Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a series of changes in the world, with its direct impacts on health and mortality rates1 being followed by economic turmoil and an array of political consequences. On this latter subject, several studies examined the pandemic’s impact on political attitudes (e. g., Bol et al., 2021), turnout and voting behaviour (e. g., James and Alihodzic, 2020; Fernandez-Navia, Polo-Muro and Tercero-Lucas, 2021) or party positions and discourses (e. g., Louwerse et al., 2021; Bobba and Hubé, 2021a).

One of the earliest concerns regarding COVID-19’s political impact was that it would create the conditions for populism to grow, akin to the way the Spanish Flu contributed to creating the environment in which Nazism and Fascism flourished in Germany and Italy (Blickle, 2020; Galofré-Vilà et al., 2022). This concern is fuelled by the fact that, in the 21st century, populism is indeed seen by some, albeit not by all, as a threat to liberal democracy (for a discussion of the relationship between populism and democracy, see, Mudde, 2004 and Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017). Being a thin-centred ideology, populism may take many forms but is characterised by an understanding of society as being “ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde, 2004, p. 543). In other words, people-centrism, anti-elitism, and the goal of reinstating a certain kind of popular sovereignty are at its core.

The main reason why the pandemic could leverage populism in democratic societies is linked with the assumption that real or constructed crises represent an opportunity for populism to thrive (Laclau, 1977; Moffit, 2015), a proposition that has often been confirmed by empirical studies (e. g., Handlin, 2018, Lisi and Borghetto, 2018; Stavrakakis et al., 2018; Caiani and Graziano, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic could be an adequate environment for populism to prosper because 1) the difficulties of governments in dealing with the pandemic might increase anti-elite sentiments, and 2) even in countries with successful crisis management, specific groups of citizens may be displeased with the strategies followed. Thus, both circumstances might create a fertile ground for populism (Vieten, 2020).

Yet, the COVID-19 is a different crisis - an unforeseen and unintended event, an exogenous shock. This means that, unlike economic, migrant, or political crises, responsibility is not directly attributable to politicians, economic elites or immigrants; the usual targets of populist discourse (Bobba and Hubé, 2021a). Crises of this nature often elicit two types of effects which are, generally speaking, contrary to the expansion of populism. One of them is the rally around the flag effect - involving increased support for the incumbent (Mueller, 1970). Although typically observed at the micro level, there is evidence that a rally effect can also occur at the party level, reducing acrimony between political parties (see, regarding COVID-19, Merkley et al., 2020; Louwerse et al., 2021). This parliamentary harmony was especially felt during the first wave of the pandemic, decreasing afterwards (Merkley et al., 2020; Louwerse et al., 2021), which converges with the idea that this is a short-lived phenomenon (Johansson, Hopmann and Shehata, 2021). The other effect is the flight to safety - an increased preference for what is known, improving the prospects of mainstream/status quo parties to the detriment of anti-system or populist actors (Bisbee and Honig, 2021). In short, the actual impact of the pandemic on populism is far from easy to predict on mere theoretical grounds. The effect of the pandemic is even more uncertain as it evolved in waves, and it is plausible that the presence of populism in the political debate fluctuated depending on its severity (Meyer, 2021).

The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on populism has already been the subject of research, but the extant literature focuses almost exclusively on political parties or actors that are consensually seen as unequivocally populist (e. g., Bobba and Hubé, 2021a; Ringe, Rennó and Kaltwasser, 2023). The exception is a study on the evolution of populist discourse before and during the first stage of the pandemic focusing on all the relevant parties in Spain (Olivas Osuna and Rama, 2021). In our view, this is the most adequate way of measuring the impact of COVID-19 on populist discourse, as there is nothing that forbids parties traditionally seen as non-populist from adopting a populist discourse if they see it as fitting their short- or long-term goals. In fact, the adoption of populist discourse is not only bound to the degree by which parties ideologically embody the core ideas of populism but is also context-dependent ( Hawkins et al., 2019; De Bruycker and Rooduijn, 2021).

