Introduction

Dental trauma is considered a particular health emergency. The physical impact on dental and support tissues directly affects the functionality and aesthetics of the stomatognathic system and disrupts emotional and economic aspects of life.1,2

A recent systematic review based on 102 studies and 109 data sets reported that traumatic dental injuries to permanente teeth have a global prevalence of 15.2%, representing an estimated 892 million individuals.3 This evidence3 highlights the importance of dental trauma worldwide, which would occupy the fifth place in the Global Burden Disease 2015 if included in the list of major chronic diseases and injuries. Surprisingly, the World Health Organization only considers dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancer in the oral health section.

Thus, dental trauma is a neglected condition that should be included in the public health and research agenda.

A tooth root fracture is caused by a longitudinal, transversal, or oblique force that results in a pattern of fracture that can be vertical, transversal, oblique, or a combination of these.

The tooth root fracture’s diagnosis is challenging because its clinical aspect mirrors the extrusive luxation, and its radiographic aspect may confuse the classification into transversal or oblique tooth root fracture.4 Thus, its diagnosis is given by the complementary evaluation of a periapical radiographic image, two angled horizontal radiographic images, and an occlusal radiographic image. Such exams can be challenging due to the x-ray beam incidence positioning and the patient’s behavior.4,5The complementary examination by cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is also possible, but its availability is still limited.5

The tooth root fracture’s prognosis depends on the injury’s location (apical, middle, or coronal third of the tooth root), stage of root development, degree of displacement (not mandatory), distance between the fragments, and pulp damage.6

These fractures have an estimated 1.2% to 7.0% prevalence in permanent dentition, where the transversal pattern and the cervical third location are the most frequent.7

Since randomized clinical trials are not feasible for reproducing traumatic situations, case reports can provide valuable information about intervention and prognosis, mainly when the traumatic injuries affect the periodontal tissues. This case report aimed to describe a case of immediate management of an oblique tooth root fracture in the middle third concomitante with coronal fragment extrusion in permanent dentition.

Case report

A 14-year-old female patient with good general health attended the dental office immediately after an accident during physical education class. The clinical examination showed incisal unevenness, local bleeding, increased mobility, and displacement of the permanent maxillary left central incisor tooth from its alveolus (Figure 1A). The radiographic assessment demonstrated increased periodontal ligament space and a transverse line in the middle third of the root with coronal fragment extrusion (Figure 1B).

The immediate therapeutic approach was cleaning the traumatized region with 0.9% saline solution (Sorimax®, Farmax, Divinopolis, MG, Brazil), repositioning the extruded coronal fragment about the other teeth’ incisal plane, and stabilizing the occlusion with flexible splints with composite resin (Filtek Z250 XT®, 3M Brasil, Sumaré, SP, Brazil) and 0.3-mm stainless steel wire (CrNi Steel Wire, Morelli, Sorocaba, SP, Brazil) for four weeks. The periapical radiographic imaging exam performed after repositioning the fragment showed the root fracture reduction line. The patient was prescribed a combined therapy of nimesulide (100 mg) 2 times a day for 3 days and amoxicillin (500 mg) 3 times a day for 5 days. Instructions were given to the parents and the patient, especially about refraining from recreational school activities, oral hygiene routine, topical use of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash, and follow-up visits after 7 days, 4 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months.

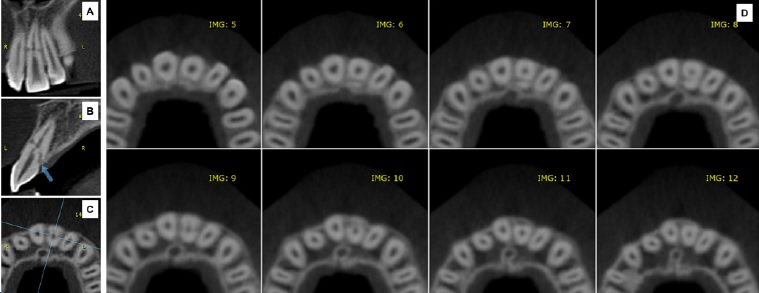

After 7 days, the patient was healing well without painful symptoms, fistula, tooth discoloration, or any radiographic aspect of pulp degeneration. Clinical and radiographic conditions remained satisfactory at the 4-week, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups. Pulp vitality was confirmed by termal and percussion tests after 12 months (Figure 2A). Signs of repair between fractured segments were observed in the radiographic examination (Figure 2B). CBCT confirmed the diagnosis of oblique tooth root fracture and demonstrated hard tissue formation on the walls of the tooth root canal over the fracture line to unite the fractured segments (Figure 3 A-D).

