Introduction

Digital communication has become essential in the marketing strategies of companies worldwide (Rodgers & Thorson, 2017). In line with this trend, social networks have grown considerably as communication channels that can influence consumer behaviour (Bang & Lee, 2016; Knoll, 2016; Lee & Hong, 2016). Digital influencers have emerged as new opinion leaders in these digital channels. They are ordinary people who, based on the content they share, eventually amass a large number of followers and become recognised as an authority on a particular subject (Lou & Yuan, 2019).

Digital influencers have been an increasingly sought-after strategy by brands (Sudha & Sheena, 2017). Currently, 80% of marketers consider the use of digital influencers an effective strategy, stating that the Return on Investment (ROI) of influencer marketing is similar to or higher than that of other marketing channels (Geyser, 2021).

The topic of social networks, influencers, and their content has attracted the attention of researchers, with several studies appearing in this field. Some studies focus on the impact of paid content (Evans et al., 2017), others on the feelings that the content published on social networks triggers among their followers (Pittman & Reich, 2016), and others on the motivations for using social networks (Sheldon & Bryant, 2016). Some still seek to understand the content characteristics that generate more significant interaction with followers (Casaló et al., 2017), while others address the type of digital influencers in marketing strategies (De Veirman, Cauberghe, & Hudders, 2017). Finally, the study by Casaló et al. (2020) seeks to understand how influencers become opinion leaders.

Although the existing studies, in particular that of Casaló et al. (2020), seek to identify the antecedents and consequences of opinion leaders, they use very general samples of respondents and do not focus on the most relevant generation of consumers (Generation Y), they focus on the characteristics of the content, neglecting the characteristics of the influencer, and do not assess the impact on the attitude towards the brand. Although trust has been recognised as relevant in the influence process, it has not been analysed. However, it has been suggested that it is relevant (Thakur et al., 2016) and should be included in future research (Casaló et al., 2020).

This paper builds on Casaló's research (2017, 2020) with the aim of understanding the impact of content and digital influencer characteristics on their ability to persuade Generation Y. As determinants, we analyse the influencer's characteristics, the content they share, attitudes towards the brand, and consumers' purchase intentions. Influencer characteristics and content are fundamental to influencing someone (Casaló et al., 2020) and, consequently, to attitudes towards the brand and purchase intention.

Earlier research has been carried out across populations and all generations, but our research focuses specifically on the part of the population that will dominate the world's major economies. In the U.S., for example, Generation Y is estimated to be around 75 million strong (Fry, 2020). Generations are distinguished by factors related to age range, shared experiences, significant social events and occurrences, thoughts, and behaviours (Sessa et al., 2007). Generation Y, or Millennials, represents individuals born between 1981 and 2001 (Cox et al., 2019) dependent on technological resources (Bencsik et al., 2016). According to Zavattaro and Brainard (2019), this generation is interested in content posted on networks (Werenowska & Rzepka, 2020). They use social media to express their feelings and develop authentic relationships and emotional connections, possess strong digital skills, high degree of permanent connectivity, and search for outstanding experiences and altruistic behaviours (Veiga et al., 2017). Generation Y is pragmatic when it comes to evaluating comments and discerning when it comes to choosing products (Dabija, Bejan, & Tipi, 2018). This study adopts a quantitative methodology with data collected through an online questionnaire and applies to Generation Y individuals who follow at least one digital influencer.

The paper is structured in seven sections. The introduction is followed by a theoretical review of the main concepts and the formulation of the hypotheses. Section three presents the research model and the methodological options. Sections four and five present and discuss the results. The final sections (six and seven) present the conclusion, contributions, implications, limitations, and further research.

2. Conceptual Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Digital Influencers

The term' Digital Influencer', which is now recognised as a professional occupation, gained popularity in 2015, before which only 'bloggers' or 'YouTubers' had been heard of (Karhawi, 2017). However, 'Digital Influencer' is a new name for an old activity. For many years, influencers from a wide range of fields have been supported by teams that provide the necessary support for their dissemination and integration into professional challenges, such as lucrative branding contracts (Ronnie & Brown, 2021). For decades, brands have sought to increase their influence through the celebrity endorsement process (McCracken, 1989).

There are several definitions of the term 'Digital Influencer'. A digital influencer is an individual who attracts an online audience -beyond their friends and family -and to whom they communicate through the digital content they produce, thereby influencing the behaviour, opinion, and values of others (Lampeitl & Åberg, 2017). This practice allows companies to engage in collaborative processes and share information between digital influencers and their followers (Hajli, Shanmugam, Papagiannidis, Zahay, & Richard, 2017).

