Introduction

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is defined as the occurrence of recurrent wheals, angioedema, or both that persist for more than six weeks without a triggering event. Symptoms can be disabling, significantly affecting sleep, productivity, and quality of life.1 Recent studies suggest that CSU affects 0.27−1.98% of children.2

Several guidelines have been published over the last years focusing on the optimal management of CSU in the adult population, but there is a paucity of recommendations for the pediatric population.1-3 Specific guidelines directed at children are scarce, primarily due to the lack of high-quality evidence for the use of several treatment options in this age group.1-3 The currently recommended therapeutic approach includes once daily second-generation antihistamines at standard doses as first-line therapy, which may be increased up to fourfold in second line to achieve clinical remission.4 However, in some cases, antihistamine therapy is insufficient and these patients require other treatment modalities.

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody approved as add-on therapy for patients with antihistamine-refractory CSU older than 12 years of age (third line). For children with antihistamine-refractory CSU younger than 12 years, the therapeutic options are limited, and systemic immunosuppressants with significant adverse effects, such as oral corticosteroids or cyclosporine, are often used.

Herein is reported a case of refractory CSU in a child who achieved symptomatic control with omalizumab.

Case report

An eight-year-old boy with a history of migratory maculopapular skin lesions with eight weeks of evolution was referred from the Emergency Department to the Pediatric Rheumatology consultation. The skin lesions were described as erythematous, non-ecchymotic, pruritic, some lasting more than 24 hours (figures 1-5). In addition to the skin lesions, the patient had arthralgias of the shoulders, wrists, knees, and tibiotarsal joints and conjunctival hyperemia.

After Rheumatology consultation, the boy was started on oral betamethasone (0.03 mg/kg/day) and bilastine (10 mg twice daily) for four weeks, with clinical resolution of the arthralgias and conjunctival hyperemia, but no improvement in the skin lesions.

The diagnostic hypothesis of urticarial vasculitis was considered and a multidisciplinary approach with Allergy and Clinical Immunology was undertaken. The analytical study - including complete blood count, general biochemistry, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thyroid function, antinuclear antibodies, complement fractions, serum immunofixation, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr serologies - was unremarkable. Total serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) level was 151 IU/mL. To perform a skin biopsy, betamethasone was discontinued and the antihistamine dose was increased to four times the standard dose. Skin biopsy was performed in the absence of corticosteroid therapy for one week, and histopathologic findings were consistent with urticaria, excluding vasculitis. Systemic corticosteroid therapy was restarted for uncontrolled chronic urticaria (Urticaria Activity Score Over 7 Days (UAS7) >31 points and Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (C-DLQI) 29 points).

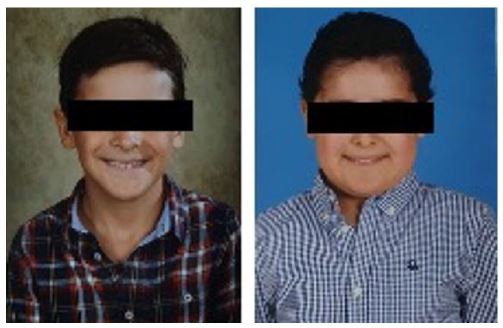

After five months of illness and several unsuccessful attempts to discontinue corticosteroid therapy due to recurrence of skin lesions with betamethasone tapering (<0.02 mg/kg/day), the patient developed several side effects (figure 6), including 11% body weight gain, hirsutism, cushingoid facies, and asthenia. He was started on cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/day while maintaining a fourfold dose of bilastine and gradually tapering the corticosteroids. After four weeks of treatment, no clinical response was observed (UAS7 35-40 points) and the C-DLQI was 29 points.

In addition to uncontrolled skin lesions, the boy began to complain of school bullying and manifesting depressive symptoms. Given the persistent skin lesions refractory to immunosuppressive therapy and their impact on the child’s quality of life, the medical team suggested adding omalizumab (300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks). Skin lesions improved after the first administration, and corticosteroid therapy was discontinued after one month of treatment. After the third administration, the child had achieved complete clinical resolution (UAS7 of 0 and C-DLQI of 0). After eight months of successful therapy, administrations were programmed to every six weeks, and after eleven months of therapy, to every eight weeks. On clinical reassessment after 15 months of treatment, the child reported numbness in the left leg and knee and foot pain. New blood tests were performed, including complete blood count, liver and kidney function, electrolytes, creatine kinase, myoglobin, vitamin B12, folate, vitamin D, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thyroid function, antinuclear antibodies (anti-dsDNA and anti-ENA), and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (anti-MPO and anti-PR3), with no abnormal findings. The patient was re-evaluated in Rheumatology consultation, with no abnormal findings on physical examination, and arthritis was ruled out. Considering these complaints as adverse effects, the dose of omalizumab was reduced to 150 mg every eight weeks. On re-evaluation after dose reduction, the child denied numbness or joint pain. Currently, after 22 months of treatment with omalizumab, he remains in clinical remission, with good tolerability and no adverse effects.

Discussion/conclusion

This study described the case of a male child with antihistamine-refractory CSU who was successfully treated with off-label omalizumab. Omalizumab is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of CSU only in patients 12 years of age and older. It has been safely used and is also approved by the EMA in children six to 11 years with severe asthma.5

There is limited published evidence on pediatric patients with CSU. Only a small number of pediatric patients with chronic urticaria have been enrolled in randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of omalizumab, and most treatment recommendations have been extrapolated from adult data.6-7

In the present case, the therapeutic decision to start omalizumab was based on the lack of response to antihistamines at the maximum recommended dose in combination with oral corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The patient developed side effects from corticosteroids, namely weight gain, hirsutism, cushingoid facies, and asthenia. Although he experienced no adverse effects with cyclosporine - such as nephrotoxicity or hepatotoxicity, gum hypertrophy, tremors, or elevated blood pressure - the use of this therapy in a child during the COVID-19 pandemic carried other risks, such as systemic immunosuppression.8

Regarding safety, the use of omalizumab in children with chronic urticaria under the age of 12 appears to be as safe as in asthmatic children over the age of six.9

To the authors’ knowledge, only a few clinical cases of off-label use of omalizumab have been reported to date.10-12 Most described successful treatment with this agent, with only two cases showing incomplete remission. Regarding adverse effects, one study reported minor adverse events (joint pain and injection-site reaction) in two patients.12

The adverse events reported in the present study had been previously described with omalizumab. Arthralgia was reported by the EMA in the Summary of Product Characteristics as a common adverse event of CSU treatment at the 300 mg dose.13 Paresthesia had also been described as a rare adverse event of omalizumab in studies of asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, but not urticaria. 13

Adult guidelines were extrapolated to the pediatric patient in this study and omalizumab was found to be safe and effective. Despite the adverse effects reported at the 300 mg dose, they were no longer reported with dose reduction and the patient remained asymptomatic.

In conclusion, omalizumab may be an effective and safe treatment for antihistamine-refractory CSU in children. It allowed the suspension of immunosuppressive therapy with regression of associated adverse effects and had a major impact on the child’s quality of life, particularly in terms of school and social performance. Further studies on the use of omalizumab in children under 12 years of age are needed, in particular to determine the minimum effective dose required to achieve disease control and the duration of treatment.

Authorship

Tânia Gonçalves - Conceptualization; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing; Validation

Iolanda Alen Coutinho - Conceptualization; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing; Validation

Joana Sofia Pita - Supervision; Writing - review & editing; Validation

Paula Leiria Pinto - Supervision; Writing - review & editing; Validation