1. Digital Political Communication

The intensive use of technology (Enli & Moe, 2013) is reshaping the public sphere (McNair, 2017) and thus the situation and structure of one of its main actors: political parties. During the last 3 decades, they have been immersed in changes driven by technological innovations (changing strategies, the growing influence of major technology companies on their actions, the emergence of new political actors and disinformation), which sometimes challenge the distribution of power and civil society. These developments have been especially significant in communication with other actors and enhanced during the pandemic (Landman & Splendore, 2020) and hold uncertain consequences for democracy (Grossman et al., 2020; Webler & Tuler, 2018).

After the first few years in which digital communication served only to publish online messages developed for offline reality, political parties soon discovered the importance of digital strategies in elections. They adopted hybrid strategies that combine old and new media in their relationship with their audiences (Chadwick, 2013). In the begin ning, overlapping content on different supports prevailed, but along the way, political parties have sought innovation in language and storytelling, an effort which has led to crossmedia narratives, transmedia and even immersive reality (García-Orosa, 2019),

The intensive use of social networks (Popa et al., 2020) supported by big data is particularly salient in election campaigns as a vehicle for communication and forecasting. The nearly uncritical use of social networks has been closely linked to one of the political parties’ main goals: engagement with their audiences, to the point that some au thors describe the current era as that of engagement (Morehouse & Saffer, 2018). Within this development, strategies that seek audience engagement stand out, sometimes as a yearning for the democratization of participation and democratic debate and, on other

occasions, simply as a new source of economic resources (García-Orosa, 2018).

Still, engagement lacks a sound theoretical model (Shen & Jiang, 2019). Definitions stemming from different areas of knowledge encompass concepts ranging from the assimilation of engagement with interactivity to those linked to psychological engagement and philosophy with the construction of behaviors with different levels of hierarchical activity ranging from passive message consumption to active two-way online conversation, participation and recommendation (Men & Tsai, 2013; Taylor & Kent, 2014). Dhanesh (2017) proposes two main conceptualizations of engagement: (a) communicative interaction manifested as clicks, likes, views, shares, comments, tweets, recommendations, and other user-generated content; and (b) dichotomous notions of engagement as control based on transactional modes of communication (public information, two-way asymmetry, organizational message dissemination) and engagement as online collaboration based on participatory modes of communication (dialogue, content co-creation, etc.).

In practice, political parties continually seek audience participation and engagement in many ways. There has been, to date, a discrepancy between the practice of engagement and the discourse surrounding it and the lack of a real incentive for citizen participation, assigning users the role of re-disseminator without insisting on their involvement or responding to their interactions (García-Orosa, 2018). However, in recent years, given the inability to control the messages users publish on social networks, parties seek cooperation in disseminating common arguments through different strategies for attracting digital volunteers alongside the traditional search for supporters, affiliates and donors. Take, for example, the Republican Party in the United States, which in 2018 began assigning online tasks to its digital activists (e.g., following the party on networks, sharing their messages on users’ profiles and helping to grow the team of digital activ ists) and conventional activists (registering new voters and hosting local party events). The Democratic Party called its supporters to action by including a directory, several causes and a guide for calling the corresponding Republican representative to convince them to vote a certain way.

At the same time, citizens were looking for new ways of participating in politics, such as the electoral groups in Spain or the media and the public sphere.

Nonetheless, parties and activists risk making digital political communication monotonous and propagandistic, with scant attention paid to the functions of civic or democratic deliberation. One of the most recent risks can be seen in the mise en scène of a new actor: digital platforms. Daniel Kreiss and Shannon C. McGregor (2018) have analyzed how Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft and Google served as advisors to political parties and shaped digital strategy, content and execution of campaign content through the development of organizational structures and staffing practices tailored to the dynamics of American politics.

Many dynamics have been identified, but most of the studies carried out thus far deal with European or American political systems. This article provides a comparative analysis of countries on three continents scarcely examined in the existing literature.

In terms of communication, the analyzed period is framed in the fourth wave of digital political communication, which is characterized by: (a) digital platforms as political actors participating in all phases of communication; (b) the intensive use of artificial intelligence and big data in all phases but especially during campaign season; (c) the consolidation of falsehood as a political strategy (among other fake news and post-truth phenomena ); (d) the combination of hyperlocal elements with supranational ones; (e) uncritical technological determinism; (f) the search for engagement with audiences and co-production processes; and (g) three trends that pose challenges for democracy: polarization of opinions, echo chambers and filter bubble (García-Orosa, 2021).

2. The Study of Political Communication in the Portuguese-Speaking World

As seen in the above-cited literature on the advancement of scientific knowledge, the Portuguese-speaking world is scarcely represented despite a significant increase in research by or about this community in recent years (Gradim et al., 2018).

This article addresses studies conducted in recent decades on the Portuguese-speaking world as a “figure of geostrategic and cultural interest and the digital media as an object of analysis” (Martins, 2015, p. 27). This article will use this perspective to analyze a major actor in the public sphere: political parties.

Portuguese has more than 250,000,000 speakers who have little sense of belonging to a community. As Martins (2016) recalled, it is a place without a voice, knowledge or recognition of similarities in this vast geographical, cultural and media space (an idea also shared by Góes & Antunes, 2017; Seixas, 2016).

These limitations are also reflected in the academic field of communication, with 25 entries in the Web of Science database, mostly from Brazil and Portugal (52% and 56%, respectively) in 2021. Furthermore, only 8% of research originates in communication sciences (compared to 26% in the humanities or 24% in linguistics). Given the small number of articles, the year over year pattern is quite irregular.

Within political communication, studies are divided into three categories: those that adopt a historical perspective (Gaudin, 2020; Izquierdo, 2017), those that perform comparative analyses between a Lusophone country and a non-Lusophone country or countries, and those that analyze the 2018 Brazilian elections focusing fundamentally on a specific technology. In the second case, it stands out García-Orosa et al. (2017) study comparing digital narratives in Portugal and other European countries, or Ituassu et al. (2019) study that compared the 2016 American elections with the 2018 Brazilian elections. Finally, in the last case, it stands out Canavilhas et al. (2019) novel study that analyzed the use of WhatsApp and demonstrated that at least 60% of messages contained wholly or partially false information. These findings corroborate the existence of a web of desinformation among WhatsApp users.

This study analyzes Portugal, Brazil, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique. In addition to allowing us to observe the transformations that technology, among other factors, triggers in political communication in seldom studied contexts, this analysis allows us to incorporate cases from continents besides Europe and the Americas.

3. Methodology

The main objective is to study the digital political communication of political parties. The main political parties with parliamentary representation in 2021 are from Portugal (Socialist Party, Social Democratic Party, Portuguese Communist Party, Left Bloc, CDS - People’s Party, People-Animals-Nature Party); Brazil (Workers’ Party, Social Liberal Party, Progressives, Brazilian Democratic Movement, Liberal Party); Cape Verde (Movement for Democracy, Independent and Democratic Cape Verdean Union, African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde), Guinea-Bissau (Movement for Democratic Alternation, Social Renewal Party, United People’s Assembly-Democratic Party of Guinea-Bissau, African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) and Mozambique (Mozambique Liberation Front, Mozambican National Resistance, Mozambique Democratic Movement).

First, we will set forth how the parties define digital communication, their strategies for using the online toolkit and the conception of their audience. We reviewed online party documents that contained their mission statements and principles and their bylaws and declarations of intent.

Lastly, we analyzed their digital strategies. The variables have been elaborated ad hoc for this research based on those used in similar studies (García-Orosa, 2018; Keller & Klinger, 2019; Landman & Splendore, 2020) to provide an in-depth analysis of digital media in political communication:

the party’s website;

the conception of digital communication and audience relations;

specific segmentation of audiences;

clear indicators of the presence of Portuguese speakers;

languages and international perspectives;

innovation in storytelling and narratives (multimedia, transmedia, crossmedia, podcasts, 360°);

fact-checking strategies;

artificial intelligence;

gamification;

social networks;

instant messaging systems;

evolving professional skillsets;

engagement with message receivers

community (belonging to a community, community restricted to party activists);

adaptation to COVID-19

4. Results and Discussion

Within the trend toward reconfiguring the public sphere through technology (McNair, 2017), the political parties analyzed herein also make extensive use of technology, especially social networks and instant messaging. The internationalization of platforms leads to homogeneity in how they are used, their implementation times and even their uptake rates. We have also observed the process of platformization in this study’s sample with the homogenization of the use of social networks and instant messaging and the influence on the praxis of political communication.

In line with previous studies, political parties mostly resort to crossmedia to disseminate their messages, that is, simultaneous dissemination across several channels, but without major adaptations in language or discourse. The parties analyzed tend to emphasize audiovisual content, mainly through YouTube. Particularly noteworthy is their reliance on audio content, both in podcasts and on platforms such as SoundCloud.

Portugal’s Social Democratic Party leverages hybrid communication by combining its digital archive of documents and the online publication of a traditional print magazine, complete with a podcast and TV channel.

Engagement, understood as a commitment between the public and the party, is the traditional link between the citizen and the party, mainly through affiliations and donations. The parties’ websites imply that to be a citizen is to fund the party or disseminate the party message, not help create content or formulate policy. Therefore, communication is largely one-way and asymmetrical (except for occasional contact through social networks and instant messaging) and does not affect the essence of the policy or the production of the message.

Consequently, the receiver, in this case, citizen, as a product of representation, an imagined entity of discourse that expresses itself through the enunciation of another discourse (Ducrot, 1980/1986), influenced by the media and public logic in the construction of its image. It reveals an audience mostly defined by political parties as recipients of messages and with a commitment uniquely defined by the continuity and fidelity of reception (newsletters) and economic contributor to the functioning of the party.

Engagement with the audience is unidirectional and is also linked to donations (Social Democrats of Portugal) or membership, examples of which abound (Portugal’s Left Bloc, CDS - People’s Party - Portugal; the Workers’ Party - Brazil). In other cases, participation is equated with attending events (People-Animals-Nature, Portugal).

Still, these parties present some peculiarities compared to parties in previous research, the first being the segmentation of message receivers. Traditional segmentation (activist or supporter as in the Portuguese Socialist Party) combines with other charac teristics depending on each area’s context and each party’s goals, but, which, in no case, are shared or common to the Portuguese-speaking area. Noteworthy segmentation includes “youth” and “women” in the Left Bloc (Portugal), Social Liberal Party (Brazil), Progressives (Brazil), and the Brazilian Democratic Movement. Furthermore, Portugal’s Left Bloc has created a 60+ group and an lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender queer and intersex group. Brazil’s Progressive Party and the Brazilian Democratic Movement create segments for the Afro-Brazilian community, and Cape Verde’s Movement for Democracy sets aside a space for the Lusophone diaspora. Nonetheless, in every case, segmenta tion exists within a traditional, unidirectional and asymmetric communication model that relies on segmentation only to offer information that could be of special interest to these groups. However, it is worth highlighting an exception: the Workers’ Party (Brazil) community that arose under the name “Center for Fighting Fake News in Your City”, in which the organization does not revolve around group identity but rather exists to address a specific issue where the political party operates. Therefore, the interaction with the user is selective.

We did not detect any significant steps towards engagement based on transactional modes of communication (instead of bidirectional asymmetry), and the parties seem to distance themselves from engagement understood as online collaboration based on participatory modes of communication, such as dialogue and co-creation of content, among others (Dhanesh 2017).

Nor did we find any signs of a search for engagement beyond the technological perspective or considered as another element of the communicative process allowing the user’s participation in all phases of the production process and influence on the content, with a few exceptions beyond the use of big data to adapt the information to users’ behavior and feelings. The search for engagement with the receiver is, above all, an important source of marketing and dissemination of information and is not very relevant to the essence and process of the parties’ communication.

The use of social networks stands out, though still without a common strategy that could prove critical for developing context-specific strategies in the coming years (Linke & Oliveira, 2015). There appears to be a need for an integrated social media strategy for distinct audiences, as has already happened successfully in other areas.

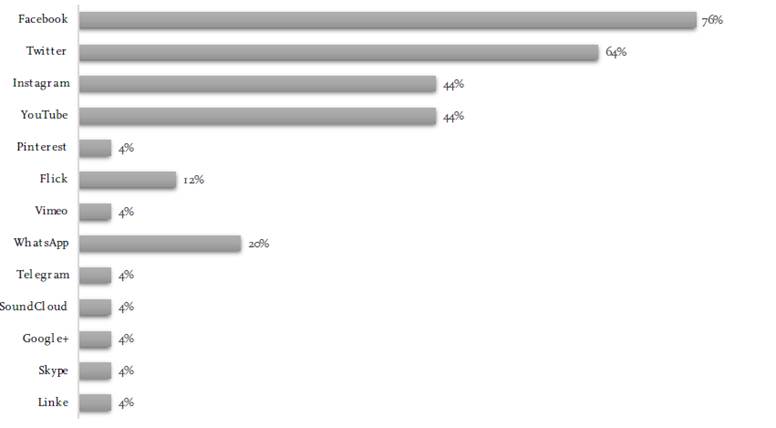

The distinguishing feature lies in instant messaging on Telegram and Skype (each used by 4% of parties) and WhatsApp (20%; Figure 1).

Figure 1 Use of instant messaging documented in previous research on the Lusophone world and podcasting

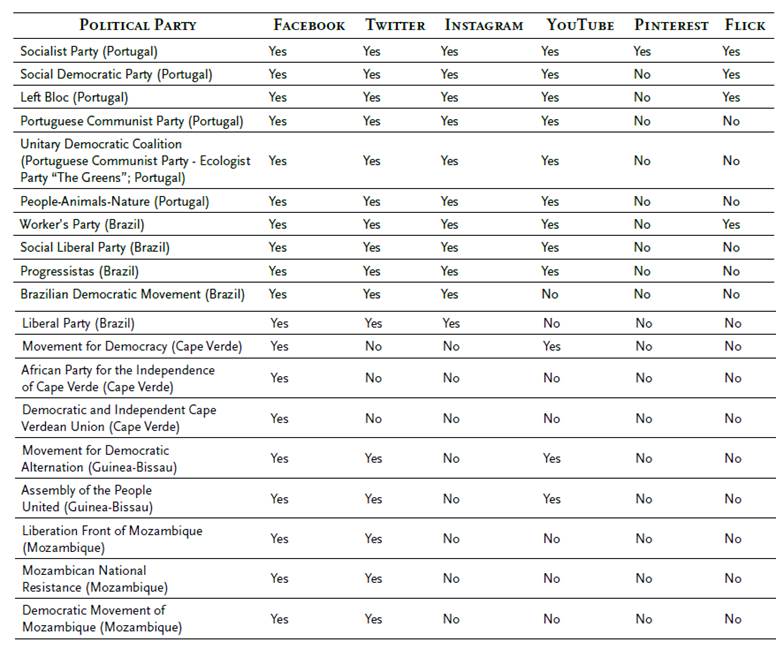

Except for the prominent use of Flick in Portugal and Instagram in Portugal and Brazil, we did not detect any country-specific trends (Table 1); rather, they mostly resemble trends observed in studies conducted in different parts of the world.

