I. Introduction

Given the growing competitiveness between tourist destinations and the claim to capture the interest of companies, entrepreneurs, and investors, who aim for more profitable regions, the territories transform and adapt, to achieve this purpose (Pereira et al., 2013). It is crucial that entrepreneurs perceive and believe in the potentialities of the regions. This is a precondition in their choices to settle and implement their projects and company. This dynamic is essential to the development of territories and of tourism.

Entrepreneurship is therefore a fundamental process for the competitiveness and innovation of tourist regions. Particularly, considering the diverse and profound implications of the pandemic generated by COVID-19 in tourism destinations, entrepreneurship becomes especially relevant, as it manifests itself as an important instrument of creativity, empowerment, and innovation (Long, 2017). Tourism entrepreneurs therefore play a key role in the attractiveness, authenticity, and competitiveness of destinations (Dias et al., 2021). However, research on this topic is still limited and tourism entrepreneurs represent a group that has been little studied in the literature. Furthermore, to date, there is little research covering how tourism entrepreneurs engage with the uncertainty caused by long-lasting crises such as the pandemic of COVID-19 (Dias et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022).

In addition, it is important to increase and deepen knowledge about the motivations of entrepreneurs in the tourism sector and about the attributes, intrinsic factors, or features that they value in the territories and that drive them to invest (or not) in tourist destinations. This article addresses this issue considering the Central Region of Portugal, with two main research questions: What drives tourism entrepreneurs to invest in the Centre Region? Which are the Centre Region destination attributes or factors that influence entrepreneurs’ choice to invest and innovate? Thus, the aim is to understand the motivations of entrepreneurs in the Centre Region, for which a self-administered survey was applied. The results were analyzed for content, reliability, R-rating and internal consistency of the scale. Differences in responses between groups were tested using MANOVA.

From the theoretical point of view, the present study contributes to: (i) broaden knowledge within the scope of crisis management, and (ii) extend the scarce scientifically gathered knowledge about the specific group of tourism entrepreneurs. From a practical perspective and considering the pandemic crisis we are going through, the results allow us: (i) to better understand the motivations of tourism entrepreneurs, and (ii) to identify their needs and expectations, so that we can implement strategies and policies adjusted to the reality and current situation, which promote the revitalization of the business fabric and boost entrepreneurship in tourism destinations in a post-pandemic period.

Finally, recent research (Dias et al., 2021, 2022; Global Entrepreneurship Monitor [GEM], 2019) has shown that Portuguese entrepreneurial indicators (entrepreneurial behavior and attitudes) are equal or even higher than the global European Union (EU) countries average hence the results of this study are of interest to researchers and policy makers in other countries.

To achieve the above-mentioned objectives, this article is organized in five sections. After this introduction, a literature review section on entrepreneurship and tourism and motivations for tourism entrepreneurship is presented. The third section includes the methodology used to collect and analyse the data. Further, the results obtained will be described and discussed. Finally, the article ends with the most important conclusions, theoretical and practical contributions, limitations, and avenues for further research.

II. Literature review

1. Entrepreneurship and tourism

In Schumpeter’s (1982) view, the concept of entrepreneurship is closely linked to innovation, reflected in the introduction of new products, new services or combinations of resources, different production and organizational methods and opening to new market niches (Araújo & Júnior, 2018; Conceição & Costa, 2017). Santos et al. (2013) add that the process of entrepreneurship presupposes disruption with the external environment, in a search for new products, new markets and new sources that add value to the customer experience. Entrepreneurship thus presents itself as a fundamental process to boost the development of the territory (region or country), induced by the entrepreneur’s aptitude to perceive opportunities and ability to innovate (Araújo & Júnior, 2018; Chim-Miki et al., 2016).

Many territories, which aim to attract entrepreneurs, are linked to the definition of strategies that stimulate a culture linked to the development of incentive programmes, which bring together educational, cultural, academic, and entrepreneurial initiatives (Jardim, 2019). They also provide services that boost business start-ups or facilitate the aid and support of growing businesses (Brand et al., 2021). These initiatives are implemented with the purpose of designing beneficial ecosystems for the development of new products and the settlement of people, organizations, and companies, in favor of the economic and social growth of the territory, in general (Jardim, 2019).

