Body image is a multidimensional psychological construct that refers to people's perceptions and attitudes about their own body and appearance (Cash, 2004, 2011, 2012; Cash & Pruzinsky, 1990, 2002; Thompson et al., 1999). According to Cash (1994, 2002a, 2002b, 2004), body-related perceptions are associated with an evaluative process that includes a self-ideal discrepancy that leads to (dis)satisfaction concerning one's own body or appearance. Attitudes, in turn, are related to the cognitive-behavioural salience of one's appearance or the importance and investment that people will ascribe to their appearance (Cash et al., 2004).

In the past, the research on body image has been centred on body dissatisfaction and concerns with weight, shape and appearance (e.g., Gardner et al., 2009; Stice et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 1995; Stevens et al., 2016) and associated pathology, such as eating disorders (Cruz-Sáez, Pascual et al., Wilson, 2006). In contrast, recent studies have targeted body satisfaction (Becker et al., 2017; Tiggemann & McCourt, 2013; Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015) and health-related behaviours and benefits (Andrew et al., 2014; Larson et al., 2012).

Body dissatisfaction has been more extensively studied in adolescent girls and women (Bailey et al., 2016; Fiske et al., 2014; Mond et al., 2013). However, more recently, the research in the field has been focusing on men and women, which enabled us to identify at the same time similarities and differences.

The similarities found suggested that men might be as vulnerable to body image disturbances and dysfunctional behaviours such as severe dieting and exercise as are women (Cafri et al., 2005; Malik et al., 2019; Parent et al., 2016). Additionally, although there is a social pressure to achieve esthetical social standards for both sexes, the standards are different: women desire to decrease and become smaller, and men desire to increase (muscular mass) and become stronger (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001a; McCabe et al., 2002; Stanford & McCabe, 2005). Past body image studies with adults have predominantly focused on young adults, namely college students, and research with older adults is still reduced (Grogan, 2011).

Measurement of Body Image and Appearance

Concerning the measurement of body image and appearance constructs, few instruments were found. Most instruments were developed to measure individual physical appearance (e.g., Physical Appearance Perfectionism scale - PAPS, Yang & Stoeber, 2012; Genital Appearance Satisfaction Scale, Bramwell & Morland, 2009; Muscle Appearance Satisfaction Scale - MASS (Mayville et al., 2002); Physical Appearance State and Trait Anxiety Scale - PASTAS (Reed et al., 1991; Satisfaction with Appearance Scale - SWAP, Lawrence et al., 1998), or physical appearance in a social context (e.g., Sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire - SATAQ (Heinberg et al, 1995; Physical Appearance Related Teasing Scale - PARTS (Thompson et al., 1991; Verbal Commentary on Physical Appearance scale - VCOPAS (Herbozo & Thompson, 2006) or both (e.g., Social Appearance Anxiety Scale - SAAS, Hart et al., 2008). Most of these measures are specifically related to physical appearance and used with young adults.

Few instruments oriented to a much broader conceptualization of appearance were found. The Beliefs About Appearan4ce Scale (BAAS: Spangler & Stice, 2001) was designed to measure dysfunctional attitudes about bodily appearance and determine the intensity of body image awareness (including interpersonal interactions, personal achievement, self-perception, and emotions). This scale, composed of 20 items, was validated for both men and women and for a young population, including adolescents, college students and young adults. Later, a study with middle-aged women was also performed (Liechty et al., 2006).

The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire-Appearance Scales (MBSRQ-AS; Brown et al., 1990; Cash, 2000), comprising 34 items organised in five sub-scales (appearance evaluation, appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, self-classified weight, and body areas satisfaction scale). It was validated with college students (under 30 years) of both sexes.

The 20-item Appearance Schemas Inventory-Revised (ASI-R: Cash et al., 2004) assesses two schematic investment facets on appearance: Self-Evaluative Salience and Motivational Salience. It was validated with a college student sample of both sexes.

The three measures were mainly validated with college-aged samples. Only one study has focused the appearance construct on a middle-aged population (namely, BAAS, which has a clinical purpose).

