1. Introduction

The tourism industry has become an important issue in the economic, political, social, cultural, regional and local agendas, as well as to academic research. Its multiple dimensions have been largely contributing to the enhancement of the flow of people from place(s) to place(s) and to the growth and development of regions and countries.

With regard to the verified volume of transactions, the paper entitled "Making Tourism Sustainable: a guide for policymakers", prepared by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP, 2005), shows that tourism grew by 25% between 1995 and 2005, promoting the creation of around 74 million direct jobs and 215 million indirect. Looking at the data from 2005, tourism industry's share was around US $ 4.218 billion of the world gross product and 12% of the international exports.

Meanwhile, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), in its "International Tourism Highlights" report, indicated that destinations registered 1.1 billion international arrivals in the first nine months of 2019, about 43 million more tourists than the same period in 2018 (UNWTO, 2019).

More and more people are willing to travel to places and destinations to get in contact with and experience different cultures and customs (De Bruin and Jelinčić, 2016). Related to this, concerns have emerged regarding predatory and destructive tourism practices, which require the tourist industry to follow sustainable paths (Seabra, 2001; Soares, 2011). On the other hand, this route demands the industry to act as a lever of development at regional and local levels (Buarque, 1999; Cunha and Cunha, 2005).

These concerns are present when investigating scientific production on tourism (cultural, creative, local and communitarian) and regionalisation and decentralisation processes aiming to develop public policies to promote tourism. Once committed to promoting development, the associated strategies should not be guided only by purposes of economic growth, but also by the linkage between the economic, the social and the sustainable.

Based on this perspective, we set out to look at the relationship between creative tourism and development, as interrelated fields of knowledge that we can find in the literature. This link is of overwhelming importance to plan, support and executedevelopment policies that can contribute to boost the value of local things.

In this context, we understand "thing" as a reference to a certain object or good, material or immaterial, which concedes meaning, or meanings, to people's ways of living, communities and territories. This can be translated into diverse types of heritage (e.g., historic buildings, castles, churches, ruins), natural resources (e.g., beaches, waterfalls, rivers, caves, mountains, ecological parks), knowledge (e.g., cheese, food, drinks, plants and herbs expertise), practices (e.g., planting and cultivation techniques, artisan practices, artefacts) and customs (e.g., popular festivals, lifestyle, traditions, behaviours).

These two fields (creative tourism and development), distinct and convergent, strengthen possibilities of autonomy, emancipation, experience, solidarity, tradition and income generation for places outside the ones supplying conventional tourism. Tourist practices that take on creative features bring with them the potential to overcome the reductions which limit culture to its economic value or to the act of consuming products.

After what has been said, the theme to be discussed in this paper is creative tourism and its relations with development, specifically local development. In particular, the aim of the research is to identify how international literature on the issue looks at the connection between creative tourism and local development, using as research method a survey on the documents (e.g., papers, book-chapters, books and theses) available in the main international scientific databases.

We assume that this relationship may be essential to support local development in the case of cities and communities that are not considered as touristic, but which have potential within creative tourism parameters.

Besides the Introduction and the Final Remarks, this paper is structured in three sections: i) theoretical discussion on creative tourism and development, considering the connections between the economic, social and sustainable components; ii) systematisation of the methodological procedures, including the presentation of the instruments, resources, strategies and criteria for data collection; iii) presentation and discussion of the results obtained.

2. Conceptual framework

Tourism, either domestic or international, has been experiencing a growing trend in a significant number of regions in the world related to the amount of visitors and revenues generated (UNWTO, 2019), further accentuating its impact on different destinations. This growth tendency resulted from and has contributed to favour accelerated transformations in the infrastructures of transport and communication since the transition from the Fordist regulation model to the flexible accumulation one.

According to Harvey (1990), the current regulatory model is based on the flexibility of working processes, labour markets,

products and consumption patterns. Transformations bring about consequences, both on what concerns time and space, as well as the need to find answers and solutions associated with fast changes in consumption patterns.

Changes in time and space impact social, cultural, political and economic practices and have consequences on the tourist activities supplied. Having been expressing itself by a growing demand for a set of more diversified everyday activities, tourism keeps being associated to the needs and desires of travellers (rest, leisure, knowledge, contemplation, experiences, perceptions), who are in fact looking for amusement and satisfaction (Grotsch, 2006; Som et al., 2014; Vareiro, Cadima Ribeiro and Remoaldo, 2018; Ramos, Rosová and Campos; 2019). Keeping this in mind, leisure and consumption have to be essential dimensions in the agenda of tourist destinations, which must be able to structure products that meet the expectations and consumption needs of their visitors.

2.1 Tourism and development: the local and creativity

In what regards creative tourism, one of its main features is the participation of local communities (Richards and Raymond, 2000; Arandjelovic, 2015). In this dynamic, the possibility of creating "synergies" between the local community, tourists and other tourist stakeholders should be central in the formulation of policies aiming to provide quality of life to populations and maintaining the authenticity of the places (Yázigi, 2001; Richards and Wilson, 2007).

It is a fact that the creative tourism market segment has been growing worldwide, as well as having impact on the economic, social, cultural and environmental components of the territories, both at regional and local levels. This evolution, and keeping in mind the concept of creative tourism, has been supported by pillars that emphasise the valorisation of culture, experience, co-creation, community participation, and the relationship between tourists and the general reality of the destinations (Richards and Raymond, 2000; Richards and Wilson, 2007; De Bruin and Jelinčić, 2016; Remoaldo et al., 2019). Therefore, the notion of "local" is embedded in the materialisation of creative tourism.

From this point of view, before proceeding to the systematisation of the literature on "creative tourism and local development", it is necessary to announce the methodological path followed. The aim is to make the relationships between creative tourism and development (sustainable, regional and local), and also to show the different research fields which have been contributing to the academic production on the subject. Three stages form this route: i) creative tourism and its areas of interest; ii) development and its scope; and iii) the links between creative tourism and local development.

