Introduction

On Thursday, February 18th, 2019, The Standard, a Kenyan daily newspaper, ran a story on its front page reading: “Thousands of students taking ‘useless’ varsity degree courses”. I could not miss the story because it was accompanied by my photo. The story went on to state that, “thousands of students are wasting time and money studying useless degree programs in various Kenyan universities. The Commission for University Education (CUE) has rejected 133 courses with a cumulative enrollment capacity of 10,000 slots”.1 By “rejection” the newspaper story was alluding to the process of evaluating and accrediting university programs for offer by the requisite universities. No program is offered in a university in Kenya without the formal approval of the CUE, the government agency charged with overseeing quality university education in Kenya.

While the headline may appear shocking, the narrative of “useless degrees” is not an isolated phenomenon. It’s part of an orchestrated campaign to undermine and question the relevance of university education in Kenya, as part of a global neoliberal agenda that started in the 1980’s with Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) championed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (Emeagwali 2011; Ikiara 1991; Mamdani 2019; Unterhalter and Allais 2022). Another daily newspaper, The Business Daily, wrote the following day (February 19th, 2019): “Besides content of the courses, the CUE should broaden its mandate to include the marketability of the degree courses before giving a blanket approval”.2 In an increasingly changing world where some jobs that exist today may not be there in a decade or less, it is not feasible to determine which degrees are marketable. Given that Kenya does not have a reliable statistical projection of the jobs that will be available in the market in the future, how does one establish what degrees will be marketable upon graduation? The language of “useless” degrees and “marketability” of courses, while referencing Kenya, is a global phenomenon that shows up across many locations (see Atalay 2017; Carrigan and Bardini 2021; Darder 2019; Giroux 2018; Hlatshwayo 2022; Shore 2010; and Vicars and Pelosi 2023, among others).

There has always been great interest in university education in Kenya but the last two decades have seen increased interest in the value of a university education, which degree programs one ought to select, and ultimately the employability of university graduates.3 In the last few years of the 2000’s the conversation has been about science and technology programs but without a corresponding job market. Between 2018 and 2022, for instance, Kenyan universities graduated 5352 medical doctors, dentists and pharmacists and only 1000 of them were employed as of February 2023.4

Internally, Kenya’s Ministry of Education’s Sessional Paper, no. 1 of 2019, states clearly the value of university education in broader terms without emphasizing any specific programs. It states:

“University education is critical in producing a pool of highly skilled manpower in various specialized skills necessary for promoting higher productivity for national socio-economic development and carrying out research to provide solutions to societal challenges.” (Government of Kenya 2019: 32)

That university education plays an important role in building capacity for the technical and social advancement of nations is a reality noted by the government of Kenya and scholars (see Brown and Heaney 1997, and Odhiambo 2018). In 2008 the government initiated a blueprint for development titled Vision 2030 that was to be implemented over a period of 22 years.5 Upon its implementation Kenya would become an industrializing middle-income country with a high quality life for all its citizens (Kithinji 2011; Mugalavai 2012; Omamo, Rodrigues and Muliaro 2019). Divided into social, economic, and political pillars, Vision 2030 aims at providing globally competitive, quality education and research to build an industrializing economy. The heart of this transformation is a relevant, efficient, accessible and equitable university education system that is able to generate knowledge to respond to the current and emerging needs of society both locally and globally. Such a nimble system cannot be sustained by a narrow focus on marketable graduates based on the prevailing context of work where there is limited grasp of the jobs of the future.

Kenya, like all other nations of the world, is part of a web of interconnections brought by global processes where, as Hlatshwayo (2022) notes, universities are no longer seen as places providing critical citizenship but are there to help transnational businesses and corporations succeed in the global economy. For years the Kenyan education system has been modelled after that of Britain and the first public university, the University of Nairobi (which at its inception was named the Royal College Nairobi), tasked with awarding degrees through the University of London which determined its curriculum. This colonially-directed development of the university is prevalent across Africa (Nyamnjoh 2019), but there was an attempt in Kenya to challenge it. In 1968 a group of academics challenged the structure and content of the department of literature at the University of Nairobi. In a memo titled “On the Abolition of the English Department”, written in October 1968 and signed by three academics including Ngugi wa Thiong’o, there was a clear attempt to develop academic content suitable to the local realities, but this process was limited to a few entities in the university (Sicherman 1998).

