As life expectancy and focus on the quality-of-life increases, it also becomes increasingly important to study phenomena and features linked to the aging process-andropause included (Anderson et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2009; Yan, 2010). Andropause, also known as age-related hypogonadism (Anderson et al., 2002) or late-onset hypogonadism (Saad & Gooren, 2014; Wu et al., 2010), refers to the serum testosterone decline that might onset along with similar complaints and symptoms to those experienced by women during menopausal transition (Melby, 2006; Yan, 2010). This serum testosterone decline is gradual, typically around 1-2% per year after the age of 40 to 50 (Saad & Gooren, 2014), therefore making andropause a slower (Novák et al., 2002; Pines, 2011; Tan & Philip, 1999; Yan, 2010), less known and more unnoticeable process (Anderson et al., 2002; Melby, 2006; Samipoor et al., 2017; Tan & Philip, 1999; Yan, 2010) than menopause and, consequently, a less studied one (Pines, 2011).

Indeed, it seems difficult to correlate serum testosterone decline with specific symptoms (Novák et al., 2002), that in last instance may only reflect age-related and metabolic changes (Melby, 2006; Saad & Gooren, 2014; Yan, 2010) or medical conditions and disorders (Adebajo et al., 2007; Novák et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2010). According to the European Male Ageing Study (EMAS), some symptoms that seem significantly associated with low testosterone levels are decreased frequency in morning erection, low sexual desire, erectile dysfunction, inability to engage in vigorous activity (e.g., running), loss of energy, depression, and fatigue. In a syndromic perspective, the clustering of the three sexual symptoms mentioned with low testosterone levels appears to be more consistent (Wu et al., 2010). However, to our knowledge, the EMAS represent the largest study to date focusing aging in European men, and there is still a global lack of information in literature regarding andropause and men’s general and sexual health comparatively to women’s (Corona et al., 2010; Harrison, 2011; Lee et al., 2009). Specifically, the few studies that explore the existent awareness of andropause suggest little knowledge among men (Adebajo et al., 2007; Tan & Philip, 1999; Yan, 2010) and health care professionals (Adebajo et al., 2007; Harrison, 2011); even when general public and health professionals demonstrate some knowledge on the issue, misconceptions are still revealed (Anderson et al., 2002). A recent study had also suggested that when men experience symptoms of andropause they still might not acknowledge that experience as andropause (Samipoor et al., 2017). Consequently, it is not surprising that some men in andropause might be unidentified or misidentified (Adebajo et al., 2007; Novák et al., 2002).

Nevertheless, the testosterone decline calls for clinical attention, since there are studies recognizing that physical and emotional changes associated with it might impact men’s health (Lee et al., 2009; Novák et al., 2002; Saad & Gooren, 2014; Samipoor et al., 2017) and quality of life (Lee et al., 2009; Novák et al., 2002). Additionally, this phenomenon seems to be influenced by psychosocial factors. Aiming to address sexual health needs of aging couples, a recent study introduces the paradigm of “couplepause”, highlighting that menopause and andropause might be processes occurring concurrently and interdependently-with both affecting the subject’s sexual health and the sexual health of the subject’s partner, and consequently the couple’s sexual satisfaction and intimacy (Jannini & Nappi, 2018). Inclusive, erectile dysfunction had already been pointed out as a potentially shared sexual concern of couples (Fisher et al., 2009a, 2009b), and associations between women’s and men’s perceptions, beliefs and attitudes towards erectile dysfunction and its treatment had been emphasized (Fisher et al., 2009a, 2009b). It is suggested that men would more likely seek treatment if their female partner, for example, believed in erectile dysfunction as permanent and moderate to severe, held a positive view on treating erectile dysfunction, or had higher sexual satisfaction before erectile dysfunction had emerged (Fisher et al., 2009b). In fact, women’s views on andropause might be particularly important, since men and women seem to behave differently in information-seeking, with women tending to adopt a mediator role on their families-looking for health information both regarding themselves and others within the family (Harrison, 2011). This might be because women, contrarily to men, are more used to medical care and medical procedures throughout life, firstly going to the doctor to contraceptives’ prescription during adolescence, then being accompanied regarding pregnancy, and then regarding menopause (Gooren, 2000). Consequently, it might be hypostatized that in some cases women will adopt an active role in men’s coping with andropause.

