Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.112 Lisboa dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis17809

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Migrant welfare tactics and transnational social protection between Portugal and the UK

Táticas de bem-estar dos migrantes e Proteção social transnacional entre Portugal e o Reino Unido

Tactique du bien-être des migrants et protection sociale transnationale entre le Portugal et le Royaume-Uni

Tácticas de bienestar de los migrantes y protección social transnacional entre Portugal y el Reino Unido

Bruno Machado1, Jennifer McGarrigle2, Maria Lucinda Fonseca3, Alina Esteves2

1 Associate Researcher, Centro de Estudos Geográficos, Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território, Universidade de Lisboa, Rua Branca Edmée Marques, 1600-276, Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: bmachado@campus.ul.pt

2 Professor and Effective Researcher, Centro de Estudos Geográficos, Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: jcarvalho@campus.ul.pt, alinaesteves@campus.ul.pt

3 Full Professor and Effective Researcher, Centro de Estudos Geográficos, Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: fonseca-maria@campus.ul.pt

ABSTRACT

Migration and the sustainability of the welfare state are irrefutably two essential topics in the political debate throughout Europe. Not only has the dominant pattern within the political discourse been focused on the generosity of benefits attracting migrants as, until recently, researchers tended to concentrate on the supposed “weight” of migration on destination countries. This view contrasts with new perspectives that highlight not only the levels of unawareness regarding benefits or social services in the destination countries as well as transnational practices involving a myriad of formal and informal providers across borders. Drawing on qualitative data gathered through 39 interviews conducted with British migrants in Portugal and Portuguese migrants in the UK, we explore migrants’ welfare experiences. Deploying the idea of social protection assemblages, which is the combination of formal and informal elements of protection, the analysis explores the welfare tactics that migrants adopt across transnational space to ensure their social welfare needs are met in the present and future. Local social capital, social networks and the process of welfare learning are key aspects in navigating the welfare system in the destination. Simultaneously, transnational practices are employed to overcome the gaps in formal services, either by piecing two formal social protection systems or informal elements provided by interpersonal networks. We demonstrate the importance of happenstance and “just in case” practices as well as cultural values and other non-economic factors as bearing a deep impact on how migrants ‘do’ social protection.

Keywords: Intra-EU mobility; social protection; transnationalism; arrangements welfare; strategies.

RESUMO

As migrações e a sustentabilidade do Estado-Providência constituem, indubitavelmente, dois tópicos centrais do debate político em toda a Europa. Além de o padrão dominante do discurso político se ter focado na generosidade dos benefícios sociais como fator de atração para os imigrantes, até recentemente, os investigadores têm privilegiado a análise do suposto “peso” das migrações para os países de destino. Esta visão contrasta com novas perspetivas que sublinham não apenas os níveis de desconhecimento dos benefí cios sociais e serviços públicos existentes nos países de destino, assim como as práticas transnacionais que envolvem uma miríade de atores formais e informais, que prestam assistência al ém-fronteiras. Através de 39 entrevistas com migrantes britânicos em Portugal e migrantes portugueses no Reino Unido, exploramos as suas experiências com a proteção social. Analisando a no ção de “assemblagens” de proteção social, consistindo numa combinação entre elementos formais e informais de proteção, a nossa análise procura compreender as táticas relacionadas com o bem-estar adotadas pelos migrantes de forma transnacional com o objetivo de garantir que as suas necessidades, neste contexto, sejam garantidas no presente e futuro. O capital social local, as redes e o processo de “welfare learning” são aspetos fundamentais para lidar com o sistema de proteção social no destino. Simultaneamente, práticas transnacionais s ão desenvolvidas com o objetivo de ultrapassar as falhas existentes nos serviços formais, quer através da combinação de dois sistemas de proteção social, como através de elementos informais providenciados por redes pessoais. Demonstramos aqui a importância de elementos como o “acaso” ou práticas preventivas, assim como dos valores culturais e outros fatores não económicos que detêm um profundo impacto na forma como os migrantes ‘fazem’ a sua proteção social.

Palavras-chave: Mobilidade intra-europeia; proteção social; transnacionalismo; “pacotes” de proteção social; estratégias.

RÉSUMÉ

Les migrations et le développement durable de l’état-providence sont, sans doute, deux thèmes centraux du débat politique dans toute l’Europe. Non seulement le modèle dominant du discours politique a mis l’accent sur la générosité des prestations sociales comme un facteur d’attraction pour les migrants, bien comme jusqu'à récemment, les chercheurs se sont concentrés sur l’analyse du « poids » supposé des migrations vers le pays de destination. Ce point de vue contraste avec les nouvelles perspectives qui soulignent non seulement les niveaux d ’ignorance des avantages sociaux et des services publics existants dans le pays de destination, ainsi que les pratiques transnationales qui impliquent une myriade d’acteurs formels et informels, qui fournissent une assistance transfrontalière. Lors de 39 entretiens avec des migrants britanniques au Portugal et des migrants portugais dans le Royaume-Uni, nous avons exploré leurs expériences avec la protection sociale. Explorant la notion « d’assemblées » de protection sociale, consistant d’une combinaison d’éléments de protection formels et informels, nôtre analyse cherche à comprendre les tactiques liées au bien-être adoptées par les migrants de manière transnationale afin d’assurer que leurs besoins, dans ce contexte, sont satisfaits pour le pré sent et l’avenir. Le capital social local, les réseaux et le processus de « welfare learning » sont des aspects essentiels pour faire face au système protection sociale du pays de destination. En même temps, les pratiques transnationales sont développées avec le but de surmonter les lacunes des services formels, soit par la combinaison de deux systèmes de protection sociale, soit à travers des éléments informels fournis par des réseaux personnels. Nous démontrons ici l’importance d’éléments tels que le «hasard» ou les pratiques préventives, ainsi que les valeurs culturelles et d’autres facteurs non économiques ayant un impact profond sur la manière dont les migrants «font» leur protection sociale.

