Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Medievalista

versão On-line ISSN 1646-740X

Medievalista no.29 Lisboa jan. 2021

https://doi.org/10.4000/medievalista.3867

DOSSIER

Producing the Bestiary: From Text to Image

Produzindo o bestiário: do texto à imagem

Ilya Dines1

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1867-9184

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1867-9184

1Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. ilyamdemontibus@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

In this paper, I investigate the relationship between the text and the images in medieval Latin bestiary manuscripts. Medieval bestiaries, which are derived from the ancient Physiologus, comprise a nearly 1800-year-old tradition and have spawned several hundreds of copies throughout Europe, including a smaller subset of Latin bestiaries. Summarizing the first ever comprehensive analysis of the entire corpus of Latin bestiaries, this paper examines the patterns of deviations, or exceptions from the rigorous canon governing bestiary illustrations. I use the deviations to investigate the relationship between the work of the scribe and that of the artist in the production of bestiary manuscripts in order to determine to what extent medieval artists used already existing illustrations, and, conversely, when and to what extent they were willing or able to deviate from the canon. In the latter case, I try to explore the artist’s possible motivations, as well as the reasons for choosing specific motifs.

Keywords: Physiologus; Bestiaries; Deviations; Manuscripts; Images.

RESUMO

Neste artigo, investigo a relação entre o texto e as imagens nos bestiários latinos medievais. Os bestiários medievais, derivados do antigo Physiologus, remontam a uma tradição de quase 1800 anos e geraram várias centenas de cópias em toda a Europa, incluindo um subconjunto menor de bestiários latinos. Resumindo a primeira análise abrangente de todo o corpus de bestiários latinos, este artigo examina os padrões de desvios ou exceções do cânone que rege as ilustrações de bestiários. Eu analiso os desvios para investigar a relação entre o trabalho do escriba e o do artista na produção de manuscritos bestiários, a fim de determinar em que medida os artistas medievais usavam ilustrações já existentes e, inversamente, quando e em que medida estavam dispostos, ou capazes, a desviarem-se do cânone. Neste último caso, procuro explorar as possíveis motivações do artista, bem como as razões para a escolha de motivos específicos.

Palavras-chave: Physiologus; Bestiários; Desvios; Manuscritos; Imagens.

1. The Physiologus and bestiaries

The text entitled the Physiologus[1] was written in Greek in Alexandria, at the end of the second or the beginning of the 3rd century CE. It is comprised of approximately forty-nine chapters on animals, birds, and precious stones. The original manuscript is not extant, and thus we have no definitive way of judging whether or not the work was illustrated right from the beginning. Around the 4th or 5th century the Physiologus was translated into Latin, but again we do not possess an early manuscript of that translation. Our earliest copies of the Latin text date back to around 800 CE, when several manuscripts were produced somewhere in Northern France[2]. Likewise, we possess two illustrated copies from the 9th or 10th century containing from twenty-six to thirty-six chapters[3]. To what extent the copyists followed the original Physiologus illustrations remains unknown and belongs mostly to the realm of speculation, as the earliest surviving copy of the Greek Physiologus dates back to the 11th century[4].

The first bestiaries (those of the BIs Family) were generally the same versions of the Latin Physiologus supplemented by additions from the Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville and from some other texts. Later, the tradition of composing and illustrating bestiaries spread throughout Europe, especially France, and into various other European countries - Flanders, Germany, and others.

