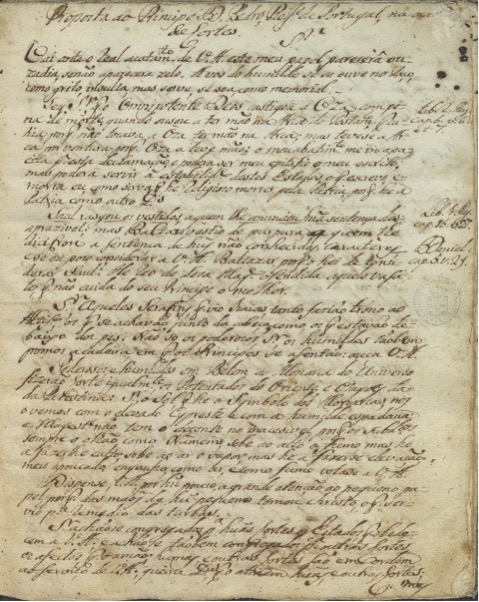

Illustration 1 Papel de Padre António Vieira. Source: Biblioteca da Academia das Ciências, https://biblioteca.acad-ciencias.pt/pacweb/files/mv019.pdf

The publication in 2014 of the twenty-volume complete works of Father António Vieira (1608-1697) brought the Jesuit’s apocryphal writings to a broader readership.2 One of these works is a long undated tract held at the library of Lisbon’s Academy of Sciences under the title: “Paper on the Parliament made by the Prince and Regent Dom Pedro, who afterwards was King of Portugal. Its author, Father António Vieira of the Society ENT#091;of JesusENT#093;.”3 Whereas this manuscript (hereafter called “Vieira’s Paper” for the sake of brevity) is probably not autographical, according to the information appended to this document, it was given to the erudite antiquarian, the Franciscan Friar Vicente Salgado (1732-1802), by the intendent of Lisbon’s maritime port Ribeira das Naus, Fernando de Lavre, one hundred years after Vieira’s death.4

Modern editors of this document have expressed skepticism about Vieira’s authorship, partly because a large part of the work does not reflect the Jesuit’s well-known views on Jews and New Christians.5 Whereas Vieira was a fervent advocate of the converso or New Christian group, even earning his current designation as a philosemite by calling for the professing Jews’ return to Portugal in the1640s (Novinsky, 1992; Novinsky, 2021; Niskier, 2004; Schwarz, 2003; Schwarz, 2008), this document echoes fierce anti-Jewish and anti-converso accusations and stereotypes. Without being able to definitively prove the authorship of this writing, I suggest that both contents and form fully correspond to the Jesuit’s views.

“Vieira’s Paper” was addressed to D. Pedro II (1648-1706) by the then regent of his elderly brother, King Afonso VI (1643-83), after his dismissal from the throne by a coup d’état in November 1667. Written from the perspective of a “humble voice” that prompted an “outcry of anger” in the form of an “explanatory memorial” (254), this work shows strong affinities with Vieira’s political writings addressed to King John IV (1604-56), his wife D. Luísa de Gusmão (1613-66), and their son, Pedro. Moreover, it also bears the rhetorical and stylistic imprint of his acclaimed sermons (Cantel 1959; Saraiva 1996; Mendes 1989). In this article I argue that “Vieira’s Paper” sheds light on the way the Jesuit faced one of the worst moments in the history of the New Christian phenomenon in Portugal when politics and anti-converso feelings became intertwined. Rhetoric and political messianism appear in this manuscript as tools to transform hatred of New Christians into empathy and support.

Vieira attained an influential position at Portugal’s court in the 1640s as confident of John IV, diplomatic emissary and royal preacher. The Jesuit saw in the dynasty of Bragança, newly restored from the Spanish Habsburgs, the beginning of a salvific era announced by the Portuguese prophet Gonçalo Anes Bandarra (1500-1556). In 1656, John IV died, and Vieira, by then preaching in the forests of Brazil, informed his widow that her husband would soon revive and fulfill Bandarra’s prophecies as the awaited “hidden” king (o Encoberto). When Vieira returned to Portugal at the end of 1661, however, he found the kingdom embroiled in turmoil. Most significant was the rift between the supporters of D. Luísa and those who sought to raise her son Afonso to the throne under the aegis of Luís de Vasconcelos e Sousa, 3rd Count of Castelo Melhor (1636-1720). The queen mother repeatedly attempted to postpone Afonso’s ascension to power on grounds of mental instability while she promoted her younger child, Pedro, as a better heir. Father Vieira was appointed by D. Luísa as Pedro’s personal confessor, and, according to Thomas M. Cohen, Vieira already alluded to his support for Pedro over Afonso in the sermon of Epiphany of 1662 (Cohen 1998: 233 n.3). That said, after the latter’s triumphant arrival in Lisbon as king in June 1662, Vieira, like other supporters of the Queen Mother, fell into disgrace and was exiled to the city of Porto. There, he faced a difficult inquisitorial prosecution which ran from July 1663 until December 1667 (Muhana 1999; Paiva 2011b). Early in 1668, our Jesuit departed in exile to Rome, where he obtained inquisitorial immunity from the pope and became engaged in the converso cause against the Portuguese Holy Office. Although the ascension of Pedro as prince regent might have meant the reinstatement of Vieira’s favor at court, it seems that the former was not overly receptive to the views of the latter. Despite moments of proximity and convergence, the relationship between the two was antagonistic (Azevedo 1918-1920, 2: 95-218; Vainfas 2011: 220-254; Lourenço 2010: 172, 279-81). Nonetheless, as Vieira’s 1689 “Apologetical Discourse” (Discurso Apologético), among other works, attests, the Jesuit continued to perceive Pedro II and his heirs as upholding the messianic hopes that he had invested in the person of John IV (Vieira 2014e: 249-306).6 As we shall see, “Vieira’s Paper,” which interweaves critique, optimism, and advice, expresses precisely these sorts of ambivalence.

The author of “Vieira’s Paper” begins by stating that he is aware of the temerity of intervening in matters of state, recalling that the biblical Uzzah was struck dead for touching the ark of the covenant despite his laudatory intentions (2 Samuel 6:6-7). He goes on to parallel his own situation with those of the prophets Samuel and Daniel, who had the difficult task of informing Saul and Belshazzar, respectively, that their reigns would soon end. In this initial captatio benevolentiae, the author expresses his hope that Pedro will follow the latter example rather than the former: while Samuel, as the bearer of this difficult news, became the object of Saul’s ire (1 Samuel 15:27), Daniel was richly rewarded by the Babylonian monarch (Daniel 5:29).

The rationale behind this behavior was the perception of political duty as compliance to the sovereign, which nevertheless entails civic responsibility: “a criminal of high treason is a subject who does not look after the best of his prince” (Vieira 2014c: 254). This principle especially applies in the case of “subjects” like Samuel and Daniel, who were endowed with particular wisdom and vision. In this self-fashioning address, the author of “Vieira’s Paper” is a simple subject whose task is nevertheless akin to that of the ancient prophets. Moreover, the Portuguese monarchs, in his view, are comparable to the biblical kings of Israel. Consequently, he claims, Portugal’s parliament or Cortes convoked by the prince regent does not correspond to the biblical character of its monarchy. Later in the treatise, he will elaborate on this claim, arguing that in earthly and political matters a Christian prince has absolute power over his subjects, although in spiritual and ecclesiastical issues he is bound by the authority of God’s earthly representative, the pope. Parliaments, for our author, violate the absolute nature of monarchy by limiting the power of the ruler, and in the case of the Cortes they also blur Christ’s fundamental division between the domains of God and Caesar (Matthew 22:21), which were given into the hands of Portugal’s secular ruler and the Roman pontiff (Vieira 2014c: 302-311, 331-332, 337-347). Additionally, he argues that parliaments are driven by power: fear of it, on the one hand, or abuse of it, on the other. Only spontaneous initiatives of subjects who genuinely care about the sovereign and the kingdom deserve the description “parliaments of love” (Cortes de amor). On the one hand, our author was elaborating on the widespread metaphorical political principle that allegiance between the prince and his subjects should be grounded on “love” (Gil Pujol, 2016). On the other hand, Cortes de amor also played on the concept of “court”: broadly understood as the space where the prince lived and interacted with his subjects. According to António Manuel Hespanha, the early modern court was a privileged arena to obtain concessions from the sovereign based on grace, thus contouring established norms and rigid criteria of justice (Hespanha 1993: 177-202). In other words, the author of “Vieira’s Paper” joined those who contested the legitimacy of parliaments by addressing Pedro in a more informal way of loving the prince in order to obtain his spontaneous loving grace. In this regard, the decision of the King of France, Louis XI (1423-1483), to outlaw parliamentary meetings as crimes of lèse-majesté is instructive. Accordingly, this harsh measure proved beneficial to France in the long run as it led to a tradition of avoiding the convocation of the three estates by subsequent monarchs. In contrast, the author presents the case of England, whose powerful parliament, he contends, was responsible for the calamitous civil wars of 1642-1651 (Vieira 2014c: 331).

These attacks against the Cortes merit discussion. On the one hand, by arguing that it is impossible to institutionalize a “parliament of love,” “Vieira’s Paper” seeks to undermine one of the main justifications for early modern Portuguese parliamentarism: as the best occasion for subjects and princes to express “mutual love” (Cardim 1998: 76-84). On the other hand, it implicitly questions the role of the Cortes at that moment of political instability: “not only for taxes, but also because now it became a growing concern to safeguard the crown from more than a probable crisis of succession” (Xavier and Cardim 2006: 101). On January 27, 1668, Pedro was hailed as prince regent by the Cortes, and on January 20, 1673, he officially convoked the Cortes to pronounce an oath of allegiance to his daughter, the princess Isabel Luísa Josefa (1669-1690). However, in these parliamentary gatherings and in the Cortes of 1679-80, the prince regent was seeking approval for the controversial dismissal of Afonso VI and his own recognition as Portugal’s ruler. Like in Vieira’s writings, the author of “Vieira’s Paper” questioned the legitimating function of the Cortes (Cardim 1998: 96, 112-114, Xavier and Cardim 2006: 203-214).

For our purposes, it is important to remember that Portugal’s Cortes, and particularly the ecclesiastical and third estates, traditionally held an anti-converso bias. They saw the New Christian “men of the nation” (homens da nação), as they were known, as an internal threat or a de facto “estate within the estates” rather than as mostly sincere Catholics and useful state-builders, as Vieira and other pro-converso elements claimed (Stuczynski 2011; Stuczynski 2019a). Moreover, inquisitorial persecution against the conversos, consistently supported by the ecclesiastical order, was envisioned by the third estate (“the people,” o povo) as a tangible expression of Portugal’s catholicity (Marcocci 2004: 337-354; Paiva 2011a: 213-260). In letters sent from Rome to the courtier and diplomat Duarte Ribeiro de Macedo (1618-1680), Vieira lamented that the Holy Office used parliamentary gatherings for their own purposes (Vieira 2014b: 385, 387, 431, 436). At the same time, the money and collective “pardon taxes” (fintas do perdão), which were periodically gathered by the New Christian group in exchange for inquisitorial amnesties and/or softer measures against converso exclusion (broadly called “general pardons”) as well as the economic contributions that the richest among the converso “men of the nation” (Boyajian 1979; Stuczynski 2007) were perceived by members of the third estate as a way of undermining their influence at the Cortes through taxation and political support.

During Pedro’s regency, the issue of his own legitimacy-threatened by actual or potential supporters of Afonso VI-taxation and the New Christian problem became tightly interwoven. Mostly for “reason of state” considerations, the prince regent was ready to moderate converso exclusion and appease inquisitorial persecution, to the point of almost conceding them the right of obtaining from the pope a general pardon, in exchange for the re-establishment of the short-lived company of commerce in India with New Christian capital and/or the offering of large sums of money to reinvigorate Portugal’s expansion in the East (Silva 1974; Disney 1979). Yet the prince regent relied heavily on the support of the Cortes in those years of political instability (Xavier 1998). This dilemma partly explains Pedro’s zigzagging from the moment he ascended to power until the sessions of the Cortes of May 24, 1674, when he finally opted, not without hesitation, to adopt a sustained anti-New Christian agenda (Azevedo 1989: 288-305; Xavier and Cardim 2006: 233-240, 258-261).7 In my view, “Vieira’s Paper” was probably written close to this turning point.8

As noted, “Vieira’s Paper” endorses French anti-parliamentarian attitudes. During the seventeenth century, the French governmental model was attractive for many pro-converso thinkers and writers, because it opposed centrifugal forces such as an autonomous Inquisition or a powerful parliament (Stuczynski, 2019 b). That said, “Vieira’s Paper” does not fully accept the Gallican model of politics and confessionalization. As in Vieira’s writings, “Vieira’s Paper” supports an “upgraded” Inquisition after the Roman model and upholds the views of the Jesuit cardinal Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621), who conferred to the pope the authority to intervene indirectly in secular matters (potestas papalis indirecta) when these touched upon spiritual issues (Bellarmine, 2012). As we shall see, for ideological and practical reasons, Father Vieira and “Vieira’s Paper” saw in the indirect intervention of the pope a legitimate and indispensable means to disentangle the knotty New Christian problem and Pedro’s dependence on the Cortes.

“Vieira’s Paper” is divided into three main sections. The first (Vieira 2014c: 256-265) aims to show that the Portuguese were destined by God to be his second “chosen people” after the election of the Jews. The author claims that the history of the Portuguese was analogous to that of the ancient Hebrews and biblical Jews (Vieira 2014c: 260-262). Thus, King Afonso Henriques (r. 1139-85) and his son Sancho I (r. 1185-1211) mirrored Moses and Joshua by relentlessly fighting idolatry before and after conquering their “promised land” of Portugal (Vieira 2014c: 262). Like biblical Judeans, Portuguese also suffered a sort of exile, when the foreign Spanish Habsburgs kings ruled over their motherland for sixty years (1580-1640) (Vieira 2014c: 262-265). Moreover, just as God revealed his election to the sons of Israel in the “written law” (lei escrita), in times of the Christian “law of grace” (lei da graça), Portugal was chosen to be a “peculiar kingdom of the Lord” after the miraculous revelation at Ourique. The so-called “miracle of Ourique” (or “oath of Ourique”), which is quoted in extenso in our manuscript (Vieira, 2014 c: 256-8), is the account of Jesus’ appearance to the founder of Portugal’s monarchy, Afonso Henriques, during the Battle of Ourique in 1139 against the Almoravids. Accordingly, Christ assigned to Portugal and its first king a sacred mission: “I am the founder and destroyer of kingdoms and empires, and I desire in you and in your descendants to found for myself a kingdom, by which means my name will be known in far-off nations” (Brandão 1632: 120; Buescu 1987). As in the prophetical writings of Vieira, the “miracle of Ourique” was considered a covenant (pacto) through which God conferred to the Portuguese the task of spreading Christianity throughout the world (Cantel 1950: 65-84; Azevedo e Silva 2008). This episode attained a sort of canonical status following its depiction by the royal chronicler Duarte Galvão (1440-1517), who cherished millenarian expectations (Aubin, 1996). Particularly after the dynastical “restoration” of Portugal’s throne from the Spanish Habsburgs on December 1, 1640, this myth-along with the lyric prophecies of Bandarra-became a foundational text of the variegated and evolving forms of Portuguese political messianism. (Lipiner 1996; Franco 2000; Gandra 2002; Bethencourt 2015).