Mots clés: Mobilité intra-européenne; protection sociale; transnationalisme; «paquets» de protection sociale; stratégies.

RESUMEN

La migración y la sustentabilidad del estado del bienestar son, sin duda, uno de los temas centrales del debate político en toda Europa. Además, el padrón dominante del discurso político se he centrado en generosidad social de los beneficios como factor de atracción para los inmigrantes, hasta hace poco, los investigadores han privilegiado el análisis del "peso" de la migración a los paí ses de destino. Esta visión contrasta con nuevas perspectivas que enfatizan no sólo los niveles de desconocimiento de prestaciones sociales y servicios públicos existentes en los países de destino, as í como las prácticas transnacionales que involucran a un sin número de actores formales e informales, la asistencia transfronteriza. A través de entrevistas con 39 inmigrantes británicos en Portugal y los inmigrantes portugueses en el Reino Unido, exploramos sus experiencias con la protección social. Explorando la noción de “ensablajes” de protección social, consistente en una combinación entre elementos formales e informales de protección, nuestro análisis busca comprender las tácticas relacionadas con el bien-ser adoptadas por los migrantes de forma transnacional con el fin de garantizar que sus necesidades en este contexto estén garantizadas en el presente y en el futuro. El capital social local, las redes y el proceso de “welfare learning” son aspectos fundamentales para hacer frente al sistema de protección social en el destino. Al mismo tiempo, se desarrollan prácticas transnacionales con el fin de superar las deficiencias existentes en los servicios formales, bien mediante la combinación de dos sistemas de protección social a través de elementos informales proporcionados por redes personales. Demostramos aquí la importancia de elementos como el “acaso” o pr ácticas preventivas, así como de los valores culturales y otros factores no económicos que tienen un profundo impacto en la forma en que los migrantes ‘hacen’ su protección social.

Palabras clave: Movilidad intraeuropea; protección social; transnacionalismo; "paquetes" de la protección social; estrategias.

I. INTRODUCTION

European mobility for some is a ‘taken for granted reality’, however, as Trenz and Triandafyllidou (2017, p. 551) point out it has more recently become a ‘contested field’ seen to the extreme in Brexit. The idea of benefit tourists and undeserving intra-EU migrants was a key feature of the political and public rhetoric of the leave campaign leading up to the Brexit referendum. In this context, the connections between migration and welfare have come under increasing scrutiny. Based on a qualitative study, this paper contributes to the growing literature on complex intra-EU mobility experiences by focusing on two contrasting flows – Portuguese migrants in the UK and British migrants in Portugal. On the one hand, the former reflects unevenness in European labour markets exacerbated after the economic crisis and austerity in Portugal (Bartolini, Gropas, & Triandafyllidou, 2017). On the other, North-South lifestyle migration from the UK to Portugal presents a counter stream of migrants in search of a better quality of life at a lower cost (King, Warnes, & Williams, 2000; Torkington, 2012; Sardinha, 2013).

The EU’s transnational framework to enable intra-EU migrants to port their social protection among member states has been the focus of much discussion and, in regulatory terms, cited as a “best-practice example ” (Scheibelhofer & Holzinger 2018, p. 201). However, to understand how this regulatory system works in practice, in this paper, we explore the welfare experiences and tactics of intra-EU citizens during mobility. Borrowing from De Certeau (1984), we use the term tactics, relating to migrants’ routines of everyday practice acting within the more powerful strategies defined by institutions or organized bodies. Through the comparison of two case studies with different welfare regimes, we demonstrate how difficulties in understanding regulations as well as different cultural and institutional practices can limit the access of migrants to welfare and impact levels of satisfaction. In response, we explore how migrants learn and respond to the limits of the system through the construction of welfare assemblages across different sectors and nation states.

Our analysis draws upon recent scholarship on transnational social protection, which provides an analytical and theoretical framework to move beyond the coupling of welfare and nation and to embrace new forms of transnational living and strategies of social protection. As such, we adopt a broad definition of welfare, including formal and informal providers across borders (Tiwari, 2011; Faist, Bilecen, Barglowski, & Sienkiewicz 2015; Faist, 2017; Levitt, Viterna, Mueller, & Lloyd, 2017). In order to explore these aspects, we interviewed migrants at different stages in the life cycle. Yet, while we take a life course approach, we frame it more broadly. In the words of Hockey and James (2003, p. 5), we conceive “the passage of a life time less as mechanical turning of the wheel and more as the unpredictable flow of [a] river”. The life course approach has been based on the idea of linearity, a programed sequence of events (Collins & Shubin, 2015, p. 96). However, as our empirical data demonstrates, there is also an element of “happenstance” in migrants’ lives.

The paper is structured as follows. In the first section, we focus on the debate regarding migration and social protection in the context of intra-EU migration. This is followed by an outline of the methodology and a brief description of the context. The empirical sections explore the strategies of social protection and experiences with portability, processes of welfare learning to access public services and transnational social protection strategies. Cross-cutting these sections we demonstrate the importance of cultural values and other emotional or non-economic factors as bearing a deep impact on how migrants ‘do’ social protection Finally, in the conclusion we argue that migration and social protection tactics are creative assemblages, strongly embedded in social networks, developed often in happenstance or ‘just in case’ in response to changing individual, institutional and political settings (Bilecen & Barglowski, 2015; Phillimore, Humphris, Klaas, & Knecht, 2016).