In the present study, we intended to develop a scale that aims to overcome specific gaps in the literature. Thus, it was developed and tested with a middle-aged sample composed of both men and women. It looks to assess general appearance, not the specificity of the ageing process since the adequacy for both sexes was also a concern (that is, considering the dissimilarities of the ageing process between sexes, this scale is intended to be wide enough to be valid for both men and women). Therefore, this study aims to develop and validate the Appearance Beliefs Scale, an instrument designed to assess beliefs regarding appearance valid for both middle-aged women and men.

Method

Participants

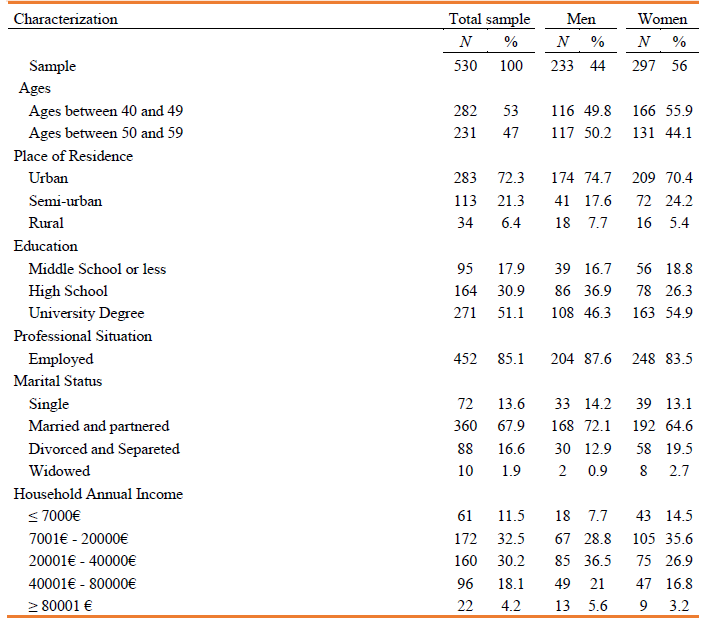

This study included 530 adult participants (233 men and 297 women) from 20 Continental Portugal and Islands districts. The inclusion criterion for this study was that the participants' age ranged between 40 and 59 years old. For men, the mean age was 48,94 (SD=5.35), and for women was 48.66 (SD=5.48). Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

Measures

Participants were asked to complete a sociodemographic questionnaire, including age, sex, and two psychological measures.

Beliefs about Appearance. The Appearance Beliefs Scale (ABS) presented 12 items (e.g., "My image is an important part of who I am"), which were generated based on 1) pre-existing instruments, 2) a literature review in the field, and 3) a panel of three experts in the field of psychometrics and body-related constructs. The measure asks participants to rate their level of agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1 - totally disagree to 5 - totally agree).

Body Image. The Body Image and Body Change Inventory (Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2002) has several sub-scales; however, the present study only used the following dimensions:(1) body image importance (e.g.," It is much easier to manage my daily tasks when I feel good about the way I look."; and (2) body image satisfaction (e.g., "I am satisfied with the way I look".) Responses were given in a 5-point Likert-type scale, with scores ranging from "extremely important" to "not important at all" in the importance dimension, and from "extremely unsatisfied" to "extremely satisfied" in the satisfaction dimension.

Procedures

Both online and paper versions of the questionnaire were assembled. The online version was disseminated through the research team contacts and social media networks (e.g., Facebook, blogs directed to the middle-aged population). The paper version was also distributed in schools and universities (the questionnaires and informed consents were given to students in envelopes to be filled, sealed by their family members, and afterwards returned to the research team). The questionnaires were also distributed in local councils, activities centres and private companies.

This study was part of a larger research (EVISA - Experiências de Vida I Saúde na Adultícia / Health and Life Experiences in Adulthood).

All procedures followed the ethical standards stated by the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (APA, 2013; OPP, 2011). The study's aims were explained in the informed consent form, which emphasised that participation in the research was voluntary and that participants could interrupt their collaboration at any time without justification or consequences.

Data Analysis

Sensitivity was explored through the analysis of minimum and maximum values, skewness, and kurtosis. Values are expected to range through the overall Likert-type scales (from the minimum to the maximum scores), and skewness and kurtosis are expected to have absolute values below three and seven, respectively, assuring that they would not compromise CFA results (Kline, 2015; Marôco, 2014).

