bilateral bulging of Cottle’s areas IV and V of the nasal septum, resulting in nasal cavity stenosis. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the nose and paranasal sinuses revealed a vomer bone prominence (thickness greater than six millimeters) resulting in choanal stenosis (Figures 1A and B).

What is your diagnosis?

Figure 1 Vomer prominence with a thickness greater than 6 mm (mean vomer thickness of 3 mm), causing choanal stenosis. (A) Coronal view. (B) Axial view

Diagnosis

Partial choanal stenosis due to vomer prominence.

Due to persistent nasal obstruction and recurrent respiratory distress, an outfracture of the inferior turbinates was performed on day 6 of life, with sustained clinical improvement. The newborn was discharged home asymptomatic on day 12. At one month of age, the infant was reassessed by the otolaryngologist and remained clinically stable with no evidence of complications. Currently, at 23 months of age, he remains asymptomatic with no apparent recurrence of symptoms.

Discussion

Nasal obstruction is clinically relevant in neonates because they are obligate nasal breathers.1-3 Several causes should be considered for this entity, namely congenital anomalies of the nasal cavity leading to obstruction/stenosis.1) The most important and common types include choanal atresia and stenosis, congenital nasal pyriform aperture stenosis, congenital midnasal stenosis, arrhinia, and nasal septal deviation.4 Despite similarities in clinical presentation, these malformations differ mainly in the site of obstruction. Although nasal obstruction is the most common clinical manifestation, signs of respiratory distress such as retraction, nasal fluttering, cyanosis, and moaning are often present in neonates, as seen in this case.2,4,5 Feeding difficulties are also common, which may lead to poor weight gain and growth.2 Because of its life-threatening potential, the differential diagnosis with other entities such as infectious rhinitis and tumor masses must be promptly established.3

In the present case, the diagnosis was confirmed by two fundamental complementary examinations: endoscopic rhinoscopy and CT scan of the paranasal sinuses. As described in the literature, endoscopic rhinoscopy of this newborn revealed not only mucosal changes but also an inability to pass the nasofibroscope through the nasal cavity, confirming the presence of stenosis. However, the final diagnosis was made only on the basis of a CT scan, which remains the gold standard radiological examination for the diagnosis of nasal cavity disease.6

Since atresia is mainly caused by changes in the lateral wall of the choanae, there is little information on vomer variations.2 In addition, the literature on the normal morphology and dimensions of the nasal cavity in healthy children remains scarce, which may hinder the recognition of subtle structural changes.6) Likus and colleagues sought to determine the mean dimensions of the nasal structure, namely the mean vomer width (MVW), according to the age of the patient and showed that a MVW greater than three to four millimeters corresponded to a pathological change, as observed in the present case.6 However, given the difficulty in obtaining imaging data of this bone structure and the large interindividual variability, the true prevalence of vomer prominence remains to be determined.

The therapeutic approach to this condition should be tailored to the type and degree of stenosis. The use of minimally invasive strategies combined with intranasal pharmacological therapy has increased over the years and should be preferred whenever possible.5

In the present case, outfracture of the inferior turbinates was performed via anterior rhinoscopy using topical local anesthesia combined with vasoconstriction. Postoperative recovery was unremarkable, with marked improvement of symptoms and no evidence of local complications. Thus, a minimally invasive approach allowed complete and sustained symptom resolution with a low risk of associated complications and without compromising outcomes.3