Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) represent a significant advancement in the management of acid-related gastrointestinal disorders, providing effective relief and healing for conditions such as peptic ulcer disease and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Omeprazole, the first PPI to be discovered, was introduced in Europe in 1988, heralding a new era in acid suppression therapy. Since then, a range of PPIs, including lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and esomeprazole, have been identified, each offering enhanced potency in reducing gastric acidity.1

The widespread adoption of PPIs has revolutionized various clinical scenarios, including the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and prophylaxis of gastrointestinal bleeding in high-risk patients. Their efficacy and safety have contributed to their soaring popularity, making them one of the most widely prescribed drugs globally. However, this rise in PPI usage has not been without concerns.2

Over half of the patients prescribed with PPIs received these medications without clear indications for their use.3 The ease of accessibility, with the emergence of generic formulations and over-the-counter availability, has further contributed to their widespread utilization.2 Numerous studies have observed a concerning trend of increased prescription rates and inappropriate prescribing practices affecting up to 80% of PPI-treated patients.4 The allure of PPIs' efficacy has led to their overuse in inappropriate clinical contexts, such as prophylaxis of gastrointestinal bleeding in low-risk patients and usage beyond the indicated duration.2

Nevertheless, mounting evidence suggests that the indiscriminate use of PPIs may be associated with potential adverse effects, such as acute interstitial nephritis, gastric polyposis, vitamin B12 and magnesium deficiency, Clostridium difficile infection, and bacterial overgrowth in cirrhotic patients with an elevated risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.5 However, it is crucial not to discourage their prescription when appropriately indicated.6 A literature review has revealed that many studies suggesting adverse events are of low quality, subject to numerous confounding factors, and lack reproducibility. Therefore, high-quality studies are re-quired to confirm or rule out many of the proposed adverse effects.5

Moreover, the expansion of PPI prescriptions encompasses all age groups, including polymedicated elderly patients, which raises concerns regarding potential drug interactions and associated risks. The implications of such widespread and sometimes unnecessary PPI utilization extend to the financial burden on patients and public health spending.2

The objective of this study was to assess, in a sample of patients admitted to Internal Medicine wards, whether patients were taking PPIs at the time of admission and if there was a clear indication for their usage. Additionally, statistical analyses were conducted to examine whether the intake of PPIs was associated with prolonged hospitalization and mortality. Furthermore, the study aimed to analyse the unnecessary expenditure on PPIs for patients without a valid indication.

Methods

This is a retrospective study that employed a convenience sampling method, encompassing all patients observed at the hospital by the authors of the article.

The included patients were admitted between January 1st and September 30th, 2022, in Internal Medicine wards from the University Hospital Centre of Coimbra. The required clinical information for the study was obtained from discharge notes. The following data were collected: gender, age, regular medication, personal medical history, admission diagnosis, degree of dependence, presence of indication for the intake of PPIs, duration of hospitalization and mortality, intake of PPI during hospitalization and deprescription of PPIs after discharge.

The primary outcome of this study involves evaluating the usage of IBPs and its indications. Additionally, secondary outcomes include assessing the relationship between IBP usage, age increment, degree of dependence, its influence on the length of hospital stay and mortality. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26®. The t-test was used to compare continuous variables, assuming normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test, p > 0.05), and the chi-square test to compare discrete variables. All p-values were based on two-sided tests of significance. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Finally, an analysis was conducted on the annual expenses of each patient taking PPIs without an indication.

