Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.113 Lisboa abr. 2020

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis17553

ARTIGO

Aesthetics of super-diversity: the cantonese ancestral clan building as a social integration platform

Estética da super-diversidade: o edifício do clã ancestral cantonês enquanto plataforma de integração social

Esthetique de la super-diversite: le batiment du clan ancestral cantonais en tant que plateforme d’integration sociale

Estética de la superdiversidad: la construcción del clan ancestral cantonés como una plataforma de integración social

Rachel Chan Suet Kay1

1Research Fellow, National Institute of Ethnic Studies (n-KITA), National University of Malaysia (UKM), 43600 UKM, Bangi, Selangor, Malásia. E-mail: rachelchansuetkay@ukm.edu.my

ABSTRACT

In the quest to develop cities for the long run, the debate is whether to retain elements of culture or to reinvent such spaces for new uses. Cultural heritage preservation thus becomes an issue in urban planning. Heritage sites and buildings are currently facing a great threat from new urban development particularly in developing countries including Malaysia. Nonetheless, there are those who argue for the preservation of local identity in the face of urban development. They claim that within the Kuala Lumpur City Centre, there are areas rich in diversity of identity, and these should be made more visible. This paper uses the case study of Chan See Shu Yuen, a historically significant Cantonese ancestral clan association building which houses both tangible and intangible cultural heritage in the heart of Kuala Lumpur. Through a mixed-method approach, combining interviews, surveys, content analysis, photography, and videography, I outline how this clan association increases social cohesion through its continued functions of providing aesthetic value and being a tourist attraction. This makes the case for the continued retention of historical buildings and practices, despite overarching social changes such as super-diversity.

Keywords: Cities and culture; cultural heritage; super-diversity.

RESUMO

Na busca pelo desenvolvimento de cidades a longo prazo, importa debater se devemos reter elementos da cultura ou reinventar esses espaços para novos usos. A preservação do património cultural torna-se, assim, um problema no planeamento urbano. Os sítios e edifícios do património estão atualmente a enfrentar a grande ameaça do novo desenvolvimento urbano, particularmente nos países em desenvolvimento, incluindo a Malásia. No entanto, existem aqueles que defendem a preservação da identidade local em face do desenvolvimento urbano; afirmam que no centro da cidade de Kuala Lumpur, há áreas ricas em diversidade de identidade, e estas devem ser tornadas mais visíveis. Este artigo usa caso de estudo, Chan See Shu Yuen, um edifício de associação de clãs ancestrais Cantonense historicamente significativo que abriga patrimónios culturais tangíveis e intangíveis no coração de Kuala Lumpur. Através de uma abordagem mista, combinando entrevistas, pesquisas, análise de conteúdo, fotografia e videografia, descrevo como a associação deste clã aumenta a coesão social através das suas funções continuadas de prover valor estético e ser uma atração turística. Isso justifica a retenção contínua de edifícios e práticas históricas, apesar das mudanças sociais abrangentes, como a super-diversidade.

Palavras-chave: Cidades e cultura; património cultural; super diversidade.

RÉSUMÉ

Dans le but de développer les villes sur le long terme, le débat est de savoir s’il faut conserver des éléments de la culture ou réinventer de tels espaces pour de nouveaux usages. La préservation du patrimoine culturel devient donc un problème dans la planification urbaine. Les sites et bâtiments patrimoniaux sont actuellement menacés par le nouveau développement urbain, en particulier dans les pays en développement, y compris la Malaisie. Néanmoins, il y a ceux qui plaident pour la préservation de l’identité locale face au développement urbain. Ils affirment qu’il existe dans le centre-ville de Kuala Lumpur des zones riches en diversité d’identité et qu’il conviendrait de les rendre plus visibles. Cet article utilise l’étude de cas de Chan See Shu Yuen, une association de clans ancestraux cantonais d’importance historique et qui abrite un patrimoine culturel matériel et immatériel au cSur de Kuala Lumpur. En utilisant une méthode mixte associant des entretiens, enquêtes, analyse de contenu, photographies et vidéographie, on décrit comment l’association de ce clan accroît la cohésion sociale grâce à ses fonctions continues de valeur esthétique et d’attraction touristique. Cela plaide en faveur de la préservation continue des bâtiments et des pratiques historiques, malgré les changements sociaux globaux tels que la super diversité.

Mots clés: Villes et culture; patrimoine culturel; super-diversité.

RESUMEN

En la búsqueda del desarrollo a largo plazo de las ciudades, el debate es si debemos retener elementos de la cultura o reinventar estos espacios para nuevos usos. La preservación del patrimonio cultural se convierte entonces en un problema en la planificación urbana. Los sitios y edificios patrimoniales se enfrentan actualmente a una gran amenaza debido al nuevo desarrollo urbano, particularmente en los países en desarrollo, incluido Malasia. Sin embargo, hay quienes defienden la preservación de la identidad local frente al desarrollo urbano. Afirman que, dentro del centro de la ciudad de Kuala Lumpur, hay áreas ricas en diversidad de identidad, y estas deben hacerse más visibles. Este artículo utiliza el estudio de caso de Chan See Shu Yuen, un edificio de asociación de clanes ancestrales cantonés, históricamente significativo que alberga un patrimonio cultural tangible e intangible en el corazón de Kuala Lumpur. A través de un enfoque mixto, que combina entrevistas, investigaciones, análisis de contenido, fotografía y videografía, describo cómo la asociación de este clan aumenta la cohesión social a través de sus funciones continuas de proporcionar valor estético y de ser una atracción turística. Esto justifica la retención continua de edificios y prácticas históricas, a pesar de los amplios cambios sociales, como la súper diversidad.

Palabras clave: Ciudades y cultura; patrimonio cultural; super diversidad.

I. Urbanization, modernization, and heritage preservation

In the quest to develop cities for the long run, the debate is whether to retain elements of culture or to reinvent such spaces for new uses. Cultural heritage preservation thus becomes an issue in urban planning. Studies of urbanisation have evolved greatly since its beginnings in sociological thinking, mainly led by the Chicago School, which in turn drew from Spencer’s (1864) interpretation of Darwinism. Various imaginations of the city exist, such as Burgess (1924, 1925, 1927) who viewed it as a concentric circle in which each circle generates its own homogeneous culture (Harding & Blokland, 2014); Marxism which emphasised the marginalised groups’ perspective and subjectivity (Harding & Blokland, 2014); and the tensions between adopting the viewpoint of the researcher versus adopting the viewpoint of the researched (Harding & Blokland, 2014). However, a key challenge that urbanisation scholars unanimously acknowledge is the challenge of modernity, as well as postmodernity (Harding & Blokland, 2014).