Knowing that tourism activity takes place in tourist destinations and that it imperiously relies on their intrinsic characteristics, such as resources and tourist attractions, entrepreneurship can be one of its drivers of evolution. In this sense, according to Araújo and Júnior (2018), entrepreneurship for its specificities (ability of the entrepreneur to identify and seize opportunities, take risks and innovate), allied to the tourism sector, can be translated into a way to add value to the tourism product (new processes and methods, innovative and creative trends), but also trigger the development of the region (Chim-Miki et al., 2016; Jardim, 2019; Santos et al., 2013).

Similarly, the pandemic generated by COVID-19 combined with the globalization and massification of information and knowledge, have led to tourists being much more active and operative in the organization of their trips and more considerate in terms of risk and safety. Consumers, with the proliferation of new communication technologies, are increasingly more discerning in their choice of experiences (Pappas & Glyptou, 2021; Villacé-Molinero et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2021). Tourism demand is “confined”, but it has not disappeared. On the contrary, several studies point to the increased value of tourist travel, in a more selective, specific way and with a greater concern for sustainability (Ateljevic, 2020; Bacq & Lumpkin, 2020; Dias et al., 2021; Gossling et al., 2020; Rubio-Mozos et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2021). Thus, if the adaptation to the digital and even the virtual was a concern of 2020 (Breier et al., 2021), human capital, flexibility, creativity, and sustainability are the challenges from 2021 onwards.

Traditional volume growth models seem to be driven by large enterprises that appear not to fit a new logic of development emerging with COVID-19. Innovation and skills should be at the top of priorities for the revitalization of small tourism businesses (Dias et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019a; Yachin, 2019). The pandemic has accentuated some of the sector’s vulnerabilities, notably in business support (lack of strategy and long-term policies) and human capital (precariousness and low wages), providing striking lessons for the tourism industry, policymakers, and researchers on the effects of global change. The COVID-19 crisis should thus be seen as an opportunity to critically reconsider the growth trajectory of tourism and act on the most vulnerable dimensions (Gossling et al., 2020).

As agents of change, entrepreneurs, are the ones best positioned to respond to these challenges, adding value to tourism destinations, boosting job creation, diversity of tourism supply, efficiency in the use of resources and attracting visitors (Araújo & Júnior, 2018). In a post-pandemic context, entrepreneurs may assert themselves as a vibrant instrument for tourism development (Kline et al., 2020) and a pillar for destination differentiation (Dias et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, it is important to note that entrepreneurs seek in this process, equally, reward and satisfaction, which may be of different order (Araújo & Júnior, 2018; Comparin, 2017). Conceição and Costa (2017) refer that the archetype of entrepreneurship is differentiated, even in countries with similar economic growth rates, which explains that there are several factors that influence this process. Tourism entrepreneurs are one of the most representative groups of small-scale enterprises, with their own specificities that distinguish them from investors in other areas, which justifies giving them special attention (Dias et al., 2022).

In Portugal, a few studies related to the topic under analysis have been developed. In this scope, Portuguese researchers have mainly focused on entrepreneurship in rural areas (Bakas et al., 2019; Ferreira et al., 2019), especially in low density areas (Dinis, 2021) or protected natural areas (Silva et al., 2022), with emphasis on the northern region of Portugal (Marques & Cunha, 2013). Furthermore, there has been research on education and entrepreneurship (Banha et al., 2022; de la Cruz del Río-Rama et al., 2017; de Pinho, 2021; Pinto Borges et al., 2021), particularly in the field of attitudes and skills towards entrepreneurship (Castro & Ferreira, 2019). Therefore, it is important to emphasize that no study focuses on the Central Region of Portugal.

2. Motivations for tourism entrepreneurship

The tourism entrepreneur faces a still complex and dynamic process, not only by the panoply of business opportunities that the market allows (Dias et al., 2021, 2022), in various subsectors of products and services (accommodation, catering, recreational activities, transport, among others), but also by the volatility of the needs and expectations of tourism consumers, in permanent and constant change (Long, 2017). It is important not to forget the rigidity or reduced flexibility of the intrinsic characteristics of territories or tourist destinations.

In the whole decision process, whether to become a tourism entrepreneur, the intrinsic factors of the individual are relevant, such as age, entrepreneurial skills, leadership ability, independence, self-confidence or fearlessness (Cebola & Proença, 2018). Not being afraid of failure or having the courage to take risks, as well as academic and professional experience, are personal skills that acquire a leading role in the whole process (Pereira et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2019b). At the same time, dissatisfaction with dependent employment, the search for personal fulfilment or circumstances such as unemployment, can be facilitating bridges for entrepreneurship because they lead the individual to create their own opportunities (Wang et al., 2019b). In addition, other factors such as encouragement from family and friends (Pereira et al., 2013) or partners (Tajeddini et al., 2020) may also influence this decision making.