With regard to creative tourism, Richards and Wilson (2008), following Richards and Raymond (2000), claim that it deals with a new form of providing tourists with a differentiated tourist experience. It is based on the idea of not reducing culture to the act of consuming products, but being able to promote creative economy, generate emancipation processes, autonomies, experiences, solidarity, preserve traditions, and generate income in places outside the conventional tourism routes.

Within the previously stated parameters, cultural goods and services are not conventional goods, like in traditional tourism formats, as they incorporate meanings, histories, the identity of places and co-creation, and also expressions that are based on the relationship between tourist and local communities (Richards and Wilson, 2007). It is claimed that, by relying on the transformation of the local reality based on culture, creativity, community participation and co-creation, and byassuming a decisive role in the elaboration and implementation of cultural policies, they (creative tourism destinations) attract a new tourist profile: the creative tourist (Richards, 2011; De Bruin and Jelinčić, 2016).

Creative tourism is not the same as cultural tourism, in a general sense. The latter can translate into widespread demand, together with the standardisation of tourist products, a kind of "serial reproduction" (Richards, 2019), without the concern of preserving the singularity and the material and immaterial attributes of places. Therefore, creativity plays a central role in creative tourism offer, in which the tourist experience relies on the uniqueness and material and immaterial attributes of the places and communities that are visited.

In what concerns the scope, development is characterised as a concept which goes beyond economic growth. It includes elements that intertwine the social and the economic (Simões Lopes, 1979; Sachs, 2008; Veiga, 2008). It embraces a certain kind of "triplet of interests" which establishes a link with other ways of looking to what is the wellbeing of a community. It presupposes stages that go beyond the organisational patterns of society, established by the metric of the modern western industrial rationality, and it favours experiences outside this quadrant of social, cultural, political, symbolic, imaginary and, above all, economic relations. Sousa Santos (2000) called the rationality based on economic growth a "waste of experience".

Creative tourism presents demographic, geographic, territorial, identitary, racial, social, moral, symbolic, material and immaterial configurations and specificities, which are linked to diversity, biodiversity, ethics and bioethics, all of which enable the constitution of a set of "creative" activities and social actors tourist, tourism, industry, community, agents of development with potential to promote platforms that can translate into economic, social and sustainable development.

The ordinary concept of "development" brings with it the idea of "evolutionary" stages within the organisational patterns of a society established by the metrics of modern industrial and western rationality, and was originally centred on the dynamics of economy and, so, on economic growth.

In an etymological attempt to demonstrate how much the term development is committed to an idealised path of evolution and progressive level, Pimenta (2014, p. 49) defines it as an "Act or effect of developing. [...]. Gradual transition from a lower level to a higher one. [...] Extension, amplitude [...]". For this author (Pimenta, 2014), this approach leads to the feeling that progress provides symmetry and a relationship between the concepts of economic growth and development.

In the last decades, this interpretation has been questioned, and the need to look for new metrics to understand what development should be was emphasised. The social, the sustainable, the regional and the local, as well as issues that go beyond economic growth, have gained strength.

From a historical point of view, the concept of development is linked to the ones of wealth, wellbeing, growth and economic health of nations and, in certain cases, to the death of the weakest (Adelman, 1961; Furtado, 1974; Schumpeter, 1934; Smith, 1982). Western society is characterised by a context of multiplication of exclusions, converging on an economic system which, in order to remain dynamic and competitive, must reduce costs and increase labour productivity (Godelier, 1996). As a result of such philosophy, the economy becomes the main cause for exclusion of individuals and does not exclude them only from the economy. It excludes or threatens to exclude them also from society in the long run (Godelier, 1996).

In a way, creative tourism brings an approach to the tourism industry that presupposes benefiting people, communities, collective and cooperative work (Richards and Raymond, 2000; Richards and Wilson, 2007; De Bruin and Jelinčić, 2016; Remoaldo et al., 2019), and this movement requires making practical choices, in addition to putting in place concepts of economic growth that manage to minimise competition and the consequences of a culture centred on individualisation. However, vigilance and constant care should be promoted in order to prevent devaluations of the styles and ways of life and the preservation of the traditional social relations of the places.

In what regards the relationship between creative tourism and local development, through creative tourism the focus is on other forms of organisation, in confrontation with the socio- cultural consequences of the development of individualistic models and consumption-oriented practices. This stems from the idea of promoting a tourist offer grounded on collective, community, sustainable practices based on cooperation, trust, security, tradition, belonging, co-participation and co-creation.

Creative tourism is based on structural elements that differentiate it from conventional tourism. Instead, traditional tourism is developed following a set of values and practices that keep tourists in a logic of repetition, usually close to the things they know and experience in their places of origin. In the book "Caosmosis", Guattari (1992) presents tourism as a "false nomadism", whose function is to leave us in the same place. The mentioned author claims that we are before a paradox, where everything looks like it is changing (music, advertising slogans, tourists, industrial branches) and, at the same time, everything seems to be petrified, remaining in place. Many of the differences between things get blurred, as it happens between men and women. Within those standardised spaces, everything has become interchangeable, equivalent. Tourists make almost immobile trips, being deposited in the same types of aeroplane cabins, buses, hotel rooms and seeing landscapes they have already seen a hundred times on their television screens or in tourism promotional flyers and brochures. Thus, subjectivity risks ceasing to exist (Guattari, 1992).

From what was mentioned above, we can point out that the problem is in the institutional response provided in terms of tourism policies, which have been based on the hegemonic rationale of the model. However, the literature also points to the difficulties of local communities to understand the proposals of creative tourism.

Our notion of development has an implicit relationship with sustainability at its social, economic, cultural and environmental level. This means valuing history, territories, politics and communities in their identities, in the generalised sense of these terms, which impose the establishing of symmetries, respect and vertical hierarchies in the distribution of material and immaterial resources obtained from exchanges, and respecting values, cultural patterns and interpersonal relationships.