Results

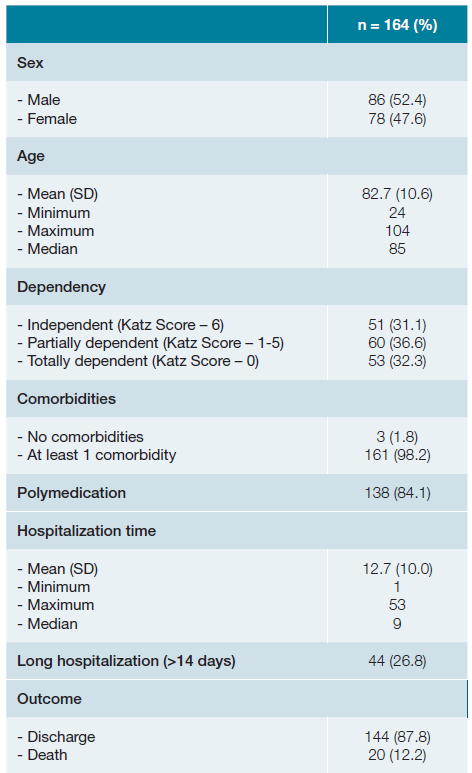

A total of 164 patients were included in the study, with the majority being male (86 [52.4%] men; 78 [47.6%] women), and the mean age was 82.7 ± 10.6 years. The youngest patient was 24 years old, while the oldest was 104 years old. The observed patient population was predominantly elderly, with approximately 116 (70.7%) of them aged 80 or older. Consequently, a high degree of dependence (according to Katz Score), comorbidity number, and polypharmacy rate were observed. General patient characteristics at admission are presented in Table 1. The most prevalent comorbidities in the evaluated population were conditions associated with a high cardiovascular risk. Among the most common were hypertension (N = 130 [79.3%]), dyslipidemia (N = 92 [56.1%]), and diabetes mellitus (N = 69 [42.1%]).

The average length of hospital stay was 12.7±10.0 days, with a minimum of 1 day and a maximum of 53 days. About half (48.2%) of the patients were hospitalized for 10 or more days. A total of 20 deaths were recorded, and in 65.0% (N = 13) of the patients, the primary admission diagnosis was respiratory tract infection. Among these cases, the SARS-CoV-2 virus was identified in 53.8% (N = 7) of them. The youngest deceased patient was a 63-year-old man with a diagnosis of advanced-stage neoplasia. Conversely, 75.0% (N = 15) of the deaths occurred in patients aged 84 or older, all of whom had some degree of dependence on activities of daily living.

Table 1 General characteristics of the study population.

When not contrarily indicated, data has been presented as N(%). SD - standard deviation

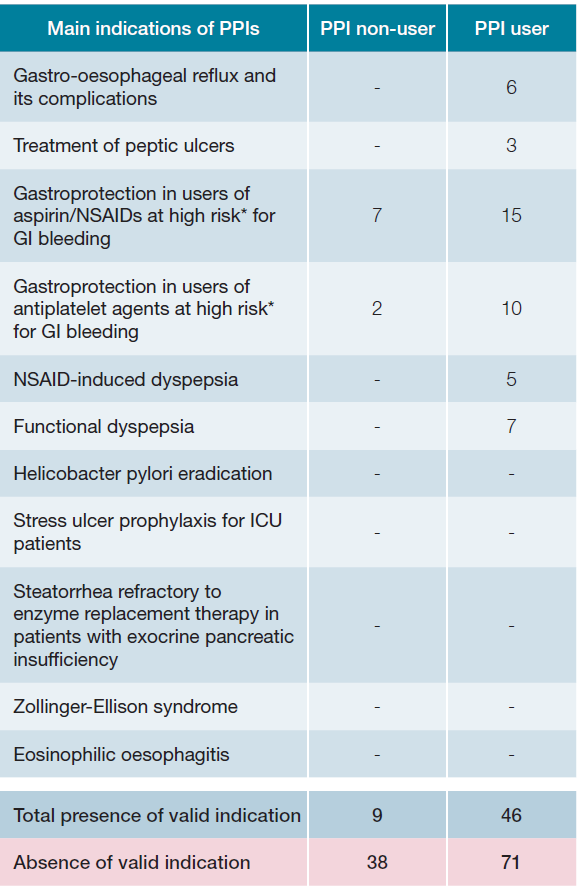

A recent review of the American Gastroenterological Association integrated all valid indications for PPIs, and the statistical analysis was based on these.7 Out of all the patients, 117 (71.3%) were on PPIs, and among them, 71 (60.7%) had no specific indication for PPI usage. Among the 47 (28.7%) patients who were not taking PPIs, 9 (19.1%) had an indication for PPI usage (Table 2).

Table 2 Distribution of indications2,7 for PPI usage.

* Prior history of upper GI bleeding, older than 60-65 years or taking concomitantly antiplatelets, anticoagulants, oral corticosteroids or second NSAID. NSAIDs - nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; GI - gastrointestinal; ICU - in-tensive care unit

The most used drugs before hospitalization, in descending order, were pantoprazole (N = 50 [42.7%]), omeprazole (N = 30 [25.6%]), esomeprazole (N = 17 [14.5%]), lansoprazole (N = 12 [10.3%]), and finally rabeprazole (N = 2 [1.7%]). The most frequent indication for those patients correctly under PPIs was the prophylaxis of gastric ulcers in high-risk patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (N = 15 [32.6%]). Among those wrongly not under PPIs, this same indication was the most prevalent (N = 7 [77.8%]). Also, there was a high rate of patients without indication under PPI who were also under anticoagulants (N = 30 [42.3%]). Table 2 describes the indications for PPI usage and the number of patients with each specific indication, both with and without PPI usage, before hospitalization.