Defining modernisation is even harder than defining urbanisation (Germani, 1973). However, to provide a starting point, this paper begins with Rostow’s definition of modernisation. In his seminal work The Stages of Economic Growth, Rostow (1960) outlined five stages of modernisation, namely traditional society, the pre-conditions for take-off, take-off, the drive to maturity, and the era of high consumption (Robbins, 2001). Modernisation theories emphasised the transmission of modern attitudes and values which accompanied technological progress (Robbins, 2001); while postmodernity is characterised by the conceptual tearing down of metanarratives such as traditional beliefs (Giddens, 2013). The processes of modernisation uprooted many people from their localities, relocating them within urban areas (Walsh, 1992). Examined in the context of heritage preservation, modernity and postmodernity have distanced people from many of the processes which affect their lives, including a connection with the past (Walsh, 1992). In the 1980s and 1990s in particular, there was a boom in the museum and heritage industry, possibly due to the need to re-establish this connection to the past through institutionalised discourse (Walsh, 1992).

However, Walsh (1992) also problematises this situation, because there is an increasing distance between the producers and consumers of this intersubjective discourse about the past. For example, one challenge faced by heritage sites in developing nations is that of intensified urban problems due to rapid economic development and population growth (Said, Aksah, & Ismail, 2013). Historical buildings have also been sacrificed to make way for urban renewal projects (Al-Obaidi, Sim, Ismail, & Kam, 2017). This, in turn, might threaten social cohesion especially in a society with ethnic and cultural diversity.

This paper thus demonstrates the maintenance of ethnic social cohesion in Malaysia through cultural heritage preservation, using the case study of the Chinese clan association building, an ethnic Chinese social institution which is still widely found in existence today.

II. Dissonant ethnicity and heritage in multicultural societies

One of the pertinent reasons for preserving Chinese cultural heritage is to contribute to the objectives of the Malaysian National Culture Policy, which focuses on maintaining the multiracial diversity of Malaysia. The Chinese form the second largest ethnic group among Malaysians (Statistics Department of Malaysia, 2014) and are part of a huge global Diaspora, making their issues of identity complex and noteworthy of study. Purcell (1967) who wrote the landmark study of the Chinese in Malaya, outlined the composition of dialect groups migrating from Guangdong and Fujian in southern China to Malaya. Different economic activities were attributed to different dialect groups. The largest dialect groups, the Hokkiens and Teochews, were engaged in trading, real estate, large plantation-scale commercial agriculture, and retail shop keeping. The Cantonese, a smaller dialect group, were engaged in artisans, retail, and “together with Malays, clearing the dense tropical jungle and thick undergrowth and preparing the land for cultivation” (Purcell, 1967, p. 44, 60). The other smaller dialect groups included Hakkas and Hainanese who specialised in food preparation as cooks and proprietors in kopitiams (Purcell, 1967; in Ooi 2015). The largest Chinese dialect group in Malaysia is the Hokkien, followed by the Hakka and the Cantonese (Ember, Ember, & Skoggard, 2004). However, while numerous studies have been made on the Hokkien and Hakka, studies on the Cantonese almost do not exist.

This study stems from the project, “Super-diversity Networks: Cantonese Clan Associations in Malaysia as Transnational Social Support System”, which examined in particular the Chan See Shu Yuen Kuala Lumpur & Selangor Clan Association (CSSYKL). CSSYKL is an example of a historical heritage building which continues to function today albeit in an evolved form. The research objective is to examine how the Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Association Kuala Lumpur and Selangor, as a historical and tourist space, continues to act as a social integration platform for the citizens of Kuala Lumpur, in the era of super-diversity.

This research objective was fulfilled through fieldwork consisting of participant observation which included photography, videography, content analysis of secondary documents, and focus group discussions with the clan’s Board of Directors, staff, and members, and a survey of tourists. I initially conducted interviews with the clan association directors, staff, as well as elders and youth members in order to understand the history of the place and its recent development, while being present on a weekly basis to observe the clan association activities which included celebrating major festivals such as Chinese New Year, Mid-Autumn Festival, and Malaysia Day. I recorded these celebrations through photography and videography, noting instances of ethnic diversity in these celebrations. I then moved on to observing tourist behaviour in the CSSYKL heritage building, as well the surrounding ethnic enclave. With the permission of CSSYKL, I prepared a box containing my questionnaire and signage inviting tourists to fill in an opinion survey regarding their visit, placing this next to the tourist brochures.

Heritage sites and buildings are currently facing a great threat from new urban development particularly in developing countries, including Malaysia (Tamjes, Rani, Wahab, Che Amat, & Ismail, 2017). The scarcity of land supply in the heart of Kuala Lumpur, for instance, has exposed its heritage sites to a severe form of commercialization pressure because of the land price (Tamjes et al., 2017). Indeed, Malaysia had initiated the effort of conserving heritage buildings in the past half century (Azhari & Mohamed, 2012). Studies of cultural heritage and tourism in Malaysia took off circa 2008, after the listing of Malaysian cities George Town (Penang) and Malacca on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

However, it appears that public awareness and involvement is rather slow blooming (Azhari & Mohamed, 2012). This led the authors to advocate for more initiatives to educate the public on the importance of conserving historical buildings, namely because they function as tourism landmarks and attractions for Kuala Lumpur as well as beautifying the city (Azhari & Mohamed, 2012).

In addition, another competing issue is the standardisation of Kuala Lumpur’s urban aesthetic, where the traditional urban environment in developing countries has been constantly replaced by modern structures with standardised images (Ujang, 2014). This poses the threat of eclipsing people’s psychological place attachment to Kuala Lumpur. Norsidah Ujang (2014) found through interviews and observations that users imposed various meanings onto places such as traditional shopping streets. However, urban planners often focus on the physical qualities of development at the risk of ignoring place attachment, to the extent of creating cities with a global character but devoid of local expression of culture (Ujang, 2014). An example cited by Norsidah Ujang (2014) was the case of Chinatown in Kuala Lumpur (the area surrounding Petaling Street) whose character is gradually diminishing (Cardosa, 2002).

