Introduction

Osteoma is a benign and slowly growing neoplasm characterized by the proliferation of mature compact bone, cancellous bone, or a combination of both. It can occur in peripheral, central, or extraskeletal forms, with initial reports dating back to 1935.1 The peripheral variant is prevalent and is frequently found in the frontal, ethmoidal, and maxillary paranasal sinuses.

Lesions affecting the maxillomandibular region are rare. In Gardner’s syndrome, multiple osteomas occur.2-4 Peripheral osteomas are found in a wide age range, from teenagers to older adults, mainly in males. These lesions are typically singular, often resembling a mushroom, and are generally asymptomatic. However, the lesion’s location and size may result in overlying trauma, leading to swelling, pain, aesthetic distortion, and functional limitations.5 On radiographic exams, peripheral osteomas appear as well-defined radiopaque lesions with a rounded or oval shape connected to the cortex by either a broad base or a pedicle.6,7The slow growth rate of osteomas justifies a conservative approach for asymptomatic cases, while surgical removal is recommended when the lesion causes symptoms, is actively growing, or leads to aesthetic concerns and functional limitations.3,4,7

In this context, this article presents an atypical case of osteoma characterized by unusual location, radiographic presentation, and patient’s age. Specifically, it describes an unusual case of an 11-year-old male patient presenting with a peripheral osteoma on the right retromolar trigone region.

Case report

An 11-year-old male patient was referred to the Stomatology Service of the School of Dentistry of the Federal University of Uberlândia to evaluate a “nodule on the right cheek.” The initial interview revealed that the lesion had been noticed a month earlier. The patient was initially asymptomatic and later developed pain during mastication. An extraoral examination revealed noticeable swelling on the right side of the patient’s face, resulting in slight facial asymmetry (Figure 1).

Further examination, involving both palpation and intraoral inspection, revealed a solitary lesion with a hardened consistency originating from the retromolar area of the alveolar ridge. Although the mucosal covering appeared normal, occlusal marks were evident from adjacent teeth (Figure 2). There were no signs of infection, history of facial trauma, or relevant medical background.

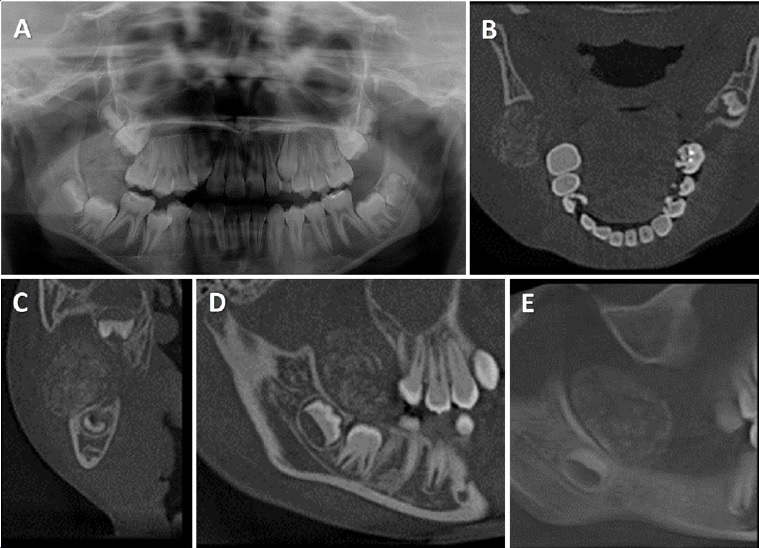

Panoramic radiography revealed a well-defined radiopaque mass on the posterior right side of the mandible, positioned above the erupting lower second molar (Figure 3A). Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) revealed a well-delineated mixed unilocular lesion with a pedunculated appearance, measuring approximately 30x19x22 mm and originating from the alveolar ridge surface (Figure 3B-E).

Figure 3 (A) Panoramic radiography showing radiopaque lesion on the posterior right side of the mandible, superiorly to the lower second molar; (B-E) CBCT showing a mixed lesion with pedunculated appearance in the right retromolar trigone region.

