Introduction1

Populist parties have gained increasing traction since the 1980s, gradually transforming the European political landscape (Mudde, 2004). The literature on populism tends to focus either on conceptual issues, or on the supply-side of populism (parties, media, or political leaders). Populism’s support base has also attracted growing academic interest, albeit to a lesser degree (see Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020). Extant research has sought to understand why people support populist parties, focusing on voters’ values, voting patterns on (or identification with) populist parties (Baro, 2022), ideological leanings (e.g., Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove, 2014; Norris and Inglehart, 2019), and social belongings (Langenkamp and Bienstman, 2022). An important, albeit relatively unexplored demand-side dimension of populism, pertains to the relationship between personality traits and citizens’ support for populism (Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga and Borah, 2023). These are characteristics that manifest very early in one’s life and remain mostly unchanged ( Mondak and Halperin, 2008). The psychological correlates of populism have been addressed by isolating specific personality traits - see Bakker, Rooduijn and Schumacher (2016) on agreeableness - highlighting that such correlates are dependent on the political and historical background of different countries (Fatke, 2019). Such research has called for comparative country case studies to provide a deeper understanding of the growth of populism.

This research seeks to fill this gap by analysing the relationship between personality traits and citizens’ populist attitudes in Portugal. While the current populist wave arrived in Europe many years ago, it only broke on Portugal’s shores in 2019 when the populist radical right party Enough (Chega, CH) gained representation in parliament (Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020; Mendes, 2021), putting an end to the so-called Portuguese exceptionalism regarding populism (Salgado and Zúquete, 2017). Up until 2019, however, Portuguese citizens with populist attitudes were very hard to identify, given the lack of parliamentary representation - which might have caused many to redirect their vote to other parties that partially satisfied their preferences (Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020).

This research maps Portuguese citizens’ personality traits, using the Big Five Personality Traits model (McCrae and John, 1992), and addresses their relationship with citizen’s support for populist attitudes. Overall, the article indicates that populist attitudes are associated with extroverted, conscientious, and neurotic individuals and that this association holds even when accounting for political efficacy, party affiliation, and demographic factors. It also finds that supporters of populism are typically conscientious, have lower political efficacy, tend to be male, older, and often have lower levels of education. Furthermore, strong populist attitudes often stem from alignment with parties that embrace populist rhetoric, which can intensify such attitudes.

The paper is structured as follows. The first section begins by conceptualising populism and reviewing the research on the phenomenon in Portugal. Then, we address the relationship between populist attitudes and personality traits, from which our hypotheses are derived. The third section sets out the methodological approach and the operationalisation of the key variables. The fourth section presents and discusses the results. The article ends with some concluding remarks and future research avenues.

Populism and Portugal

The concept of populism has certainly received a lot of mileage in public debates, fuelled by the fueled by the rise of radical right movements and parties worldwide. Claiming to represent a silent/pure/virtuous/homogeneous people, populists profess to lead an attack on conventional parties, institutions, academics, and the media (Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove, 2014; Canovan, 1999). The aim is to advance the idea that the people’s problems are easy to solve but persist due to the elites’ lack of action. It is from this presumption that arises the will to elect a charismatic leader, who can clearly communicate the popular discontent and put in check all those who ignore the daily hardships of the unrepresented people (Canovan, 1999).

Moffitt (2016) notes that populism can be viewed as a set of ideas, as a type of political strategy to gather support quickly, or as a type of discourse. Here we adopt the ideational definition of populism, described by Mudde (2004, p. 543) as an: “ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people”. Although not consensual, this definition is widely used because it is clear and minimalist, allowing the phenomenon to be explained without neglecting its scope.

The empirical literature which aims to identify individuals with populist attitudes, i.e. the demand-side of the phenomenon, has highlighted noteworthy associations between such proclivities and other socio-political attitudinal dimensions. For instance, Spruyt, Keppens and van Droogenbroeck (2016) found that populist support is associated with economic, cultural, and political vulnerability, emphasising the role of political efficacy perceptions. Elchardus and Spruyt (2016) link populist attitudes to a belief in social decline, often observed in citizens with economic disadvantages and lower happiness levels. Kaltwasser and van Hauwaert (2020) analysed the sociodemographic and political profiles of citizens in Europe and Latin America. In Europe, populist citizens tend to be interested in politics and disapprove of political parties. In Latin America, they are typically older, male, and unemployed. However, both groups share dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy. Demand-side research also explores factors such as citizens’ emotions (Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza, 2017), voting intentions (Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020), media preferences (Hameleers, Bos and Vreese., 2017), and personality traits (Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher, 2016; Fatke, 2019) to explain populist attitudes.

