Professionals working in pre-hospital emergency contexts are confronted with very demanding activities, which increases the risk of developing certain health conditions (Donnelly et al., 2014; Kleim & Westphal, 2011; Sterud et al., 2006). These professionals are more vulnerable to work-related stress (van der Ploeg, 2003) and to the possibility of developing mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (Petrie et al., 2018; Sterud et al., 2006). Stressful environments can cause low job satisfaction and disengaged behaviours in professionals, which may lead to turnover, absenteeism and lower job performance (Rantanen & Tuominen, 2011; Setti et al., 2018) among others. Social support is broadly considered to be a protective factor for mental health (Brooks et al., 2016; Mildenhall, 2012; Prati & Pietrantoni, 2010; van der Ploeg, 2003), especially against the impact of stressful situations (Scully, 2011). The negative effects of potentially traumatic events and occupational stress seem to be mitigated by the perception of a good social support network (Oginska-Bulik, 2015). Peer support is a component of social support, having been originated about 40 years ago. Influenced by the mental health consumer movement of the 1970s, it empowered former mental health service users to help each other (Davidson et al., 2012). Peer support stands for offering support to a colleague who shares the same experiences and “speaks the same language” (Repper et al., 2013). It is based on principles of confidentiality, respect, mutual agreement and reciprocity (IFRC Reference Centre for Psychosocial Support, 2012; Repper et al., 2013; Sunderland & Mishkin, 2013). Some systematic reviews reported potential peer support benefits applied to different contexts and target groups, such as people with specific health conditions (Haines et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2020) or other specific populations, such as bereaved people (Bartone et al., 2019). Moreover, different studies suggest the benefits are extended to both parties involved, receivers and providers (Davidson et al., 2012; Repper et al., 2013). The main benefits of peer support interventions are the improvement of confidence, knowledge, general health perception, well-being, and quality of life (Pfeiffer et al., 2011; Solomon, 2004). In addition, these interventions can enhance hopefulness, self-esteem, self-control (Repper et al., 2013), problem solving, decision-making skills (Repper et al., 2013; Solomon, 2004) and positive meaning in life (Bartone et al., 2019). Considering the organizational dimension, peer support seems to contribute to a supportive work environment (Curling & Simmons, 2010). Not only does it boost productivity, attendance and retention, but it is also a valuable and relatively low-cost resource, providing good return on investment (Beshai & Carleton, 2016; Huang et al., 2020; Pfeiffer et al., 2011). Repper et al. (2013) highlighted that peer supporters can bring multiple benefits for the organizations if appropriately recruited, trained and assisted. Moreover, it fosters social support and engagement (Haines et al., 2018), as well as promotes camaraderie among members and increases staff morale (Masi, 2005).

Specifically with first responders, this methodology tends to be used more as a component of crisis-focus psychological interventions than for stand-alone programmes (Beshai & Carleton, 2016). It is an approach valued by first responders (Grauwiler et al., 2008; Prati & Pietrantoni, 2010) and it seems to be an important factor to facilitate emotional decompression from particularly stressful interventions (Carvello et al., 2019). Furthermore, it enables an early identification of who may be in need of some specialized help, and encourages them to seek mental health support (Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2012), thus minimizing the stigma associated with mental health issues (Beshai & Carleton, 2016; Faulkner & Basset, 2012), and preventing or decreasing the severity of psychological distress (Hugelius et al., 2014; Sterud et al., 2006).

Despite its value and applicability to a wide range of contexts (Doull et al., 2019; Repper et al., 2013), and the value reported by various studies, research on well-defined and evidence-based structure, as well as peer support effectiveness, is scarce. Beshai and Carleton (2016), in their review, identified articles describing programmes currently offered within departments across North America, Europe, and Australia. The authors found limited empiric evidence about the effectiveness of any peer support programme to reduce or prevent psychological symptoms experienced following critical incidents; and no robust evidence to suggest peer support programmes or specific crisis-focused psychological intervention programmes are harmful to first responders when implemented in accordance with the programmes described in the academic literature (Beshai & Carleton, 2016). Specifically considering those who work in the pre-hospital emergency services, Creamer et al. (2012) carried out a Delphi method study with a group of international experts, from 17 countries, working in the field of peer support, which has enabled a set of evidence-informed recommendations for peer support use, on areas such as: 1) goals of peer support; 2) selection of peer supporters; 3) training and accreditation; 4) mental health professionals; 5) the role of peer supporters; 6) access to peer supporters; 7) looking after peer supporters; and 8) programme evaluation.