Nonetheless, there are those who argue for the preservation of local identity in the face of urban development. Some mention that Kuala Lumpur needs to create a distinctive city identity and image if it is to achieve its bigger goal of becoming a World-Class City by 2020 (Ibrahim, Wahab, Shukri, & Sharif, 2017). They claim that within the Kuala Lumpur City Centre, there are areas rich in diversity of identity, and these should be made more visible (Ibrahim et al., 2017). The process of regenerating existing urban marketplaces should consider the components that make them unique, to retain a sense of place (Ibrahim et al., 2017). Ethnic events can help to reinforce a sense of cultural identity and community cohesion (Smith, 2003). For example, festivals can be used to increase racial tolerance through cross-cultural exchange and education (Smith, 2003). The development of ethnic festivals can sometimes help to raise the profile of local community groups, leading to a greater understanding of and interest in their culture (Smith, 2003).

Malaysia is multicultural and is comprised of several main ethnic groups, often classified as the Malays, the Chinese and the Indians (Hirschman, 1987); as well as the indigenous groups whose majority is the Semai (Arabestani & Edo, 2011), and in East Malaysia the Kadazan-Dusun (Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center, 2015). Currently many other ethnic groups exist in the country as well, due to a high level of international migration fuelled by the search for job opportunities. Over two million migrant workers are found in Malaysia in industries such as plantation, construction and the domestic sector, coming largely from Indonesia, Bangladesh, and the Philippines (Lin, 2006). In total, Malaysia’s population for the year 2014 is 30 097 900 (Statistics Department of Malaysia, 2014).

Malaysia is a nation-state based on diversity - ethnic, religious, linguistic, and many others. In addition, as Malaysia is a formerly colonised country, it faces the challenges of “unity in diversity”. This relates to the issue of plurality, which can be viewed as positive, conflicting, and ideal (Shamsul & Yusoff, 2014). The positive trait arises from diversity that is packaged as a product; the negative trait stems from differences within social categorisations such as ethnicity, religion, language, culture, and worldview; while the ideal trait emerges from the human emotional need for unity (Shamsul & Yusoff, 2014).

The development of Kuala Lumpur occurred in several stages. In Malaysia, statistics show that Kuala Lumpur has grown increasingly urbanised over time (McGee, 2017). Most studies of Malaysia’s urbanisation peg its starting point at the turn of the 20th century. Since 1900, the level of urbanisation in Malaysia has climbed from 10% in 1911 to 28,4% in 1970, and 61,8% in 2000 (Yaakob, Masron, & Masami, 2010). The main reason for this was that for the past century, Malaysia has experienced rapid urban population growth, beginning with towns prospering from colonial tin mining (Masron, Yaakob, Ayob, & Mokhtar, 2012). During British colonisation in Malaya, basic infrastructure such as transportation and utilities were built to support commercial, financial, social and administrative functions to further exploit resources such as tin and rubber (Ho, 2008). Hence, post-Independence Malaysia experienced a small change in the rural-urban balance only from 1957 to 1970 (Hirschman, 1976). This was due to the growth of towns into the urban classification, rather than due to a redistribution of the population into previously founded urban settlements (Hirschman, 1976). Meanwhile, after 1970, the level of urbanisation in Peninsular Malaysia rose from 33% in 1957 to 73% in 2014, with a sharp reduction in agricultural employment, though agricultural productivity grew (McGee, 2017). While rural-urban inequity declined, regional differences remained, with an urbanisation rate of 38% in Old Peninsular Malaysia, and 70% in New Peninsular Malaysia, in 2000 (McGee, 2017).

Following this, rapid urbanisation during the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated a greater impact on urban and housing development in Kuala Lumpur (Shuid, 2004). However, this culminated in a “counter-urbanisation of development” during the 1990s, due to better economic conditions and changing urban dwellers’ lifestyles (Shuid, 2004). To better understand the process of urbanisation in Malaysia, a three-phase urbanisation taxonomy was proposed, beginning with the nascent stage; the pseudo stage, and finally the rise of the mega urban region (Hadi, Idrus, Shah, & Mohamed, 2010).

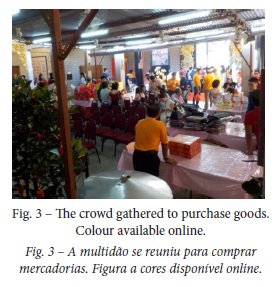

According to Dick & Rimmer (1998), due to colonialism the pattern of development in South East Asian cities had been gradually converging with Western urban trends. The elements of a city involve the home (the trip origin), the destinations of offices, shops, restaurants, schools, hospitals, sports centres, hotels and cinemas - which are linked by automobile technologies such as the motor car and public transport (Dick & Rimmer 1998). Dick & Rimmer (1998) comparatively outlined the historical stages of urban development in both Western and South East Asian cities as follows. At the moment, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia’s capital city is listed in the category of semi-bundled towns (table I).

III. Material culture, intangible culture, and social cohesion

A historical building is one which has surpassed a century (Feilden, 1994; in Hashim, Aksah, & Said, 2012). There are around 39 000 historical buildings all throughout Malaysia, built between the years 1800 and 1948, classified as pre-war buildings (Idid, 1995; in Hashim et al., 2012). Kuala Lumpur’s built heritage dates back to the 1800s, where it evolved from a small mining town at the meeting point of the Klang River and the Gombak River (Yusoff, Noor, & Ghazali, 2014). In particular, Kuala Lumpur is home to many historical public buildings, such as the Sultan Abdul Samad Building, the Kuala Lumpur Memorial Library, the National Museum of History, the Kuala Lumpur Railway Station, and the Kuala Lumpur Textile Museum (Hashim et al., 2012). These buildings have great tourism potential, but are susceptible to deterioration due to lack of maintenance and insufficient restoration methods (Hashim et al., 2012). Heritage buildings in Kuala Lumpur fall under the definition of tangible heritage as outlined by UNESCO (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 2004).

If properly managed, heritage has plenty of potential for sustainable development (Hribar, Bole, & Pipan, 2015). Heritage can be instrumental in enhancing social inclusion, developing intercultural dialogue, shaping the identity of a given territory, improving the quality of the environment, providing social cohesion, stimulating the development of tourism, creating jobs and enhancing the investment climate (Dümcke & Gnedovsky, 2013). The concept of “cultural value” is intended to emphasize the developmental potentials of various forms of culture of a particular area (Hribar & Lozej, 2013). Hribar and Lozej (2013, p. 375) defines “cultural value” as “various tangible and intangible elements and individual natural elements of cultural significance and local origin that are identified by the stakeholders and have economic, social, ecological, or cultural developmental potential”. The “social value” of heritage meanwhile, was assessed by measuring social cohesion, community empowerment, skill and development learning (Dümcke & Gnedovsky, 2013). To achieve all these, a public participatory approach to heritage management is needed, as the public can identify and recognize suitable cultural values to incorporate them into a whole and upgrade them into a market product or a service (Hribar et al., 2015).