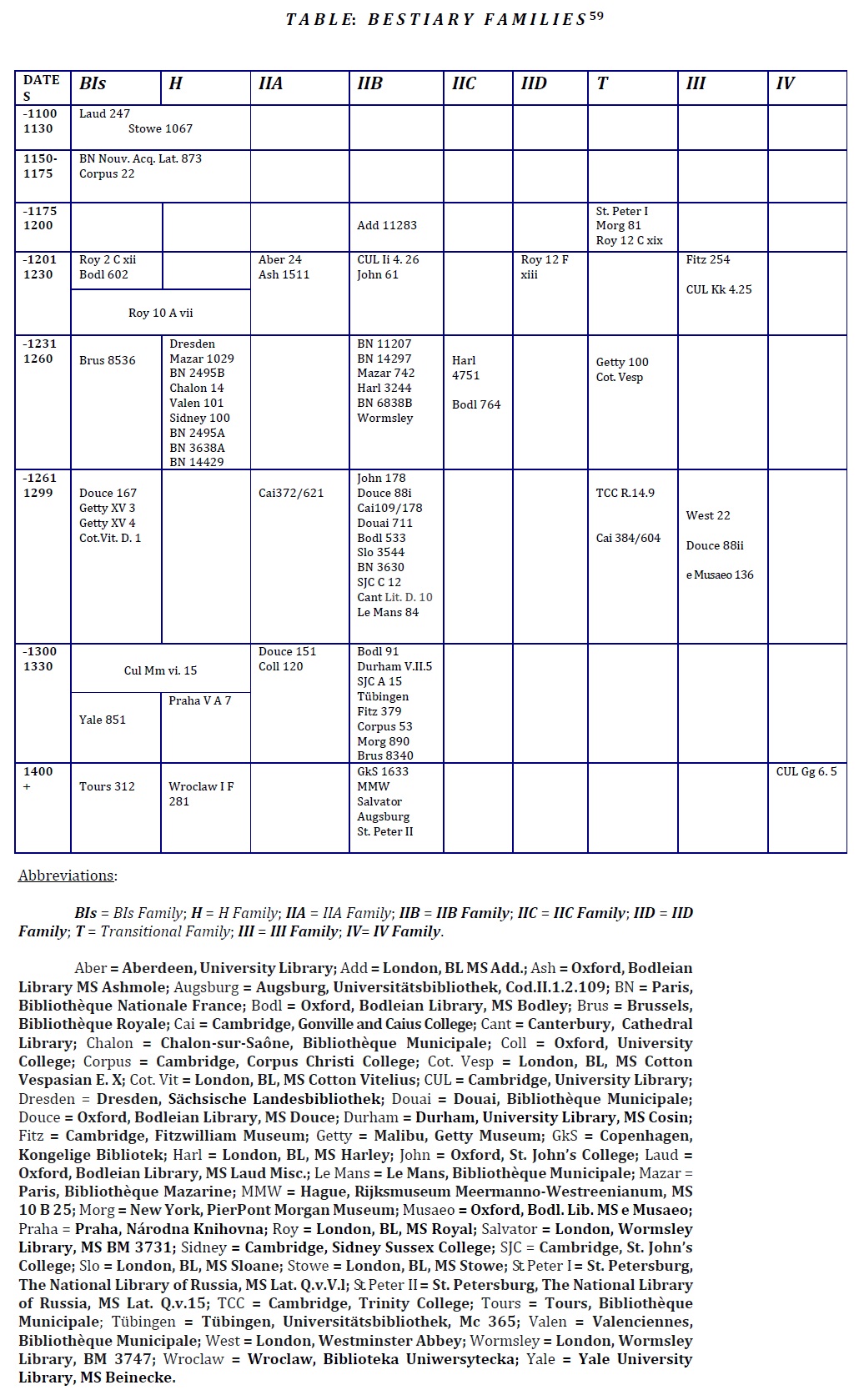

All Latin bestiaries have been divided into groups called families, according to the order of their chapters. This classification was first made by M. R. James and later refined by F. McCulloch, B. Yapp and the author of this article[5]. My classification is shown in the table of bestiary manuscripts at the end of this article. The later version, the H Family, represents a paraphrased BIs text with various additions. This version was mainly popular in France.

The tradition of the bestiaries reached England somewhere in the beginning of the 12th century. Starting around the very end of the 12th or the beginning of the 13th century, long bestiaries (those of the Second, Transitional and Third families), containing between 110 and 150 chapters, appeared in that country. These texts include numerous additions taken from various encyclopedic and theological sources. It is thanks to these versions that the genre came to be one of the most popular genres of medieval literature. It was used primarily as a didactic and pedagogical tool for teaching novices, young monks and cathedral clergy. The era of the bestiaries ended in the middle of the 16th century, marked by the wide-spread dissolution of monasteries in Europe. From this era, we possess about ninety-five bestiary manuscripts written in Latin, on which I focus in this article[6].

About sixty bestiary manuscripts are illuminated. Depending on the version of the bestiary and on the specific manuscript, the number of illustrated chapters varies from about 30 in the earliest families (BIs and H) to 150 in later families, totaling approximately 5000 images.

2. Deviations[7]

2.1. Minor deviations

Undertaking the first systematic scholarly analysis of the entire corpus of extant Latin bestiary manuscripts, I discovered that the overwhelming majority of the images - on the order of 99% - are fairly consistent, in that the same subject is portrayed in the same way, giving evidence of a fairly rigorous pictorial canon. The bestiary, in other words, is a very conservative genre. However, there are exceptions. A not-inconsiderable number of the images show different, sometimes strikingly different, pictorial treatments of the subject. A close examination of these variations, or deviations, suggests two main explanations for the differences. As I show below in more detail, many of the deviations appear to follow a thoughtful - one might even say, individual - reading of the text, challenging the conventional view that manuscript illustrators often did not read the text. A secondary explanation has to do with the primacy of Biblical imagery in the cultural milieu in which the artists operated.

Some of these deviations are relatively minor and do not appear to be grounded in the text of the bestiary. For example, while most conventional bestiary images depict the animal referred to in the accompanying text in the manner described - i.e., showing its specific attributes or activities discussed therein, - these minor deviations simply portray a creature without any textual elucidation. Such omissions are particularly noticeable in most chapters concerned with birds, fish, snakes, and insects, although not in those concerned with beasts. Other minor deviations consist of variations, such as a hunter shown with a bow rather than a spear. Similarly, this can be observed in the popular scene of Adam naming the animals: the deviation almost always contains creatures not referred to in the corresponding chapter[8]. Other examples can be seen in the illustrations of the chapter about the aspis, which is a venomous creature living in a cavern. The text says that when a charmer wants to draw it forth from its place, he sings certain songs, which are supposed to put the aspis to sleep. The charmer at times appears with a shield, while at other times he is portrayed with a scroll of magic formulae[9] .

Other examples of minor deviations can be seen in the scenes where the fox carries a goose in its mouth - contrary to the canonical illustrations, where a fox pretending to be dead is about to devour the birds perched on its torso[10]. To these cases can be added scenes illustrating work by animals and humans where instead of the standard single animal, several animals or an animal and a man appear, as for instance, in the illustration to the chapter on horses[11], or in a scene in which a man is shown placing a burden on a donkey’s back[12], or one showing a man urging his donkey toward a watermill[13], or two men and two donkeys[14]. In the London, BL MS Royal 12 F xiii, f. 37v, a man is shown plowing with a pair of oxen in the chapter on the ox[15], while in Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 254, in the chapter on the boar, a boar is shown being attacked by dogs[16]. London, BL MS Harley 3244, f. 48r also shows a man mounted on a dromedary[17]. All these are relatively minor variations that do not appear to carry any discernible special significance and could be merely based on scenes of ordinary life.

In contrast, there are more significant variations, as for instance those in the scene of the white bird called caladrius, known for foretelling the outcome of an illness. If the bird looks upon the face of a sick person, the sufferer will be healed; if it turns away, the disease is fatal. The conventional rendering depicts the bird as gazing upon the sick person’s face, which means he will recover from his illness; however, there are five or six exceptions that show the caladrius turning away, which portends doom for the patient[18]. Again, in canonical illustrations of the chapter on the panther, the panther and the dragon appear together, since the text describes the dragon as running away from the panther, in contrast to other animals who are attracted by its sweet breath. However, there are several cases where a dragon does not appear at all in the chapter on the panther[19]. Similarly, the chapter on the tigress describes the trick used by the hunter to steal a cub from a tigress[20]. However, in the manuscript Oxford, Bodl. Lib., MS e Musaeo 136, f. 18v both the hunter and the tiger cub are absent, and only the tigress appears, looking distinctly wolf-like. Likewise, in the Copenhagen bestiary, f. 2v mentioned above, a lucky hunter, holding a cub, is shown in the process of escaping - presumably from the tigress, which is, however, absent from the scene[21].