These elements provide meaning to the dimensions of rurality, traditions and community ties that are inherent to them and are eroded by the pragmatic search of economic progress. In practice, there is the need to implement tourist practices that allow respecting the ways of life of individuals, local daily life and traditional relationships (Pimenta, 2014).

2.2 Creative Tourism and Development: a few additional considerations based on a review of literature

In what concerns creative tourism, as stated by Remoaldo et al. (2019), a worldwide consensus on the concept and its implementation has not been achieved yet. This statement was the result of a review performed on the subject based on the international creative tourism networks and platforms available. They also mention that this type of tourism aims to offer the opportunity to co-create and develop the tourist's creative potential. Co-creation and creativity are structural elements inherent to the constitution of the creative tourism "product" (Remoaldo et al., 2019).

Duxbury and Richards (2019), in their proposal of a creative tourism research agenda, recognise that this is a tourism niche that has its origins in two main assumptions: i) it is a consequence of cultural tourism development; ii) it emerges as an alternative to mass cultural tourism. These assumptions, adding to the characterisation of co-creating and the tourist's creative potential, strengthen the claim of the aforementioned authors that "Creative tourism demand is driven by travellers seeking more active and participative cultural experiences in which they can use and develop their own creativity" (Duxbury and Richards, 2019:1).

This market niche, according to Duxbury and Richards (2019), has been deepened, defined and conceptualised since the term (creative tourism) was proposed by Richards and Raymond (2000). Being centred on creativity, there are links between creative tourism, knowledge, training courses and learning experiences, which even incorporate psychological dimensions (experiences, affections, emotions, and sensations).

By presenting itself as an alternative to mass cultural tourism, creative tourism establishes a close connection with elements, aspects and values that endow it with the potential for contributing to local and regional communities transformation, according to sustainable social development models. It incorporates in its definition and practices the notions of rural, community, place, gastronomy and lifestyle. From there, it makes a strong appeal to the main features associated with local development in its different dimensions (economic, social and sustainability). Keeping these connections in mind, we may ask: how can creative tourism be intertwined with the interests of the local development knowledge research field?

As a commodity and industry, tourism is directly influenced by global technological and informational changes which impact local spaces. Within this context, creative tourism needs to detach itself from the ordinary predatory features of the tourist industry, and of other industries it relates with.

Creative tourism's proposal of breaking with the idea of predatory behaviour, ordinarily associated to the tourism industry, allows its practices and activities to strengthen the processes of preservation of heritage, history, memory and identity of places. According to Ruschmann (2001), the object of commercialisation of tourism is directly linked to preservation as, while the common industry destroys to produce, tourism must preserve to produce. The harmonisation of tourism with the environment is a structural change, a conceptual innovation envisaged to overcome a contradiction easily verified between destructive tourism and the protection of tourist resources that must be carried out to make the industry sustainable.

Creative tourism is not immune to the effects of massification due to the tendency for cultures' standardisation (Hall and Gay, 1996). Even facing this risk, there is the possibility for visitors to experience uniqueness, to live singular and individualised experiences, as well as the chance for adopting different life models. It offers experiences to tourists that go beyond the standardisation of processes, which are common in today's culture. The dictum "everything that is there, must be here" cannot perhaps be applied, because if it does, it will bring its extinction since the tourist seeks the different, the unusual.

To look for creative tourism exclusively from the "economic development" perspective, that is, without considering that it includes concerns of sustainability and social wellbeing, is to adhere to the movements of concentration, competition, exclusion, poverty and imbalance (Cunha and Cunha, 2005), since the concept assumes the need to put in place a network of agents that are part of a process of inclusion, participation, solidarity, production and competitiveness.

The concept of development which favours economic growth as an essential means of attaining progress and prosperity excludes any other possibility of social transformation. According to Pimenta (2014), this would not be a problem if the direct consequence of economic development - centred on the equation capital versus labour - did not lead to inequality, exclusion and unemployment.

In turn, social and sustainable development aims to aggregate knowledge, action, processes, people, places, artefacts, memories and ways of life. Sachs (2012) argues that sustainability must oppose the "abyssal inequality scandal", and points out the existence of a small minority who occupies the spacious and comfortable cabins on the deck of spaceship Earth, while the majority is condemned to a miserable life in small cells, having to work hard to survive.

In practice, creative tourism may not be an alternative to the hegemonic mode of production, when regarded as a product, a consumer activity or a commodity. However, it presents the possibility of reframing this logic, privileging creativity in its forms of production, placing itself far from the logic of industrial processes and the capital versus labour relationship.

The reference to tourism and development, with emphasis in creative, can highlight knowledge, practices, activities and experiences that foster new social processes and others that may shape the search for income generation under different organisational approaches. That may open the way for incorporating dimensions relevant to work, education, regional/local/rural development, sustainability and territory that go beyond and can overlap conventional tourism and traditional development practices.

Creative tourism has the possibility of assuming and structuring local socio-cultural and socio-economic dynamics. Interpreting Schiavinatto (2013), creative tourism enables development based on both material and symbolic resources, and demands the mobilisation of social actors - economic, cultural and political agents - and people, in general, to expand the field of action of the community. This way, self- determination, freedom and the role of the local in decision- making can be enhanced.

For Sousa, Oliveira and Carniello (2008), the local/regional is highlighted in the search for development, and tourism becomes an important instrument for the generation of income, employment and survival. In turn, according to Pimenta and Mello (2014), local productions are assumed to be alternatives to generate income and can directly benefit certain sectors of society. Moreover, the value of those products can be enhanced when associated with creativity, in dialogue with the local culture. The social context, the local culture and the sustainability of the productive processes provide the tourist valorisation of the place, give meaning to it, and strengthen the emphasis put on the importance of establishing a relationship between tourism and development.

The dialogue between tourism, development and creativity must be guided by five different principles: environmental, economic, social, cultural and spatial or territorial. It must also allow other factors from outside the economic universe to flourish: human capital, social capital, natural capital, symbolic capital, good governance, respect for differences and diversity, solidarity, cooperation and valorisation of the place.