Still, correlations and parallelisms between Hebrews or Jews and the Portuguese did not necessarily entail philosemitism. At least in the early modern Iberian world, these correspondences often exacerbated Jewish hatred (Kaplan 1988; Jordán 2003; Stuczynski 2008; Stuczynski 2012). Interpreted in a typological way, God’s distinction of the Portuguese not only was a new election; it was also understood as an upgraded one. In many respects, this was an extension of Christian theological supersessionism vis-à-vis Judaism to the ethnic and national political spheres, implying more than assuming that the election of the Catholic Portuguese transformed professing Jews into fossilized remnants of a glorious bygone era (Cohen 1999). Since God’s enhanced election was built upon the previous one, this view often propagated quasi-gnostic-Marcionite tenets. Thus, if the task of biblical Hebrews was to obey God and fight against the idolatrous peoples in Canaan, the mission of the Portuguese was to evangelize non-Christian Gentiles around the world and suppress “idolatrous Judaism” in the kingdom (Vieira 2014c: 256). In this section of the treatise, Jews and New Christians are depicted as the main obstacles to the fulfillment of Portugal’s sacred destiny revealed in Ourique. Accordingly, every time that Portuguese monarchs protected Jews and conversos (e.g., by admitting expelled Jews from Castile or enabling New Christians to marry Old Christians), the anger of God was aroused. Consequently, the kings João II (1455-9145) and Manuel I (1469-1521), who gave shelter to the expelled Spanish Jews in 1492, were punished by the premature death of their beloved heirs (i.e., the Infante Afonso, who died in an equestrian accident in 1491 and Miguel, the hereditary prince of Portugal and Spain, who passed away at the age of two). In the same manner, conversos’ promiscuity with Old Christians was divinely chastised by the usurpation of the Portuguese throne by Philip II of Spain (1527-98). Accordingly, this event mirrored the episode of Eglon, king of Moab, as related in the Book of Judges: “Again the Israelites did evil in the eyes of the Lord, and because they did this evil the Lord gave Eglon king of Moab power over Israel … ENT#091;tENT#093;he Israelites were subject to Eglon king of Moab for eighteen years” (Judges 3:12-14).

Our author also specifies that God is always ready to forgive the faults of his cherished peoples, accepting expressions of repentance and assisting them in their tribulations. Hence, just as God sent Deborah to liberate the Israelites from foreign oppressors and Gideon to uproot idolatry among them (Judges 4), the Portuguese received their own Deborah in the person of Queen D. Luísa de Gusmão-who played a central role in the dynastical restitution of the throne-and a new Gideon-none other than Pedro-whose main task was to extirpate Judaism (extirpação do Judaísmo) through a “law of extermination” (lei do extermínio) and the creation of a special council (Junta) to implement the law (Vieira 2014c: 263-265).

In three specific ways, “Vieira’s Paper” resembles other anti-converso discourses of its time, such as sermons, advisory essays (memoriales), and declarations pronounced by Portugal’s estates at the Cortes )Stuczynski 2007; Marques 1988; Marques 2010; Paiva 2010: 213-260; Soyer 2014: 96-97). First, such writings made extensive use of examples taken from history in order to show that God stood against the New Christian cause, as demonstrated by the outcome of specific historical events. Since God displays his divine providence to reveal his will, it is unsurprising that these examples were often taken from the Bible. Such references aimed to emphasize the holy character of the conflict between the Old and the New Christian populations, simultaneously perceived as a clash of civilizations and almost a cosmological rift between the forces of good and evil. In Carl Schmitt’s theological-political terms of politics, conversos were depicted by the initial part of “Vieira’s paper” as the second of the binary pair: friend/enemy (Schmitt 1996).9

The author of “Vieira’s Paper” presents D. Pedro’s anti-converso measures without discussing his abovementioned moments of hesitation or favor on behalf of the New Christians. For this reason, the Extermination Law and the gathering of a special Junta appear in our document as if they emerged from a single decision taken at the Cortes. The facts, however, were different. During the Cortes of 1668, the third estate already asked the new ruler to forbid New Christians honorable charges and offices, to outlaw marriages with Old Christians, and to expel from the kingdom those converso families who were convicted by the Inquisition as heretics (Azevedo 1989: 289).10 These requirements were considered by Pedro only after the affair of Odivelas, when New Christians were accused of desecrating hosts and other objects of cult in the Church of Odivelas during the night of May 10-11, 1671 (Paixão, 1938-1939, 2:120-5; Hanson, 1981: 90-107; Martins, 2002).

The episode of Odivelas surpassed previous outbursts of converso hatred, such as a similar episode of a host desecration at the Church of Santa Engrácia in 1630 (Stuczynski, 2022), in at least one respect. Rather than being dragged into the affair by the Inquisition and popular pressure, this time Portugal’s Cortes, members of the government, and the prince regent led a campaign of anti-converso retaliation. Thus, already in June 1671, Pedro was ready to adopt suggestions made by the Cortes of 1668 and members of his government and announced the expulsion of convicted New Christians and their families 11. This decree was the Law of Extermination of June 22, 1671, referred to by “Vieira’s Paper.” In July and August of that year, the prince regent issued additional laws, also recommended by the parliament and supported by Pedro’s political entourage, which reinforced converso exclusion from official charges and banned lawyers and physicians who were condemned by the Holy Office (Paixão 1938-1939, 3: 5-6; Andrade e Silva 1856, 8 : 191-192). In a vitriolic tract published in August 1671, Pedro’s secretary of state, Roque Monteiro Paim (1643-1706), explained the necessity of fully enforcing the “extermination” of the New Christians even before knowing the identity of the author of Odivela’s profanation. For, everybody presumed the effects of New Christian “infected blood,” which entailed a natural tendency to commit sacrileges like this. Although in the dedicatory introduction, the chaplain of the Portuguese ambassador in Madrid, Francisco Paez Ferreira, argued that Paim was just paraphrasing Pedro’s decree of June 22, and Bruno Feitler suggested that this tract could be a probable source of it, the later publication of the booklet was probably meant to be an admonition to a hesitant ruler to apply all the anti-converso measures required towards an “extirpation” of Judaism from the kingdom (Paim 1671: 1v; Feitler 2015: 61-65, 79).

Note that the concepts of “extirpation” and “extermination” were primarily understood as eradication of any form of Jewish heresy from Portugal because “only” New Christians convicted de vehementi by the Holy Office with their families (including children and grandchildren) were to be expelled.12 At the same time, the rest of the measures (i.e., the prohibition of marriages with Old Christians, the exclusion from offices, titles of nobility, and other honors, denial of entry to universities, and inability to entail estates or morgadios in their families), were collectively and retroactively applied to the entire New Christian “nação.”

Without necessarily using the word “extermination,” already in the 1620s voices were increasingly heard calling for implementing an expulsion of Portugal’s convicted Judaizers, as well as the reinforcement of “purity of blood” criteria, as parallel means to solve the persistent New Christian problem (Mattos 1622; Mattos 1625; Areda 1625: 8r-16v). For this purpose, an assembly of bishops, theologians, and other influential churchmen was reunited in Tomar in 1629 (Cohen 2003; Figueirôa-Rêgo 2011: 174-184). Vicente da Costa Mattos’ suggestions, made in his popular “Breve discurso contra a heretica perfidia do judaismo” (first published in 1622), to expel Judaizers because “a little Jewish blood is enough to destroy the world,” were published again in 1668 (Mattos 1668; Orfali 2001). But this did not mean that the anti-converso argumentation was the same. On the one hand, the concept of extermination became ubiquitous during Pedro’s reign, meaning a decanted combination between theological anti-Judaism and racial anti-Semitism. On the other hand, whereas the radical anti-converso voices of the 1620s were heralded by churchmen, inquisitors, and individuals (Yerushalmi 1982; Riandière La-Roche 1983), much against the opinion of kings and their counselors, now such an approach was adopted by the political class. Such shift in the discursive regimes of the 1660s and 1670s enabled the Duke of Aveiro to infer from the Odivelas affair these satirical comments:

Men of the nation have two types ENT#091;castasENT#093; of blood: one that flows through the veins; other from the bags ENT#091;bolçasENT#093;. From the veins, all of them are Jews ENT#091;JudeusENT#093;; from the bags, many of them are noblemen ENT#091;fidalgosENT#093;. From the side of being Jews, all of them are despised; and from the side of being noblemen, they are loved by many.13

Unsurprisingly, Vieira was a leading voice against the Extermination Law, arguing that it was approved well before knowing the real author of the crime of Odivelas: a simple Old Christian thief called António Ferreira who only had some diluted converso blood in his veins. He also denounced the law for being unfair, unmerciful, and therefore un-Christian (Vieira 2014c: 82-106). Pedro was also dissuaded by his confessor, the Jesuit Manuel Fernandes (1614-1693) (Camarão 2017: 156-165). Thus, in order to obtain additional support for this controversial juridical measure, Pedro first submitted it to the advice of a council (Junta grande) of churchmen, theologians, jurists, and counselors, which was intended “to punish, extinguish and diminish by any means possible, those of that nation who live in this kingdom and in the conquests, seeming more lenient the punishments given by the Holy Office than what they deserved to receive by reason and justice,”14 and then, he addressed it to the Cortes (Azevedo 1989: 297). Both events are referred in our tract.

