Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecological malignancy in developed countries and the 4th most frequently diagnosed cancer in women, accounting for 6% of all malignancies in this population1,2. In Portugal, its incidence is 5.2/100.000 and expected to rise due to aging population and the increase in obesity and metabolic syndrome rates, which strongly correlate with an increased risk of developing endometrial cancer1,3. Upon diagnosis, most women (80%) have disease confined to the uterus (stage FIGO I) 1,3,4. Prognosis considerably worsens when regional or metastatic disease is present (5 year overall survival rates of 68% and 17%, respectively) 1. Both histology and depth of myometrium invasion are important in risk stratification into low, intermediate and high risk disease, which translates to the likelihood of lymph node metastasis and the presence of disease outside the pelvis. Disease extension is best assessed using pelvic gynecological MRI4,5. Lymph node staging defines recurrence risk and helps clinicians decide on adjuvant treatment. Surgical staging has been the standard modality for evaluation of metastatic disease, including total hysterectomy (TH) and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) and complete pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy when indicated1,3,4. However, randomized trials did not demonstrate a survival benefit among patients with early stage EC undergoing systematic lymphadenectomy, which can be associated with significant morbidity (nerve and vascular injuries and higher incidence of postoperative lymphedema and lymphocyst formation) and longer operative time. 6,7;8-11 Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy alone in EC has emerged as an alternative to systematic lymphadenectomy1,3,4;11-16. The SLN should be defined as the juxtauterine lymph node with an afferent lymph vessel in each lymphatic pathway13;17. Indocyanin green (ICG) enables the identification of both lymph vessels and lymph nodes and is associated with the highest bilateral SLN detection rate, compared to others4,11,13,15,18,19. Sentinel lymph node biopsy also allows for detection of low volume metastatic disease, in a process known as ultrastaging, thus further increasing the detection rate of metastatic disease4,17,20.

Methods

A prospective cohort study to assess the feasibility of SLN mapping in endometrial cancer using ICG and near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence is ongoing at the au-thors’ Gynaecological Oncology Unit. To our knowledge, this is the first published series of SLN mapping with ICG in endometrial cancer a Portuguese hospital. Data from all women with primary endometrial cancer considered eligible for comprehensive surgical staging by the gynecological oncology multidisciplinary team were collected and the disease managed according to the Portuguese Guidelines on Gynecological Cancer reviewed in 2020. All hystologic types of EC and cases of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia were included. Previous studies demonstrated that the use of a SLN algorithm does not compromise the detection of stage IIIC disease in patients with deeply invasive endometrioid endometrial cancer, or in patients with serous and clear cell cancers, though the populations in which SLN biopsy are appropriate are still debatable21-25. In up to 35% of cases the final histopathological analysis reveals a higher grade lesion than the initial biopsy1. Women with synchronous cancer, gross metastatic disease, past history of allergy to intravenous or dye contrast and renal or hepatic insufficiency were excluded. Routine preoperative work-up included a pelvic MRI, a chest x-ray and computed tomography (CT) scan for low-risk and high-risk tumors, respectively, and blood tests including CA125 levels. Following a diagnostic laparoscopy and prior to exposure of the retroperitoneum, 1mL of ICG was injected into the superficial and deep (1cm) cervical stroma at 3 and 9 o’clock and clemastine was administered. One vial of 25 mg ICG solution was previously diluted in 10 ml of sterile water26,27. The fluorescent signal was then identified under NIR mode, and the SLNs excised and sent to frozen section analysis28. After SLN mapping patients underwent laparoscopic sentinel lymph node biopsy, total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy (PLND) and/or pelvic and para-aortic lym-phadenectomy (PPALND) were performed based on identification of tumor risk factors and clinical judgment.

Patients with grade 1 lesions confined to the inner half of the myometrium underwent a SLN biopsy only. Ultrastaging of sentinel lymph nodes was performed in all cases, according to the protocol established with Anatomic Pathology, which included assessment of serial sections distancing 250 µ from each other and immunostaining for pankeratin AE1/AE3. In laparoscopy, the devices used were spies from Karl Storz® (Karl Storz Endoskope GmbH & Co. KG, Tuttlingen).

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institution’s Ethics Committee (Centro Hospitalar Tondela-Viseu, 26th November, 2020). All patients gave their written informed consent.

Statistics

Variables derived from women’s medical records included demographic variables, body mass index, past medical and surgical history (including obstetric index and gynecological history), tumor histology, grade and stage (FIGO), imaging, surgical procedures performed, time interval from dye injection to SLN removal, total operative time, estimated blood loss, duration of hospitalization, location and number of SLNs removed, number of all nodes ressected and surgical morbidity. A minimum number of 20 patients recruited until publication was established. The authors conducted a descriptive analysis of the clinicopathologic characteristics and discuss the process of implementing a novel technique, sharing the teams’ understanding of SLN mapping with ICG and NIR fluorescence in endometrial cancer.