It was conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the ABS construct validity. Descriptive analysis and CFA were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26 and IBM SPSS AMOS (v.26). The quality of the fit model was evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1998), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SMRM) (Marôco, 2014). For reference, values above .90 on the CFI and below .10 on the RMSEA indicate an acceptable model fit (Hair et al., 2006).

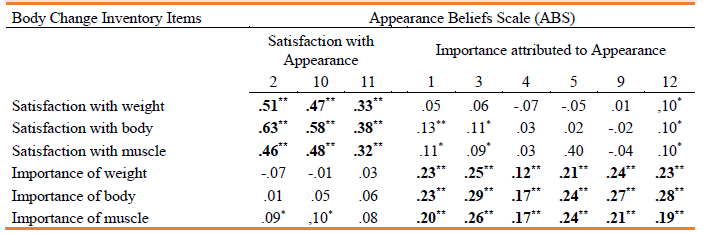

Criterion validity was explored through concurrent-oriented validity of scales, using Pearson's correlation with similar constructs, namely with the Body Image and Body Change Inventory.

The convergent validity of the ABS was analysed through the average variance extracted (AVE). The constructs' convergent validity evidence was assumed for values of AVE > 0.5 (Marôco, 2014). Discriminant validity was explored by comparing the inter-factor´s squared correlation (r2) with the AVE of each individual factor. Reliability was evaluated using composite reliability (CR). Values of CR ≥ 0.70 indicate adequate reliability (Chin, 1998; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2005).

Additionally, a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) was performed at the best model to test for model invariance of the ABS between sex and age groups (40-49 years old and 50-59 years old).

Results

Sensitivity

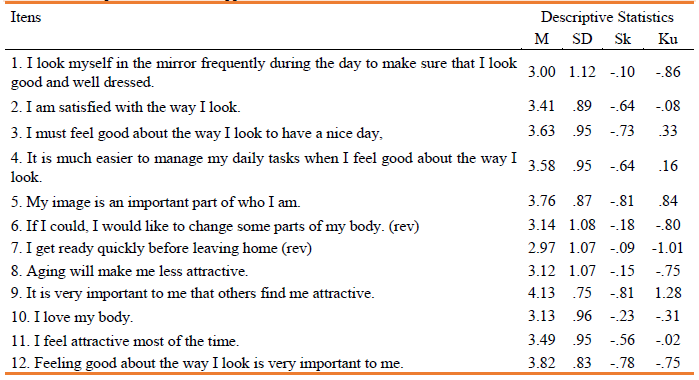

To address sensitivity, the items response range was explored; all items presented answers at all points of the scale (from the minimum to the maximum value). Table 2 presents means, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis. No substantial deviations from the normal distribution were considered for absolute values of Ku smaller than seven and Sk smaller than three.