II. TOWARDS A TRANSNATIONAL UNDERSTANDING OF SOCIAL PROTECTION: BEYOND MAGNETS AND NATIONAL TYPOLOGIES

Studies developed on welfare and migration have, largely, crystalized around two main discourses and assumptions. First, they have focused on the theory of the state as a “welfare magnet” (Borjas, 1999; Razin & Sadka, 2000; Kvist 2004; Sinn 2004; Giulietti, 2014). This theory emphasizes the burden of migration flows on destination countries’ social security systems, constituting a host country bias. It also assumes that migrants have perfect information on benefits and public services available in the country of destination. However, as Ciobanu and Bolzman (2015, p. 10) argue, there is a degree of misinformation about the details of a given country’s benefits and/or social services. Second, the “deservingness” of migrant welfare beneficiaries echoes in current discourses surrounding migration and welfare. Migrants are often portrayed as the perpetrators of high levels of welfare take-up and dependency, a net drain to the system. However, some studies have argued to the contrary by showing that, in Portugal, migrant contributions are higher than benefit take up (Peixoto, Marçalo, & Tolentino, 2011). Similarly, comparing Germany and the UK, Bruzelius, Chase, and Seeleib-Kaiser (2016) found that the percentage of EU citizens claiming benefits is lower than that of national citizens.

The welfare state in the United Kingdom has been classified as liberal and can be described as a regime with a low level of decommodification, meaning that welfare depends on an individual’s market position. This changes somewhat when healthcare is brought into the analysis as the healthcare system shows high levels of decommodification in that is more redistributive or universal (Bambra, 2005). Outside this classification, we find the Mediterranean regime, a “familialistic” category, alluding to the central role of the family, shared by Greece, Portugal and Spain mainly due to the similarities in economic and socio-demographic aspects together with an authoritarian or dictatorial regime in their past. If, on the one hand, scholars have broadly applauded this typology, on the other hand it has been criticized (Arts & Gelissen, 2002; Bambra, 2007). Esping-Andersen (1990) refers to ideal-types of welfare states concurrently ignoring the actual delivery of services. Hence, this typology though constituting an important starting point for studying the welfare state should be viewed critically (Bambra, 2007, p. 1101). Indeed, as we demonstrate in this paper there is a need for scholars to look at welfare state related matters in a more holistic or all-inclusive way. Tiwari (2011, p. 5) calls it a “total view of the welfare system”, including social security, social protection and social safety nets. It is then crucial to move away from fixed notions of the welfare state and make room for analyses that contemplate migrants’ personal/informal practices and formal resources (Boccagni, 2011, p. 319). Moreover, relying on welfare state typologies necessarily produces a nation-state-based view of welfare provision. As migrants’ lives encompass wider social fields there is a need to look beyond the fixed analytical boundaries of the nation state.

Recent approaches have paved the way for this analytical shift. Authors like Levitt et al. (2017) along with Faist (2017) present us with the notion of “transnational social protection” which can be defined as “the policies, programmes, people, organizations, and institutions that provide for and protect individuals (…) in a transnational manner” (Levitt et al., 2017, p. 5). Furthermore, this approach calls our attention to different ways individuals operate and “piece together a package of protections from more than one nation-state, or how nation-states might protect and provide for a population on the move ” (Levitt et al., 2017, p. 4). Fixed analyses at the national level are questioned by these authors, underlining the need to excavate more than just migration flows and sets of benefits and effectively investigate the complex relationships that constitute the interplay between individuals and both formal and informal welfare state regimes (Bilecen & Sienkiewicz, 2015). As formal systems can be difficult to navigate, there is a need to rely on interpersonal networks and to build informal strategies (Ciobanu & Bolzman, 2015; Bilecen & Sienkiewicz, 2015; Ehata & Seeleib-Kaiser, 2017) and the combination of different resources creating complex assemblages (Phillimore, Humphris, Klaas, & Knecht, 2016).

III. METHODOLOGY AND CONTEXT

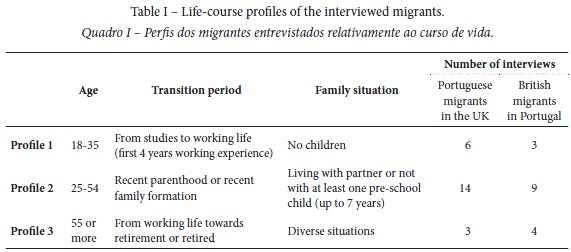

As previously mentioned, this paper draws on qualitative data gathered through 39 interviews conducted with British migrants in Portugal and Portuguese migrants in the UK. Based on different life course traits, we defined 3 main profiles with specific age limits, family situations and having experienced or expecting to experience specific life transitions (table I).

Interviews were conducted over spring and summer, in 2017, following snowball sampling both in person as well as through Skype. Interviews were transcribed fully before coding took place with NVivo. Our research focussed for the most part on the capital regions in each country, London in the case of the UK and the Lisbon Metropolitan Area in the case of Portugal. All names presented here are pseudonyms in order to maintain interviewee anonymity.

The British community has a long-standing presence in Portugal and has grown substantially in the last few years (SEF, 2019). UK citizens, unlike the other labour or post-colonial migrants can be described as lifestyle migrants (Torkington, 2012). Recent Portuguese policy has actively tried to attract intra-EU migrants through fiscal benefits or exemptions for non-habitual residents (Montezuma & McGarrigle, 2018). Besides the ancient trade relations that consolidated the presence of English wine producers in the Douro Valley and on the island of Madeira, British citizens have been living in the Lisbon region since the WWII and are one of the major communities settled in the Algarve (Cavaco, 2005; Moreno, 2007). In the capital region, where the interviews used in this paper were conducted, they mostly reside in Cascais, Estoril and Lisbon. At the national level, it is the 5th largest migrant group in the country, with 26 445 people (SEF, 2019). According to SEF (Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras) (non-published data), this group is characterised by a mix of professionals and retirees shown by age composition and income sources, with 38.1% of all documented British citizens in 2017 being 65 or older, whereas 52.0% are aged between 25 and 64. In addition, according to data from the 2011 Population Census, income from retirement pensions was the main source of funds for 41.1% of the British population aged 15 or above, while only 29.9% lived on income from work and 11.7% lived on family means.

