‘Good and evil are the prejudices of God,’ said the snake. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

From the beginning men used God to justify the unjustifiable. Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses

Member of the assembled crowd (possibly Jesus himself): ‘Excuse me… Are you a Virgin? Mary (irately): Of course I’m a virgin…! Now piss off!’ Monty Python, Life of Brian

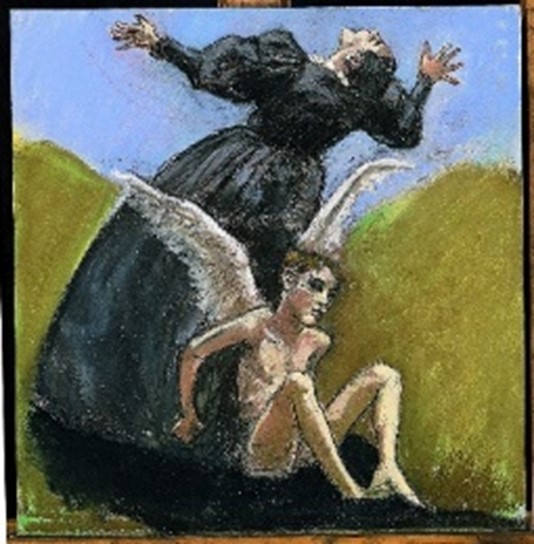

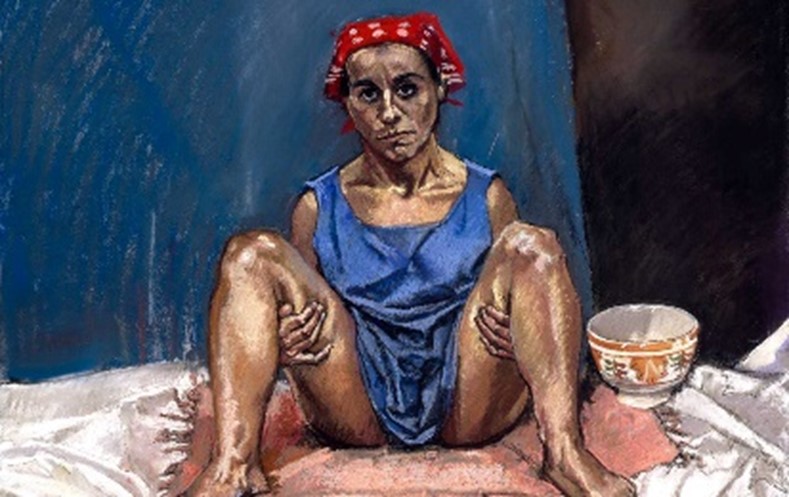

Awkward mothers: Agony in the Garden

As for those who state that it is thanks to a woman, the lady Eve, that man was expelled from paradise, my answer to them would be that man has gained far more through Mary than he ever lost through Eve. Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies

In Portuguese it is said that ‘mãe há só uma’ (there is only ever one mother) but in Paula Rego’s universe nothing is sacrosanct, not even (or especially not) mothers. Or at least not mothers in any normative sense of the word: which of course is what is always required on the part of the Judeo-Christian enterprise, even if defining motherhood requires the suppression of inconvenient variations of the concept, in the name of homely homogeneity.

Like it or not (historically predominantly not) many Portuguese are ethnically Jewish (Cooperman, 1998). Let us not forget that Salazar, who eloquently elucidated a woman’s role at the heart of the Deus/Pátria/Família status quo (with all its Nazi-inspired accoutrements: Kinder/Küche/Kirche) had on the paternal one of the surnames (Oliveira1) most commonly adopted by Jews forcibly converted to Christianity under Portugal’s three-hundred-year-long Inquisition.