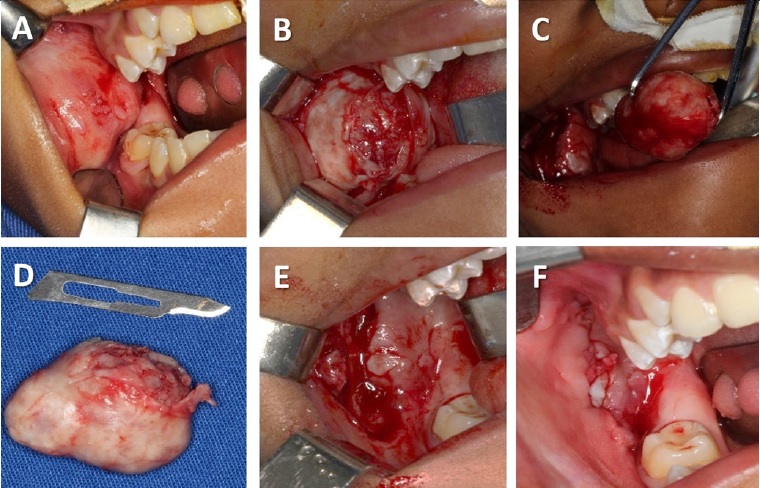

Three potential diagnoses were considered based on the information collected: peripheral ossifying fibroma, peripheral osteoma, and parosteal osteosarcoma. An incisional biopsy was performed, and histopathological analysis revealed fragments composed mainly of dense connective tissue with moderate mononuclear leucocytic infiltration, permeated by scarce globular and trabecular mature bone tissue without any sign of cellular atypia. These findings were interpreted as a benign lesion, aligning with the hypothesis of peripheral ossifying fibroma, although not excluding the possibility of a peripheral osteoma. The lesion was then surgically excised under general anesthesia, using a linear incision and gentle dissection for complete removal. Osteoplasty using a Maxicut bur (American Burs, Brazil) was performed, followed by irrigation with a 0.9% saline solution and closure with resorbable sutures (Monocryl 4.0, Ethicon Inc, USA) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 (A) Intraoral aspect; (B) Surgical access; (C) Exeresis of the lesion; (D) Excised specimen; (E) Final surgical aspect after the lesion removal; (F) Sutures.

During the hospital stay, intravenous antibiotics (cefazolin 1000 mg), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (tenoxicam 20 mg), and analgesics (dipyrone 1000 mg) were administered. The post-operative medication prescribed included oral antibiotics (amoxicillin 500 mg), na anti-inflammatory (nimesulide 100 mg), and an analgesic (dipyrone 500 mg), along with oral rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate after hospital discharge. Follow-up appointments every 2 days monitored mucosal healing until complete recovery.

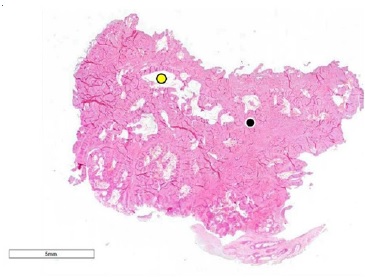

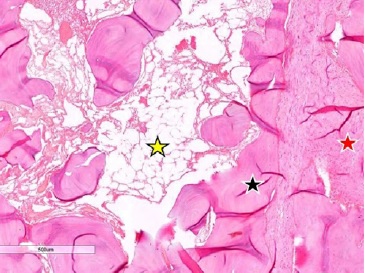

The excised material underwent histopathological analysis, revealing normal bone structure characterized by a spongy architecture, fibro-fatty marrow, minor hematopoietic tissue, and superficial foci of chronic inflammatory infiltrate. As a result, the possibility of a reactive lesion, such as a peripheral ossifying fibroma, was discarded. Given the non-simple bony protrusion and deviation from the mandible’s growth pattern, the pathology indicated the clinical hypothesis of a peripheral osteoma (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5 Photomicrography of the sample obtained by surgical excision showing a fragment composed of compact bone tissue with small spaces of fibro-fatty marrow (hematoxylin-eosin stain).

Figure 6 Presence of mature/lamellar bone (black star), fatty marrow (yellow star), and fibrous marrow (red star) (hematoxylin-eosin stain).

The patient’s condition has been monitored through both clinical examinations and radiographic assessments. After a year of follow-up, no recurrence or changes were observed at the surgical site.

Discussion and conclusions

We present a case report involving an 11-year-old male patient who exhibited a peripheral osteoma in the right retromolar trigone region. While osteomas can potentially occur at any

age, their occurrence in children is rare unless associated with Gardner’s syndrome, as noted by Chattopadhyay et al.8 Remarkably, in the present case, the patient did not exhibit any systemic alterations or a history of facial trauma. Studies by Hasan et al.,3 Tilaveridis et al.,4 and Khandelwal et al.9 support that solitary peripheral osteomas of the jaw bones are extremely uncommon, affecting the mandible more frequently than the maxilla. In the mandible, they affect the angle and the mandibular body’s inferior border more frequently. However, the current case describes a solitary peripheral osteoma in the right retromolar trigone region, a location not previously documented in available English literature.

Both Khandelwal et al.9 and Agrawal et al.7 emphasize that these lesions exhibit slow growth and typically manifest as na asymptomatic increase in volume, often detected incidentally through routine radiographic examinations. This description contrasts with the present case, where the swelling was noted after one month, coinciding with the onset of facial asymmetry and discomfort while chewing.

Radiographically, peripheral osteomas are characterized by a well-circumscribed radiopaque mass, typically round or ovoid in shape, as described by Agrawal et al.7 This description partially aligns with the current case, as it exhibited well-defined margins and an ovoid appearance. However, there was a disparity in terms of density compared to the literature: instead of a consistent, homogenous radiopaque appearance, the observed lesion presented a mixed nature. CBCT examination allowed an accurate discernment of the internal density, which led to hypothesizing that the lesion might not have reached the level of maturity described in the literature.

Initially, we considered the potential diagnosis of a peripheral ossifying fibroma, one of the differential diagnoses for peripheral osteoma and among the most prevalent reactive inflammatory hyperplastic lesions in the oral cavity.10 Peripheral ossifying fibromas are reactive jaw lesions that typically exhibit slow growth, are asymptomatic, and manifest as a proliferation of fibrous tissue containing varying amounts of bone, cementum, or a combination of both. Typically localized in the alveolar ridge, these lesions are commonly associated with biofilm accumulation, leading to an inflammatory environment that activates periodontal cells and causes the formation of metaplastic bone within a pre-existing fibrous tumor.

Clinically, peripheral ossifying fibromas often present as elevated ovoid lesions with a smooth or ulcerated surface, displaying a normal color similar to the adjacent mucosa. The lesions may exhibit a sessile or pedunculated base and possess firm consistency.11 Radiographically, these fibromas typically exhibit well-defined edges, often accompanied by a thin radiolucent line representing a fibrous capsule. Their internal structure presents a mixed radiolucent-radiopaque density pattern, influenced by the shape and amount of calcified material.

Tomographic images usually reveal a hyperdense mass enclosed by a hypodense halo without cortical bone invasion, differentiating it from peripheral osteomas, as in the current case.12 A definitive diagnosis of peripheral ossifying fibroma is usually established through histological examination, which shows multinucleated giant cells permeated by connective tissue cells, possibly accompanied by areas of reactional bone or dystrophic calcifications. However, in the present case, local irritating factors (biofilm, mechanic trauma) were absent, and the histopathological examination revealed mature bone throughout the analyzed specimen. This finding effectively ruled out the possibility of diagnosing the lesion as a peripheral ossifying fibroma.

Another potential differential diagnosis under consideration was parosteal osteosarcoma, prompted by the absence of continuity between the lesion and the underlying bone-a characteristic feature of parosteal osteosarcomas. Parosteal osteosarcomas typically present as lobulated nodules firmly attached to the cortical bone. Moreover, parosteal osteossarcomas often exhibit a thin periosteal radiolucency, commonly called the “string sign,” which separates the tumor from the adjacent cortex in approximately 30% of cases.12 However, in malignant cases, these lesions comprise poorly differentiated malignant cartilage lobes containing central calcification.

This particular histopathological feature was not observed in the present case, leading to the exclusion of parosteal osteosarcoma as a potential diagnosis due to the lesion’s predominantly benign cellular appearance.13 In the current case, there were no histopathological signs of malignancy, and the lesion was entirely composed of mature bone.

Such microscopic features can be found in torus and exostosis; however, these conditions were not considered in the present case due to the lesion’s location and the reported rapid growth.

The treatment strategy chosen in this case aligns with the literature. Generally, invasive treatments are selected to alleviate pressure on adjacent structures. In this instance, surgical excision was performed due to the local discomfort and facial asymmetry reported by the patient. This surgical intervention is supported by the literature, which recommends surgical management in symptomatic cases3,4and in osteomas that exhibit rapid growth14 - both characteristics observed in this particular case. Furthermore, the lesion’s obstruction of the lower second molar’s eruption path also justified the decision for surgical management.

After one year of follow-up, the patient has reported no complaints. Additionally, no clinical or radiographic signs of recurrence have been observed, further confirming the successful outcome of the surgical intervention.

In conclusion, while peripheral osteoma is generally recognized for its typical appearance, our case report emphasizes potential variations in its radiographic features. These diferente presentations may involve mixed lesions and occurrence in regions beyond the commonly associated paranasal sinuses and inferior cortex of the mandible. These findings highlight the importance of considering a diverse range of presentations in the diagnosis of such lesions.