The first section of “Vieira’s Paper” ends with a set of learned quotations illustrating the difficulty a simple author faces when telling his powerful addressee a disturbing truth (Vieira 2014c: 265). Thus, the reader of this manuscript is left with the impression that the juridical measures taken by Pedro at the Cortes to destroy Judaism embarrassed the very legislator who had advocated for their implementation.

The enigmatic corollary of the first part is elucidated throughout the second section of the manuscript (Vieira 2014c: 265-311). The first half (Vieira 2014c: 265-80) is an answer to those who questioned the efficacy of Pedro’s anti-converso measures by detailing the damage they could cause to Portugal’s demography and economy. Our author answered these objections-which stemmed from mercantilist assumptions and were central in pro-converso discourses of the seventeenth century, including Vieira’s letters to King John IV (Vieira 2014c: 31-46, 49-81)-by claiming that neither a demographic surplus nor the smoothing effect of money were guarantees of social stability and welfare, as seen in the biblical destruction of the wealthy and populous Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 18-19). More recent historical events, he adds, confirm that war against idolaters, apostates, and infidels is necessary to purge a country from its evils and rebuild it again with the help of God and a country’s pious subjects. Portugal’s successful medieval wars of Reconquista against Islam were a telling example of this. But even from a non-providential perspective, a numerous religious minority always entails a potential threat. That is why King Ferdinand II (1452-1516) expelled Spain’s large Jewish population in 1492 and Philip III (1578-1621) did the same with the morisco masses between 1609 and 1614.15 Even a few heretics could be enough to arouse seditions and civil wars, as evidenced by the Hussites in Bohemia and the Huguenots in France. Moreover, “four or five Lutherans broke down the Church in Germany, and a few more Calvinists corrupted the religion in England, Holland, Dacia, Norway and in the rest of the countries of the North” (Vieira 2014c: 267).16

Concerning economy, “Vieira’s Paper” combines converso hatred with a widespread critique against the deceptive power of riches (Vilches 2010). Most likely, the author is alluding to the noxious effects purportedly caused by New Christian money offered as “services” in exchange for general pardons and other indulgences, when he declared: “even for good deeds, this money doesn’t help at all: if it is offered to the church and it is accepted, it causes schism; and if it is given to the prince, it serves him to harm” (Vieira 2014c: 269). Wealth easily corrupts morals and faith. Thus, in the same way that the riches of Gentiles who lived in biblical Palestine provoked idolatry in their Hebrew neighbors, the wealth of those “Hebrews” who now live in Portugal provoke the propagation of Jewish heresy among Christians: “This happens, my Lord, and this is what we see every day, that there are a few places in our Portugal where there are not polluted (impuros) people. I do not mean everybody, but many of its inhabitants; for actually there are so many synagogues as churches, and with the same retinue is worshiped the calf and the lamb” (Vieira 2014c: 270).

The fight of Pedro against powerful Judaizers is compared to Judas Maccabeus’ strife against the mighty idolatrous forces of Seron, governor of Syria (1 Maccabees 3) (Vieira 2014c: 270-272). This analogy is followed by a list of crimes purportedly committed by New Christians in Portugal (i.e. sacrileges, blasphemies, theft of hosts and sacred images, mockery of religion, and the crucifixion of innocent people), which echoes the recent affair of Odivelas (Vieira 2014c: 272-273).

In light of all this evidence, the author must address this question: How could the harm threatened by New Christians be stopped, considering the fact that none of the existing means, including the Inquisition and the exclusory laws of purity of blood, suppressed it? Members of the Cortes, the Junta, and Pedro’s advisors like Paim answered: through the enforcement of the Extermination Law. In its answer, “Vieira’s Paper” even rejects Pedro’s decree, arguing that the way exiled conversos were welcomed by “the nations of the north” (as nações do Norte) proves that banishment was for them a relief (descanso) rather than a punishment. Therefore, the author calls for reducing converso Judaizers to slavery. If it is true that after baptism, theological serfdom of Jews is definitively abrogated and no secular authority can intervene by its own initiative in matters pertaining to the Church, such as the Inquisition. At the same time, a Catholic sovereign can reinforce decisions taken by the Church, such as declaring any conversos, along with their families, slaves if convicted by the Holy Office. Being aware that these measures countervail aspects of canon law and the lenient attitudes of leading theologians and churchmen (including Bernard of Clairvaux and Thomas Aquinas)-that even the most radical supporters of “extermination” did not seriously envisage slavery as a feasible means to solve the persisting converso problem-the author of “Vieira’s Paper” evokes the subjection of the Gibeonites by Joshua (Joshua 9:16-27) and compares it to the modern enslavement of black people (etíopes) by the Portuguese (Vieira 2014c: 274-279).17 Whereas in the latter’s case, serfdom was a means to obtain their spiritual salvation, the subjugation of the Gibeonites as “woodcutters and water carriers” was a deserved punishment for their deceptive behavior and a preventive means of any future attempt at treason. In other words, the enslavement of New Christians resembles the situation of the Gibeonites in constituting an emergency measure of state dictated by theological-political considerations. Our author finally claims that without such an extraordinary juridical measure, Portugal will shortly arrive at the situation of Sodom and Gomorrah before its destruction, when the number of their righteous citizens was less than ten (Genesis 18:16-33). On the one hand, “Vieira’s Paper” endorses apocalyptic overtones of those who wholeheartedly supported the Extermination Law, including the author of this anonymous poem: “If the Law is that of Moses, / According to what do they say ENT#091;i.e. the New ChristiansENT#093;, / And the sword of our God/ Do not slain heresies, / In days less than a few, / we shall all become Jews” (Paixão 1938-1939, 3: 61). On the other hand, the embarrassment of the author of “Vieira’s Paper” vis-à-vis Portugal’s ruler here appears as the result of the realization that Pedro’s anti-converso measures were not severe enough.

Surprisingly, the extant half of the second section (Vieira 2014c: 280-311) entails a dramatic shift: “ENT#091;butENT#093; now, my Lord, let us temper this declaration, so it would not seem that hate, instead of Catholic zeal, sharpened our pen.” Thus, after summarizing the damages purportedly caused by the New Christians, he announces:

Nevertheless (todavia), I will now argue (direi agora) that these punishments never happened, and will never happen in this kingdom because of the Jews (judeus): the men of this nation should not be expelled from the church, specifically because their ancestors killed Christ, but only if these men do not believe in Christ; and for this reason, those who believed and believe ENT#091;in ChristENT#093; deserve to stay within the Church, in spite of descending from those who killed ENT#091;ChristENT#093; (Vieira 2014c: 280).

It is worth noting the dialectical-scholastic character of this excerpt was typical of the juridical culture of the time (Hespanha and Cabral 2002). After extensively elaborating a justification and intensification of the anti-converso measures taken by the prince regent, the author now announced its antithesis. As in some of Vieira’s sermons, the sudden change is aimed to arouse surprise. Furthermore, the reductio ad absurdum of opinions held by the addressee, using hyperbole, is aimed at efficaciously dismantling them (Cantel 1959: 377-388, 422-425). In a letter addressed from Rome to his friend Rodrigo de Meneses at the height of the Odivelas affair, Vieira employed similar anti-Semitic overtones by calling conversos “Jews” and comparing them to excrement: “Shit, says St. Augustine, out of its place dirties the house, and put in its place fertilizes the field.” Accordingly, the noxious presence of New Christians in Portugal was nonetheless needed to enrich its imperial and evangelical endeavors: “Remove from Portugal the Jews, the sacrileges, the offence to God and keep in Portugal the merchants, the commerce, the opulence” (Vieira 2014b: 133; Chakravarti 2018: 297).18 In the case of “Vieira’s Paper,” by underscoring that the main reason for the anti-converso measures was heresy, its author could now easily argue that at the core of the New Christian problem is the question of religious sincerity and not matters of lineage, purity of blood, or ethnicity. Thus, if the New Christian phenomenon is fundamentally a religious issue, it can also be inferred that its ultimate solution should come from the pope, the Church’s supreme authority. At the same time, the words “now” and “nevertheless” indicate casuistry. As Carlo Ginzburg and other scholars have explained, casuistry is a sophisticated cognitive instrument or technique that approaches difficult choices which contemplate exceptions within norms (“exceptions include the norms, not the other way around”) (Ginzburg and Biasori 2019: XI). Ginzburg sought to rehabilitate this erstwhile widespread technique from discredit by influential thinkers, such as Blaise Pascal in his “The Provincial Letters” (1656-1657), who famously associated casuistry with “Jesuitical” sophistry and hypocrisy. In the case of “Vieira’s Paper,” the use of the word “nevertheless” ironically indicates that the author’s purported exception is the appropriate norm (Ginzburg 2018: 29). In other words, casuistry helps our author to counterargue that neither Pedro’s anti-converso legislation nor the instigations of the Cortes against the “men of the nation” are adequate or legitimate.