But in Judaeo-Christianity, particularly on the Jewish side, mothers, it should also be noted, were not always all they ought to be,2 starting with the first one. Eve lost humanity Paradise, immortality, a life of eternal leisure, conjugal equality and, specifically in the case of women (with one later exception), the advantage of pain-free childbirth:

Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee. (…) In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground. (…) And he placed at the east of the Garden of Eden cherubim, and a flaming sword. (King James Bible, 1611, Genesis. 3:16-24)

Which was a great shame, of course, but first Adam had been warned, and second, as the song would have it, “the things that you’re liable to read in the Bible, it ain’t necessarily so…”. (Gershwin & Gershwin, 1935). Furthermore, Eve wasn’t even Adam’s/God’s first mistake. “One of the things that ain’t necessarily so” is the fact that the compilers of the Old and New Testaments may have told the truth and nothing but the truth (debatable) but not the whole truth. Instead, they set up a long and dishonourable tradition of censorship that banished to near-oblivion (definitely outside Eden) a whole corpus of inconvenient tracts only available in what are known as the Apocrypha3 and in certain Midrashic texts.4

And amongst these we find a reference to a first wife bestowed upon Adam by God, by name of Lilith. If you are supposedly both omniscient and omnipotent, creating a disobedient first wife might be seen as a misfortune, but to create two is definitely carelessness, or even unforgivable (snake and forbidden fruit will notwithstanding): a Divine version of ‘the dog ate my homework’?

In the Apocrypha Lilith was Adam’s first wife (McDonald, 2009) but she was a bad one and things went wrong from the start. She refused both to bow before him and to adopt the missionary position during sexual intercourse. As punishment she was banished to live on the banks of the Dead Sea where she consorted with demons and devoured the resulting male offspring. She is also associated with stillbirths, cot deaths, male nocturnal emissions, masturbation and erotic dreams:5 all instances of sex without issue. Not unlike like abortion, in fact. We/Paula will come to that presently.

Like Lilith, Eve, too, was expelled from Eden, but how typical of Paula that in her rendition of that event Eve is alone (no Adam), wept-for by an angel (rather than berated by cherubim with flaming swords), and seemingly on her way to pastures new:

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 1. Agony in the Garden (2003), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 76×70 cm.

For the last blossom is the first blossom And the first blossom is the best blossom And when from Eden we take our way The morning after is the first day. (MacNeice, 1982, p. 36)

In Rego’s Agony in the Garden only one figure seems to experience agony (grief). When Eve was expelled from Paradise (in Figure 1 Adam does not figure), the angels may have wept, but Eve herself seems to move with a spring in her step towards suspiciously (auspiciously?) rosy skies. Red sky in the morning, sailor take warning. Who is in peril on this particular sea? On a Lusitanian sea bordering a Christian, patriarchal, ocean-born empire? Who is pointing the finger of blame, and at whom? After the Fall the Garden of Eden was refurbished and became more than a lovely playground. Situated between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates (King James Bible, 1611, Genesis. 2:10) it later became Babylon. After God’s Law was broken by Adam and Eve it became the place where the first legal codes - human, not divine - were drafted (the Laws of Eshnunna, ca. 1930 BC; the Code of Lipit-Ishtar, 1934-24 BC; the Hammurabi Code, 1755-1750 BC). And it is also the site of modern-day Iraq, where in 2003 AD (very much in living memory), in the aftermath of 9/11 all kinds of laws from East and West were shattered in the name of two gods, civilization-by-whatever-name and peace on Earth. How is that turning out? By the rivers of Babylon we and the angels sat down and wept (King James Bible, 1611, Psalm. 137).

New beginnings: After the handmaid spoke

Behold the handmaid of the Lord King James Bible, 1611, Luke. 1:38

Eve: beautiful woman - I have seen her (…) she gave me a start, (…) stipulating quiet: ‘I should like to be alone;’ (…) ‘See her (…),’ the central flaw (…) that invaluable accident exonerating Adam. Marianne Moore, Marriage

In Agony in the Garden, the angel is wearing a dress of sunny hue, but her posture (Rego’s angels are almost always female, Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8) suggests mourning. Eve, on the other hand (we suppose it is she) is wearing sombre black garments previously worn by other figures: for example, Angel of 1997; and the apotheotic Virgin Mary in Assumption (2002), in which the angel (the only male one in Rego’s portfolio of angelology) is a small boy in danger of being crushed to death.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 2. Angel (1998), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 180×130 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 3. Assumption (2002), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 54×52 cm.

