Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), adolescence is the developmental period from childhood to adulthood.1 Globally, one in seven 10-19 year olds experience a mental disorder, accounting for 13% of the global burden of disease in this age group.2,3 Adolescence has the highest incidence of affective disorders, particularly depressive disorders, and suicide is a leading cause of death among 15-24 year olds worldwide.2,4,5

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) defines Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) as a syndrome that includes at least five symptoms (such as depressed mood and suicidal thoughts, among others).6 Therefore, MDD is associated with several symptoms and risks, including suicidality.4 According to the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases-11 (ICD-11), several manifestations of suicidality can be considered (Table 1).7

Table 1 ICD-11 definition of suicidal events7

| Event | Definition |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | Intentional self-injury inflicted to the body with the expectation that it will only lead to minor physical harm. |

| Suicidal ideation | Thoughts about the possibility of ending one’s life. |

| Suicidal behavior | Concrete actions taken in preparation for ending one’s life, without constituting suicidal attempt. |

| Suicidal attempt | Concrete behavior with the conscious goal of ending one’s life. |

The international guidelines suggest managing mild depression in adolescents with psychological therapies, while antidepressants are not recommended at this stage.8 Clinicians are instructed to manage moderate to severe depression with a combination of psychological therapy and an antidepressant.8,9 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the only antidepressants approved for pediatric patients and are the most commonly prescribed in the clinical practice.8-10

Although the adolescent serotonin system is thought to be similar to that of adults, some studies have shown several findings that suggest some differences, such as an important decrease in serotonin 1A (5-HT1A) binding and increased expression of the serotonin transporter in non-serotoninergic brain areas.4 Maturation of the noradrenaline system is also thought to be delayed.4

Although SSRIs are known to improve several depressive symptoms, their use in children and adolescents has been questioned due to safety concerns, namely suicidal ideation and behavior.10-13 Concerns peaked in 2004 when the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning after a meta-analysis of 372 clinical trials showed increased suicidal ideation and behavior in patients receiving antidepressant treatment.13 This led to a decrease in antidepressant prescriptions among adolescents and a paradoxical increase in suicide attempts.11,13 Several studies have since challenged this warning.4,11

The last report of the Portuguese authorities on suicide accounted for 9.5 per 100,000 people in the year 2019.14 Portugal has a high rate of antidepressant use compared to other European countries, with an increase of 83.5% between 2010 and 2020.15 As is the case worldwide, SSRIs − most commonly sertraline − are the most prescribed antidepressants in the country.16

The aim of this study was to understand the relationship between antidepressant use and suicidality in an adolescent population followed at an Adolescent Psychiatric Unit in Lisbon, Portugal.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This study was conducted in patients who were referred to a psychiatric consultation at the Adolescent Psychiatry Unit - Clínica da Juventude, Hospital Dona Estefânia. Only patients with a first appointment during the year 2021 were included. Exclusion criteria comprised (1) ongoing antidepressant treatment at the first appointment, (2) absence of depressive symptoms at referral and/or at the first clinical assessment; and (3) insufficient data. Depressive symptoms were identified according to the ICD-11 symptomatology described for depressive disorders: depressed mood, decreased interest in activities, feelings of worthlessness, excessive guilt, hopelessness, recurrent thoughts of death, and reduced energy.7

Study procedures

A controlled retrospective cohort study was conducted to examine how adolescents with depressive symptoms respond to SSRIs. All patients had an identification number that allowed for the collection of digital and physical records. Anonymity was maintained to ensure confidentiality. Data extraction was performed by child and adolescent psychiatry trainees.