Karhawi (2017) defines digital influencers as a specific type of internet celebrity. This media presence attracts a large audience and can turn their online visibility into a lucrative digital career. According to Lincoln (2016), these individuals are multimedia content creators on digital platforms or social media who express their experiences and opinions about brands, thereby influencing the mindsets and decisions of others. As stated by Loubach et al. (2019), it is clear that digital influencers can influence the purchase decision process of the products and services they promote on social media, which can mobilise opinions and generate reactions in online communities (Lincoln, 2016). They are individuals who attract an online audience beyond their friends and family, communicate through digital content and can influence their followers' behaviour, opinions and values (Lampeitl & Åberg, 2017).

An aspect that also attracts consumers and emphasises this type of online celebrity is the credibility and trustworthiness they convey (Lou & Yuan, 2019). These celebrities produce content that gives them a reputation in the digital environment, making them a necessary and trustworthy information filter (Karhawi, 2017).

It is necessary to recognise the different types of digital influencers to make the right choice according to the organisation's objectives (Terra, 2017). If the digital influencer is identified as a credible source, their content will significantly impact their followers' admiration for a particular brand (Hughes et al., 2019). It is, therefore, essential for brands to choose the most appropriate digital influencer to communicate and promote their brand.

In terms of classification, digital influencers can be micro, macro, and mega influencers (Bullock, 2018) or, according to Santos (2017), micro-influencers, macro-influencers, and celebrities, varying in their credibility, reach, and ability to interact with their followers (Gretzel, 2017; Rios, 2017; Scott, 2014).

Managers need to understand each type of customer and adapt creative strategies that affect the quality of advertising (Ashley & Tuten, 2015). Therefore, the choice of digital influencer must consequently consider that the image of the product/service will be associated with the professional. For this reason, it is necessary to study the reputation of the digital influencer before entering into a partnership (Berlitz & Rauber, 2019).

According to Lakhani (2008), persuasion is a type of human communication designed to influence decisions and actions involving the persuader and the persuadee. Persuasion occurs through various oral or written messages to change knowledge, beliefs, and interests (Murphy et al., 2003). Based on the Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty, 2018), social media users are attracted by published content and can follow two different paths: the central and the peripheral path. Influencers are evaluated by the content produced when followers actively engage in persuasion through the central path (Lee & Theokary, 2021). Through the peripheral path, followers evaluate specific characteristics of the influencer (Lee & Theokary, 2021). Therefore, it makes sense to understand better the content and characteristics of the influencer who best fulfils their role as an influencer.

2.2. Content characteristics

Content marketing is a type of marketing used by businesses and digital influencers. It provides valuable and consistent content to inform, educate or entertain customers and prospective customers to increase interaction and sales (Al Khasawneh et al., 2021). According to (Holliman & Rowley, 2014), this type of marketing is already considered the most important tool in the digital world. For Alagöz and Ekici (2016), content is a generic term that can be presented in different formats, such as written blog posts, website information, magazines, newsletters, e-books, reports, and social media posts (Alagöz & Ekici, 2016; Wall & Spinuzzi, 2018). Originality, uniqueness, quantity and perceived quality are the characteristics of content that users consider the most important in stimulating interaction and the willingness of users to follow the advice from digital influencers (Casaló et al., 2020).

Originality

Originality refers to the degree of novelty and differentiation of the content, which should be perceived as unique, unconventional, and innovative (Casaló et al., 2020). The originality of the content influences the intention of the interaction between influencers and users. The greater the surprise or interest, the more likely users are to comment or share (Peters et al., 2009). When influencers post original and creative content, they are more successful and can increase their follower count (Mendola, 2014), thereby attracting a larger audience (Casaló et al., 2017). Given the impact of content originality on influencer leadership (Casaló et al., 2017) with a focus on Generation Y, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H1: The originality of the influencer's content positively affects their ability to persuade.

Uniqueness

Content uniqueness is based on the ability of the content to present itself as unique and different and to stand out for its differences (Casaló et al., 2020). Content must be seen as specific, unique, and different to be admired by users (Gentina et al., 2016) as weel as appealing (Barbosa et al., 2023). Casaló et al. (2020) suggest that the more creative, innovative, unique, and special the content, the more persuasive it will be. Therefore, it is assumed that this is also the case for the generation under study:

H2: The uniqueness of the influencer's content positively affects their persuasiveness.