Therefore, considering the scarce literature on the effectiveness of peer support programmes, with this study we aim to evaluate the impact of a Peer Support Programme (PSP) within a group of ambulance personnel. Participants completed pre- and post-intervention questionnaires regarding job satisfaction, general health and well-being, as well as perceived social support. We hypothesized that participants who enrolled in the PSP would report improvements, when compared to those who did not participate. In addition, we expected that ambulance personnel who participated in the PSP would report improvements from pre-testing to post-testing. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of a peer support intervention in a pre-hospital context in Portugal.

Methods

We conducted a quasi-experimental study for seven months, with a pre-test evaluation, followed by the intervention and a post-test evaluation, with three groups of ambulance personnel: a peer support providers group (PG), an experimental group (EG) and a control group (CG).

Participants

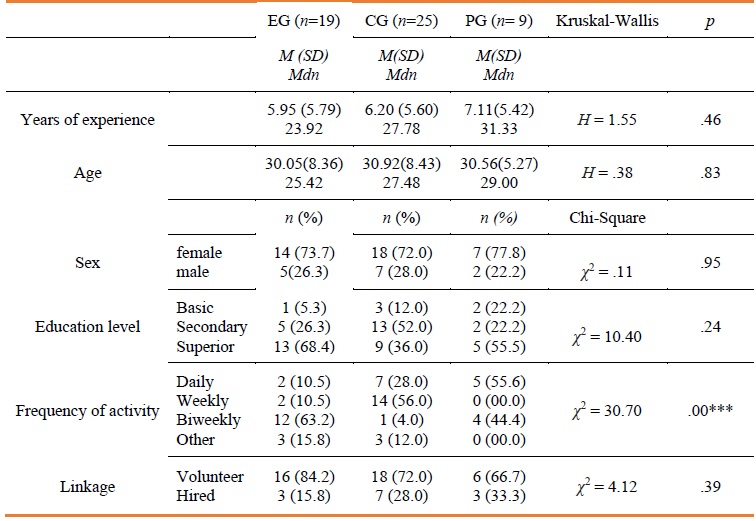

The total sample consisted of 53 ambulance personnel, of which 19 belonged to the EG, 25 belonged to the CG and nine participants belonged to the PG - i.e. ambulance personnel who received specific training to provide support to their colleagues of the EG. Sociodemographic variables and variables related to the Red Cross are presented in Table 1. We explored the differences between the experimental, control and peers groups on demographics, health, and Red Cross variables (Table 1), and significant differences between groups were found only in the frequency of activity in the Red Cross, χ2 (10, N=53) = 30.70, p = 0.00.

Procedures

The research project was approved by the Portuguese Red Cross and by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences of the University of Porto. We conducted a previous qualitative study in order to have a better understanding of this prehospital emergency context, and to collect some suggestions on how to support first responders, including on how to develop a peer support system (Oliveira et al., 2019). We integrated both data from first responders and international recommendations (Creamer et al., 2012; Inter Agency Standing Committee, 2007; Repper et al., 2013; Sunderland & Mishkin, 2013). Two branches of the chosen institution were selected by convenience and were invited to participate in the study, having accepted. We sent a cover letter, explaining the aim of the study, the procedures, the voluntary participation and the possibility to withdraw at any time. According to the general data protection regulation and the Code of Ethics of the Order of Portuguese Psychologists, we also assured the compliance with ethical issues and data protection.

Before the beginning of the PSP, job satisfaction and the related affective well-being, general health and well-being, as well as perceived support were measured through different questionnaires, as explained below. These measures were completed during the same time period by ambulance personnel from the EG, CG and PG. At the end of the study, overall results were returned to both branches.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and Health Variables and Differences Between EG (n = 19), CG (n = 25) and PG (n= 9)