In the same sense, factors extrinsic to the individual also influence the decision to become an entrepreneur, facilitating or restricting an entrepreneurial climate (Kline et al., 2020). Dynamic, creative, and enabling environments for the development of ideas, provided with the necessary resources for their implementation such as infrastructure, networks and financial support are other determinants that influence decision making (Tajeddini et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019b). Entrepreneurship can also be the consequence of national measures and conditions that are conducive (or not) to investment-friendly environments, the understanding of needs and a set of situations conducive to the emergence of opportunities inherent to the context.

Specifically, in the case of tourism entrepreneurs, Hallak et al. (2015) points out that territorial identity influences their self-efficacy, i.e., if individuals identify with the beliefs, values, characteristics, specificities, and potential of the region, they stimulate their own ability to achieve goals and their personal entrepreneurial skills, as well as a closer relationship with the community. The attractiveness of destinations, existence of tourism resources, community characteristics and economic dynamics of the context, are particularly relevant in the motivation of the tourism entrepreneur (Araújo & Júnior, 2018). Dias et al. (2022) highlight that the main difference is the approach to performance. That is, while entrepreneurs in other areas seek financial performance, tourism entrepreneurs target other goals associated with lifestyle, environmental or social preservation and even identification with the project development site itself (Ateljevic & Doorne, 2000; Wang et al., 2019b). For example, Hjalager et al. (2018) argue that these entrepreneurs are driven by opportunities rather than needs. A possible justification stems from a kind of democratization of access to the sector (Bosworth & Farrell, 2011; Ioannides & Petersen, 2003), i.e., many of these entrepreneurs are attracted to tourism by the existence of scarce barriers, such as low investments or low need for expertise to start the business (Dias et al., 2021). As a result, these entrepreneurs traditionally have limited experience, lacked specific skills and have modest resources (Dias et al., 2022, Marchant & Mottiar, 2011). In the same vein, other research developed in Portugal by Dinis (2021) aiming to understand whether tourism entrepreneurship is a possibility of income for immigrants, attested that lifestyle motivations are not homogenous. The author reveals there is a distinction between socio-ideological motivations (strong commitment with sustainability and connection with nature) and better-quality of life motivations (self-centered, related with the individual concern of searching for a better way of living).

III. Methodology

1. Preliminary considerations

The Centre of Portugal Tourism Board (TCP) promotes an annual entrepreneurship contest called “José Manuel Alves Tourism Entrepreneurship Contest” (Entidade Regional de Turismo do Centro, 2020). This initiative aims to financially support innovative projects in the tourism sector, to be implemented in the Centre Region (CR), Portugal. The “Tourist Investment Support Centre” (NAIT), integrated in the TCP, promotes dissemination/clarification sessions aimed at entrepreneurs and other entities, who show interest in learning about entrepreneurship practices, as well as developing innovative projects. NAIT is under the Administrative and Financial Department of TCP and has as main responsibilities:

monitor the regional and sub-regional tourism supply;

promote tourism information regarding business activity to investors or potential investors;

carry out personalized service to tourism investors and monitor tourism projects;

technically support the municipalities of the CR;

manage and promote the Tourism Activity Observatory;

implement the Quality Management System (QMS) according to ISO9001;

suggest the establishment of partnerships with universities and polytechnics considering education, training and research;

encourage the development of studies and projects that highlight the evolution of the tourism sector and market trends, and;

promote tourism entrepreneurship in the region.

The target population of this study includes entrepreneurs supported by these two entities, regardless of the stage of development of their projects, according to the following criteria: (i) no tourism activity started, as regards licensing, infrastructure construction and marketing, although the company may already be established; (ii) having participated in any of the NAIT initiatives.

The year 2015 represents a turning point, with the rebranding of the Turismo do Centro brand, being the reason why it was intended to know the motivations of the entrepreneurs to invest in the CR, who had contact with these Entities from that year onwards. The CR is one of the largest tourism regions in the country, comprising a group of 100 municipalities and eight intermunicipal communities. It has a wide variety of resources and attractions, and a diversified tourist offer. In recent years it has evolved positively in terms of attractiveness and tourism figures, having proved to be an interesting alternative to other more frequented national destinations during the restrictions imposed by the pandemic (Centre of Portugal Tourism Board, 2021). Thus, since there are no studies on tourism entrepreneurship in this region, this knowledge gap was addressed in the present research.