The Common-Sense Model (Leventhal et al., 1998) - also recognized in the literature as Self-Regulation Model - has been suggested to understand the menopausal experience among women since it accounts for cognitive representations of menopause, and for how women cope with related symptoms (Chou & Schneider, 2012; Hunter & O’Dea, 2001). Thus, Leventhal et al. (2016) emphasize the several dimensions of the model namely: 1) identity which focus the attributed label and symptoms of the menopausal experience, 2) perceived consequences which account for perceived severity of menopause and its impact (including negative and positive consequences), 3) cause, which entails the source (i.e., hormone changes) of menopause, 4) control, that is the perceived self-management of menopause, and 5) time frame which regards to the perceived short or long duration of menopause. However, the suitability of this to an analogous process such as andropause has not yet been studied.

Considering that psychosocial factors have some impact on andropause, potentially affecting both men’s health and conjugal relationships, and since women may be particularly active in health information seeking, the present study aims 1) to assess Portuguese women’s representations of andropause, 2) to explore the suitability of the Leventhal et al. (2016) model explaining women’s andropause representations, and 3) to explore potential associations between women’s sociodemographic characteristics and pertinent emergent categories regarding andropause representations.

Methods

Participants

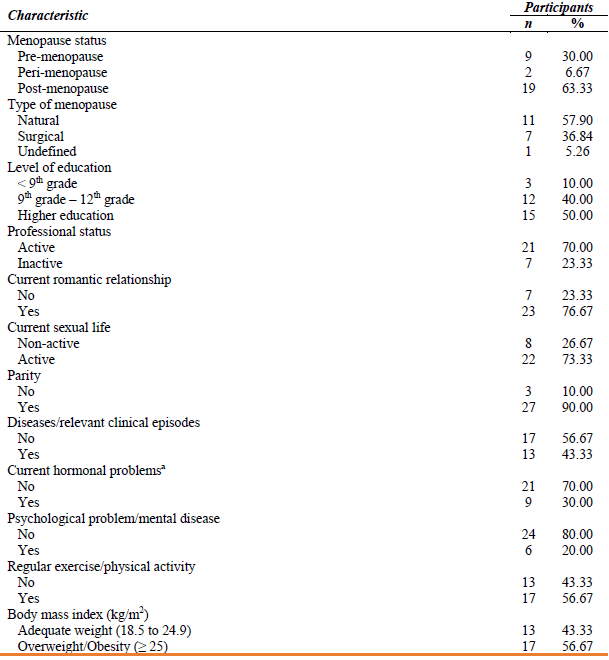

The present study was based on an intentional non-probabilistic sample of 30 Portuguese heterosexual women with ages ranging from 40 to 86 years old (M = 52.97, SD = 10.17). Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the sample.

Table 1 Participant’s sociodemographic, health, lifestyle and menopause-related variables.

Nota: ª related to thyroid, suprarenal, pituitary, or other.

Material

A protocol of several questionnaires to assess participant’s sociodemographic (e.g., age, level of education), health (e.g., diseases and relevant clinical episodes), lifestyle (e.g., physical exercise) and menopause-related (e.g., menopausal status and type of menopause) characterization was prepared by the authors of this research. To determine menopausal status, Harlow et al. (2012) criteria was followed and women were defined as pre-menopausal (i.e., absence of modifications in the menstrual cycle), peri-menopausal (having variable menstrual cycle length and/or amenorrhea periods superior to 60 days) or post-menopausal (an amenorrhea period equal or superior to 12 months).

