Introduction

Portugal has, until recently and due to a myriad of historic, social, political and media factors, been seen as an exceptional case as regards the rise of populism. The researchers that have been analysing the Portuguese case tend to assure that national politics has proved resilient to the recent spread of populism in the European party-political systems. According to the state of the art (Lisi and Borghetto, 2018, p. 407; Marchi, 2020, pp. 47 ff; Serrano, 2020, p. 228), only after the 2019 Portuguese legislative elections and the entry in the national parliament of a radical populist right-wing party, Chega! (CH), did it become more pertinent to study this phenomenon in the country.

Since populism seems to be a relatively recent phenomenon in Portugal, that might mean that research on a subtype of populism in the country, in this case, religious populism, would be even more unlikely. However, as demonstrated by Zúquete (2022, pp. 127 ff), populist streaks have existed since the beginning of the Portuguese Third Republic (from 1974), and some religious elements can be found in this sphere. That much was clear especially from the 1990s onwards, because of one of the parties analysed in this paper, CDS - People’s Party (CDS-PP) - a conservative party, inspired by Christian democracy.

Although elements of religious populism can be found in Portugal since the 1990s, it is only from the end of the 2010s that discussing this phenomenon in the country becomes more pertinent. Indeed, the schism that took place in the summer of 2017 in the Portuguese Right, and which gave rise to CH and, later, to its entry in the Portuguese parliament (2019) was significant as regards the rise of a populist-religious discourse.

This paper thus aims to analyse two types of populism associated with the identity and cultural dimension, albeit often conflicting, typical of right-wing parties such as, in Portugal, CH and CDS-PP.

In the case of the former, the present, albeit belated, rise of the far-right in the country, and its ability to congregate part of the religious leaderships, particularly in the evangelic field, will be analysed. Its influence and ability to divide this religious segment will be examined, following the South American experience of the past years, even threatening to reconfigure this whole sector since the proposals that exclude all populisms do not accord with the values and principles of the Gospel - for example, the duty to welcome migrants and Islamophobia.

In the case of the latter, with the backdrop of its Christian-democratic matrix, the analysis will focus on how, in the past years, its process of articulating the discourse has been grounded on the narrative of the Right of authentic traditions, in connection with matters of social sensitivity associated to the image of the Church as Mater et Magistra. This will allow us to understand how religious populism operates in Portugal, the intricacies with political populism, and its practical current expression in the Portuguese Right. It will also enable the launch of research avenues for all those interested in studying this phenomenon, both in Portugal and elsewhere.

To fulfil this intention, we resorted to the theoretical base established in other work (Brissos-Lino and Moniz, 2021), also about religious populism, which will serve as the foundation for the hypotheses presented here. We start from the premise that a pertinent and contemporary approach to the phenomenon of populism in Portugal could not leave out the subtype of religious populism. We will analyse, in particular, these phenomena in light of a pair of subdimensions of religious populism: modernophobia and Islamophobia. The inquiry, following a diachronic approach using descriptive and analytical methods, will be based on content analysis of the speeches of the party leaders, of parliamentary debates, of posts in social media and, especially, of the election programmes of CH and CDS-PP. Finally, a comparative exercise will be carried out between the types of religious populism of the two parties, and their main argumentative lines as well as practical strategies will be systematised.

Religious populism

As Zúquete (2022, p. 25) states, “populism can be defined as a strategy” and, therefore, “ideology is not an end, but rather a means to achieve power”. Thus, can we find a specific type of populism in the religious sphere, based on the same assumptions of political populism, or partly so? As demonstrated elsewhere (Brissos-Lino and Moniz, 2021), the answer is yes. We agree with Zúquete’s formula, who calls it “a subtype of populism” (2017, p. 445), warning of the fact that this is a phenomenon that cuts across the religious field: “The way that this kind of religious populism manifests itself is not exclusive to any religious tradition and crosses doctrinal differences and denominational divides” (Zúquete, 2017, p. 446).

The election of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil triggered the notion of religious populism, Christian in nature. This was due to the profound influence of the populist type that some evangelical sectors had, both in the social movements and in the election campaign, during the act of taking office as president and in the constitution of and support to the new government. Something similar happened with certain Christian groups of governmental political influence, in the cases of Donald Trump (USA), Viktor Orbán (Hungary) and Mateo Salvini (Italy), as well as Vladimir Putin (Russia), here by influence of the Russian Orthodox Church. It must be said, however, that all these cases are characterized by the opposition of different branches of the Christian faith, both by the Catholic popes - since John XXIII (Pacem in Terris), Paul VI (the UN speech), John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis - and by Protestant and Evangelical sectors opposed to the populist positions, for example regarding the issue of migrants, in the name of such Christian values as human rights, solidarity, justice, peace and freedom. This populism that claims to have a Christian soul does nothing more than jeopardise the essential values of the faith in the name of other interests, triggering a process of misrepresentation of the very meaning of what is religious.

In this context, it seems useful epistemologically to focus on the possible connections that exist between religion and political populism1 and the religious phenomenon stricto sensu. Among the strategies used by religious populism, we highlight eight.

Firstly, religious leadership based on personal charisma. The religious populist aims to be empathetic with the believers, always giving them the feeling that they are just one among them. In fact, it is this charismatic ability to feign an actual connection with the masses that makes populism dangerous, whether it is found in the political or religious field. Max Weber elaborated on politics as vocation in a celebrated conference in 1917: “If some people surrender to the charisma of the prophet, of the wartime chief, of the great demagogue operating within the ecclesia or the Parliament, this means that they are held to have an inner ‘calling’ for the role of leaders of men and they are given obedience not by reason of custom or law, but because they are the recipients of faith” (2013, p. 58).

The religious populist likewise seeks to remove any other religious support that may prevent the development of a discourse directed at the people. To this end, they seek to cultivate a highly personalised discourse, so as to give the impression that they are indeed addressing each individual, even if it is through mass media, in a clear I-you discourse. In this way, the populist has a clear path that enables the creation of the illusion of proximity.

