1. INTRODUCTION

Since the 1990s, the theme of sexuality1 in education has gained prominence with the creation of the National Curriculum Parameters (PCN), which should be proposed in various disciplines (Moizés & Bueno, 2010). The PCN are guidelines for curricular reforms implemented in elementary education (Secretaria de Educação Fundamental do Brasil, 1998). In addition, according to Gava and Villela (2016), the Statute of Children and Adolescents, the commitments made by the Brazilian government in international documents related to the rights of women and youth, the challenge in dealing with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, and the rise in teenage pregnancy led to the legalized promotion of sex education (SE)2 in the 1990s (Gava & Villela, 2016; Ministério da Educação do Brasil, 1990).

Nowadays, the PCN proposal has been replaced by that of the Common National Base Curriculum (BNCC). However, in its latest version, approved in December 2017, the BNCC excludes gender issues due to the efforts of lawmakers and conservative groups in Brazil to suppress holistic and comprehensive approaches to education on gender and sexuality in primary and secondary public schools (Dias & Sposito, 2021). Teachers must address these issues to answer students’ questions and to comply with federal and state laws and policies that mandate comprehensive SE instruction (National Curriculum Guidelines for Elementary Education [Ministério da Educação do Brasil, 2013] and Technical Note n.º 32/2015 - CGDH/DPEDHUC/SECADI/MEC [Ministério da Educação do Brasil, 2015]).

In a systematic review, Flora et al. (2013) pointed out that few studies have evaluated SE interventions in terms of knowledge, attitude, and behavior. For example, the authors discovered only two studies in Brazil, both of which had methodological flaws.

In a study conducted by Sfair et al. (2015) on 25 official federal and state documents, mapping SE for adolescents and young people revealed that 76% of these documents did not use the term “SE” but mainly used the term “prevention”. The largest number of proposals with SE-related actions (56%) comes from the Ministry of Health and points to actions between the health sector and others, such as education, with emphasis on the Project “Health and Prevention at School” (Ministério da Saúde do Brasil, 2006, 2009). Thus, SE has mainly focused on the prevention of HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy in childhood and adolescence.

Therefore, after 20 years of implementing the PCNs, studies that use instruments to assess SE in terms of knowledge, attitude, and behavior may help educators and healthcare professionals better understand these issues, which they encounter on a daily basis. The present study distinguishes itself in the field of health by expanding the SE theme beyond merely biological and preventive aspects. It will be instrumental in generating attitudinal and behavioral data that can be associated with exclusively qualitative studies.

This study assesses the degree of knowledge, comfort, motivation, and involvement of elementary school teachers in the promotion of SE in school by considering their age, initial academic foundation in SE, and religious beliefs.

2. MAIN OBJECTIVE

To assess the degree of knowledge, comfort, motivation, and involvement of elementary school teachers in the promotion of SE in school.

3. METHODS

A convenience sample was employed in this cross-sectional study. Elementary school teachers from private, state, and municipal schools in São Paulo participated in the study with a traditional or constructivist pedagogical line. Answers from high school teachers were excluded. The sample size was adapted from Osborne and Costello (2004), considering the principal components analysis of instruments necessary for its validation (300 = good; Pássaro, 2019).

This study adhered to the National Council of Health/Ministry of Health’s Resolution no. 466/12 governing the ethics of human research. In the questionnaire instructions, all participants were informed of the research procedures and given the option to withdraw their consent to participate in the study at any time.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, Brazil (CAAE: 48385715.7.0000.0065 / Number of Opinion: 1.360.769).

All participants signed approved informed consent forms.