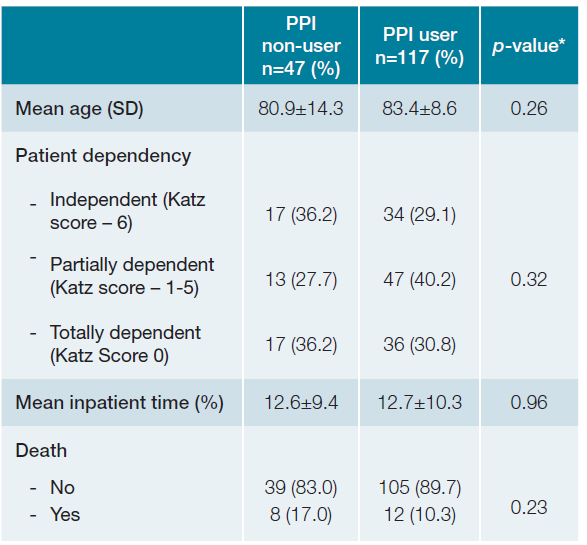

Based on the data from Table 3 the average age of patients without PPIs was 80.9 ± 14.3 years, and for those on PPIs, it was 83.4 ± 8.6 years (p-value 0.26). Therefore, in the observed sample, older patients tended to be on PPIs, al-though without statistical significance. PPI usage showed no relationship when it comes to dependency in daily activities according to Katz Score (independent patients under PPI vs non-PPI - N = 34 [29.1%], vs N = 17 [36.2%] partially dependent patients - N = 47 [40.2%] vs N = 13 [27.7%] totally dependent patients N = 36 [30.8%] vs N = 17 [36.2%] p-value 0.32). The length of hospital stay was also similar, with no apparent influence between PPI usage and the duration of hospitalization (patients without PPIs - 12.6 ± 9.4 days; patients on PPIs - 12.7 ± 10.3 days; p-value 0.96). Regarding the outcome of mortality, no difference was observed (deaths in patients without PPIs - N = 8 [17.0%] deaths in patients on PPIs - N = 12 [10.3%] p-value 0.23).

According to data from Infarmed8 collected in June 2023, each patient observed would spend, on average, approximately €25.8 yearly at pharmacies to purchase PPIs (assuming each patient took the minimum dose of a specific PPI once a day). In total, the 71 patients without an indication for PPI usage would have to spend altogether €18318 yearly. These drugs are funded by the National Health Service at 37%, whose value can be higher in the elderly, resulting in an unnecessary expenditure of at least €679.1 per year in these patients without an indication.

Table 3 Relationship between PPI usage and main assessed outcomes.

* For continuous variables independent variables t test was used; For categorical variables chi-square test was used; A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SD - standard deviation

Furthermore, after assessing the discharge notes, there was no deprescription of PPIs on those under these medications without indication. Besides, in those not taking PPIs before hospitalization (N = 47), 41 (87.2%) started after discharge. There was indication to do PPI in 9 (22.0%) and no indication in 32 (78.0%). All of those who started PPIs were prescribed pantoprazole. This contributed to additional unnecessary expenditure of public money of at least 306.0€.

Discussion

This retrospective study, based on electronic medical records, has a primary limitation due to the potential incompleteness or inaccuracies of these. There may have been patients who, despite being on PPIs, lacked a clear description of their indication for usage, leading to potential statistical bias. Additionally, this study focused on hospitalized patients from a single medical center over nine months, limiting its external validity to the non-hospitalized general population. Moreover, the studied sample consisted of elderly individuals with an average age of 82.7 ± 10.6 years, further constraining the generalizability of the results to the broader population.