2. Sample

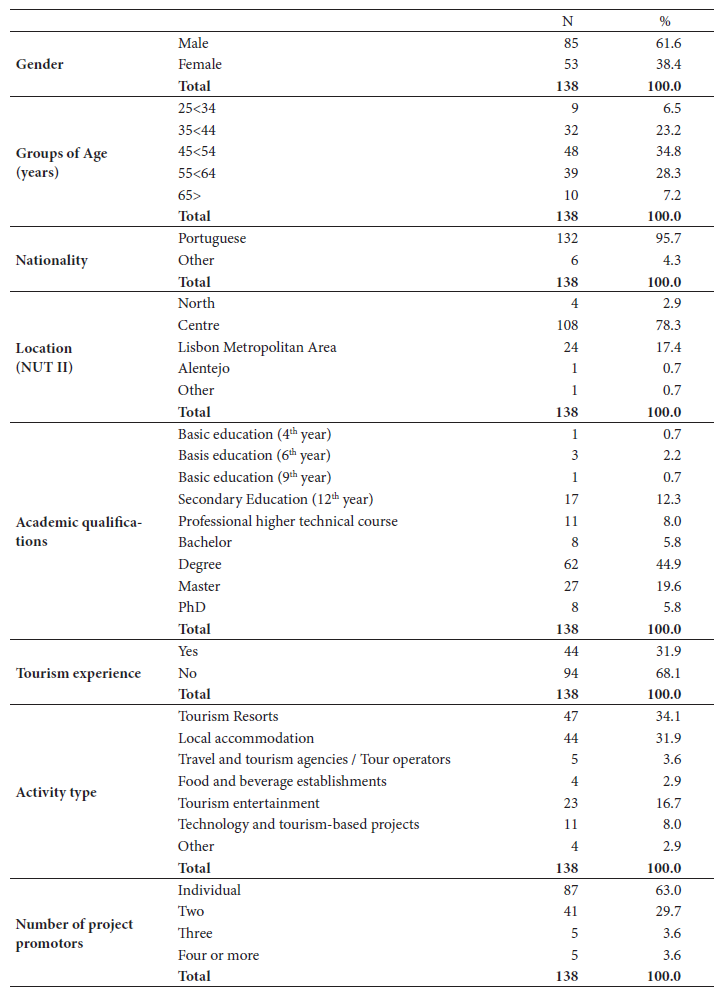

In the period 2015-2020, 201 participants in the Contest and 1395 individuals who had contacts with NAIT were identified. The sample was collected from a universe of 1596 subjects, consisting of 138 valid answers (N=138), according to the assumptions of non-probability sampling by convenience and intentional sampling (Aires, 2011; Coutinho, 2015; Lopes, 2005). Although respondents may come from other regions of the country (18.0%) or even from abroad (1.4%), they are predominantly located in the CR (77.5%), following the principle of entrepreneurs’ identification with the identity of the territory where they intend to implement their projects (Hallak et al., 2015) (table I).

Most respondents were male (61.6%) and between 45 and 54 years old (34.8%). There were other nationalities besides Portuguese (95.7%), which were grouped in the category “Others” (4.3%), as they represent approximately one individual per country, namely: Brazilian, Italian, French, Angolan, Belgian and Swiss. In terms of academic qualifications, the majority of respondents have higher education qualifications, at Bachelor’s level (5.8%), Degree (44.9%), Master’s (19.6%) and Doctorate (5.8%). The predominant degrees were in economics, business management and administration (18.1%), hotel management, tourism, and catering (17.4%) and engineering (11.6%). Regarding experience in tourism before the beginning of the project, 94 of the respondents had no experience (68.1%) and 44 (31.9%) had already worked in this area. Individual projects (63.0%) or projects carried out by two entrepreneurs (29.7%) predominate. The investments are mainly in tourism enterprises (34.7%), local accommodation (31.9%) and tourist entertainment (16.7%) (table I).

For question three of the survey only the respondents who continued with their project answered, therefore the results of this study refer to the opinion of 121 subjects.

In brief, the CR entrepreneur is male (61.6%), have higher education qualifications, but has no experience in tourism, only a few had already worked in tourism. They are mainly investing in individual projects or with only two entrepreneurs, particularly in the hospitality, local accommodation and tourist entertainment sectors.

3. Instrument

A self-administered questionnaire was constructed to learn about tourism entrepreneurs (Tourism entrepreneurs in the Central Region/Empreendedores turísticos da Região Centro (ETUR C), since research on this domain is scarce and no valid instruments were found for this specific purpose, the creation of the motivational scale was based on several previous works (Dias et al., 2021; GEM, 2019; Long, 2017; Wang et al., 2019a.)