3.1. INSTRUMENT

The Questionnaire on Sex Education in Schools (QUSES) is a self-administered questionnaire on SE that evaluates the knowledge of current legislation, sociodemographic characteristics, initial/continuing training in this field, previous experience, and teachers’ intention to promote SE. In addition, it evaluates three psychological variables: (1) teachers’ comfort when addressing themes about sexuality; (2) teachers’ motivation through the degree of importance attributed by participants to SE-promoting activities, which can be measured by self-efficacy (a teacher’s ability to execute certain courses in SE) and result efficacy (the expectations that the teacher has in relation to the consequences of promoting SE); and (3) teachers’ behavioral and cognitive involvement in specific SE actions. It includes 27 questions to be answered in approximately 30 minutes. The questions are clear and easy to understand, and most answers are scored on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6 (Lemos et al., 2013; Pássaro, 2019; Pássaro et al., 2019; Serrão, 2009).

The questionnaire scores are based on the dimensions and not on the totality of the answers:

Knowledge (1-15 items): The possible answers include “true”, “false” and “do not know” (with the correct answers being counted, minimum knowledge = 1 and maximum knowledge = 15).

Comfort (30 items): This scale analyzes two dimensions: (1) body, including sexual and reproductive health; and (2) body, including sexual practices and behavior, with 1 being very uncomfortable (minimal) and 6 very comfortable (maximum).

Motivation: This scale integrates three subscales:

Involvement (29 items). This scale analyzes two dimensions: (1) pedagogical practice (1 = never; 2 = rarely; 3 = few times; 4 = sometimes; 5 = oftentimes; 6 = always), keeping the relations of minimum at 1 and maximum at 6; and (2) pedagogical function (1 = strongly agree; 2 = moderately agree; 3 = agree more than disagree; 4 = disagree more than agree; 5 = moderately disagree; 6 = strongly disagree), reversing the minimum and maximum ratio (maximum = 1 and minimum = 6), which implies that the lower the final result, the greater teachers’ understanding of their responsibility in promoting SE (Lemos et al., 2013; Pássaro, 2019; Pássaro et al., 2019; Serrão, 2009).

To use this instrument with teachers, a methodological study of cultural adaptation, reliability, and content validation was initially conducted (Pássaro et al., 2019). As part of the questionnaire validation phase, each dimension, with the exception of knowledge, was subjected to factor analysis using the principal component analysis (Pássaro, 2019).

3.2. PROCEDURE

The data were collected using Google forms from May 2016 to July 2017. Questions regarding the school where religious beliefs and sexual orientation are taught were added because they were not included in the original instrument.

With the digital instrument, it was decided to begin data collection through the municipal and state departments of education so that they could forward the e-mails with the questionnaire link to the teaching boards and coordinators.

3.3. DATA ANALYSIS

The data exported from the database in the Microsoft Excel program were transported and processed in the IBM SPSS version 15.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). To compare the means of the variables established in the specific objective, scatterplots were used to analyze different age groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey’s post hoc test to analyze religious beliefs, and Student’s t-test for independent samples considering the initial SE training of teachers.

The effect size (ES) was also used for sample analysis, which has been recommended in studies with psychological and educational variables, among others, to attribute importance and practical applicability to the results (Espírito-Santo & Daniel, 2015, 2017, 2018). The terminology used for the ES was Cohen’s adjusted measure, calculated on the website (https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html#cohenb). The ES will not be discussed quantitatively as small, moderate, and large because comparisons could not be made with similar data. However, intervention studies in education present an ES of approximately 0.30 (Espírito-Santo & Daniel, 2015); therefore, 0.20 was considered the baseline in this study. The ES related to the Afro-Brazilian group was not considered due to the small sample size (n = 6).

4. RESULTS

A total of 417 respondents participated in the data collection; however, 21 were excluded because they were high school teachers; thus, 396 participants were included. Table 1 outlines the sample’s sociodemographic variables.