This effort goes hand in hand with the understanding of the peculiarities of life, nature and people, aiming at an increase in the quality of life and wellbeing of the people, i.e., contributing to the elimination of poverty and adopting alternative practices capable of committing to the preservation of natural and cultural environments. This effort also means taking a relevant step to avoid falling into the temptation - and trap - of self- destructive competitiveness (Sachs, 2008).

3. Methods

With regard to the methodological procedures used in this investigation, we have followed the suggestions of Tranfield, Denyer and Smart (2003) regarding gathering data on intellectual production which address the issue of creative tourism and local development.

The inventory of the intellectual production is part of the integrative review approaches, which allow the inclusion of articles of different nature. The large sample, together with the multiplicity of proposals, should generate a consistent and understandable perspective of complex concepts, theories or problems (Souza, Silva and Carvalho, 2010), relevant to build a panoramic regard on the subject.

The research is justified by the exponential growth experienced in the world by the supply of creative tourism experiences (Richards, 2018), usually seen as an instrument for leveraging economic, social and sustainable development (Goodwin, 2008). This relates to creative tourism being composed of elements which establish valuations of culture, experience, co- creation, community participation and close relations between the tourist and the destination's reality.

In the integrative reading of privileged intellectual production, it is pertinent to systematise the information available on creative tourism to verify if the relationships found were in fact connected with development, since this can be considered a tourist modality that tends to oppose conventional tourism. This makes it possible to look at it as a potential way of attracting economic resources for the local and the community. Hence, the commitment to describe all the information collected on creative tourism becomes relevant.

Based on the published documents (e.g., papers, books, book- chapters and theses), the following steps were followed: i) identification of the problem; ii) setting up of a database; iii) selection of documents; iv) classification of data based on content analysis; and v) analysis and interpretation of data gathered. For this purpose, the study carried out by Richards (2018), who published a balance of the production on creative tourism on Google Scholar referring to the period between 1990 and 2015, was taken as a major reference.

Following what was decided in terms of research strategy, the next paragraphs are devoted to the presentation of the different phases of the analysis of the papers.

3.1 Step 1: Identification of the problem and selection of the research question

The subject of this article is the relationship between creative tourism and development, particularly with local development, focusing on the knowledge available in scientific literature databases. In this sense, the question we decided to enunciate was the following: what kind of relationship can we find in the literature between creative tourism and local development?

After reviewing the literature on creative tourism, namely on its characterisation and definition, which allows differentiating it from conventional or cultural tourism modalities, we have taken as descriptors to conduct the search on the databases the following keywords: "creative tourism"; “creative tourism and development”; “creative tourism and sustainable development”; “creative tourism and regional development”; and, “creative tourism and local development”.

The search was conducted in English in the following databases: Academia.edu; ACM Digital Library (Association for Computing Machinery); Cambridge Core; Econlit (American Economic Association); Google Scholar; Oxford Academic; CAPES journals (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel); Redalyc (Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal); Scielo.org (Scientific Electronic Library Online); SCOPUS; and Web of Science.

The choice of these databases was intentional, considering the general academic impact of the literature published. Those databases include the ones attaining a larger diffusion either in Latin-America - Portuguese and Spanish speaking countries - or in Europe and the world, in general.

3.2 Step 2: Establishment of inclusion and exclusion criteria

Regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we opted for the scientific papers produced in the last 10 years, from 2009 to

2019. As mentioned, the choice took as starting point Richards’ (2018) claim that 2009 had been a milestone in the multiplication of papers on creative tourism.

The research focus was scientific publication, considering that the production of materials on the subject of creative tourism materialises in products of a much-diversified nature - master dissertations, doctoral theses, projects, travel guides, technical reports, graduation monographs, documents from the Atlas network, among others. In this selection, we restricted our search to scientific publishing on journals indexed in the main scientific databases.

We established as exclusion criteria papers that, in particular, made some kind of literature review - bibliometric, integrative, state of the art, for example - on the subject or were specifically characterised by being manuals, or, even, that did not present any theoretical-empirical discussion on the construction of the creative tourism knowledge field.

The search started in September 2019 and was completed in February 2020. The term ‘creative tourism’ was used as a filter, later associated with ‘development’ and, later on, ‘regional development’, ‘local development’ and ‘sustainable development’. In this follow-up, the titles, abstracts and keywords of all papers found in the databases researched were read.

These choices aimed to identify the elements that make up the definition and the concept of creative tourism to, subsequently, establish a relationship with what is called development, and, consequently, with the issue of local development in its different aspects.

3.3 Step 3: Inventory of pre-selected and selected studies

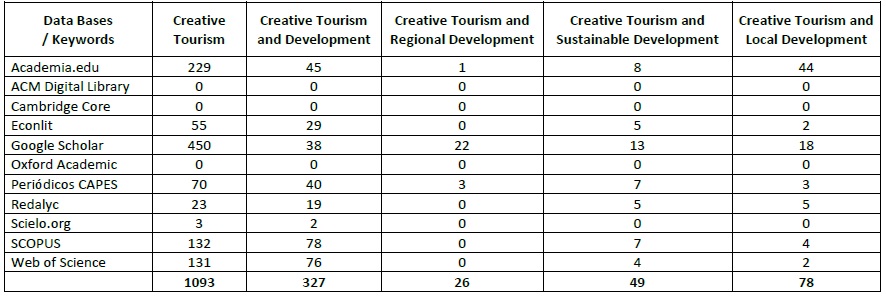

The search resulted in the identification of 1,093 articles on creative tourism and, when associated with the term development, together with its derivations, we obtained 327 papers that established a relationship between creative tourism and development, 26 between creative tourism and regional development, 49 between creative tourism and sustainable development, and 78 between creative tourism and local development, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Papers that establish a relationship between Creative Tourism and Development

Source: Authors based on the search made in scientific databases (September 2019 - February 2020).