Portugal presents itself as an interesting case for studying populism from a demand-side perspective. For a long time, Portugal was considered an exception, as it went without populist representation for much longer than most European countries (Giorgi and Cancela, 2021). This particularity is explained by a set of factors, such as the legacy of the Estado Novo (Salgado, 2019), and the important role played by the radical left in channelling popular discontent in moments of economic crisis (Giorgi and Cancela, 2021; Lisi and Borghetto, 2018) - which, as some have pointed out, often took on a populist framing (Gómez-Reino Cachafeiro and Plaza-Colodro, 2018). However, in October 2019, the radical-right populist party, Chega (CH) managed to elect its first parliamentarian, and, in 2022, the party rose to become the third largest in parliament with 12 MP. This trend continued, and by 2024, the party’s influence had expanded further, reaching 50 MP, effectively putting an end to Portuguese exceptionalism. Even if without supply, Santana-Pereira and Cancela (2020) noted that the Portuguese already supported populist attitudes, particularly among those who intended to vote for parties with more radical left-right positions. However, the authors found no sociodemographic patterns associated with the different degrees of agreement with populist ideas.

Individual determinants of populist attitudes

This research looks at the demand-side of populism by characterising the individuals who support it in Portugal. With this in mind, we introduce the personality of citizens, their political efficacy, and other variables already studied in Portugal, such as party identification and sociodemographic characteristics, into the debate.

To study the relationship between citizens’ personalities and their adherence to populist ideas, we employ the Big Five Personality Traits model, which aggregates the various personality traits into five basic dimensions: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. The Big Five model has received criticism for its attempt to classify people using a system that tries to condense complex qualities into five simple categories (Caprara and Zimbardo, 2004). The model, however, uses characteristics that develop from childhood and tend to be stable over time - even if such stability might be contested in most recent accounts (Fasching, Arceneaux and Bakker, 2023) - making it particularly well suited to the study of political attitudes (Mondak and Halperin, 2008).

So far, the use of the Big Five model has produced mixed results often associated with how personality traits and populist attitudes manifest themselves differently depending on context (Fatke, 2019). Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher (2016) used the model to explain levels of support for populist parties/ideas and concluded that there is a strong relationship between low agreeableness and support for populism in the United States, Germany and the Netherlands. The study also shows that individuals who vote for populists do not necessarily have an authoritarian personality, nor do they do so in the form of irrational protest, meaning that to better explain populist voting, the personality of the individual in question must be taken into account. In turn, Fatke (2019) employed the model in the UK and Germany and found that personality traits manifest themselves in diverse ways in different contexts - whereas in the UK only openness appears to be related to more populist attitudes, in Germany such attitudes are related to higher degrees of conscientiousness and extroversion. This stresses the importance of cross-national analysis and warns of the danger of generalising conclusions when studying populist attitudes (Erisen, 2021).

Openness to experience is associated with creativity and imagination (Mondak and Halperin, 2008), and steers individuals away from conservatism and dogmatism (Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher, 2016). This makes them less likely to concur with the populist anti-elitist and Manichean views of society, which rely on the dogmatic notions that it is separated into two groups and that the people are being manipulated by a corrupt elite. Furthermore, this trait is associated with higher levels of self-confidence (Fatke, 2019) and internal political efficacy - the belief that one is competent enough to understand the political system and participate effectively in politics (Balch, 1974). This can translate into a lower tendency to agree with people-centred views, as we expect critical and politically active citizens to disagree with the idea that professional politicians should not make decisions for them. That said, openness characterises curious, politically interested individuals, who embrace change rather than perceiving it as a risk (Fatke, 2019). Therefore, we propose the first hypothesis:

H1: Individuals with lower levels of openness tend to exhibit more populist attitudes.