2.2. Significant deviations

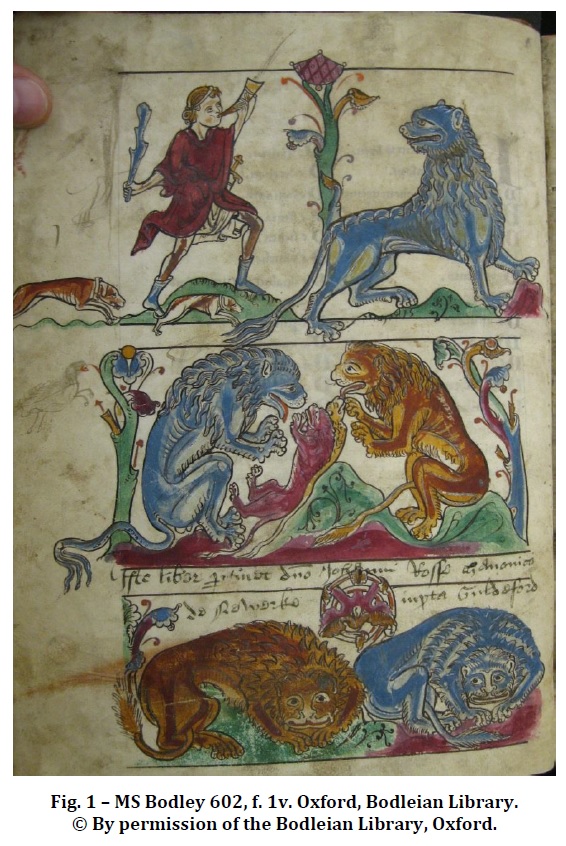

As most bestiaries begin with the chapter on the lion, let us consider the varied representations of the lion to examine how an artist works with a text. This chapter always discusses three main characteristic properties (naturas) of the lion. That in itself is exceptional, since most canonical illustrations focus on a single trait. The chapter on the lion is a rare example (along with a very few others) of having often more than one property illustrated. A good representation of these traits can be seen in the image from Oxford, Bodl. Lib., MS Bodl. 602 (Fig. 1 ). The first of the main attributes is that the lion erases its tracks with its sweeping tail to escape from a pursuing hunter, the second is that it sleeps with its eyes open, and the third is that the lion cub is born dead but is revived on the third day by its father who breathes into its face, which is seen as an allegory for Christ[22]. Three other, secondary traits are attributed to the lion in the text of the chapter: it is afraid of a white cock, it permits men who prostrate themselves to depart in safety, and when sick it can cure itself by eating a monkey. Only a few bestiaries illustrate all or some of these traits[23].

A number of reasons could account for the traditional focus on the main three traits: this particular artist may have been following an earlier model (the artists in two versions of the Latin Physiologus illustrate all three activities), or he may have been limited in the number of illustrations he could draw. These reasons could also explain why some bestiaries ignore most of the textual activities and simply portray a standing lion (sometimes wearing a crown)[24].

In the bestiaries of the Third Family a story about Androcles appears, without any precedent in the bestiary tradition. Androcles was a runaway Roman slave who found shelter in a lion’s den and helped an injured lion by removing a thorn from its paw. Androcles was later caught and condemned to be devoured by lions in the Coliseum as punishment for running away. Fortunately, the lion chosen for the show turned out to be his old friend, and Androcles was saved. An artist noticed the presence of a long and interesting story in the chapter and decided to illustrate it. He replaced the traditional scene of the lion cub with an illustration of Androcles and the lion. He seemed to be free as no canon regarding how to illustrate Androcles story stood at his way[25].

2.3. Biblical motifs in illustrations

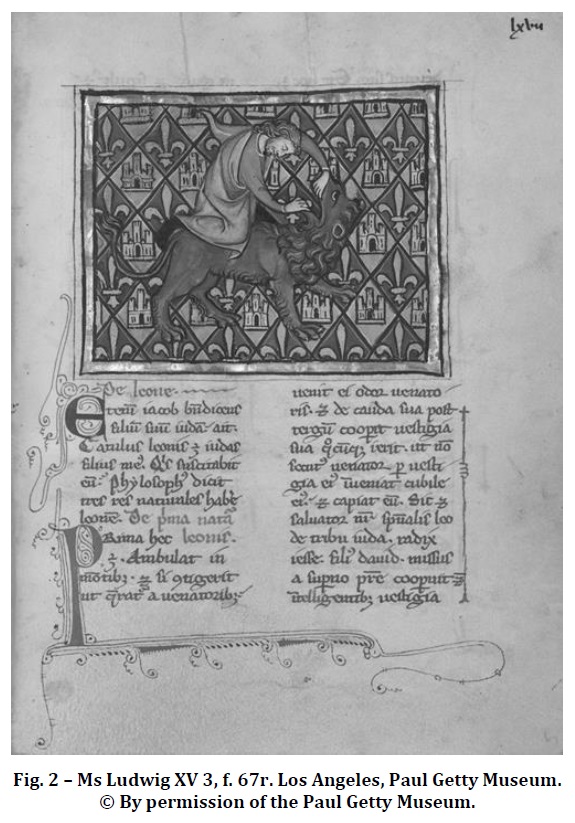

Two of the bestiaries of the BIs Family (Getty Museum, MSS Ludwig XV3 and XV4) omit two of the main traits - the images of the lion covering its tracks with its tail and sleeping with its eyes open, - replacing these with a scene of Samson wrestling a lion (Fig. 2). The third main trait appears as the second image of the chapter in a standard bestiary scene with a lion and lioness near the cub. While it is theoretically possible that artists of the Getty MSS used a corrupted model manuscript in which the first two scenes were absent, it seems illogical, especially as I am not aware of any other models that were altered so significantly[26]. It seems more reasonable to assume that the Biblical story of Samson[27] was the artist’s strongest literary association with the lion and that he used the sequence of the two images to exhibit the paradigm of Death and Resurrection; or perhaps the figure of Samson was used as a prefiguration of Christ, in which case the sequence of the two images would symbolize the prefiguration and the reality prefigured. This explanation makes sense once we consider that the Bible, and Biblical stories and motifs, formed a significant - if not dominant - part of the iconographic tradition accessible to the authors.