Results

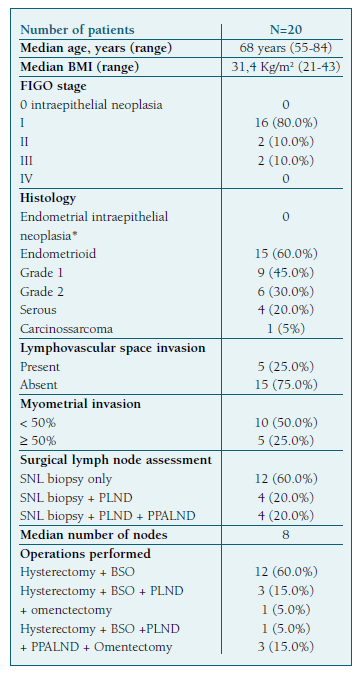

Twenty patients (n=20) were included in the study. Clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Table I.

A TLH/BSO and SLN biopsy alone was performed on 12 patients (60.0%). Out of the remaining 8 patients, half underwent a PLND and the other half a PPALND. Of the patients undergoing a full retroperitoneal staging, 3 also underwent an omentectomy and 1 an omentectomy plus resection of a mesosigmoid implant. Cervical reinjection of indocyanin green was performed in 4 cases. The median operative time was 240 minutes, the median time interval from dye injection to SLN removal was approximately 40 minutes per side, and the estimated blood loss was 150 ml.

Median operative time was lower among patients undergoing an SLN mapping only compared with patients undergoing a full lymphadenectomy (219 min vs 280 min).

One intraoperative complication occurred in a stage IIIC1 patient undergoing full retroperitoneal staging, omentectomy plus resection of a mesosigmoid implant and laparotomic left ureteric reimplantation after iatrogenic injury. No cases of ICG injection-related complications occurred.

The median number of SLNs removed per patient was 2.3 (range 1-3) and at least one SLN was detected in all patients (20/20). Sentinel lymph nodes were detected bilaterally in 14 patients (14/20; 70%) and unilaterally in 6 patients (6/20; 30%). Data on SLN mapping are summarized in Table II.

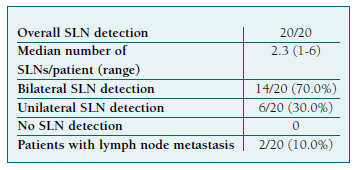

Every patient in whom at least one SLN could be identified mapped in the pelvis. In one case, 1 additional SLN was identified in the presacral region. The distribution of the SLNs is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Distribution of the sentinel lymph nodes. Obturador fossa 14.7%, external iliac artery 73.5%, common iliac artery 8.8%, aortic bifurcation 3.0%.

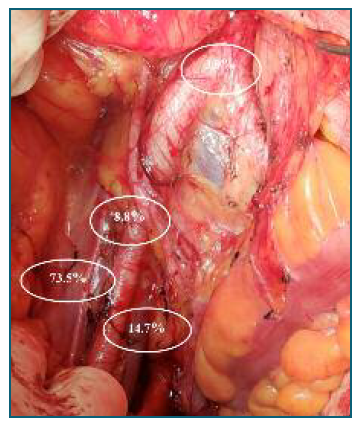

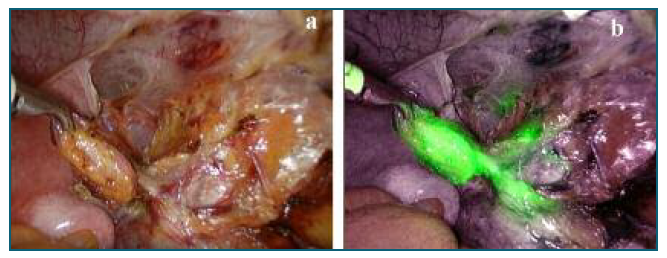

Figure 2 illustrates the appearance of the resected lymph node a) in conventional white light imaging and b) when fluorescence imaging is activated.

Figure 2 Appearance of resected right pelvic sentinel lymph node in a) conventional imaging, and b) fluorescence imaging.

Out of the 20 patients, 2 (2/20; 10%) had lymph node macrometastases. No isolated tumor cells or micrometasteses were detected on ultrastaging. One patient with serous EC presented with a conglomerate nodal mass on the left hemipelvis and a positive contralateral SLN on frozen section analysis. However, migration of ICG onto the left hemipelvis was not detected. The second patient presented with invasion of the outer half of the myometrium and 1 negative SLN was detected on the left hemipelvis. However, no SLN was identified in the right hemipelvis. On the final histopathological exam, metastases were detected in 1 out of 6 pelvic right nodes.

Out of 4 patients diagnosed with endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia on biopsy, all were diagnosed with endometrial cancer on histopathological analysis of the uterus.