A semi-structured interview was also performed. This regarded andropause representations (“What is andropause for you?”), perceived positive consequences of andropause (“Does andropause have any positive consequences? If so, which ones?”), and perceived negative consequences of andropause (“Does andropause have any negative consequences? If so, which ones?”), based on the conclusions of Hunter and O’Dea (2001) regarding the menopausal experience.

Procedure

The Health Committee of William James Center for Research, ISPA - Instituto Universitário approved the study. This study is part of a research project named “Experiências de Vida | Saúde na Adultícia” [Life Experiences | Health in Adulthood] (EVISA). The first stage of this study included women aged above 40 years and above, and multiple socio-demographic, health, lifestyle and menopause-related variables were assessed. At the end of this stage, participants were invited to leave their contact details if they would be available to be interviewed in a second stage regarding menopause and andropause representations. A total of 30 out of 59 women who had left their contact details proceeded to this second stage of this study (see Figure 1). Interviews were conducted by phone call, with the participants’ consent and the authorization for audio recording and subsequent treatment of the data, at the beginning of the contact. Confidentiality was assured along with the possibility for withdrawal at any moment without any consequences. The privacy and suitability of the room where the interview was conducted were assured. Anonymity was secured by attributing alpha-numeric codes to participants and their transcribed interviews. This research followed the standards of the Portuguese Psychologists Association (2011) and the American Psychological Association (2003) regarding the ethical treatment of participants and ethical validation of the project was given by the Translational Group Coordination of the William James Center for Research.

Interviews were transcribed in a verbal and non-verbal content (e.g., pauses and laughter) using the Directed Approach, qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This approach also known as a deductive use of theory (Potter & Levine‐Donnerstein, 1999) or as a deductive category application (Mayring, 2000), allows the identification of both units of the interviews and the frequency of each category regarding an initial coding scheme being developed and operationalized according to existing theory and prior research; this coding scheme may then be refined throughout the analysis.

Accordingly, the coding procedure followed was: (a) identification of mutually exclusive emerging categories regarding the latent content of each of the three pre-existing categories (Andropause Identity, Andropause Positive Consequences, and Andropause Negative Consequences); (b) conception of customized codes; (c) analysis and identification of speech excerpts which met the emerging categories; and (d) evaluation of coding decisions made by comparing speech excerpts with categories’ theoretical definitions and with other speech excerpts within the existing categories-in some cases either extending the scope of certain categories or re-allocating some speech excerpts in more theoretical suitable categories. MAXQDA software (v. 2012) was used to code the interviews’ content, and this was made in a dependent way by two evaluators (psychologists) of 28 interviews. To assess inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s kappa coefficient, κ), the last two transcribed interviews were coded in an independent way by two evaluators. However, as the reliability assessment indicated a fair agreement (κ = .28, p = .014), final codification of these interviews was afterwards achieved by consensus.

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was also performed to explore associations between the emergent categories derived from the Directed Qualitative Content Analysis and to acknowledge potential clusters regarding women’s conceptualization of andropause. It was established as a criterion to only consider emergent categories that were mentioned by at least three participants (10% of the sample).

Finally, Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to test differences regarding the frequency of emergent categories, between groups of presence-absence of specific sociodemographic variables among our sample. Descriptive analysis, Cohen’s kappa coefficient, MCA and Mann-Whitney U tests were done using SPSS software (v. 25, IBM Corp. Armonk, NY).

Results

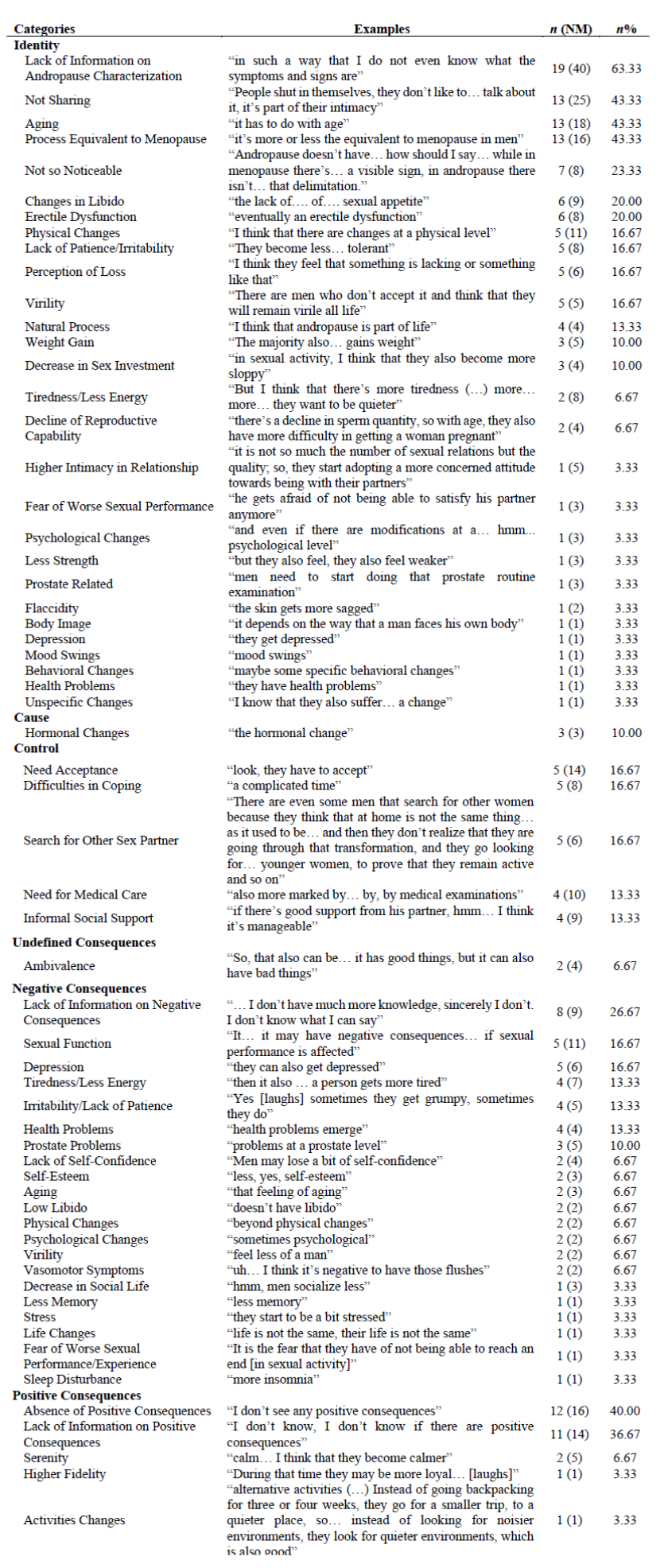

Regarding andropause’s Identity dimension [having Leventhal et al. (2016) model as standard], the qualitative content analysis of the interviews revealed that an Undefined identity stood out the most, with the majority of women of this sample reporting a lack of information on andropause characterization. Another Identity category frequently mentioned was Not Sharing. The only category that was identified regarding the Cause of andropause was Hormonal Changes. Some categories regarding the Control dimension of Leventhal et al. (2016) model were also identified in women’s speech, although no categories were identified regarding the Time frame dimension. In what concerns the negative perceived consequences of andropause, the most frequently reported category was Sexual Function, although a higher number of women reported a lack of information on Negative Consequences of andropause. Concerning perceived Positive Consequences of andropause, few women were able to identify any; consequently, the undefined consequences’ categories Absence of Positive Consequences and Lack of Information on Positive Consequences revealed to be the most frequent ones. All emergent categories, along with its frequencies and with speech excerpts examples of each category are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Emergent categories resulting from the directed content analysis regarding andropause representations.