Conscientiousness relates to organised and hardworking individuals (Mondak and Halperin, 2008), who value responsibility and have a strong sense of duty (Pruysers, 2021) - which can translate into support for a people-centric view, especially if one believes the political elite to be incompetent or corrupt. Individuals with higher levels of this trait have a leaning towards risk aversion and status quo maintenance (Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher, 2016; Mondak and Halperin, 2008). For this reason, Gallego and Pardos-Prado (2014) hypothesised that conscientious individuals are more likely to criticise those who call into question the unity of the people, such as immigrants. Furthermore, these individuals tend to follow the anti-elitist idea that the people are being manipulated by elites (Pruysers, 2021). Conscientiousness is thus associated with a call for higher levels of scrutiny of representatives (Landwehr and Steiner, 2017). Along with the tendency to highly value the unity and virtuosity of the people, these types of conspiratorial beliefs align with a Manichean view of society. Finally, more conscientious individuals tend to have lower political efficacy and thus are more likely to base their political ideas on dogmas (Mondak and Halperin, 2008). Thus, we expect conscientiousness to be positively associated with populist attitudes:

H2: Individuals with higher levels of conscientiousness tend to exhibit more populist attitudes.

Extroverts are socially active and assertive (Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher 2016; Fatke, 2019), with a potential link to high internal political efficacy (Mondak and Halperin, 2008) through active participation in social initiatives. These individuals like to lead, value communication and prefer to work in cooperative networks (Mondak and Halperin, 2008). We expect this trait to be associated with a lower acceptance of a Manichean worldview, given that extroverts are socially very active, and therefore less likely to feel that society is profoundly divided. Furthermore, their social activeness and political interest point to a lower tendency to accept the idea that elites are manipulating the people. When considering populism’s focus on people-centric ideals, one might contend that extroverts are inclined to endorse professional politicians due to their perceived leadership capabilities. Nevertheless, extroverts may also exhibit a reluctance to accept decisions made by others. Therefore, we posit that:

H3: Individuals with lower levels of extraversion tend to exhibit more populist attitudes.

Agreeableness is associated with higher social trust, friendliness, and altruism (Mondak and Halperin, 2008). For this reason, this trait is deeply related to how individuals interact with others (Fatke, 2019). This leads us to expect that agreeable individuals are less likely to reject representative mechanisms, as this refusal is heavily based on a distrust of political actors.

Furthermore, the tolerant, cooperative, and understanding traits (Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher, 2016) associated with agreeable individuals are incongruent with the deep distrust of elites and the Manichean societal beliefs often found in anti-elitism. Agreeable individuals typically demonstrate generosity and empathy towards others (Nettle and Liddle, 2008), thereby making them less prone to adopting populist viewpoints. This is concurrent with the findings that citizens with lower agreeableness tend to be inclined to back populist parties and to be receptive to their messages (Fatke, 2019; Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher, 2016). High levels of agreeableness are also anticipated to result in less openness to an anti-establishment message and might even forecast support for populist parties. Conversely, less agreeable individuals tend to be more sceptical and therefore more receptive to populist messaging (Fatke, 2019). That said, we posit the following hypothesis:

H4: Individuals with lower levels of agreeableness tend to exhibit more populist attitudes.

Finally, more neurotic individuals tend to be more self-conscious, and to experience higher levels of depression and anger (Bakker, Rooduijn, and Schumacher, 2016; Fatke, 2019). While the relationship between neuroticism and populism is not evident, this personality trait stands out in citizens who tend to consider that society is unfair or unsatisfactory (Mondak and Halperin, 2008). This tells us that these citizens may be less inclined to trust political representatives (people-centrism), which can result in a higher susceptibility to populist messages portraying people as victims of the elite. Once these beliefs are set, it is expected that neurotic individuals are far more likely to adhere to Manichean views. This, in turn, can lead to increased political support for populist attitudes, given that anger and discontentment are both products and fuels of populism (Ric, Guinjoan and Anduiza., 2017; Spruyt, Keppens and Droogenbrieck, 2016). The following hypothesis can, thus, be derived:

H5: Individuals with higher levels of neuroticism tend to exhibit more populist attitudes.

Populist attitudes may also be dependent on political efficacy, defined as the individual’s feeling that political action can and does have an impact (Campbell, Gurin and Miller, 1954). Citizens who are confident in their ability to interpret and intervene in politics tend to be more satisfied with the overall polity, and to participate more (Balch, 1974). As engaged individuals, they resist the populist call for radical changes as they are less dissatisfied with leaders. In contrast, those with low political interest tend to support populism more (Spruyt, Keppens and Droogenbrieck, 2016). Therefore, people with lower political efficacy are likely to embrace populist attitudes, being more open to the idea of a strong leader representing them.

We also account for party identification and its connection with populist attitudes. Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser (2019) argue that party identification should be treated as the proximity to a party that offers a political map to voters, thus influencing their preferences and positions. While CH is often recognized as the only clearly populist party (Mendes, 2021), others also make use of populist rhetoric, albeit to a lesser degree, such as the Left Bloc (Bloco de Esquerda, BE) and the Portuguese Communist Party (Partido Comunista Português, PCP) (Lisi and Borghetto, 2018; Salgado, 2019). Our analysis delves into the influence of party identification on populist attitudes, acknowledging the potential reciprocal relationship between these dimensions. Individuals may align themselves with a party that mirrors their existing populist beliefs, and vice versa. Indeed, Santana-Pereira and Cancela (2020) noted that certain Portuguese citizens displayed populist attitudes even before the emergence of a successful fully-fledged populist party. It is anticipated that identification with any of these parties may further strengthen populist attitudes.

The last group of control variables refers to the sociodemographic characteristics as determinants of populist support. Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza (2017) demonstrate that populist attitudes may stem from discontentment with one’s personal situation, i. e., individuals who consider themselves to be less benefited by the current social arrangement. The unemployed, for instance, may be more susceptible to populism (Rovira Kaltwasser and van Hauwaert, 2020; Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020). We also expect citizens to be more permeable towards populism when they are male (Elchardus and Spruyt, 2016; Rovira Kaltwasser and van Hauwaert, 2020); older (Rovira Kaltwasser and van Hauwaert, 2020; Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020), and less educated (Elchardus and Spruyt, 2016; Rovira Kaltwasser and van Hauwaert, 2020; Spruyt, Keppens and van Droogenbroeck, 2016).

Data and methodology

The data used in this study was collected from a sample of the Portuguese population, between February and March 2021. At the time of the data collection, the country had just re-elected Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa to his second term as President. André Ventura, the founder of CH and its sole parliamentarian at the time, secured third place in those elections. Despite his recent rise as a populist figure in Portugal, his popularity had been steadily increasing.

The sample used in this study consists of a total of 1510 participants. The survey was conducted online, with respondents being able to use a wide diversity of devices to access (mobile, 44.8%; desktop, 53%; or tablets, 2.5%).2 Of these, 52% are female and 48% are male. The average age is 41 years old, varying between 18 and 65. Participants are divided into five age groups: 18-24 (16%), 25-34 (16%), 35-44 (24%), 45-54 (23%) and 55-65 (21%). Regarding professional occupations, most respondents (73%) are active workers, and the remaining are divided into students (10%), unemployed (12%) and retired (5%). Regarding education, the sample is divided into three groups: up to secondary school (11%), with secondary education (29%), and respondents who are attending (or have completed) higher education (60%). The sample includes citizens from the North (36.4%), Lisbon (27.6%), Centre (23.8%), Algarve (7.5%), and Alentejo (4.6%). Finally, most respondents voted both in the 2019 parliamentary elections (78%) and in the 2019 European elections (68%).

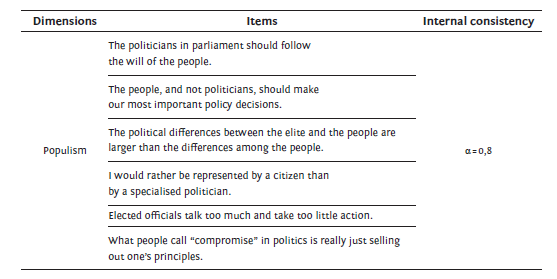

We chose Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove’s (2014) scale to measure the respondents’ populist attitudes, following previous demand-side studies in Portugal (see Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020). It consists of a group of six items that measure the degree of agreement with six different statements (on a 5-value Likert-type scale), included in Table 1. This widely used scale presents considerable internal consistency, cross-country validity, conceptual breadth, and external validity (Castanho Silva et al. 2020). The six statements have their scores added together, meaning that the scale can vary between 6 and 30, with higher scores showing a greater likelihood of representing populist attitudes. In our research, it depicts a high internal consistency (α = 0.8).