The same allusion to biblical subjects is evident in two other illustrations that are exceptional in bestiaries. The first one occurs in a chapter on the whale, or aspidochelone, in a Second Family bestiary (Paris, BNF MS Lat. 6838B, f. 36v)[28]. The aspidochelone, the text says, is so huge that sailors sometimes mistake it for an island and land on it. The standard representation of the aspidochelone is a whale carrying a ship filled with sailors on its back. This is a very old, canonical scene that appears in most bestiary manuscripts[29]. Apparently, the scribe who wrote the manuscript intended that this scene be illustrated, as the space he left for the scene is much bigger than that occupied by the current illustration. But the artist (in this case we can be almost sure that the scribe and the artist were not the same person) solved the problem differently. It is difficult to say why the artist opted for an illustration of Jonah and the whale. It is likely that this was his most striking association with literary whales, just as the Biblical story of Samson occurred most readily to his colleague, as discussed earlier[30].

2.4. Texts and deviations

However, another possibility is that, after reading the text carefully, the artist discovered in it the one-line reference to the story of Jonah[31]. At first glance, this would seem to run counter to the conventional notion that illustrators of manuscripts did not typically read the underlying text (at least, not very closely), instead drawing their inspiration from an established pictorial canon. However, there are several instances that support this theory.

For example, the juvencus, described as a ferocious animal that helps people cultivate land, generally is portrayed as a simple bullock. But in one Second Family bestiary of fairly modest artistic quality (London, BL MS Sloane 3544 f.17r), the stand-alone bullock is replaced by an image of three priests bringing a bullock to the altar[32]. Here, the substitution also seems attributable to a careful reading of the text in which the subject of sacrifice is mentioned: “(...) because among the Gentiles everywhere the bullock was always sacrificed to Jupiter, and never the bull, for in victims the age was also a factor”[33].

Emphasizing a short passage of the text can also be the result of the artist’s desire to illustrate a scene that is unique and controversial or bizarre. Thus, the artist of one Second Family bestiary (Paris, BNF MS Lat. 11207, f. 5) focuses on the single line occurring in the text about the hyena that describes the origins of the creature crocote[34]: “In the region of Ethiopia [the hyena] copulates with the lioness, whence is born a monster named crocote”[35].

Similarly, changes in the standard representation of the unicorn (the most famous of all bestiary characters) can be most plausibly attributed to a careful reading of the text by the artists[36]. In the text below, the unicorn is clearly captured and is not killed:

“The unicorn, which is also called rhinoceros by the Greeks, has this nature: a small animal and similar to a kid, very fierce, having one horn in the middle of the forehead, and no hunter is able to capture it. But by this series of events it is captured: a virgin girl is led to where it lives, and is left there alone in the woods. And as soon as [the unicorn] sees her it leaps into her lap and embraces her, and thus, it is seized”[37].

Most bestiaries, contrary to the text, depict the killing of the unicorn. Only a few exceptions exist[38], and these are certainly due to the fact that the artists carefully examined the text.

2.5. Textual deviations vs. pictorial deviations

Most of the bestiaries showing deviations in their illustrations also contain deviations in the text: for instance, MSS BL Royal 12 F xiii, BL Sloane 3544, BNF 6838B and 11207, Gonville and Caius College, Ms 372/621, Bodl. Lib., MS Douce 88 (I) and (II), Corpus Christi College, MS 53, etc. Most of these manuscripts, except BL Royal 12 F xiii and Corpus Christi College, MS 53, are not masterpieces from the artistic point of view, and because of it at least in some cases we can assume that the scribe served also as the illustrator.

Some artists read the text and offered an interpretation of it. For example, some bestiaries include a chapter on the Perindens Tree. It grows in India, its fruits are sweet, and the dragon fears to approach the tree. The doves gather in its branches because they are safe there. If they fall to the ground, the dragon - which is, of course, a representation of the Devil - devours them. Most bestiaries show the dragon lying under the tree[39]. But in two manuscripts, the image of the dragon is replaced by that of the Devil, in other words an artist maximally facilitated an interpretation of the dragon for the readers[40].

Similarly, one bestiary of the so-called Second D Family London, BL MS Royal 12 F xiii, f. 29r contains a unique and very peculiar scene illustrating the chapter on the wolf[41]. This chapter, which has no counterpart in the Latin Physiologus or in the BIs Family, is quite long and attributes various activities to the wolf in keeping with its rapacious and blood-thirsty nature. There was no established canon governing the representations of wolves, which probably is the reason most artists opted to draw the wolf doing what it was best known for in real life: attacking sheep. Usually this chapter is illustrated by an image of a wolf approaching the sheep fold. However, the attention of the illustrator of the Royal manuscript was captured by the following passage: “The nature of [the wolf] is such that if it sees a man first, it takes away his voice, and as vanquisher of the stolen voice, it reviles [the man]. If [the wolf] perceives that it is seen [first], it lays aside its ferocity and cannot run”[42].

The wolf, of course, symbolizes the Devil, the man represents sin, while the stones are understood to be apostles, other saints, or Jesus Christ:

“Now what is to be done for the man from whom the Devil took away the ability to shout, who cannot cry aloud, who loses the aid of someone at a distance? But what might he do? Let the man lay aside his clothing to be trampled by his feet, taking in his hands two stones, which he strikes one against the other. What next? The wolf, losing the audacity afforded by strength, flees. But the man, secure in his own innate ability, will be free, as he was originally”[43].

The artist drew a half-naked speechless man who takes off his shirt and steps on it, holding stones in his hands.