According to estimates of the Observatory of Emigration, in 2017, there were 139 thousand Portuguese citizens residing in the United Kingdom, representing the 5th largest Portuguese community living in a foreign country (Pires, Pereira, Azevedo, Vidigal, & Moura Veiga, 2018). Although not a recent phenomenon, Portuguese migration to the UK gained relevance from the end of the 1990s onwards (Almeida & Corkill, 2010) and is presently the main destination for Portuguese migrants (Pires et al., 2018; Rocha, 2018). Looking into data from the Observatory of Emigration, since 2008, in the context of the long-lasting economic crisis, high levels of unemployment, labour market imbalances and the high social costs of austerity policies, the number of Portuguese citizens who entered the UK leapt from 12 980 in 2008 to 32 301 in 2015. Despite Portugal’s economic recovery since 2014i, only in 2016 was it possible to observe a slight reduction of the migratory flows to the UK (30 543). The United Kingdom is also the country that attracts most high-skilled Portuguese migrants (Góis, Marques, Candeias, Ferreira, & Ferro, 2016; Pires et al., 2018). However, despite general assumptions, Portuguese immigrants are among the least qualified, in educational terms, when compared to other immigrant groups, and are mostly employed in the distribution, hotel and restaurant sectors (Justino, 2016). Although dispersed across Great Britain, according to data from the 2011 Population Census, London is the region where more Portuguese-born residents live (46.6%), followed by the South East and the East of England, respectively with 14.25% and 13.8%. While the research contexts are distinct, in the following sections we will tease out, not only differences, but also similarities between the two nationality groups concerning individual tactics developed to navigate public services and social protection systems. In the following section, we turn to the question of portability to explore the interviewees’ experiences and future perceptions on porting pensions and social benefits.

IV. SOCIAL PROTECTION AND PORTABILITY: COMPLEXITY, TRUST AND “JUST IN CASE” SAFETY NETS

Regarding the European Union’s modus operandi, in theory, individuals are able to port their pensions and social benefits between EU member states (regulations EC 883/2004 and EC 987/2009). Indeed, in accordance with other studies (Carmel, Sojka, & Papiez, 2016), in general, porting contributory state pensions was a straightforward and linear process even when it included periods of work in more than one EU member state. Linda, a retired British migrant living in Portugal provides an example of this:

“It was brilliant, plain sailing. And they said, which countries have you worked in and they contacted the countries, they got a letter from England, they got a letter from Spain and started receiving from Portugal, England, Spain (…).” (British migrant in Portugal, 63, profile 3).

Those of working age had less faith in the future of public pension systems and specifically the portability of pensions in the context of Brexit. Muriel expresses the pessimism shared by several other interviewees, “I made contributions in Portugal for 5 years. I’ll probably not get to make use of it in the future. Especially not with Brexit. I suspect that it’s gone” (British migrant in Portugal, 60, profile 3).

Misinformation on the part of public institutions was also an obstacle to porting benefits. A few Portuguese interviewees living in the UK had received inaccurate information from bureaucrats, which had an enormous impact on migration trajectories. One example is Maria who lives in the UK with her husband:

“It’s hard for us. For sure, well we are not sure, but if we change our pension to Portugal, we were told, that we might have to pay more taxes, that taxes will increase, right? And because our retirement pension is bigger than the one [in Portugal], they might cut it (…) I don’t know. We are afraid that it might happen, so we will stay in between places, but we won’t be able to do that all the time, of course, we ’re getting older.” (Portuguese migrant in the UK, 77, profile 3).

The portability of other social benefits was not straightforward in practice for several of the Portuguese migrants living in the UK, due to regulatory and institutional complexity as well as discretion on the part of bureaucrats, as noted in other contexts (Perna, 2017; Lafleur & Mescoli, 2018). When Cátia became unemployed in Portugal, she moved to the UK to look for employment with the knowledge that she could port her Portuguese unemployment subsidy. However, UK institutions had difficulty in processing her application, as she explains in her own words:

“I filled in paper work without end (…) supposedly the Job Centre in the UK should have reported to Social Security in Portugal that I was there (…) but I never received anything (…) There was a failure in communication (…) I paid all of the contributions... but had no money to eat (…) But honestly I was so sick and tired of those guys [bureaucrats], I even had to come back to Portugal [to try to sort it out]. They won by exhausting me.” (Portuguese migrant in the UK, 34, profile 1).

The paperwork and the need to travel back to the origin country to try to provide the necessary information actually resulted in this particular migrant losing her social benefits, confirming findings of other studies (Scheibelhofer & Holzinger, 2018). This was less of an issue for British interviewees as, in general, they tried to avoid benefit take-up due to feeling a lack of deservingness.

Rather than relying on national social security systems, several British migrants still of working age pieced together an assemblage of social protection, including contributions in Portugal and the UK as well as property investment. This practice predates the 2016 Brexit referendum and reflects what several of our interviews described as a lack of trust in the political and administrative system. As Peter, who also makes social security contributions in Portugal, illustrates:

“I make voluntary national insurance contributions in the UK but it’s just, you keep your pension going (…) I haven’t completely ruled out going back to the UK, so just in case. .. up until with the recent events of the UK leaving the EU and things like that, I understood that it was relatively simple to transfer but that’s probably something to change so (…) I kept the property in the UK (…) it’s the flat which is probably more important as a kind of investment in the future (…) so in terms of pensions it is really property that, fingers crossed, is going to pay the pension when we eventually get there.” (British migrant in Portugal, 39, profile 2).