Some papers were found repeated in one or two databases, due to the fact that the indexing of journals in different databases is not uncommon. This required extra care in terms of systematisation and choices. On the other hand, our concern was not an exact quantification of the scientific production, but an inventory of the papers that establish a relationship between creative tourism and local development. The latter was our research focus.

The amount of papers published is significant, which confirmed the assumption that creative tourism is a promising niche for literature reviews, updates and assessments on the evolution of the concept, especially for those who want to attain a better knowledge about this research field.

We dealt with the first selection of papers, based on the titles and keywords of all publications found on the investigated databases, using the combination between “creative tourism and development”, in a total of 327 productions. To narrow down the choices, the searches were carried out with the addition of the adjectives "regional", "sustainable" and "local" to the phrase “creative tourism and development”. The sample still resulted very large, if we added the 26 articles on “creative tourism and regional development” to the 49 on “creative tourism and sustainable development”, and the 78 on “creative tourism and local development”. In other words, we identified a total of 153 articles that had proposals linked to our research interests.

In view of the amount of papers which were pre-selected, in the second round we made use of a qualitative approach, materialised in the reading of the abstracts of the 153 papers found. Through this reading, we intended to rigorously identify the object of study, the aims, the scientific knowledge area and the relations with the regional, the local and the sustainable levels. The purpose was to clarify the concerns and theoretical- conceptual elements associated with “development”, as a scientific field of knowledge, which were evidenced.

We decided to discard the papers that made use of the terms "Regional Development", "Local Development", "Sustainable Development" or "Sustainability" as a mere discursive resource, as we envisaged to establish a link between the "Creative Tourism" research field and the theoretical-empirical arguments that would allow linking it with the debate on the development issue.

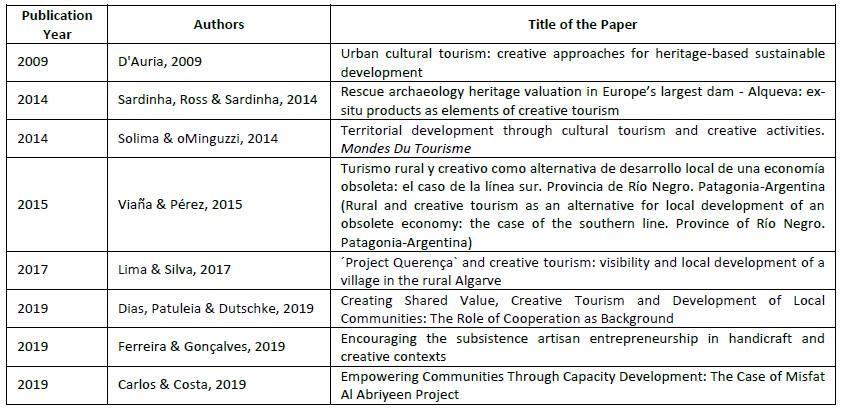

With this strategy, there was a considerable reduction in the pre-selected production, cutting down the number of papers to a total of 31, a sample that was still large. With this in mind, the following step was to perform the full reading of the articles following the aforementioned criterion, of which eight articles remained, as shown in Table 2. Here, we present the year of their publication, the authors and titles of the papers.

Table 2 Papers analysed

Source: Authors based on the search made in scientific databases (September 2019 - February 2020).

In the section Discussion and Results, we will present the characterisation of the papers collected and the relationship between creative tourism and development - regional and sustainable - they establish, making room to approach the local development issues.

We would like to emphasise that there are several papers in the databases that make use of the term development and that overlaps with the ones of sustainable, regional and local, which were discarded because, substantively, they did not establish links with the proposed field of knowledge. Therefore, the investigation was limited to surveying the publications that had, in fact, the subject defined as approach.

3.4 Step 4: Categorisation of the selected papers

From the inventory made, we detected the existence of several publications in the databases which dealt with the subject of creative tourism and appealed to the concept or emphasized concerns on development, approaching it from a sustainable, regional or local perspective, but doing so as a mere discursive resource, to highlight the importance of the creative tourism segment, as well as to differentiate it from conventional tourism.

In order to clarify the relationship between creative tourism and local development, and to point out the main features addressed by this field of knowledge, three paths were undertaken: i) inquiring on the meaning of creative tourism, according to the definitions, concepts and arguments that the diverse authors make use of; ii) analysing the concerns shown on the issue of development and their interfaces with the concepts of sustainable, regional and local development; iii) identifying the existence or not of a relationship between creative tourism and the multilevel dimensions of local development.

3.5 Step 5: Analysis and interpretation of results

According to the mentioned research strategy, from the selected papers, we were able to design a roadmap of the meanings of the term "creative tourism" and its relationship with "development", "sustainable development", "regional development" and "local development", within the following identification scripts:

The construction of a definition of what creative tourism is and its implications, considering the words that make up this concept;

Inventory of the words used and the set of links established between creative tourism and development, without losing sight of the intellectual production of the specific scientific knowledge field;

Highlighting the ideas that make it possible to group and classify the intentions of the analysed papers;

Visualising the possible unity of ideas and definitions between creative tourism and development.

From the selected material, we could identify the scientific production available on creative tourism, as well as point out its relationship with what is characterised as being development. In other words, from the inventory made, we could conclude on the existence of a plurality of meanings on what is assumed to be development and sustainability, taken together or not. This allowed us to map and evaluate the existing intellectual production in the investigated databases, knowledge that we believe to be useful as a starting point for future research on the several fronts that combine creative tourism and regional/ local/sustainable development.

4. Results and discussion

In the systematisation of papers on creative tourism (pre- selection and selection phase), we found that its guiding definition of the field was proposed by Richards and Raymond (2000). These authors define creative tourism as the kind of tourism that offers visitors the opportunity to develop their creative potential through active participation in learning experiences characteristic of the destination where they are held. The arguments of those authors (Richards and Raymond, 2000) point to the constitution of a thematic field resulting from tourist experiences organised in a few regions of Europe in the late 1990s.

Creative tourism provides the opportunity for personal creative development and involvement between tourists and hosts in a co-creation relationship, and the realisation of creative activities in the destination. These elements are a central part of the theoretical foundation of most of the papers available or definitions presented.