The questionnaire comprises 31 questions and is divided into six parts, namely: (i) introduction; (ii) sociodemographic variables; (iii) project characterization; (iv) current situation of the project; (v) motivation to entrepreneurship; and (vi) Turismo do Centro brand. This study focuses on the analysis of the results of the scale “Motivation to undertake entrepreneurship in CR” (ME), composed of 16 items. It was assessed by a five-point Likert scale, ranging from Not at All Important (1) to Extremely Important or Decisive (5) (Cunha, 2007; Dalmoro & Vieira, 2013; Thayer-Hart et al., 2010). Gorsuch’s (1983) assumptions regarding the sample size were respected, with a ratio of 7.6 (i.e., 121 participants/16 items). The items reflect extrinsic facilitators (Kline et al., 2020; Tajeddini et al., 2020) and intrinsic facilitators of the entrepreneur (Pereira et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2019b).

4. Procedures

The ETUR C was completed online in the Google Forms platform, and an invitation to complete it was sent through the NAIT’s own email. The invitation explained the research context, topic, and objectives of the study (Brewerton & Millward, 2001). The period for sending the surveys began in January and ran until May 2021, with re-submissions in February and May, making a total of 138 responses. All surveys were considered valid, since the questions had to be answered, an aspect controlled by the computer application itself. Whenever requested, additional clarifications were provided to respondents. Information on the objectives of the study, completion instructions, the voluntary and anonymous nature of the participation, and the guarantee of individual data confidentiality were also in the instructions, guarantying ethical requirements.

5. Data analysis

The analyses were completed using IBM SPSS software. Frequencies were examined in order to eliminate items without variation and outliers analyzed according to Mahalanobis squared distance (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). The normality of the variables was assessed by the coefficients of skewness (Sk) and kurtosis (Ku), and no variable presented scores violating normal distribution (|Sk|<2; |Ku|<3). The central tendency measures indicate that the mean scores are close to the median and mode in all items. Dispersion measures reveal that the tendency to respond to items is distributed across almost all options on the scale.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The PCA assumptions were tested through the sample size (minimum ratio of five subjects per item; Gorsuch, 1983), normality and linearity of the variables, factorability of R, and sample adequacy (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Since we intend to retain independent factors, we have chosen VARIMAX rotation with Kaiser’s normalization.

Reliability was calculated by Cronbach’s alpha (Nunnally, 1978), considering acceptable an α>0,70 (Hair et al., 2009). The composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE) for each factor were evaluated as described in Fornell and Larcker (1981).

The assumptions of Field (2006) and Mayers (2013) for MANOVA were checked for: (i) independence of the observations; (ii) randomness of the sample; (iii) multivariate normality; (iv) homogeneity of the variance-covariance matrices (Levene and Bartlett’s Sphericity tests). The absence of multicollinearity was also observed (Montgomery et al., 2006).

IV. Results and discussion

1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (PCA)

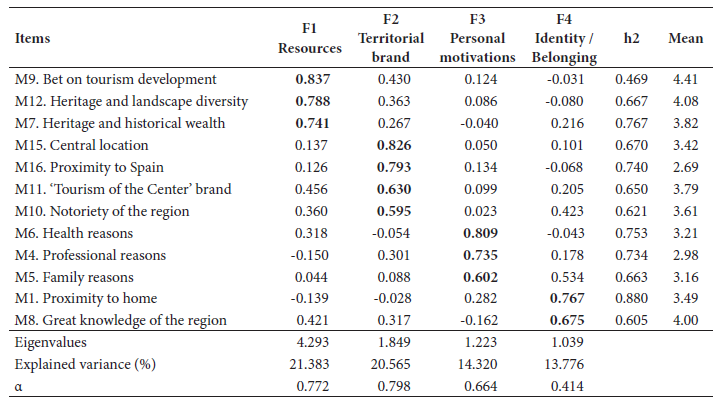

Table II presents the communalities, eigenvalues, and explained variance for the rotated component matrix of the seven iterations. Previously, the requirements for reliable interpretation of PCA were assured: ratio of 7.6 subjects/item; correlation matrix differs from the identity Bartlett’s test (X2(66)=517.163, p<0.001) and anti-image (matrix scores between 0.736 and 0.397 (highest score outside the diagonal of -0.206)); and the sampling was adequate (KMO=0.795).