Construct validity

Factorial validity

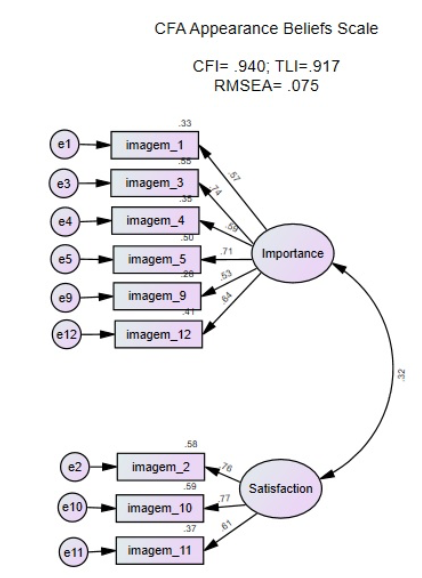

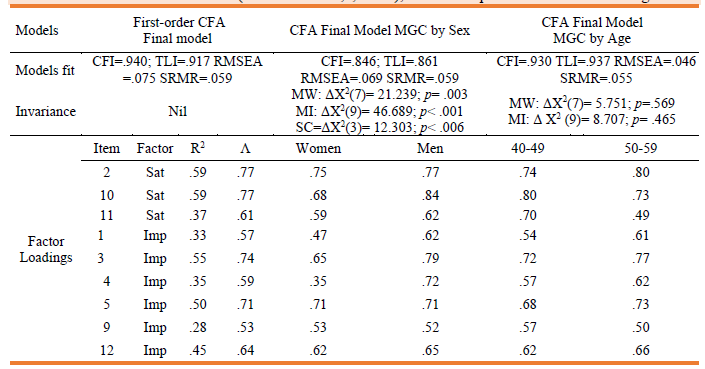

Confirmatory Factor Analysis indicated a first-order hierarchical structure with two first-order factors: Importance attributed to appearance and Satisfaction with appearance. All items presented both good factor weights (≥.50), except for item (λ = .46, R 2 =.22). The quality of the model was good (CFI=.940; TLI=.917; RMSEA =.075; SRMR=.059).

Table 3 shows the first-order CFA final model fit (without items 6, 7, 8) and the factor loading and the MGCFA for sex groups and age groups. The final model is shown in figure 1 (the measurement model did not need any additional adjustment).

Table 3 Is First order CFA models (without items 6,7, and 8), Multi-Group CFA and Factor Loadings

Note. CFA=Confirmatory Factor Analysis; MGC=Multi-group comparison; Sat = Satisfaction subscale; Imp=Importance subscale. MW= Measurement weights; MI= Measurement intercepts; SC=Structural Covariances

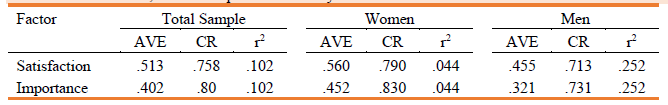

The Satisfaction with Appearance factor and Importance attributed to Appearance factor presented adequate AVE scores (i.e., ≥.50, according to Fornell & Larcker, 1981), indicating convergent validity. Discriminant validity was also verified in both factors since the AVE scores were both higher than the squared correlation between factors (r 2=.102) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Both factors presented high Composite Reliability scores (i.e., ≥ .70, Chin, 1998; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2005), indicating good internal consistency (Table 4).

Concurrent Validity

The association among all items was positive and significant, as expected (see Table 5).

Invariance Analysis

The constrained measurement model with factorial weights (l) and intercepts (i) between age groups both did not present a significantly worse adjustment than the unconstrained measurement model (Δχ2λ(7)=5.751, p=.569; Δχ2i(9)=8.707, p=.465; however, this did not occur within sex groups (Δχ2λ(7)=21.239, p=.003; Δχ2i(9)=49.689, p<.001; Δχ2cov(3)=12.303, p=.006). Table 3 shows the models fit and factor loading for both sex and age comparisons.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to develop and validate a measure of Appearance - The Appearance Beliefs Scale (ABS). Items 6 ("If I could, I would like to change some parts of my body"), 7 ("I get ready quickly before leaving home") and 8 ("Aging will make me less attractive") showed very low factorial weights in either dimension. Confirmatory Factor Analysis indicated a first-order structure with two first-order factors: Importance attributed to Appearance and Satisfaction with Appearance. This first-order structure presented good fit indices. The dimensions Importance attributed to Appearance and Satisfaction with Appearance met the literature since, according to Cash (1994, 2002a, 2002b, 2004), satisfaction is essential to the evaluative perception's process, and the importance is related to the investment that people will ascribe to their own appearance in the attitudinal process.

The two-dimension factorial structure was confirmed in the total sample, as well as in the subsamples. The invariance analysis (MGCFA) was performed to verify the stability of both sex and age groups. Model invariance was not confirmed between men and women. However, this difference between sex groups was not unexpected (Untas et al., 2009). According to Cash et al. (2004), this difference is likely due to a culturally demanding female beauty/body ideal systematically emphasised by the media.