Following these new premises, the author of “Vieira’s Paper” declares himself unopposed to the punishment of heretical Judaizers. But he also calls for honor to be shown to the faithful New Christians. Furthermore, if the duty of a Christian prince is to support the Church, the prince regent should know that the traditional attitude of the Catholic church vis-à-vis converted Jews followed Paul’s ecclesiological principle, accordingly: “Anyone who believes in him will never be put to shame. For there is no difference between Jew and Gentile” (Romans 10:11-12). Moreover, as a pious Christian the prince regent must do everything he can to ensure that “good Catholics ENT#091;willENT#093;…come from the Hebrews” (Vieira 2014c: 280). In order to attain this goal, Portugal should avoid the collective abasement of the converso group. Rather, Castile ought to be lifted as an example, since there baptized Jews often received royal honors and many of them successfully intermarried with the most noble of the Old Christian families. The results were telling: “an ocular result of this good Catholic policy is the fidelity of them to the Church, because in a short time, and since no error was discovered among them, their blood went unnoticed” (Vieira 2014c: 281; cf. Vieira 2014d: 351). Paradoxically, when blood purity criteria were enforced (e.g., during Toledo’s anti-converso uprising of 1449), Castilian New Christians “began to commit errors of Judaism” (Vieira 2014c: 282).

Such a portrait of integrative Castile versus exclusionist Portugal was not fully accurate, nor it was new. Better known from the third chapter of Baruch Spinoza’s “Theologico-Political Treatise” (1670), this argument echoed an apology on behalf of the Portuguese “men of the nation” written in 1619 by the Spanish licenciado Martin González de Cellorigo (c. 1565?-1635?) (Stuczynski 2011; Yerushalmi 2014). According to the author of “Vieira’s Paper,” the Castilian model promotes social integration and offers conversos a powerful incentive to avoid heresy and embrace Christian faith. Similar policies, he adds, were enforced in France, Germany, and Italy (Vieira 2014c: 293). Note that contrary to Vieira’s letters addressed to King John IV in the 1640s, the author of “Vieira’s Paper” does not overemphasize the proverbial economic skills of the “men of the nation.” Perhaps, at the height of a process of stratification in Portuguese society, the choice of employing a rationale grounded on meritocracy and mercantilism would be a rhetorical mistake.19 No wonder, then, that our author opts to remind his audience of the potentially noble status of the conversos as a way of demonstrating that New Christians could be integrated into the different strata of society. Since ideas about nobility were strongly associated with Old Christian aristocracy and built upon an antagonistic rejection of the New Christian “stained blood,” “Vieira’s Paper,” like many other pro-converso apologies, has to deconstruct these widespread assumptions. In the first place, our author employs authoritative tracts, such as André Tiraqueau’s “De Nobilitate et Jure Primigeniorum” (1549), to demonstrate three different ways of becoming noble: “generous,” if given by God; “political,” when conferred by princes; and “acquired,” as a result of riches (Vieira 2014c: 282-283).20 New Christians, our author claims, could access nobility from all these avenues. Thus, considering that the members of the Hebrew nation were the offspring of God’s patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and of Jesus Christ the man, the Virgin Mary, and her parents, who “were very noble people of this nation,” he asks: “Whose nobility could be compared to the Hebrews?” (Vieira 2014c: 283). Our author also recalls the authoritative opinion of the Castilian jurist Juan de Arce de Otálora (c. 1515-1562), who stressed that New Christians could be ennobled by secular rulers (Arce de Otálora 1613: 197-210). In confirming this well-known fact, he adds that “acquired” nobility was not an obstacle for many New Christians.

“Vieira’s Paper” also responds to those who believe that the participation of the Jews in the crucifixion disqualified their offspring forever from honors.21 This contention is true, the author says, but only for professing Jews. By employing a series of hyperbolical questions, our author demonstrates that this could not be applied to Jews who embraced Christianity: Who will be able to say that St. Paul the Apostle retained a stain of infamy? Would it be reasonable to argue that such inherited shame could be imposed on the founders of the church, who were Jewish converts (“Dei ecclesia fundata est de Judaeis conversis”)? Should illustrious conversos and devout sons of Jews, like Pope Evaristus (c. 99-c. 107), Archbishop Julian of Toledo (642-690), or Pablo de Santamaría (c. 1350-1435) and his son Alonso de Cartagena (1384-1456)-both bishops of Burgos (285, 287)-be excluded from high ecclesiastical ranks and honors? Precisely, our author contends, Paul, the “Apostle to the Gentiles,” addressed his “Epistles to the Romans” against this mistake (Cf. Vieira 2014d: 192-195). In this and in other texts, Paul called Gentile Christ-believers to wholeheartedly welcome Jewish Christ-believers without despising them, to the point of feeling a need to recall his own Jewish roots (Acts 22:3; Romans 11:1; Philippians 3:5). Still following Paul, our author reminds his readers that Jews take part in the project of universal salvation of mankind which was revealed in Paul’s Romans 11, whenever they convert to Christianity and rejoin “their natural tree trunk” (Vieira 2014c: 285-287, 290).

“Vieira’s Paper” denounces the erroneous interpretation of Paul’s concept of the “neophyte” (Timothy 3:6) to justify converso exclusion from dignities and honors.22 A neophyte, our author notes, was an ephemeral juridical status of two years intended to give the freshly converted Christian time to adapt to his new life before applying for ecclesiastical ordination (Vieira 2014c: 288). In addition, this interpretation negates all those who compare the status of the New Christians to the juridical shame inherited by sons and grandsons of slaves. For, unlike the case of slavery, nobody can inherit Jewish stigma after becoming “new men” through baptism (e.g., 2 Corinthians 5:17). Even the juridical infamy transmitted by crimes of heresy disappear after two generations (Vieira 2014c: 291-293; cf. Bond 2014).

In one respect, “Vieira’s Paper” recalls António Ribeiro Sanches’s (1699-1783) proposal of 1748, which advocated for the abrogation of the categories of Old and New Christians by focusing on psychological aspects of converso exclusion (Sanches 1956; Saraiva 2001: 123-129). According to the author of “Vieira’s Paper,” whereas New Christians were collectively shamed for crimes committed by distant ancestors who lived in Second Temple’s Palestine (despite the fact that not all the Jews took part in the deicide), the participation of Gentiles in the crucifixion of Jesus and in the persecution of Christians throughout history and even in their present times (e.g., the persecution of Catholics by Protestants) did not prevent their progeny from immediately attaining honors once they converted to Catholicism. A sentiment of indignation was particularly vivid among the educated “men of the nation” who were numerous within the group (Vieira 2014c: 294-296). This widespread feeling was encapsulated by paraphrasing Aristotle’s principle of greatness of soul in the Nicomachean Ethics (book 4, chapter 3): “Honor is the highest good . . . and without honor, life is considered as terminated” (Vieira 2014c: 297).