These images diverge in different ways from the standard iconography of angels or even from that in Rego (in the latter of which angels looming over a child-like Mary may lead to intimations - accusations - of child abuse: for example, the annunciation of her pregnancy to an under-age Virgin Mary, Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8). In standard annunciations, three common signs give rise to hermeneutic possibilities which Rego’s angels also challenge. First, the angel, across the art canon (from Simone Martini in the Middle Ages, through Botticelli in the Renaissance, to El Greco in the seventeenth century, to Rossetti in the nineteenth, to Alfredo Guttero in the twentieth), often holds out a white lily to Mary. The white lily is a symbol of purity and virginity. Less well-known nowadays (but the medieval and Renaissance artists may have been aware of this), the lily was a plant used in concoctions given to women as pain relief in childbirth (Gerarde, 1633, p. 191). Did these old masters not really believe that Mary, ‘alone of all her sex,’ (Warner, 2013) had escaped original sin and Eve’s punishment? Did she need pharmaceutical help after all? Whatever the case may be, in Rego there are no lilies and as demonstrated also in Nativity (Figure 10), there is pain in parturition.

Second, traditionally, but not in Rego, the angel visits Mary in a setting which whether indoors or out (a patio, a garden) features a pair of closed doors or gates (porta clausa, King James Bible, 1611, Ezekiel. 44:2), symbolic of her unruptured hymen.

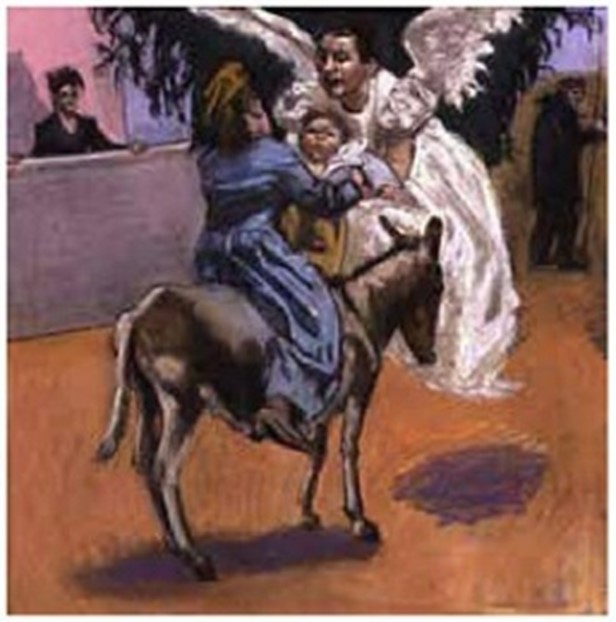

And third, she traditionally wears garments (either a dress or a veil) of what has become known as ‘Virgin blue’ or ‘Marian blue.’ Blue pigment, made from expensive lapis lazuli, was traditionally prized by artists as costly and hard to come by, and by the patrons that commissioned the art works as an exhibition of wealth (Baxandall, 1988). In a somewhat less commercial spirit, chemist Heinz Berke (2002) pointed out another reason for the favouring of blue pigment by artists: ‘early mankind had no access to blue because blue is not (…) an earth colour... you don’t find it in the soil.’ Blue, therefore, has spiritual (celestial) associations and is associated with the light necessary for sight (God’s inaugural fiat of the entire universe, Mary’s of her beholden body). In most (though not all) Rego’s Virgin images, however (Flight into Egypt, 2002, Figure 9; The Death of the Virgin, 2002), and particularly in Assumption (Figure 3: the occasion when, it is to be supposed, Mary finally shuffles off her mortal coil and takes up her place alongside the exclusively masculine Holy Trinity), the gown worn by her is dark blue/black (Figure 8 is the exception). In Assumption, furthermore - almost uniquely in her work - the angel is neither a powerful female figure nor the art canon’s customary towering transgender man-in-a-dress, but instead a small boy clearly not up to his role as a winged dumbwaiter to heaven. In this case no flights of angels sing/lift the Virgin to her rest: instead, as one would expect in Rego, Mary does it for herself.

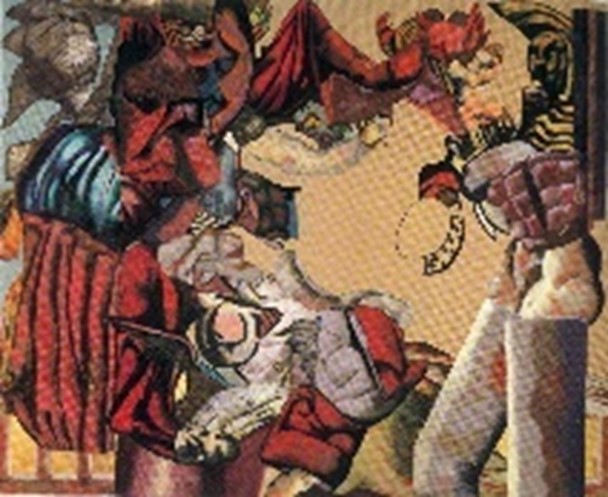

Over the years, Rego produced a number of Annunciations (Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8), including a somewhat cryptic one in the early eighties (Figure 4). None of them nor any of her other angels/Virgins are iconographically typical much less emotionally or semantically straightforward: enclosed spaces possibly, but no symbolic shuttered gates; blue garments, sometimes - albeit satanic blue/black rather than virgin blue; and, definitely, no lilies, only props such as a sword and sponge (Figure 2), usually associated with the Christ of the Passion. Although the latter, in Paula (Figures 11 and 12), is conspicuous for his absence where he might be expected to be the key player. In Rego’s annunciations Mary sits in a posture typical of little girls, wearing children’s shoes, ankle socks, with toes pointing inwards and looks much too young to be pregnant in any scenario that excludes abuse (and Mary possibly was so too6): a disturbing idea, unless “paedophilia” was taken to be the norm (which of course it may have been in Year Zero A.D. or even much later: ‘Younger than she are happy mothers made,’ Shakespeare, 1.2.12). Moreover, in at least one of them (Figure 8), there is an indistinct tableau in the background in which one of the figures appears to be weeping: possibly not unlike any young girl (including Mary herself), facing an unwelcome pregnancy, or like Rego as a young woman (is this a self-portrait?), contemplating an illegal abortion.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 4. Annunciation (1981), collage and acrylic on canvas, 200×250 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 5. Annunciation (2002), pastel and acrylic paint on paper, 54.5×52 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 6. Annunciation I (2002), pastel and acrylic paint on paper, 54.5×52 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 7. Annunciation (2002), pastel and acrylic paint on paper, 54.5×52 cm.

After the angel had left

Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world. King James Bible, 1611, John. 4:1

‘Evening, all! Gabriel’s the name, glad tidings is the game!’ Satan disguised as the Angel Gabriel Andy Hamilton, Old Harry’s Game

Glad tidings, of course, even if delivered by a bona fide spirit rather than a false prophet, almost always have strings attached. In Mary’s case they were twofold: first, how to deal with pregnancy if you are a) unmarried and b) supposedly a virgin; and second, the natural fears most women feel, even if the pregnancy was planned rather than imposed by outside interests (divine or otherwise).

Regarding the first, in Deuteronomy we learn that in the event of pregnancies out of wedlock ‘they shall bring the young woman out to the entrance of her father’s house and the men of her town shall stone her to death’ (King James Bible, 1611, Deuteronomy. 22:21). Not surprising, then, that when Gabriel visited uninvited, both Mary and Joseph (quite restrainedly in the case of the latter, considering the times that were) quibbled:

‘Then said Mary unto the angel, How shall this be, seeing I know not a man?’ (King James Bible, 1611, Luke. 1:35)

‘Joseph her husband, being a just man, and not willing to make her a public example, was minded to put her away privily.’ (King James Bible, 1611, Matthew. 1:19)

Typically (there are two exceptions: Pietá and Descent from the Cross, both of 2002) in Rego’s images on religious themes men do not figure even where they might be expected to have top billing. Joseph is entirely absent in The Flight into Egypt, Figure 9, and so is Jesus in Lamentation, Figure 10, and Deposition, Figure 11. As emphasized in an interview with Richard Zimler (2003), these images are about Mary. Particularly so when she gave birth, which in Rego, heretically, unlike in the Gospels, definitely involved pain (Figure 12). But Rego’s images are all about Mary even when Jesus by rights ought to take centre stage, for example in lamentations and depositions (Figures 10 and 11): ‘How can you do a crucifixion? If you do one it upstages everything. You cannot put it in this series. And it’s not necessary. The crucifixion is there in Lamentation, but it’s out of the picture. So you concentrate on Mary.’ (Rego cited inZimler, 2022).

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 9. Flight into Egypt (2002), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 54×52 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 10. Lamentation (2002), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 54×52 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 11. Deposition (2000), Deposition (1998), pastel on paper, 160×120 cm.

Which takes us to the second point of controversy: fear and pain. What woman, contemplating her pregnant body and the size of the bulk to be pushed down that narrow birth canal has not asked herself whether someone somewhere either miscalculated or deliberately sought to hurt her? Because hurt it certainly does, unless like Mary (but did she know in advance that she was to be the exception?) you are excused from the whole messy business.7 Paula’s Mary (Figure 12, Nativity), in any case, unlike the doctrinal one, is as much a daughter of Eve as any other woman.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 12. Nativity (2002), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 54×52 cm.

Richard Zimler: That pastel gives us the Virgin with her legs apart, suffering the pains (of childbirth).

Paula Rego: I think every woman feels it, that’s why we can identify with her. We all know it’s like that - to be pregnant (…) is upsetting and frightening. She’s frightened (…). If there is anything new about these representations of the Virgin, it is the fact that they were done by a woman) which is very rare. (…) It always used to be men who painted the life of the Virgin, and now it is a woman. It offers a different point of view, because we identify more easily with her. (Zimler, 2022)

Is Mary in this Nativity akin to the self-portrait of a scared, aborting Paula? We will come to that presently. If in Rego’s imagination Mary is relegated to the fate of Eve after the Fall (parturition in pain), no wonder that the angel/midwife that assists her is female. Men are excluded from the proceedings, and even the interested animal witnesses are female (no horns, therefore they are cows, not bulls). And why wouldn’t they be interested? They were all in it together. Over the centuries the Church Fathers stripped Mary of all that might signal her status as a biological human female: menstruation, visible pregnancy, painful childbirth and lactation (Warner, 2013). In Nativity, however, Mary is literally brought close to the animals that presumably helped keep her and her baby (wanted or not), warm on a cold December night.

Uncanny mothers: The Dame with the Goat’s Foot

Then said Saul unto his servants, Seek me a woman that hath a familiar spirit, that I may go to her, and enquire of her. King James Bible, 1611, Samuel. 28:7-21

A woman with a familiar spirit is a witch or succubus (female demon) by any other name, which makes Saul’s séance and request for advice in battle controversial to put it mildly: shouldn’t he have consulted God instead? In 2011-12 Rego produced a series of images based on a nineteeenth-century novella by Alexandre Herculano (The Lady with a Goat’s Foot, 1851) and a short story by Hélia Correia (Enchantment, 2004), the latter taking up the story line where Herculano - early advocate of women’s rights though he was - leaves female-shaped gaps in his narrative (Correia & Herculano, 2004). Both Herculano (a historian as well as a novelist known for his anti-establishment/anti-clerical writings) and Correia (a novelist and playwright prone to lampooning the classics for purposes that included the critique of the patriarchal, religious and geopolitical status quo) used a fictitious medieval text involving a woman with a cloven hoof for a foot to question all the sacred cows of Portugal’s identity: religion, territorial conquest and patriarchy: Deus, Pátria, Família. What is left at the end of each narrative is the wreckage of all that has underpinned the nation’s established understanding of itself since its birth in 1143.

All this, of course, is comfortable terrain for Rego to plant her own (satanic) cloven hoofs. And at the heart of her cycle of images, The Dame with a Goat’s Foot, as is indeed the case with Herculano and Correia, is the figure of the woman and mother. The Fascist leaders of the 1940s (Hitler, Mussolini, Franco and Salazar) saw the mother as the heart of the family, and where the family goes, so too does the nation (Salazar, 1939). In the case of this devilish mother and her bewitched homeland, it goes to a special kind of hell, in which men, fathers, patriarchs and Christian warriors find themselves in an unfathomable world: one in which mothers can be both diabolical and good; Muslim women and children are martyred without provocation at the hands of bloodthirsty Christians; warlords crave a return to the womb; and the dog of a Christian prince (not only his best but his only friend) is called Tariq: the name of the Muslim king who led the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 711.

Maria-Antonietta Macciocchi quotes Hitler as saying that ‘in politics, it is necessary to have the support of women, because the men will follow spontaneously’ (Macciocchi, 1979, p. 69). The enlisting of the female constituency was in-built into Salazar’s own grand plan. The crucial importance he attached to the promotion of family values as linchpins of social stability was emphasized repeatedly in the course of interviews and orations throughout the 1940s, 50s and 60s:

When we refer to the family what we have in mind is the home; and when we speak of the home we mean its moral environment (…). The work of the married woman outside her home (…) should not be encouraged.8 (Salazar, 1939, pp. 161-162)

Rego’s rendition of the tale of the cloven-hoofed Dame created by Herculano and elaborated upon by Correia has two focal points: first, the Lady herself, the embodiment of infernal yet appealing womanhood; and second, a trail of men, their interests, their rule and even their dogs, never again to be what they had been before they met and loved her. The canine component, in particular, must have appealed to Rego, famous for her attacks on dogs (Figure 15) which, as she had said in the past, in her images always represent men (Rego & Bessa-Luís, 2001), and for her ferocious dog women whose bite is even worse than their bark.9 In Herculano and Correia, the unleashing of events that wreck the stability of the family, Church and State is triggered when the husband’s male hunting dog is killed by the wife’s female poodle, which, having slaughtered the huge hound, disappears like her mistress, never again to be seen in Christian lands. Whether in Herculano, Correia or Rego, an (under)dog is not the same as a bitch.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 13. Dame with the Goat’s Foot III (Death of the Hunter’s Dog) (2011-2012), pastel on paper, 150×170 cm.

It takes one Dame (Dame Paula Rego10) to know another. When was the last time anyone checked Rego’s feet and lived to tell the tale?

This is my son with whom I am not well-pleased: Amélia or the abortion option

At the Slade, (…) girls would often be talking about where to go to get abortions. We were always falling pregnant. Later (…) when we were living in Ericeira, women would come to our gate to beg for alms (…). It was almost always for abortions. (…) It affected the poor disproportionately. If you were rich it was easier to find a safe way to have an abortion, usually by travelling to another country. Poor women were butchered. Paula Rego, Girls never get pregnant at the Slade School of Fine Art

Your legal career is but a means to an end, and that end is building the kingdom of God. Amy Coney Barrett, anti-abortion Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

Behold a voice out of the cloud, which said. This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased. King James Bible, 1611, Matthew. 17:5

Of course not all children are welcome. In 1997 Paula Rego produced a series of pastels inspired by Eça de Queirós’ nineteenth-century novel, The Crime of Father Amaro. The novel, one of the fiercest anti-clerical remonstrations in literature and praised as such by such luminaries as Émile Zola, tells the story of priestly corruption in a Roman Catholic status quo and narrates the seduction of a young woman by her priest, her pregnancy, her death in childbirth and the murder of the inconvenient baby. Unwanted pregnancies, then, and the (im)possibility of their termination, were clearly on the mind of Rego, herself always open about her own (in the 1950s illegal) abortions when she was a student in London. In the novel, the guilty priest and his mentor, discussing how to deal with the consequences (to Amaro, a priest bound by vows of celibacy) of the pregnancy, consider (only to dismiss it), the possibility of an abortion. In the event, Amélia fortuitously dies in childbirth, which only leaves the disposal of the infant to be arranged. Ironically (particularly in the case of two Catholic priests: presumably ‘pro-lifers’ opposed to contraception, let alone abortion), the solution is the murder of the new-born infant. Her immortal soul notwithstanding, an early clean abortion might have saved Amélia’s life: a possibility mentioned by the aptly named Dionísia (former town prostitute who now works as Amaro’s domestic servant and also doubles up as the facilitator of illicit affairs: she knows how to arrange convenient venues for sex, procure abortions and outsource the disposal - infanticide - of unwanted offspring).

In Eça’s novel Amaro’s emotional turmoil never really involves guilt about his broken vows, only his desire to reconcile sexual desire with the social privileges that accrue to being a priest; and following Amélia’s death he quickly rallies, moving on to a richer parish where, having learned his lesson, he now follows a policy of only having affairs (‘confessing’) married women, on the principle that he who is husband is father (Pater est, quem nuptiae demonstrant).

Interestingly, in Rego’s rendition, Amélia’s death is left out of the narrative. Instead in Coop (Figure 14) the birth scene is akin to a literal (and merry) hen party. Even when her inspiration is a source in which a woman dies, in Rego she does not, or - as is the case in The Maids, from Jean Genet’s play of 1947, itself based on a real-life murder - the model for the victim is a woman made up to look like a man in drag. The Father Amaro series also includes a possibility (that of Amélia’s dream/revenge, Figure 15) entirely unscripted in the novel. This is an image whose title and mise-en-scène say it all, particularly in the case of an artist who has stated that when she uses dogs in her images what she is depicting is men (Rego & Bessa-Luís, 2001).

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 14. Coop (1997), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 150×150 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 15. Amélia’s Dream (1997), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 162×150 cm.

In 1998, the year after the creation of the Father Amaro pastels with their associated themes of unwanted pregnancy, infanticide and maternal death, came the abortion pastels (Untitled). That year Portugal was bitterly divided on the issue of the legalization of abortion. In 1940 the Salazar regime had signed a Concordat with the Vatican under Pius XII (‘Hitler’s Pope’, Cornwell, 1999). The law of the Church had become the law of the State, with all that entailed in matters such as women’s rights, divorce, contraception and abortion. Under the Concordat the prevailing ideology fully endorsed the role of what Maria Antonietta Macciocchi called ‘Fascism’s fertile mother’ (Caplan, 1979, p. 62; Macciocchi, 1976). Not surprisingly, therefore, the country enforced one of the strictest abortion laws in the Western world. Abortion was illegal and punishable with a term of imprisonment. Backstreet abortions constituted the third most common cause of maternal death.11 An attempt to decriminalize abortion in 1998 was successfully blocked in a referendum by massive lobbying on the part of the Roman Catholic Church and right-wing interests.12

Despite legislative changes implemented in 2007 which de-criminalized abortion up to ten weeks, in practice many doctors continue to refuse to perform the procedure on grounds of conscience, which can still make medical abortion unobtainable. The Carnation Revolution of 25 April 1974 had re-established democracy in Portugal, opening the way for significant changes in women’s lives. The events surrounding the referendum on abortion in 1998, however, made clear the extent to which, even a quarter of a century after the abolition of Roman Catholicism as the official state religion, clerical influence and regressive attitudes concerning women and motherhood still endured in the national psyche.

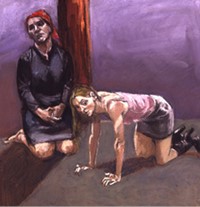

Enforced maternity was very much a reality in Portugal in 1998 and Paula Rego’s Untitled (silenced) works, created in protest against the Church’s actions, spoke loudly about her anger at attitudes that prevailed then (and to a lesser extent still do now).

Even prior to the events of 1998, her attacks on the alliance of Church and State and the life-and-death consequences of their collusion, both under Salazar and subsequently, had found expression in her work (including in the Father Amaro series of the year before). Even earlier, in 1981 she had produced a cryptic work (Annunciation, Figure 4) which, inasmuch as the quasi-abstract style permits interpretation, appears to depict Mary facing a mechanical set of iron pincers (possibly representing the Angel Gabriel) looming over her, ready to take possession of her consenting or non-consenting body (six centuries after his alter ego, the Angel Jibrīl, branched out to dictate the Qur’an to the Prophet Muhammad with analogous implications for Muslim women13). Religious themes returned on a regular basis in the decades that followed, including in the works of 2002/2003 already discussed. At the heart of them is the issue of motherhood and of women’s bodies. Rego, having herself undergone more than one illegal abortion whilst an art student in London, identifies with the plight of working-class women in Portugal during her childhood: “I know what am talking about. (…) I saw the wretchedness of the women (… in Portugal). (The pictures) are about things which we must continue to do in secret, as ever” (Rego cited inPinharanda, 1999, p. 3). ‘In secret, as ever:’ is that the meaning of the small watch discarded on the floor by the abortee in Figure 16? Somethings are timeless and never change: unless we change them of course, so that girls wearing school uniform and ankle socks (Figure 17) no longer need to bleed and sometimes die alone. Are you still with us, Jane Roe?14

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 16. Untitled (1998), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110×100 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 17. Untitled (1998), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110×100 cm.

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 18. Untitled (1998), pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110×100 cm.

Rego’s series on abortion (the images she stated made her proudest of all in her extensive body of work) run the full gamut from fear and pain to defiance and assertiveness (Figure 18). Perhaps those pincers in the Annunciation of 1981 (Figure 4) were actually the instruments of an abortion that in the end the child Mary could not obtain. Instead she became the mother of God: even in Rego there isn’t always a satisfactory resolution for women, let alone girls, and metallic instruments are more often than not put to use for the exclusive convenience of men. In the section that follows she restricts herself to pain (female) and pleasure (male).

Genital mutilation: Pleasure is not a woman’s business

Never trust a creature that bleeds for one week every month and doesn’t die. Neil LaBute, In the Company of Men

As my mother once said: the boys throw stones at the frogs in jest. But the frogs die in earnest. Joanna Russ, The Female Man

Let a woman learn quietly with all submissiveness. (…) She is to remain quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve; (…) the woman (…) became a transgressor. Yet she will be saved through childbearing. King James Bible, 1611, Timothy. 2:11-15

In Timothy, above, the woman will be saved through childbearing, but only as long as she suffers for it. Hence the enduring debate not just in theological circles but in medical ones too, which for centuries debated whether or not to give pain relief to women in childbirth, since pain was their sex’s atonement for the sin of Eve (Bourke, 2014; Pope Pius XII, 1956; Skowronski, 2015). Genital mutilation, sometimes euphemistically misnamed as female circumcision, is an old tradition in some parts of the world. The term ‘tradition’ of course encompasses rituals that historically have included the stoning to death of lepers, the burning at the stake of Jews, the ducking of witches and the hanging, drawing and quartering of traitors. They all share common ground: pain, violence and death in the name of the greater good. The motivation for performing genital mutilation upon girls may be to guarantee pre-marital virginity or to enhance male sexual pleasure (a tight vagina), or both. Or to cater to the pure or garden-variety delights of misogyny regarding the spectacle of the pain of (female) others.

Even international organizations working towards eradicating this crime can be curiously mealy-mouthed about it, avoiding a lexicon of criminality against women and sheltering behind concepts of customs and cultural differences to describe the mutilation of the bodies of pre-pubescent female children for two main purposes: first that of safeguarding their bodies as the property of men; and second the maximization of the latter’s sexual pleasure, predicated upon female pain:

Girls undergo female genital cutting (FGC) as a result of deep-rooted tradition among practising communities. The practice is a social norm that is held in place by an entire community; men and women alike. FGC is often a tradition that is passed down through generations, meaning that parents often unquestioningly have their daughters cut because the community expects it. Also referred to as female genital mutilation (FGM), the practice of cutting girls is frequently based on a traditional belief in the need to control a girl’s sexuality and ensure her virginity until marriage, or to prepare her for marriage. A girl who remains uncut will often be considered unsuitable for marriage. There are also often misconceptions that an uncut girl will be promiscuous, unclean, bad luck, or less fertile. In some communities, there are also misconceptions that it is a religious obligation to cut their daughters. (Barnardo’s., n.d.)

The World Health Organization informs us that:

Sex, (necro)politics, religion, (bio)power abuse, misogyny, violence: from Paula Rego’s point of view, what’s not to hate? As ever, her titles are an important weapon in the battle. Asked about the women’s issues that she tackles in her work (sex trafficking, illegal abortion, and genital mutilation) Rego stated that ‘emotions don’t have to come into it. I feel what I feel but that’s it. I’m trying to get the picture to be as near the truth as possible. (…) I read a lot of books (…) and they had a great influence on me. (…) I became aware of things that I hadn’t been aware of before (…). It was exciting to think that women could do what men could do. It felt just. (…) I try and get justice for women... at least in the pictures. Revenge too.’ (Gosling, 2018)

Women, of course, don’t always stand together. Traditionally girls are taken by their mothers or grandmothers to the mutilation ritual that ‘culturally’ is deemed to be part of ‘becoming a woman.’

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 19. Night Bride (2009), etching and aquatint on velin arches paper, 36.5×50 cm.

In the end, however, respect for so-called cultural diversity (in this case aka as violence) notwithstanding, Rego can’t quite follow through. Just as in The Maids of 1987 she couldn’t bring herself to depict woman-on-woman violence,15 so in Escape (Figure 20) of 2009 a mother takes her little girl away from the mutilating knife:

Credit: Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro © Ostrich Arts Ltd.

Figure 20. Escape (2009), watercolour, etching and aquatint on paper, 64×50 cm.

In the end, as ever, in Rego women look after one another. If necessary, to the death, although with any luck not their own. Sometimes they get away. Even with murder (Figure 15). ‘Revenge too.’