This “just in case” practice highlights the importance of return considerations (Carling & Pettersen, 2014; Sampaio, 2017) and a clear lack of trust in the portability of benefits within the EU, exacerbated in the aftermath of Brexit. Such arrangements are common among those who are locally contracted. However, those who engage in transnational professional activities with higher levels of mobility – some have UK registered businesses or work in multinational settings with remote working practices – make pension provisions in the UK and have little information on the functioning of the social security system in Portugal. A few Portuguese migrants interviewed in the UK also saw property investment as an additional safety net for retirement. As Amélia describes in her own words

“I just don’t count on the pension pot as my only safety net, so we’re thinking about other forms of investment, personal investment or through real estate, whatever, something that works as a pension supplement. For example, I don’t have one, but my husband has a Plano Poupança Reforma [Private Pension Scheme], and we intend to invest some money we have on the side in investment funds or something like that. ” (Portuguese migrant in the UK, 40, profile 2).

As such, low levels of trust in pension systems, whether public or private, was common among the British and Portuguese migrants we interviewed. Having parallel investments or maintaining a property in their country of origin provided a guarantee of a more financially secure retirement.

V. TACTICS IN EDUCATION AND HEALTH: WELFARE LEARNING AND INTERPERSONAL NETWORKS

Education and healthcare are available de jure to all the migrants we interviewed. In this section, we explore how this is enacted or experienced in practice and find quite significant differences between both groups. British migrants more frequently experienced obstacles related with a lack of knowledge of the system and language barriers. On the other hand, difficulties faced by Portuguese migrants in the UK relate to asymmetries in medical practices between the two countries, a lack of preventative medicine and cultural differences. Still, one similarity between both groups is the lack of planning or consideration of healthcare and education before migration. An element of happenstance or coincidence characterises the experiences of the respondents as they developed tactics when a particular need arose.

In the case of British respondents living in Portugal, accessing services greatly depended on migrants’ knowledge and “welfare learning” (Scheibelhofer & Holzinger, 2018). Several interviewees experienced difficulties due to lack of information. Some managed to overcome such obstacles by learning the system through adopting the tactics of locals. Local social capital and interpersonal networks were extremely important in accumulating knowledge and a richer understanding of the de facto functioning of the welfare system and some, mirroring the practices of the local population, created a mixed package of private and public health care. Peter, who is married to a Portuguese woman, illustrates the importance of having an ‘inside contact’ to access health services:

“We were very lucky with our health centre, the public one it’s fantastic (…) it’s easy for my wife to get appointments so we use it a lot (…) I’ve heard other stories that it’s difficult to get appointments (…) I think just the fact that the doctor, family doctor, has a long history with my wife’s family (…) he knows all the family (…) like for example, when I had a sore foot my wife phoned the health centre and they would say, “look, if your husband comes at 8 o’clock in the morning when the clinic starts then the doctor can see him quickly in 5 minutes”, so I guess that personal contact (…) I’ve heard stories of friends of friends who have contacts and go in the back door of hospitals (…).” (British migrant in Portugal, 39, profile 2).

Informal practices and knowledge of the everyday working of formal services helped when navigating the Portuguese system highlighting, first, the importance of information exchange as a form of informal social protection and, second, the ways that informal protection intertwine with formal social protection as argued by Bilecen and Barglowski (2015). Differential access to local social capital or weaker interpersonal social networks can thus create inequalities in terms of knowledge of the local system necessary for accessing specific public services (Faist, 2017). As such, the majority of the British migrants we interviewed resort to the private sector due to the low cost of insurance and services, difficulties with language and a lack of information on accessing public healthcare. Similar obstacles to accessing education were experienced meaning most families we interviewed opted for private education. As Laura, a 43 year-old-mother of three, explains:

“Yes, that would have been our first choice [Portuguese public education] (…) but also it was quite difficult to organize. When I tried to find the information about Portuguese schools, I found it virtually impossible. There didn’t seem to be any equivalent of Ofstedii reports (…).” (British migrant in Portugal, 43, profile, 2).

As stated previously, Portuguese respondents were much less likely to experience problems of access or lack of information. Rather several respondents described their dissatisfaction with the functioning of medical services in the UK and elaborated tactics to access services that were acceptable to them in line with perceptions of what constitutes good care. Dissatisfactions included the lack of preventative care in the UK, the hesitation on the part of British doctors to prescribe certain medical tests and cultural differences, such as not being able to call a doctor’s cell phone. One example of the tactics employed to get around the refusal of doctors in the UK to conduct exams, in this case routine blood tests, was to exaggerate symptoms, as Carla explains in her own words:

“It's a bit cultural. Once I went to the family doctor (…) I asked to do an analysis and she said "Just so you know, in this country we do not do blood tests for someone who is young and apparently healthy." but you also learn to deal with the health system (…) basically they prescribe for symptoms, it's not lying but dozens of times overdoing it a lot. (…) I think the medical class is much harder.” (Portuguese migrant in the UK, 30, profile 1).

Furthermore, cultural and emotional reasons also motivated many young migrants to turn to Portuguese clinics in the UK, despite having free care available within the NHS. Madalena, one such migrant, explains how she resorted to the private sector after negative experiences with the NHS:

“What I do is this, I go to this Portuguese clinic (…) You pay fifty euros, well, it depends on the exams and all that, but you have the same doctors and you can do something like “doctor, can I talk to you on the phone? It won’t take long”. (…) I learned that this Portuguese clinic exists through another Portuguese migrant. When I talk about it everybody knows it.” (Portuguese migrant in the UK, 30, profile 1).

Going against the general assumption that migrants constitute a burden for public services inherent in practices of welfare chauvinism (Kymlicka, 2015), our respondents shared testimonies that show different strategies developed specifically within the health field. Their tactics demonstrate the non-economic factors at stake when choosing medical care, an aspect often not reflected in the literature. There are of course exceptions, as older migrants who had lived in the UK for a much longer time were more dependent on the British National Health Service. Indeed, for this reason, one elderly couple who had planned to return to Portugal after retirement found themselves torn between staying and leaving:

“The health system, it’s better than in Portugal. He has diabetes and he has to take many pills and he doesn’t pay for anything (…) and at sixty five, we don’t pay anything for glasses, for the dentist, medication, transportation (…) even if you have a low pension you have a certain amount to live in the country, they [State] help you with the house taxes, and that’s why it’s hard for us to leave, because it’s better than the Portuguese system. And we always worked, so everything is according to the rules, and that is that. (…) Moreover, we have our family doctor just across our street.” (Portuguese migrant in the UK, 77, profile 3).