Table II PCA and reliability (α) of the ‘Motivation to invest in the CR’ scale: factor loadings, communalities (h2), eigenvalues, and explained variance (%).

The construct validity of the “Motivation to invest in the CR” scale revealed four factors, with a total explained variance of 70.05%. The overall reliability is very good (0,807) as well as for the factors F1 (0.772) and F2 (0.798); it’s good for F3 (0.664) and acceptable for F4 (0.414) (table II). F4 was considered acceptable, based on the literature review (Gorsuch, 1983; Maroco & Garcia-Marques, 2006), as several research highlighted the importance of lifestyle and identification with the project development site itself (Ateljevic & Doorne, 2000; Hjalager et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019b), as one of the main motivations that differentiates tourism entrepreneurs from others. Thus, these results should be interpreted with caution.

The factors F1 “Resources” and F2 “Territorial brand”, so named for grouping items that refer to the tourism potential of the region, identify the extrinsic motivations of the entrepreneur at the level of opportunities (Kline et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019a) and the needs of the territory (Ateljevic & Doorne, 2000; Hallak et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019b). In the CR, entrepreneurs highlight the commitment or “bet on tourism development” (mean 4.41) and “heritage and landscape diversity” (mean 4.08) as the most important attributes or features considering the destination resources, and “Tourism of the Center’ brand” (mean 3.79) and “notoriety of the region” (mean 3.61) as significant features in the context of the destination territorial brand. This is aligned with the literature, since several authors stated that local development dynamics, resources, location, and brand awareness emerge as the conditions that most motivate tourism entrepreneurs to invest in their businesses (Ateljevic & Doorne, 2000). In this sense, creating a more favorable business environment requires debureaucratisation, training and rethinking the tourism development model to integrate more sustainable pathways for resources. And, simultaneously, re-evaluate marketing strategies considering segments or niches that enjoy value-added tourism products (Gossling et al., 2020), more aligned with the supply of small tourism enterprises (Dias et al., 2021).

At the level of intrinsic motivations of the tourism entrepreneur, the factors F3 ‘Personal motivations’ and F4 “Identity/Belonging” stand out. Specifically, “health reasons” (mean 3.21) in personal motivations and “Great knowledge of the region” (mean 4.0) in the context of identity motivations or feelings of belonging. These findings corroborate the literature since the identification with the territory (Kline et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2013) and personal, family, and social fulfilment (Araújo & Júnior, 2015; Chim-Miki et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019a) also stand out. Lifestyle and prestige (Araújo & Júnior, 2018; Bosworth & Farrell, 2011; Hall & Rusher, 2004; Hallak et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019b) seem to be aspects that do not influence the investment options of this group of respondents. Tourism entrepreneurs have local attachment or emotional ties to the places where they intend to implement their business ideas. They identify with the territory or its potential and seek to develop their projects in reciprocity of benefits (for themselves and for the territory) (Araújo & Júnior, 2016; Pereira et al., 2013). All these motivations condition the decision making of the tourism entrepreneur and influence the development of their business. However, the literature highlights the so-called external factors, associated with the conditions of the context, as those that may be preponderant in the decision of tourism entrepreneurs to set up and evolve their businesses, in territories with which they identify. This dimension is equally important for tourism entrepreneurs in the CR.

2. Multivariate analysis (MANOVA)

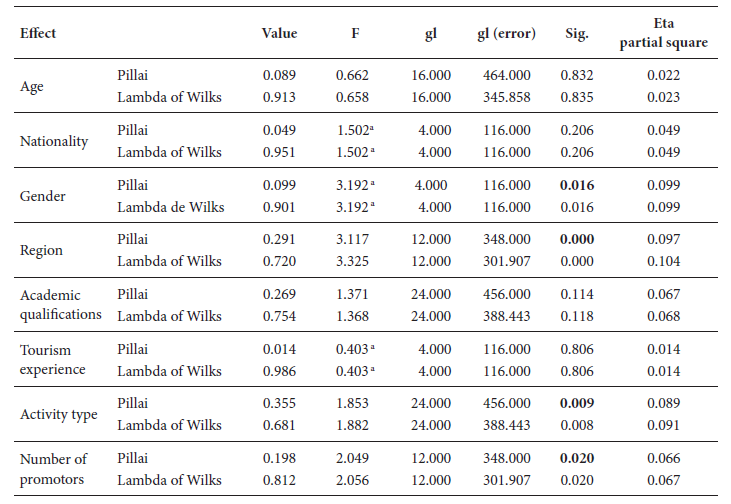

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was carried out to verify differences in participants’ perceptions of the predominant factors that influenced their decision to invest in CR, according to the independent variables (IV): age, nationality, gender, region, education, experience in tourism, type of activity and number of project promoters. The dependent variables (DVs) were the mean scores of the factors of motivation to undertake. When statistically significant differences in the response between groups were found, we also analyzed the univariate effect of the variables (ANOVA), reducing the emergence of type I errors in the study (Field, 2006).