Table 1: Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

| Variables | n = 396 (%) |

| Sex | |

| Female Male | 307 (77.53) 89 (22.47) |

| Age (standard deviation) | |

| Female Male | 43.63 (9.06) 42.97 (10.79) |

| Marital Situation | |

| Married | 222 (56.06) |

| Single | 88 (22.22) |

| Stable union | 43 (10.86) |

| Divorced | 38 (9.60) |

| Widow/er | 5 (1.26) |

| Number of children | |

| None | 140 (35.35) |

| One | 81 (20.45) |

| Two | 108 (27.27) |

| Three | 40 (10.10) |

| More than four | 25 (6.32) |

| Missing data | 2 (0.51) |

| Cities | |

| São Paulo | 212 (53.54) |

| Others | 144 (36.36) |

| Mogi da Cruzes | 15 (3.79) |

| Bauru | 13 (3.28) |

| Ribeirão Preto | 12 (3.03) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 369 (93.18) |

| Homosexual | 16 (4.04) |

| Bisexual | 11 (2.78) |

| Religious belief | |

| Catholic | 189 (47.73) |

| Protestant | 55 (13.89) |

| Spiritist | 51 (12.88) |

| Without religion | 49 (12.37) |

| Others | 46 (11.61) |

| Afro-Brazilian | 6 (1.51) |

Table 2 describes the formation and professional characteristics of the sample, with 70.71% of the teachers having no academic training in SE and 51.52% teaching in elementary school II 3 .

Table 2: Characteristics of Training and Professional Performance of Participants

| Variables | n = 396 (%) |

| Academic Formation in Sex Education | |

| No | 280 (70.71) |

| Yes | 116 (29.29) |

| Education Level | |

| Completed higher education | 185 (46.72) |

| Postgraduate Latu Sensu | 148 (37.37) |

| Complete master’s | 30 (7.58) |

| Incomplete master’s | 15 (3.79) |

| Incomplete higher education and doctorate | 10 (2.52) |

| Complete doctorate | 8 (2.02) |

| Formation | |

| More than one formation | 121 (30.56) |

| Pedagogy | 68 (17.17) |

| Letters | 50 (12.63) |

| Biology | 38 (9.60) |

| History | 35 (8.84) |

| Mathematics | 32 (8.08) |

| Physical Education | 21 (5.30) |

| Arts | 16 (4.04) |

| Geography | 14 (3.54) |

| Psychology | 1 (0.25) |

| Time teaching (years) | |

| 1-10 | 114 (28.78) |

| 11-20 | 153 (38.63) |

| More than 21 | 129 (32.58) |

| Teaching cycle | |

| Elementary Education I | 97 (24.49) |

| Elementary Education II | 204 (51.52) |

| Both | 60 (15.15) |

| Others (Elementary II and Secondary Education; direction and coordination) | 35 (8.84) |

| Discipline taught | |

| Humanities (arts, history, geography, and languages) | 137 (34.59) |

| Polyvalent | 89 (22.47) |

| Biological (physical education and science) | 79 (19.95) |

| Exact (mathematics) | 43 (10.86) |

| Others | 48 (12.12) |

With respect to continuing education in SE, 60.86% of the participants had no formal training in SE, and among those who had, 17.17% had never participated in colloquia or congresses on the theme, and 16.41% had participated in SE courses only once, whereas 12.12% had participated several times. Regarding SE at school, 12.12% never received it, and 11.62% had only received it once. In addition, 57.32% had never promoted or participated in SE-related activities throughout their teaching career. Among those who had participated in some activity, 21.21% had held an articulated set of classes for students, with the majority (30.05%) finding that the action was fully satisfactory and only 1.77% finding it unsatisfactory with many negative aspects.

Most teachers were active participants (22.98%) or had participated in the organization of SE-related events (19.70%). Regarding their performance in these SE-related events, the majority (28.28%) felt confident and prepared, whereas 19.70% enjoyed it but felt additional training was necessary.

Table 3 displays the result of the socio-cognitive variables that comprise QUSES (Questionnaire on Sex Education in Schools), with the respective minima and maxima of each scale/subscale and corresponding factors.