As our readings on creative tourism deepened, a few doubts tended to arise, namely: what is the difference between creative tourism and creative tourist? Who are the cultural creative agents and how are they formed in practical terms? Are cultural creative agents built in or are they an integral part of the local culture? In what perspective do these activities impact the territory at local level?

These doubts deserve clarification, answers, definitions and conceptualisations on the part of the researchers who deal with the issue. In this regard, through the research strategy we adopted, we want to contribute to the opening of other paths on the way of approaching the relationship between creative tourism and local development.

In terms of results and its discussion, we made the systematisation of data based on three categories: i) the meaning of creative tourism, that is, definitions, concepts and arguments that the authors make use of; ii) the field of knowledge concern on the issue of socio-economic development and its interfaces with the concepts of sustainable, regional and local; iii) the relations established (or not) between creative tourism and local development and their several features.

4.1. Creative tourism: arguments, definitions and concepts

In the databases searched, 1093 papers on creative tourism published between 2009 and 2019 were identified. This is an expressive number, which represents the concern of the Universities and development agents in the creation of a conceptual (definitions, concepts, arguments, data and information) and structural framework (political, economic, social and cultural fronts for formatting the activity) required to put in place a set of practices necessary for the development of tourism activity.

In a first moment of the investigation, we carefully analysed how the papers produced on the field of creative tourism had formulated arguments, foundations and definitions. This was done in the predisposition to map the definition of creative tourism, and then, in a second moment, to establish its relationship with development and the derived expression at local level.

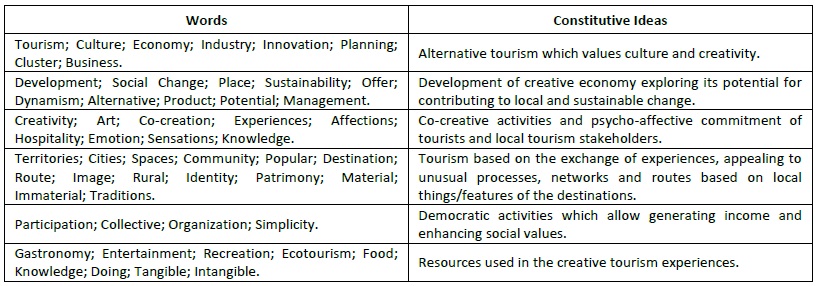

We have prepared a table (Table 3) to show what the field understands by creative tourism and, for that purpose, we have considered the two following aspects: i) the words used to devise the meaning of the concept; and ii) the visualisation of the unity of the constitutive ideas of the issue.

Table 3 Constitutive Words and Ideas Used in the Definition of Creative Tourism

Source: Authors based on the search made in scientific databases (September 2019 - February 2020).

This Table (Table 3) allows the visualisation of what is meant by creative tourism and its derivations. It also allows to verify that, in its accreditation process, countless words and ideas are used. That favours the connection of the “creative” or “creativity” concepts with the ones of economy, tourist, tourism industry, city, community, culture, space, of to do and to know.

The intersection of the words that form the concept reveals the intentionality of knowledge production, its choices and significance. Creative tourism presents itself as a “niche market”, an alternative to traditional cultural tourism. In its underlying values (prerogatives implied or implicit in the proposition of the “product market”), we have a glimpse of the starting principles: co-creation, participation, experience, perceptions, sensations, sustainability. These elements, which form the definition of what creative tourism should be, establish its potential to support a local development strategy and the need of conducting its governance at local level.

From the premise of Foucault (1971), we can understand that the values that shape the intellectual production on creative tourism attribute meanings to the pretensions of the activity's agenda and, together, the words constitute ideas. Intermediated by a discourse of order, these combine the unity and origin of statements, pointing to a focus: what one should understand by creative tourism.

Creative tourism, in its turn, when presenting itself as a tourism alternative that values the sustainability of the place, also commits itself to preserve handicrafts, artisans, knowledge, crafts, artefacts, arts, artists, cuisine (gastronomy), traditions contained in popular practices and activities, rurality and communities. As a whole, the stated values configure what we could call “the things of the place”.

Creative tourism, regarded as an alternative along the lines set out, potentially drives material and immaterial cultural features of the places to support configurations of development that go beyond economic growth, on a sustainable, regional and local basis. From the outset, this implies a strong relationship between creative tourism and development.

4.2 Creative Tourism and Development: interfaces of sustainable, regional and local conceptions

In the association of the term creative tourism with the one of development, we found that the papers produced did not fall within the scientific field of development. The words make sense and have meaning in the field of creative tourism, but they do not adhere to the theoretical-conceptual concerns present in the development debate, as well as to their economic, social and sustainable fronts.

From a total of 1093 papers found in the databases on creative tourism, 327 dealt with the issue of creative tourism and development. After deepening the search focused on the intersections between creative tourism and sustainable, regional or local development, the number of papers remained long: 26 papers for “creative tourism and regional development”; 49 for “creative tourism and sustainable development”; and 78 for “creative tourism and local development”.

We concluded that the concepts were used mainly as a discursive resource and, if the meaning of the words used in these papers was to be taken into account, they would be added to the definition of creative tourism, but disconnected from the representations inherent to development. Bearing this in mind, the next path we took was to review the links between creative tourism and sustainable development and/or regional development and/or local development, taking as a reference the object of research and the use of the word development, based on the title, keywords and content described in the abstract.

Through this research strategy, the number of papers dropped to 31. After reading the full papers, we narrowed the selection down to eight and, with the intention of specifying the object of study, the aims, the area of knowledge and the relationship with sustainable, regional and local, we found that it was not clear, or explicit, the link between creative tourism and the theoretical-empirical arguments that would allow endorsing a strategy in the field of development. This happens even when the words "Regional Development", "Local Development" and "Sustainable Development" are used.