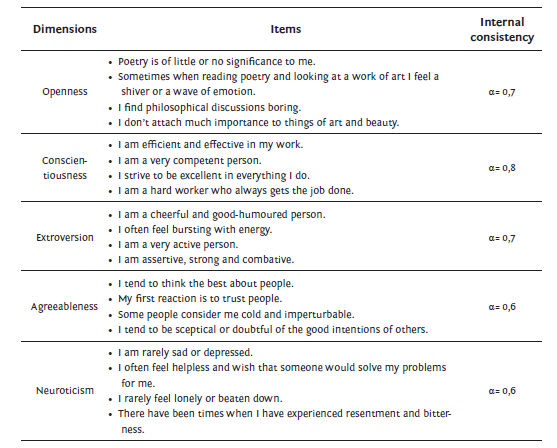

Measurement of personality traits derives from the Personality Inventory NEO-FFI-20 (Bertoquini and Pais-Ribeiro, 2006). Twenty items (Table 2) were rated by the respondents using a 5-value Likert-type. Each participant can have between 5 and 20 points in each of the personality traits, and the higher the score, the greater the presence of that trait in the individual’s personality (Bertoquini and Pais-Ribeiro, 2006). As depicted in Table 2, we found solid levels of internal consistency across all traits.

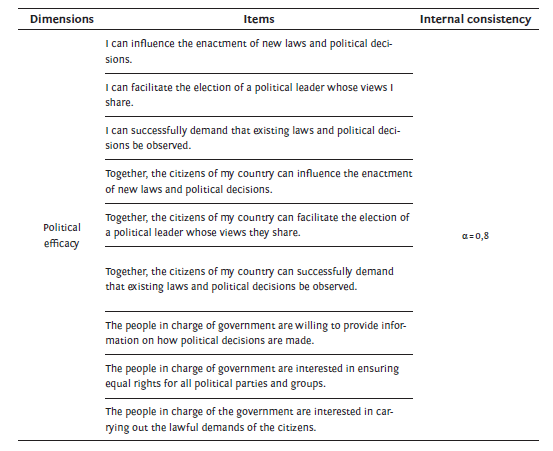

Political efficacy was measured by adapting the Political Effectiveness Scale (Sarieva, 2018). To obtain a score, respondents reveal their level of agreement with each of the nine items presented in Table 3 - through a five-point scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (5). When applied to this study, the scale showed a high degree of internal consistency (α = 0.8).

Results and discussion

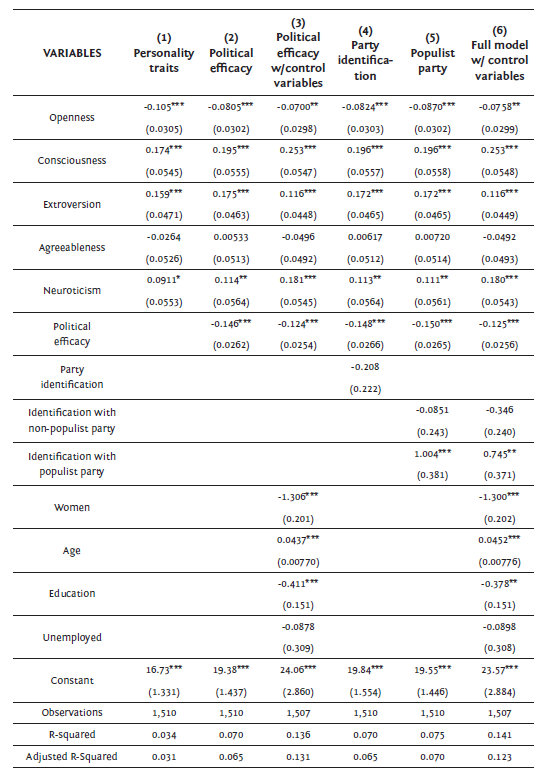

This research seeks to explain populist attitudes and to do that, six linear regression models were estimated. The first isolates the effects of personality traits. The second model introduces political efficacy as a control variable and Model 3 estimates this effect when controlling for sociodemographic features. Models 4 and 5 study the effect of party identification, with Model 5 reporting the effect of respondents’ identification with parties with populist rhetoric. Finally, the sixth represents the full model, controlling for sociodemographic variables. All the models can be found in Table 4.