Quality

Content quality refers to the aesthetic quality of the image, the writing skills, the type of language and visual style used, and the use of logos - elements that affect the success of the influencer and influence their followers (Casaló et al., 2020). According to Pappas et al. (2017), quality is an important characteristic of the persuasion process. This characteristic also considers aspects like the comprehensiveness of the content (Lu et al., 2013), linguistic diversity, assertiveness, and affect (Huffaker, 2010). Leal et al. (2014) confirm that content quality builds a persuasive reputation. Likewise, Pappas et al. (2017) consider the quality of the content to be a very important characteristic in the persuasion process of digital influencers. In this context, and taking into account Generation Y, the following hypothesis has been proposed:

H3: The quality of the influencer's content positively affects their ability to persuade

Quantity

The amount of content the influencer publishes represents the digital influencer's activity and the number of publications and responses (Casaló et al., 2020). It refers to the volume of the influencer's communication. A high level of communication and activity (number of posts and replies) is associated with the ability to influence online (Huffaker, 2010). Therefore, the number of times a brand or influencer posts content on social media determines the number of times a consumer is influenced by that brand/influencer (Casaló et al., 2020). This characteristic is important because the active participation of the influencer is essential to building their reputation in the community and is an important factor in their ability to persuade (Leal et al., 2014). The volume of communication and the high level of communication activity are associated with the ability to influence others (Huffaker, 2010). In this sense, the following hypothesis is formulated for generations Y:

H4: The amount of the influencer's content positively affects their ability to persuade.

2.3. Characteristics of the Digital Influencer

Due to the relevance of digital influencers in social media research, several studies have investigated the characteristics they need to have in order to achieve the desired effect (Thakur et al., 2016). Two of these key characteristics are trust and the ability to interact.

Trust

Since the 1950s, source credibility models have been based on social psychology research, emphasising the expertise and trustworthiness of the source (McCracken, 1989). Sources that demonstrate expertise and trustworthiness are considered credible and, therefore, persuasive (McCracken, 1989).

Trust is an important characteristic when it comes to determining how much influence digital influencers wield. This characteristic is a fundamental pillar in relationship building, especially when an influencer aims to achieve reputation and closeness with their followers (Uzunoğlu & Kip, 2014). Trust can be seen as a solution to the risk of uncertainty that consumers feel when buying online or following a digital influencer's recommendation (Devens, 2017). Building a relationship of trust is important because it can lead followers to adopt certain behaviours and naturally accept the recommendations of the digital influencers (Liu et al., 2015). This relationship is built through consistent communication through specialised content that shows they know about a particular product. This sense of wisdom and expertise reinforces digital influencers' trust in their followers (Liu et al., 2015). Schimmelpfennig and Hunt (2020) argue that the credibility of the source depends on the trustworthiness of the expert, and the more trust the expert inspires, the more persuasive they will be. In this context, and concerning Generation Y, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H5: Trust affects the persuasiveness of the influencer.

Interaction

This feature means that the audience interacts with the influencer, which is important if the influencer wants to be successful and recognised by their followers. Interaction is vital to developing online communities (Blazevic et al., 2014). Every influencer has a strategy to promote this (Glucksman, 2017) and encourage consumers to interact via social media (Tsimonis & Dimitriadis, 2014). Content developed by influencers conveys information and allows their followers to engage in conversations with influencers and other users (Smith et al., 2012). Content sharing allows consumers to express their opinions and experiences, encouraging online interaction (Akar & Dalgic, 2018). Interactive web advertising features help increase consumer satisfaction and experience, contribute to positive attitudes towards advertising (Bevan-Dye, 2013) and help consumers express their preferences (Chu & Kim, 2011). In this sense, consumer interactions motivate other consumers to comment on or share their experiences (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). This is because the more positive comments consumers observe about a product, the more likely they are to buy that product or service (de Vries et al., 2012). According to (Farivar et al., 2021), the greater the followers' perception of interactivity with the influencer, the greater the influence on the influencer's positive recommendation. This will significantly boost the influencer's persuasive power and, inevitably, the consumers' purchase intention. Labrecque (2014) also demonstrated that the digital influencer's ability to interact positively affects the influencer's persuasiveness. Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated for the generation under study:

H6: Interaction ability affects the influencer's persuasiveness.