Note: *** p value < .001

In order to select the participants for the EG, we started by presenting the project to all ambulance personnel of the local emergency structure, in a plenary session. All participants agreed to participate in the study and signed the informed consent. From a total of 30 ambulance personnel, 19 showed interest in being a peer. Later, we called each candidate who showed interest, to evaluate their expectations, to explain with more detail the role of a peer, the goals of the training and of the PSP, and to answer their questions. One of the authors (AO), specialized in clinical Psychology, made this contact. According to their experience, skills and availability, nine participants were selected and attended the peer support training, developed by one of the authors (AO) and the PSP mental health professional, who occupied the position of clinical director and was also involved in supervision, as recommended (Creamer et al., 2012). This training occurred over two consecutive days, focusing on topics such as stress, coping, psychological trauma, resilience, posttraumatic growth, communication skills, psychological first aid, peer support, self-care, referrals, protocols of peer support intervention, follow up, and ethical issues. This training involved learning topics and putting into practice procedures through individual exercises, group tasks, and role-play exercises. For professional reasons, two of the nine peers left the branch and, consequently, the PSP, midway. Different materials (e.g., algorithms, forms, videos, posters) were available to supporters, in digital, electronic and paper form, and released regularly, in order to recycle knowledge and analysis, and discuss practical cases. We developed informative posters and made them available in common work areas of the branch, so all ambulance personnel were informed.

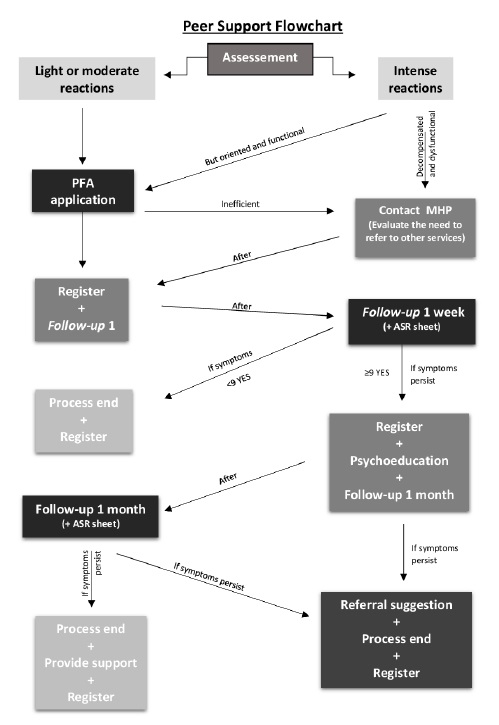

The procedure to initiate a peer support action could happen as a response to a mandatory activation, considering a list of typical critical events (e.g., cardiac arrests, deaths); by peer supporters’ own initiative, when they observed someone who presented warning signs; or by direct request. During their intervention, in order to boost the psychological well-being of the workers being supported, the main goal was to identify stress reactions (e.g., anxiety, fear, anger, denial, blame, withdrawal, disorientation), to evaluate needs, and to provide support, facilitating emotional and cognitive processing of working-related events. Psychological first aid was used to stabilize acute stress reactions, to provide practical information, to promote adaptive coping strategies and to promote the connection to their support network. If deemed necessary, peers could make a referral to the PSP mental health professional. After the first intervention, a week after the event, according to the flowchart (Figure 1), supporters had to make the first follow-up. If some symptoms (e.g., sleep patterns, job performance, psychological and somatic complaints) persisted and interfered with normal functioning, a second follow-up would be scheduled, up to a month after the event. If the symptoms persisted at the second follow-up, a referral to the PSP mental health professional would be suggested.

During the PSP, a mental health professional maintained close contact with peer supporters, by monitoring them, making informative materials available on a regular basis, giving feedback on how their activities were going and offering assistance if needed. Electronic communications were also used for this purpose, including mobile phone, email, and chat programmes. After each intervention, peers submitted an electronic form, with information about the event, symptoms, needs and procedures. This registration made the monitoring possible by the researcher and the PSP mental health professional. During the programme, from a total of 21 critical calls, 35 ambulance personnel received peer support, 34 of whom had a single time follow-up and just one member had a second follow-up. Thirty-two interventions took place after mandatory activation, two activations occurred after direct requests, and only one activation was made by peer supporters’ own initiative. There was no need for referral to PSP mental health professionals or other specialized services.

Measures

Job Satisfaction Scale - JSS (Portuguese version - Wilks & Neto, 2013): The JSS is a 16-item scale where respondents are asked to rate their degree of satisfaction with each item, on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 - very unsatisfied; 5 - extremely satisfied). A mean total score of items is computed and higher values indicate higher satisfaction. The Portuguese version of the JSS presented a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .91. For this study, we removed the item related to pay, because, in this institution, first responders could be employees or volunteers. In this study, the JSS presented a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .92.