On the one hand, media conveys that achievement of the ideal body is an expression of women's value related to happiness, love, and social status. On the other hand, the pressure on men is more diversified, exploring men's value, not only associated with a fit body, but also with wealth and intelligence expressions (Tiggemann, 2002). Moreover, literature documents that men and women have a different conceptualization of the appearance construct. Women's ideal body is thinner, while men's ideal is muscular (Andersen et al., 2000; Cafri et al., 2004; Vartanian et al., 2001). To this ideal male body, both penis size and height (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Costa et al., 2016; Tiggemann et al., 2008) are also perceived as relevant for the physical attractiveness construct (McCreary et al., 2004). In contrast, the female body ideal is focused on signifiers of "sexiness" in the body shape, a consequence of the objectification of women, so large breasts, long legs, long hair, thin waist, and rounded buttocks are perceived as relevant for physical attractiveness in women (Murnen, 2011). Despite the different construct representations, the measurement model was confirmed fit for both sexes, meaning that the Appearance Beliefs Scale presents items that women and men can answer.

In contrast, model invariance was verified between age groups, which indicates that the scale is stable across mid-age stages. The ABS was developed to be sensitive to middle-aged individuals' experiences, during which several hormonal, body changes and ageing-related consequences might be felt. Since the changes and consequences associated with mid-life differ not only between sexes but also between individuals (Charles et al., 2001), the ABS intended to access not the specific middle-age changes but the body-appearance satisfaction and importance. Moreover, this short measure appears to be valid for both women and men across this life cycle stage and suitable to access beliefs regarding appearance in different contexts.

Correlation analyses were conducted to determine the degree of association of the Appearance Beliefs Scale with the theoretically related measure, Body Image and Body Change Inventory, precisely two dimensions that also assess satisfaction with and importance of body appearance. The association between both Satisfaction and Importance items of the two instruments (Appearance Beliefs Scale and Body Image and Body Change Inventory) were positive and significant, as expected. However, the positive and significant association presented between both Importance dimensions was generally weak. Therefore, both sub-constructs of importance (of the two different questionnaires) have subtle underlying theoretical differences. The importance factor of the Body Image and Body Change Inventory is focused on physical appearance.

In contrast, the importance factor of the Appearance Beliefs Scale is oriented to more extensive aspects of appearance (e.g., "To have a nice day, I have to feel good about the way I look/my appearance", "It is much easier to manage my daily tasks when I feel good about the way I look"). For instance, the Appearance Beliefs Questionnaire includes items assessing attractiveness (item 9), schemas (items 5 and 12) and appearance beliefs that include emotional consequences (items 1, 3 and 4) of behaviours. Since it is composed of items that assess not physical aspects of body but one's appearance beliefs, respondents' answers will be related not strictly with their physical body but with what they subjectively value in their physical appearance.

Additionally, the dimension Importance presented weak convergent factor validity; this may be explained by a previously discussed feature (namely, the heterogeneity of items that compose the sub-scale). Nonetheless, since all the other values were within acceptable ranges, the AVE values of importance factor may be accepted. Hence, the Appearance Beliefs Scale is suitable for both middle-aged men and women. This wide-ranging capacity to reach different sexes and ages consists of one of the strengths of this scale.

Some limitations should be accounted for, mainly that the sample was non-probabilistic and collected both online and in paper-and-pencil, representing a discrepancy in sample procedure. One additional limitation refers to a small initial pull of items.

In conclusion, this scale was developed to assess beliefs about appearance in middle-age. The analyses evidenced a first-order hierarchical structure with good psychometric properties. The results showed good reliability (both internal consistency and sensitivity), as well as construct validities. However, considering the study's methodological characteristics and limitations, these results should be interpreted, which do not allow generalization. Therefore, it is necessary to test the Appearance Beliefs Scale again in future studies, exploring its psychometric properties in different samples, including adults from young and late adulthood. Comparisons between these different developmental stages could provide pertinent information about generational differences in appearance-related beliefs.

Contribuição dos autores

Filipa Pimenta: Administração do projeto; Concetualização; Curadoria dos dados; Investigação; Metodologia; Supervisão; Redação do rascunho original; revisão.

Paula Mangia: Curadoria dos dados; Análise formal, Investigação; Metodologia.

Pedro Alexandre Costa: Administração do Projeto; Curadoria dos dados; Análise formal, Investigação; Metodologia.

João Marôco: Curadoria dos dados; Análise formal, Investigação; Metodologia.

Marta Porto: Curadoria dos dados; Análise formal, Investigação; Metodologia.

Isabel Leal: Administração do projeto; Supervisão; Revisão.