As mentioned, the papers selected in the filtering process were analysed. Besides reading the title, abstract and keywords, the full texts were read aiming to identify the direct relationship between the field of knowledge of creative tourism and the one of development, that is, our aim was to identify a zone of intersection between the economic, the social and the sustainable, materialised in the elements and values that give shape to the local. The clearest result found allows us to conclude that the authors tended to look to creative tourism as a contributor to destinations development, taking in its various senses, but were not able to overcome the “belief” of the territorial impact of tourism on regional or local economic growth. There is, recurrently, a strong link between the use of the word development and the process of building in the tourist product to be provided.

As a result of this, there is no consistent and rigorous relationship between creative tourism and development, that is, a link based on a dialogue within the epistemological field of development or that envisaged placing itself in an interdisciplinary area, which allows looking at these subjects together. The exposed argument becomes evident when the ideas are grouped to classify the aims and intentions of the analysed products. Then, it is clear that there is unity in the definition of creative tourism, but there is no deepening, densification, conceptual or empirical reflections that take on development as a central issue in the papers reviewed. We also found that the word (development) is used in a generic way, as well as in generalisations regarding the impacts of creative tourism on income distribution, local culture, capitalisation of resources, social structure and environment.

4.3 The relationship (or not) of creative tourism with local development

The eight papers chosen to be analysed deeper show adherence to what constitutes creative tourism, strengthened by the set of arguments, theories and definitions present in the texts. From their full reading and the context investigated, we concluded that there is little empirical basis, field research, numbers and data that portray the concrete reality, and that can refute or ratify the claims on the effective contribution of creative tourism to development, in what regards the local and place.

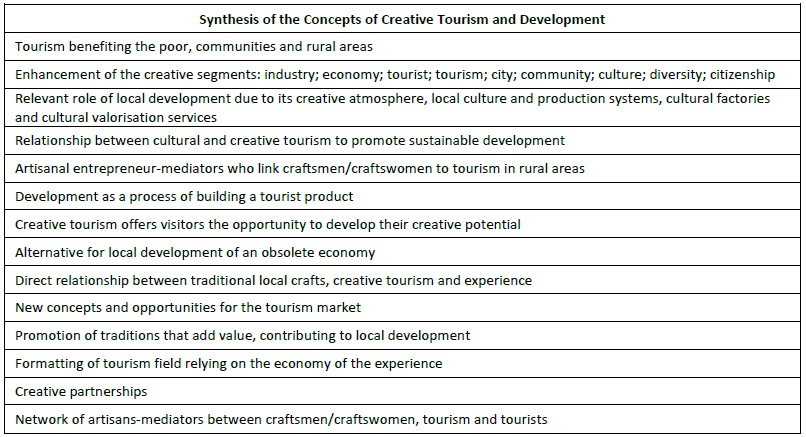

The central issue of the papers is limited to proposals on the development of the creative tourism product, including the hypotheses that intertwine the subjects of sustainability and impact at local level. As seen in Table 4, the concepts that refer to the relationship between creative tourism and development indicate a set of implications that demonstrate the existence of an “area of interest”, but this area is not in the theoretical field of development and/or sustainability, even if the authors and the field work they have performed are affiliated to economy or regional development.

Table 4 Concepts of Creative Tourism and Development

Source: Authors based on the search made in scientific databases (September 2019 - February 2020).

The studies we have been referring to point to the existence of lines of interest which join creative tourism and development. In this context, they do not concern a field of knowledge integrating

the issues related to development and, as a result, they make a generic use of the terms development, sustainability, economic impact, empowerment, local and regional.

In the scope of creative tourism, reference is made to development in the sense of a process of building a product (Nunes and Sousa, 2019), and statements on the links of creative tourism to the territory, the cohesion of the territory, competitiveness, and the potential networks of agents, economic and cultural singularities (material and immaterial) are enounced. In this context, public policies on development are invoked. These policies are supposed to intervene through culture and tourism, creating a set of normative resources that allow enhancing the economic exploitation of affections, co-creative experiences and the creativity present in the destinations.

In this sense, those claims are elements that foster development processes. The questions that arise are the following: what volume of economic resources does creative tourism generate for communities? What are its concrete and effective impacts at local level? How is material and immaterial, tangible and intangible culture incorporated? Who benefits from creative tourism?

The answers are still open in what regards the intersection between creative tourism and development’s fields of knowledge. The investigated articles do not provide such answers, but they vocalise the arguments, concepts and strategies used in the intellectual production concerning creative tourism.

The papers of Goodwin (2008), Richards (2018), Santagata and Bertacchini (2011), Solima and Minguzzi (2014), Lima and Silva (2017), Dias, Patuleia and Dutschke (2019), and Bezerra and Correia (2019), to mention just a few, bring within them the “belief” that creative tourism experiences have the potential to promote development, combined with sustainability, namely for the demands at local level, that is, for local communities, rural areas and spaces considered as not being viable for the implementation of conventional tourism.

Viaña and Pérez (2015), when investigating rural creative tourism as an option for local development, claim that it is an alternative for generating economic resources for these places, but that it requires a strong organisation and the supply of high- quality products and services. This way, Solima and Minguzzi (2014) reinforce the view that scientific knowledge on creative tourism should support regional development initiatives based on proposals of policies related to tourist destinations.

Activities, cities, places and communities which want to adopt this type of tourism need to foster a tourism culture focused on the experience of offering co-creating things, on creativity, and on committing themselves to preserve the local and community lifestyle (D 'Auria, 2009; Dias, Ross and Loureiro, 2014). The added value should result from the specific attributes of the place and from creativity, which, for Ferreira, Sousa and Gonçalves (2019) imply an incentive to what they called “subsistence craft entrepreneurship”.

Within the scope of choices and options “on” and “through” creative tourism, the production of tourism policies is welcomed. However, the chance for “success” of these possibilities is in the community, in the place and in everyday relationships, as pointed out by Flores and Costa (2019), so that the empowerment of communities is inscribed on the path to follow.