Job-related Affective Well-being Scale - JAWS (Portuguese version - Wilks & Neto, 2013): The JAWS is a 12-item scale, with six positive feelings and six negative feelings. Respondents are asked to report how they feel at work, on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 - not at all; 5 - extremely). The negative feelings items are reverse-scored and a mean total score is computed, with higher values indicating greater well-being. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the Portuguese version was .75. This study shows a Cronbach’s alpha of .84.

General Health Questionnaire 28 - GHQ-28 (Portuguese version - Pais & Antunes, 2003): The GHQ-28 is a self-report questionnaire that evaluates mental health and psychological well-being on four subscales: somatic symptoms (GHQ-28 SS); anxiety/insomnia (GHQ-28 AI); social dysfunction (GHQ-28 SoD), and severe depression (GHQ-28 SeD). Each item can be rated from 0 to 3 (0 - not at all; 1 - no more than usual; 2 - rather more than usual; and 3 - much more than usual), with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 84. Higher scores indicate higher levels of distress and worse mental health. Total scores above 23 suggest a need for clinical assessment. The original scale reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .82 to .86. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient varied between .78 and .89.

Perceived Organizational Support and Perceived Colleagues Support - POS, PCS (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002): The POS evaluates employees’ perception concerning the extent to which the organization values their contribution and cares about their well-being (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). The original scale is composed of 36 items. However, because it is unidimensional and has high internal reliability, the use of a shorter version does not appear problematic (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). We used an eight-item scale, in which respondents rated their agreement with each statement using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 - strongly disagree; 5 - strongly agree). A mean score of total items was calculated to show the level of perceived support. To assess perceived colleagues’ support (PCS), we adapted the POS by replacing the term “The Red Cross” with the word “colleagues”. The original POS scale exhibits a .97 Cronbach’s alpha. In this study, the instrument exhibits good levels of internal reliability (.90 for POS and .93 for PCS).

Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using the software Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25. The normality was determined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and it was not met. Considering this assumption violation, baseline characteristics between the EG, CG and PG were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis H-Test for continuous variables and Chi-square Test for categorical variables. In order to verify the effect of the PSP on the studied variables, considering the pre-test and post-test, differences between groups were tested with Kruskal-Wallis. To compare the pre-test and post-test scores of the groups, considering them as paired groups, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Results

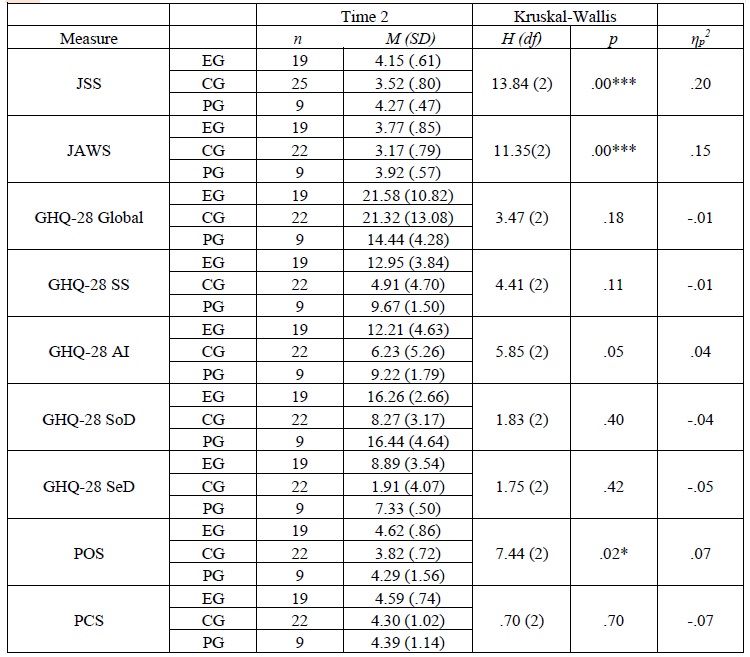

At the baseline, there were no differences between the EG, CG and PG regarding all measures. After PSP implementation, the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated a significant difference between groups, on JSS [H(2) 19 = 13.84, p =.00, .20, ηp2 = .20], JAWS [H(2) = 11.35, p = .00, ηp2 =.15] and POS [H(2) = 7.44, p = .02, ηp2 = .07]. These results are displayed in Table 2. Post-hoc analyses indicated that JSS values were higher at Time 2 for participants of both EG [H(2) 19 = 14.52, p = .004] and PG [H(2) 19 = 16.96, p = .010], when compared with CG. Moreover, analyses showed higher JAWS values in EG [H(2) 19 = 12.83, p = .015] and PG [H(2) 19 = 15.84, p = .018], when compared with CG. In addition, analyses also showed higher values of POS in participants of EG, when compared with CG [H(2) 19 = 12.16, p = .023].