The discourse on the definition of “social cohesion” is fragmented. Its intellectual origins can be traced back to the founding sociologist Emile Durkheim (Pahl, 1991), and is often operationalised “in terms of the broader questions of social integration, stability and disintegration” (Chan, To, & Chan, 2006, p. 275). Meanwhile, social psychologists such as Bollen and Hoyle (2001) had also made a major contribution to this discourse, suggesting that there are two perspectives to cohesion: objective and perceived (Chan et al., 2006). Subsequently, policy analysts in Canada developed the concept of “social cohesion” as a policy tool to promote multiculturalism, using a problem-solving approach to social cleavages (Chan et al., 2006). Finally, Chan et al. (2006, p. 290) offered an operationalisation of “social cohesion” where it is defined “as a state of affairs concerning both the vertical and the horizontal interactions among members of society as characterized by a set of attitudes and norms that includes trust, a sense of belonging and the willingness to participate and help, as well as their behavioural manifestations”. In Malaysia, “social cohesion” is described as a situation where there is peace, stability, prosperity, and wellbeing in a society, especially one that is multi-ethnic (Shamsul & Yusoff, 2014). “Social cohesion” is a prerequisite level before resolving “contradictions” that obstruct a community from achieving “unity” (Shamsul & Yusoff, 2014). These “contradictions” can be mapped out according to nine axes of social interactions, which are: ethnicity, religion, social class, education, language, generational gap, gender, political federalism, and urban-rural space divides Shamsul & Yusoff (2014).

Drawing from this potential, it is possible to make a list of various social occurrences which can increase social cohesion. Shamsul (2013) calls these “moments of unity” (Khalid, 2016). These could be any social phenomenon that encourages individuals to build rapport with each other. These phenomenon act as meeting points, or “integration platforms” in the economic, political, educational, and cultural dimensions. Because they are grassroots-based, they act from the “everyday-defined” “bottom-up”, rather than from the “authority-defined” “top-down”.

“Social cohesion” is much sought after because it has been regarded as a solution to problems of increasing fragmentation, conflict, and inequality between different social and ethnic groups (Turok & Bailey, 2004). According to UN-Habitat (2013), by 2050, the world’s urban population is expected to nearly double, making urbanization one of the twenty-first century’s most transformative trends. Populations, economic activities, social and cultural interactions, as well as environmental and humanitarian impacts are increasingly concentrated in cities, and this poses massive sustainability challenges in terms of housing, infrastructure, basic services, food security, health, education, decent jobs, safety and natural resources, among others (UN-Habitat, 2013). In addition, the phenomenon of “super-diversity” (Vertovec, 2007) contributes to this mix, as communities become more complex in their possession of identities. Super-diversity is the condition of migrants possessing more than just attributes of ethnicity or country of origin, but those that extend to net inflows, countries of origin, languages, religions, gender, age, space/place, transnationalism, and migration statuses (e.g. workers, students, spouses and family members, asylum-seekers and refugees, irregular, illegal or undocumented migrants, and new citizens) (Vertovec, 2007). In response to these changing patterns of migration, UNESCO (2016) stated that urban conservation and regeneration have contributed to strengthening cultural continuity, community participation, and social cohesion.

IV. Findings

CSSYKL is located on one end of Petaling Street, or Kuala Lumpur Chinatown, a major tourist attraction. It was originally a clan association set up by a Cantonese founder, the late Honourable Chan Sow Lin, who functioned as an equivalent to Chinese Kapitans such as Loke Yew. Chinese Kapitans, or Kapitan Cina, was a title given to Chinese entrepreneurs tasked with developing industrial activities in British colonial Malaya (Roda & Ahmad, 2010). At the time of Chan Sow Lin’s appointment as Selangor State Council member, the Kapitan Cina system had been abolished by the British colonial powers. Chan Sow Lin was an important figure in contributing to the creation of many social institutions which facilitated the migration of the southern Chinese to Malaya, spanning “from one’s birth to one’s death”. This was because he founded institutions which ranged from hospitals, schools, companies, as well as crematoriums and cemeteries. Sources cite that Chan played many roles including being “the inventor of the Nai Chiang tin mining system”, being “the managing director of an engineering firm which was on par with European firms”, being “peacemaker in the Larut Wars, receiving a medal from the Viceroy of Guangdong who was sent by the Emperor of China for his efforts in promoting Chinese education”, receiving another “medal from the Chinese Ambassador to England for philanthropic work”, and being an “appointed member of the Selangor State Council” (Overseas Chinese in the British Empire, 2011). Another three founders joined Chan Sow Lin in founding the CSSYKL, namely Chan Choon, Chin Sin Hee, and Chan Choy Thin (Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Association, 2016). The CSSYKL was established in 1896 as a Clan Consanguinity Organisation (Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Association, 2016).

