During a pre-season evaluation, a newly transferred 20-year-old professional football player complained of pain and swelling of his right anterior thigh. He then recalled having a minor nonspecific injury at the same location approximately 2 months before, but that didn't stop him from keeping playing. On physical examination, the patient presented an elastic, poorly mobile and painful mass located at the proximal third of the anterior compartment of his right thigh (Figure 1). Additionally, he reported having pain with stretching of the quadriceps and with resisted extension of the right knee. On muscular strength testing, the power of the right quadriceps was markedly less compared with the left thigh.

Figure 1: Physical examination of the right thigh - visible and palpable mass over the anterior aspect of the proximal thigh

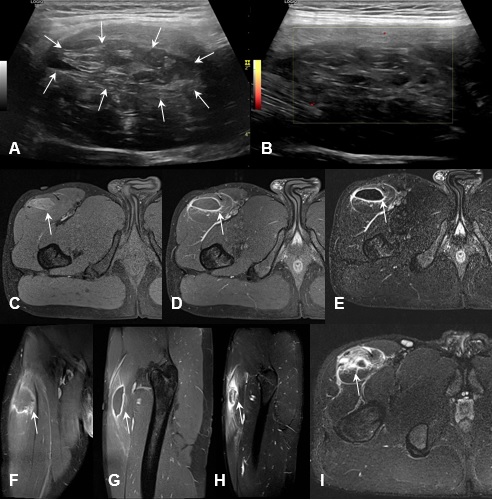

The ultrasound examination revealed a large intramuscular lesion with a reticular appearance and several organized areas (Figure 2A). The power-Doppler mode did not clearly show any vascularization within the lesion (Figure 2B). These findings suggested that the lesion could be an organized hematoma, however it was not possible to completely exclude other diagnoses like a soft-tissue tumor. Therefore, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with intravenous contrast injection was performed to further assess the lesion. The MRI confirmed the diagnosis of a subacute/chronic intramuscular hematoma of 5x6x2cm in length (Figures 2C, 2D, 2E, 2F and 2G) associated with a more recent anterolateral musculotendinous junction (MTJ) injury of the direct head in the proximal third of the rectus femoris muscle (Figure 2H and 2I).1,2,3

Figure 2: Ultrasound (GE Healthcare LOGIQ S8®; ML6-15 ultrasound transducer) examination of the right thigh showing a nonspecific intramuscular lesion with a reticular appearance and several organized areas (A) with no signal at power-Doppler mode (B); MRI (SIEMENS Healthcare Avanto 1.5T®) axial T1 FS Gd- image (C), axial T1 FS Gd+ image (D), axial subtraction image (E), coronal T1 FS Gd+ image (F) and sagittal T1 FS Gd+ image (G) of the right thigh demonstrating a subacute/chronic intramuscular hematoma with 5x6x2cm length (arrow); MRI axial T1 FS Gd+ image (H) and sagittal T1 FS Gd+ image (I) of the right tight showing an associated acute anterolateral MTJ injury of the direct head in the proximal third of the rectus femoris muscle.

A progressive muscular training program based on common strength and conditioning guidelines was designed for an estimated period of 5 weeks. Passive physiotherapy modalities were used as an adjunct in order to reduce pain and enhance the reabsorption of the hematoma. Specific training of the rectus femoris muscle incorporated a progression of isometric to concentric and eccentric load at different muscle lengths and considered the bi-articulate nature of the muscle. In the end stage of the rehabilitation process, there was a special focus on passing and kicking exercises and acceleration and deceleration in football-specific movements at different speeds.

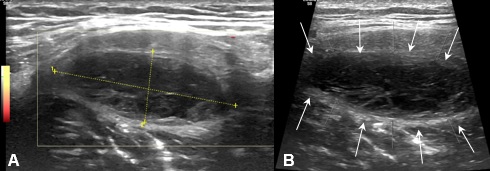

Ultrasound at two weeks of follow-up showed a reduction of echogenicity and dimensions of the hematoma (Figure 3) as well as good fibro-cicatricial evolution of the direct head MTJ injury.

Figure 3: Ultrasound (GE Healthcare LOGIQ S8®; ML6-15 ultrasound transducer) at 2 weeks of follow-up examination of the right thigh showing reduction of echogenicity and dimensions of the chronic intramuscular hematoma (A and B).

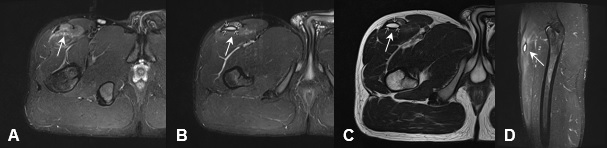

MRI at four weeks of follow-up showed a complete resolution of the direct head MTJ injury, with signs of advanced matured healing (Figure 4 - A and B), and a persistent residual intramuscular hematoma, with reduced size (2x2x1cm length) and greater organization (Figure 4 - C and D).

Figure 4: MRI axial STIR image (A) and axial T2 image (B) of the right thigh at four weeks of follow-up (SIEMENS Healthcare Avanto 1.5T®) revealing complete resolution of the direct head MTJ injury, with signs of advanced matured healing; MRI axial STIR image (C) and sagittal STIR image (D) showing persistent residual intramuscular hematoma, with reduced size (2x2x1cm length) and greater organization.

After 5 weeks follow-up, the patient had clinical and functionally fully recovered presenting complete and painless knee range of motion and no significant quadriceps weakness compared with the uninjured thigh. He was able to return to competition at least at his preinjury level, without any recurrence of symptoms.

In view of the ultrasound suspicion of an organized encysted hematoma and the absence of a clear history of trauma, it is mandatory to investigate the nature of the lesion in order to exclude neoplastic soft tissue pathology. This case also highlights the importance of the role of a properly structured and personalized conservative treatment in the recovery of these athletes and its correlation with the imaging findings.