Contrary to Ribeiro Sanches, however, the author of “Vieira’s Paper” does not call Pedro to immediately suppress the category of New Christians. It would suffice to treat the converso group as full-fledged Catholic subjects, and this would happen naturally in the same way that in some parts of Portugal descendants of the Jewish children baptized by King Manuel I in 1497 lived unmolested and without ever Judaizing because “they were always treated as Catholics” (Vieira 2014c: 293). In other words, the main means to suppress Judaism is to halt collective stigmatization. This, however, requires the abrogation of exclusionary laws impeding New Christians from attaining the same ranks and functions (e.g., judges and magistrates) as Old Christians. Being “members of the mystical composite of the Church” (membros do composto místico da Igreja), New Christians should be seen as part of a same collectivity (fazendo um todo) along with the Old Christians (Vieira 2014c: 296). Therefore, Portuguese society would attain this lauded “apostolic unity” through punishing persistent evildoers and rewarding its virtuous members: “My Lord, let those who will not apostatize become citizens (cidadãos), and slaves those who will relapse, and in a few years the name of New Christian will disappear from Portugal forever” (Vieira 2014c: 299). Note that the author of “Vieira’s Paper” employs a traditional pro-converso leitmotif: the Pauline idea that baptized Jews were part of a same “mystical body” with Gentile Christian believers (e.g., 1 Corinthians 12:12-27; Ephesians 4:3-5). Pro-converso writers had diverse perceptions concerning the precise contours of that “body” (since its original ecclesiological dimension was increasingly understood within secularized terms of “body politics”) and put a different emphasis on the issue of internal roles and hierarchies of the “organs” within the “body” (i.e. hierarchy of functions vs. parity vis-à-vis a common “head”). Still, all of them avoided obliterating its original Pauline connotations, precisely because Paul made the metaphor explicitly about how to integrate Jews and Gentiles in the same community of Christ believers (Stuczynski 2014a). In the case of “Vieira’s Paper,” the concept of a “mystical body” is perceived as the community of congregants whose bonds are created by a shared faith and participation in the sacraments, which then overflows into the social and political domains. Such a perception of Portuguese society is strongly sacramental and fully corresponds to what Alcir Pécora (2016) identified in Vieira’s sermons.

Approaching the end of the second part of the tract, the author of “Vieira’s Paper” returns to employ the apocalyptic overtones of the first section, to warn the prince regent yet again of the increasing influence of Judaism in Portugal: “either we make them Catholics, or they will make us Jews. If your highness will not ennoble them (fazer fidalgos), they will turn us into handworkers (mecânicos)” (Vieira,2014c: 299-300). The New Christian problem is still perceived by our author as an urgent matter. But this time, its resolution is radically opposed to what Pedro promoted with the support of the Cortes.

This way of symmetrically reversing the claims of the first half of the tract is apparent, among others, in the fact that our author again invokes measures taken in the past to “eradicate Judaism.” However, his purpose is now to demonstrate that the traditional use of inquisitorial persecution and other forms of coercion (“the practical remedies of the iron and the stake”) are not efficacious remedies to heal the prolonged afflictions suffered by the converso group. 23 Rather, he invites the prince regent to employ a therapeutic means he called the “music of franchise” (musica dos foros), inspired by the widespread metaphoric idea that the sweet sound of music heals melancholy and other forms of “evil spirit” (e.g., David playing the harp before Saul in 1 Samuel 16:14-23) and promotes harmony between subjects and their sovereign (Bouza Álvarez 2000). Thus, instead of supporting preachers who harshly condemn “Judaic errors” made by conversos before an audience of New and Old Christian congregants and increase estrangement, our author calls on Pedro to privilege sermons that demonstrate the inconsistencies of the rabbis with persuasive and tempered words in order to obtain the social integration of the converso group as full-fledged Catholics (Vieira 2014c: 300-301). This is precisely what Vieira intended to do in an uncompleted missionary and catechetical book, addressed to professing Jews and New Christians, which he called “Secret Counselor” (Conselheiro Secreto) (Vieira,2014a: 229, 334; Muhana 2021).

Our author also calls to apply that “music of franchise” to nullify a law instigated by the Cortes, which forbade the New Christians to seek assistance from the pope in matters related to the Inquisition. Let us remember that as the Extermination Law undermined much of the inquisitorial activity against the converso group, and because it shamed many noble families who were already stained with New Christian blood, the prince regent finally decided not to enforce it. 24 As a sort of compensation, in May 1672, the General-Inquisitor issued a decree stipulating that convicted Judaizers and their offspring would be forbidden to display public manifestations of social distinction (riding on horses, travel in coaches, wearing silk and jewels), obtain honorific charges and titles, or farm taxes for the crown. During the months of July and August, wealthy leading converso merchants were imprisoned by the Holy Office. Pedro was asked by New Christian leaders and pro-converso supporters like Vieira for the right to negotiate in Rome a general pardon for these and other “men of the nation” and obtain an eventual reform of Portugal’s biased Holy Office. In 1673, the prince regent was ready to accept these queries. To appease the protests of the anti-converso faction, Pedro also enabled the Inquisition to send their own representatives to Rome (Paiva, 2012). From January 1674, the Cortes begun to ask the prince regent to reject the conversos’ pretentions before the Holy See (Paixão 1938-1939, 3: 42, 49-50, 54-56, 60-70; Azevedo 1989: 293-295, 300-301; Marcocci and Paiva 2013: 202-203). 25 This initiative was finally accepted by Pedro on May 24. 26The reason invoked by the peoples’ representatives at the Cortes was that conversos’ money would incline Rome in their favor. This argument is labelled by our author as “a sacrilegious profanation” against the Vicar of Christ. The pope, he replies, is the “visible head of the Church” and therefore the sole “source of justice” inspired by God. How could his divine probity be questioned? “The pope and God constitute a same tribunal” because “the pope is a living God on earth” (Vieira 2014c: 303). Whereas in his previous argumentation the author of “Vieira’s Paper” responds to those who, one way or another, aimed to fulfil the spirit of the Extermination Law, at the core of this part of the tract is a defense of the inalienable right of Christian members of the “Hebrew nation” to apply to their supreme spiritual shepherd and the right of the Roman pontiff to modify or nullify any norm “when this law is harmful to the salvation of the Christian flock” (Vieira 2014c: 306). These arguments are summarized by Vieira in his “Catholic Disillusionment” (Desengano Católico) in response to the claims made of the bishop of Leiria that the prince regent was committed to safeguard the rights and privileges of the Portuguese Inquisition which were conceded by previous monarchs (Vieira 2014c: 111-114). 27 In other writings, the Jesuit notes that the committee of theologians, lawyers, churchmen, and inquisitors gathered by the prince regent supported the right of the New Christians to apply to the Holy See, without forgetting to mention their pecuniary offer to avoid the loss of India to Portugal’s enemies (Vieira 2014c: 186-189). Moreover, what at the beginning of the tract appears as the more relevant issue (i.e., Pedro’s Extermination Law) became a sort of prolegomenon to the most burning subject: the reform of the Inquisition.

Our author admits that the Holy Office was established with the approval of the pontiff and the college of cardinals. This tribunal, he acquiesces, would still play a fundamentally positive role in eradicating heresy in different Christian lands. What is at stake is not the existence of that institution. Rather, it is the pressing need to review the procedures employed by the Portuguese Holy Office against the “men of the nation” and eventually adjust them to the methods employed by the Roman Inquisition.28 Thus, he argues that the “anxious people” at the Cortes were wrongly offended by the supplications of the New Christians to the pope. By submitting their requests to the arbitration of the Holy See, they made an act of obedience to the head of the Church and a laudable demonstration of judicious piety, “because a hasty zeal sometimes provokes horrible crimes” (Vieira 2014c: 309). Probably, these words make reference to the way anti-converso zeal, heralded by the third estate in the Cortes, affected the Odivelas affair, the truncated Extermination Law, and the opposition to Inquisition reform.29 At the same time, the conclusion of the second part of the tract announces an intensification of the efforts made by all those who, like Vieira, asked the pope to put an end to the biased, rigorous, and unevangelical way of facing the New Christian problem in Portugal, now embodied by the Inquisition. Not much time after the probable composition of “Vieira’s Paper,” on October 3, 1674, Pope Clement X (1590-1676) suspended the Inquisition’s activities (Faria 2007; Marcocci and Paiva 2013: 201-209; Lloyd 2018).