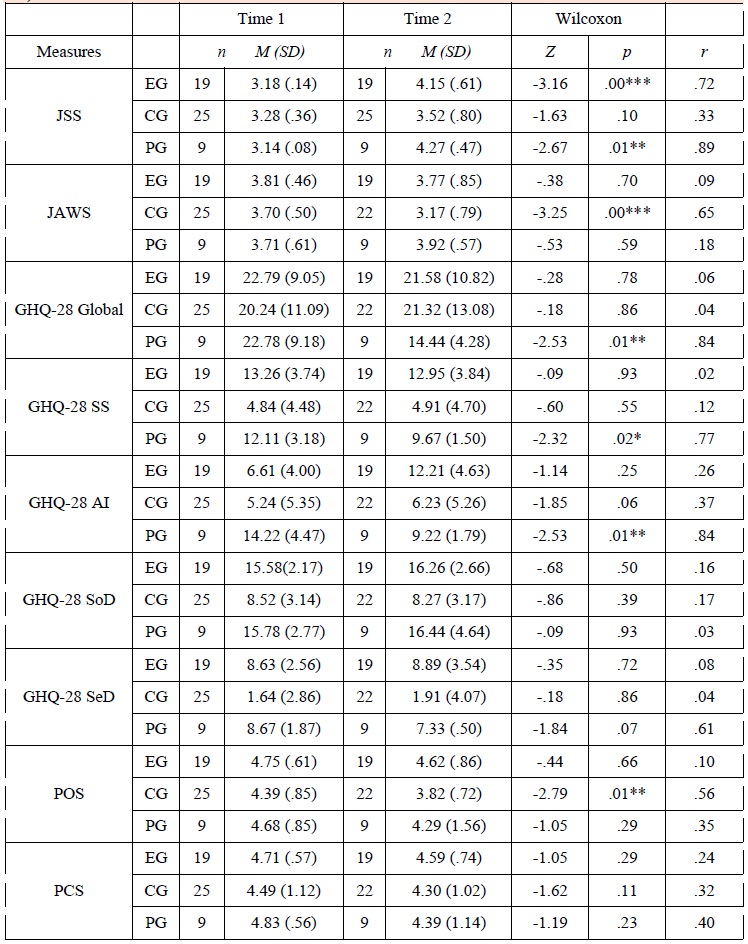

The results of paired comparisons are displayed in Table 3. Regarding the EG, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed a significant difference in JSS between the two assessments [z = -3.16, p < .00, r = -.72], with higher values at Time 2. This means that after the PSP, the EG presented higher job satisfaction. In relation to the CG, values showed significant differences in POS [z = -2.79, p <.01, r = .65], with lower values reported at Time 2, meaning that the CG participants seemed to decrease their perceived organizational support. Considering the PG, Wilcoxon signed-rank test values showed significant differences in JSS [z = -2.67, p <.01, r =.89], GHQ-28 Global [z = -2.53, p <.01, r = .84], GHQ-28 SS [z = -2.32, p <.05, r = .77] and GHQ-28 AI [z = -2.53, p<.01, r = .84], with all variables showing higher values at Time 2, which means an improvement on the assessed variables after the PSP. We found a large effect size for the majority of these variables (see Cohen, 1988, 1992).

Table 2 Results of comparison of EG (n = 19), CG (n = 25) and PG (n = 9) at Time 2

Note: JSS - Job Satisfaction Scale, JAWS - Job-related Affective Well-being Scale, GHQ-28 Global - General Health Questionnaire - 28, GHQ-28 SS- General Health Questionnaire - 28 Somatic Symptoms, GHQ-28 AI - General Health Questionnaire - 28 Anxiety/Insomnia, GHQ-28 SoD- General Health Questionnaire - 28 Social Dysfunction, GHQ-28 SeD - General Health Questionnaire - 28 Severe Depression, POS - Perceived Organizational Support, PCS - Perceived Colleagues Support