Secondly, a moralist and exclusionary discourse. When he elaborates on the populist narrative, Xavier (2017) states: “The populist discourse is nearly always moralist and exclusionary, in the sense that it is not pluralist: their followers are not only the best, they are generally the only morally worthy. And, despite accepting - often only apparently - the democratic game, they frequently despise the institutions”. This type of discourse seeks to answer effectively and definitively to social fears, whether real or imaginary. The religious populist does not air different opinions that may question the established religious order, and they do not hesitate to use authority arguments to repress them. They always seek to isolate and discredit dissidents, labelling them agents of darkness.

Thirdly, the open account of favour exchange. Just like its political counterpart, the religious populist also enters the trading market, by presenting the image of a God who bargains his favour and who exchanges blessings for money, constantly stimulating and amplifying the feeling of guilt in the needy individual. He asks the believers for offerings, providing in exchange leadership and “spiritual” protection, but also prayer for the sick, for the unemployed, the needy and the ostracised, in other words, he sells slices of hope. For those who live in desperation and constraint, any speech directed at them presenting some sliver of hope will draw their attention and attract their interest. Still all this is made on very shaky foundations, since the ability to obtain a positive answer to the longings of the destitute is returned in the shape of a stimulus to the exercise of the faith.

In the fourth place, a sectarian narrative. The religious populist claims that the other proposals of the religious market do not care about the needs and condition of people in general or are not motivated by good intentions. Therefore, they foster personality cult, presenting themselves as a longed-for Messiah that will solve all the believers’ problems. Along the way, they will do everything to try and lessen their rivals’ virtues, associating them to strategies of a satanical origin in order to undermine, divide and weaken the (only) serious spiritual ministry legitimised by God.

In the fifth place, action in the name of the divine. The religious populists declare themselves “anointed” by God to bring salvation and benediction to the poor mortals steeped in their lowly and wretched condition. If given a chance, they will influence even the political field through intervention in the name of a spiritualised reading of public life. Indeed, in its essence, populism is a worldview of religious origin that may constitute the basis for a political system, for a party or an ideology, also because it shares with fascism and communism the vision of unanimity around an imagined community (Zanatta, 2008).

In the sixth place, a nativist reaction against globalisation. The religious populist resists the integration of believers in society, fearful of losing influence and control over them, cultivating a cult spirit of a concentration-based nature. For similar reasons, they are also insensitive to human geography and, therefore, are not supporters of the confessional or ecumenical dialogue and even less so of the inter-religious dialogue.

In seventh place, the promotion of a feeling of insecurity. The enemy is central for populism (Zanattta, 2008). For this reason, the religious populist offers the masses a feeling of belonging and of common identity but does so on the back of a monolithic stance. According to Zanatta (2014), the populist seeks to divide the world into good and evil, since for them there are those who have the monopoly of identity while the others are excluded. As such, they oppose religious diversity just as the political populist is opposed to the vision of liberal democracy, which presents the pluralist principle and conceives a society organised on the basis of a contract between individuals framed by institutions.

Finally, the obliteration of the individual and their dilution in the collective. One of the interpretation keys put forward by Zanatta (2008) to understand the phenomenon of populism is that its emphasis shifts to the collective at the expense of the Enlightenment tradition, which places individual rights at the centre of the social arena. According to some beliefs especially present in the peripheral countries, populism protects from possible disintegrations produced by an individualistic view of the world. According to the same logic, the religious populist organises their form of intervention always from the standpoint of the collective, where they ensure their prominence and are less subjected to adversarial procedures and waste no time on individual relations.

As can be seen, populist action in the religious field works through a logic of mimicry with political populism, drawing on the emotions of the individuals and the manipulation of the masses. Religious populists see themselves as a kind of Messiah, upon whom the believers project their hopes from a psychological impetus which turns out to be somewhat irrational.

Dimensions of religious populism: modernophobia and islamophobia

In this section, we propose two categories of analysis to frame the phenomenon of religious populism. These categories have been developed elsewhere (Brissos-Lino and Moniz, 2021, pp. 85 ff) and concern modernophobia - understood as a (negative) reaction to the processes of modernity, namely, secularism - and Islamophobia - marked by the return of religious populist discourses and practices, against the geographical expansion of Islam.

On the former, Berger (2014) suggests that modernisation develops around a secular discourse that assumes a dominant position in society and in peoples’ minds. It essentially embodies the emergence of an immanent secular frame (Taylor, 2007) that helps people interpret the world. The assumptions and practices sponsored by the political arm of modernisation, secularism, become self-evident and are generally accepted as a natural feature of societies. These elements of secular normalisation are the pretext for a socio-political and legal practice that promotes and hegemonizes cultures of secularity. This results in a marginalisation of religion, since to achieve a social and/or political consensus agreements are mainly developed along secular lines.

The perceived primacy of political, rational, and secular authority, of a public sphere that lives mainly by immanent references, or of believers as a cognitive minority leads, according to Berger (2014, p. 15), to a fundamentalism that “balkanizes a society, leading either to ongoing conflict or to totalitarian coercion”. In effect, as some authors mention (Yates, 2007; Juergensmeyer, 2017), global modernity has transformed religious beliefs and practices, particularly through the emergence of a publicly active religious populism that advocates an absolute transcendent truth. From Muslim jihadi militants, Jewish anti-Arab activists, or members of Christian militia, they all see the world as subjugated to a secular mindset that wants to destroy their fragile religious cultures. The main argument is that the secular state, the enemy, wants to systematize its power as if etsi Deus non daretur.

The politicisation of religion and, consequently, the de-privatisation of religious populism - also as a result of the politicization of religion by the far right - develop concomitantly with the emergence of an awareness of the limits of modern secularism, especially its scientific and positivist aspects, which do not offer meaning to human existence nor lead to the integral progress of individuals. This crisis of meaning arises because the processes of social, economic, and cultural modernisation have broken with the sources of identity and systems of authority that have existed for a long time. Religion thus resurfaces with seductive answers for people in search of identity and communities of meaning in the face of the failure of modernity.

Consequently, the forms of religious populism which arise have a strongly conservative and fundamentalist bias. In other words, the current dominant forms of religious populism represent a hardening of religious orthodoxies as a reaction to the disruption, displacement, and disenchantment caused by the processes of modernity in religion.

This type of religious populism is, therefore, an expression of and a reaction to secular modernity. On the one hand, it is a reaction to modernity, a defensive opposition, normally associated with logics of cultural and/or national defense, against the individualization and privatization of religion. On the other hand, it is a modern-day phenomenon, a direct consequence of a modernity which marginalises religion.