The present research seeks to contribute to this literature by studying the presence of populist discourse in parliamentary debates in Portugal over the first year of the pandemic. If populist discourse can be context-dependent, and contagion effects between parties can be observed (Olivas Osuna and Rama, 2021, p. 1), there is no reason why a spillover effect would not be observed on matters unrelated, or only indirectly related, to the pandemic but that, nonetheless, provide opportunities for the use populist frames. Those issues are immigration and ethnic minorities, corruption and law and order (Taggart, 2017), the political system (Palhau, Sivla and Costa, 2021), the welfare state (Enggist and Pinggera, 2022), banking and finance, and morality issues and lifestyle - all policy areas that are salient to left-wing and right-wing populist parties, respectively (e.g., Lisi and Borghetto, 2018; Hesová, 2021). Covering this variety of issues, our research aims to identify the extent to which there was an increase in the populist discourse of political parties after the COVID-19 outbreak and during the first year of the pandemic. We enrich the analysis of a general index of populism by focusing on specific components of the populist discourse (people-centrism, anti-elitism, popular sovereignty and exclusionism). Moreover, we study specific periods, since the pandemic was marked by different moments in terms of incidence of infections and, consequently, implementation of restrictive measures, and these fluctuations may have had an impact on levels of populism. Thus, we aim to shed light on the extent to which specific pandemic conditions might be associated with different patterns of adoption of populist discourse.

Portugal is an interesting case to study populism from a supply-side perspective. Until 2019, the country was an exception in Europe due to the absence of a full-fledged populist party in parliament. Granted, there were traces of populist discourse by Portuguese parties, with those with governmental experience being not at all prone to the adoption of such rhetoric (Lisi and Borghetto, 2018; Valle, 2020; Palhau, Silva and Costa, 2021), whereas left-most parties, especially in the context of the Great Recession, resorted to it comparatively more often, but objectively to a residual degree (Lisi and Borghetto, 2018). The situation changed in 2019, when the populist radical right party Chega (CH; Enough) (Mendes, 2021) elected a member of parliament.

This article is divided into five sections. Firstly, we provide an overview of the extant literature on the relationship between populism and COVID-19 and present our hypotheses. The following section describes the data used to test our expectations. We then report and discuss the findings of our analysis of the presence of populism in parliamentary speeches. The article concludes with a discussion of the main patterns identified and their consequences for the understanding of populism during severe crises provoked by external shocks.

Populism and the covid-19 pandemic crisis

The academic literature on populism has invariably defined the phenomenon in a myriad of ways, from concrete political strategy (Laclau, 2007) to ideology (Mudde, 2004) or political discourse (Moffitt, 2016). In this paper, we adopt the ideational approach to populism (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017), focusing on key dimensions of the concept such as people-centrism, anti-elitism and popular sovereignty (Manucci and Weber, 2017). The first involves claims that emphasise the virtues of the people and the close relationship between the populist and such a people. The second stresses the contrast between the corrupt elites and the virtuous people. Finally, the third is crucial for populist rhetoric as the source of political legitimacy. While not consensual, this approach has proven highly suitable for the analysis of political discourse, having been widely used in the context of the pandemic (e. g. Zulianello and Guasti, 2023).

The literature on populism during the COVID-19 pandemic has mainly focused on three specific issues: the impact of this crisis on citizen support for populist parties, the way populist governments tackled the pandemic, and the impact of the pandemic on populist discourse.