*p<.05, ** p<.01, ***p<.000

Table 3 Scores of measures before and after PSP on paired samples for EG (n = 19), CG (n = 25) and PG (n = 9)

Note: JSS - Job Satisfaction Scale, JAWS - Job-related Affective Well-being Scale, GHQ-28 Global - General Health Questionnaire - 28, GHQ-28 SS- General Health Questionnaire - 28 Somatic Symptoms, GHQ-28 AI - General Health Questionnaire - 28 Anxiety/Insomnia, GHQ-28 SoD- General Health Questionnaire - 28 Social Dysfunction, GHQ-28 SeD - General Health Questionnaire - 28 Severe Depression, POS - Perceived Organizational Support, PCS - Perceived Colleagues Support. *p<.05, ** p<.01, ***p<.000

Discussion

This study assessed the effects of a peer support intervention on job satisfaction, well-being, general health and perceived support among Portuguese Red Cross ambulance personnel. We found significant differences between groups after the PSP, with both experimental and peer support providers groups showing better results. As we hypothesized, we found better levels of job satisfaction and job-related affective well-being among ambulance personnel who participated in the PSP. Considering job satisfaction as an indicator of occupational mental health (Parks & Steelman, 2008) and knowing its influence in efficiency, productivity, absenteeism, intention to quit, and an employee’s overall well-being, our results highlighted the potential benefits that a programme like this has for an organization in this field of work. Furthermore, our results show that the PSP seems to improve perceived organizational support among ambulance personnel, specifically for those who received support. This may be explained by how much employees believe that the organization values their contribution and cares about their personal well-being (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). However, the results did not show significant differences regarding perceived colleagues’ support. We argue this may be explained by the previous level of perceived colleagues’ support, since this seemed to be a very cohesive team, perhaps due to the long amount of time these professionals had been working together, as found in a previous study (Oliveira et al., 2019). These ambulance personnel considered that talking with colleagues after occurrences is a common practice, and even before the programme implementation, ambulance personnel viewed their colleagues as supportive people on whom they can count.

Conversely to our hypothesis and to what is indicated by the most recent general health and psychological well-being literature (Solomon, 2004), the results of this PSP did not show similar benefits on this dimension among the experimental and peer support providers groups. We may explain these results by the short timeframe for the implementation, which may have resulted in a reduced number of peer activations to be able to detect significant results. Moreover, we must consider that these groups may have had a lower exposure to the emergency events, and a lower occurrence of critical events, and consequently, a lower need for peer activations. However, our results show that, at post-test, the peer support providers group reported better values on general health and psychological well-being, anxiety/insomnia and somatic symptoms. These results are congruent with some of the previous research that reported improvements in health and well-being (Pfeiffer et al., 2011; Repper et al., 2013), after peer support interventions, also for those who provide support (Davidson et al., 2012). Nonetheless, it is important to notice these improvements may be due to their sense of competence and efficacy, considering the monitoring period and the topics covered during the initial training, such as stress reactions, coping strategies and self-care recommendations. This leads us to hypothesize the potential benefit of extending the initial training to all participants, in accordance with what non-peer ambulance personnel mentioned in a focus group carried out after the PSP (Oliveira et al., 2019).

Although this study points to the positive effects of a peer support intervention programme for ambulance personnel, some limitations must be acknowledged. We were unable to control some variables (e.g., number and type of events), due to the unpredictability of their occurrence. This is a non-randomized quasi-experimental study employing a design, which does not control for all factors that may influence the inner validity of the experiment. Since we only collected data at two time periods, we believe additional assessment times can add value. Moreover, the small sample size, as well as the fact that participants were ambulance personnel only from the northern region of Portugal, may limit the generalization of these results to other ambulance personnel groups. Future studies should include a larger sample size, so as to use more robust statistical tests and to explore the effect of PSP within-subjects. Another limitation is the single use of self-report measures that could lead to response biases, through an acquiescence style and social desirability. We argue that including qualitative methodology can give sustained information, even with a small sample size. Therefore, although the results of this study seem promising, they must be read with caution, and more research is needed to further explore them.

It is worth noting that, more than benefiting individuals per se, peer support programmes can bring added value to organizations. On the one hand, this is a good cost saving approach and a way to conduct effective human resource management. One the other hand, it could foster a supportive work environment (Curling & Simmons, 2010), which, in turn, contributes to a better-quality service provided to the population served by these professionals.