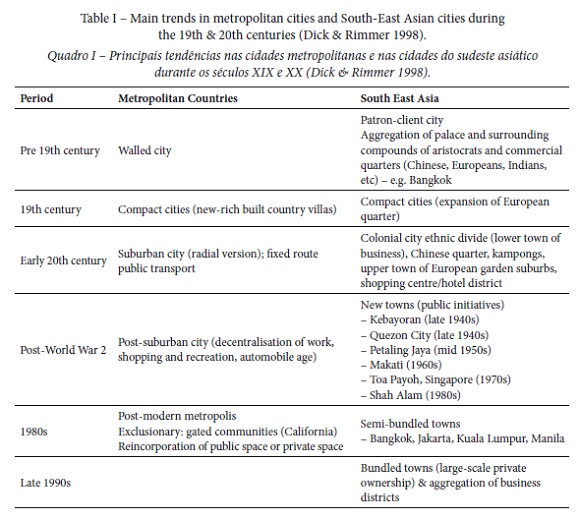

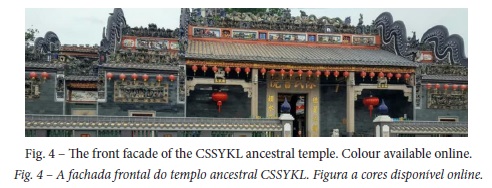

The CSSY has its headquarters in Guangzhou, Mainland China called the Chen Clan Ancestral Hall, upon which the Kuala Lumpur one is modelled, physically and organisationally. This hall originally functioned as an “academic temple” for candidates’ preparation for the Qing Dynasty imperial examinations and was the template for the Chan See Shu Yuen built by its descendants in Malaysia. It prides itself on the inherited “Ling Nan Style of Architecture” derived from Guangzhou, Guangdong. The “CSSYKL building was modelled after the Chan Clan Association in Xi Guan, Guangzhou China as a design blueprint, which combined the characteristics of a family temple and an ancestral hall features, incorporating the ancient Cantonese-style art and Southern China architecture, which has a mix of Han and Bai Yue elements.” (Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Association, 2016). The CSSYKL has persisted in functioning ever since. “For more than a century, the Chen’s descendants of CSSYKL had kept the tradition alive and upheld its core values generation after generation. Celebration and paying homage to the birth commemoration of Chen’s Great Grand Ancestors, Honourable Shun Di, Honourable Chen Shi, and Honourable Chen Yuan Guang, Spring and Autumn Festival Praying are the main occasion for CSSY. Other celebrations like CSSYKL anniversary, Lunar New Year, Duan Wu, Lanterns Festival, Winter Solstice Festival, etc. will not be missed yearly. These everlasting practices of CSSY is likened to the immortal of incenses.” (Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Association, 2016).

Clans are made up of kinship-bound families (Yen, 1981). The clan is a group formed with a patrilineal blood relationship based on a common ancestor at its core (Sun, 2005). Hence, the Chinese clan association is an organisation whose membership includes individuals with the same surname (Ch’ng, 1995 in Makmur, 2018). In the past, Chinese clan associations possessed several main functions. These were preserving the family unit, which is of paramount importance to Chinese identity (Sun, 2005); affiliation with one’s dialect group; maintaining Confucianism as their main value system, comprising concepts such as justice, work ethic, and respect for parents (Acs & Dana, 2001); operating as hybrid institutions combining British law and Chinese customs (Cheng, Li, & Ma, 2013); providing a vocational education system to transmit entrepreneurial knowledge and skills from successful to budding entrepreneurs (Loewen, 1971; Light, 1972; Wong, 1987; Dana, Etemad, & Wright, 2000); responding to the growth of the nation state and changing socio-political environment besides taking care of its members’ needs (Chan, 2003); and organising religious ceremonies such as celebrating Chinese festivals, providing community representation, and arranging funerals and burials (Ng, 2002; Tan, 2018).

In the past, Chinese clan associations used to provide lifelong social, cultural, and economic support to its members. Today, an additional function of this clan association is also to boost tourism. A great number of tourists come from various European countries as well as China and Malaysia itself (figs. 1 to 4). These are recorded in CSSYKL’s guest record book, and also observed during participant observation where tourists trickle in daily with their cameras. The CSSYKL has been listed as a historical relic in the protection of ancient buildings by the Malaysian government (Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Association, 2016). It was also featured as one out of twelve places to visit on a tourist trail, designated by the Ministry of Tourism and Culture of Malaysia (Malaysia Tourism Centre, 2017).

Chinese cultural identity and social networks are generated overseas rather than in mainland China itself (Long & Han, 2008). Some examples of these are clan associations based in Southeast Asia, where its members’ ancestors migrated from the Southern Chinese regions of Guangdong and Fujian originally (Long & Han, 2008). These networks exerted profound influence upon Chinese overseas, especially in business (Long & Han, 2008). Aside from this, they also provided lifelong social, cultural, and economic support through helping members find employment, providing basic necessities such as education and healthcare, helping destitute members, fostering traditional Chinese values, celebrating Chinese festivals, providing community representation, and even arranging funerals and burials (Ng, 2002). According to Ma (2012), Cantonese temples and their associated organisations have become symbols that facilitate communication among the Chinese, as well as promoting social networking among Chinese communities in Malaysia and beyond. Currently, there are over 4000 Chinese clan associations in Malaysia, and they are keen on investment opportunities with mainland China due to its Belt and Road initiative (Malaysian Chinese Association, 2017).

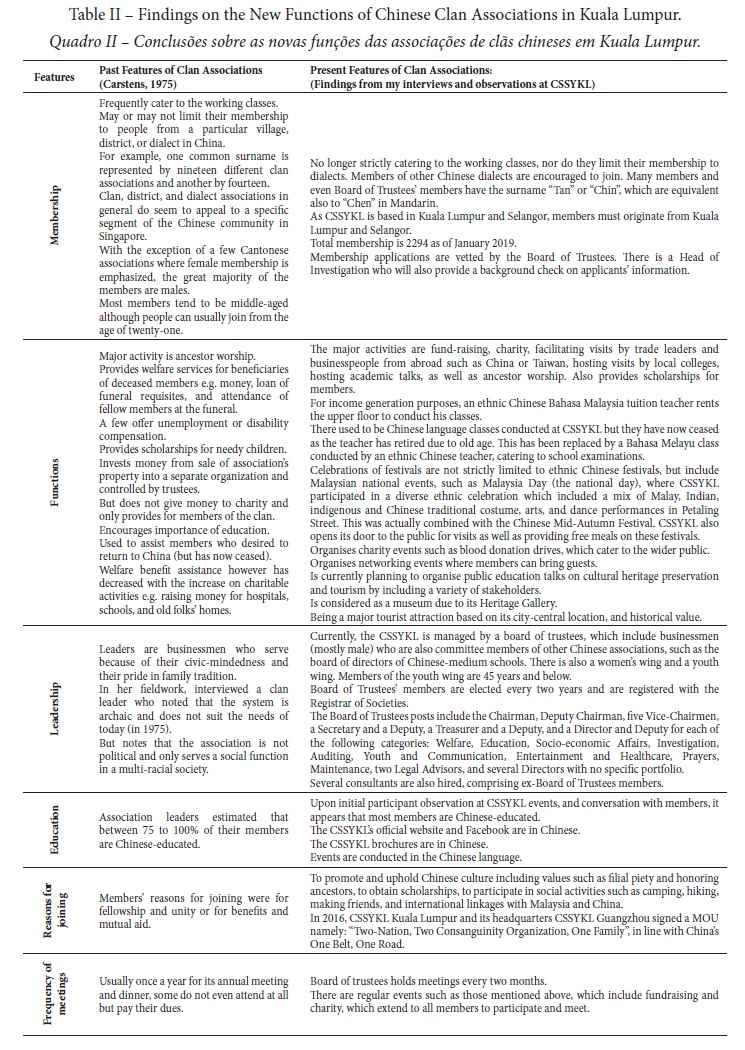

Meanwhile, in terms of preserving the intangible aspect of Cantonese cultural heritage, the old and new functions have been sustained. Table II compares the early functions of clan associations in Singapore, Malaysia’s southern neighbour, as observed by Carstens in 1975, to that which I found in my participant observation in the CSSYKL in the present day.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