First, Bayerlein and Gyöngyösi (2020) show that, on average, popular support for populist - and non-populist - governments increased right at the beginning of the pandemic, with Jair Bolsonaro’s plummeted popularity being a notable exception to this trend. Regarding actual vote, the evidence points in a different direction. For instance, Alternative Für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany) lost 2.3 percentage points in the 2021 German federal elections, being that in western German regions, where the pandemic was more severe, its vote share was even lower (Bayerlein and Metten, 2022). Likewise, Baccini, Brodeur and Weymouth (2021) identified a negative relationship between the number of COVID-19 infections and incumbent Donald Trump’s 2020 vote share, suggesting that the rallying around the flag effect, identified by Bayerlein and Gyöngyös (2020) at the early stages of the pandemic, might not have lasted sufficiently long to be translated into votes.

Second, studies focusing on how populist governments have managed the pandemic found that, with a few exceptions (see Bayerlein and Gyöngyösi, 2020), their performance was disastrous. For instance, in Czechia and Slovakia, the technocratic populist cabinets engaged in erratic responses, disregarding formal institutions designed to deal with crises (Buštíková and Baboš, 2020). Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, USA’s Donald Trump and Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte either downplayed the pandemic’s severity or suggested unscientific and untested ways to deal with it. They communicated the measures to tackle the crisis in a spectacularised fashion and stressed a division between the people and an abstract body of dangerous others, thus embodying a sort of medical populism (Lasco, 2020). Populist executives at large tended to deny scientific evidence and blamed both victims and outsiders (McKee et al., 2021). Several populist governments implemented comparatively fewer measures to tackle COVID-19 in the first months of the pandemic (Kavakli, 2020), thus creating the conditions for the spread of the disease (Bayerlein et al., 2021). Interestingly, several of these patterns have already been observed in some countries in relation to other health-related emergencies, such as Ebola or HIV/AIDS outbreaks (Moran, 2018; Lasco and Curato, 2019).

Furthermore, while some studies show that governments featuring major populist parties were not more prone to formally weaken the parliament’s policymaking role than, for instance, single-party governments (Bolleyer and Salát, 2021), other studies find evidence of average to high risks of threat to the political systems’ checks and balances in the measures introduced by populist governments to deal with the pandemic (Bayerlein and Gyöngyösi, 2020). Ringe, Rennó and Kaltwasser (2023) also report that tactics leading to the centralisation of power were quite common amongst 29 populist parties and leaders in 22 countries during the pandemic. This panorama is in line with the understanding of populists as crisis entrepreneurs (Bobba and Hubé, 2021b) as such actors tend to be more interested in promoting crisis cycles to extract political benefits from them than in contributing to their solution (Moffitt, 2015).

In what concerns the literature on the pandemic’s impact on the degree of populist rhetoric adopted by parties, most studies published until now have focused on parties that are usually considered populist, and on how pandemic-related issues were framed. Magre, Medir and Pano (2021) found that both the radical right VOX (Latin word for Voice) and the radical left Podemos (We Can) focused on the content of their manifesto proposals, but while the former exacerbated its anti-establishment stance, via strident criticism of the Spanish government, Podemos was conditioned by its role as a member of the ruling coalition. In Italy, while Lega (League) struggled to adapt its traditional populist discourse to the pandemic emergency throughout 2020 (that is, before becoming a member of the Grand Coalition that governed Italy as of February 2021), the Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement) dropped much of its traditional, strongly populist discourse, due to its institutional responsibilities (Bertero and Seddone, 2021).

These two examples show how some populist parties - but not all of them - have apparently decided to put populism aside when framing the pandemic. In Bobba and Hubé’s (2021b) and Ringe, Rennó and Kaltwasser’s (2023) analysis, the incumbent/opposition dichotomy explains some of the differences between populist parties, with the latter being naturally more prone to both politicising the pandemic and blaming the government. Meyer (2021) further demonstrates that populist parties’ aggressiveness towards the incumbents is positively correlated with the severity by which the country was being struck by the pandemic. Also, host ideology seems to matter too, since during the first stages of the pandemic right-wing populists tended to emphasise nationalism and to stress the idea of a cleavage between the “good people” and threats coming from outside (either at the EU or from other outgroups), whereas populist left-wing parties focused more on the lack of investment in public health system due to the EU’s neoliberalism, thus stressing their anti-elite stances (Bobba and Hubé, 2021b). In short, the way in which populist parties and governments responded to the pandemic crisis was multifaceted, resisting simplification (Zulianello and Guasti, 2023).

The effects of the pandemic on populist discourse, however, go beyond the specific behaviour of full-fledged populist parties. Research focusing on non-populist parties is, nevertheless, much scarcer. Olivas Osuna and Rama’s 2021 article, covering the period between March and June 2020 in Spain, is an exception. The authors report that populist rhetoric also grew in the cases of non-populist right-wing Partido Popular (Popular Party) and populist left-wing Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (Republican Left of Catalonia), with both presenting a similar trend to that described for VOX, i. e., an increase in people-centrism and anti-elitism over time. If one excludes Ciudadanos (Citizens), the pattern is of an increase in the use of populist discourse by opposition parties and stagnation by incumbent parties, regardless of their starting point. This suggests that regardless of possible rally around the flag or fight to safety effects, populist rhetoric ended up permeating to a greater or lesser extent the majority of the Spanish political parties.

This review of the literature allows us to formalise a series of hypotheses to be tested with data from the Portuguese case. First, drawing on Osuna Olivas and Rama’s (2021), and arguments in favour of a general increase of populistdiscourse during crises (Laclau, 1977; Handlin, 2018; Stavrakakis et al., 2018; Caiani and Graziano, 2019), we expect that levels of populist discourse have tended to increase after the pandemic hit the country (Hypothesis 1). Moreover, since the severity of the pandemic seems to be related to the surge of populism (Meyer, 2021), we expect this trend to be more noticeable when the pandemic is felt more seriously; that is: during the first, second and third waves of infection (Hypothesis 1.1). These are the moments of greatest importance of the incumbent’s response, with other parties stressed to monitor the government’s performance, thus creating more opportunities to resort to a populist discourse.

Second, we hypothesise that, as in the Spanish case (Osuna Olivas and Rama, 2021), this growth in populist rhetoric will be particularly visible in terms of people-centrist and anti-elitist stances (Hypothesis 2). Moreover, based on the argument that populist rhetorical aggressiveness is linked with the severity of the pandemic (Meyer, 2021), and similarly to H1.1, we expect people-centrist and anti-elitist rhetoric to grow especially during the peaks of the pandemic when compared to post-wave periods (Hypothesis 2.1). In addition, Osuna Olivas and Rama’s findings of an increase in populist rhetoric over time, accompanied by the fact that rallying around the flag effects might not last long (Johansson, Hopmann and Shehata., 2021), lead us to expect a trend of increased focus on the aforementioned elements of populism over time (Hypothesis 2.2).

Lastly, we expect that the growth in people-centric and anti-elitist discourses will be more pronounced for parties that usually score particularly high in terms of populism, such as CH (Hypothesis 3.1); for parties that Lisi and Borghetto (2018) showed that are more prone to resort to populist discourses during a crisis, such as PCP (Partido Comunista Português, Portuguese Communist Party) and BE (Bloco de Esquerda, Left Bloc), (Hypothesis 3.2); and, as in the case of Spain (Osuna Olivas and Rama, 2021), for opposition parties rather than the incumbent (Hypothesis 3.3).