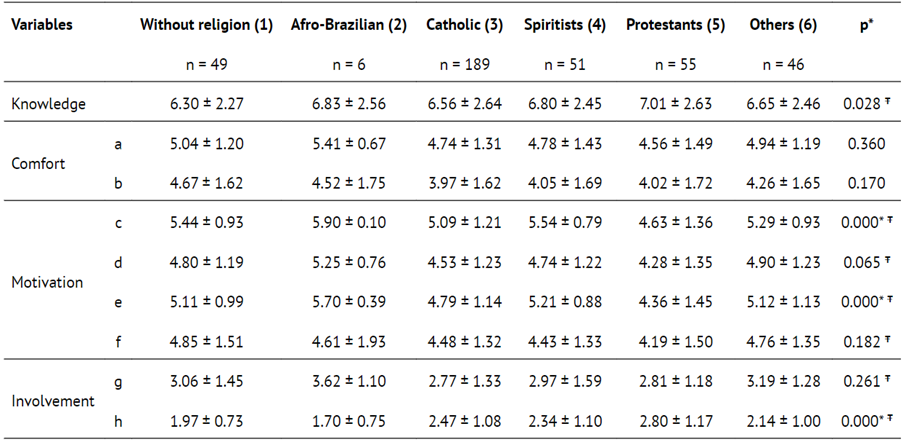

Regarding the teachers’ age, we found a weak correlation with all the QUSES variables. Table 4 shows the comparison of the means of the QUSES variables according to religious beliefs, which had an impact on the variables analyzed, with the exception of comfort.

Table 4: Comparison of the Means of the QUSES Variables According to Religious Beliefs

* One-way ANOVA (Tukey’s Post Hoc Test); Ŧ ES: Effect Size (d Cohen’s impact ≥ 0.20); a - Factor 1: Body: sexual and reproductive health; b - Factor 2: Body: sexual practices and behavior being; c - Subscale: Importance; d - Subscale: Self-efficacy; e - Subscale Result Efficacy: Positive beliefs; f -Subscale Result Efficacy: Negative/neutral beliefs; g - Factor 1: Pedagogical Practice; h - Factor 2: Pedagogical Function; Differences found in the respective analyzes: Knowledge (1-4) (1-5); Motivation c (5-1) (5-4) (5-6) e (3-4) (4-5) (5-6); Motivation d (3-6); Motivation e (5-1) (5-4) (5-6) e (3-4) (3-6) (4-5) (5-6); Motivation f: (3-6) (4-6) (5-6); Involvement g: (3-6); Involvement h: (5-1) (5-6) e (1-3) (1-4) (1-5) (3-5) (4-5) (5-6).