The third and final section of “Vieira’s Paper” is a return to the initial premise: that the Portuguese people received divine election and must fulfill the covenant of Ourique. The prince regent is thus called to reassume this task through “navigation, trade and conquest in Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia and India” (Vieira 2014c: 311-349). Here, instead of arguing that Portugal’s election primarily meant an extermination of Judaism, it implies a focus on overseas expansion. Moreover, its author addresses a list of memorable actions made by each Portuguese monarch in which neither Jews nor conversos were a cause of sin. Thus, while the seizure of the throne by the Spanish Habsburgs is still understood as a divine punishment, it is now explained as a result of the loss at the Battle of Ksar El Kebir in 1578 by King Sebastian (1554-1578), because “he pretended, with Christian blood, to obtain lands for a Moor which belonged to another Moor.” Sebastian’s fatal error was to follow the North African policies of his grandfather, King John III, which diverted the Portuguese from their holy duty. Neither monarch understood that “the Almighty does not support endeavors made by Catholics, if they are not Catholic endeavors” (Vieira 2014c: 315). Although it never exhibited the same level of verbal vitriol, islamophobia now replaced antisemitism, since the enemy of Catholic Portugal became Islam instead of Judaism. As I have argued elsewhere, this shift was one of the main characteristics of late medieval and early modern Judeo-Christian affinities in Iberia. And it was apparent in writers and thinkers like Vieira, whose views were imbued with the millenarian tradition associated with Joachim da Fiore (c. 1135-1202) (Stuczynski 2019c).

Since Portuguese rulers were rewarded or punished by God according to their commitment to Ourique’s legacy, our author now encourages the prince regent “to sculpt his own actions against the wretched infidel,” meaning the Muslims. Once the prolonged dynastical conflict with Castile came to an end in 1668, it was time to return to Portugal’s crusade of expansion to the East. The author of “Vieira’s Paper” enthusiastically calls upon Pedro to restore the glorious beginnings of the Portuguese conquests in the Estado da Índia, invoking iconic heroes and infamous foes: “Bring again to the East the propitious omens of the Gamas, the Almeidas, the Albuquerques, the Castros, the Cunhas, the Cabrals; let the young noblemen (fidalgos) gird the first sword before the sight of arrogant Adil Khan (Hidalcão), the presumptuous Turk and the intrepid Persian” (Vieira 2014c: 316). As attested by the almost verbatim reference to King Manuel’s titles: “Lord of navigation, conquest and trade in Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia and India,” Pedro’s duty is to return to Manuel’s objectives of achieving a messianic empire (Thomaz 1990; Stuczynski 2013). This enterprise not only requires fighting against the “infamous Muhammad” (infame Mafoma) (Vieira 2014c: 317); it also entails a reprisal of missionary activities in the East, as foretold by Isaiah:

Woe to the land shadowing with wings, which is beyond the rivers of Ethiopia: That sendeth ambassadors by the sea, even in vessels of bulrushes upon the waters, saying, Go, ye swift messengers, to a nation scattered and peeled, to a people terrible from their beginning hitherto; a nation meted out and trodden down, whose land the rivers have spoiled (Isaiah 18:1-2).30

Accordingly, the military and spiritual dominion over India is not simply another step towards the achievement of Portugal’s vocation; it constitutes a dramatic qualitative leap. Supported by the Fourth Book of Esdras (especially chapter thirteen), “Vieira’s Paper” infers that the “nation” mentioned by Isaiah as living beyond Ethiopia somewhere in India are the ten lost tribes of Israel. No wonder that the same prophet said: “Do not be afraid, for I am with you; I will bring your children from the east and gather you from the west” (Isaiah 43:5). This must be a prophetic allusion to the Portuguese who “rule from over the last waves of the ENT#091;AtlanticENT#093; ocean to the eastern waters of the Indian sea, and from the last sands of the Tagus to the end of the universe (remate do universo).” In other words, the Portuguese are destined by God to discover, gather, and convert to Christianity the lost ten tribes of Israel. It was probably for this reason that “Portugal was the province through which by chance or mercy, almost all of the Hebrews crossed during almost all of the ages”: from the exiled Judeans by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (c. 605 B.C.-c. 562 B.C.) to those numerous Jews who arrived to Sefarad after the destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE by Titus and Vespasian to the more recent masses of Castilian and Aragonese Jews expelled in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs (Vieira 2014c: 318-323; Beaver 2013; García Arenal and Rodríguez Mediano 2015). Whereas in their journey many of them converted to Christianity and adopted Portugal as their homeland, these subsequent migrations were a sort of rehearsal for the final and most dramatic one: that of the lost ten tribes of Israel.

It is not my aim to trace the evolution of this enduring biblical myth (Ben-Dor Benite 2009; Volpato 2018). Suffice it to say that the eventual encounter with members of these tribes in a remote part of the world aroused messianic hopes and millenarian expectations among both early modern Jews and Christians. We know that for Vieira, the discovery, conversion to Christianity, and gathering of the lost ten tribes of Israel in Palestine, along with the rest of the Jews, was a crucial step towards the last and most supreme stage of human history, initially called by him the “Fifth Empire,” after the Book of Daniel, and then also depicted as “the reign of Christ on earth” (Valdez 2016; Valdez 2017). Fully corresponding to Vieira’s prophetic and messianic interpretations, “Vieira’s Paper” conveys the conviction that the renewal of the military and spiritual conquest of India by Pedro would hasten the salvation of humankind by the evangelization of non-Christian Gentiles and especially by the discovery of the ten lost tribes of Israel. As revealed in Paul’s Epistle to the Romans 11:25-26, after Jesus’s coming, “blindness in part is happened to Israel, until the fullness of the Gentiles be come in. And so all Israel shall be saved: as it is written, there shall come out of Sion the Deliverer, and shall turn away ungodliness from Jacob.” For Vieira, this implied that the process of salvation of Gentiles and Jews was simultaneously distinct and interrelated. On the one hand, the discovery of those lost sons of Jacob would be a sign of the final salvation of the entire Jewish people, understood by him as conversion to Christianity. On the other hand, it would be a most tangible sign that the salvation of the Gentiles (“the fullness of the Gentiles”) had already occurred (Cohen 2005; Stuczysnki 2021).

In “Vieira’s Paper,” these alternating Judeo-Gentile rhythms of salvation appear in an implicit way, prompting its author to call on his addressee to adopt a twofold policy: a proper evangelization of the Jews (including the conversos) and the resumption of expansion in the Estado da Índia. Judaism, the author summarizes, will be uprooted through the good example given by the Portuguese. The suggestions made throughout the second half of the tract on how to employ the “music of franchise” to solve the converso problem require that Pedro never forget that God always loved the Jewish people; even from the cross Christ asked forgiveness for the crimes committed against him (Luke 23:34). It is true that the Portuguese were God’s elected people in Ourique. But he never abandoned his first choice, promising that one day all of the Jews would be finally enlightened by the “evangelical torches” supported by Portuguese monarchs who, in this way, act as “quasi-apostles” (quase apóstolos) (Vieira 2014c: 325).31 Therefore, Pedro must take the example of friar Vicente Ferrer (1350-1419), who in a single sermon “converted in Valencia five thousand Jews” (cf. Cátedra 1997). Implicitly, the author of “Vieira’s Paper” is claiming that the missionary’s “word” employed by Friar Ferrer through his “peaceful” evangelical activities is more efficacious than the Inquisition’s frightening “sword.” Explicitly, he is appealing to the prince regent to support the election of bishops according to the requirements of Paul in the First Epistle to Timothy (Timothy 3): “for only virtuous bishops devoted to God will name in their turn virtuous missionaries and preachers who will successfully spread the Gospel among the Hebrews, wherever they are” (Vieira 2014c: 325-36). This suggestion endorses an almost overt critique against the hostile attitudes taken by most of Portugal’s high clergy vis-à-vis the New Christians.

The author of “Vieira’s Paper” concludes the tract by focusing again on his Indian project. In the first place, he calls on the prince regent to follow the magnanimity of previous monarchs in their efforts to attain “the salvation of souls and the expansion of the Lusitanian empire.” This certainly entailed heavy expenses to equip the navy with soldiers, arms, and missionaries and would require new tributes from the people, even against the will of the Cortes (Vieira 214c: 327-330). In light of the absolute character of the ruler over his subjects and his divine task (Vieira 2014c: 334-347), our author encourages Pedro to ignore the parliament and just follow the “fine and Catholic reason of state” prescribed by the pact of Ourique (Vieira 2014c: 333).