As we can see, far from “matter-of-fact conceptions of time” and a “linear or static framework that regulates life” (Collins & Shubin, 2015, p. 96) – in this case from working age to retirement – this couple are in an in-between state. Maria and her husband find themselves hesitant about their future, not being able to realise what would be a linear and desired trajectory – spending their retirement years back home – congruent with what Brettell (1979) coined as a “Portuguese ideology of return”. On one hand, their family is in Portugal – so the emotional side of things is back home –, on the other hand, particular (and practical) aspects mainly (if not exclusively) related to the health system impede their planned return. Though addressing the same health system, the two Portuguese respondents cited above present opposite views underlining the complexity in transnational and national positioning (Barglowski, Krzyzowski, & Swiatek, 2015). Another important tactic employed to overcome lack of information, trust in the quality of services and familiarity is the development of transnational welfare strategies, which we explore in the following section.

VI. TRANSNATIONAL SOCIAL PROTECTION: FLUIDITY AND IN-BETWEENESS

The emotional and economic attachments maintained between origin and destination countries – such as the maintenance or acquisition of property – as well as the prospect of ‘returning home’, creates the context in which transnational welfare practices developed. Despite the divergent experiences and tactics developed in each destination welfare context by both groups under study, a considerable proportion of the interviewees complete their healthcare ‘package’ with services ‘back home’. In the words of Levitt et al. (2017, p. 3) they “piece together a package of protections from more than one nation-state”.

Contrary to elderly Portuguese migrants who hold a crystallised and out-of-date notion of the Portuguese health system back in the 1960s and 70s, when they left Portugal, younger and often more highly qualified migrants, who constitute the recent wave of migration to the UK, frequently turn to the Portuguese public and private health system due to a lack of trust or dissatisfaction with the UK’s health sector. Differences in medical practices, noted in the last section, were often a motive for returning home for a doctor’s appointment or medical exams. One such example is the difference in vaccination plans and the frequency of ultrasounds during pregnancy in the two countries. Rute, a 30-year-old Portuguese migrant in the UK, returned home to Portugal to have ultrasounds in a private obstetric practice during her pregnancy.

“During my pregnancy I went to my gynaecologist, my obstetrician, my gynaecologist is also an obstetrician, so, when I went to Portugal I had an appointment with her and did an ultrasound in Portugal (…) I’ ve turned to the private sector in Portugal, for example, now with my son, the hepatitis B vaccine is out of the UK’s vaccination plan (…) so he had it in Portugal.” (Portuguese migrant in the UK, 30, profile 1).

Beyond actual medical considerations, familiarity and trust in the system and medical professionals compelled many individuals to return home for specific treatments:

“I’ve been going to the same dentist for 25 years. I was even in Porto this year and the day before I left to go I had a crown that fell out. I went back over to the UK to sort it out. It was really annoying though as I had to go back 3 times! (…) I think it’s just the familiarity. I mean, I wouldn’t know where to go here. So (…) I’m sure I could find out but (…) it’s too much bureaucracy. I don’t think economically it’s any more expensive here.” (British migrant in Portugal, 47, profile 1).

Even when in possession of high levels of social capital and reciprocal support systems, there were other emotional reasons that compelled some individuals to return home. Jo, a British migrant married to a Portuguese man, was planning a pregnancy and discussed at great length the kind of expectations she had for the birth and the experience she wanted to create using alternative birthing methods. The ability to communicate with carers and the cultural setting were pivotal:

“I don’t know if I want to be pregnant and actually give birth here. Like I, kind of, want to fly home because the thought of being in a hospital where people don’t speak my language, having the whole experience where you can’t communicate, that doesn’t seem good.” (British migrant in Portugal, 32, profile 1).

Another fundamental factor is tied to the traditional notion of the familialistic welfare state in Portugal, where the family has a central role in providing care. Notwithstanding the distance, a few of the Portuguese respondents use transnational care arrangements to fill the gaps in formal care. Madalena shares her experience:

“My Mother doesn’t work, she comes here [UK] very often, she might come to look after my son (…) I can picture in a few years that he will spend his vacations during the summer in Portugal or that my Mother will come here to look after him.” (Portuguese migrant in the UK, 30, profile 2).

As evident in other studies, the gendered dimension of transnational care is also revealed here, as grandmothers are positioned as caregivers compensating for the lack of informal care in the immigration country and simultaneously maintaining attachments with the country of origin (Barglowski, Krzyzowski, & Swiatek, 2015). In contrast, to the notion of nationally bounded welfare services existent in the host-country, these testimonies demonstrate the vital importance of transnational practices as well the weight of emotional and cultural factors. In addition, the role of perceptions is paramount here, shaping the way migrants look at how specific services are delivered.