Finally, media and technical innovations are adapting to the circumstances, especially regarding mobile phones and newsletters for dissemination, while automation, immersive storytelling and transmedia strategies continue to stand out as emerging and underutilized techniques. Thus, the media consist of fundamentally asymmetric and asynchronous communication flows, with advances in storytelling and a small number of communities as in other recently studied areas (Serrano et al., 2020).

Consequently, political parties tend to dominate communicative and political action and use the public as a passive receiver, except for the option to interact through social networks and instant messaging.

In this regard, as seen in most results from political communication studies on political parties in recent years, two social networks stand out: Twitter and Facebook, used by 76% and 64% of parties, as seen in Figure 1. As was the case in other studies beyond the Lusophone world, Instagram and YouTube come in second place (44%).

Engagement takes the shape of communicative interaction, which manifests itself in clicks, likes, views, shares, comments, tweets, recommendations and other user-generated content. That is far from the notion of engagement as control based on transactional modes of communication (public information, bidirectional asymmetry, dissemination of organizational messages) or engagement as online collaboration based on participatory modes of communication (dialogue, co-creation of content, etc.), as posited by Dhanesh (2017).

Political parties link technology to their marketing strategy in specific areas of their webpages, in their founding principles and their implementation of information and communication technologies, especially on social networks.

Finally, except for the use of a common language, there is no sign of any emergence of a Lusophone community, whether in the political discourse analyzed or in the salient political communication trends, that differentiates them from others recently studied, in addition to those noted above.

5. Conclusions

This study assumes digital communication plays a significant role as a communication process and as a weathervane for political phenomena (Braga et al., 2017) during the fourth wave of digital political communication. This salient moment should also be analyzed in several contexts of the Lusophone world. Emerging trends common to other recently studied geographical areas are confirmed, such as innovation in digital storytelling, platformization and the trend towards engagement as communicative interaction. However, there are new trends towards instant messaging, podcasting, audience segmentation or engagement linked to the neutralization of fake news, some of which are summarized below.

The relationship between public actors and digital platforms, known as “platformization” (Smyrnaios & Rebillard, 2019), is increasingly close and asymmetric in political parties worldwide. Social networks are implemented homogeneously, as are their production and communication logics influence the party’s identity and its relationship with the receivers of its message. As detected in the studies conducted mainly on the United States and European political parties, Twitter and Facebook are incorporated in most parties’ websites and, therefore, in their narratives. The recent trend toward more audiovisual content is also confirmed in this study with the parties’ extensive use of Instagram and YouTube.

Underlying the homogeneous and nearly uncritical implementation of social networks is the need to reach an increasingly distant public and create long-term engage ment with them. However, the results describe communication flows that are fundamentally asymmetric and asynchronous, with advances in storytelling and a limited number of communities, as seen in other recently studied areas (Serrano et al., 2020). Engagement is the traditional link between the citizenry and political parties, manifested mainly in affiliations and donations. On their websites, the parties imply that being a citizen is to finance the party or help disseminate the party’s message, not to create content or formulate policies.

As indicated above, storytelling is becoming increasingly crossmedia, though transmedia storytelling and virtual reality in storytelling have yet to pick up steam.

The parties analyzed in this study stand out for their use of instant messaging, podcasts, audience segmentation and engagement linked to combatting fake news. This segmentation, nonetheless, is always linked to the characteristics of the message’s receiver, much less so to live chats and never to the receiver’s relationship in the communication process.

In any case, a shift towards hybrid communication strategies can be gleaned with selective interaction that neither affects the power structures of political parties nor allows citizen participation in the organization’s make-up or identity but allows only the modification imposed by technological platforms in the limitations and homogenization of the form communication can take and the content it entails.

6. Limitations

This research provides unpublished data on a previously unstudied area, and its results should be built upon with longitudinal studies in the coming years. Likewise, this work will be complemented with the analysis of other political actors, such as citizens or media outlets, and comparative studies with other linguistic communities.

texto em

texto em