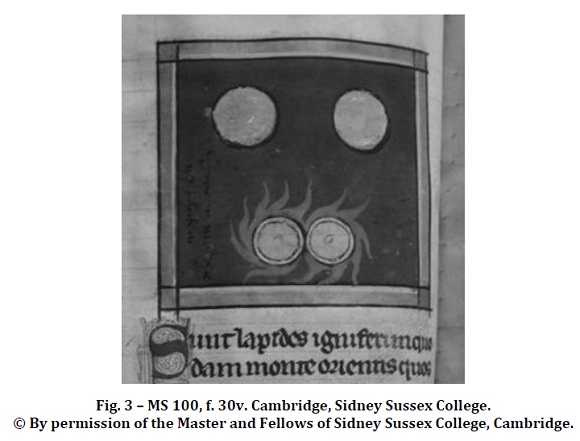

In two bestiaries of the H Family (Cambridge, Sidney Sussex College, MS 100, f. 30v and Chalon-sur-Saône, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 14, f. 85r), artists deviate markedly from the pictorial canon in their representation of the scene on fire stones (lapides Igniferi). According to the text, there are stones in the East that are male and female. As long as they are far apart, there is no fire, but the moment a female stone approaches a male, an all-consuming fire is kindled.[44] Most of the bestiaries portray male and female torsos emerging from the flames.

However, the illustrator of the Sidney Sussex College and the Chalon-sur-Saône manuscripts drew two pictures: one in which the stones are separated, and another where the stones are brought together. This way readers could easily get two discussed situations depicted at the one scene (Fig. 3)[45]. An artist of an H-type BIs manuscript (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 22) went even further. He decided to illustrate only the text of the moralization, which reads: “For there are angels of Satan who forever assail the righteous, not only holy men, but also chaste women. Indeed, Samson and Joseph were both tempted by women; the one triumphed, the other was conquered. Eve and Susanna were tempted; the latter triumphed, the former was conquered”[46].

As a result, the illustration to this chapter does not show any stones at all but instead portrays the two pairs of people mentioned in the moralization: Samson and Joseph, and Eve and Susanna.

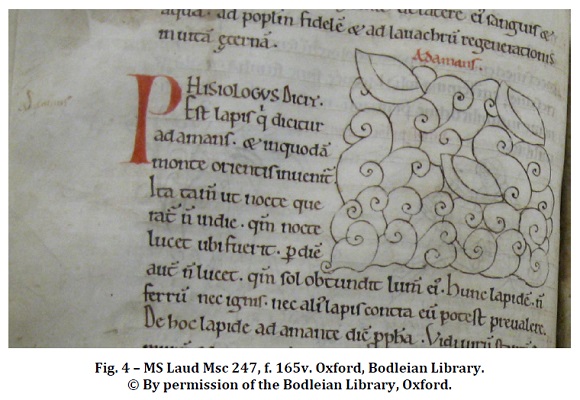

Some chapters appear only in a few manuscripts, as in the chapter on the diamond (adamas), which is found only in the BIs and H Families[47]. The text says that the diamond dwells within a certain mountain at the East, and that it shines only by night. The moralitas contains a quotation from the Septuagint version of Amos 7:7: “I saw a man standing on a wall of adamant and in his hand was an adamant stone in the midst of the people of Israel”[48].

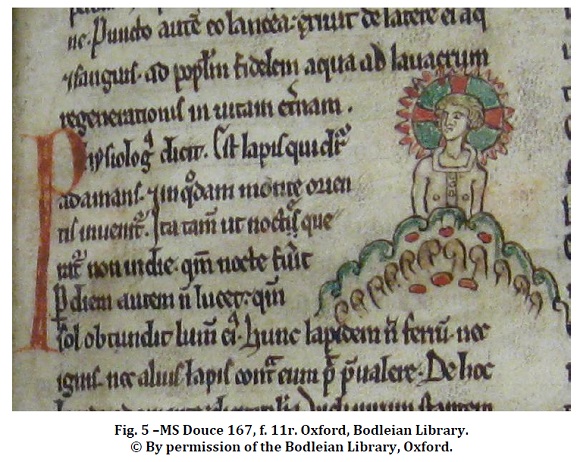

In the text of the bestiary, the diamond represents Christ, while the Eastern mountain is God. Different bestiaries represent this scene in a wide variety of ways. In some, the diamond simply lies on top of the mountain as it is the case in the BIs bestiary - Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Laud Msc 247 (Fig. 4) while in others, the diamond is absent. Some images show the sun with emanating rays while others show no sun at all. Sometimes Christ appears in the midst of the people of Israel, as it is a case in the BIs bestiary Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 167 (Fig. 5)[49]. In one H Family bestiary (Paris, BNF, MS lat. 14429, f. 117r), the passage is illustrated with a figure of a man who is looking for the stone[50].

2.6. Sui generis deviations

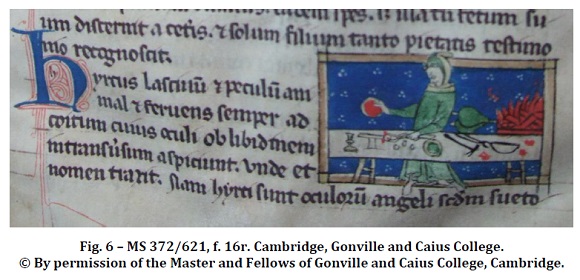

There are, of course, deviations that are, as it were, sui generis - those that cannot be attributed to any of the reasons mentioned above but appear to be the result of the illustrator’s own independent artistic choice. One such unique deviation appears in the so-called Second A Family bestiary (Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College, MS 372/621, f. 16r) in a chapter on the goat (hircus) (Fig. 6). The text reads: “The he-goat is a wanton animal given to butting, and always burning for coitus… The goat's nature is indeed very fiery, so that his blood alone dissolves an adamant stone [diamond], which substance neither fire nor iron can conquer”[51].

Although most artists illustrate this passage by simply portraying a bearded goat with horns, the illustrator of the Caius manuscript depicts a real alchemist’s laboratory with its tools - a flask, a horn, tongs, a hammer - and shows his unsuccessful attempts to dissolve adamant. Ironically, no goat is present in the picture, as if it is not needed at all, since an artist seemed to have only been interested in the wonderful properties of the diamond. In this case the deviation could be compared to that in the previously mentioned bestiary e Musaeo 136, where the illustration to the chapter on the tigress does not show a tigress.

2.7. LONDON, BL MS SLOANE 3544

Out of about the sixty illustrated bestiaries, about twenty, that is, roughly one-third, contain deviations. In total these deviations numbers no more than thirty. Most of them contain only one or two, although some manuscripts contain more deviations than do others. The champion in this regard is certainly the Sloane bestiary, a Second Family manuscript (London, BL MS Sloane 3544), which contains seven deviations.[52] The first one occurs in the chapter on the manticora, a mythical beast that loves to eat human flesh[53]. Usually the manticora is depicted alone. However, the illustrator of the Sloane bestiary chose a passage discussing the medicinal properties of manticora dung and illustrated it by portraying a woman collecting the dung (f. 11r).

The second deviation appears in the chapter on the phoenix, the famously long-lived bird that is cyclically reborn. The phoenix collects twigs and sets itself on fire in order to resurrect[54]. There are several ways to illustrate this chapter in bestiaries, but, except for two, none of the pictures contains people. The first exception occurs in the Sloane manuscript, f. 27r, where a seated, bearded man in a long robe appears to the left of a phoenix. It is certainly intended to illustrate a passage of the chapter that reads: “Who, therefore, announces to <the phoenix> the day of its death, so that it may make the covering for itself and fill it with delicate spices, and enter into it and die there, where the stench of death can be overcome by sweet spices[55]?”

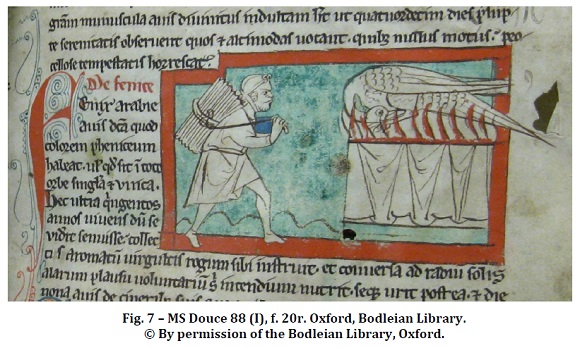

The second exception appears in the phoenix scene in the Second Family bestiary (Oxford, Bodleian Lib., MS Douce 88 (I), f. 20r), which shows a man gathering twigs. (Fig. 7). The third deviation appears in the chapter on the sweet-singing nightingale (f. 30r)[56]. Most bestiaries show one bird, but the Sloane manuscript illustrates three people enjoying its singing.

In addition to these three deviations, the Sloane also contains three other unusual images that appear in the chapters on the serpents scitalis, dipsa and salamandra (ff. 38r, 39r). In each of the scenes, the artist added human figures: three men in the scene with the scitalis and dipsa and two in the scene with the salamandra. As in the example with the phoenix discussed above, this clearly shows the influence of a close reading of the text[57].

In fact, my review of all extant Latin bestiary images has shown that virtually all significant deviations from the accepted pictorial canon (with the exception of images of stags, see note xxxv) contain human figures. I believe this finding to be of major importance. Given that bestiaries are books of creatures, and that most bestiary illustrations result from following a pictorial tradition, those few images that evidence a close and thoughtful reading of the text especially deserve our close attention, as their deviations from the canon may be presumed to be intentional, revealing something of the mind of the artists that produced them. In this case, adding human figures to images of beasts or objects suggests that for those artists who brought an independent thought to their work, the primary interest of the bestiary was man and not beast. In my recent article[58] analyzing captions and long rubrics in various bestiary chapters, I concluded that most attention was paid to the scenes where a human figure was included. That conclusion is now corroborated by this research.

The above analysis of sixty bestiary manuscripts containing approximately five thousand images demonstrates that the bestiary was a very conservative genre, in which the canon of tradition played a dominant role. Indeed, roughly one-third of illustrated bestiaries contain no more than thirty deviations, and in the majority of cases there are only one or two deviations per manuscript. Deviation therefore occurs in less than in one percent of the images. There seems to be no connection between the country of origin, bestiary family, and century of the manuscript on the one hand, and the possibility that a deviation will occur on the other. The deviation can also appear in any section of the bestiaries and in a chapter of any length. This indicates that deviation is an individual artistic choice.

After analyzing the entire corpus of images, we can postulate that most of the deviations from the established pictorial canon were due to a careful reading of the text of the chapter, as in the chapters on the bullock, aspis, phoenix, wolf, goat, fire stones and others. Most of the bestiaries with deviations in their illustrations also contain deviations in the text. Moreover, most of these manuscripts show only moderate artistic merit, suggesting that - at least in some cases - the writing and the illustrations were produced by the same hand.

Other reasons for deviations are rare. Sometimes a standard image may be replaced by another because of a strong biblical influence (as in the case of the lion and whale), which in turn proves that the text is the most important source of the influence on an image. Other cases of deviations (as for instance, the scenes with man at the elephant chapters in Bodl. Lib. MSS Douce 88) are sporadic.

Finally, as stated above, the evidence shows that in most, if not all cases, the deviations occur when the artist chooses to incorporate a human figure. In other words, even in bestiaries - books of beasts - the main figure is not a beast but a human being.

The above conclusions can certainly have further important implications. There is no reason to suggest that deviations of images in other, closely related genres of medieval manuscripts - such as the aviaries, or the vernacular bestiaries and encyclopedias -, work differently. The corpus of images in these genres extends to several thousands, and because of this volume, the building of statistics similar to those presented here would be a much larger undertaking. Until such statistics are available, the observations based on the bestiaries made here can stand as a working hypothesis.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BRODEUR, Arthur G. - “The Grateful Lion”. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 39 (1924), pp. 485-524. [ Links ]

BROWN, Arthur C. - “The Knight of the Lion”. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 20 (1905), pp. 673-706. [ Links ]

CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-Family Bestiary. Commentary, Art, Text and Translation, Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006. [ Links ]

CURLEY, Michael - Physiologus: A Medieval Book of Nature Lore. Chicago and London: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1979. [ Links ]

DINES, llya - “The Hare and its Alter Ego in the Middle Ages”. Reinardus: Yearbook of the International Reynard Society 17 (2004), pp. 73-84. [ Links ]

DINES, Ilya - “The Problem of the Transitional Family of Bestiaries”. Reinardus: Yearbook of the International Reynard Society (2013), pp. 29-52. [ Links ]

DINES, Ilya - “Between Image and Text: The Long Rubrics and Captions in Medieval Bestiaries”. Frühmittelalterliche Studien 49.1 (2015), pp. 149-164. [ Links ]

DRUCE, George Claridge - ‘’The Caladrius and its legend, sculptured upon the twelfth-century doorway of Alne Church, Yorkshire”. Archaeological Journal 69 (1912), pp. 381-416. [ Links ]

DRUCE, George Claridge - “The Elephant in Medieval Legend and Art”. The Journal of the British Archaeological Association 76 (1919), pp. 1-73. [ Links ]

DRUCE, George Claridge - “The Lion and Cubs in the Cloisters’’. Canterbury Cathedral Chronicle 23 (1936), pp. 18-22. [ Links ]

GEORGE, Wilma and YAPP, Brunsdon - The naming of the Beasts: Natural History in the Medieval Bestiary. London: Duckworth, 1991. [ Links ]

JAMES, Montague Rhodes - The Bestiary: a reproduction in full of MS Ii. 4.26 in the University Library, Cambridge. Oxford: Roxburghe Club, 1928. [ Links ]

MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1962. [ Links ]

MCCULLOCH, Florence - ‘’Le Tigre et le miroir. La vie d’une image, de Pline à Pierre Gringoire’’. Revue des Sciences Humaines 33 (1968), pp. 149-160. [ Links ]

YAPP, Brunsdon - “A New Look at English Bestiaries”. Medium Aevum 54 (1985), pp. 1-19. [ Links ]

Como citar este artigo | How to quote this article:

DINES, Ilya - “Producing the Bestiary: From Text to Image”. Medievalista 29 (Janeiro - Junho 2021), pp. 91-116. Disponível em https://medievalista.iem.fcsh.unl.pt.

Data recepção do artigo / Received for publication: 29 de Novembro de 2019.

Data aceitação do artigo / Accepted in revised form: 5 de Junho de 2020.

[1] Regarding the history of the Physiologus see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1962, pp. 15-44.

[2] The earliest manuscript is Bern, Burgerbibliothek, MS 611.

[3] Bern, Burgerbibliothek, MS 318 and Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, MS 10066-77.

[4] This is the 10th-11th century New York, The Morgan Library and Museum, MS M 397.

[5] See JAMES, Montague Rhodes - The Bestiary: a reproduction in full of MS Ii. 4.26 in the University Library, Cambridge. Oxford: Roxburghe Club, 1928; MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 28-40; YAPP, Brunsdon - “A New Look at English Bestiaries”. Medium Aevum 54 (1985), pp. 1-19; DINES, Ilya - “The Problem of the Transitional Family of Bestiaries”. Reinardus: Yearbook of the International Reynard Society (2013), pp. 29-52.

[6] The manuscripts of French bestiaries as well as Physiologi of the so-called Dicta Chrysostomi are beyond the scope of this research.

[7] The deviations as a subject were first discussed in the entries dealing with various species in MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, as well as in GEORGE, Wilma and YAPP, Brunsdon - The naming of the Beasts: Natural History in the Medieval Bestiary. London: Duckworth, 1991.

[8] For more detail see DINES, llya - “The Hare and its Alter Ego in the Middle Ages”. Reinardus: Yearbook of the International Reynard Society 17 (2004), pp. 73-84. The only scene where a deviation relevant to our discussion appears is in London, BL MS Royal 12 F xiii, f. 34v. In this scene, in addition to standard representation of Adam and animals, there appears another anonymous person placed on the back of a camel.

[9] See DINES, Ilya - “Between Image and Text: The Long Rubrics and Captions in Medieval Bestiaries”. Frühmittelalterliche Studien 49.1 (2015), pp. 154-155, discussing various representations of the aspis. Another very curious exception is found in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 22, f. 168r, where there is a scene with two strange aspides that look rather like dogs. At the left, one aspis is shown jumping upon a man, which probably illustrates the lines saying that the creature runs with an open mouth and has a venomous bite; at the right, another doglike aspis bites Cleopatra thus illustrating the passage dealing with a famous story about her suicide. The images of the two Corpus Christi College bestiaries (CCC22 and 53) are online. [Accessed 24 February 2020]. Available at https://parker.stanford.edu/parker?q=.

[10] Copenhagen, Kongelige Bibl., MS Gl. kgl. S. 1633 4º, f. 16r and Cambridge, Univ. Lib., MS Gg. 6.5, f. 21v. The images of the Copenhagen bestiary are online. [Accessed 24 February 2020]. Available at http://www5.kb.dk/permalink/2006/manus/221/eng/. For details about the fox in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 119-120.

[11] London, BL MS Harley 4751, f. 27r. The images of this bestiary are online at bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=8797. For details about the horse in bestiaries, see McCulloch, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 127-128.

[12] London, BL MS Haley 3244, f. 48v. The images of this bestiary are online. [Accessed 24 February 2020]. Available at https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=8798. For details about the donkey in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, p. 92.

[13] London, BL MS Harley 4751, f. 25r.

[14] London, BL MS Royal 12 F xiii, f. 39r. The images of this bestiary are online. [Accessed 24 February 2020]. Available at https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=95.

[15] For details about the bull in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, p. 148.

[16] For details about the boar in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 97-98.

[17] For details about the dromedary in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, p. 113.

[18] For details about the caladrius in bestiaries, see DRUCE, George Claridge - ‘’The Caladrius and its legend, sculptured upon the twelfth-century doorway of Alne Church, Yorkshire”. Archaeological Journal 69 (1912), pp. 381-416.

[19] For instance, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 22, f. 63v and Cambridge, Univ. Lib., MS Ii 4. 26, f. 4v. For details about the panther in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 148-150.

[20] For discussion of the tiger in bestiaries see MCCULLOCH, Florence - ‘’Le Tigre et le miroir. La vie d’une image, de Pline à Pierre Gringoire’’. Revue des Sciences Humaines 33 (1968), pp. 149-160.

[21] An image can be found online. [Accessed 24 February 2020]. Available at https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/inquire/Discover/Search/#/?p=c+2,t+bodley%20533,rsrs+0,rsps+100,fa+,so+ox%3Asort%5Easc,scids+,pid+,vi+.

[22] For details about the lion in bestiaries, see DRUCE, George Claridge - “The Lion and Cubs in the Cloisters’’. Canterbury Cathedral Chronicle 23 (1936), pp. 18-22.

[23] Oxford, Bodl. Lib., MS Douce 167, f. 1r; Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 53, f. 189r; Cambridge Univ. Lib., MS Ii 4. 26, ff.1rv ; Oxford, Bodl. Lib., MS 764, ff. 2rv ;Valenciennes, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 101, f. 189r.

[24] London, BL MS Harley 3244, f. 36r and Hague, Rijksmuseum Meermanno-Westreenianum, MS 10 B 25, f. 1r.

[25] On the Androcles story, see BROWN, Arthur C. - “The Knight of the Lion”. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 20 (1905), pp. 673-706; BRODEUR, Arthur G. - “The Grateful Lion”. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 39 (1924), pp. 485-524.

[26] The unique example in which only the third scene appears is the H Family manuscript Paris, BNF, MS Lat. 3638, f. 60r.

[27] Judges, 16.

[28] The images of the bestiary are online. [Accessed 24 February 2020]. Available at http://mandragore.bnf.fr/jsp/switch.jsp?division=Mix&cote=Latin+6838+B.

[29] For details about the aspidochelone in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 91-92.

[30] Given what we know about the rest of the canon, I do not think it is worth suggesting that the model bestiary an artist used did not have a scene with a whale.

[31] Jonah 1-2.

[32] The images of the bestiary are online. [Accessed 24 February 2020]. Available at https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=6510.

[33] See CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-Family Bestiary. Commentary, Art, Text and Translation, Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006, p. 152.

[34] The images of the bestiary are online. [Accessed 24 February 2020]. Available at mandragore.bnf.fr/jsp/rechercheExperte.jsp.

[35] From CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts …, p. 132. Another example where a minor but curious trait can inspire an artist to deviate from a conventional representation can be seen in the chapter on the stag. Instead of the usual illustration of a stag attacking its enemy-snake, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 53, f. 192r illustrates a passage that discusses the way stags help each other cross the river. The same motif is also illustrated in the Third Family bestiaries Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 254, f. 10r, and in Cambridge, Univ. Lib., MS KK 4 25, f. 56r.

[36] For details about the unicorn in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 179-183.

[37] From CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts …, p. 126.

[38] For example, Oxford, Bodl. Lib., MS Douce 167, f. 4v.

[39] For details about the Perindens tree in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 157-158.

[40] Paris, BNF MS Lat. 11207, f. 31v, and Lat. 6838B, f. 30v.

[41] For details about the wolf in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 188-189.

[42] From CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts …, p. 143.

[43] From CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts …, p. 144.

[44] For details about the fire stones in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, p. 119.

[45] The image in the Chalon-sur-Saône MS is virtually identical, suggesting either that the artist followed the model of the Sidney Sussex MS or that both of them followed another manuscript that is no longer extant.

[46] From CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts …, p. 220.

[47] For details about the diamond in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 109-110.

[48] From CURLEY, Michael - Physiologus: A Medieval Book of Nature Lore. Chicago and London: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1979, p. 62.

[49] A similar situation occurs with illustrations to the chapter on elephants. The text of the chapter is one of the longest in the entire bestiary tradition and contains numerous traits. As a result, various bestiary families starting from the BIs tend to illustrate their own favorite motifs. The most significant deviations are the following: Oxford, Bodl. Lib. MS Douce 88 (I), f. 8r portrays a man who feeds an elephant. MS Douce 88 (II), f. 87v contains images typical of the Second and Third Family bestiaries, showing an elephant carrying a castle filled with soldiers on its back, as well as a marginal drawing at the same level as the main illustration that displays a man holding a shield and a palm branch, who may represent the soldiers’ enemy. Neither deviation appears to be based on the text. For details about the elephant in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 115-19, and DRUCE, George Claridge - “The Elephant in Medieval Legend and Art”. The Journal of the British Archaeological Association 76 (1919), pp. 1-73.

[50] The images of this bestiary are online at http://mandragore.bnf.fr/jsp/switch.jsp?division=Mix&cote=Latin+14429+%5bff.+96-118%5d.

[51] From CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts …, p. 152.

[52] The images of Sloane bestiary are online at https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=6510.

[53] For details about the manticora in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 142-143.

[54] For details about the phoenix in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, pp. 158-160.

[55] CLARK, Willene B. - A Medieval Book of Beasts …, p. 176.

[56] For details about the nightingale in bestiaries, see MCCULLOCH, Florence - Medieval Latin and French…, p. 144.

[57] The man appears to be riding the cocodrillus in Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College, MS 372/621, f. 11r; Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 53, f. 207r contains people in the scene of the serpents, the man fights the basilisk in London, BL MS Harley 3244, f. 59v and in Getty MS 100, f. 49v. The images of Getty MS 100 bestiary are online at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/240115/unknown-maker-northumberland-bestiary-english-about-1250-1260/. All these scenes are based on the text.

[58] DINES, Ilya - “Between Image and Text: The Long Rubrics and Captions in Medieval Bestiaries”. Frühmittelalterliche Studien 49.1 (2015), pp. 149-164.