Decolonizing the curriculum that the University of Nairobi academics were undertaking was part of activities geared towards providing an African-centered approach to university education by a crop of scholars that came out of universities in East Africa, who went on to be players in the critique of western educational paradigms. These scholars include the late Ali Mazrui, Mahmood Mamdani, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and Dani Wadada Nabuder e (Mamdani 2016; Mazrui 1974; Nabudere 2006; and wa Thiong’o 1986). University education allowed students and their professors opportunities to engage deeply in discussions of matters pertaining to the academic disciplines themselves as well as political matters affecting their own nations and Africa in general. Decolonizing the African university was a tall order. As Mamdani notes, “the modern university in Africa has very little to do with what existed on this continent before colonialism, and everything to do with what was created in modern Europe” (2019: 51). In the 1980’s the World Bank advocated for limited investment in university education arguing it had little, if any, “return on investment”. This economic measure of universities’ viability not only became the biggest threat to university education in the country but also laid down the foundation for the neoliberal agenda being experienced today (Unterhalter and Allais 2022).

The World Bank’s role in steering higher education in Africa towards the neoliberal frame intensified between 1986 and 1991 through its overt promotion of “a drastic reduction of higher education in Africa in the name of higher efficiency and a more egalitarian distribution of educational resources” (Caffentzis 2000: 3). Buoyed by a philosophy that measured the value of education by its “return on investment”, the Bank preferred an investment in higher education that had tangible immediate economic returns. As a result, many programs that had been set up to support university education in Africa were discouraged. These decisions by the World Bank were devastating coming on the heels of the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) of the 1980’s. SAPs were meant to bring about fiscal discipline and efficiency in running public entities in order to reduce debt and poverty (Emeagwali 2011). Part of the adjustment was to diminish and at times completely eliminate the role of the state in the provision of services, especially social services (Ikiara 1991). The World Bank later reconsidered its position on university education by seeing it as a key contributor to a country’s economic productivity (Bloom, Canning and Chan 2006), but the damage had been done with the new push for relevance. This paper explores these challenges facing university education in Kenya within the context of a neoliberal agenda that also involves quality assurance as a global practice and as a tool for grounded practices.

Quality assurance in a neoliberal era

The story of CUE rejecting 133 courses was part of this historical practice of neoliberal approaches to education that found new champions three decades after the failure of SAPs. The courses that were “rejected” had nothing to do with relevance or marketability but rather didn’t meet the agreed upon standard and regulations for offering courses. Some lacked proof of university senate endorsement, while others had not been submitted to the CUE for approval. However, the story was presented as one of “useless courses” to align with the prevailing neoliberal narrative on university education. Such a narrative presents university education as a commodity in the open market in which only certain programs need to be taught to meet the assumed goals of national development (Hlatshwayo 2022; Mamdani 2019). The preferred programs are those in the Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) category as parents, government officials, politicians, and employers demand “useful” and “relevant” degrees that produce “employable” graduates. The narrative was given credence at the highest level of government.

On Thursday, October 25, 2018, then deputy president of Kenya William Ruto weighed in on the neoliberal thinking about university education when he was reported in the Daily Nation newspaper as having said that “there are over 1000 students learning sociology and anthropology, but if you look at the requirements of the industry, how many anthropologists or sociologists do we need?” 6 What the deputy president (and president since 2022) was saying is that the country does not need the over 1000 students majoring in sociology and anthropology because they are not getting jobs. As a professional anthropologist this indictment of the discipline was particularly disturbing seeing as the deputy president was completing his doctorate in biological sciences and his full-time job was politics and leadership. Further I had a center stage view of the issues facing university education given my position as the chief executive of the national quality assurance body.

Leading a national quality assurance agenda in an educational context where the political class seeks to diminish the value of a broadly or liberally educated graduate creates all manner of complications. First, it becomes confusing to oversee a university sector in which on the one hand the constitution provides for the freedom to develop and teach all courses and programs while on the other national leaders and the media continue to undermine that freedom. Second, to equate the value of university degrees with the speed at which their graduates get employed is to clearly undermine and/or completely ignore the role of universities generally. Thus, there is confusion regarding universities’ primary role - should they offer education or training? As Assié-Lumumba (2006: 9) has noted:

“Conceptually, training connotes the acquisition of technical skills geared toward performing specific tasks without necessarily an opportunity or requirement for the learner to acquire competence in critical thinking, broader knowledge and character to understanding the wider educational and societal contexts.”

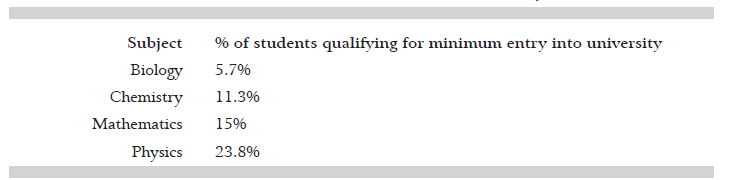

In a dynamic and changing world of work and social realities, focusing entirely on skill training as the neoliberal approach to education highlighted in the above cases, will result in a working population that cannot change with the times. Further, even the same employment sector being presented as in no need for social science and humanities graduates is responding differently. The June 2021 World Bank report on employment in Kenya, for instance, shows that the service industry accounted for over half of the nation’s employment and that there is increased earnings and labor participation among the better educated (World Bank 2021). There cannot only be one type of a graduate. Every economy needs both science and technology and social science graduates otherwise there will be no graduates with such competences as critical thinking, broad knowledge, thinking outside the box, and character building that provide foundational qualities of a society. It is quite telling that the meeting at which the Deputy President questioned the need for anthropology and sociology degrees was planned to promote technical training institutions, and yet enrolment in the preferred technical programs in Kenya is low. The low enrolment status is not because of the social sciences but partially as a result of hiccups in the educational pipeline where eligibility for certain technical programs in the university is dependent on students’ performance in foundational subjects in high school. An analysis of national examination results for students in high school for the year 2018, for instance, shows that fewer students qualified to be placed in technical courses in the university, especially biology. Further, poor performance in mathematics and physics may negatively affect enrollment in technology and engineering courses. Out of 654,630 students who sat for the national high school examination in 2018, for instance, only 171,847 sat for physics, 98,219 for mathematics, and 33,126 for biology. Students who qualified for admission to university with a grade of C+ or more in those subjects in 2018 were very few as shown in the table 1:

Table 1 % of students qualified to join university based on performance in select subjects in the national examination at Form Four level in 2018 in Kenya.7

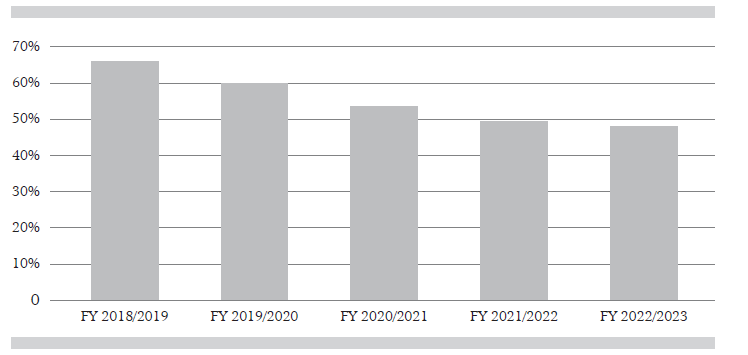

Besides low enrolment and performance in national examinations, STEM programs are very expensive to start and maintain. Many institutions, especially those with limited resources, cannot afford to mount and maintain STEM programs. Putting up laboratories and workshops and equipping them with requisite tools for use by students and lecturers is expensive. Many universities cannot afford them and often steer away from STEM programs. With public university funding increasingly reducing over the years it is unlikely that institutions in Kenya can adequately support STEM programs. The government of Kenya is mandated to provide funding support for universities at 80% of the cost of each unit offered but this target has not been achieved for a while. Figure 1 shows that the highest funding was provided in the 2018/2019 academic year at 64.4% which was 15.56% short of the target. In the 2022/2023 academic year the support had dropped to 48.11%.