Discussion

In this prospective analysis, 20 women with endometrial cancer underwent laparoscopic SLN biopsy with ICG and NIR fluorescence and comprehensive surgical staging, as part of the ongoing clinical trial at the authors’ Department on SLN biopsy in EC. In the literature, there are few and limited series using ICG as a tracer for SLN biopsy in EC. Recently, a multicenter study by Moloney K. et al. on surgical competency assessment tools for SLN dissection by minimally invasive surgery on endometrial cancer was published. There is still lack of consensus about ICG concentration and volume injected.

A lower concentration of ICG was used as injection with a lower concentration and a larger volume (< 5 mg/ml, injected volume ≥ 2ml vs ≥ 5 mg/ml, injected volume < 2 ml) provide better performance of the SLN mapping27. The use of cervical injection, in 2 quadrants (3 and 9 o’clock) or 4 quadrants (3, 6, 9 and 12 o’clock) seems to have similar detection rates27;29-31.

Of all 20 patients, 12 (12/20; 60.0%) had a TLH/BSO and SLN biopsy alone and the remaining 8 patients underwent full retroperitoneal staging (8/20; 40.0%). The median number of SLNs removed per patient was 2.3, similarly to the number reported in previous studies26. At least 1 SLN was detected in all patients (20/20; 100%), bilaterally in 14 patients (14/20; 70%) and unilaterally in 6 patients (6/20; 30%). In 1 case, a third SLN was identified amongst presacral nodes. No isolated para-aortic SLNs were detected. Persson et. all’s studies on uterine lymphatic anatomy confirmed the existence of two consistent lymphatic pathways with pelvic SLNs on women with EC: an upper paracervical pathway, with draining medial external and/or obturator lymph nodes, where 95% of SLN are to be found, and a lower paracervical pathway with draining internal iliac and/or presacral lymph nodes, where the remaining 5% of SLNs will be detected. Ipsilateral ICG reinjection in case of non-display of any lymphatic pathway and keeping lymphatic pathways intact by opening avascular planes might enhance the technical success rate.

Lymphatic drainage may be impeded by cancer cells emboli, though there is still insufficient evidence of that phenomenon in gynecological cancers (endometrial or cervical). Other factors potentially influencing lymphatic drainage are history of endometriosis or prior abdominal/pelvic surgery, pelvic irradiation and obesity32.

Our preliminary data do not allow for assessment of overall and bilateral detection rates, sensitivity or negative predictive value. In a meta-analysis by Rocha, A. et all on SLN staging, sensitivity of ICG sentinel mapping ranged from 50% to 100%. In the FIRES multicentre, prospective, cohort study of 385 patients with early stage EC of all histologies and grades, 86% of patients had successful mapping of at least one SLN, and the sensitivity to detect node-positive disease reported was 97.2% and negative predictive value 99.6%29,30. The median operative time was 240 minutes, with total SLN mapping time of approximately 40 minutes per side. These results are compatible with time intervals previously reported26,27. Median operative time was lower among patients undergoing an SLN mapping only, compared with patients undergoing a full lymphadenectomy (219 min vs 280 min). No cases of ICG injection-related complications occurred.

In 12 cases (12/20, 60%), women were submitted to adjuvant treatment, mainly external pelvic radiotherapy. In 1 case, the patients’ functional status contraindicated chemotherapy and death from disease progression occurred 6 months after surgery. In all the other 19 cases the disease has not recurred after 3 years of follow-up.

Recently published ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma state that SLN biopsy is an acceptable alternative to systematic lymphadenectomy for lymph node staging in stage I/II EC, with cervical injection of ICG being the preferred method4. National guidelines recommend the use of SLN biopsy for investigation purposes only1. Owing to the paucity of data, the decision to dissect paraaortic lymph nodes likely depends on assessment of the uterine pathology, patient comorbidities and performance status and on the presence of gross pelvic nodes, as the incidence of isolated positive paraaortic lymph nodes is very low33-35. The question remains as to whether there is a therapeutic value to completion paraaortic lymphadenectomy in the setting of pelvic nodal metastasis. Additionally, the role of completion pelvic and/or paraaortic lymphadenectomy in the setting of SLN metastasis is unknown.

Conclusions

This is the first published series of laparoscopic sentinel lymph node biopsy using ICG and NIR fluorescence in endometrial cancer, conducted in a Portuguese hospital. The Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s (SGO) and SLN Working Group consensus on SLN mapping and staging in endometrial cancer recommended completing at least 20 SLN procedures with subsequent lymphadenectomy prior to adopting an SLN algorithm, due to the absence of precise learning curve in the endometrial cancer. The clinical trial is ongoing at the authors’ Department and we hope to obtain new and improved results on this novel but promising technique.

Author contribution statement

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sara Sales, Ângela Melo, Sónia Gonçalves, Nuno Nogueira Martins, Francisco Nogueira Martins; data collection: Sara Sales, Nuno Nogueira Martins; analysis and interpretation of results: Sara Sales, Ângela Melo, Sónia Gonçalves, Nuno Nogueira Martins, Francisco Nogueira Martins; draft manuscript preparation: Sara Sales, Nuno Nogueira Martins. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.