Assessment

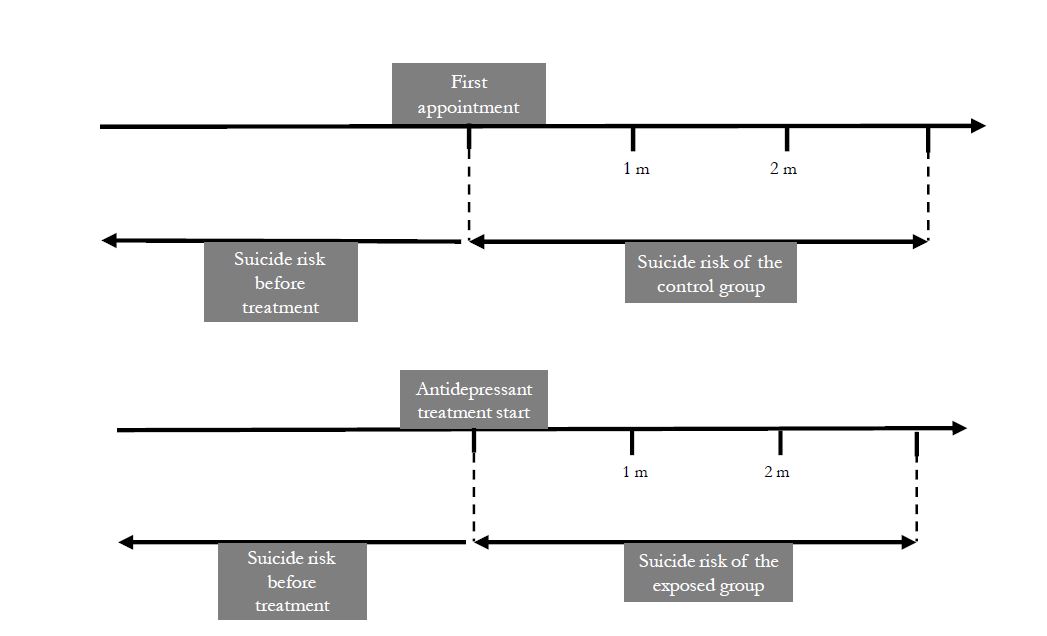

Data collected included sociodemographic information (age and gender), symptomatology prior to referral and initiation of antidepressant therapy (depressive symptoms, nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and suicide attempts), pharmacologic therapy (antidepressant and date of initiation, as well as antipsychotic and anxiolytic medications), and posterior suicide attempts within the next three months (Figure 1).

Descriptive statistics were initially used to describe participants’ age and gender, psychiatric background, treatment, and outcomes to compare samples and calculate relative risk. Two-tailed tests were used to determine statistical significance at the 5% level between variables and outcome, and Bayesian analysis of independent samples was used to obtain a measure of the strength of evidence. Pearson correlation r was calculated to measure the correlation between the two variables. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26, Armonk, New York).

Results

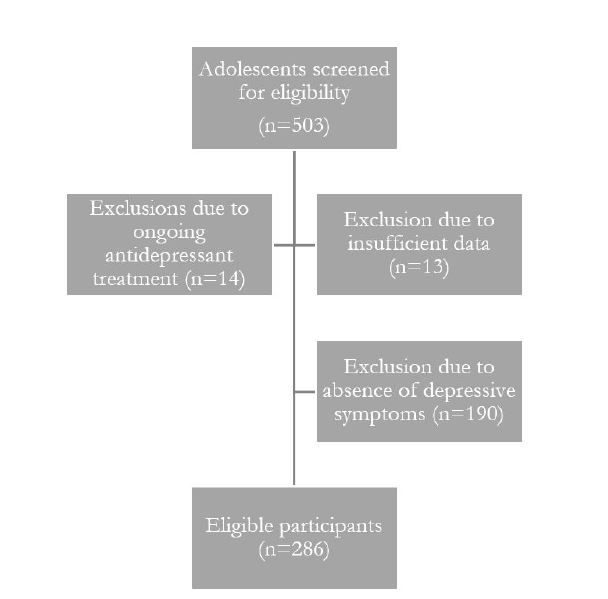

A total of 503 adolescents were initially enrolled, of whom 13 were excluded for insufficient data and 14 were excluded for already being on antidepressant treatment at the first appointment (Figure 2). After analysis of referral letters and first appointment notes, 190 patients were excluded for lack of depressive symptoms, leaving a final sample of 286 participants.

Of the 286 study participants, 213 were girls and 73 were boys. The mean age was 15.02 years. The exposed population consisted of 164 adolescents, and the control group consisted of 122 adolescents. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the study population.

Table 2 Characteristics of the study population

| Exposed group | Control group | Total population | |

| Population (N) | 164 | 122 | 286 |

| Gender (m:f ratio) | 30:130=0.23 | 43:80=0.54 | 73:213=0.34 |

| Mean age (years) | 15.12 | 14.89 | 15.02 |

| History of non-suicidal self-injury (N, %) | 79 (49%) | 73 (59%) | 152 (53%) |

| History of suicidal ideation (N, %) | 70 (43%) | 47 (38%) | 117 (41%) |

| History of suicidal behavior (N, %) | 23 (14%) | 14 (11%) | 37 (13%) |

| History of suicidal attempts (N, %) | 24 (15%) | 15 (12%) | 39 (14%) |

| Antipsychotic treatment (N, %) | 113 (69%) Quetiapine 50 (30%) Risperidone 34 (21%) Olanzapine 21 (13%) Aripiprazole 7 (4%) | 67 (54%) Quetiapine 28, (23%) Risperidone 23 (19%) Aripiprazole 6 (5%) Olanzapine 5 (4%) Paliperidone 4 (3%) Clozapine 1 (0%) | 180 (63%) |

| Anxiolytic treatment (N, %) | 62 (38%) Loflazepate 36 (22%) Alprazolam 14 (9%) Diazepam 7 (4%) Lorazepam 5 (3%) | 31 (25%) Loflazepate 26 (21%) Clonazepam 2 (2%) Diazepam 2 (2%) Alprazolam 1 (0%) | 93 (33%) |

| SSRI treatment (N, %) | 164 (100%) Sertraline 95, (58%) Escitalopram 40 (24%) Fluoxetine 29 (18%) | 0 | 164 (56%) |

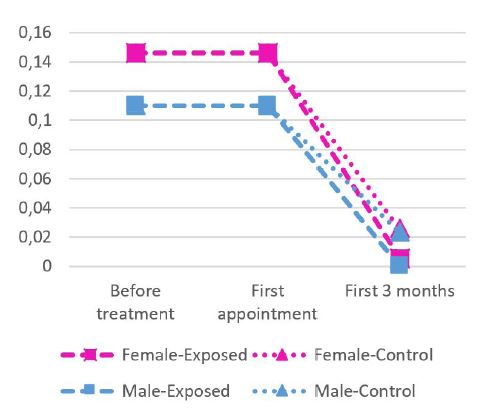

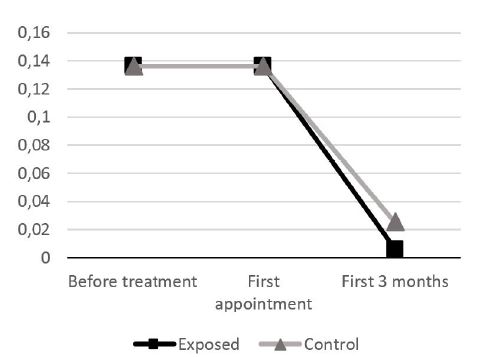

There were no cases of suicide in the study population. Conversely, four suicide attempts were reported during the three-month follow-up period. One suicide attempt was recorded in the antidepressant exposure group (1/164=0.006) and three in the control group (3/122=0.025). Figures 3 and 4 show the risk of suicide attempt among adolescents exposed and not exposed to antidepressants and according to gender. Overall, the relative risk of suicide attempt was 0.248. The Bayesian test for independent samples retrieved a Bayes factor of 4.57. The p-value for a 95% confidence interval for this risk was 0.189 and Pearson’s r was -0.078.

Figure 3 Risk of suicide attempt in adolescents exposed and not exposed to antidepressants during the study period

Discussion

The results of this study, including Pearson’s r close to 0, do not support an association between antidepressant treatment and suicide attempt. The higher incidence of suicide attempt in the control group was not statistically different from the incidence in the exposed group and could be due to chance. Bayesian analysis suggested moderate evidence for the study hypothesis.17 The results suggest that antidepressants might have a small protective effect against suicide attempt, but lack power to draw conclusions, even when female and male adolescents are analyzed independently. The group exposed to antidepressants had a higher male-to-female ratio, which may support the results, as female adolescents are thought to be more prone to suicide attempts.18 The size of the study sample did not allow conclusions to be drawn regarding the effect of age and concomitant antipsychotic and anxiolytic treatment on suicide risk. The results are in line with those of several recent studies suggesting that SSRIs do not increase the risk of suicidal behavior.10

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged: (1) despite similarities, the control group has several differences from the exposed group; (2) clinicians decide whether and how to initiate antidepressant treatment according to their clinical judgment; (3) antidepressant dosage and titration were not taken into account, nor were concomitant psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy and concomitant antipsychotic or anxiolytic medication; (4) suicide risk before exposure to antidepressant treatment was calculated within a longer time frame than suicide risk after exposure to antidepressant treatment; and (5) comorbidities were not considered.

Importantly, in addition to psychopharmacological treatment, patients and their families were regularly followed up with psychosocial support, which usually continued for more than three months until clinical discharge.

Although the lack of a difference in the suicide attempt rate between males and females is an important study finding, a larger sample would potentially allow for more significant results, and a randomized controlled trial might lead to stronger conclusions.

Conclusion

The study findings suggest that SSRIs do not increase the risk of suicide attempt among adolescents.

Authorship

Nuno Duarte - Conceptualization; Resources; Data curation; Formal Analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing

Sarah Amaral - Conceptualization; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing

Marta Abrantes - Conceptualization; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing