Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has had unprecedented global implications that go beyond health concerns and have profound consequences for world politics, the economy, and the social lives of individuals. With a seemingly non-discriminatory spread, the immediate and long-term impacts of this pandemic are likely to affect men and women very differently (Alon et al. 2020; OECD 2020). Existing discrepancies between men and women in caregiving and household work, as well as other pre-existing gender inequalities, such as gender-based violence and economic inequality, could be exacerbated by the unexpected onset of the pandemic (Alon et al. 2020; Correia 2020; Rosenfeld et al. 2020; World Economic Forum 2021).

In this article, we present an analysis of the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the dynamics of gender roles within mixed-gender couples. Specifically, we analysed how the first lockdown in Portugal affected the division of household and caregiving tasks between Portuguese men and women who were living together as a couple during this period. Using qualitative and quantitative approaches, we aimed at gaining insight into women's perceptions of their satisfaction with the division of household and care responsibilities within the couple, and the difficulties they faced in managing their workload during this period.

1. Pre-pandemic division of paid and unpaid workload among mixed-gender couples

In recent decades, there have been gradual developments toward greater gender equality in the labour force (Santos & Amâncio 2014; Casaca & Lortie 2017). The inclusion of women in the labour market, better educational opportunities, and the implementation of egalitarian laws have led to women’s increasing independence and economic empowerment (Lyonette, Crompton, & Wall 2007; Wall et al. 2017). According to the Eurostat database (Eurostat 2020), the employment rate of Portuguese women aged 15-65 was 66.9% in 2018, only slightly higher than the average of 63.3% for the 28 European Union Member States. However, the introduction of the dual-earner model in Portugal, as in most Western countries, has led to a disproportionate increase in women's total working hours. The increase in women's paid workload has not been accompanied to the same extent by a significant change in structural family dynamics. Also, there is an increasing pressure from the labour market on both male and female workers, since dominant socio-economic structures continue to conform to the representation of the worker as exempt from family responsibilities, highly available in terms of employment and working time flexibility (Casaca 2013). These processes exacerbate social and gender inequalities and entail important social costs.

Most women continue to bear the bulk of domestic responsibilities and the burden of balancing work and childcare. According to the European Institute for Gender Equality's Gender Equality Index Report (EIGE 2019a), about 38% of European women spend an hour or more per day caring for children, the elderly, and people with disabilities, compared with less than 25% of men who spend the same amount of time on these activities. For housework tasks (e.g., cooking and cleaning), the imbalance widens, with an average of 34% of men spending an hour or more every day on these activities, compared with 79% of women (EIGE 2019a). These asymmetries are also found to a greater extent in Portugal. On average, 37% of women spend at least one hour per day caring for family members, compared with 28% of men. For couples with children, this proportion increases to 87% of women and 79% of men. The gap also widens for household tasks, with 78% of women devoting at least one hour per day to these activities while only 19% of men do so (EIGE 2019b). Perista et al. (2016) also concluded that the sharing of household chores and care work within families in Portugal remains largely asymmetrical from a gender perspective, with women spending on average 4 hours and 23 minutes on unpaid work on weekdays, 1 hour and 45 minutes/day more than men. This trend is reinforced on weekends, when the authors estimate that women spend 12 hours (half a day) more than men doing unpaid work.

While data on time spent on paid and unpaid work reported by men and women provide a relatively objective view of inequalities, analysing satisfaction in the division of unpaid work offers valuable insights into subjective gender role norms based on individuals' cultural and ideological values that enable the perpetuation of this issue (Amâncio & Correia 2019; Cunha & Atalaia 2019; Ramos, Rodrigues, & Correia 2019). In an analysis of the 2002 and 2014 International Social Survey Program (ISSP) of housework sharing arrangements between Portuguese men and women, Amâncio and Correia (2019) showed that, despite the perception among women that they do more work than would be fair, and of men that they do less, there were significant changes in indicating a recognition of a more egalitarian division of housework.

Although promising, these numbers may not indicate a real change. According to recent research, small contributions by men in domestic and caregiving tasks are often perceived as sufficient to achieve equity (Wall et al. 2017). This “good enough” assumption can be counterproductive and can be seen as a modern take on the traditional gender roles, and further contributes to the persistence of gender asymmetries in domestic work. Also, women with higher education are less likely to perceive the division of housework as inequitable, which relates to their probable higher income, which frequently allows them to outsource housework and childcare, postponing the need to negotiate the division of these tasks within the couple (Amâncio & Correia 2019).

2. The impact of Covid-19 on gender dynamics within the couple: Effects of lockdown and widespread telecommuting

Recent research on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic suggests that conformity to traditional gender roles and gender stereotypes is likely to be endorsed by women and men during this period (Rosenfeld & Tomiyama 2020). The pressure of having to provide additional care for children at home may return to women's responsibility, conforming to traditional female roles.

To maintain physical distance, many workplaces were forced to switch to telecommuting. This new reality, which affected a large portion of the workforce, had the potential to disrupt family dynamics. Under normal circumstances, working from home can eliminate commuting time, increase free time for leisure, family, and community activities, and thus reduce stress levels (Casaca 2002). In a recent study, in Portugal, 54% of women responded positively to working from home during the initial closure period in March 2020, compared with 62% of men (Silva et al. 2020). Positive responses tended to increase during the lockdown, especially among women. However, previous research has also shown that the greater flexibility that telecommuting offers in terms of time allocation, disrupts work and family boundaries, and can sometimes increase stress levels, especially for women, as work and family spheres interfere with each other (Casaca 2002).

The drastic changes brought about by the pandemic and the need to reorganize paid work and housework are nevertheless an opportunity, as couples may be forced to adapt in the face of these new challenges (Arntz, Yahmed & Berlingieri 2020; Rosenfeld et al. 2020). The overrepresentation of women in key work settings (over 70% of healthcare workers - OECD 2020) may promote positive perceptions of men and legitimize women's work, both paid and unpaid. In cases where both members of the couple work from home, and even more so for couples with children, the need to negotiate the division of housework and childcare may become one of their main concerns, especially since the possibility of outsourcing this type of work was not available.

The studies conducted during the first period of the lockdown are not categorical, but most have shown that gender inequalities in housework and caregiving have persisted or even increased, depending on different variables (e.g., Craig & Churchill 2020; Del Boca et al. 2020; Dunatchik et al. 2021; Santos et al. 2021). In Australia, Lyn Craig and Brendan Churchill (2020) analysed data from a sample of 1536 parents in dual-earner couples during the May 2020 lockdown, asking participants how much time they spent on paid and unpaid work, including active and supervised care, and how satisfied they were with work-life balance and share of the burden. They found an overall decrease in paid work and a sharp increase in overall unpaid work during lockdown, mainly among mothers, and a relative increase in childcare by fathers. Overall, lower satisfaction was found, with mothers less satisfied with work-life balance (Craig & Churchill 2020).

These gender asymmetries were also found in two European Union countries, by Del Boca et al. (2020) in Italy, and by Santos et al. (2021) in Portugal, particularly among couples with underage children. The latter authors found, for example, that women reported doing much more work than was fair, both in housework and in caregiving. Parents reported higher workload in caregiving tasks compared with participants without children, regardless of gender. Del Boca et al. (2020) also showed that most of the additional housework and childcare associated with Covid-19 was performed by women, while childcare was more evenly distributed within the couple than housework. In addition, the authors emphasised that working women with younger children (0-5) were those for whom work-life balance was more difficult during Covid-19. More recently, EIGE has also shown that the pandemic crisis is widening the gender gap and increasing gender inequality in the labour market, with women being more penalised (Pereira 2021). Women were, thus, doubly penalised, both in the professional and domestic spheres.

In this article, we aim to clarify how the Covid-19 pandemic, and the resulting first lockdown in Portugal from March 18 to May 2, 2020, has affected the negotiation of unpaid work among mixed-gender couples, from the perspective of women. We anticipated that the burden of caregiving responsibilities resulting from school closures and increased housework would affect both women and men, but fall more heavily on women.

Following recent research (e.g., Amâncio & Correia 2019), we focus on who usually takes care of housework and caregiving, and how satisfied participants are with the division of these tasks. We also aim at understanding women’s perceptions about the causes of gender imbalance on share arrangements and what areas they found more challenging to balance during lockdown. As telecommuting was a major stressor, we also asked women the main advantages and disadvantages of working from home.

Considering our theoretical framework, parental status is present throughout our analyses. We seek to understand if women with and without underage children showed differences in i) who performs most housework within the couple; ii) who performs more caregiving tasks within the couple; iii) satisfaction with the way housework and caregiving are divided; iv) difficulty managing multiple activities during lockdown; and v) the impact of telecommuting.

3. Method

3.1 Participants

The study targeted Portuguese women (over 18 years old) living in a mixed-gender relationship. A convenience sample was obtained through the dissemination of a hyperlink on social media. A total of 171 female participants between the ages of 18 and 67 responded (M=36.71, SD =10.61), most of whom were highly educated (67.2% with higher education). Differences in degrees of freedom represent a small number of missing values in the variables analysed.

3.2 Procedure, instrument, and variables

Data collection was performed using a Qualtrics online questionnaire (Provo, UT), which was available in the second half of May 2020. General principles and practical guidelines described in first author institutions’ Code of Conduct for Research Ethics were followed (e.g., informed consent, anonymity of data, voluntary participation, contact information, and debriefing). Demographic questions were used as filtering criteria: age, gender, marital status, and work status (experience with home-based work).

Additional demographic questions were asked at the end of the questionnaire: educational attainment, estimated average monthly income, and estimated hours per week of paid work (see Table 1 for general demographic data).

Table 1 Demographic data: valid counts, variable distribution (in percentage), means and standard deviations (when applicable)

| Variables Measured | n | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 171 | - | 36.71 | 10.61 |

| Level of Education | ||||

| Secondary education or less | 11 | 6.43% | ||

| Graduated | 44 | 25.73% | ||

| Post-graduated | 71 | 41.52% | ||

| N/A | 45 | 26.32% | ||

| Legal marital status | ||||

| Single | 30 | 17.60% | ||

| Divorced | 4 | 2.30% | ||

| Married or de facto union (civil partnership) | 137 | 80.10% | ||

| Parental status | ||||

| Parent of underage children living in the same household | 61 | 35.67% | ||

| Not a parent of underage children or children don't live in the same household | 110 | 64.33% | ||

| Work status | ||||

| Not telecommuting (working outside of home, unemployed) | 20 | 11.70% | ||

| Telecommuting (presently or anytime during Covid-19) | 136 | 79.53% | ||

| N/A | 15 | 8.77% | ||

| Average estimated monthly income | ||||

| > 5,000 euros | 4 | 2.34% | ||

| >3,000 to <= 5,000 euros | 27 | 15.79% | ||

| >1,000 to <= 3,000 euros | 78 | 45.61% | ||

| <= 1,000 euros | 13 | 7.60% | ||

| N/A | 49 | 28.65% |

3.2.1 Assessment of the division of housework and caregiving responsibilities within the couple

Participants were asked who usually does the housework and caregiving tasks (“always/mostly me”, “both equally”, "mostly/always the partner”, or “another person [family, friends, neighbours, paid help]”). Questions about caregiving were general in order to compare parents of underage children with non-parents, who might have other caregiving situations (e.g., caregiving of elder/disabled family members).

3.2.2 Perceptions of changes in workload during lockdown

Participants were asked whether they perceived spending more or fewer hours on housework and caregiving compared to the pre-Covid-19 period. Answers were rated on a scale of 1 (much fewer hours) to 5 (much more hours).

3.2.3 Satisfaction with division of tasks

Participants were asked about their satisfaction with the division of (1) housework and (2) caregiving (two Likert scales, from 1=”very dissatisfied” to 5=”very satisfied”).

3.2.4 Main difficulties while telecommuting

To better understand the impact of the pandemic on couples' gender dynamics, quantitative variables were included to determine how several activities were balanced during the lockdown: (1) managing paid work, (2) managing childcare, (3) managing housework, (4) managing care for other family members, (5) balancing work and family life. Participants' responses were rated on a Likert scale (from 1=”much easier” to 7=”much more difficult” than before the lockdown).

3.3 Open-ended questions

3.3.1 Main reasons for the inequalities

To gain a deeper understanding of gender dynamics in task sharing, an open-ended question followed: "In your opinion, what are the main reasons for the inequalities between men and women in the sharing of housework and caregiving tasks?”

3.3.2 Perceptions of the advantages/disadvantages of working from home

Working from home represented a major change for the women participating in this study, and two qualitative questions were also asked that focused on their perceptions of the advantages/disadvantages of working from home.

Outside the scope of this study, additional variables were measured (estimates of time spent on housework and caregiving - own and partner - and perceptions of justice of these arrangements. These variables were analysed, and the results have been published elsewhere (Santos et al. 2021).

4. Results

Data were analysed considering sociodemographic variables (age, income, changes in occupational arrangement during Covid-19, and educational level) as covariates. None of these variables showed a significant role on the variables analysed. Therefore, the results are presented without covariates.

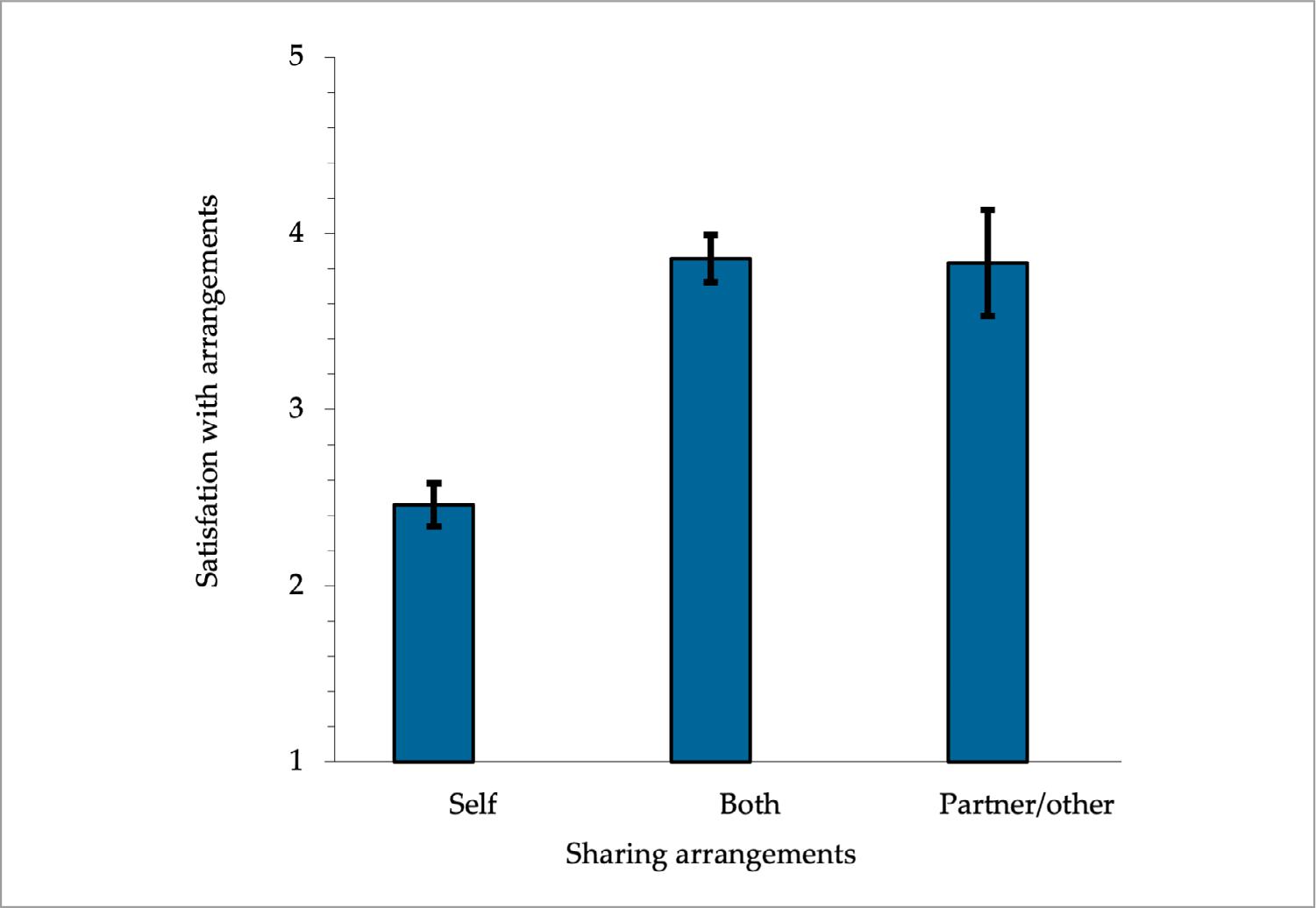

4.1 Perception of change in household workload

To understand how the workload of women who participated in this study changed regarding housework, a multivariate 3x2 GLM (General Linear Model) was performed using assessment of the extent of sharing (who usually performed these tasks before lockdown) and parental status (parenting underage child/children) as factors and perception of change in workload since lockdown, as dependent variable. While all women perceived an increase in workload (M=3.76, SD=.909), there was a general perception of higher increase for mothers (M= 3.97, SD =0.84) compared to non-mothers (M= 3.61, SD =0.93), F(1, 132) = 14.68, p >.001, η2p= .10, qualified by an interaction with who usually performed these household tasks, F(2,132) = 4.63, p=.011, η2p= .07 (Figure 1). Accounting for this interaction, simple main effects of parental status showed differences in women’s perception of increased workload in household tasks when those tasks were usually done by their partner before lockdown, F(1,132) = 13.02, η2p= .09, but not when tasks were done by both (p=.32) or by themselves (p=.30). Simple main effects on task division pre-lockdown showed differences in arrangements only for those who were not mothers of underage children F(2,132) =5.32, p=.006, η2p= .08, but not for mothers (p=.50).

Note: Estimated means and standard errors. Scale from 1= “Much less hours” to 5 = “Much more hours”.

Source: Authors’ own data.

Figure 1 Perceptions of change in workload regarding housework tasks, compared to pre-Covid-19, depending on sharing arrangements and parental status

Further analysis of the collective significant effect between pre-pandemic sharing arrangements and parental status revealed that, while all mothers reported an increase in time spent on housework (even those who did not perform these tasks before the pandemic), this was not the case for women without underage children. In fact, for these, and specifically when they were not primarily responsible for this kind of tasks before Covid, perception of time spent on domestic tasks was lower than before the lockdown.

4.2 Perceptions of changes in workload for caregiving tasks

A similar 3x2 GLM with sharing arrangements and parental status as factors and perceptions of changes in caregiving since the lockdown as the dependent variable showed no differences, neither main effects nor interactions (ps >.07). In fact, all women reported an increase in time spent caring for family members, even women without underage children, possibly older children, their partners, or family elders.

Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that women who reported a more equal sharing of caregiving responsibilities in their household, that is, where both members of the couple shared caregiving responsibilities equally in a pre-pandemic scenario, are the ones for whom the parental status showed a bigger impact. Pairwise comparisons corroborated a perception of higher increase in time spent in caregiving tasks in this subgroup of women. This implies that the presence of young children may be a factor that increases perceptions of inequality during the lockdown, as the additional childcare burden due to Covid-19 does not appear to be as evenly distributed as it was before lockdown.

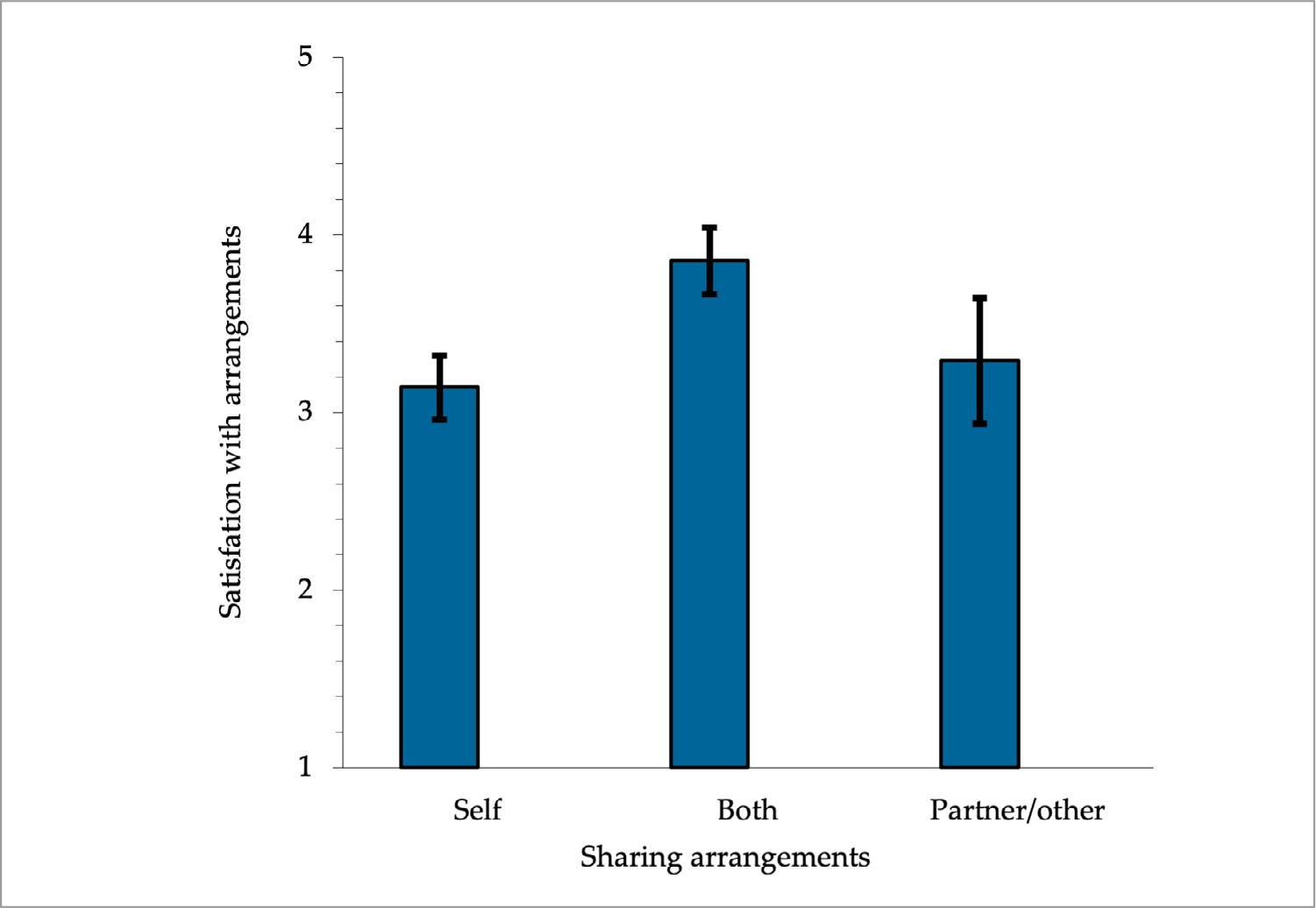

4.3 Satisfaction with the division of housework

A 3x2 GLM was conducted with sharing arrangements (who usually performed these household tasks) and parental status (underage children) as factors, and satisfaction with workload sharing since confinement as the dependent variable. There was an overall difference in satisfaction as a function of household arrangements F(2, 130) =32.23, p >.001, η2p = .33 (Figure 2), with higher satisfaction when tasks were performed by both (M= 3.90, SD =1.00), followed by tasks performed by partner or others (M= 3.82, SD =0.98), and significantly lower satisfaction when tasks were usually performed by themselves (M= 2.46, SD =0.97). There was neither a main effect of parental status nor an interaction (p >.62). That means that women who usually are primarily responsible for housework are highly dissatisfied with this arrangement, independently of the fact of being or not mothers of small children.

4.4 Satisfaction with the division of caregiving responsibilities

A similar 3x2 GLM was conducted with sharing arrangements and parental status as factors, and satisfaction with the sharing arrangements concerning caregiving since Covid-19 as the dependent variable. There was an overall difference in satisfaction as a function of arrangements, F(2, 78) =3.85, p=.025, η2p = .09, with higher satisfaction when tasks were done by both (M= 3.85, SD =0.93), followed by tasks taken on by the partner or others (M= 3.40, SD =1.17), and lower satisfaction when tasks were usually taken on by themselves (M=3.10, SD =1.19). Pairwise comparisons show that only the difference between being done by both and by themselves was significant (p=.008) (Figure 3). There was neither a main effect of parental status nor an interaction (ps >.12). This means that, similarly to the satisfaction with the sharing of housework, women who usually are the sole responsible persons for caregiving tasks are highly dissatisfied with this arrangement, independently of being or not mothers of small children.

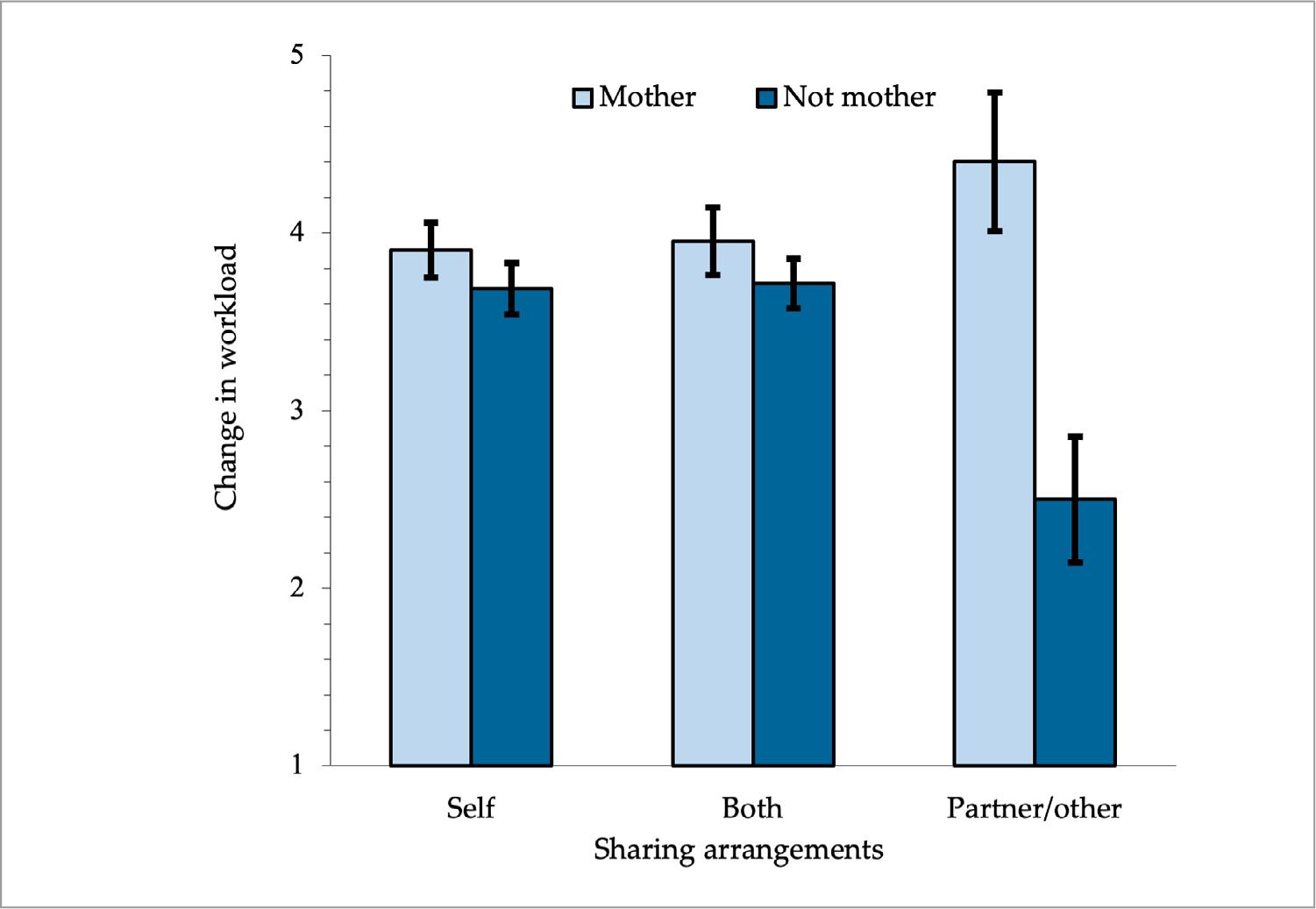

4.5 Perception of difficulties managing paid work while telecommuting

A 3x2 GLM was conducted using division of housework (who usually did these housework tasks before Covid-19) and parental status (mother/non-mother of underage children) as factors, and perceived difficulty in managing paid work while telecommuting as the dependent variable.

Maternal status and division of housework had an interactive effect on the perception of difficulties managing paid work while working from home F(2, 114) =3.22, p=.044, η2p = .05 (Figure 4.) Taking this interaction into account, simple main effects of parental status showed differences in the difficulty of working from home only when housework was usually done by both members of the couple, F(1, 114) =8.49, p=.004, η2p = .07, but not when the tasks were done by others (p=.18) or by women themselves (p=.31).

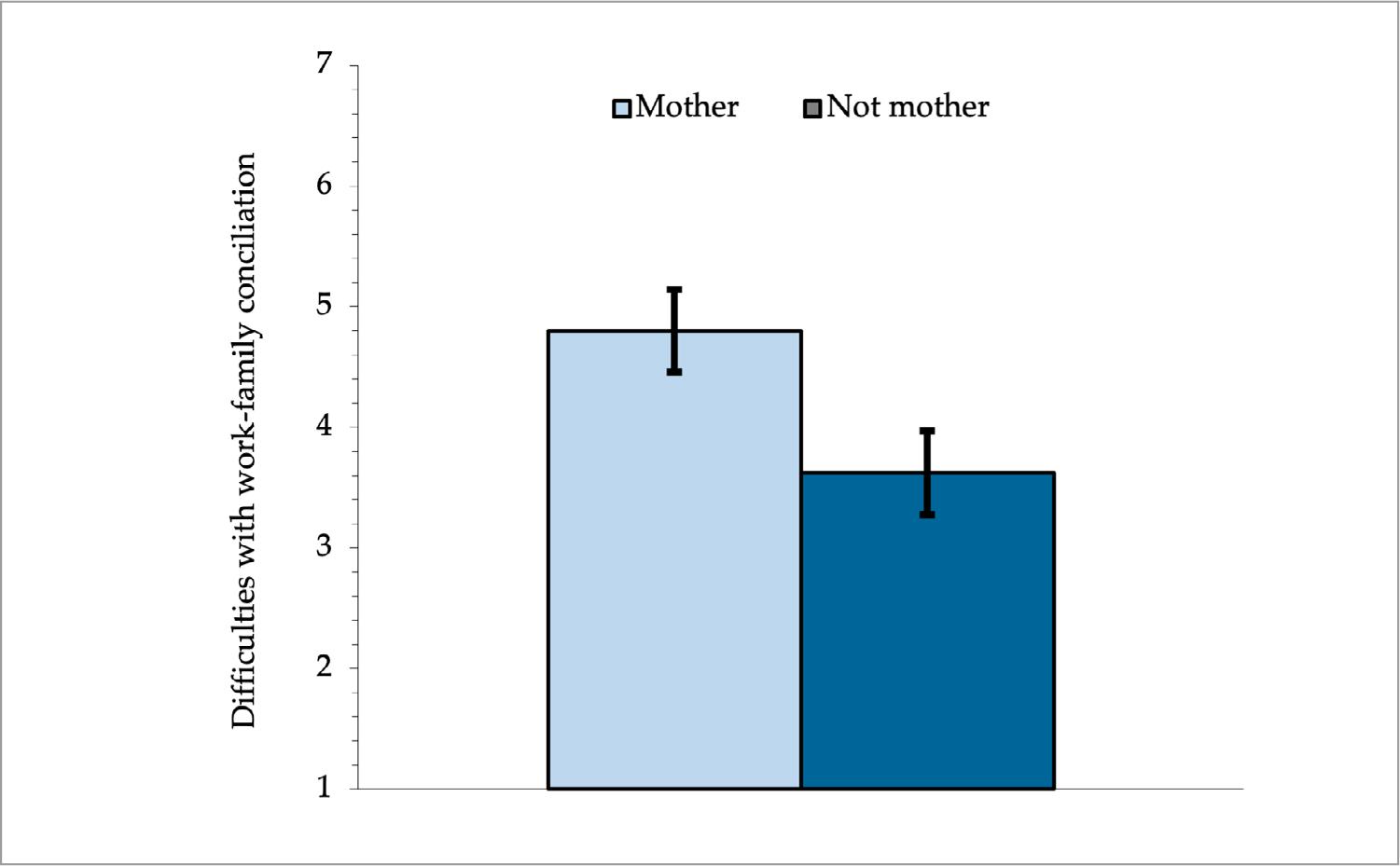

4.6 Perception of difficulties in work-family conciliation

Regarding the effects on work-family conciliation, a 3x2 GLM was conducted using division of housework (who usually did these housework tasks before Covid-19) and parental status (mother/non-mother of underage children) as factors, and perceived difficulty on managing work-family conciliation as the dependent variable. There was only a main effect of parental status (F(1,117) = 4.31, p=.04, η2p = .04) in the division of housework, with mothers of underage children expressing more difficulties (M= 5.09, SD =1.97) compared to other women (M= 4.03, SD =1.80) (see Figure 5).

Note: Estimated marginal means and standard errors. Scale from 1=“Much easier” to 7= “Much more difficult” than before lockdown.

Source: Authors’ own data.

Figure 5 Perceived difficulties with work-family conciliation, depending on housework sharing arrangements

Multiple 3x2 GLMs were conducted using division of housework (who usually did household tasks) and parental status (mother/non-mother of underage children) as factors, and other areas of perceived difficulty (managing caregiving, managing housework, managing other tasks) as dependent variables. No significant interactions were found. The same tests were conducted considering the usual division of caregiving (who was usually in charge of care) and parental status as factors. Again, no significant effects or interactions were observed.

4.7 Reasons for inequality in housework considering women’s satisfaction

To explore women's perceptions of the reasons for inequality between men and women in the division of housework, the sample was divided into two groups based on their level of satisfaction with their current division of housework. This split was based on the median (3.50), with the group above the median being the less satisfied and the group below the median being the more satisfied (see Appendix A1-A3).

The main differences in perceptions of the reasons for the disparity in the division of housework of the less satisfied group fell mainly on categories related to the presence of general socio-normative factors and gender stereotypes as the main causes of such inequalities (categories 1.1 and 1.2 with 44.07% and 27.12%, respectively). Women cited “cultural aspects and even modern families that perpetuate the idea that women are the caregivers” and reasons that are “due to cultural and gender role issues”, stating that “[...] there is still an inequality in the way domestic tasks are divided between men and women, with lower social and cultural expectations regarding the amount of time and type of tasks that men have to do in relation to domestic tasks”. These women clearly focused their rationale on historical social inequalities and complex dominance social systems.

The responses of the more satisfied group on the main reasons for inequality were mostly related to aspects of socialisation and upbringing, as well as essentialization, which refers to more innate dispositions that differ between men and women (mainly categories 1.3 and 2, with 37.04% and 29.63%, respectively). Examples of the justifications of this group were: “it is in women's nature to take care of the house and children more [...] it is their instinct as a woman and a mother”, but also “the way people are brought up”. This focus on nature versus nurture for these women seems to reframe the reasons for inequality on the intergroup level.

4.8 Advantages and disadvantages of working from home

To analyse the advantages and disadvantages of working from home, responses were evaluated according to whether participants had children.

Among the advantages of working from home, the most frequently cited by both groups (mothers vs. non-mothers) was the subcategory related to avoiding travel time and traffic on the way to/from work (subcategory 4.2, at 25.45% and 21.59%, respectively). The second most frequently cited benefit by both groups related to work-life balance (category 1), including the ability to spend more time with family, better organize housework, and better manage time. There were no notable differences between mothers and non-mothers in the reported benefits of working from home.

In terms of disadvantages, the most noticeable difference between groups was in the subcategory related to the creation of tensions between family, housework, and work (e.g., taking care of children during working hours, subcategory 1.1). In fact, 21.30% of mothers reported this disadvantage, compared to 4.24% of non-mothers of underage children. In addition, mothers were more likely to report the lack of adequate working conditions (13.33%) than non-mothers (5.56%). The most frequently reported overall disadvantage of working at home by both groups was related to the feeling of loneliness and monotony resulting from isolation (category 3.1). 14.81% of mothers and 20.61% of non-mothers reported this disadvantage.

5. Discussion

The aim of our study was to understand how women living in mixed-gender couples dual-earner households and working from home during the first wave of Covid-19 in Portugal perceived the change in workload related to housework and caregiving tasks. Overall, results show that housework workload perception increased for all women during the lockdown, except for childless women. Regarding caregiving tasks, the results were even more homogeneous. All women indicated that they perceived their workload to have increased, despite previous arrangements within the couple and despite the women's parental status. Women with young children who, in the pre-pandemic period, lived in households in which both members of the couple shared caregiving responsibilities, are the ones who show greater differences in their perceptions of increased workload. These overall results alert us to the fact that women were highly overworked during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, results also suggest that the presence of young children could be a factor of increased inequality during lockdown, as the additional burden of childcare due to Covid-19 could fall on women, even if this was not the usual arrangement. The fact that all women, including those without underage children, reported increased time spent on caregiving, sheds light on other realities not thoroughly explored in this article, namely the increased caregiving needs of other family members (e.g., older children, partners, elderly parents).

It is also noteworthy that the level of satisfaction with the division of household tasks is consistent with the results of studies published in the last 15 years on the division of housework within the couple (Stevens, Kinger, & Riley 2001; Amâncio 2007; Amâncio & Correia 2019). In general, women are dissatisfied with the division of housework, but this is especially true when these tasks are mainly performed by themselves, and this perception is not influenced by their parental status. The same general pattern was found regarding satisfaction with the division of caregiving tasks. Nevertheless, satisfaction was higher in households where tasks are usually performed by both members of the couple and lower when tasks are usually performed exclusively or mainly by the woman. When comparing more dissatisfied with less dissatisfied women in our sample, it is interesting to assess the possible psychological processes underlying the reasons for the disparity. Women who are more dissatisfied tend to cite sociological, structural, and systemic reasons that are beyond their individual control, whereas less dissatisfied women tend to cite reasons that are more related to group relations, socialization practices, and interpersonal factors and are therefore much easier to change soon.

Not surprisingly, women in this study reported difficulty working from home, caring for children, managing household chores, and supporting other family members during the lockdown. Parental status and division of tasks appear to be relevant only for women who work from home and have young children. These women expressed more difficulty in accomplishing these tasks when they used to be commonly shared before the lockdown, compared to when they were not responsible for these tasks before Covid-19, or even when they were solely responsible for this type of work. This is significant in that it shows that the additional workload comes with the added burden of couples having to negotiate how to divide their time during particularly stressful times. Consistent with recent research (Power 2020; Carlson, Petts, & Pepin 2021; Fisher & Ryan 2021; Santos et al. 2021), the results also show that it is particularly difficult to manage work from home and balance work and family roles when there are underage children in the household, especially in a labour market that expects full availability (Casaca 2013)

Although most women cited the advantages of working from home in terms of saving time by avoiding commuting time and traffic on the way to/from work, as well as being able to spend more time with family and better organise housework and time management, differences in disadvantages were also evident in women's discourse. Women with young children were more likely to report experiencing tensions between family, household, and work than women without children. Women without children tended to mention physical environmental characteristics, such as the lack of adequate working conditions, more frequently than women with children, who seemed to be less concerned about this issue.

Also important is the general mention of feelings of loneliness and monotony due to isolation. Mental health issues are cited as a major concern during the pandemic period, especially for women (Paulino et al. 2021), and overworked mothers are of particular concern (Prados & Zamarro 2020; Xue & McMunn 2021).

6. Conclusions

This study brings important insights to our understanding of family life during the Covid-19 pandemic, and especially to the situation of women during this period. Overall, its greatest strength lies in the combination of quantitative and qualitative data that give us important insight into the different realities experienced by women during the pandemic. This important contribution allowed us to understand the situation of women during the pandemic in a heterogeneous way and to break the traditional male/female dichotomy that prevails in traditional studies of the division of domestic tasks among mixed-gender couples.

Nonetheless, relevant limitations of this study should be addressed. Our sample is quite small and focused on women of childbearing age. In addition, it is biased toward educated women. The results may not be generalizable to younger or older women and to women with lower qualifications. It is possible that younger women living as a couple find that cohabiting greatly reduces the stress of family work and previous asymmetries in the division of domestic and caregiving tasks. It is also possible that older women found that caring for older family members increased their workload during Covid-19. These facts could not be considered in our study. Nevertheless, several studies published during the Covid-19 pandemic found little evidence that the division of domestic labour or changes in the amount of time women spent on chores during the pandemic varied by educational level (e.g., Carlson, Petts, & Pepin 2020; Chung et al. 2020; Shafer et al. 2020).

Finally, we were only able to address women's perspectives on this topic, and we used a narrow definition of gender in this study, primarily for comparative aspects, which limits the scope of our conclusions. A broader definition that includes non-binary approaches could be instrumental in understanding gender inequalities more thoroughly during Covid-19 (Fisher & Ryan 2021).

In spite of these limitations, our study showcases how in times of crisis, of which the Covid-19 pandemic is a mere example, gender equality suffers a rollback. This is an important lesson to take for potential crises to come.