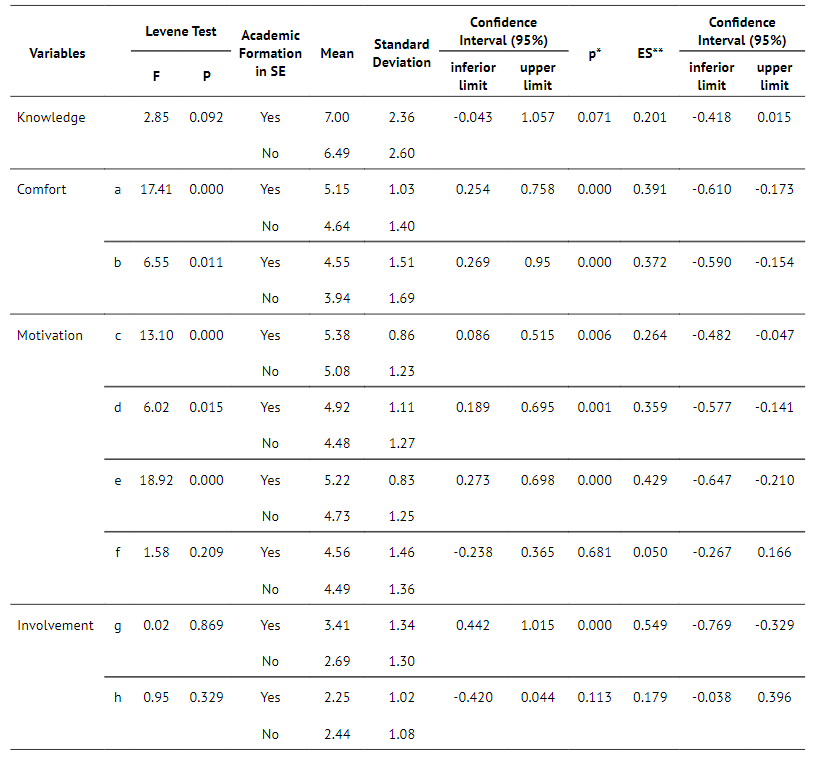

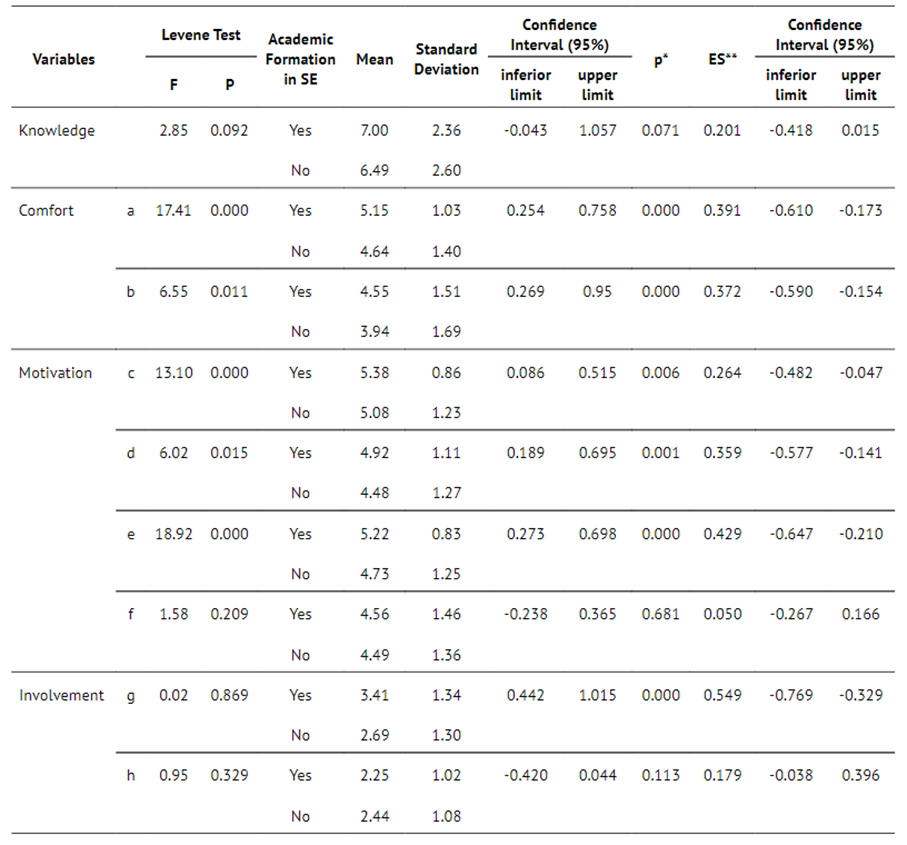

Table 5 exhibits the comparison between teachers according to their academic foundation in SE. No statistical difference was observed between knowledge, result efficacy (negative/neutral beliefs), and involvement in pedagogical function when considering teachers’ academic foundation in SE. For the other variables analyzed by QUSES (comfort, self-efficacy, result efficacy [positive beliefs], and involvement in pedagogical practice), this study found a statistically significant difference. However, having an academic foundation in SE did not significantly affect all the studied variables.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the degree of knowledge, comfort, motivation, and involvement of elementary school teachers in promoting SE in schools. Our results indicate that teachers showed moderate knowledge regarding legislation and ministerial guidelines on SE, high comfort, and motivation. Although their practical involvement in specific SE actions was insufficient, teachers agreed that it was their responsibility to be involved. Moreover, religious beliefs had an effect on QUSES variables. Our results are similar to Portugal’s data regarding knowledge, comfort, motivation (positive beliefs), and practical involvement in SE (Serrão, 2009).

The moderate knowledge related to the legislation and ministerial guidelines on SE is possibly associated with the number of existing laws and decrees for education and, more specifically, SE (Ministério da Educação do Brasil, 1990, 2013, 2015; Sfair et al., 2015). It may be important to discuss issues, such as the lack of knowledge about who authorizes SE and when SE should begin in the initial and ongoing training of teachers and healthcare professionals.

The two-dimensional comfort scale, which evaluates the biological and behavioral aspects of sexuality, managed to reflect what qualitative studies have been describing (Furlanetto et al., 2018). These studies indicate that interventions in Brazilian schools are medically informative and therefore focused on sexual and reproductive health (Furlanetto et al., 2018; Jaques et al., 2012; Soares & Monteiro, 2019). Generally, they concluded that teachers’ discomfort could be an impediment to SE practice in school as these interventions transpire in isolation (Ew et al., 2017; Furlanetto et al., 2018). However, our study corroborates the findings of Serrão (2009), Alvarez and Pinto (2012), and Lemos et al. (2013), who described teachers’ moderate comfort