V. Discussion and conclusion

As outlined by Dick and Rimmer (1998), Kuala Lumpur is at the stage of a semi-bundled city, which entails a mixture of private ownership and existing heritage buildings. However, the challenge for urban planners is to standardise, or harmonise the different aesthetics of heritage buildings (which come from a different period) with the more contemporary private owned buildings. For example, along the one end of Petaling Street, where CSSYKL is located, one can witness a mish-mash of historical and contemporary styles of architecture.

This conundrum can be viewed under the lens of urban design aesthetics. According to Nasar (1994), urban designers are responsible for shaping the physical and spatial character of urban development. To do this, they need to take into account formal and symbolic aesthetics, where the former refers to the structure of forms and the latter to human responses to the content of forms (Nasar, 1994). Yet, often there can be a mismatch between public and architects’ tastes (Nasar, 1994). However, the solution to achieving a successful urban aesthetic does not necessarily require uniformity, but instead, possess the attributes of pleasantness, excitement, and calmness (Nasar 1994). Nasar (1994) found that the attribute of pleasantness requires among others, “familiar and historical elements”. In the case of CSSYKL, it provides the historical elements as well as familiarity given its longstanding association with Kuala Lumpur’s history, and thus evokes the symbolic aesthetic. Formal aesthetics which surround CSSYKL however, include the sidewalks, signboards, public transportation, hotels, and business centres which serve to increase mobility within the city. However, these may clash with the symbolic appeal of places such as temples or ancestral halls, as the functions of worship contrast with the functions of mass transportation. This provides an interesting crossroad for the issue of tourism, given that the public transport and hotel facilities as well its central position as a business district both encourage tourists, and might deter them should they be historical enthusiasts.

This preservation of a “Chinatown” in Kuala Lumpur may be viewed in comparison to cases in other Chinese ethnic enclaves. In Malaysia, nation-building is met with the challenge of overcoming British epistemological colonisation, in which the postcolonial state has sought to realise its modernisation project (Shamsul Amri Baharuddin, 1996). The challenge would be the issue of modernising in a way that subscribes to the constructs of modernity, which is dominated by Western rationalisation, while maintaining ethnic authenticity and diversity. In post-independence Singapore, which has a different ethnic composition from Malaysia, where it is populated by a Chinese majority, its Chinatown was refashioned into a tourist attraction, though it still bears memory of a British colonial legacy (Kong, 2011; Yeoh & Kong, 2012). However, Kong (2011) notes that the attempt to use Chinese heritage as a uniting principle has not worked for the remaking of Singapore’s Chinatown, even among its own Chinese population.

In addition, it was also found that any inconsistency among historical building facades could have a negative impact on the city’s historical image (Askari & Dola, 2009). In their review of studies of Kuala Lumpur’s historical building conservation, Askari & Dola (2009) found that this was the case, as tourists were responsible for the evaluation of building facades, and they were likely to be affected by these visual elements when doing so. The most important visual elements were architectural style, followed by shape, decoration, and material; and the least important were colour and texture (Askari & Dola, 2009). Visual elements that were said to tarnish the historical images of Kuala Lumpur for visitors were inconsistent colours such as pink, yellow, and blue; while colours such as grey and white were found to be the most suitable in enhancing the historical image of the city’s streetscapes (Askari & Dola, 2009). In recent years, CSSYKL has undergone a complete repaint, from the colours green and red, to that of grey. This was done in tandem with the interest of maintaining the similarities between CSSYKL and the Chen Clan Ancestral Hall in Guangzhou. This also met the observation by the authors above who suggested they grey colour scheme as being more consistent with the historical image.

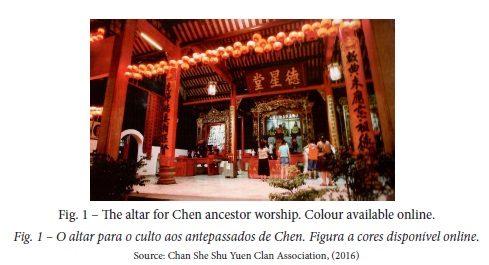

It is found that the CSSYKL acts as a tourist attraction in Kuala Lumpur, bringing in visitors from all continents across the globe. For example, in the sample page of the CSSYKL guest book above, there are tourists from Malaysia itself, Switzerland, Denmark, Ukraine, Austria, Mexico, Germany, Canada, New Zealand, and the Czech Republic. On other pages are also records of tourists from China and other continents such as Africa. This suggests that individuals from all these countries have visited Malaysia, and in particular CSSYKL, bringing home with them a piece of the experience. Tourists have been observed to trickle in daily, not in large groups but alone, in twos, or in small groups, sometimes with an accompanying tour guide. Some tour guides work closely with CSSYKL to bring in tourists. The tourists are usually armed with cameras or smartphones and were observed photographing the building’s interior and exterior. They will then be able to share this experience with others back in their home countries or elsewhere. Similarly, during participant observation, the author attended a fund-raising event, the Chinese New Year Food Festival 2019, in which members of CSSYKL organised an open bazaar selling a variety of local delights and merchandise to members of the public. Although it was a Chinese New Year festival, buyers and sellers from different ethnic backgrounds participated in the CSSYKL event. Thus, the CSSYKL is able to transform itself into a space transcending rural and urban as well as ethnic divides, from strictly a clan-based social institution but also a recreational and market space, creating “moment[s] of unity” as described by Shamsul Amri Baharuddin (2017). In the larger picture, this also suggests that this clan association, in particular, has evolved to adopt new social functions beyond just that of providing welfare for its immediate members. CSSYKL is one example of a historical building which functioned not only in the past as a community centre for the Chinese who migrated to Malaya in search of economic opportunity, but still retains its functions today as a gateway to maintaining links with Mainland China, especially in the economic dimension. Simultaneously, the heritage building also attracts tourists from all around the world, including those from China and local tourists themselves. It provides symbolic aesthetic meaning to the future of Kuala Lumpur’s development and enriches the local cultural expression in league with the Malaysian National Cultural Policy.