The “Pillai screening” and “Wilks’ Lambda test” were applied to ascertain the homogeneity of variances between groups. According to Mayers (2013), the “Lambda of Wilks” test is the most recommended test to analyze statistically significant differences in more than two groups of independent variables, considered simultaneously. Heterogeneity and a significant multivariate effect were identified in IVs gender (λ=0.901 F(4, 116)=3.192, p<0.05), region (λ=0.720 F(12, 301.907)=3.325, p<0.05), activity type (λ=0.681 F(24, 388.443)=1.882, p<0.05) and number of project promoters (λ=0.812, F(12, 301.907)=2.056, p<0.05) (table III).

3. Univariate analysis (ANOVA)

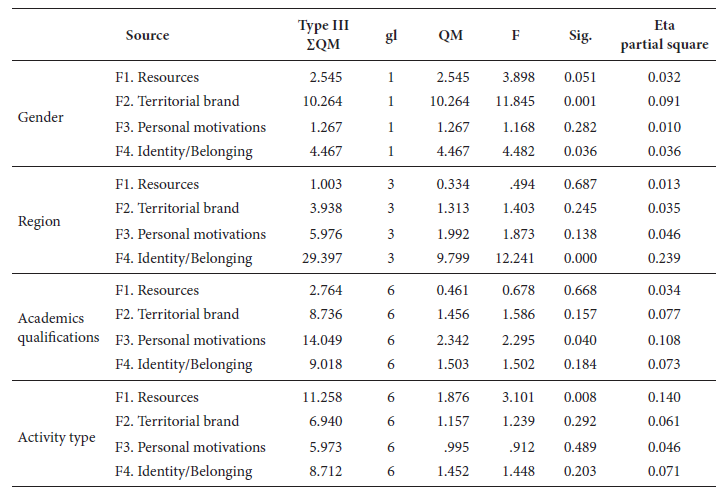

The difference in the perception of what motivates entrepreneurs to invest in CR in the groups that showed response variability in the previous analyses (table IV) was tested through ANOVA by taking the mean factor scores. Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) were found between:

people with different genders, concerning the factors Territorial brand (F2) [F(1.119)=11.845 p=0.001] and Identity/Belonging (F4) [F(1.119)=4482 p=0.036], with men valuing the destination brand more (sig=0.001), as well as identification with the territory (sig=0.036);

entrepreneurs coming from different regions and “Identity/Belonging” (F4) [F(3, 117)=12.241, p=0.000] and investors qualifications and “Personal motivations” (F3) [F(6,114)=2295 p=0.040], with no particular group standing out;

activity type to invest and Resources (F1) [F(6,114)=3.101 p=0.008], noting that entrepreneurs intending to invest in tourism entertainment/animation projects are the ones who most highlight the importance of the resources (sig=0.21).

V. Concluding remarks

In the current moment we are living, in which we all hope and pray that it will be “post-pandemic” or “post-COVID-19”, it is urgent to invest, not only in health security, but in the recovery of confidence and interest of all stakeholders involved in tourism activity. The positioning of destinations will only emerge strengthened from the pandemic crisis if the tourism industry reacts quickly to the transformations required by the new normal and collaborates with entrepreneurs in creating new and innovative solutions. In this context, knowing and understanding tourism entrepreneurs, especially what drives them to invest, i.e., their motivations, is essential.

This research aims to answer this pressing question and allows us to verify that tourism entrepreneurs in the CR are motivated by extrinsic and intrinsic factors, corroborating the literature review carried out.

The external motivations identified are the ‘Resources’ and the ‘Territorial brand’, placing emphasis on the enhancement and preservation of tourism resources (natural and cultural, material and immaterial) and the development and promotion of a cohesive territorial brand aligned with the values of the territories and their communities. It is therefore up to the territorial managers and the national, regional, and local authorities (DMOs) to outline strategies, financial and non-financial support, aimed at creating this favorable environment for the development of entrepreneurship in tourism, so that entrepreneurs set up their businesses and make their investments (Araújo & Júnior 2018).

