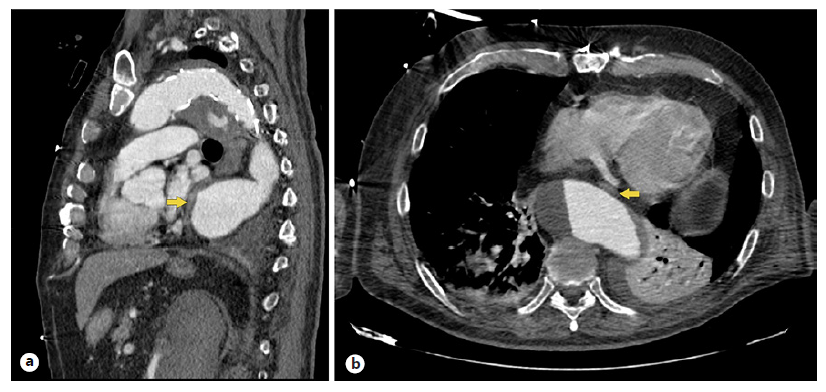

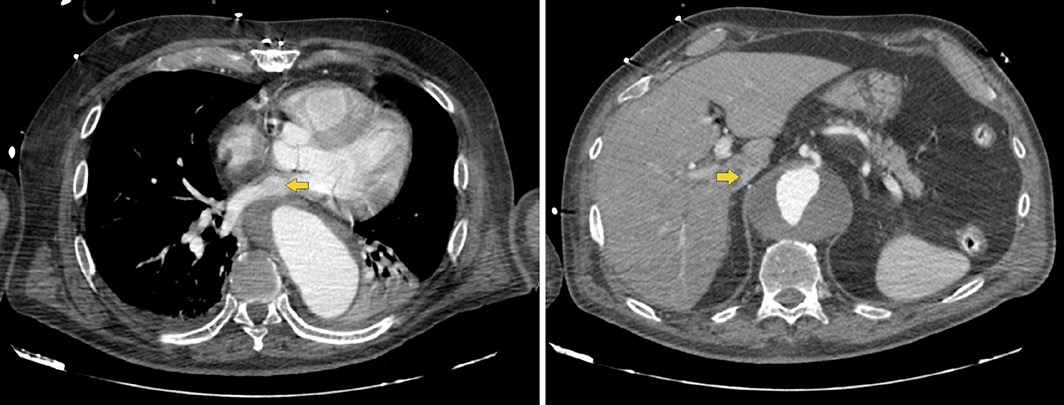

A Caucasian 75-year-old male with a history of arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, and aortic prosthesis for ascending aortic dissection in 2015 was admitted to the emergency room following an episode of syncope. There were no prodromal symptoms, lip smacking, or bladder or bowel incontinence. The patient referred a progressively worsening dysphagia, manifested by difficulty in swallowing solid food for the last 3 months, with a normal esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) performed 4 weeks prior. He presented no history of cervical pain, weight loss, dysphonia, or previous radiotherapy. The physical examination, including neurologic exam, was unrevealing. The laboratory evaluation revealed D-Dimer elevation. An arterial phase thoracic computed tomography (CT) excluded pulmonary thromboembolism but revealed an aortic aneurysm throughout all its thoracic and abdominal segments. This dilation was causing compression and displacement of the esophagus, with anterolateral deviation of the organ and a significant reduction of its lumens’ caliber in its distal third (Fig. 1). There was also an extrinsic compression of cardiovascular structures, namely the left atrium and the inferior vena cava (Fig. 2) which may explain the episode of syncope due to a compromise of the venous return. The patient was admitted for aneurysm repair surgery, which resulted in symptomatic improvement, and was then discharged.

Fig. 1 Thoracic CT showing an aortic aneurysm, reaching a maximum caliber of 62 mm. This dilation causes compression and displacement of the esophagus (yellow arrow), with anterolateral deviation of the organ and a significant reduction of its lumens’ caliber in its distal third, presenting with a maximum diameter of 4 mm in this topography. a Sagittal view. b Axial view.

Fig. 2 Thoracic CT showing external compression of cardiovascular structures (yellow arrow), namely the left atrium (a) and the inferior vena cava in its retrohepatic portion, reaching a minimum caliber of 4 mm (b).

A thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) is usually a silent disease, diagnosed as an incidental finding, which makes it difficult to assess its prevalence. Most of TAA are degenerative and associated with risk factors for atherosclerosis [1]. In case of a previous aortic dissection repair, reintervention is often required in 20-40 percent of them due to aneurysmal degeneration of the residual aorta [2], as may have happened in this patient. TAA can present initially with symptoms related to rapid expansion and compression of adjacent structures, namely dysphagia from esophageal compression, a rare phenomenon called dysphagia aortica. This term, rarely mentioned in gastroenterological textbooks, arises when the aorta pushes the esophagus anterolaterally and against the crural diaphragm [3]. The most feared complication is primary aortoesophageal fistula, typically following untreated TAA [4]. However, other causes of aortic dysphagia need to be addressed, namely aortic dissection, tortuous aorta, double aortic arch, or aortic pseudoaneurysm. Also, there are other cardiovascular anomalies that may lead to dysphagia, including abnormal right subclavian artery (dysphagia lusoria) and abnormal dilated left atrium (dysphagia megalatriensis) [5].

Considering its rarity, there is no gold standard for diagnosis and therapy. The diagnostic workup should include EGD as the first-line investigation, followed, according to clinical suspicion, by barium or videofluoroscopic swallowing study, thoracic CT, or esophageal manometry, although no single method can definitively prove the diagnosis. The treatment of dysphagia aortica depends on the severity of symptoms, comorbidities, etiology, location in the aorta, and the expected survival, which impact the choice of approach to repair (open vs. endovascular) [3]. The authors highlight dysphagia aortica as a rare clinical entity, in which lack of awareness and symptom underestimation contribute to high-risk diagnostic delay. Thoracic CT may reveal rare causes of dysphagia when first-line investigations such as EGD are inconclusive.