Note: n = number of women who mentioned the category; NM = number of times the category was mentioned; n% = percentage of women who mentioned the category.

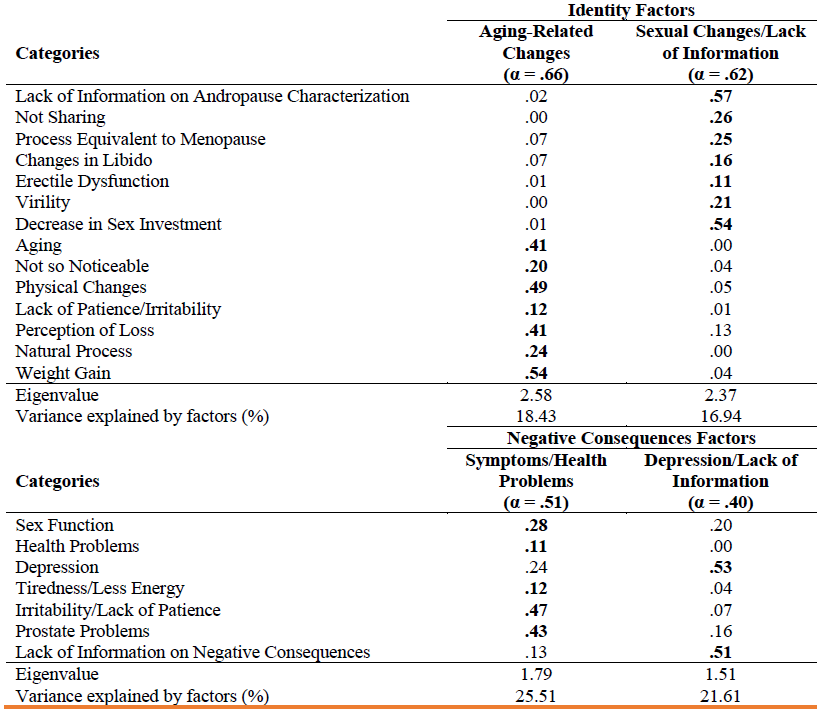

Two MCA were performed, one regarding Identity emergent categories and other- regarding perceived Negative Consequences of andropause. MCA was not performed for Cause, Control and perceived Positive Consequences of andropause due to their reduced total number of categories.

Table 3 Bi-dimensional model for the identity of andropause and for negative perceived consequences of andropause

A bi-dimensional model was found for Identity of andropause (Table 3). In this model, the identified factors-Aging-Related Changes and Sexual Changes/Lack of Information-accounted for 35.37% of the variance of Identity of andropause. Regarding perceived Negative Consequences of andropause, a bi-dimensional model was also found. In this model, the identified factors-Symptoms/Health Problems and Depression/Lack of Information-accounted for 47.12% of the variance of perceived Negative Consequences of andropause.

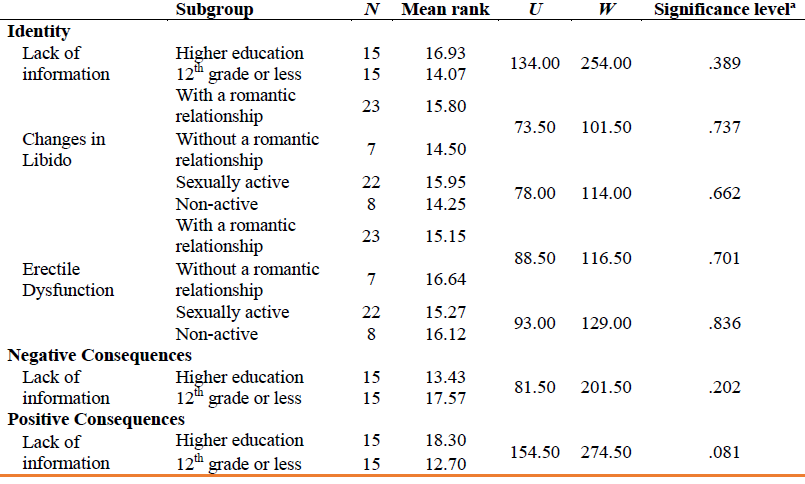

Finally, differences in the frequency of emergent categories were assessed with Mann-Whitney U Tests, particularly regarding frequent emergent categories between groups of presence-absence of sociodemographic variables. No significant differences were found in any of the Mann-Whitney U Tests performed (as shown in Table 4).