Source: Universities funding board (www.universitiesfund.co.ke), accessed January 24, 2024.

Figure 1 Universities annual allocations

As a quality assurance agency charged with the mandate of overseeing quality in all universities in Kenya the CUE is caught up in this neoliberal expectation on university education and the struggles universities are enduring. To undertake quality assurance, the CUE periodically requires universities to provide evidence of academic resources needed to support all the academic programs on offer. It also ensures that the programs are mounted in accordance with statutory and legal provisions governing university education. Every year (around November) the Kenya Universities and Colleges Central Placement Service (KUCCPS) - an organization mandated to place students supported by the Kenyan government in universities and two-year colleges - sends out a request to CUE to validate placement spaces declared by all universities. Each university sends information to KUCCPS articulating the courses it will offer in the coming academic year as well as the slots available in which students can be placed. Those placement spaces entail the number of students each university can accommodate based on availability of supportive learning resources such as faculty, classroom and laboratory space, library material, etc. Given that the CUE regulates university education and regularly inspects the institutions for compliance to agreed upon standards and regulations, it is only fitting that KUCCPS consults the CUE for validation of declared placement spaces in universities.

In August of 2018 the CUE requested universities to declare all the learning facilities they had in place as well as the programs they were offering. Using the information that the universities shared in response to this request the CUE was able to advice KUCCPS on the available places for students based on availability of declared learning resources. In the process of reviewing the placement spaces declared by universities, the CUE established that the capacities declared could not all be corroborated due to the following: some of the facilities declared did not match the minimum number required for quality learning; there was no documented approval for programs being mounted in some constitute colleges; some institutions declared spaces in programs that had not yet been accredited by the CUE; and universities declared more options by splitting already approved programs into subsets that were then declared as stand-alone degree programs. While the CUE made a recommendation to KUCCPS not to place students in those programs based on the reasons given above, the media construed that the recommendation was due to the programs being useless and irrelevant.

University education: a basic right or a commodity?

Pushing for “relevance” and “marketability” moves university education from being a basic right to a commodity and yet the Constitution of Kenya, 2010 Article 43.1.f, guides that “every person has the right to education.” 8 That is why in January 2011, the then minister for education appointed a task force on the re-alignment of the education sector to the Constitution of Kenya 2010 to realign the education sector with the new Constitution and the country’s Vision 2030. The task force’s report addressed key matters in the following broad areas: relevance of education in content and delivery, flexibility to adapt to changing socio-economic needs, quality that matches global competitiveness for 21stcentury realities, effective governance and management, retention and transition rates for students, standards and quality assurance as well as monitoring and evaluation, access, and flexible and responsive regulatory framework that can deal with current and emerging challenges in order to ensure access equity and quality (Ministry of Education 2012: xxiii). The CUE was formed as part of these suggested reforms to streamline university education through close monitoring of quality, access, and relevance in service to the needs of the nation and its society. As envisaged in the Social Pillar of Kenya’s Vision 2030, programs in humanities and social sciences, creative arts, religion, sports science, architecture, etc. were to be part of university courses and programs.

In 2014, the CUE came up with a set of regulations that operationalized the Universities Act 2012. The regulations provided clear guidelines on how to establish a university, collaborate with external and internal institutions, and provide quality assurance mechanisms, among other functions. These regulations ensure that there are uniform expectations for all universities to follow. Yet such uniformity can, when used inflexibly, stifle creativity and turn the regulator’s work to an exercise of just checking boxes for a “one-size-fits-all” model of quality assurance. Such a model interestingly aligns with the neoliberal agenda for university education where institutions are not accorded any independence or creativity. As a result, universities are unable to fully exercise the constitutional provision for academic freedom.