DATA

To map the populist discourse of Portuguese parties in parliament, we carried out a content analysis of the speeches made in parliamentary debates held between October 2019 and April 2021. The corpus is composed of the verbatim reports of the debates held in the Assembleia da República (Assembly of the Republic). The verbatim reports of the debates are available online.2 The parties under analysis are those with parliamentary representation in the 2019-2022 legislature: the incumbent centre-left PS (Partido Socialista, Socialist Party); the main opposition party, the centre-right PSD (Partido Social Democrata, Social Democratic Party); the radical left parties BE, PCP and PEV (Partido Ecologista “Os Verdes”, Ecologist Party “The Greens”); the centre-left animalist PAN (Pessoas-Animais-Natureza, People-Animals-Nature); the populist radical right CH; the conservative CDS-PP (CDS-Partido Popular, CDS-Popular Party); and the liberal IL (Iniciativa Liberal, Liberal Initiative).3 As previously mentioned, we selected parliamentary debates on topics that are prone to a populist approach: immigration, corruption, ethnic minorities, law and order, the political system, banking and finance, morality issues and lifestyle, and the welfare state. The units of analysis are individual paragraphs; a total of 6214 paragraphs in 59 parliamentary debates were analysed (PS = 1344; PSD = 958; BE = 870; PCP = 706; PAN = 684; CDS-PP = 645; PEV = 394; CH = 374; IL = 239).

The content analysis focused on the three basic dimensions of the ideational approach to populism (Mudde, 2004; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017): people-centrism, anti-elitism, and popular sovereignty. First, following Manucci and Weber (2017), we considered a paragraph to be people-centric when it claimed, “to be close to the people, speaks of the people as a monolithic actor with a common will, stresses the virtues of the people, or praises the positive achievements of the people” (p. 320). “The people” is operationalised in broad terms ranging from “the Portuguese”, to “the taxpayers” or more diffuse conceptions of “the majority”. Second, paragraphs were categorised as anti-elitist when they criticised elites in the name of, or in contrast to, the people. Such elites are understood by the coding process to be politicians in general, “the banks” or the wealthy. Thirdly, we identified appeals to popular sovereignty in paragraphs in which more political power is claimed for the people, in general, or in relation, to a specific policy area. A fourth component, related to the exclusion of some social groups from the category of people, was also analysed. While populism is not always exclusionist, some populists do identify and attack an outgroup - some specific segment of the population that, although not belonging to the elite, is also not seen as a part of the pure people (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007). Therefore, paragraphs in which there is a declared opposition, attack, or the establishment of a dichotomy between the pure people and an outgroup other than the elites were coded as exclusionist. Each of these concepts was operationalised as binary variables dealing with their presence in the MP’s speech.

The content analysis led to the creation of five main dependent variables: people-centrism, anti-elitism and popular sovereignty, an index of populism computed by averaging those variables,4 and a distinct measure of exclusionism which is not included in the general index of populism because this feature is not observable in all populist parties. The values for the people-centrism, anti-elitism, popular sovereignty, and exclusionism variables are the percentage of statements in which the element of populist discourse has been identified. The populism index, based on the first three indicators, also varies between 0 and 100, with higher values being representative of a greater presence of populist discourse.

The results of this empirical exercise were tested for intercoder reliability for each of the dimensions. To achieve this, coders were assigned a 10% random sample of all the paragraphs. The results of the test were at acceptable levels, thus proving that the data produced constitutes a reliable basis for our operationalisation of populism and its components.5

The test of Hypotheses 1 and 2 first implies the analysis of populist discourse in two distinct moments: before (October 2019-February 2020) and after the advent of the pandemic (from March 2020 to April 2021). The cut-off point was placed in the transition from February to March 2020 due to the confirmation of Portugal’s first COVID-19 case on 2 March.6 Then, to test Hypotheses 1.1, 2.1 and 2.2, we divided the first 13 months of the pandemic into five periods: first wave (March to May 2020), post-first wave (June to August 2020), second wave (September to December 2020), third wave (January and February 2021), and post-third wave (March and April 2021).7 Lastly, Hypotheses 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3 are tested by comparing individual parties. Despite that, our theoretical interest is chiefly the evolution of people-centrism and anti-elitism, the values for popular sovereignty and exclusionism are sometimes presented to provide readers with a complete picture.

Results

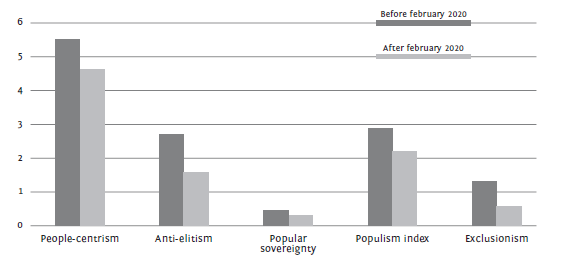

We start by comparing the incidence of populist discourse in parliamentary debates until and after February 2020. Contra expectations, a reduction in the frequency of the use of populist discourse is observable (Figure 1). This decrease is statistically significant for the index of populism [t(6212) = 2.50; p = .013] but also for specific elements, such as anti-elitism [which went from 2.7 to 1.6%; t(6212) = 2.64; p = .008] and exclusionism [decreasing from 1.3 to 0.6; t(6212) = 2.22; p = .027]. In the case of people-centrism, its shrinking from 5.5 to 4.6% was statistically nonsignificant [t(6212) = 1.30; p = .193], Appeals to popular sovereignty were already very uncommon before the pandemic, and almost vanished after March 2020, with the difference between its incidence in the two periods being nonsignificant [t(6212) = .99; p = .325]. In short, this data disconfirms our Hypotheses 1 and 2, as there is no increase either in the general levels of populism after the pandemic (but, instead, a significant decrease) nor of people-centrism (a nonsignificant decrease was instead observed) and anti-elitism (whose presence dropped significantly). A possible explanation for this result could be the prevalence of a rally around the flag effect in containing populism in Portugal over the first year of the pandemic (Silva, Costa and Moniz, 2021). In Spain, where populism grew more or less across the party system in the period after the outbreak of the pandemic (Osuna Olivas and Rama, 2021), no rally effect was registered (Belchior and Teixeira, 2023).

Figure 1 Populist discourse in parliamentary debates in Portugal before and after the onset of the pandemic crisis. Source: Authors’ own database based on the content analysis of the selected parliamentary debates.

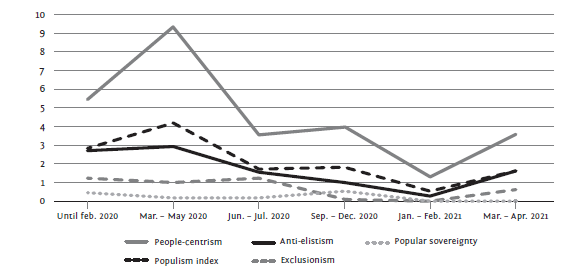

When looking at the evolution of populism between March 2020 and April 2021 (in Figure 2), it is possible to observe trends that converge with our hypotheses. As we can see, over time, the presence of populism increased in the first wave of the pandemic vis-à-vis the immediately preceding period (4.2 compared to 2.9). A decrease follows until the lowest values are reached during the third wave in the winter of 2021. After the first wave of the pandemic, the index of populism never reached the values observed either in this period or in the first months of the 2019-2022 legislature, thus only partially supporting Hypothesis 1.1; that is, solely for the first peak of the pandemic. Differences between pandemic periods are statistically significant [F(4,4605) = 14,48; p < .001] but merely in the sense that the values observed in the first wave were much higher than those of the subsequent periods, which are statistically indistinguishable (according to Scheffe’s posthoc comparisons).

Regarding people-centrism (Figure 2), the pattern is the same, with statistically significant differences only between the first wave and the following periods [F(4,4605) = 13.94; p < .001]. Instead, anti-elitism (again, Figure 2) not only did not grow during the first wave of the pandemic but decreased thereafter, being significantly less present during the second and third waves of infection [F(4,4605) = 4.15; p = .002]. In sum, there is no positive evolution in the presence of anti-elitism and people-centrism over time, which leads us to reject Hypothesis 2.2. This evidence allows us to partially confirm Hypothesis 2.1, as we note higher levels of people-centrism in the first wave than in the immediate post-wave period. However, the same is not observable in the second and third waves in comparison with the following post-wave period. Regarding popular sovereignty and exclusionism, both are residual throughout the period and there are no relevant patterns to report other than a disappearance of exclusionist frames during the second and third waves of the pandemic and of popular sovereignty from January to April 2021.

