Introduction

Mycotic aneurysm is a rare entity with rapid progression, which can be fatal without appropriate treatment. This clinical entity is caused by microbial infection of the aortic wall, which can lead to rapid degradation and formation of a localized aneurysm or by infection of a pre-existing aneurysm.1,2 Mycotic aneurysms are more often caused by bloodstream infection. Still, they may develop due to septic emboli to the vasa vasorum or by direct spread from infected tissue adjacent to the vascular wall.1,3 The incidence of rupture is higher than that of degenerative aneurysms, with a high mortality rate, and commonly located in the visceral segment of the aorta.4 The microbial infection is predominantly bacterial, with Staphylococcus, Salmonella, and Streptococcus species being the most frequently reported bacteria, but the spectrum of other organisms is widening. Klebsiella pneumoniae is a rare reported causative agent.4,5,6 Only in sporadic cases have fungi agents been accounted for the development of mycotic aneurysm. At the same time, viruses have not been described in the literature.2,3

Treatment success depends on the correct and timely diagnosis with prompt initiation of broad or antibiogram-directed antibiotic treatment, followed by surgery whenever possible to defer the repair.4,7 The standard intervention has been open surgical repair with resection and extensive debridement of the infected tissue followed by reconstruction with an in-situ graft or extra-anatomic revascularization and aortic ligation. Endovascular techniques have gained greater visibility in the treatment of mycotic aneurysms. However, their use is still not consensual as a definitive treatment, remaining as valid bridging interventions in emergent settings.7,8

Although several studies have been published, there are no clear guidelines for the diagnosis, management, or treatment of mycotic aneurysms, which in this case was further complicated by the rarity of the causative agent and the immunocompromised status of the patient.

Case report

A 58-year-old man with a previous history of treated HIV-1 infection with good immunovirological staging treated squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal, and chronic gastritis presented to the emergency department with complaints of back pain, malaise, fever, and rigors with three days of evolution. Laboratory findings revealed a slight increase in inflammatory parameters. This was interpreted as renal colic, and he was discharged with oral medication. Because of worsening back pain associated with macroscopic hematuria, the patient returned to the emergency department three days later. At the time of admission, he presented localized back pain while the abdomen was soft and not tender. No cardiac or pulmonary abnormalities were noted on the physical examination, nor were any joint pain or skin changes observed. The patient’s mental status and neurological exam were normal. The patient was normotensive with a rhythmic pulse of 93 beats per minute and febrile (37.8°C).

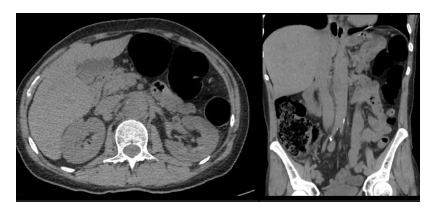

Laboratory findings showed a worsening of inflammatory parameters relative to the initial presentation. A computerized tomography (CT) showed non-obstructive renal lithiasis and raised suspicion of pyelonephritis, while an abdominal ultrasound revealed a vesical lesion of unknown etiology (Figure 1). With a presumed diagnosis of pyelonephritis, the patient was hospitalized to start broad endovenous antibiotics with ceftriaxone 1gr IV each day and to study the vesical lesion further.

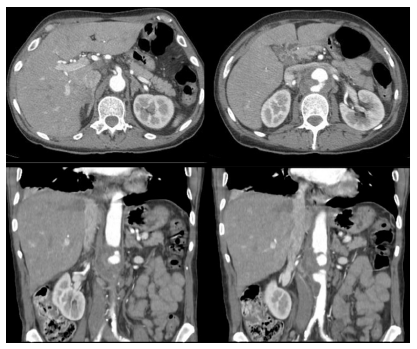

On the third day of hospitalization, the patient developed hypoxia, which led to the performance of a chest CT to exclude pulmonary embolism. Contrast was not administered then due to a suspicion of allergy to contrast agents, which were later excluded. The CT showed a right base pneumonia with pleural effusion. Because of no improvement of the back pain despite escalating analgesic therapy, the patient performed a magnetic resonance, which confirmed the suspicion of infectious spondylodiscitis of the 2nd and 3rd lumbar vertebrae. To further investigate a bladder lesion diagnosed initially on ultrasound, a CT angiography (CTA) was performed 14 days after admission. The CTA showed a mycotic aneurysm of the abdominal aorta involving the visceral plaque with a transversal maximum diameter of 55 mm and a total cranio-caudal length of 70 mm, starting just below the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Computed tomography at admission. Pararenal aorta with slight dilatation can be noted in the axial (left) and coronal (right) planes

Figure 2 Computed tomography angiography two weeks after hospital admission. Aneurysm formation with aortic wall thickening irregularity and asymmetric aneurysm formation can be noted in the axial (top) and coronal (bottom) slices

The microbiological examinations at admission revealed positive blood cultures for Klebsiella pneumoniae, sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and gentamicin and resistant to ampicillin and amoxicillin. The urine cultures were negative, and a transthoracic echocardiogram excluded vegetation on the heart valves. As such, Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia with bone, pulmonary, and vascular involvement was assumed, and directed antibiotic therapy with intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was initiated.

At this point, the vascular surgery team was involved in a multidisciplinary team that included orthopedics and infectious diseases specialists. From a vertebral morphological point of view, the patient didn’t benefit from surgical fixation of the spine since there was no evidence of collapse or deformity and had an indication to maintain antibiotic therapy and surveillance for signs of neurological compromise. As the patient was hemodynamically stable, without any hemoglobin level decreases or evidence of aneurysm rupture on the performed imaging, it was decided that the patient should comply with a minimum of 6 weeks of directed antibiotic therapy before undergoing surgery, under close observation and tight blood pressure control.

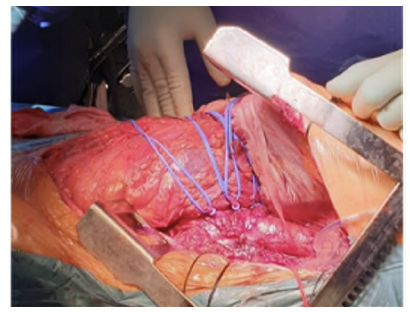

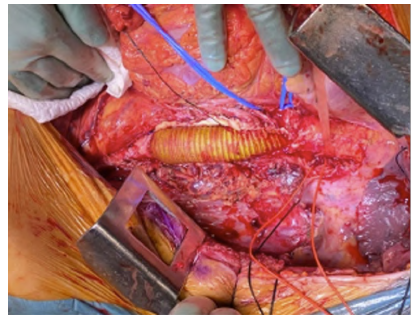

On the 49th day of hospital stay, after six weeks of antibiotic therapy and confirmed negative blood cultures, the patient underwent an aorto-aortic interposition with a 24mm silver-impregnated Dacron® prosthesis from a left thoracophrenolaparotomy approach (Figures 3 and 4). The intervention was performed in collaboration with cardiac surgery under left heart bypass and warm perfusion for the SMA and celiac trunk (CeT), while a Custodiol® cold perfusion of the renal arteries was used. After extensive local debridement of all infected tissues, aortic wall, and thrombus, samples were sent for histological examination and microbiological culture analysis, which returned positive for Candida albicans (rare colonies) and negative for Klebsiella pneumoniae. The proximal anastomosis with patch configuration encompassing the visceral arteries (CeT, SMA, and renal arteries) avoided the need for selective reimplantation, and the total aortic clamping time was 58 minutes. The inferior mesenteric artery was ligated. An omental flap was transposed to cover the graft and the anastomoses. An antifungal was initiated and maintained six weeks after surgery (caspofungin IV was subsequently switched to fluconazole per os at discharge). The patient received another six weeks of antibiotic treatment after surgery, with a switch to oral therapy at the time of discharge.

Figure 3 Intraoperative image before aortic reconstruction. The mycotic aneurysm can be noted. Visceral arteries are referenced with vessel loops.

Figure 4 Intraoperative image after aortic reconstruction. An interposition graft, with a beveled proximal anastomosis encompassing the visceral plaque, can be noted.

The recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged four weeks after surgery. Before discharge, he performed a CTA that demonstrated anastomotic integrity and the absence of abscess formation. The patient was also followed at the Infectious Diseases clinic, with repeated negative blood cultures over the first 12 months after surgery. At the last appointment, 18 months after the surgery, he was asymptomatic and had returned to work.

Discussion

Mycotic aneurysm, recently named infective native aortic aneurysm (INAA), is an uncommon disease with a particularly high mortality rate. Management of this entity is more difficult than that of a degenerative aneurysm due to the concurrent infection and high risk of rupture, demanding expeditious and extensive treatment. The conventional treatment includes antibiotics combined with surgery (endovascular or open). Prompt surgery is generally recommended irrespective of aneurysm size due to the high risk of rupture without treatment.7 However, different authors proposed a more stepwise treatment based on clinical surveillance. For hemodynamically stable patients who respond to medical therapy (symptoms and inflammatory markers improvement), a delayed surgical repair may be offered to accrue the maximum benefit of antibiotic treatment and reduce the risk of postoperative infection recurrence associated with postoperative mortality. Intervention when blood cultures are negative could be the desirable goal.4,6,9

In the presented case, Ceftriaxone 1g IV was initiated due to suspicion of pyelonephritis, which was adjusted four days later after the bloodstream cultures resulted in amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. After the mycotic aneurysm diagnosis, the decision on the duration of therapy and timing of surgery was made in a multidisciplinary discussion with Infectious Disease specialists and accounted for the HIV+ status of the patient. Given the good response to antibiotic therapy, with apyrexia and inflammatory markers improvement and hemodynamic stability, the decision to withhold surgical repair for six weeks to allow for adequate antibiogram-directed antibiotic therapy before surgery. There are no clear recommendations on the optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy before or after surgery. The ESVS guidelines recommend postoperative antimicrobial therapy for durations ranging from 6 weeks to 6 months or 12 months, or even lifelong therapy for some cases.7 The agent and duration of antibiotic treatment should be decided on an individual basis, preferentially discussed in a multidisciplinary team. It should be adjusted to the cultured microorganism (blood cultures or surgical specimens), type of surgical repair, and immunological status of the patient.3,7,9

In the era of extensive antibiotic use, the bacteriological spectrum of the usually involved agents is broad, with different organisms being increasingly identified and varying trends according to the region of the globe. HIV+ patients show a different microbiological etiology, with Treponema pallidum and Mycobacterium spp. being common pathogens.2Klebsiella pneumoniae is a rare causative agent, even in HIV+ patients, according to available literature.4,5,6,10 In addition to guided antibiotic therapy, conventional treatment includes open repair as the gold standard for definitive treatment, preferentially with autologous veins, cryopreserved arteries, bovine pericardium, or silver-impregnated prosthetic grafts.7 Since the use of an autologous vein would increase the time and surgical aggression in an already fragile patient, and due to the risk of aneurysmal degeneration of the bovine pericardium, our choice was to use a silver prosthetic graft, as cryopreserved grafts are not available at our center.

There is a growing trend towards treating mycotic aneurysms endovascularly, which may be accepted as an alternative to open repair for high-risk patients with well-controlled infections. However, consensus cannot be achieved due to the significant diversity in the literature.4,7In the presented case, open aortic repair was preferred due to the patient’s relatively young age and aneurysm morphology.

Conclussion

We present a case of acute mycotic aneurysm presenting simultaneously with spondylodiscitis and pneumonia in a patient with known HIV infection. In this case, whether the cause of the mycotic aneurysm was hematogenous dissemination from the pneumonia focus or by contiguity from the lumbar spondylodiscitis remains unclear. Early diagnosis and adequate treatment (active surgical and antibiotic treatment with insufficient dosage and duration) are essential for improving survival. Still, due to the rarity and heterogeneity of the patients, there is a lack of robust evidence to guide treatment.