Specifically, when considering the Identity of andropause, no differences were revealed in the frequency of the Lack of Information category between women with higher education and women with the 12th grade or less; in the frequency of the Changes in Libido and Erectile Dysfunction categories, neither between women currently in a romantic relationship and women who were not, nor between sexually active and sexually non-active women.

Table 4 Andropause representations: comparisons of participants with different characteristics

Note: ª p-value (two-tailed) from Mann-Whitney U test.

Concerning perceived Negative Consequences of andropause and perceived Positive Consequences of andropause, our results also revealed no differences in the frequency of the Lack of Information category between women with higher education and women with the 12th grade or less.

Discussion

The principal aim of this study was to explore Portuguese heterosexual women’s representations of andropause and the potential suitability of the Leventhal et al. (2016) model in explaining those representations. According to our results, most of the Common-Sense Model dimensions-specifically, Identity, perceived Consequences, Control and Cause-were supported as suitable to explain andropause from women’s perspective, having these several content similarities as those suggested by Hunter and O’Dea (2001) and Pimenta et al. (2020) in explaining menopause.

Regarding emergent categories of the qualitative content analysis for Identity of andropause, a Lack of Information on andropause characterization prevailed among the high majority of women, being the next most frequent category mentioned related to Not Sharing-that is, a lack of social dialogue and sharing on the phenomenon. Similarly, the most frequent category on perceived Negative Consequences was again Lack of Information, being this followed by a category related to Sexual Function. Concerning perceived Positive Consequences, most women reported an absence of those and, once again, Lack of Information. Therefore, together these results are in line with the already highlighted general lack of knowledge and awareness on andropause and men’s health (Corona et al., 2010; Harrison, 2011; Lee et al., 2009), with the phenomenon sometimes not being correctly identified (Pines, 2011). This suggests the need for more research and information on what characterizes andropause and its possible consequences, especially considering that women tend to be health information-seekers for their own and for those in their families (Harrison, 2011), with their views and attitudes influencing those of men towards erectile dysfunction (Fisher et al., 2009a, 2009b)-a symptom frequently linked to andropause (Wu et al., 2010). Indeed, the fact that women in our sample perceived sexual function as a negatively impacted feature in men during andropause, and that several women perceived no positive consequences, this study alerts for the possibility of men not only experiencing andropause without recognizing it but also experiencing it negatively.

Still considering the qualitative content analysis performed, categories related to Control and Cause of andropause were also identified; however, no Time Frame references were found, which is also in accordance with the literature. Specifically, several emergent categories of the Control dimension mentioned by women were similar to those found by Hunter and O’Dea (2001) and Pimenta et al. (2020) to explain menopause (e.g., need for acceptance, difficulties in coping); moreover, the fact that there were no time frame mentions and that hormonal changes were pointed as the cause of andropause is in line with andropause resulting from a gradual decline in serum testosterone levels (Melby, 2006; Saad & Gooren, 2014; Yan, 2010), which is sometimes a more unnoticeable process in comparison to menopause (Anderson et al., 2002; Melby, 2006; Samipoor et al., 2017; Tan & Philip, 1999; Yan, 2010).