2.4. The effects of persuasive influence

Choosing the right brand spokesperson is crucial. Several studies have attempted to identify the right influencer, highlighting the impact of celebrity characteristics on persuasion (Veirman et al., 2017). Consumers rarely have complete information about whether a product meets their needs, so they base their evaluation and decision on assumptions. As a result, consumers typically prefer to buy products with high brand awareness (Macdonald & Sharp, 2000). However, brand awareness increases when an influencer endorses a product (Veirman et al., 2017). In this respect, a study by Hwang and Zhang (2018) found that the relationship between digital celebrities and their followers positively impacts brand attitudes and even purchase intentions. Additionally, authors such as Schouten et al. (2020) found that digital influencers have a greater influence on consumers, regarding purchase behaviour and attitudes towards the brand, because they have greater perceived credibility, trust and similarity, as well as a greater social presence, which gives them a greater degree of influence.

Brand attitude

Attitudes are general evaluations based on beliefs or affective reactions (Brakus et al., 2009). In the context of branding, attitudes are characterised by psychological tendencies to evaluate objects in terms of preferences (Silveira et al., 2011). Brand attitude consists of a consumer's overall brand evaluation (Bruhn et al., 2012). The attitude towards the brand is crucial in building strong brand/consumer relationships (Sheth & Kim, 2017). According to (Pedron et al., 2015), by maintaining regular contact with their followers, influencers maintain the relevance of the brand/company in the market by increasing consumer awareness and perception of a particular brand. In the same vein, Hernando et al. (2018) confirm that persuasiveness is one of the most important characteristics of the digital influencer for the subsequent behavioural change and conclude that persuasive communication can lead to positive attitudes and, consequently, positive behaviours towards the brand. This conclusion is important because positive attitudes lead consumers to make positive comments and recommend the brand to others (Casaló et al., 2020). In this sense, it is assumed that influencers play an important role in shaping the attitudes of Generation Y towards the brand. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7: The influencer's persuasiveness positively affects the consumer's attitude towards the brand.

Purchase Intention

The concept of purchase intention has been widely studied, and different authors have proposed several definitions. For Vahdati and Mousavi Nejad (2016), purchase intention is considered one of the most important concepts in marketing. Purchase intention can be defined as a judgement made by the consumer in a subjective way, which influences the overall evaluation of the state of a product or service (Balakrishnan et al., 2014).

Santiago et al. (2020) mention that purchase intention refers to a specific moment or situation in which the consumer is willing to purchase the product. Purchase intention refers to the consumer's perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours (Mirabi et al., 2015), to the consumer's evaluation of a brand, product, or service, and reflects the consumer's willingness to make a future purchase or repurchase (Balakrishnan et al., 2014).

Influencer marketing, which brands promote through the collaboration of influencers, plays a crucial role in consumer purchasing behaviour. Given that influencer marketing aims to increase brand awareness among their followers, thereby contributing to increased sales (Lou & Yuan, 2019), the following research hypothesis is proposed for Generation Y:

H8: Consumer's attitude towards the brand positively influences their purchase intention.

3. Research Model and Methodology

3.1 Research model

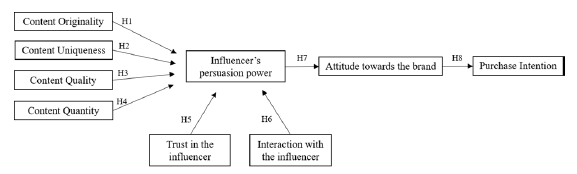

This study aims to analyse the influence of the content (originality, uniqueness, quality, and quantity) and influencer's characteristics (trust and interaction) on the ability of influencers to persuade Generation Y individuals and influence their behaviour, namely their attitude towards the brand and their purchase intention.

Accordingly, the subsequent conceptual model is proposed (Figure 1).

3.2 Data collection and sample

Before the primary survey, an online pilot survey was conducted to check the reliability of the measurement items and verify that respondents understood all the questions. No significant changes were made to the questionnaire as all respondents understood it.

Data were collected through an online survey distributed by sharing the link on social platform sites (Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram and WhatsApp). This method allows more responses to be collected quickly and effectively (Saunders et al., 2012). This method has been used in other studies on the same topic (see, for example, Chaihanchanchai et al., 2024 and Ghosh & Islam, 2023).