VII. CONCLUSION

This paper adds to the growing literature on social protection among intra-EU migrants. In practice social protection rights are often difficult to exercise due to various obstacles. A lack of trust in the system casts doubts over ease of transferring benefits, particularly pensions, in the future. Moreover, difficulties in understanding different regulations and how administrative systems work in practice can limit the experiences of migrants. Information regarding social protection is almost invariably based on knowledge provided by informal sources, such as family and friends – showing the interplay between formal and informal elements. These sources at times facilitate access but can also result in misleading information and perceptions which straddles all domains of social protection. Faced with lack of information, together with the aforementioned lack of purview, migrants often develop creative solutions. Building on the work of Scheibelhofer and Holzinger (2018), we demonstrate the importance of “welfare learning”, gained through local social capital, capital, - as seen among the British migrants - thus inherently unequal, in navigating the system. We extend the concept of welfare learning to include the notion of good care, as migrants learn to adopt certain behaviours or tactics to influence the type of care they receive. This is illustrated through the ways that younger Portuguese migrants negotiate with institutional practices in place in the UK to receive preventative care, as they would in Portugal. Further, tactics include creating a mixed package of private and public care. As such, to understand how access works on the ground it is fundamental to study how migrants “learn the system”, and develop tactics built on the margins of formal social protection as well as how they piece two systems together in a complementary way

Indeed, transnational practices are a key tactic, whether to complement formal social protection through informal strategies – such as care – or, to overcome the real or perceived pitfalls of formal services and lack of trust, by balancing the two social protection systems. This is demonstrated though returning to the origin country for particular types of health care, through the “just in case” tactic of making double contributions to pensions in the origin and destination or by the provision of transnational childcare. This reiterates the necessity of a transnational approach in analysing the packages or assemblages of welfare constructed by migrants (Faist et al., 2015; Phillimore et al., 2016; Faist, 2017; Levitt et al. 2017). Non-economic factors and cultural values also bear a deep impact on how migrants ‘do’ social protection by turning to different services in particular places, showing the significance of emotional aspects in the development of their strategies. This was illustrated through the choice of the private Portuguese doctor in London for culturally sensitive care over free national health care, thus, underscoring the need to move beyond ideas exclusively based on the generosity of the welfare state. In the same vein, it is noteworthy how a perceived lack of deservingness or avoidance of negative stereotypes often lead migrants to distance themselves from any type of social benefit, in line with Ehata and Seeleib-Kaiser’s (2017) findings. In addition, rather than being planned from the outset, welfare tactics more often than not develop as needs arise, with an element of happenstance, due to life events or in times of personal or family crisis (in periods of unemployment or illness).

REFERENCES

Almeida, J. C., & Corkill, D. (2010). Portuguese Migrant Workers in the UK: A Case Study of Thetford, Norfolk. Portuguese Studies, 26(1), 27-40. [ Links ]

Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2002). Three World of Welfare Capitalism or More? A State-of-the-Art-Report. Journal of European Social Policy, 12(2), 137–58. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0952872002012002114

Bambra, C. (2007). Defamilisation and Welfare State Regimes. International Journal of Social Welfare, 16(4), 326–38. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2007.00486.x

Bambra, C. (2005). Worlds of welfare and the health care discrepancy. Social Policy and Society, 4, 31–41. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746404002143

Bartolini, L., Gropas, R., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2017). Drivers of Highly Skilled Mobility from Southern Europe: Escaping the Crisis and Emancipating Oneself. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43 (4), 652-73. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1249048 [ Links ]

Bilecen, B., & Barglowski, K. (2015). On the Assemblages of Informal and Formal Transnational Social Protection. Population, Space and Place, 21(3), 203-214. [ Links ]

Bilecen, B., & Sienkiewicz, J. (2015). Informal Social Protection Networks of Migrants: Typical Patterns in Different Transnational Social Spaces: Informal Social Protection Networks of Migrants. Population, Space and Place, 21(3), 227-243. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1906 [ Links ]

Boccagni, P. (2011). ‘Migrants’ Social Protection as a Transnational Process: Public Policies and Emigrant Initiative in the Case of Ecuador. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20(3), 318–25. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00747.x

Borjas, G. (1999). Immigration and Welfare Magnets. Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research), 17(4), 32. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/209933 [ Links ]

Brettell, C. (1979). ‘Emigrar para voltar’: a Portuguese ideology of return migration. Papers in anthropology, 20(1), 1-20.

Bruzelius, C., Chase, E., & Seeleib-Kaiser, M. (2016). Social Rights of EU Migrant Citizens: Britain and Germany Compared. Social Policy and Society, 15(3), 403-16. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746415000585 [ Links ]

Carling, J., & Pettersen, S. V. (2014). Return Migration Intentions in the Integration-Transnationalism Matrix. International Migration, 52(6), 13-30. [ Links ]

Carmel, E., Sojka, B., & Papiez, K. (2016). Free to move, right to work, entitled to claim? Governing social security portability for mobile Europeans. [ Links ] Welfare State Futures - WSF Working Paper Series; No. 1. Berlin, Germany: NORFACE Welfare State Futures.

Cavaco, C. (2005). Diferenciação regional da função turística [Regional differentiation of the touristic function]. In C. Medeiros (Dir.) Geografia de Portugal [Portugal’s Geography] (pp. 385-399). Lisboa: Circulo de Leitores.

Ciobanu, O., & Bolzman, C. (2015). The Interplay Between International Migration and the Welfare State in the Context of the Ageing of the Migrant Population. Scientific Annals of the “Al. I. Cuza” University, Iasi. Sociology & Social Work/Analele Stiintifice Ale Universitatii “Al. I. Cuza” Iasi Sociologie Si Asistenta Sociala, 8(2), 9-31.

Collins, F. L., & Shubin, S. (2015). Migrant Times beyond the Life Course: The Temporalities of Foreign English Teachers in South Korea. Geoforum, 62, 96-104. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.04.002 [ Links ]

De Certeau, M. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Ehata, R., & Seeleib-Kaiser, M. (2017). Benefit Tourism and EU Migrant Citizens: Real-World Experiences. In J. Hudson, C. Needham & E. Heins (Eds.), Social Policy Review 29: Analysis and Debate in Social Policy, (pp. 181-98). Bristol: Policy Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Oxford: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Faist, T. (2017). Transnational Social Protection in Europe: A Social Inequality Perspective. Oxford Development Studies, 45(1), 20-32. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1193128 [ Links ]

Faist, T., Bilecen, B., Barglowski, K., & Sienkiewicz, J. J. (2015). Transnational Social Protection: Migrants’ Strategies and Patterns of Inequalities. Population, Space and Place, 21(3), 193-202. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1903

Giulietti, C. (2014). The Welfare Magnet Hypothesis and the Welfare Take-up of Migrants. IZA World of Labor, 37. Doi: https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.37 [ Links ]

Glick Schiller, N., & Levitt, P. (2006). Haven’t We Heard This Somewhere Before? A Substantive View of Transnational Migration Studies by Way of a Reply to Waldinger and Fitzgerald. Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Center for Migration and Development, Working Papers, 6(1).

Góis, P., Marques, J., Candeias, P., Ferreira, B., & Ferro, A. (2016). Novos destinos migratórios: a emigração portuguesa para o Reino Unido [New migration destinations: Portuguese emigration to the United Kingdom]. In J. Peixoto, I. Oliveira, J. Azevedo, J. Marques, P. Góis, J. Malheiros & P. Madeira (Orgs.), Regresso Ao Futuro: A Nova Emigração E a Sociedade Portuguesa [Back to the Future: New Emigration and the Portuguese Society] (pp. 71-108). Lisboa: Gradiva. [ Links ]

Hockey, J., & James, A. (2003). Social Identities Across the Life Course. Contemporary Sociology-a Journal of Reviews - CONTEMP SOCIOL. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/009430610403300317 [ Links ]

Justino, D. (2016). Emigration from Portugal: Old Wine in New Bottles? | Migrationpolicy.org. Washington: Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/emigration-portugal-old-wine-new-bottles

King, R., Warnes, T., & Williams, A. (2000). Sunset Lives: British Retirement Migration to the Mediterranean. Berg: Publishers. [ Links ]

Kvist, J. (2004). Does EU Enlargement Start a Race to the Bottom? Strategic Interaction among EU Member States in Social Policy. Journal of European Social Policy, 14(3), 301-18. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928704044625

Lafleur, J. M., & Mescoli, E. (2018). Creating Undocumented EU Migrants through Welfare: A Conceptualization of Undeserving and Precarious Citizenship. Sociology, 52(3), 480-496. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518764615 [ Links ]

Levitt, P., Viterna, J. Mueller, A., & Lloyd, C. (2017). Transnational Social Protection: Setting the Agenda AU - Levitt, Peggy. Oxford Development Studies, 45(1), 2-19. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1239702 [ Links ]

Montezuma, J., & McGarrigle, J. (2018). What motivates international homebuyers? Investor to lifestyle ‘migrants’ in a tourist city. Tourism Geographies. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1470196

Moreno, L. (2007). Desenvolvimento Territorial – de um sentido ocidental às orientações coesivas para um meio rural inovador: Caminhos e caminhantes [Territorial Development – from a western sense to the cohesive guidelines for an innovative rural environment: Paths and walkers]. Lisboa: Universidade de Lisboa.

Peixoto, J., Marçalo, C., & Tolentino, N. (2011). Imigrantes E Segurança Social em Portugal [Immigrants and the Social Security in Portugal]. ACIDI. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cbdv.200490137/abstract [ Links ]

Perna, R. (2017). Re-bounding EU citizenship from below: Practices of healthcare for ‘(il)legitimate EU migrants’ in Italy. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(5), 829-848. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1362977

Phillimore, J., Humphris, R. Klaas, F., & Knecht, M. (2016). Bricolage: Potential as a Conceptual Tool for Understanding Access to Welfare in Superdiverse Neighbourhoods. IRiS Working Paper Series, 14. Doi: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4581.5284 [ Links ]

Pires, R. P., Pereira, C. Azevedo, J., Vidigal, I., & Moura Veiga, C. (2018). Emigração Portuguesa. Relatório Estatístico 2018 [Portuguese Emigration. Statistical Report 2018]. Lisboa: Observatório da Emigração e Rede Migra, CIES-IUL, ISCTE-IUL. Doi: https://doi.org/10.15847/CIESOEMRE052018 [ Links ]

Razin, A., & Sadka, E. (2000). Interactions between International Migration and the Welfare State. [ Links ] CESifo Group Munich, CESifo Working Paper Series.

Rocha, R. X. (2018). O brexit e os imigrantes portugueses no Reino Unido [Brexit and the Portuguese immigrants in the United Kingdom]. (Dissertação de mestrado). Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa.

Sampaio, D. (2017). Ageing ‘here’or ‘there’? Spatio-temporalities in older labour migrants’ return aspirations from the Azores. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, 52(106), 49-64. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18055/Finis9961

Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras. (SEF). (2019). Relatório de Imigração, Fronteiras e Asilo 2018 [Immigration, Borders and Asylum Report 2018]. Oeiras: SEF. Retrieved from https://sefstat.sef.pt/Docs/Rifa2018.pdf [ Links ]

Scheibelhofer, E., & Holzinger, C. (2018). ‘Damn It, I Am a Miserable Eastern European in the Eyes of the Administrator’: EU Migrants’ Experiences with (Transnational) Social Security. Social Inclusion, 6(3), 201-209. Doi: https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v6i3.1477

Sinn, H. W. (2004, July 13). Europe faces a rise in welfare migration. Financial Times. [ Links ]

Tiwari, I. (2011). State Welfarism and Social Welfare Policy (Protection Policy) in Asia: A Quadripartite Indistinct/Sluggish Nexus of International Propagandas, Slothful State, Moribund Family, and Right-Prone Individual? Conference: International Conference on Social Protection for Social UK: Institute of Development Studies. [ Links ]

Torkington, K. (2012). Place and Lifestyle Migration: The Discursive Construction of ‘Glocal’ Place-Identity. Mobilities, 7(1), 71-92. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2012.631812

Trenz, H. J., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2017). Complex and Dynamic Integration Processes in Europe: Intra EU Mobility and International Migration in Times of Recession. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(4), 546–59. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1251013

Recebido: maio 2019. Aceite: outubro 2019.

NOTAS

i http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/portugal-successful-reforms-have-underpinned-economic-recovery.htm

ii UK Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills.