Introduction - research questions, methodology, and article structure

In previous studies of the dragon in Old Norse (ON) sagas and þættir, I have often felt the need for more solid, quantifiable notions of what kind of places dragons are associated with, and in what way do they relate to them. As such, in the present article1, I endeavoured to analyse the relationship of dragons with the environments they inhabit in these prose narratives. To do so, I first mapped the landscapes inhabited by dragons, as well as weather phenomena, times of day, and seasons most associated with their presence. Considering the potential interest of these results for further study of saga dragons, in the first and largest part of this article I will devote myself to presenting the conclusions that I arrived at, considering them quantitatively and discussing them. In a second, shorter part of the article, I will close off with some brief notes on how a dragon’s presence affects the natural environment, through the sagas where that is manifest. Dragons interact with the landscape usually in a destructive way, and their presence tends to lead towards those spaces being turned into non-shared spaces, dominated by the dragon.

For the purpose of accomplishing the abovementioned goals, I conducted a wide source-survey, isolating fifty-five dragon references across thirty-eight texts - as several of the texts I studied contain more than one dragon - ranging in composition date from the 13th to the 15th centuries. The episodes are highly varied in detail2. I did not focus on geographical or toponymical data, merely on accounting for the physical features of landscapes and places that dragons interact with or inhabit. My corpus3 is comprised majorly of sagas belonging, although not solely, to the genres4 of legendary sagas (fornaldarsögur) and chivalric sagas (riddarasögur), both translated and indigenous ones - by far, those two saga genres hoard almost of the dragons in ON literature. Considerations about saga genres regarding the landscape distribution will also be pointed out when useful.

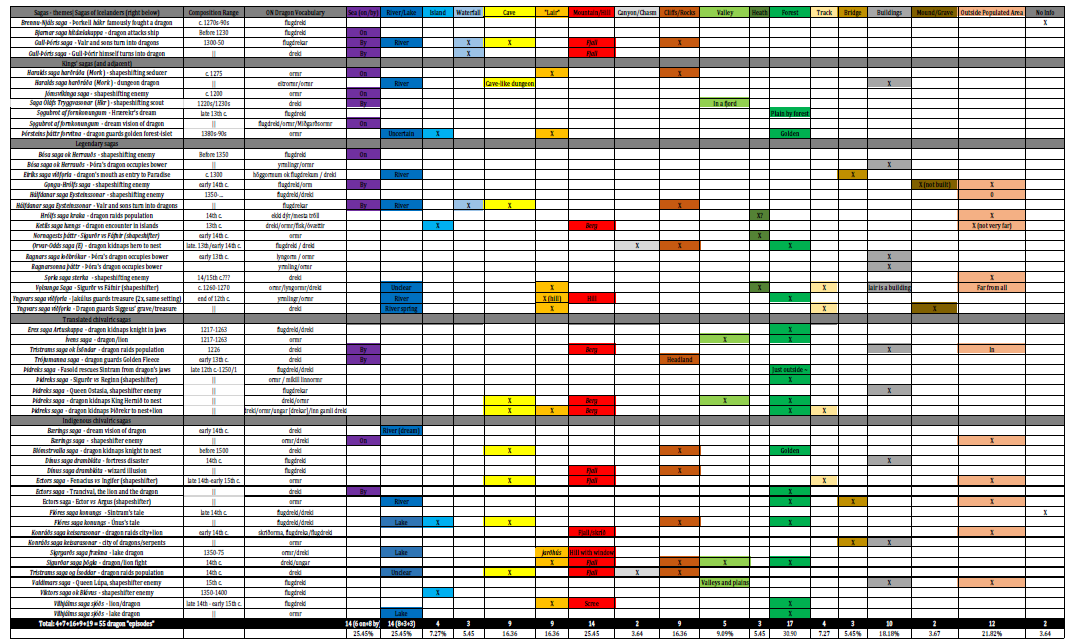

Regarding my initial search, I paid attention to descriptions of environments surrounding the dragons, not only to the places they inhabit, but also those that they visit - or, more usually, that they attack - and those where they are killed and/or laid to rest, as sometimes those are all different settings. I noted down topographical elements present in the places where dragons roam, as well as whether they are placed in the wild or close to inhabited places, in an attempt to find tendencies or lack thereof - this data will be presented through a table at the end of the article (Table 1). On a parallel search, I also took note of whether dragons were, as well as of what time of the year and what type of weather and lighting conditions they made their appearances, whenever they were specified. This information was limited and much less frequent in the sources, which is why it will be debated in the text but not presented on the table.

The question of where dragons begin and end in ON literature also lends itself to a lengthy answer. The usual vocabulary for them encompasses the words ormr (pl. ormar) and dreki (pl. drekar). Dreki would seem to lend itself to less debate, as it refers without fault to a concept of “dragon” as we tend to think of it now: it usually designates a serpent with unusual physical characteristics (wings, breathing fire, abnormally large size) or which assumes a significant, and usually typified, narrative function5. Ormr is a more problematic term since it is applied both to commonly sized snakes as to the creatures to which the label “dragon” is fitting above all others, such as Fáfnir of the Vǫlsung legend. I chose to include those ormar in this study (aside from those which are also called drekar) which corresponded to the above-outlined characteristics of the dragon, either physical or narrative. As Santiago Barreiro defends, “dragon” can be understood more in terms of behaviour than of taxonomy6. Moreover, Ármann Jakobsson has brought attention to how supernatural beings in medieval literature do not lend themselves to an easily deployed Linnean categorization, since medieval terminology is seemingly used without following a set of rules7. It is my view that a dragon can be called as such, by us that study it, if both its description and the surrounding narrative context fit with the criteria listed above, even if the text directly refers to it only by the words dýr (“beast”) or trǫll8.

Mapping draconic landscapes

Terms of inquiry and general results

I want to lead off my discussion of the environments connected to dragons by explaining the types of landscape elements that I tallied, which will be discussed and divided into broad groups. The specific vocabulary in ON varied, but its complete listing would fall here outside the mark - I will make a point of mentioning cases where the possibility of several interpretations could be relevant9. Firstly, then, the landscape elements connected to water: “sea”, “rivers/lakes”, “islands” and “waterfalls”. Secondly, several elements of topography that seemed connected to geological accidents: on one end, mountains/hills, canyons/chasms, and cliffs/boulders; on the other, caves and "lairs"10, the last term being a more nebulous classification regarding whether it is manmade or a "natural" landscape feature - the latter seems to be the case most of the time, with "lair" being used as if to mean an underground dwelling such as a cave, but we I believe it important to keep the nuances in mind (in Vǫlsunga saga, for example, walls and iron-doors are mentioned for the dragon‘s lair, which is described as a "hús" ["house"], even if its “stokkar” [“beams”] are said to be “grafit í jǫrð niðr” (“ buried down into the earth”)11. A third category may be called “greener”, so to say, as it seems connected to a more abundant reference to vegetation, under which we find forests, valleys, and heaths/moors. Among these, if anywhere, I would adjoin "tracks" as well - these are not human paths, but those carved by dragons through their movement, usually in the middle of the natural landscape. Finally, a listing of manmade locations: bridges, buildings (either a single building or a group of buildings), mounds, and mentions of dragons relative to populated areas (both far and near). Only two of the analysed texts simply mentioned dragon fights within the narrative without ascribing them any physical context12.

The above are the totality of landscapes features that I found associated with dragon narratives in the analysed texts, in generic terms. A full table with the information about which landscapes appear in which sagas can be found at the end of the article (Table 1), further broken down by saga genre13. I will now discuss the tendencies found as a result of this survey and some possible interpretations for these results14.

To start off, we can note that the landscape elements most abundantly connected to dragons15, by percentage of appearances in episodes relative to the total number of episodes, are: forests (c. 31%), the sea (c. 25% of narratives), lakes/rivers (c. 25%), mountains/hills (c. 25%), buildings (c. 18%), cliffs/boulders (c. 16%), caves (c. 16%), and lairs (c. 16%). In some instances, it would perhaps be more useful to consider the categories mentioned above as tallied together. We will now move into a detailed discussion of the aqueous places where dragons are found.

Aquatic environments

Be it at sea or in a body of freshwater, there is a significant association of water with dragons. I would add the detail that ten out of fourteen texts which mention the sea are set in Scandinavian geography. However, we should take care with the notion that the sea would be a natural habitat for a dragon, or that these dragons should be thought of as "sea dragons"16, which could be suggested by the existence of the mythological Miðgarðsormr, the gigantic serpent which "lies in the midst of the ocean encircling all lands and bites on its own tail”17. If we look at the specifics of the "sea” category, we see that out of all instances, 6 are dragons that either fight on or disappear into the sea; eight instances are of dragons that reside or are fought by the sea. Furthermore, nine out of fourteen dragons are actually shapeshifting men, usually berserkers or sorcerers, who have the ability to transform into dragons or whose fylgja18 is represented by a dragon in a dream.

Freshwater is a somewhat different matter, showing some dragons which appear to live in water, at least partially. We find three mentions of dragons in lakes, and while the dragon of Flóres saga19 simply lives on an island in a lake20, both in Vilhjálms saga sjóðs21 and in Sigrgarðs saga frækna22 these dragons seem at ease in the water, attacking from underwater and happy to continue the fight from the lake. They can be understood, perhaps, to live or at least dwell there habitually, even if in Vilhjálms saga the lake appears to be in the middle of an eyðiskógr, "a desert-forest” in Libialand23, and for Sigrgarðs saga the lake is next to the small hill where the dragon’s lair is. Rivers are far more common, with eight mentions of dragons specifically by rivers of various dimensions (one in a dream and one underground, in a dungeon24). In three instances, the word vatn isn’t accompanied by enough descriptors to allow us to understand which type of body of water is dealt with (whether a stream or a lake is present). Of the analysed sagas, it is in two íslendingasögur ("sagas of Icelanders", which are mostly set in Iceland and Scandinavia), that we see waterfalls associated with dragons, and only in somewhat specific Northern geographies. One is in the north of Norway, as the saga tells us that a river falls from a mountain called Blesavergr (on the coast of Dumshaf), and behind the waterfall is the cave where Valr and his sons rest, shapeshifted into dragons-this cave is known precisely by this, bearing the name Valshellir"25. Another is in Iceland-a waterfall named Gullfoss, in the North of Iceland-where Gull-Þórir himself is said to have near it [“become a dragon and had lain on his gold-chests”]26 ("hafi að dreka orðið og hafi lagist á gullkistur sínar”)27.

Dragons are often mentioned as having the habit of moving to water to drink, and the influence of Fáfnir as a model for other dragon narratives must account for the frequency of this motif - in the Fáfnir legend, in its various forms, the dragon Fáfnir is mentioned has habitually sliding or scurrying along one same path on the way to water, where it goes to drink28. When we consider that Fáfnir is the preeminent ON dragon in legend29, it is a most plausible assumption that the tale of the Vǫlsung dragon-slaying was one of the main contributors for the Old Norse concepts of dragons, and it is easy to understand why so many narratives also adopt most narrative spatial features that characterize Fáfnir - the water, the lair, the isolation from society30.

Curiously, while the treasure of Fáfnir is said to come specifically from a river in Vǫlsunga saga,31 the place where Fáfnir goes to drink is merely referred to as "water"32. If we consider how many episodes associate dragons with aqueous places altogether, then, we arrive at an impressive 51% of episodes. Whether on, under, or by water, the association of dragons with this element can justifiably be considered strong. To my mind, the explanation for this could most probably be understood as a literary impact of the deep-set mythological association of the titanic Miðgarðsormr with the sea, and also in the influence of the Fáfnir-tradition. However, given the great abundance and variety of aquatic spaces, it is curious that dragons do not seem to have an intrinsic symbolic connection to them, nor interact with them in very seemingly significant (except for those dragons which make).

Rocky environments

The same analysis of the data could be made for stony habitats. Only two hills are found, while mountains seem more abundant. However, the exact tally between "mountains/hills" and "cliffs/boulders" is unclear, as one of the words tallied as “mountain”, berg, is liable to multiple interpretations and could mean either a mountain or other elevation, an agglomerate of rocks, or a cliffside33 (in my survey I counted them among the "mountains”, as narrative context seemed to imply an elevation, but this ambiguity should be borne in mind). Additionally, if we count together those "caves" and "lairs" which seem possible to group into underground dwellings of any sort (as most often seems to be the case), they are shown to be an important element of dragon stories: we are looking at c. 31% of dragon narratives with underground dens (seventeen mentions)34. If we consider rocky environments as a whole, we will notice that they represent a very significant tendency in dragon narratives: twenty-four episodes, which amounts to c. 44% of the narratives. The other 56% are mostly split between episodes happening solely in water, forest areas, or populated areas.

“Green” environments

Nevertheless, the clear "winner" in this tally of isolated landscape elements, if there is to be one, is clearly "forest" (skógr), contained in nearly 31% of the episodes as the most common setting for dragon encounters. The abundance of this element is clearly explained by the influence of continental romance in saga narrative and is a good example on which to pivot our discussion towards considerations of landscapes by genres. Chivalric romance literature posits the forest as a preferred space for the knightly quest35, and that will be preserved in both ON translations of romances and in the indigenous romances featuring dragons, highly influenced by the translations (mixing them up with the Norse tradition at points). Six out of the nine episodes from translated material are set in forests (Þiðreks saga alone contributes four of those), and in the indigenous romances, we find that five out of eleven analysed sagas contain at least one dragon in a forest, most of them inspired either in the lion-knight motif from Ívens saga and Þiðreks saga, or the dragon and kidnapped knight motif from Þiðreks saga. For contrast, only two out of sixteen fornaldarsögur episodes also contain a forest: the E-version of Ǫrvar-Odds saga, which depicts a dragon in a forest with younglings36, similar to Þiðreks saga; and Yngvars saga, where Sveinn, the titular hero’s son, comes upon the dragon Jakúlus and we learn that there is a forest by its lair (i.e. a small hill made up of treasure and serpents)37. It should be noted that indigenous riddarasögur is the genre which contains as a whole the most descriptive texts regarding landscape features, thriving on elaborate descriptions of the topography of dragon encounters38. Tracks made by dragons are also usually found in the middle of a forest - two times, plus one more in a heath and another near a city. We will revisit interactions between dragons and forests in the second part of this article.

Valleys (dalar) appear five times in the tally, and in three of those they are forested valleys. In one of the outliers, Valdimars saga, it is mentioned that a fight between armies (including a hostile sorceress shapeshifted into a dragon) happens above the valleys and plains outside the walls of a city39. The other exception, where no skógr is mentioned, comes up in the Heimskringla version of Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar - there, the dragon is the landváttr (“spirit of the land")40 of East Iceland, coming out from the valley of Vápnafjǫrðr to ward off the sorcerer who, shapeshifted into a whale, is scouting the shores of Iceland at the command of king Harald Gormsson, looking, unsuccessfully, for a place where the king could easily invade the island41.