The study used a non-probability sampling approach. In this sense, the questionnaire was applied to a convenience sample of Generation Y individuals. This generation is of interest to the study as they are the most frequent users of social networks (Cox et al., 2019), follow influencers (Feng et al., 2021), and search for information about brands on social networks (Kemp, 2020).

The sample of this study comprises 201 participants (Table 1). The majority of respondents are female (68.16%), have a Bachelor's degree (50.25%) and have a monthly net income of less than €1,000 (51.74%). Most respondents follow the influencer on Instagram (86.57%), 7.46% of respondents on Facebook, and 3.48% on YouTube. Regarding the frequency of viewing the content posted by the influencer, 34.33% of respondents view it one to three times a week, and 34.33% view it every day. Regarding the product category associated with the brand the influencer is promoting, 26.37% of respondents said "beauty", 22.89% said "fashion", and 21.39% said "sports".

3.3 Questionnaire design

The questionnaire consisted of seven sections. The first section explained the purpose of the questionnaire and ensured that responses were anonymous. In the second section, respondents had to state their age and whether they followed one or more digital influencers on social networks. If respondents did not belong to the generation under study (Generation Y) and did not follow a digital influencer, they were directed to the last page of the questionnaire, thus ending their participation. The third section consisted of four questions. Respondents had to indicate the social network on which they viewed the influencer's content, the frequency of visits to the influencer's social network page, the product category, and the brand promoted by the influencer. The brand question was designed to help respondents answer the questions about content characteristics (originality, uniqueness, quality, and quantity), trust in the influencer, interaction with the influencer, persuasiveness of the influencer, attitude towards the brand, and purchase intention.

All items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1= "Strongly Disagree"; 5= "Strongly Agree") and were adapted from previous studies. Items related to content originality were adapted from Casaló et al. (2020) and Moldovan, Goldenberg, and Chattopadhyay (2011), and content uniqueness was measured using a scale developed by Casaló et al. (2020) and Franke and Schreier (2008). Items to measure the quantity and quality of content were adapted from Park and Lee (2009) and Casaló et al. (2020). To measure trust in the influencer, items were adapted from Teng et al. (2014) and Casaló et al. (2020). To measure interaction, the items were adapted from Godey et al. (2016), Labrecque (2014), McMillan and Hwang (2002), and Xiao, Wang, and Chan-Olmsted (2018). Finally, the items measuring influencer persuasiveness, attitude towards the brand, and purchase intention were adapted from Teng et al. (2014), Torres, Augusto, and Matos (2019), and Colliander and Dahlén (2011), respectively.

4. Results

This research used partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) with Smart PLS 3.0 to validate the measurement mode and test the hypotheses. Before testing the hypotheses, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and reliability tests were conducted on the items to confirm the validity of the measurement model. As a result, two items were dropped.

4.1 Measurement model assessment

Table 2 shows that all factor loadings have values greater than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2023), indicating that the factor accounts for sufficient variance in the items. The Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability (C.R.) values were greater than 0.70, indicating the constructs' acceptable reliability (Hair et al., 2023).Table 2 also shows the average variance extracted (AVE) values. As all values exceeded the cut-off value of 0.50, the constructs had acceptable convergent validity (Hair et al., 2023).

Table 2 Reliability and validity of measurable items

| Constructs | Cronbach's alpha | CR | AVE | Items | Mean | SD | Factor Loading |

| Content Originality | 0.920 | 0.938 | 0.716 | The contents are original. | 2.438 | 0.667 | 0.865 |

| The contents are new. | 3.786 | 1.046 | 0.858 | ||||

| The contents are unusual. | 3.692 | 1.081 | 0.742 | ||||

| The contents are innovative. | 3.179 | 1.114 | 0.876 | ||||

| The contents are sophisticated. | 3.403 | 1.084 | 0.845 | ||||

| The contents are creative. | 3.557 | 1.045 | 0.882 | ||||

| Content Uniqueness | 0.920 | 0.949 | 0.862 | The contents are unique. | 3.801 | 1.037 | 0.896 |

| The contents are special. | 3.363 | 1.116 | 0.953 | ||||

| The contents are different. | 3.418 | 1.044 | 0.936 | ||||

| Content Quality | 0.567 | 0.821 | 0.697 | The contents are appealing. | 4.274 | 0.746 | 0.861 |

| The contents present strong arguments. | 4.478 | 0.720 | 0.808 | ||||

| Content Quantity | 0.899 | 0.952 | 0.908 | The amount of content published by the influencer is very good. | 3.796 | 0.932 | 0.949 |