REFERENCES

Acs, Z. J., & Dana, L. P. (2000). Contrasting Two Models of Wealth Redistribution. Small Business Economics, 16, 63-74. [ Links ]

Al-Obaidi, K., Sim, L. W., Ismail, M. A., & Kam, K. (2017). Sustainable building assessment of colonial shophouses after adaptive reuse in Kuala Lumpur. Buildings, 7(4), 87. [ Links ]

Arabestani, M., & Edo, J. (2011). The Semai’s response to missionary work: From resistance to compliance. Anthropological Notebooks, 17(3), 5-27. [ Links ]

Askari, A. H., & Dola, K. B. (2009). Influence of building façade visual elements on its historical image: Case of Kuala Lumpur city. Malaysia. Journal of Design and Built Environment, 5(1), 29-40. [ Links ]

Azhari, N. F. N., & Mohamed, E. (2012). Public perception: heritage building conservation in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 50, 271-279. [ Links ]

Burgess, E. W. (1927). The determination of gradients in the growth of the city. Publications of the American Sociological Society, 21, 178-84. [ Links ]

Burgess, E. W. (1925). The growth of the city. In R. E. Park, E.W. Burgess & R. D. Mackenzie (Eds.), The City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Burgess, E. W. (1924). The growth of the city: an introduction to a research project. Publications of the American Sociological Society, 18, 85-97. [ Links ]

Cardosa, E. (2002). Heritage of Malaysia Trust Executive Director. Travel Times, 29 March - 4 April 2002. [ Links ]

Carstens, S. A. (1975). Chinese associations in Singapore society: an examination of function and meaning. Occasional Paper No. 37. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [ Links ]

Chan, S. C. (2003). Interpreting Chinese Tradition: A Clansmen Organisation in Singapore. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 5(1), 72-90. [ Links ]

Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Association. (2016). Glory Days Relived: 120 Years of Chan She Shu Yuen. Kuala Lumpur: Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Association. Retrieved from http://cssykl.com/ [ Links ]

Chan, J., To, H. P., & Chan, E. (2006). Reconsidering social cohesion: Developing a definition and analytical framework for empirical research. Social Indicators Research, 75(2), 273-302. [ Links ]

Cheng, E. W., Li, A. H., & Ma, S. (2013). Resistance, Engagement, and Heritage Conservation by Voluntary Sector: The Case of Penang in Malaysia. Modern Asian Studies, 48(3), 617-644. [ Links ]

Ch’ng, C. L. D. (1995). Sukses Bisnis Cina Perantauan. Latar Belakang, Praktek Bisnis dan Jaringan Internasional. Jakarta: Pustaka Utama Grafiti. [ Links ]

Dana, L. P., Etemad, H., & Wright, R. W. (2000). The global reach of symbiotic networks. In L. P. Dana (Ed.), Global Marketing Co-operation and Networks. Binghamton (pp. 1-16). NY: International Business Press.

Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center. (2015). Malaysia in Perspective. Retrieved from http://fieldsupport.dliflc.edu/products/cip/Malaysia/malaysia.pdf [ Links ]

Dick, H. W., & Rimmer, P. J. (1998). Beyond the third world city: the new urban geography of South-east Asia. Urban Studies, 35(12), 2303-2321. [ Links ]

Dümcke, C., & Gnedovsky, M. (2013). The social and economic value of cultural heritage: literature review. EENC paper, 1-114. [ Links ]

Ember, M., Ember, C. R., & Skoggard, I. (Eds.). (2004). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. [ Links ]

Malaysian Chinese Association. (2017). Eyeing Belt and Road business. Retrieved from http://www.mca.org.my/2/Content/SinglePage?_param1=03-092017-153499-09-201703&_param2=TS [ Links ]

Feilden, B. M. (1994). Conservation of Historic Buildings. Oxford, Boston: Butterworth Architecture.

Germani, G. (Ed.). (1973). Modernization, Urbanization, and the Urban Crisis. Somerset: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (2013). The Consequences of Modernity. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Hadi, A. S., Idrus, S., Shah, A. H. H. & Mohamed, A. F. (2010). Malaysian urbanization transition: From nascent, pseudo to livable mega-urban region. Malaysian Journal of Environmental Management, 11(1), 3-13. [ Links ]

Harding, A., & Blokland, T. (2014). Urban Theory: A Critical Introduction to Power, Cities, and Urbanism in the 21st century. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Hashim, A. E., Aksah, H., & Said, S. Y. (2012). Functional assessment through post occupancy review on refurbished historical public building in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 68, 330-340. [ Links ]

Hirschman, C. (1987). The meaning and measurement of ethnicity in Malaysia: an analysis of census classifications. The Journal of Asian Studies, 46(03), 555-582. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2056899 [ Links ]

Hirschman, C. (1976). Recent urbanization trends in Peninsular Malaysia. Demography, 13(4), 445-461. [ Links ]

Hribar, M. `., Bole, D., & Pipan, P. (2015). Sustainable heritage management: social, economic and other potentials of culture in local development. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 188, 103-110. [ Links ]

Hribar, M. `., & Lozej, `. L. (2013). The role of identifying and managing cultural values in rural development. Acta Geographica Slovenica, 53(2), 371-378. [ Links ]

Idid, S. Z. A. (1995). Pemeliharaan Warisan Rupa Bandar. Kuala Lumpur: Badan Warisan Malaysia. [ Links ]

Khalid, K. A. T. (2016). Patriotisme dan identiti: mitos warga tanpa bangsa. In R. Kiandee & S. Pandian (Ed.), Patriotisme Malaysia: Sejarah, Isu dan Cabaran (pp. 1-14). Pulau Pinang: Universiti Sains Malaysia. [ Links ]

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (2004). Intangible heritage as metacultural production. Museum International, 56(1-2), 52-65. [ Links ]

Kong, L. (2011). Sustainable cultural spaces in the global city: Cultural clusters in heritage sites, Hong Kong and Singapore. In G. Bridge, S. Watson (Eds.), The New Blackwell Companion to the City, Blackwell, 452-462. [ Links ]

Light, I. (1972). Ethnic Enterprise in America: Business and Welfare among Chinese, Japanese, and Blacks. Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Loewen, J. W. (1971). The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Long, D. G., & Han Q. M. (2008). Re-generating the cultural identity and social network abroad. Cambridge Journal of China Studies, 9(1), 35-47. [ Links ]

Lösch, A. (1965). The Economics of Location (2nd rev. ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Masron, T., Yaakob, U., Ayob, N. M., & Mokhtar, A. S. (2012). Population and spatial distribution of urbanisation in Peninsular Malaysia 1957-2000. Geografia-Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 8(2), 20-29. [ Links ]

Malaysia Tourism Centre. (2017). Launching KL Must Visit Attractions Trail Card. Retrieved from http://www.matic.gov.my/en/information/gallery/photo/291-launching-klmust-visit-attractions-trail-card-19-oktober-2017 [ Links ]

Makmur, M. (2018). The Chinese Clan Associations in Padang: A package of the ethnic tradition and the social-culture change in the era of globalization. Friendly City 4 ‘From Research to Implementation for Better Sustainability’ IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 126. [ Links ]

McGee, T. (2017). Managing and planning for urban sustainability in Malaysia: challenges for the twenty first century. International Conference on Sustainable Cities, Communities, and Partnerships for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 10 October 2017. [ Links ]

Ibrahim, M. A., Wahab, M. H. Shukri, M. S., & Sharif, M. R. M. (2017). Regenerating Pudu marketplace and urban identity. Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Technology. UTM Razak School of Engineering and Advanced Technology, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 10 October 2017. [ Links ]

Tamjes, M. S., Rani, W. N. M. W. M., Wahab, M. H., Che Amat, R., & Ismail, S. (2017). Governance of urban heritage - a review on adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Technology, UTM Razak School of Engineering and Advanced Technology, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 10 October 2017. [ Links ]

Nasar, J. L. (1994). Urban design aesthetics: The evaluative qualities of building exteriors. Environment and Behavior, 26(3), 377-401. [ Links ]

Ng, C. K. (2002). An Outline of the Recent Development of Clan Associations in Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.ihakka.net/DOC/An%20Outline%20of%20the%20Recent%20Development%20of%20Clan%20Associations%20in%20Singapore-%E5%90%B3%E6%8C%AF%E5%25 [ Links ]

Ooi, K. G. (2015). Disparate identities: Penang from a historical perspective, 1780-1941. Kajian Malaysia, 33(2), 27-52. [ Links ]

Overseas Chinese in the British Empire. (2011). Chan Sow Lin. Retrieved from http://overseaschineseinthebritishempire.blogspot.my/2011/12/chan-sow-lin.html

Pahl, R. E. (1991). The search for social cohesion: from Durkheim to the European Commission. European Journal of Sociology/Archives Européennes de Sociologie, 32(2), 345-360. [ Links ]

Purcell, V. (1967). The Chinese in Malaya. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Robbins, P. T. (2001). Sociology of Development. University of London External Programme Subject Guide. London: University of London. [ Links ]

Roda, J. M., & Ahmad, I. (2010). From the “Surat Sungai” to the world timber markets: the role of Malaysian Chinese transnational firms in the local, regional, and globalintegration. Retrieved from http://agritrop.cirad.fr/564678/1/document_564678.pdf [ Links ]

Rostow, W. W. (1960). The Stages of Growth: A Non-communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 4-16.

Said, S. Y., Aksah H., & Ismail, E. D. (2013). Heritage conservation and regeneration of historic areas in Malaysia. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 105, 418-428. [ Links ]

Shamsul, A. B. (2013). Masyarakat Malaysia Menjelang Tahun 2020: Memperkukuh Kesepaduan Sosial ke Arah Mencapai Matlamat Perpaduan Nasional. Kertas Kerja Untuk Seminar Pertemuan Profesor-Profesor, Anjuran Majlis Universiti Islam Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, 19-20 Januari 2013. [ Links ]

Shamsul, A. B., & Yusoff, A. Y. (2014). Unity, Cohesion, Reconciliation: One Country, Three Cherished Concepts. Kuala Lumpur: Institut Terjemahan Buku Malaysia. [ Links ]

Shuid, S. (2004). Urbanization and housing in Kuala Lumpur city centre: issues and future challenges. Proceedings of the 19th EAROPH World Planning and Housing Congress, Melbourne, Australia, 19 - 22 April 2004. [ Links ]

Spencer, H. (1864). The Principle of Biology. London: Williams and Morgate. [ Links ]

Sun, W. (2005). Media and the Chinese diaspora: Community, consumption, and transnational imagination. Journal of Chinese Overseas, 1(1), 65-86. [ Links ]

Ujang, N. (2014). Place meaning and significance of the traditional shopping district in the city centre of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR, 8(1), 66-77. [ Links ]

Tan, S. K., Tan, S. H., Kok, Y. S. & Choon, S. W. (2018). Sense of place and sustainability of intangible cultural heritage-The case of George Town and Melaka. Tourism Management, 67, 376-387. [ Links ]

Turok, I., & Bailey, N. (2004). Twin track cities? Competitiveness and cohesion in Glasgow and Edinburgh. Progress in Planning, 62(3), 135-204. [ Links ]

UN-Habitat (2013). State of the world’s cities 2012/2013: Prosperity of cities. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (UNESCO). (2016). Culture, Urban Future: Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development. Paris: UNESCO.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024-1054. [ Links ]

Walsh, K. (1992). The Representation of the Past: Museums and Heritage in the Post-modern World. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wong, B. (1987). The role of ethnicity in enclave entrepreneurs: a study of the Chinese garment factory in New York City. Human Organization, 66(2), 120-30. [ Links ]

Yaakob, U., Masron, T., & Masami, F. (2010). Ninety years of urbanization in Malaysia: a geographical investigation of its trends and characteristics. J Ritsumeikan Soc Sci Humanit, 4(3), 79-101. [ Links ]

Yen, C. H. (1981). Early Chinese clan organizations in Singapore and Malaya, 1819-1911. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 12(1), 62-91. [ Links ]

Yeoh, B. S., & Kong, L. (2012). Singapore’s Chinatown: Nation building and heritage tourism in a multiracial city. Localities, 2, 117. [ Links ]

Acknowledgements

This research work is supported by the Ministry of Education of Malaysia under Grant Number FRGS/1/2018/WAB12/UKM/02/1 (Superdiversity Networks: Cantonese Clan Associations in Malaysia as Transnational Social Support System). Part of this paper will also be presented in an upcoming conference.

Recebido: março 2019. Aceite: janeiro 2020.