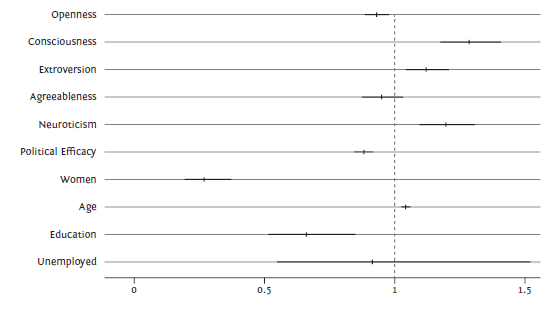

Figure 1 depicts the results of the linear regression analyses for Model 1. Regression coefficients are plotted, along with the estimates for each effect in the model, with lines that indicate the width of 95% confidence intervals. When the confidence intervals intersect the reference line at 0, these are not statistically significant predictors of populist attitudes.

Figure 1 Personality traits and composite score of populist attitudes. Note: Coefficients (with robust standard errors) and confidence intervals from regression models in Table 4 (Model 1).

Using the standard α = 0.001 cutoff, three (of the five) personality traits emerge as significant predictors of citizens’ populist attitudes. Regarding openness, the results point to a negative relationship between it and populist attitudes. This is in line with the German case, where a negative relationship between openness and populist voting was found (Bakker, Rooduin and Schumacher, 2016). The results suggest that citizens who are more accepting of change and more receptive to new ideas have a lower degree of populist attitudes, as posited in H1.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis (H3), our findings reveal that extroverts are actually more predisposed to embrace populist attitudes compared to introverts. This outcome contrasts with previous research associating extroversion with populist voting behaviours observed in the USA, the Netherlands, and Germany (Bakker, Rooduin and Schumacher, 2016). Portugal presents a distinct pattern, where individuals who are more participative and vocal in expressing their opinions tend to align more closely with populist ideals. This unexpected finding underscores the complexity of populist attitudes and the nuanced ways they manifest across different cultural and political contexts.

As expected, conscientiousness emerges as a statistically significant predictor of populist attitudes, as per H2. More conscious individuals tend to be more swayed by populist messages when compared to citizens who score lower on this trait. These individuals are prone to agree with the idea that they are being tricked by powerful elites who control all main decisions (Pruysers, 2021). Their higher conscientiousness score can lead to the expectation that everyone should behave as responsibly as they do - which translates into favouring strongly regulated systems, with severe punishments for offenders, as often advocated by populist parties. Conscientious individuals often expect rewards for their good behaviour (Pruysers, 2021) and may also feel left behind. They tend to avoid new experiences, favour conservatism, and exhibit low political efficacy (Landwehr and Steiner, 2017). This inclination contributes to their attraction to the simplicity of populist solutions grounded in speedy implementation and charismatic leadership.

Populist attitudes also find a fertile ground amongst individuals with high neuroticism scores - even if we consider a less conservative threshold to estimate the significance of the variable in the model. In other words, more neurotic individuals tend to hold more populist attitudes, as postulated in H5, largely due to their tendency to experience negative feelings like anger.

Against our expectations (H4), agreeableness does not emerge as significant in explaining populist attitudes. This trait does not seem to hold relevance across Portuguese citizens, suggesting a potential interplay between personality traits and cultural and historical factors. This becomes even more apparent when considering comparative studies that emphasise the significance of agreeableness, particularly in long-established democracies ( Ackermann, Zampieri and Freitag, 2018; Bakker, Rooduijn and Schumacher, 2016). In the Portuguese context, there appears to be no significant association between a cooperative, kind, and altruistic personality and populist attitudes.

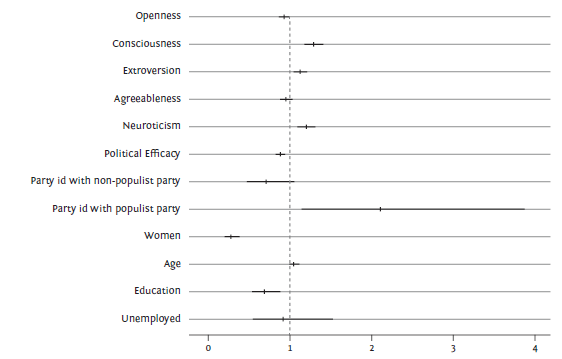

Overall, when considering the relevance of personality traits, it can be argued that the feelings of threat, uncertainty and anger are the main drivers of populist attitudes, and these feelings may be ingrained in personality traits. Furthermore, low levels of openness to new experiences can also play a role in fostering populist attitudes, as less open individuals may be more resistant to change and more inclined towards traditional, populist narratives. These results hold even when we account for political efficacy and demographic controls (Figure 2). As depicted in Model 3, populist attitudes tend to be more prevalent among individuals with lower political efficacy thus confirming extant research (Rooduijn, van der Brug and Lange, 2016).