The mentioned dimension also applies to creative tourism because, in its essence, the concern is with the place, communities, the countryside, traditions, preservation, but it focuses on the performance capacities of these places, people and things because tourism is driven by creativity experiences (Lima and Silva, 2017). We could say that it is recognised as a resource able to boost and stimulate local growth and development associated with different groups. These are assumed to be “devoted” to live their daily concrete life, and the tourist is the one who must have eyes to admire the new and the unusual.

However, what is claimed does not elucidate what will be regional, local and sustainable development, as the word is mainly used as a linguistic resource that, naturally, correlates with creative tourism from the beginning, due to the definition used of the “product”. In particular, two dimensions summarise the analysed papers:

The concepts are not made available as a category of analysis (creative tourism and development), and understood in their implementation through consistent data, although creative tourism is directly linked to the preservation of nature, culture, history, scenery and traditions, as factors that allow competitiveness and development for the community;

Development is not treated as a central element to understand and measure the socio-economic and socio- organisational impacts of the cultural activities of the destination. It is also not, in equal measure, used to describe the role of the actors and the structure of the destination (political, social, cultural, symbolic, identitary), since it is placed within the production scope or the conditions that generate or not the capacities to foster a creative atmosphere.

In general, the eight articles analysed in greater depth, each with its perspective and interests, reinforce the importance of intellectual research on creative tourism and point out the relevance of analytical and policy investigations, along the following lines:

valorisation of the “best” experiences in which tourists can co-create and actively participate in the things related to the destination;

(re) discoveries at local level, in the sense of elaborating policies for the preservation of know-how, material and immaterial heritage and allowing the community to have decision power on the economic path to follow;

incentives available to enhance the creativity of people, places and tourists in line with the demands they face within tourism industry;

to go beyond the idea that creative tourism is a mere tradable, consumable and profitable commodity. The tourist must feel that he/she is part of the place and the things he/she has the opportunity to experience.

The analysed production cannot be portrayed as a representation of all the scientific production about the relationship between creative tourism and development. However, it should be considered a fragment made available in the academic databases, which opens doors for future investigation that can surpass the accreditation of a tourism product, the idea of an alternative tourist potential, and of the empowerment of communities and places.

5. Final remarks

Culture and creative tourism have the potential to act as promoting tools of regional, local and sustainable development. They carry with them a set of elements within the scope of “creativity” that can and should be explored.

When it comes to the relationship between creative tourism and local development, we do not deny the importance of creative tourism as a potential development instrument. Nevertheless, looking to the scientific production available in the main scientific databases, this issue does not go beyond the effort to consolidate a specific tourist product.

From the research we conducted on the subject, we believe that these relationships give creative tourism a promising and significant path in studies which aim to approach the general problematic of development while showing concerns with the regional, the local, the social, the economic or the sustainable.

The links between creative tourism and development raised by the authors reviewed deserve to gain density (from the point of view of concepts, data, pillars and conceptions of development) for the effective demonstration of their various impacts, that is, economic, social, cultural, and environmental. In general, when focused on characterising the impact of development, the papers mentioned do not demonstrate their symmetrical and horizontal character regarding the role of the community, tradition and rurality, as announced in the definition of creative tourism.

With regard to the scientific field of development, in the analysis undertaken we found that the papers lack precision and deepening of the empirical arguments which assess, study and prove the effective impact of creative tourism on the community and the place. They are also not rigorous in the claims that creative tourism promotes transformations, nor do they justify the claim that this type of tourism does not bring drastic changes on local reality, of productive and societal order.

The reflection made raises a question: what is the concrete impact of creative tourism on local or regional development? The hypothesis is that, on the one hand, development agents, both due to the dynamics of local authorities and those of the market, value and give importance to this alternative tourism model assuming it confers a leading role to the local community, autonomy, co-creation and exchange of experiences with the visitors. On the other hand, they are still “tied” to or “reproduce” the capitalist economic system managerial and organisational patterns.

For this reason, and due to the interrelation between creative tourism and development, we see here a promising research field, whose investment should be made to support public policies on sustainable regional and local development and, above all, to foster economic relations that surpass the structures of power, exclusion and “empty consumption” of two precious goods: tourism and culture.

The epistemological surveillance that is required on this path uses the methodological tools that "capture" the dynamics of the regional, local and sustainable, that is, the dimensions of development, without incorporating the interferences that conventional tourism causes in cities, places and spaces.

Within this promising framework, it is pertinent to elaborate other epistemological paths for conducting the reflection on creative tourism and development, in order to find innovative strategies to endorse development. These, whether assuming qualitative or quantitative formats, must gather the appropriate empirical robustness to avoid configuring exploitation and subordination of the “strong” by the “weak”.

In this path, and according to the results attained, future research on the relationship between development and creative tourism should deepen the following issues: i) evaluation of the effective impacts of creative tourism on job and income generation; ii) assessment of creative tourism projects implemented that can be looked as instruments of local and regional socio-cultural and environmental preservation; iii) survey of the transformations promoted on tourists sites based on the criteria defined in the creative tourism concept; iv) inquiry on the use and application of resources raised by creative tourism activities; v) approach to the levels of protagonism of the communities involved in creative tourism activities.

As mentioned in the closing paragraph of Results and Discussion, the results we obtained cannot be taken as a final portrait of all scientific production on the relationship between creative tourism and development, even if they are based on the literature available in the main academic databases. Besides the possibility of the existence of papers and other sort of publications not inserted in those databases, the research strategy followed, even if considered to be logical, is not a guarantee that we were able to capture all relevant publications on the issue we chose to survey.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out with the support of the CREATOUR Project (Project no. 16437), financed by the Joint Activities Program (PAC) of Portugal 2020, through COMPETE 2020, POR Lisboa, POR Algarve and FCT (Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology) . It also benefited from the support of FAPEMIG - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado de Minas Gerais, Brazil (Edital PPM/2016) -, in the aim of the project ´Observatory of Development and Culture in the South of Minas Gerais` (Observatório de Desenvolvimento e Cultura no Sul de Minas Gerais).