It is in this vein that “Vieira’s Paper” ends; glossing on the meaning of two major symbols of Portugal that were revealed in Ourique: the five corners or quinas, which were symbolic of the five wounds of Christ at the cross, and the serpent, which evoked the healing properties of believing in God-the-Son, as prefigured in Numbers 21:8 (Vieira 2014c: 348). The message is unmistakable: Pedro should never desist from following the emblems woven in Portugal’s flag. Note, however, that the symbol of the thirty silver coins, recalling the money received by Judas Iscariot in exchange for handing over Jesus Christ (Matthew 26:15) and often associated with Jewish covetousness and treachery, was never mentioned, probably for obvious rhetorical reasons (Castaño 2001). The same can be said about the silence over Portugal’s concession of Mumbai to England as part of the contract of marriage between Catherine of Braganza (1638-1705) and King Charles II (1630-1685) in 1661 as our author reviews those parts of the Estado da Índia which fell under the foreign, heretic, and infidel hands of the Dutch, the Persians, the Moghul, the king of Arakan, the Imam of Oman, and other princes (Vieira 2014c: 349). According to “Vieira’s Paper,” these significant losses do not mean that the prince regent should abandon imperial aspirations. Quite the contrary. As prophesized by Isaiah, the prince regent must complete the conquest of India because only in this way will Portugal attain its prescribed goal: to unite Jews and Gentiles “into the faithful flock of the Catholic union.” In this way, “the doors of the universe will be opened” to the Portuguese and Pedro will be finally enthroned as the “universal emperor on earth” (Vieira, 2014c: 349). Therefore, instead of vainly pursuing a simple political recognition by the Cortes, Pedro must commit to the legacy of Ourique and in this way, he will finally gain a universal empire.

Note that views of the Estado da Índia as “an increasingly spiritual entity” were shared by contemporary missionaries, who also grounded their millenarian hopes upon the “miracle of Ourique” (Winius 2001: 48-49; Jordán 2003; Zupanov 2007; Xavier 2016). In some cases, it is even possible to identify influences on Vieira’s views (Biedermann 2012). For Jesuit missionaries, like the young Vieira initially preaching in Brazil, “the Portuguese empire was more than a means to safeguard their local missions . . . they begun to understand their own peripheral position in the politics of imperial rivalry, literally and figuratively.” Moreover, “their local missions became theatres of global empire,” especially after our Jesuit joined the court in Portugal (Chakravarti 2018: 231, 243). According to George D. Winius (2001: 42), the successful conquests of the Dutch in Asia during the seventh century stimulated the following rationale akin to those found in “Vieira’s Paper”: “Now of course if something divinely ordained comes in peril, one can only conclude that God's will is being thwarted. But since He is omnipotent, He only permits the hindrance to exist to show His displeasure with, in this case, the sins of children of Portugal. Once they have repented, the divine plan would of course continue to unfold.” Perhaps for this reason “Vieira’s Paper” does not mention Pedro’s refusal to sign a common alliance with the French against the Dutch in India, which “ended any lingering hopes among realistic Portuguese that the Estado da India’s losses of the past half-century might still regained by force,” nor expressed any awareness of the increasing encroachment upon the rights of Portugal’s Padroado through the missionary activities of the Propaganda Fide (Disney 2009, 2: 301; Chakravarti 2018: 299; Xavier and Olival 2018: 139-144).

Such setbacks did not mean that the prince regent had no plans regarding India. According to Glenn J. Ames:

There is every indication that the years commencing with the reign of Prince Regent Pedro (1668) and culminating with the Viceroyalty of Luis de Mendonça Furtado (1671-1677) witnessed a notable reformation campaign. The wide-ranging reforms discussed and implemented during these years emanated from the belief on the part of Pedro, his grandee advisors, and the members of the Overseas Council in Lisbon, that the remaining Asian holdings, if properly administered and exploited, in conjunction with the rich Rios de Cuama region of Mozambique could serve as the basis for a profitable and viable Estado (Ames 2000: 14).

Moreover, Pedro’s pragmatic policies of reform in the extant Estado da India “would ultimately result in a gradual stabilization of the Asian empire after a half century of setbacks in Europe and the East” (Ames 2000: 14). However, these reforms had little in common with the enthusiastic projections of “Vieira’s Paper,” nor with Vieira’s messianic designs and failed plans of 1672 to establish again an Indian Company with converso investment in exchange of a general pardon to be granted to the “men of the nation” by the loving grace of D. Pedro (Chakravarti 2018: 300-308).

As I here argued, the content, form, and historical context of “Vieira’s Paper” indicate a more than probable authorship by Vieira. If so, “Vieira’s Paper” would be a clear example of the way the Jesuit combined in a single discourse the circumstantial and the ideological, pragmatism and belief, theology, and politics. Various crucial topics during Pedro’s regency-such as the power of the parliament and the Inquisition, the authority of the pope and the secular ruler, the New Christian question of integration before and after the affair of Odivelas, the controversial Extermination Law, debates around the reform of Portugal’s Holy Office, and the setbacks suffered by the Portuguese in the Estado da India-alternate with a firm belief in God’s election of the Portuguese and the ensuing task of their rulers to spread Christianity through conquest, evangelization, and the peaceful integration of the converso group as indispensable agents of empire and evangelization. Different rhetorical strategies used in “Vieira’s Paper” explained to the addressee the meaning and implications of leading a “chosen people” which combine an Old Testament sense of particularism with a Pauline call for expansive universalism. Written much in the way Vieira composed his acclaimed sermons, “Vieira’s Paper” maintains the performative overtones and the admonishing-reformative character of the Jesuit’s political writings.

If “Vieira’s Paper” was indeed written by Father António Vieira, this document sheds light on the Jesuit in at least two important respects. First, it nuances a too-rigid periodization by some Vieira scholars between his Lusocentric messianic writings prior to the 1660s and the more universalistic overtones adopted in his unfinished “Clavis Prophetarum” (Real 2008: 15-23). This does not mean that his views did not evolve over time. At least for rhetorical reasons, “Vieira’s Paper” does not employ the controversial lyric prophecies or Trovas of Bandarra (which caused the Inquisition to condemn Vieira), and focuses instead on interpreting his prophetic views on the more consensual “miracle of Ourique.” Second, “Vieira’s Paper” attests to the way the Jesuit approached the New Christian issue in the 1670s. Broadly speaking, Vieira’s activities on behalf of the “men of the nation” in Rome were characterized by an intense political activism through lobbying and spokesmanship, which included circumstantial writings aimed at supporting specific issues and solving ad hoc problems, such as the refutation of the accusations of Odivelas, the concession of a general pardon for conversos, the denunciation of the biased proceedings of the Portuguese Inquisition, and so on.32 In this sense, “Vieira’s Paper” illustrates how specific events and circumstances (e.g., the Extermination Law and the right of Portugal’s New Christians to submit to the pope complaints regarding the Inquisition) did not set aside the articulation of their place in a messianic Lusocentric horizon or the role he conferred to the sons of Israel, whether baptized New Christians or professing Jews, in the advancement of human salvation, as was also elaborated in his universalist opus magnum (Lopes 1999). In this sense, the attitudes in “Viera’s Paper” vis-à-vis the New Christians fully coincides with Ananya Chakravarti’s portrait of Father Vieira as a tenacious missionary (Chakravarti 2018: 231-314) and with what Thomas M. Cohen (1991) sees in Vieira’s persistent fidelity to King Pedro II and his heirs: a strong sense of coherence which combined admonishment and praise, disappointment, and hope.

Manuscripts

Biblioteca da Académia das Ciencias de Lisboa (BACL): série vermelha de manuscritos, mss. 19; 443; 445; 454-A; 455; 450

Biblioteca da Ajuda (BA): Mss.. 44-XIII-43; 51-II-34

Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (BNP): “Conjunto de diplomas oficiais do período da regência de D. João VI,” COD. 805//35.