The evaluated patient sample had a relatively advanced age (mean age above 80), with common pathologies related to high cardiovascular risk. Consequently, many patients were identified to be taking aspirin as primary or secondary prophylaxis, antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents. Moreover, due to their advanced age, a significant portion of these patients suffered from degenerative osteoarticular pathologies, often requiring NSAIDs. Contrarily to aspirin and NSAIDs, anticoagulants have no impact on gastric protection mechanisms and may solely elevate the risk of bleeding in individuals with a history of gastrointestinal injury. Consequently, the utilization of PPIs in anticoagulated patients, without simultaneous use of NSAIDs or antiplatelet agents, is not advisable.7 Unlike aspirin and NSAIDs, which are widely recognized for their association with gastric mucosal lesions, the gastrotoxic effects of corticosteroids are not thoroughly documented.2

A study conducted in a hospital center in Lisbon demonstrated that at admission and discharge, 36.3% and 39.4%, respectively, were on PPIs due to anticoagulant use, and 9.9% and 16.5% due to corticosteroid use alone, even though the risk for peptic ulcer disease was low.2 Other study also reported that up to 33% of patients on NSAIDs without identified risk for associated ulcers were on PPIs for preventive measures.9 Furthermore, another work showed that up to 35% of family physicians and internists recommended PPIs to low-risk individuals under NSAIDs or antiplatelets.10 Notably, it has been previously described that there is an increased likelihood of patients starting PPIs post-hospitalization, as was seen in this study.2

In our study, before admission, approximately 61% of patients on PPIs had no clear indication, a finding consistent with previous research.4 The reason for this discovery was not assessed, but it is likely related to the use of NSAIDs, antiplatelet, anticoagulants and corticosteroids without high risk for peptic ulcer disease. Additionally, it was observed that nearly 20% of patients not on PPIs had an indication for their use. The primary indication in these patients was ulcer prophylaxis in high-risk individuals, aligning with results from previous studies.2 After hospitalization, 41 patients started PPIs, 9(22.0%) of which with indications. Fortunately, these were all patients that before hospitalization were not under PPI and had valid indications. However, in 32 (78.0%) there was no valid indication and all of them were either under aspirin or anticoagulants, being the most probable reason for their start.

Pantoprazole was the most common PPI in our sample, which is favourable for our elderly and polymedicated population due to its low dependency on the CYP2C19 enzyme, reducing the risk of drug interactions.2

Regarding outcomes, in our study, PPI use was not associated with increased hospitalization time or higher mortality rates. While PPIs have been associated with multiple adverse events,5 including increased risk of neoplasia,11,12cardiovascular issues,13 and mortality,14,15contradictory results exist, with confounding factors influencing the findings. Interestingly, after 2015, there was a decline in PPI prescriptions, likely due to increased awareness among the general population and healthcare professionals regarding potential adverse events and mortality, even leading to behavioral changes in managing certain conditions, such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.4

In the Netherlands, 2%-4% of the population use PPIs long-term, with the majority having no clear indication. These expenditures accounted for a significant portion of the national healthcare budget, 271 and 290 million euros in 2005 and 2006, respectively.16,17In Spain, 6.5% of all medications dispensed were PPIs, contributing to a health expenditure of 490 million euros.3 Considering the economic challenges faced by a significant portion of the Portuguese elderly population, the unnecessary annual expense of approximately €26 per patient may be burdensome. Additionally, incorrect PPI prescriptions contribute to additional healthcare costs to the Portuguese health system. Due to cheaper generic options, expenditures have been reduced to some extent. However, the spontaneity in their prescription persists.2

Considering potential adverse events and unnecessary expenditures, it is essential to prioritize rigor and raise awareness among physicians. Family physicians have been identified as major prescribers of chronic PPIs without proper indication.4 To address this issue, various methods have been proposed and were assessed in systematic reviews, such as printed educational materials,18 appointments of a clinical opinion leader,19 regular audits,20 educational outreach visits,21 with the latter appearing to be the most effective. For instance, a French group in 2020 developed an algorithm to suspend PPIs in patients without an indication, utilizing monthly follow-up phone calls to assess medication discontinuation and the occurrence of digestive symptoms, yielding promising results with medication cessation in at least 30% of individuals.22 In 2021, the American Gastroenterological Association published recommendations for PPI discontinuation in ambulatory patients, summarizing the primary indications for their use.7There are also some tools to help clinicians improve their prescription patterns, especially in a geriatric population such as Beer’s criteria23 and STOPP/START criteria.24

Conclusion

In conclusion, multiple studies have evaluated the appropriateness of PPI use in patients. Disappointingly, a high percentage of individuals are on PPIs without any indication, potentially harming patients due to multiple potential deleterious effects and causing unnecessary healthcare expenses. Measures to combat this issue have been explored, with some showing success. The scientific community must be reminded of the existence of this problem and continue efforts to address it.