As anticipated, individuals with lower levels of political efficacy demonstrate a greater propensity to endorse populist attitudes, which may reflect the anti-elitist aspect inherent in populism. Political efficacy indicates the belief that citizens can influence the political process. In Portugal, those who harbour doubts about their ability to effect change within the political sphere are more inclined to support populism. This suggests that feelings of disenfranchisement or disempowerment play a significant role in driving populist sentiments among the populace.

Models 4 and 5 consider the association between party identification and populist attitudes. As depicted in Model 4, identifying with a political party is not a predictor of populist attitudes. Individual’s proximity to a specific party does not seem to influence their tendency to develop populist attitudes. Nonetheless, not all parties are equal. Indeed, the identification with parties3 with populist stances may generate more permeability towards populist messages, as reported in Model 5. These results hold even when we control for sociodemographic features, in Model 6.

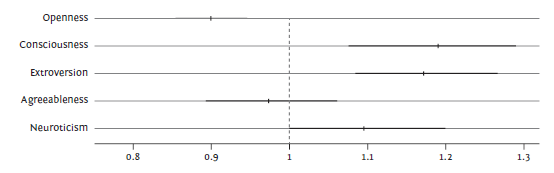

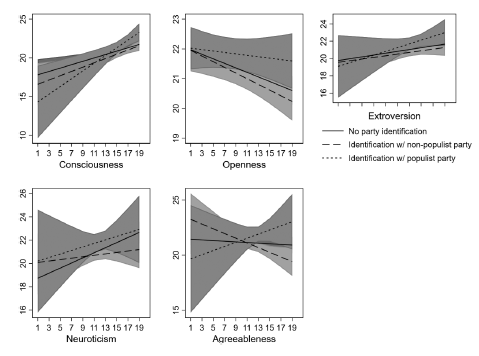

It is also relevant that only two personality traits interact with party identification: conscientiousness and openness. We expect that citizens who feel close to parties with populist discourses may reinforce their preferences and positions based on the set of ideas put forward by these parties. To address this, we separately estimated the interaction between self-reported identification with populist parties and each of the Big Five personality traits, when accounting for all the variables depicted in Model 6. Figure 4 illustrates these interactions by plotting the marginal effects. The first significant interaction identified, using a higher threshold, pertains to the interaction between party identification and conscientiousness (B = .280,p = <.095). As depicted, there is a cross-over interaction, even if with a large overlap in confidence intervals, particularly when citizens display low levels of conscientiousness. However, following and identifying with a populist party emerges as a relevant moderator for the relationship with populist attitudes. Indeed, consciousness emerges as a personality trait that is particularly relevant to explaining the populist attitudes of citizens who identify with populist parties. These results echo extant research on the effect of this trait. Landwehr and Steiner (2017) suggest that conscientious individuals, characterised by thoroughness and being well-informed, may lean towards scrutinising elected representatives and harbouring potential anti-elitist sentiments (Pruysers, 2021). Also, Federico and Aguilera (2019) reported that conscientious individuals tend to be more conservative and critical towards threats to the unity of the people in general.

Overall, we can say that individuals who cultivate a strong sense of work and responsibility, and who advocate for harsher punishments for lawbreakers, have more populist attitudes, particularly if these are reinforced by the identification with a populist party. From these results, we can argue that the Portuguese who are more conscientious, tend to go about their lives in a very steady manner, hoping that their hard work does not go under the radar. In such instances, they may arguably gravitate towards populist solutions, which provide them with an opportunity to gain visibility, often not for the purpose of advocating significant changes, but rather to critique those whom they perceive as receiving a disproportionate share of political attention. Therefore, while we anticipate individuals with high conscientiousness to be more receptive to populist messages (as per the aforementioned models), it is important to recognise the reciprocal nature of the relationship between party identification with populist parties and populist attitudes. This suggests that conscientious individuals are more likely to strengthen their populist positions when aligning with and identifying with a populist party, and conversely, individuals with pre-existing populist attitudes may be more inclined to identify with populist parties.