when dealing with the theme of sexuality. This scale was able to quantify the tendency of teachers to be less comfortable discussing aspects of the body (sexual practices and behavior), but teachers' discomfort cannot be confirmed (Furlanetto et al., 2018; Lemos et al., 2013; Serrão, 2009). However, aspects of SE, in addition to purely biological and reproductive concepts, should be considered in the initial and ongoing training of professionals working on this topic.

Regarding motivation (positive beliefs), our study and that of Serrão (2009) demonstrate that teachers’ belief that SE enables students to make decisions about their love and sex life, know how to choose their personal values, and avoid the risks associated with sexual activity, allowing for the development of sexuality-related personal skills and knowledge. Although this belief variable was not predictive of the practical involvement of SE in Serrão’s (2009) study, understanding beliefs and values is important as these can influence the practices of teachers and healthcare professionals (Beiras et al., 2005; Passmore, 1980). According to Foucault (2014), discursive practices that socially determine attitudes/objects that are right and wrong and normal or abnormal manifest themselves in the power-knowledge relationship that underlies the relationships established in society and is fed back by the active subjects in their relations.

The practical involvement in Brazil and Portugal is insufficient, which is in accordance with other studies (Alvarez & Pinto, 2012; Jaques et al., 2012; Serrão, 2009). Comparing teachers' practical involvement in light of the fact that Portugal has not yet determined the workload for SE would be interesting (Alvarez & Pinto, 2012). This came into existence in 2009 through Law No. 60/2009 of August 6, establishing the regime for the application of SE in schools (Alvarez & Pinto, 2012).

Although studies have identified that SE-related actions occur due to variables related to teachers and not to macrosystems (laws and regulations) and microsystems (school projects), it does not mean that actions in these instances should not be considered (Serrão, 2009; Soares & Monteiro, 2019). Serrão (2009) highlighted important strategies at the macro and micro levels, as the isolated effort of some individuals alone is not enough to change the practice related to SE actions. Cooperation between public sectors, specifically health and education, that can influence and encourage teachers and healthcare professionals to promote SE is therefore critical.

For the variables related to motivation (importance and self-efficacy), the values found in our study were higher than those in the study by Serrão (2009). In other words, Brazilian teachers consider themselves more prepared than Portuguese teachers, and it is crucial to provide guidance on SE. Importance and self-efficacy were higher for biological content, that is, pregnancy and contraceptive methods, in other studies, which can provide an understanding of the main objective of SE-related actions (Brandão & Lopes, 2018; Reis & Maia, 2012; Serrão, 2009; Yared & Melo, 2018). In addition, teachers considered themselves more capable of dealing with anxiety and fear, similar to the Portuguese study by Serrão (2009). Thus, our study differed from others that confirm teachers' insecurity when responding to sexuality-related questions (Ew et al., 2017; Figueiró, 2006; Varela et al., 2015).

The importance variables (negative/neutral beliefs and involvement in the pedagogical function) differ the most between the two countries. In Brazil, the high values for positive and negative/neutral beliefs seem contradictory; however, they can accurately demonstrate teachers’ conflicts of critical reflection on the theme (Passmore, 1980).

To support questions regarding a critical reflection on SE in the academic foundation of teachers and healthcare professionals, additional studies demonstrating clear and objective evidence for and against these established beliefs are warranted. Few studies have evaluated the outcomes of educational intervention in SE, which can contribute to the common knowledge favoring the strengthening of beliefs. These beliefs can hinder the development of critical thinking by professionals, which is an essential point for educators who are committed to teaching (Passmore, 1980).

Involvement in pedagogical function was the most notable difference between the two countries. In Brazil, it is moderately agreed that the role of the school goes beyond preparing students for employment (job market) and higher education, whereas in Portugal (Serrão, 2009) this issue is moderately disagreed upon. Therefore, the results pointed to the understanding of differences in the role of school education.

Our data show that teachers’ age and initial academic foundation do not affect the variables analyzed, which is in agreement with another study that did not verify the relationship between age and efficacy in SE (Alvarez & Pinto, 2012). Regarding initial training, a study by Alvarez and Pinto (2012) unveiled that only teachers who considered their training sufficient had a more comprehensive perspective on SE. Only a third of the participants had received initial training in SE, which corroborates our study’s findings.

The effect of religious beliefs on all variables of the questionnaire can be verified, with the exception of comfort. Although teachers were comfortable and committed to the theme of SE, religion interfered with the QUSES variables and was considered critical in terms of practical involvement in SE. This may be an important and relevant aspect of our study to be considered in teacher education programs related to the theme of SE at schools, especially in the context of growing political conservatism, as has been highlighted in the literature (Brandão & Lopes, 2018; Carvalho & Sívori, 2017; Rosado-Nunes, 2015). This finding differs from a study that did not find religious belief to have an influence (Alvarez & Pinto, 2012). Carvalho et al. (2017) found that young Portuguese children whose mother was a sex educator received more than five years of SE at school and had no religious involvement, indicating a correlation between the absence of belief and SE knowledge.

The Brazilian Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Associations (FEBRASGO) and the Brazilian Society for the Study of Sexuality (SBRASH) also recognize that SE should be addressed in elementary school and high school, which may reduce sexual violence and risky sexual behavior among teenagers. They suggest that a serious, ethical, and scientific evidence-based approach to the topic can help develop a sexually healthy society (Brazilian Committee Specialized in Sexology of FEBRASGO & Brazilian Association of Studies on Human Sexuality, 2018). Thus, this study contributes to the fields of education and healthcare, strengthening scientific knowledge, opening paths for new reflections on SE, and highlighting actions between sectors in the continuing training of professionals and in practical interventions in daily school activities and healthcare units.

6. CONCLUSION

Teachers presented moderate knowledge regarding legislation and ministerial guidelines regarding SE, high comfort, and motivation. Although they showed insufficient practical involvement in specific SE-related actions, they agreed that it was part of their responsibility to be involved. Finally, even though teachers’ age and initial academic background had no effect on such involvement, religious beliefs affected the QUSES variables.