It is difficult for universities to fully cultivate such academic freedom when bombarded with emphasis on market-based solutions even for social problems. Measures of social success based on “deliverables,” “bottom line,” “value for money,” “return on investment”, etc., become a moving target as the state is turned into a promoter of the free market instead of a provider of social services, and consequently negatively affecting university education. In such an approach universities become business entities that are left to compete with each other for “customers” by offering programs that the customers want (Atalay 2017; Carrigan and Bardini 2021; Darder 2019; Giroux 2018; Hlatshwayo 2022; Shore 2010; and Vicars and Pelosi 2023). Those programs are mostly ones that will make the clients “job-ready” and guarantee that they find employment upon graduation. This is not a phenomenon limited to Kenya but is replicated across the globe.9 Universities are expected to produce job-ready graduates by focusing on skills training preferably in Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields.10 Educational outcomes cannot be effectively equated to a commodity, nor can they be measured in the short-term period that is envisaged in the metrics and outcomes model of neoliberal capitalism.

Is the focus on relevant and marketable degrees a license to favor STEM courses at the expense of the social sciences and the humanities? A survey carried out by Kenya’s largest daily newspaper, the Daily Nation, highlights some of the skills employers look for in graduates and none particularly mention technical skills. Instead, they focus on “ability to learn and adapt fast”, “relentlessness and agility”, and “planning, strategy execution, people skills”.11 None of these skills are specific to STEM courses. Students do need to have specific skills that are inculcated in their disciplines, but the most critical skills for success in today’s world of work go beyond the technical ones taught in the disciplines. Students need transferable skills that are best taught in the liberal arts, the same fields that are now being seen as unimportant for success in today’s world.

The neoliberal approach to education can be linked to the growth of a capitalist ethic that seeks to erase the welfare state and turn the university into an institution whose education is a commodity. This new way of regarding and defining the university has consequences to how academics and students relate to each other. As Johan Nordensvärd (2011) notes, within a neoliberal context students become customers with preferences, not citizens with a right to education. How can one quantify in market terms the value of critical thinking, writing, and analytical skills that universities ought to teach their students? How can these attributes be measured in quantified metrics that are preferred by the market categories that define education in the neoliberal era?

The earlier emphasis on universities as places where thinking and exploration are encouraged has been replaced by performativity and accountability. Every state agency in Kenya goes through an annual exercise of signing a Performance Contract (PC) with the government providing clearly marked activities and stated measurable outputs. The PC has key criteria that each agency, including universities, need to follow to show effectiveness and productivity in such areas as financial stewardship and discipline, service delivery, core mandate, implementation of presidential mandate, and access to government procurement opportunities, among others. In 2003 the Kenya Government embarked on an economic recovery plan through which to make the public service more efficient and productive. The government’s Economic Recovery and Wealth Creation paper notes (Government of Kenya 2003):

“The Kenyan economy has performed poorly over the last two decades leading to deterioration in the quality of life of Kenyans. Among the reasons for this poor performance include poor implementation of economic policies and mismanagement, and weak institutions of governance.”

I have participated in the Performance Contract exercises on behalf of the CUE and one of the key things mentioned is that whatever is measured is what gets done. Because institutions and corporations are keen to be successful in this exercise, they may be tempted to have low achievable targets. Further when the real work of offering services, often embedded in individual sacrifices, gets done it is not easily measurable and can be sidelined. This is the context of metrics and measurements that informs the outcomes expected of university education in Kenya today.

Conclusions

Working in a context of neoliberal capitalism with measurements of success built around market attributes affects that very productivity by defining it in terms of measurable outputs. Granted there are indicators of how one attains set goals, many other contributing factors make to a system and a culture that are not immediately measurable. We cannot ignore those intangibles or delayed results in order to focus on the measurables that are mostly geared towards the short term. We cannot ignore the factors like time management that negatively affect such productivity. University education that is based on a neoliberal agenda of accountability and efficiency, accreditation and universalization, international competitiveness and massification, and privatization (Collins and Rhoads 2008), cannot assure students as well as faculty of an environment for deep academic thinking, research, and application of ideas. Instead students and faculty will continually be expected to fill out forms and measure specific output based on metrics developed elsewhere. Is this the end of university education as an intellectual engagement devoid of any constraints and full of flexibility and accommodating of all perspectives? Are we now in an era of education as a commodity and students as customers who know what they want to purchase? Only time will tell.