At the internal level (of the individual), “Personal motivations” and “Identity/Belonging” were identified as the main motivations of tourism entrepreneurs. Health, professional and family reasons were the most indicated as justification for investment. In other words, tourism entrepreneurs seek a new lifestyle and, not only develop an idea, but also change their lives, seeking reward or satisfaction, not only in economic success and well-being, but simultaneously in a greater contact with nature, spiritual connection or overall quality of life (Kline et al., 2020). These entrepreneurs have been increasing and are called “lifestyle entrepreneurs” (Araújo & Júnior, 2018). Because of this drive, many leave their established careers behind and become social entrepreneurs, community leaders, activists, volunteers and often establish their own transformative tourism businesses (Ateljevic, 2020). In addition, the choice of tourism destination for investment is also based on feelings of belonging or proximity to what they consider “home”. In other words, they favor personal, intimate, or family preferences over economic ones and prioritize investments in places with characteristics related to their values (Araújo & Júnior, 2018; Chim-Miki et al., 2016).

Finally, it was found that men are most tourism entrepreneurs and those who most value the brand of the destination and who most identify with the territory where they intend to operate. In addition, it was found that, in the CR, individual projects or projects carried out by only two entrepreneurs predominate and that the investments focus, above all, on accommodation and tourist entertainment. These results open some lines of future research, such as, their comparison in regional, national, and international terms and even longitudinally. Another area to deepen in investigative terms will be the identification of the type of support to be provided to entrepreneurs and tourism entrepreneurs, since the funds that Portugal and the European Union have had at their disposal to stimulate the industry have privileged the areas of technological innovation and internationalization (Dias et al., 2021). However, in the post-pandemic context, it is necessary to understand whether this is the most appropriate type of support.

In methodological terms, the approach does not allow generalizations, which is a limitation of the study, but it does allow relevant conclusions to be drawn, indicating theoretical and practical implications.

VI. Research implications

At present and considering the pandemic factor, entrepreneurs and destinations must prepare themselves to respond adequately to the new challenges that are imposed (Gossling et al., 2020). As suggested by Bacq and Lumpkin (2020), the crisis offers entrepreneurs the opportunities to capitalize on efforts to develop innovative solutions, and destinations a possibility to transition to a new tourism era.

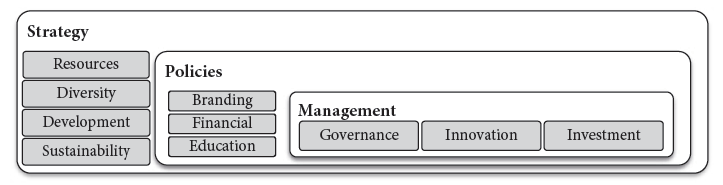

In this line of thought, in theoretical terms, the identification of the motivations of tourism entrepreneurs in a pandemic context allows to increase knowledge in the field of crisis management and also to expand the knowledge about the specific group of tourism entrepreneurs, which is proved, through this article, to have characteristics that distinguish them from other entrepreneurs. In practical terms, this research allows us to recommend that destinations, particularly national, regional, and local DMOs, should promote tourism entrepreneurship and aggregate a set of determinants that favor this practice and that are summarized in figure 1.

It is therefore essential that DMOs establish strategies based on the valorization of tourism resources and on the investment in diversity of tourism destinations, supported by sustainable development philosophies. Tourism entrepreneurs confirm that the diversity of tourism resources is the basis for the creation of tourism products and services and supports the identity of the territory. Moreover, they advocate their continuous enhancement supported by advanced sustainable development forms, responding not only to conservation and preservation prerogatives, but also to post-pandemic tourist consumer behavior trends. On the other hand, they suggest that implementation policies should be directed towards marketing, specifically destination branding, strengthening the image and identity of tourist destinations, as well as financial incentives to support innovative solutions and the education and training of their human capital. Finally, from the perspective of tourism entrepreneurs, tourism destinations management is crucial to their decision making, expecting concrete actions to promote and foster governance, innovation, and investment.

In short, knowing the factors that motivate the development of entrepreneurship (internal and external) it is possible to develop more appropriate strategies and policies to support new businesses or encourage existing ones to innovate and grow. Simultaneously, it becomes easier to guide public and private investments. And, on the other hand, higher education institutions and other training initiatives can develop more targeted educational programmes.

Author contributions

Andreia Moura: Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - preparation of original draft; Writing - proofreading and editing; Visualization; Supervision. Maria do Rosário Mira: Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - preparation of original draft; Visualization; Supervision. Ana Cristina Ferreira: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Research; Resources; Data curation.