| The influencer publishes a lot of content. | 3.637 | 0.994 | 0.957 | ||||

| Trust in the influencer | 0.896 | 0.928 | 0.764 | I feel comfortable using products promoted by the influencer. | 4.080 | 0.922 | 0.800 |

| I have no hesitation in considering influencer suggestions. | 3.642 | 1.151 | 0.868 | ||||

| I feel safe following influencer suggestions. | 3.915 | 0.971 | 0.915 | ||||

| I trust influencer recommendations. | 3.940 | 0.976 | 0.909 | ||||

| Interaction with the influencing | 0.921 | 0.941 | 0.761 | It's easy to contact the influencer. | 3.095 | 1.430 | 0.870 |

| The influencer is willing to interact with me. | 3.139 | 1.390 | 0.915 | ||||

| The influencer interacts frequently. | 3.453 | 1.269 | 0.872 | ||||

| The influencer makes conversation between users possible. | 3.348 | 1.311 | 0.860 | ||||

| Influencer makes it easy for me to give my opinion. | 3.507 | 1.301 | 0.845 | ||||

| Influencer's persuasion power | 0.792 | 0.906 | 0.828 | I will likely accept the content published by the influencer. | 4.104 | 0.843 | 0.914 |

| I am influenced by the content published by the influencer. | 3.572 | 1.170 | 0.906 | ||||

| Attitude towards the brand | 0.931 | 0.956 | 0.879 | This brand is good. | 4.284 | 0.813 | 0.945 |

| This brand is nice. | 4.348 | 0.778 | 0.959 | ||||

| This brand is appealing. | 4.368 | 0.769 | 0.908 | ||||

| Purchase Intention | 0.923 | 0.951 | 0.865 | I will probably purchase the branded products promoted by the influencer again. | 3.940 | 1.096 | 0.937 |

| I intend to purchase the branded products promoted by the influencer. | 3.910 | 1.098 | 0.943 | ||||

| I may purchase the branded product promoted by the influencer in the future. | 3.990 | 1.056 | 0.910 |

Source: survey’s data

Correlations between the constructs and the square root of the AVE values were analysed to assess discriminant validity. If these values are higher than the first ones and the correlations between the factors do not exceed the value of 0.85 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), the discriminant validity is supported. Table 3 shows that both of these conditions are met.

Table 3 Discriminant Validity

| Attitude towards the brand | Purchase Intention | Interaction with the influencer | Content Originality | Influencer's persuasion power | Content Quantity | Content Quality | Content Uniqueness | Trust in the influencer | |

| Attitude towards the brand | 0.938 | ||||||||

| Purchase Intention | 0.691 | 0.930 | |||||||

| Interaction with the influencer | 0.264 | 0.396 | 0.873 | ||||||

| Content Originality | 0.173 | 0.214 | 0.221 | 0.846 | |||||

| Influencer's persuasion power | 0.471 | 0.630 | 0.404 | 0.263 | 0.910 | ||||

| Content Quantity | 0.209 | 0.236 | 0.194 | 0.751 | 0.292 | 0.953 | |||

| Content Quality | 0.442 | 0.496 | 0.435 | 0.363 | 0.619 | 0.383 | 0.835 | ||

| Content Uniqueness | 0.196 | 0.229 | 0.257 | 0.839 | 0.257 | 0.755 | 0.317 | 0.928 | |

| Trust in the influencer | 0.586 | 0.697 | 0.440 | 0.269 | 0.713 | 0.300 | 0.566 | 0.305 | 0.874 |

Source: survey’s data

4.2 Structural model and hypotheses testing

Regarding model fit, the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) was 0.053. Thus, an SRMR of less than 0.10 confirmed an acceptable model fit. The predictive power of the model was assessed by examining the R2 and Stone Gaesser's (Q2) values. All R2 values were greater than 0.10 (Influencer's persuasiveness: 0.579; Attitude towards the brand: 0.222; Purchase intention: 0.478), and all Q2 values were above zero (Influencer's persuasiveness: 0.548; Attitude towards the brand: 0.285; Purchase intention: 0.277), so the model has significant predictive power (Hair et al., 2023).

Table 4 shows that influencer persuasiveness is directly influenced by the content quality (β = 0.297, t = 4.034) and the trust in the influencer (β = 0.523, t = 8.418). The influencer's persuasiveness directly influences the follower's attitude towards the brand (β = 0.471, t = 7.875). Likewise, attitude towards the brand directly influences purchase intention (β = 0.691, t = 17.385) (Table 4).