Figure 4 Predicted probability of populist attitudes for different personality traits and identification with populist parties

Party identification also interacts with openness. In this case, however, the coefficient B = -0.095 and the associated p-value of p < 0.003 represent the effect size and significance level, respectively, for one level of the interaction between the level of openness and the identification with non-populist parties. This suggests that, at this particular stage of our ordinal variable, the effect of openness on the outcome, populist attitudes, is statistically significant. Importantly, this effect is not observed among individuals who identify with populist parties. Hence, openness does steer individuals away from conservative and dogmatic ideologies (Bakker, Rooduijn and Schumacher, 2016), rendering them less inclined to resonate with populist attitudes. This tendency is notably pronounced among individuals who do not identify with populist parties.

Lastly, it’s worth noting that the three most influential factors are gender, age and education. This aligns with prior research suggesting that male citizens tend to exhibit a higher propensity for populism (see, for example, Rovira Kaltwasser and van Hauwaert, 2020) and the latter also corroborates with extant research on the effect of age (Rovira Kaltwasser and van Hauwaert, 2020; Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020). These findings confirm the theory that populism has a stronger impact on individuals who perceive dissatisfaction with their current social status, particularly among those with low levels of education. In Portugal, this means that older male citizens tend to have more populist attitudes because they perceive that their social position is somehow under threat from the recent changes to the social paradigm.

Conclusions

This article suggests that personality traits play a significant role in shaping political attitudes and behaviour, and that these are important factors in explaining the populist attitudes of the Portuguese. Results enable us to reasonably delineate the traits of the Portuguese population that exhibit receptivity to populist messages.

These individuals tend to have low levels of openness and high levels of conscientiousness. The fact that they are more conscientious reflects their hard-working nature and deep sense of responsibility, which translates into favouring strongly regulated systems, with severe punishments for offenders - issues frequently addressed by populists. Furthermore, the prominence of consciousness and neuroticism makes these individuals more prone to feelings of anti-elitism (distrusting the elite and with a tendency towards deep feelings of fear and anxiety that often lead to conspiratorial reasoning).

Those more receptive to populist messages also tend to be averse to new experiences (low openness), basing their opinions on dogmas and conservatism, and very grim about the idea of their work/efforts going unnoticed and unappreciated (high consciousness). Results also suggest that following and identifying with parties with populist rhetoric may intensify populist attitudes, particularly amongst conscientious individuals. Lastly, in terms of sociodemographics, these individuals typically lean towards being older and male, and they tend to possess less formal education.

This set of characteristics reveals that these citizens seek political participation to mitigate perceived risks. This often leads to a preference for quick, simple solutions over complex problem-solving. They prioritise swift issue resolution to feel safer, even if it means overlooking potential harm to others - which often results in the advocation of conservative solutions instead of innovative ones, given their low openness. Moreover, conscientious citizens tend to defend the notion of the unity of the people, being leery of everything that has the potential to disrupt the status quo - such as immigrants. These results suggest that populist individuals, when feeling unsafe in their daily lives, actively promote stricter rules, driven by a fear of social status loss and a desire for maximum control to enhance their sense of security.

This study also underscores that political efficacy plays a pivotal role in assessing the populist attitudes of Portuguese citizens. Populist individuals often lack confidence in their political influence, feeling misrepresented and disconnected from decision-making. Hence, a strategy to alleviate populist tendencies among voters could involve making decision-making more accessible and responsive to citizen demands through political reforms and improved public services.

What do the results say about Portuguese exceptionalism? We believe they corroborate Santana-Pereira and Cancela’s (2020) argument that the issue lies more in the lack of political representation than a lack of demand. People with this set of traits have always existed in the country but were politically homeless. However, the arrival of a credible populist party in 2019, with a discourse based on law and order, anti-corruption, and welfare parasitism, often connected to racialised minorities (Mendes, 2021), provided them with the political home they sought. Indeed, when we look at the results of the regression models, we find that variables such as populist party identification offer more solid ground in explaining populist support.

We believe that future research can benefit from an improvement in the scale used to measure populism, considering the multidimensional and non-compensatory nature of the concept (as per Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen, 2020). Moreover, research that focuses on individual determinants of populist attitudes could benefit from medium- and long-term monitoring, to understand the effect of political instability on the personalities and populist attitudes of citizens.