The two-dimensional models found for Identity and perceived Negative Consequences of andropause through MCA helped to clarify the associations between frequent categories mentioned by women. Regarding the two-dimensional model for Identity of andropause, the first factor, composed by categories linked to Aging-related changes such as physical changes, perception of loss and weight gain, might have emerged since these are diffuse symptoms of androgen deficiency that are identified by women as being part of the aging process of men, including several biological and social changes and losses (World Health Organization, 2015). The second factor, composed by categories linked to Sexual changes and Lack of information, such as the lack social dialogue and sharing regarding andropause, comparison of andropause with menopause as an equivalent process, changes in libido and a decrease in sex investment, seems to reflect that if not associated with age-related changes then it must be associated with physical changes (i.e., impaired sexual performance) that have a significant impact on the quality of life of both men and women (Novák et al., 2002). Together, these results reinforce andropause as a phenomenon that lacks awareness (Corona et al., 2010; Harrison, 2011; Lee et al., 2009), possibly confounded with the aging process (Melby, 2006; Saad & Gooren, 2014; Yan, 2010) and more consistently related with sexual features (Wu et al., 2010).

Similar suggestions are made by the two-dimensional model found for perceived Negative Consequences of andropause, where the first factor is composed by categories that relate to symptoms and health problems that, although in line with the andropause’ symptoms pointed by the EMAS study (Wu et al., 2010), are not necessarily specific of andropause-such as tiredness/less energy and irritability/lack of patience-and the second factor is composed of depression and lack of information on negative consequences of andropause, which together seem associated with non-specific complaints (Novák et al., 2002; Pines, 2011). Andropause is associated with a largely non-specific sexual, physical, and psychological symptoms which are often identified in androgen deficiency of aging men in general (Huhtaniemi, 2014). Nevertheless, depression as a clinical manifestation of aging and of androgen deficiency is many often mis-diagnosticated over andropause (Harrison, 2011; Jakiel et al., 2015; Novák et al., 2002), prevailing a misleading conception for perceiving symptoms of andropause as being symptoms of depression in older men.

No differences were found through the Mann-Whitney U tests regarding the frequency that Lack of Information about andropause (which emerged both in Identity and Consequences) among women with different levels of education. This once more suggests the lack of information on andropause is not dependent on education level and reinforces the need to have more information available about the phenomenon. Further, no differences were found through the Mann-Whitney U tests regarding the frequency of Changes in Libido (identity) and Erectile Dysfunction (identity) among women who were and who were not in a romantic relationship, and among women who were and who were not sexually active; this also suggests that these are stable representations among women, regardless of relationship/sexual activity status.

This consequently might call for some attention in the field of health-related information, because it shows the lack of information about andropause among women. Additionally, if andropause and menopause can occur concurrently and interdependently, affecting the sexual health of the couple it would be of significant importance to involve men’s partners, since there is proof of the significance that a partner (namely in this study with heterosexual men, a women) can have for the men’s satisfaction and quality of life (Fisher et al., 2005).

Some limitations of this research must be considered. Although the suitability of the Leventhal et al. (2016) model to explain andropause seems to be supported, this suitability must be considered a preliminary result, since we had only considered women’s perspectives and had a non-probabilistic convenience sample of 30 women. Therefore, and despite the importance of women views on andropause, future research should be pursued to also assess men’s perspectives on the phenomenon, and eventually to compare couple’s perspectives. This is also a gap in the literature since few are the studies that have evaluated how the representations of andropause can affect men’s sexual health and their intimate relationships (i.e., sexual satisfaction) (Jannini & Nappi, 2018).

These preliminary results concerning the representations of women about the andropause process contribute to the research in this scope - which is scarce in the Portuguese population - and, also to clinical practice, allowing to guide future interventions focusing couples that are facing andropause and/or menopause. Future studies with other cultures are needed to better understand these outcomes.

Author contributions

Filipa Pimenta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review and editing

Maria Meireles Ramos: Data curation, Writing - Original draft

Carolina Silva: Data curation

Pedro Alexandre Costa: Conceptualization, Methodology

Inês Queiroz-Garcia: Writing - Original draft, Writing - Review and editing

João Marôco: Supervision, Formal Analysis

Isabel Leal: Supervision, Methodology