Table 4 Direct effects

| Hypotheses | Supported? | β | T Statistics | P Values | |

| H1 | Content Originality -» influencer's persuasion power | No | |||

| H2 | Content Uniqueness -» influencer's persuasion power | No | |||

| H3 | Content Quality -» influencer's persuasion power | Yes | 0.297 | 4.034 | < 0.001 |

| H4 | Content Quantity -» influencer's persuasion power | No | |||

| H5 | Trust in the influencer -» influencer's persuasion power | Yes | 0.523 | 8.418 | < 0.001 |

| H6 | Interaction with the influencer -» influencer's persuasion power | No | |||

| H7 | Influencer's persuasion power -» Attitude towards the brand | Yes | 0.471 | 7.875 | < 0.001 |

| H8 | Attitude towards the brand -» Purchase Intention | Yes | 0.691 | 17.385 | < 0.001 |

Source: survey’s data

Regarding the indirect effects (Table 5), trust in the influencer indirectly increases the follower's attitude towards the brand by increasing the influencer's persuasiveness (β = 0.247, t = 5.068). Trust in the influencer also indirectly increases purchase intention by increasing the influencer's persuasiveness and the follower's attitude towards the brand (β = 0.17, t = 4.318). Similarly, influencer persuasiveness indirectly influences purchase intention through the follower's attitude towards the brand (β = 0.326, t = 6.091). Additionally, content quality indirectly influences the follower's attitude towards the brand by increasing the influencer's persuasiveness (β = 0.140, t = 3.568). Similarly, content quality indirectly influences purchase intention by increasing the influencer's persuasiveness and the follower's attitude towards the brand (β = 0.097, t = 3.348).

Table 5 Indirect Effects

| β | T Statistics | P Values | |

| Trust in the influencer -» influencer's persuasion power -» Attitude towards the brand | 0.247 | 5.068 | < 0.001 |

| Trust in the influencer -» influencer's persuasion power -» Attitude towards the brand -» Purchase Intention | 0.170 | 4.318 | < 0.001 |

| Influencer's persuasion power -» Attitude towards the brand -» Purchase Intention | 0.326 | 6.091 | < 0.001 |

| Content Quality -» influencer's persuasion power -» Attitude towards the brand | 0.140 | 3.568 | < 0.001 |

| Content Quality -» influencer's persuasion power -» Attitude towards the brand -» Purchase Intention | 0.097 | 3.348 | 0.001 |

Source: survey’s data

5. Discussion

Influencer marketing is fundamental to unlocking the potential of social networks and getting the most out of the digital world. Digital influencers develop and publish their content to attract followers. However, some content and influencer characteristics can help to increase the influencer's persuasiveness, especially for Generation Y.

Contrary to the findings of Casaló et al. (2020), content quality is the only content feature that leads to an influencer being perceived as highly persuasive by Generation Y. This may be explained by the fact that content quality is a way of reducing pre-purchase uncertainty (Pappas et al., 2017). Quality is associated with more vivid and engaging content (Casaló et al., 2020). The more understandable the content, the more likely it is to be positively evaluated (Lu et al., 2013), making the product easier to understand and enhance the influencer's reputation (Leal et al., 2014). As a result, influencers become more persuasive and can indirectly change individuals' attitudes towards the brand and purchase intentions. Aspects such as creativity and uniqueness do not seem to be important in increasing the persuasiveness of influencers when the target audience is Generation Y, as they only help to capture the audience (Casaló et al., 2017) and make the content stand out for its difference (Casaló et al., 2020; Gentina et al., 2016). Similarly, the frequency of publication does not seem to affect influencer persuasiveness, possibly because Generation Y are the most frequent users of social networks (Cox et al., 2019) and follow influencers (Feng et al., 2021). As a result, exposure to high levels of communication and activity is normal for them and does not affect their perceptions or behaviour.

Regarding influencer characteristics, our results confirm the findings of Hawkins and Saleem (2024), Lou and Yuan (2019) and McCracken (1989). For Generation Y, trust in the influencer directly affects the influencer's persuasiveness and indirectly affects attitudes towards the brand and purchase intention. The influencer's reputation as a trustworthy person who makes reliable suggestions reduces the risk of uncertainty (Devens, 2017) and facilitates the acceptance of the influencers' recommendations (Liu et al., 2015). Thus, on the one hand, the results confirm that trust in the influencer is a crucial antecedent of the influencer's persuasiveness and people's attitudes and behaviours towards the product or brand endorsed by the influencer. This finding also complements previous studies highlighting the importance of influencer-promoted brand trust for purchase intention (Chaihanchanchai, 2024). Surprisingly, and contrary to the findings of Farivar et al. (2021) and Labrecque (2014), influencer interactivity does not affect the influencer's persuasiveness. This may indicate that the influencer's ability to interact or encourage interaction with Generation Y needs to be improved to become more influential. According to Blazevic et al. (2014), influencer interaction should foster a sense of community. Therefore, to increase influencer persuasiveness, influencers need to publish content that allows their followers to engage in conversations with the influencer and other users (Smith et al., 2012).

It also confirms the positive relationship between the influencer's persuasiveness and the follower's attitude towards the brand. The results align with previous studies that highlight the impact of a strong attitude towards a brand on the ability of Generation Y consumers to consider the brand as a purchase option (Pandey & Srivastava, 2016; Priester et al., 2004). Similarly, the positive impact of brand attitude on purchase intention supports the findings of Casaló et al. (2020), who suggest that positive behaviour increases the consumer's intention to follow the published advice and buy the product. Discovering how influencers can determine purchase intention continues to motivate researchers. Recent studies have identified influencer popularity (Putri & Putra, 2024) and commitment to the influencer and platform (Zhao & Wagner, 2023), among other things, as strong determinants of purchase intention.

6. Conclusion, theoretical contribution and managerial implications

This study provides a deeper understanding of influencer persuasion on Generation Y by identifying the critical characteristics of the content and the influencer, subsequently, follower behaviour (attitude towards the promoted brand and purchase intention).

Concerning content characteristics, quality is the only characteristic that affects the influencer's persuasiveness. The findings confirm that appealing content based on solid arguments strongly impacts the influencer's ability to persuade Generation Y individuals. Similarly, trust in the influencer is critical to the influencer's persuasive power. The influencer must, therefore, behave in a way that reassures their followers so that they trust their recommendations and decide to buy the product.

Theoretically, this study presents an improved model of the one proposed by Casaló et al. (2020). At the same time, it considers the effects of content characteristics and influencer-related determinants. This makes it possible to identify the direct influence of content quality and trust in the influencer as key factors in the persuasion of Generation Y individuals. The study also responds to the suggestion of Casaló et al. (2020) by expanding the antecedents of persuasive power, considering trust and including the attitude towards the brand as an antecedent of purchase intention in the analysis. This adds to the knowledge of the determinants of persuasion and explores the mediating role of attitude between influencer persuasion and purchase intention. Contrary to previous studies, the results also suggest that content originality, uniqueness of content, and influencer interactivity do not influence Generation Y behaviour. Additionally, this study focuses exclusively on Generation Y, an important source of current consumption, and is the first to empirically confirm the mediating role of influencer persuasiveness, a critical behavioural response in an influencer-follower relationship.

Regarding managerial implications, this study's findings suggest that influencers' persuasive power is related to their quality as content producers and their reliability. Furthermore, individuals who follow an influencer who consistently posts reliable content may develop subsequent attitudes and behaviours that can benefit companies. In this sense, companies need to consider the influencer's credibility and expertise when looking for an influencer to endorse a product or brand. For example, companies should look for cues (e.g. the number of posts saved or reposted by the followers) that indicate the satisfaction of the influencer's followers with past suggestions and recommendations from the influencer. Similarly, companies should pay attention to the quality of the message. Multimedia materials such as photos and videos must be high-quality, transparent, aesthetically pleasing, and linguistically assertive. This type of influencer stands out for his or her persuasive power and can change consumer attitudes and purchase intentions towards a product or a brand.

7. Limitations and future recommendations

As with all research, this study has some limitations that future researchers can overcome to increase the knowledge and applicability of the findings. First, the study used a convenience sample, which does not guarantee the representativeness of Generation Y as a whole or the generalisability of the results. Future research could use a large sample, which would help improve Generation Y's knowledge and the comparison between generations. The second limitation relates to the variables chosen to characterise the influencer. The study only analysed the impact of influencer interaction and influencer trust. Future studies should include other variables, such as the degree of specialisation of the influencer or the dimension of the influencer. Third, the study only focused on content developed by influencers (published posts). Future studies could explore potential differences between content shared in feeds, stories, IGTV, or reels.