The emergence of religious populism as a reaction against modernity, modernophobia, is essentially a reaction of political and religious rhetoric to the imposition of a unipolar global system which claims secularism as the moral compass of politics - here understood in the etymological Greek sense (politiká) which is related to the management of public affairs. It is a conflict between global (secular) modernity - imperialist and monocultural - and territorial (religious) nativism - as a cultural reaction or defense.

Islamophobia, as an aversion to the religion of Islam or Muslims in general, is another subtype of religious populism which, according to several authors (Mudde, 2007; Apahideanu, 2014; Brubaker, 2016), emerged mainly in the West after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, the expansion of globalization and its subsequent international migration phenomena, and the September 11 attacks and international coordination in the fight against terrorism. Islamic terrorism has begun to be seen as a driving factor behind anti-Islamic sentiment in Europe and around the world, not least because of the security narrative that has developed around the myth of religious violence (Cavanaugh, 2009). Thereafter, as Mudde (2007, p. 84) explains, Islamophobia “took center stage” in the political discourse of the “Western world” causing an increase in Islamophobic reaction. With these developments, Huntington’s (1996) prophecy of a clash of civilizations begins, as the West comes to understand itself at odds with a Muslim imperialist world.

This shift was partly a reaction to the arrival of immigrant populations who identified themselves as Muslims. Nevertheless, it was essentially due to a growing regional, European, and civilisational preoccupation with Islam than to major social demands from European Muslims. It was precisely this civilisational concern of the Judeo-Christian, but mostly Christian, European matrix with Muslims that became particularly prominent in European religious populism, namely that linked to a certain right-wing populist discourse. The notion concerning the protection “liberal and Western values against Islam” has become the new “master frame” for religiously motivated populism ( Brubaker, 2016).

In this context, populism in Europe developed a new religious/Christian dimension of religious discourse and practice that comes under an ideological umbrella called “nativism” by Mudde (2007, pp. 18 ff). To some extent, this subtype of religious populism - Islamophobia - prescribes, on the one hand, that every country should be inhabited mostly, if not exclusively, by members of the native group; and, on the other hand, that non-native elements, such as people and ideas, are a fundamental threat to the idealised homogeneity of the native group. To create a native identity, it is necessary to contrast it with those considered non-natives. As Apahideanu explains, a “new enemy” that threatens the religious identity of the unity between state and people has been “rapidly, integrally, and definitively identified as the Islam”. In a word, “a new form of religious populism gained hegemony in modern Western Europe: Islamophobic populism” (Apahideanu, 2014, p. 85).

Thus, this new form of religious populism implicitly or explicitly refers to a Christian collectivity (we, the ingroup) that suffers an invasion by Muslims (the outgroup) (Mudde, 2007, pp. 63-64). Muslims are characterized holistically (Islamism) and antagonistically (e. g., violent and backward). Regarding the cultural dimension, this religious populism prescribes some restrictions on the religious rights of Muslims (from banning the building of minarets to prohibiting certain religious habits) while advocating the restoration and preservation of Christian roots. The characteristics of the outgroup, as a representation of the enemy, are then very clearly and explicitly defined, while those of the ingroup, the European Christians, remain vague and abstract (Mudde, 2007, p. 64). The distinctions between Christianity and Islam are understood, for Islamophobic religious populists, in a framework of normative oppositions: between liberal and illiberal, individualist and collectivist, democratic and authoritarian, modern and retrograde, and secular and religious, respectively (DeHanas and Shterin, 2018, p. 178).

This kind of religious populism perceives religion primarily in cultural and civilisational terms, in antithetical opposition to Islam. Religion is first and foremost an identity marker that allows the distinction between the good and the evil. The instrumentalization of religion by populists, in the West, essentially serves to differentiate the nation or people from others who threaten them, i. e., Muslim immigrants. As Roy writes, this religious populism is “Christian to the extent as it is anti-Muslim”. Moreover, Christianity as a national identity is such a “superficial” cultural layer that it becomes easily “hijackable” by populists (Roy, 2016, p. 186). This is confirmed by Cremer (2023a, p. 1) when he states that populists use Christianity as a marker of cultural identity for the “ ‘pure people’ against external ‘others’ while often remaining disconnected from Christian values, beliefs, and institutions”. In essence, Christian identity has the dual purpose of building nostalgia for a glorious national past and of transforming Islam into an intrinsically non-native culture. As happened to Jews in Europe, especially during World War II, “Islamophobia has become their contemporary counterpart” (Mudde, 2007, p. 84).

Ch and religious populism

From the beginning, CH has opened its doors to the Evangelical sector, traditionally little involved in politics, seeing to attract this religious segment to itself - the second numerically most significant in Portugal, following the Catholic -, taking advantage of the conservative agenda as regards costumes, inscribed in its manifesto.

Besides, part of the sector further to the right of the Evangelical spectrum joined CH as soon as the party emerged in the Portuguese political spectrum, although another part opted for a kind of trend within CDS-PP called “Logos”, which has since then been extinguished.

At the root of this swerve to the right in a religious setting, typically conservative and apolitical, emerge two fundamental reasons. On the one hand, the political discussion of the so-called divisive causes, fostered in later years by Parliamentary parties further to the left, and which involves a greater opening to abortion, same-sex marriage, the legalisation of soft drugs, legislation on gender reassignment, sex education in public schools, and euthanasia. This religious segment felt the so-called moral agenda, particularly sexual morals, was in danger, thus creating a climate of insecurity and fear.

Then, all it took was for the far-right embodied in CH to ride this wave to emerge as its political flag, conveying the sensation of giving them a voice and of feeling that for the first time that, as minority, they now had someone to speak out for them. Now, this is no small thing for individuals who have always felt at the margin of political power, with no influence and excluded from the governance of the country’s course. Thus, CH came across as a convenient loudspeaker for their frustrations, social irrelevance, and political powerlessness.

Conversely, the experiments of Trump in the United States and Bolsonaro in Brazil inspired this religious fringe to believe that such models could be replicated in Portugal, models which in these regions elevated religious leaders to the corridors of power, where they were then able to enforce their ideology and private and group interests.

Nevertheless, the leader of CH - who wanted to be a priest and attended the Penafirme Seminary, a minor seminary of the Patriarchate of Lisbon - understood that Portugal has a cultural Catholic tradition, and therefore worked to be photographed on altars, since he needs to conquer the right-wing Catholic people as well as that majority, which, albeit non-practicing, was given a religious education or still operates in that tradition.

Marujo (Público, 24-07-2022) remarks that it is odd that “[…] a politician who goes to mass and takes the holy communion should see enemies and evil people in so many beings - and even more so in gypsy people - and forget the precept of love for one’s neighbour and enemies- the greatest Christian imperative”.

CH was founded on 09-04-2019 and seems to be a unipersonal party, built around André Ventura (AV), the leader and founder who had previously become known in the public area by being a resident commentator in a tabloid-like sports programme, aired on a cable television channel. AV was the only Member of Parliament elected in the XIV legislature, ran for president and was the party’s only visible face for the first years. His political discourse was always aligned with that of the European far-right populist leaders and parties with whom he had close political ties, such as Santiago Abascal and VOX, in Spain, Marine Le Pen and Rassemblement National, in France, or Matteo Salvini and Lega, in Italy.

Therefore, like other European political parties and leaders, more ( Giorgia Meloni) or less recent (Viktor Orbán), CH still derives inspiration from a Christian right wing that in the past decades has developed close ties to the American conservatism, but which never reached such a high point as during the Trump administration (Cremer, 2023a, pp. 1-4, 23). Propelled by conspiracy theories such as the theory of stolen elections (2020), this was heard in a rally of the former president, in Michigan, in late April (2022), an Evangelical religious leader said this prayer: “Father in heaven, we firmly believe Donald Trump is the current and true President of the United States” (Graham, 2022, p. 33).

Thus, whether due to the political leadership system or to the fact that this party does not have significant critical mass, CH does not impress by the clarity of its manifesto, which is frequently lacking in many topics, or altered depending on the interests of the political moment.

CH is engaged with the predominant religion, by defending “the Portuguese cultural identity” to “preserve, defend and enhance the cultural heritage and the Portuguese traditions”, with a view to ensuring that “the State is not allowed to programme education and culture according to any philosophical, aesthetical, political ideological or religious directives” (2021). These vague statements show how CH’s arguments remain disconnected from Christian values, beliefs, and institutions (Cremer, 2023a), providing evidence that in Portugal, as in Western Europe, populism is increasingly dominated by a “post-religious right-wing identity politics” (Cremer, 2023b, p. 41).

Thus, the party’s political manifesto is silent on the matter of religious freedom (Programa Político, 2021), an important topic which constitutes one of the pillars of the Portuguese Constitution and provides the foundation for the Law of Religious Freedom, published twenty years ago.

“Article 1 (Law of Religious Freedom)

“Freedom of conscience, religion, and worship

“Freedom of conscience, religion and belief is an inviolable an assured to all pursuant to the Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights international law and the present law”.

“Article 13 (Constitution of the Portuguese Republic)

“Principle of equality

“1. All citizens have the same social dignity and are equal before the law.

“2. No one can be privileged, treated with partiality, harmed, deprived of any right or exempt of any duty by reason of ascendency, gender, race, language, territory of origin, religion, political or ideological convictions, education, economic situation, social status, or sexual orientation”.2

As if such omission was not enough, CH also favours, in the name of what it terms national cohesion: “the duty of safeguarding the sociocultural cohesion of Portugal and of Europe against the rise of multiculturalism, considering that the peoples should take responsibility for the self-esteem and self-preservation of their human, historic and civilizational dignity” (Programa Político, 2021, §60). In other words, refusing multiculturalism and, at the same time, the so-called “civilizational preservation” and the “sociocultural cohesion of Portugal” will mean nothing other than the rejection of openness to other cultures and religions, in a blatant contrast not only with the spirit and the letter of common law but also, especially, with the sovereign law of the country.

AV has contrived to be photographed in sanctuaries and claims to venerate the Virgin Mary. He claims to be Catholic, attends mass and takes the Holy Communion. As explained in Dias (2022, p. 96) to acquire a religious aura, AV uses elements of popular Portuguese religiosity, such as the Miracle of Fátima presenting himself “as someone anointed by the power of the Virgin Mary”. The party has been building a narrative around the good Portuguese, based on the Catholic morals, but only along the dimensions that are of interest to him. This fits with AV’s “political-messianism”, which emphasises the pure people, those who represent Portugueseness, and “opens the way to a modern Sebastianism” (Dias, 2022, p. 93). Social justice issues, such as the social doctrine of the Church (SDC), or the support to migrants and refugees are absent since they do not align with the nationalist and nativist theories.

Marujo (Público, 24-07-2022) brings to light how the alleged Christian inspiration of the ideology of CH does not stand up to a brief Biblical and theological analysis:

[…] [I]n many aspects, Chega defends the opposite of the Gospel and of the Christian (and Judaeo-Christian) tradition. […] A page of this newspaper would not suffice to reproduce the dozens of quotes, warning, pleas from God Himself on this topic (for those who believe that God speaks in the Bible, of course). Such as this one, from Leviticus (19, 33-34): ‘And if a stranger sojourn with thee in your land, ye shall not vex him. But the stranger that dwelled with you shall be unto you as one born among you, and thou shalt love him as thyself: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.’ […] Is it worth also recalling the plea in Exodus (23, 9) for the stranger not to be oppressed? Or the warning of prophet Malachi (3, 5) against those that ‘oppress the hireling in his wages’ and those ‘turn aside the stranger from his right’?

Moreover, if we turn to the New Testament, the same tone can be found there as well:

Jesus continued in this vein, naturally, regarding bandits, prostitutes, adulterers, strangers (the Samaritans or the Roman centurion), prisoners and all the outcasts of the time Israel. ‘For I was an hungered, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in: Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me.’ (It’s in Matthew 25).

Regarding Islam, CH proposes that the Portuguese state create a surveillance system for the whole Muslim community in Portugal (Observador, 03-11-2020), under the pretext of preventing radicalism and fundamentalism, after it defended, in the past, that the immigration of Muslims constituted “a danger to Portugal”, in line with the strong Islamophobic bias of the European far-right (Jornal de Negócios, 06-05-2021).

Meanwhile, AV had already previously suggested “confining” the Roma people (TSF, 06-05-2020), a clearly discriminating proposal and one which violates the Portuguese Constitution, also in line with the identity populism which manifests itself against the minorities everywhere in the world where discriminatory experiments of ghetto-creation have always yielded terrible results.

Furthermore, CH wants to change Article 30 of the Portuguese Constitution, which bans life imprisonment for some crimes, after it fed the idea of chemical or even physical castration for rapists, taking advantage of the common citizens’ widespread repugnance for such crimes, while denying the rehabilitating and reintegrating role of penal justice in any civilised state under the rule of law (Diário de Notícias, 26-06-2022; Público, 22-09- 2020).

It is, probably, due to positions such as this one that Marujo (Público, 24-07-2022) refers to hints of a fascist-type ideology in the party’s doctrine:

Is it an exaggeration to speak of fascism? It has always been on the rejection of the other and of the difference that all fascisms germinated (and continue to do so). Be they those that led to the unspeakableness of the Shoah, or the salvinis, orbáns, erdogans, modis or putins of present times. I have no doubt that if Chega were in power there would be no place for democratic disagreement, for the search for consensuses and the respect for human dignity.

While we cannot speak of fascism, considering that such ideology is characterised by specific, historically-defined identity marks, still it is possible to identify in the manifesto of CH a fascistic bias as a result of the nativist, justicialist, exclusionary, nationalist and even xenophobic ideas that can be detected both in the doctrine and in the practice of the party, and which involve a clearly populist practice, of which the religious element is a part.

As final remark, it is important to mention that in late 2020, several right-wing Evangelical activists held a meeting in the north of the country aiming at the possible creation of an Evangelical political party. Since no agreement could be reached, some members and supporters of CDS-PP then chose to create a sort of group of Evangelical activists in this political force. To this end, as already mentioned, they created a page on Facebook (“CDS Logos”) and a blog on Wordpress, while others joined the new party CH.

It should also be stated that lately CH has been distancing itself from the Evangelical sector, especially by AV, including activist elements. Although there has never been any kind of institutional, or even tacit, support from the Evangelical sector to CH, but merely individual memberships, a political interpretation can be made here. The leaders of CH may have concluded that the party could receive more votes by supporting the Catholic religious segment, since in Portugal the Catholic Church far outnumbers the Evangelical. Hence AV’s media investment, with photos next to Catholic altars as well as the references to Fátima. This will be another topic to follow.

CDS-PP and religious populism

The connection between CDS-PP and the populist discourse is not new. On the contrary, some studies mention the fact that since the early 1990s this party, especially under Basílio Horta (Robinson, 1996, pp. 968-969), started what Zúquete (2022, pp. 33 ff) called “regenerating populism”. This type of populism of the Christian-democrats comprises traits of a popular right-wing representative of those that feel disgruntled with the system.

Still, the authors are unanimous in the conviction that it was under the leadership of Manuel Monteiro (1992-1998) that the party took a truly populist (Robinson, 1996, pp. 969-971; Zúquete, 2022, pp. 159 ff), “anti-elitist” (Lisi and Borghetto, 2018, p. 414) and anti-system turn (Zúquete, 2022, pp. 166-167), with a tinge of a universalist, Christian-democratic right.

Although the mainstream parties that can aspire to government, such as CDS-PP, resist populist discourse, the history of CDS-PP in the 1990s and 2000s was an exception. The right-wing, interclass, populist narrative, focused on moral values and, with that, the subordination of politics to morals became imbedded in the party’s leaders. One example of such persistence and the impact of political leaders in the appropriation and dissemination of certain elements of the populist discourse was Paulo Portas (1998-2005 and 2007-2016).

In addition to maintaining the previous type of populism, with Portas, the “identification with the people […] was often complemented with religiosity” (Zúquete, 2022, p. 172). The most explicit use of religious elements became one of the hallmarks of CDS-PP. This was reflected in some political banners typical of religious populism, such as: the fight against abortion as a reflection of the crisis of values - modernophobia - or insecurity, multiculturalism, or the defence of the Portuguese people, as a demonstration of the attack on an idealised Christian monoculture. This demonstrated traits of xenophobia, albeit not necessarily of Islamophobia. As underlying element, this religious populism was marked by a specific “link to Marianism” (Zúquete, 2022, p. 172) - the Virgin Mary, a constant in Portuguese and peninsular culture - and this would be inseparable from the party’s next steps.

In fact, this path was continued with the new leadership of Assunção Cristas (2016-2020). Enlightening is the way she was called to join the party, after her participation in a television program in 2007, where she defended the “no” in the referendum campaign on the decriminalization of abortion. Cristas was a leader who “could not imagine herself without faith” (Diário de Notícias, 16-01-2016) and who assumed herself as a “practising Catholic”, inspired by Jesus Christ “in His example and insight” (Jornal de Negócios, 12-03-2016). In an interview, she even stated that her Catholic upbringing was “very important” for her political intervention, and she quoted a passage from the Bible to justify her entry into politics (Expresso, 02-07-2011).

This construction of the image of a political leader with a religious aura would bring the party even closer to some typical features of religious populism. Chronologically, for example, April 2016, regarding an international matter, CDS-PP proposed, in the national Parliament, a vote of condemnation n.º 70/XIII (Plenary Meeting, 29-04-2016, p. 41) on “genocide, motivated and pressured by fundamentalism and religious radicalism whose mobilization and cruelty reached extraordinarily worrying levels upon Christians […] in Africa and the Middle East.” The condemnation of the “genocidal and heinous” actions of such groups as the “Islamic State”, especially upon “Christian communities”, clearly marked the dichotomy between a specific aggressor and a concrete victim, among other religious minorities. At national level, another example emerged in August 2016, when the party opposed the socialist government’s position to the Catholic church’s view on the collection of Municipal Property Tax. Cristas accused the government of “ideological blindness” and of “disrespecting the Concordat” (Rádio Renascença, 29-08-2016). In a dispute between the political and religious spheres, the Christian-Democrat leader also questioned why the “government did not tax the assets of political parties” (Rádio Renascença, 09-08-2016) rather than the religious assets.

Another relevant moment happened in October 2017 when Cristas went to the Sanctuary of Fátima to participate in the celebrations of the centennial of the apparitions. While, on the one hand, all the leaders of the parties represented in Parliament distanced themselves from the celebrations; on the other hand, the leader of the CDS-PP was present “with her family” and participated as “pilgrim” and “devout” (Observador, 29-04-2017). In this context, it is also emphasized her participation in the panel “Fátima and Family”. This political-religious imaginary, Christocentric and Marian, would lead to a split that would leave its mark in national politics and, above all, on how a religious populism would develop in Portugal (Marchi, 2020a, pp. 40 ff; Marchi, 2020b, p. 203).

In July 2017, CDS withdrew support for its candidate to the Loures Municipality, André Ventura, after statements concerning social benefits and the Roma community. CDS, through its president, considered the remarks of the future leader of CH to be racist and xenophobic. She asserted that they were incompatible with the “principles founded on Christian democracy, on the absolute respect for every human being”, upheld by CDS (Diário de Notícias, 20-07-2017). Even at the risk of immediate and future electoral losses, the party called upon itself to defend a pure Christian democracy, as opposed to a religious view of non-universalist and discriminatory politics, the media seed of which was Ventura.

From this, a schism of religious populism in Portugal ensued. On the one hand, CDS began to assume the religious phenomenon as something fundamentally value-based; on the other hand, CH would look at it, above all, through the identity dimension, as generally described in Marzouki, Roy and McDonnell (2016). In other words, the former would use the political-religious imaginary as a matter of faith, theology, or belief, showing greater consideration for the effective promotion of religious values; while the latter would use this imaginary for more strategic political purposes, resorting to religion to justify the need for protection of native, Christian people.

The association, whether implicit or explicit, of the party to the religious imaginary continued, for example, with CDS-PP’s dissenting vote to the law on gender self-determination from the age of 16 (2018), in line with the position of the Catholic Church; its vote against euthanasia (2018) and the Patriarchate of Lisbon’s appeal, for example, to the vote for CDS-PP because it had “a position similar to that of the Church on pro-life issues” (Observador, 16-05-2019); the alignment with Pope Francis’s encyclical letter Laudato si’, especially in the criticism of modernity and the need to “adopt lifestyles compatible with environmental sustainability” (Project of Resolution, 02-02-2018, p. 68); the fight against corruption in justice and the lack of transparency in political activity, and the consequent need to protect the “weaker and more disadvantaged” who would “certainly” not be forgotten by “Christian democracy” (Plenary Meeting, 26-10-2019, p. 11).

The manifesto of CDS for the 2019 Portuguese legislative elections also reveals this narrative of protection of Christian values:

[…] [F]undamental values of the European social model […]. We want to implement reforms to ensure the feasibility of a fair and efficient State, that reaches out to all and that ensures access and freedoms for all. And we want to do it in the deepest respect for the tradition of Christian democracy […]. [Programa Eleitoral Legislativas, 2019]

These value-based intentions and the distancing vis-à-vis CH became clear, for instance, in the sections “Conditions for building a family life project”; “An uncompromising commitment to the defence of life: no to euthanasia”; “Respect for the freedom of each individual”, including that of race, territory of origin and religion; “Support for refugees” fleeing religious persecution, among others; “In the heritage where we live”, calling for the defence of Portuguese traditions and cultural expressions; or “We believe in a Social State of partnership”, where the collaboration with institutions of religious inspiration or matrix and volunteering should be highlighted, as a synonym of social generosity.

Poor results in the 2019 legislative elections (4.22%) led to Cristas’s resignation and opened the way for the ascent of Francisco Rodrigues dos Santos, for a term that began in January 2020. At the inauguration, it became clear, according to Marchi (2020b, p. 203), that the new CDS would maintain its “liberal-conservative and personalist Christian Democratic nature”, although “more radical traits with regard to the defence of pro-life, pro-family values, and opposition to the left-wing agenda dubbed ‘cultural Marxism’” were intensified.

Researchers such as Nuno Pereira de Magalhães generally considered that the CDS-PP of Rodrigues dos Santos was not of the radical populist right-wing, but only conservative. This emphasis on conservatism helped to strengthen the religious dimension, through the party’s defence of the “respect for traditions compatible with a Christian-inspired humanistic moral system” (Observador, 24-04-2020). However, for others, such as Telles (2021, pp. 99 ff), reading the party’s posts on Facebook demonstrates how their communication style can be considered populist, especially on three levels: people-centrism, attack on political elites, and family and religious values. Regardless of whether Rodrigues dos Santos’ CDS-PP is perceived as populist or not, the presence of religious values appears to be transversal, being “conveyed in conjunction with the references to the people and anti-elitism”.

The analysis of other elements, such as parliamentary debates, legislative proposals, and public speeches, shows traits of a populism with religious elements that, in different ways, accompany the tradition of Monteiro, Portas or Cristas. For example, the presentation of Pope Francis’s encyclical letter Fratelli Tutti in the Legislative Assembly of Madeira by its president, José Manuel Fernandes (CDS-PP), who said it should be “mandatory reading for all political leaders”, as it was a “punch in the stomach […] against the haughtiness, superciliousness, superiority, arrogance that sometimes dominate the decision-makers of our collective life” (Agência Ecclesia, 29-10-2020) - religion against political elites. Another example was the way it actively continued to fight the euthanasia law. The declarations of its parliamentary leader, Telmo Correia, must also be recalled, when he said that passing the law would mean that the State “only has to offer the Portuguese death” (Jornal de Notícias, 29-04-2021); or the statements of the President of CDS-PP, who accused the Portuguese parliament of contributing to the “moral swamp” and that it would be up to the party to defend the “values of life and dignity of the human being from conception to natural death” - (Christian) morality to protect the dignity of the people. Finally, we can see it in the affirmation of CDS-PP as a “ humanist party with a Christian democratic matrix” (Plenary Meeting, 12-11-2021, p. 8), the “representative voice of Christian democracy” in Parliament (Plenary Meeting, 27-04-2020, p. 12) or as “Christian democrat, looking for paths to boost the most vulnerable, the most forgotten, the underprivileged” - religion as a value-based element in favour of the most disadvantaged of the losers of modern societies (Plenary Meeting, 28-04-2021, p. 52).

This would become even more evident in the political manifesto of CDS-PP for the 2022 legislative elections (Compromisso Eleitoral CDS-PP, 2022). For instance, in the reinforcement of the Christian matrix and its inherent values:

JUDAEO-CHRISTIAN ETHICS, (i) axiological cement of the Western civilisation, (ii) base of the national identity, (iii) assumption of a State of human rights and (iv) foundation of a Christian democrat, conservative ideology.

In religion as element that fosters and protects the people’s dignity:

DIGNITY OF THE HUMAN PERSON, which involves (i) the uncompromising defence of life, from conception to natural death, (ii) the assurance of the citizen’s freedom vis-à-vis the State […]. Caring for our elderly, reducing structural poverty, and fighting the exclusion that offends human dignity is a duty that the right-wing of social, Christian nature cannot shirk.

In the defence of traditional values, against the moral decline of modern societies:

FAMILY, underlying cell of society, (i) fostering important personal development factors and core of freedom which must be protected […]. Freeing education of ideological ballasts, refusing indoctrination by the State, and acknowledging family’s role in the transmission of values. Defence of the Rural World, of its culture, memory, and traditions: hunting, bullfighting, and all cultural manifestations […]. Preventing any external forces from interfering in the traditions of the Armed Forces, in their specific culture or in their symbols.

Finally, in the protection against the State and elites:

Armed with its usual values, the right Right [Direita Certa] protects, frees, and fights. It protects life as well as our way of life. It frees […] the citizen […] from a patronising State held hostage by the political and intellectual left. It fights, in defence of the citizens, against the interests that have taken hold of the State. […] Actively fighting corruption, be it at the judicial level, or at the level of the administrative activity. […] Defining the crime of illicit enrichment (public office holders and high public office) […]. Increasing the penal framework for the crimes committed by public office holders and high public office; Removal from office and disqualification from public office holders […].

Through the analysis of these elements, it becomes more evident how, against the background of the Christian democratic matrix, CDS-PP has been basing itself on the right-wing narrative of authentic traditions in connection with issues of social sensitivity associated with the image of the Catholic Church as Mater et Magistra. This type of populism, grounded in the values of family and religion, is close to the modernophobia model of religious populism, in particular by its negative reaction to progressive political proposals, such as medically assisted death (understood as an attack on the sanctity of human life); gender ideology (interpreted as inculcation, in schools, of values antagonistic to the family); historical revisionism (as opposed to the country’s cultural and religious identity); the crisis of values (against Portuguese Christian society); and the attack on traditions (as a reflection of an absolute, absorbing modernity).

These positions were deepened and sometimes taken to extremes during the television debates. For example, in the debate with the CH leader, CDS-PP affirmed its right wing as “patriotic” (Jornal de Negócios, 12-01-2022) and defender of the “values of the SDc” (Jornal de Notícias, 12-01-2022). By claiming fidelity to the positions of Pope Francis and Christian democracy, Rodrigues dos Santos again distinguished between a pure, value-based view of the Christian democracy of CDS-PP, as opposed to a religious view of politics that showed “racist” traits, defended “ethnic segregations” (Jornal de Negócios, 12-01-2022) and used typical elements of “religious sect” (Visão, 12-01-2022) such as that of CH. Moreover, regarding gender identity, the leader of CDS-PP said that the State, through the school subject of Civic Education, had become a “vehicle for conveying gender ideology” (Público, 11-01-2022). On the contrary, he argued that this school subject should “become optional - as is already Religion and Morals” (Diário de Notícias, 09-01-2022). This even led the Portuguese Prime Minister, António Costa, to criticize the party, accusing it of confusing “religious beliefs” with “the values enshrined in the Constitution” (Diário de Notícias, 09-01-2022).

Once again, the party scored poor results in the January 2022 legislative elections, leading it to lose parliamentary representation for the first time in its history. Following this event, Rodrigues dos Santos resigned, and Nuno Melo was elected president (April 2022).

Although it is still early to make an analysis of the positioning of Melo’s CDS-PP, there seem to be some elements of continuity. For example, in his Global Strategy Motion, the president of CDS-PP recalled Europe’s “Judaeo-Christian legacy” and stated that the party would follow a “Christian democratic” line (Moção de Estratégia Global, 2022). He recalled that “CDS is a party of values”, concerned with protection of “the voluntary termination of pregnancy and euthanasia” (Moção de Estratégia Global, 2022). In addition, he expressed concern about the issues of historical traditions, “that honour us so much and we will always bear in mind”, and justice, wishing to put an end to “a system for the richest or for the poorest of the poorest” (Moção de Estratégia Global, 2022). In other words, there seem to be some foundational elements that will allow a continuity of the previous line. In particular, the proclamation of a Christian identity, in its value-based dimension - as opposed to an amoral view of politics -; the defence of the national traditions - in contrast to the relativity of modernity -; or the defence of the weakest, particularly with pro-life positions - as an alternative to the violability of human life and its dignity.

These elements will tend to grow with CDS-PP outside the Portuguese parliament and without government responsibilities at national level. Its historic shift to the category of challenger party, rather than mainstream, could have consequences. Even when it was in the parliament, it was possible to find elements of religious populism in CDS-PP from the 1990s to the present day. According to Lisi and Borghetto (2018), the rhetorical style and discourse strategy differ significantly in line with the position in the political game, with challengers tending to present bolder manifestos and ideologies than the mainstream parties. The fact that CDS-PP had been part of this group of possible government parties (arco da governação) in Portugal since the late 1970s might be a mitigating element. However, on the basis of i) the religious populist marks in the party’s past, including the recent past, ii) the line of ideological continuity and the discourse that has been followed, iii) the impact of the party’s leadership on the modelling of party rhetoric, and iv) the shift to the status of challenger, there seems to be no shortage of reasons to continue examining the religious populism of the CDS-PP in the future.

Comparative analysis

In the field of religious populism, Portugal is not, and has never truly been, an exception. Indeed, as demonstrated in the case of CDS-PP, since the early 1990s we can speak of a regenerating populism, with religious streaks. With advances and setbacks, the following decades served to deepen this phenomenon and to structure it. In the mid-2010s - with the presence of CDS-PP in a coalition government and with a certain easing of its religious populist discourse - and especially towards the end of this decade - with the arrival of CH to the Portuguese political scene - there was a restructuring, a schism, of national religious populism.

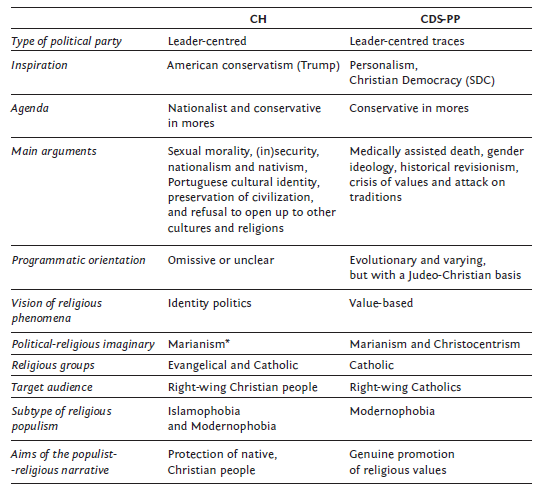

In this final stage of the work, to better understand this reality, we offer a comparative systematization of some (dis)similarities between the types of religious populism analysed above.3

Table 1 makes it easier to read and compare the elements analysed throughout this article. In fact, their articulation with the strategies and dimensions of religious populism analysed in sections 1 and 2, seem useful to understand the features of religious populism in Portugal.

Thus, some dissimilarities between the parties and their religious populist discourse are identified. Differences stand out in three essential points. Firstly, the starting point, with CH and CDS-PP being inspired by a religious populism close to the Trumpist model and the SDC, respectively, which conveys a notion of action in the name of the divine. Secondly, in its speech, with CH resorting to the religious populist narrative to advance a nationalist and identity agenda (an example of moralistic and exclusionary discourse), while CDS-PP uses it to ground and legitimise its political-religious (value-based) imaginary. Finally, in the underlying intents, that is, in a neo-nativism that is as Christian as it is Islamophobic (or Roma-phobic or xenophobic), in the case of CH (an example of the sectarian narrative), and the defence of a personalist Christian democracy, the ultimate end of which would be the promotion of religious values.

On the other hand, some similitudes can be found. At least five stand out. The first concerns the religious sectors supported or that offer support. In both cases, Christians. However, in the case of CH, perhaps, as an example of an open account of favour exchange, there is a more evident integration of Evangelicals4. Secondly, religious leadership based on personal charisma and a certain religious appeal - justification of an action in the name of the divine - the case of AV in CH and Manuel Monteiro or Paulo Portas in CDS-PP. Thirdly, in the main arguments adopted, which may be broadly-speaking integrated into the categories of promoting a feeling of insecurity and nativist reaction against globalisation, although this is currently much more evident in the case of CH. Here, it should also be noted that other ideological battles such as euthanasia, sexual morality and gender ideology are subjects generically shared between both parties, although with more systematized thinking in the case of CDS-PP. Finally, on the issue of the subtype of religious populism, due to its conservative agenda on customs, both reveal streaks of modernophobia. Still, only CH, because of the need to feed its exclusionary discourse and its nativist reactionism, currently presents true signs of Islamophobia.

Table 1 Religious populism: CH and CDS-PP in comparative analysis.

Source: Authors’ compilation. * It should be noted that Christocentrism can also be found in CH, notably in its Evangelical sector.

In this context, it is important to highlight that the existing similarities are due to the fact that some of the original populist elements of CDS-PP - the regenerating populism of a popular right-wing representative of the disgruntled of the system - have transitioned to CH, in particular the elements advocating the subordination of politics to morals. This substitution or appropriation of populist arguments by CH seems to be ideologically correlated with AV’s previous proximity to the Portuguese mainstream right (from which he derived his political-religious imaginary). However, it seems to be temporally correlated, above all, with some more recent moderation of CDS-PP’s discourse, following the line of Lisi and Borghetto (2018). With this, and with the schism of the Portuguese religious populism in 2017, CH became closer to religious groups, notably Evangelicals. It also found an edge to seek some of the disgruntled of the system that were traditionally voters of CDS-PP and with whom the religious populist narrative worked fairly effectively. Thus, as CDS-PP became more moderate with the proximity to and the exercise of power, it eventually left the narrative of political morality - Christian, nationalist, inter-classist, anti-elitist and anti-system - up for grabs.

Final remarks

What then is the future of religious populism in Portugal? It is unpredictable, since CDS-PP has lost parliamentary representation for the first time since 1975, and CH remains very centralised in the person of AV. In the case of the former, its removal from the centre of power, symbolic or real, can lead to a radicalisation of its positions. However, a possible greater emphasis on the subordination of politics to morals may be inconsequential if the party does not regain and retain parliamentary representation. In the case of the latter, given the dependence on its charismatic leader, and the fluctuations and insecurity that can arise from this, it is not foreseeable that great coherence will develop around religious populist elements (e. g., the bases of the manifesto, the sectors of religious support, or the causes that drive its action).

Nevertheless, one thing seems certain: the current Portuguese political context has followed the trend of de-privatisation of religion, and of the growth of its prominence in the public space and in political agendas. It was, therefore, natural that new forms of articulation between politics and religion developed, both in the more traditional sense, as in the case of CDS-PP, as in its reinterpreted form, as in the case of CH.

Religious populism has become, in a sense, a new avatar of the political crisis(es) (Mabille, 2019) and of the identity and value-based wars of modernity. In particular, with the greater prominence of certain political parties, such as CH, and with the return of others, such as CDS-PP, with religious ideological references and with the support, formal or informal, of churches and religious communities.

If the future of religious populism in the country seems uncertain, the need for the continuous study of this phenomenon in Portugal and across borders seems less doubtful. We believe that this study can open doors to understanding how mainstream party politicians and religious leaders in Portugal and elsewhere will act and be willing to employ religion either to legitimise populists’ identitarian use of religion or challenge it. Furthermore, it contributes to the discussion on how the historical availability of a Christian alternative in the party system (CDS-PP) can increase or decrease a social taboo around the new populist right (CH) and how this can affect voters in a national election. We hope that this work provides at the very least a contribution towards these ends.