Discussion and conclusions

Managing dental trauma is challenging, especially when it involves support tissues and is associated with tooth displacement. Even in children and adolescents with wellknown positive behavior at the consultation, urgent care in dental trauma cases represents an unusually stressful situation that can affect the behavior of the patient, parents, and dentist. Ideally, urgent consultations should be provided by dentists specifically trained for diagnosis, treatment protocols, and stress-coping strategies in that context. However, in reality, prompt treatment is rarely offered in these circumstances, which may result in unsatisfactory outcomes for both patients and practitioners. In this clinical case, the immediate first aid, the dentist’s expertise, and the patient’s and parents’ compliance with the instructions and follow-up appointments favored the treatment’s success. Noteworthy, immediate assistance contributes to a favorable prognosis, mainly in luxations,8 tooth root fractures,9 and dental avulsions.10

Tooth root fractures involve different dental and periodontal tissues, making the healing process more challenging and more susceptible to complications, especially if the coronal fragment is displaced from the root. In such a scenario, the pulp may be distended or completely sectioned (lacerated) at the fracture site, causing a reduction or cut-off of blood supply.

In some cases, the blood supply may recover, and the pulp heal properly. However, in more severe situations, pulpal necrosis associated with root canal infection can occur, and this is more likely to happen if the traumatic incident is associated with a tooth crack, fracture, or dislocation.11-13 Our case demonstrates that pulp healing is possible even if the coronal fragment is extensively displaced. The patient’s age (young dental pulp) and the immediate reduction/stabilization of the tooth root fracture may have contributed to this favorable outcome. In addition, based on the radiographic images, the apical fragment did not appear to have been displaced or damaged during the trauma.

Andreasen and Hjørting-Hansen12 described four prognostic possibilities for root fracture: healing with hard tissue, fibrous connective tissue, or both, or development of infectious granulation tissue. In our case, the fragments’ root canal anatomy remained unaltered, while a union of pieces with hard tissue was observed during the follow-up. Thus, we could predict healing based on the formation of reactionary dentin on the root canal walls over the fracture line associated with remodeling of the fracture periphery by reabsorption and new cementum.

A study showed pulp activity starting right after a tooth root fracture in dogs. Furthermore, there is competition between periodontal fibers and pulp tissue.11 The vitality of the non-extruded root portion’s pulp and periodontium could have boosted the healing process of the extruded portion, which was repositioned and stabilized. Therefore, additional measures, such as medication prescriptions and instructions for refraining from recreational school activities, were taken. Insufficient scientific evidence supports treatment success using anti-inflammatory and antibiotic medication. However, the anti-inflammatory and antibiotic were chosen to suppress inflammation and infection caused by the impact, the extension of the extruded fragment, and the level of contamination of the accident environment. The patient was instructed to refrain from recreational activities due to the risk of new trauma in the region and the case’s complexity.4

CBCT scan significantly complemented the diagnosis of the case. According to Bourguignon et al.,4 the radiographic protocol requires at least one periapical radiograph, which can be very difficult depending on the child’s age and behavior. Still, the radiographic examination can be nonspecific. A study by Bornstein et al.5 showed the advantage of CBCT imaging over conventional imaging, pointing out that the first contributed to the diagnosis of 70% of root fractures. Furthermore, most root fractures diagnosed by CBCT were not submitted to endodontic treatment, suggesting that earlier diagnosis leads to lower rates of radical treatment.

The scientific evidence regarding the use of CBCT in children and adolescents is scarce. However, Oenning et al.,14 through a multicenter and multidisciplinary project-DIMITRA (pediatric dentomaxillofacial imaging: an investigation on risks induced by low-dose radiation), gathered state-of-art information regarding image quality and dose, and associating it with DIMITRA’s members’ expertise, provided an indication-oriented and patient-specific position statement. Among the main indications were the diagnosis and follow-up of traumatic injuries and root fractures. Noteworthy, the safety protocol for protecting the child from ionizing radiation is mandatory.

Finally, perspectives concerning the need and possibility of future orthodontic treatment are important. Risk factos for bad orthodontic outcomes are individual genetic susceptibility, systemic diseases, root morphology anomalies, previous endodontic treatment, and dental trauma. Injuries during orthodontic treatment, such as root resorption, can be prevented by controlling risk factors. Periodic radiographic control during treatment is necessary to detect the occurrence of root damage and quickly reassess treatment goals. Previous history of dental trauma is not an absolute contraindication to starting orthodontic treatment if the treatment duration is as short as possible.15

The present case followed the International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT) guidelines for diagnosing, treating, and following up a tooth root fracture.4 Although these guidelines were based on information from animal studies, case reports, case series, retrospective cohort studies, and expert opinions, the clinical success of this case reemphasizes their importance in a real-life situation.

The immediate management of an oblique tooth root fracture in the middle third concomitant with coronal fragment extrusion using a standardized approach that includes repositioning the fragment, using a flexible splint, and parents’ and patient’s compliance resulted in favorable healing with mineralized tissue over the fracture line.