Figure 2 Populist discourse in parliamentary debates in Portugal before and in different phases of the pandemic. Source: Authors’ own database based on the content analysis of the selected parliamentary debates

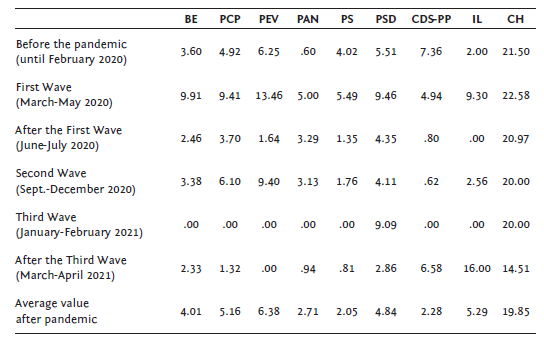

Finally, we analyse the presence of populist discourse in parliamentary debates by different political parties. Here the focus is placed on people-centrism and anti-elitism. In the case of the first (Table 1), we observe that CH, in addition to being the party that most often mobilises people-centric claims, is also characterised by a considerable degree of stability over time (with a noticeable decrease between the third wave and the succeeding period). Furthermore, only three parties do not contribute to the general peak in people-centrism in parliamentary debates during the first wave of the pandemic in comparison with the previous period: CDS-PP, CH and PS. Over time, there is a trend of stability from the populist radical right party, an erratic trend in the case of the moderate right-wing parties (PSD, IL, CDS-PP) and left-wing PCP and PEV, and a trend towards more people-centrism only during the first wave of the pandemic by BE and PAN.

Table 1 People-centrism in parliamentary debates in Portugal before and in different phases of the COVID-19 crisis by party.*

Source: Authors’ database based on the content analysis of the selected parliamentary debates. * There is no information on CH for the period January-February 2021, due to the lack of categorisable paragraphs in this period. The table therefore uses the value corresponding to that of the previous period. Presenting the value of zero for this period would lead to a wrong reading of the data: that the party had completely abandoned populist rhetoric at that time, which is highly unlikely.

A before/after the pandemic comparison (Table 1) shows that most parties do not display statistically significant shifts in terms of the use of people-centric claims. Only PAN and IL, with less than 2% of parliamentary seats together, display a trend of considerably more people-centric claims after the pandemic than before, although this does not achieve statistical significance in the case of the latter, possibly due to the low number of claims under analysis [PAN: t(682) = -1.63, p = .012; IL: t(237) = -.99; p = .102].

Regarding anti-elitism, we note a lower frequency of this element on the part of CH and IL immediately after the pandemic outbreak (Table 1). For PCP and BE, the pattern is of increasing anti-elitism during the first wave of the pandemic compared with the previous period, followed by a considerable absence of this rhetorical component. Again, a before/after comparison shows that most parties display statistically similar values in both periods, whereas IL [t(237) = 3.44; p = .019] and CH [t(372) = 2.28; p = .024] mobilised less anti-elitism after the outbreak of the pandemic.

What does this data say about our hypotheses? Hypothesis 3.1 is rejected, as there is no growth in the presence of people-centric or anti-elitist arguments by CH after the pandemic, neither during peaks nor over time. Regarding the behaviour of radical left parties (Hypothesis 3.2), our expectations would be confirmed if we restricted the analysis to the first wave of infections since BE and PCP resorted more to people-centric and anti-elite claims during this period than immediately before. If, instead, we look at the pandemic period under study at large, no pattern of increase is noticeable. Lastly, opposition parties present different patterns, to the extent that Hypothesis 3.3 cannot be confirmed.

Conclusions

In this article, we sought to analyse the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of populist discourse by political parties in Portugal. The results of the analysis allow us to conclude that, unlike our expectations, populism was less present in party discourse during the first year of the pandemic than before. We also observed that this period is roughly composed of three moments regarding the use of populist rhetoric: a slight increase in the first wave, mostly triggered by a greater presence of people-centric statements, followed by a reduction throughout the second and third waves and a slight reversal in the spring of 2021, when infections, hospitalisations, and deaths by COVID-19 shrunk in comparison with the preceding period. Although more research on the long-term consequences of the pandemic on political discourse is necessary, this limited-effects scenario leads one to conjecture that the outbreak will not have left notable marks regarding the expression of populist rhetoric among the majority of Portuguese political parties.

Moreover, we observed that the various parties analysed do not present the same pattern of behaviour over time, which aligns with the idea that responses to the pandemic are not standardised (Zulianello and Guasti, 2023). We must highlight the stability of CH during the pandemic. This party is, by a great margin, the one that most mobilises populist frames, with a special emphasis on people-centrism (as most populist parties during the COVID-19 pandemic; Ringe, Rennó and Kaltwasser, 2023). The mobilisation of populist frames by other parties is, however, slightly erratic, fluctuating across the period under analysis. Nonetheless, the overall trend is for all parties to decrease the use of populist rhetoric after a few months since the outbreak of the pandemic: after a relative peak in the use of populist discourse, specifically people-centric arguments, during the first wave of infections, the use of populist rhetoric generally shrunk.

How can we explain these trends? The most likely explanation has to do with the rallying around the flag phenomenon. In fact, there is evidence that during the pandemic there was a cooling down of the Portuguese opposition’s discourse and scope of conflict - a particularly noteworthy pattern if one compares Portugal with other Southern European countries (De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira, 2020; Silva, Costa and Moniz, 2021). In other words, after ventilating some populism in the very first months of the pandemic crisis, Portuguese parties may have decided that, in a context in which there was a common exogenous enemy to be fought, it was advantageous to put the use of populist rhetoric on hold. Opting instead for a strategy of maintaining political consensus and pursuing responsible stances, which were deemed to be more politically rewarding than the politicisation of the pandemic and its management. This explanation is compatible with the observation of an increase in populism in Spain, as in this case there was no rally around the flag effect, and inter-party conflict remained high even with the outbreak of the pandemic (Belchior and Teixeira, 2023). Furthermore, the exceptional behaviour of the CH in the Portuguese context can also be justified in light of this effect. Indeed, an extended study of populist parties’ response to the pandemic observed that instead of a rally effect, most of these parties chose to rely on strategies of political division and disruption instead of cohesion (Ringe, Rennó and Kaltwasser, 2023, p. 286).

We believe that the present research contributes to the study of supply-side populism under crisis conditions. Unlike previous research into the subject, which has mainly dealt with how economic crises have impacted populism (e. g., Lisi and Borghetto, 2018), this article examines how these dynamics play out in an altogether different sort of crisis, an exogenous shock, almost akin to a natural disaster, which is not easily adaptable to traditional divisions promoted by populist parties. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that not all crises bring about incentives for the adoption of populist rhetoric by political parties. Indeed, our results suggest that such parties might even consider it more politically advantageous to moderate their populist rhetoric under certain crisis conditions. Our results show that in the Portuguese party system, COVID-19 did not intensify signs of populist polarisation like other pandemics, such as influenza in 1918, which radicalised Italian and German politics to such an extent that it helped to pave the way for the emergence of Fascism (Galofré-Vilà et al., 2022) and Nazism (Blickle, 2020). Future research should seek to explain, more broadly, and in comparative terms, how distinct critical conjunctures influence the use of populist discourse.