On the other end of the spectrum, some elements are worthy of note for their almost-complete absence. The heath/moor shows up only three times, two of them through the placename Gnitaheiðr42, the place where Fáfnir abides - the element heiðr is an obvious cognate of English “heath” and takes the same meaning43. The remaining heath seems to occur in Hrólfs saga kraka, and isn’t as directly referred to, but it can be surmised from when the champion Bǫðvarr-Bjarki is facing the creature, as he throws the cowering Hǫttr "down into the moss/moorland" ("niðr í mosann").44

Manmade structures and populated areas

There is a considerable number of dragons who choose to make their presence felt in human towns and buildings. These will be enumerated individually, as they are very different episodes. As mentioned above, only once there is a “lair” which is declaredly a building (that of Fáfnir), but other examples exist where the word “lair” is not used. In Haralds saga harðráða, the dragon faced by the king lives in a dungeon45, which, while resembling a cave, is situated within Miklagarðr (Constantinople)46. In Bósa saga, Ragnars saga loðbrókar and Ragnarsonna þáttr47, the same dragon is discussed - the pet of the Þóra, given to her by her father earl Herrauðr, it is kept initially inside a small box, but outgrows it to engulf the whole lady’s bower (the skemma). In translated riddarasögur, the dragon of Tristrams saga recurrently attacks a city, even if it is afterwards slain in the wilderness48; and in Þiðreks saga, the sorcerer-queen Ostasia seems to project herself in dragon-shape to aid her husband, king Hertnið, in an enormous battle which occurs outside their fortress against the forces of king Ísungr, while her human body never leaves the building49. In Dínus saga drambláta, there is an episode where a fortress is suddenly rendered asunder by earthquakes and other natural phenomena, while a dragon suddenly shows up and contributes to the destruction50. Konráðs saga keisarasonar sees the hero find and rob precious gems from a whole ormar-infested city, where a singular, bigger dreki is king. On the way to this city, the hero jumps over some ormar guarding a bridge51. We find two other bridges connected to dragons: one in Ectors saga, regarding the shapeshifter Argus episode52; and another in Eiríks saga víðfǫrla, where a terrifying dragon guards a bridge to Paradise - in a test of faith, the heroes must jump into his gaping maw to reach the Edenic lands they seek53. While not precisely a named landscape element, I would like to note here that c. 22% of the episodes studied mentioned their level of proximity/distance to human settlements. More will be said about this later on, when we discuss the relationships dragons form with several spaces.

"Grave-mound” or “barrow” is only mentioned as a landscape element once by name, in Gǫngu-Hrólfs saga, in the dying words of Grímr Ægir, the nemesis of the hero Hrólfr. This sorcerer had turned into a dragon (but also other animals) during their fight, and, after defeat, expresses his wish that Hrólfr builds a mound overlooking the sea for his body, which he will haunt and pronounce doom over passing sailors; nevertheless, the mound is never built, as his body melts away54. Furthermore, the ambivalent nature of "lairs” (as I tallied them here), should be taken into account. While they are rarely well-described, I encountered at least one instance of a lair that doubles as a grave: in Yngvars saga víðfǫrla, the second dragon‘s lair is later revealed to be the resting place of one king Siggeus, who amassed much gold while alive, and "when he died, he was buried there, where you now saw the dragon“ ("er hann dó, var hann þar grafinn, sem nú sáu þér drekann”)55. Then, it is clarified that his body and that of his greedy daughters were eaten by dragons, but that "some men think that they were turned into dragons” ("en sumir menn ætla, at þau sé at drekum orðin")56 This double presentation of theories on the destiny of the corpses may be an instance of the type of phenomenon that H.R. Ellis Davidson speaks of regarding the Beowulf dragon and the last survivor of the treasure-holding people:

“The account suggests that this is a rationalization of the idea (which would be repugnant to a Christian audience) that the dead man himself became a dragon. It is a familiar idea in Old Norse literature.”57

As Davidson points out, in ON literature, very often men who hold treasures become dragons, especially if they are greedy - sometimes at the end of life, such as Gull-Þórir58. However, aside from Yngvars saga (and the even more oblique idea in Gǫngu-Hrólfs saga), there is a general absence of mentions of mounds as "resting" places for dragons, which reinforces this point in the discussion. Often, parallels are made between Anglo-Saxon dragon notions and ON ones, but Old English literature is much more definite about dragons belonging in mounds: 11th century poem Maxims II pronounces “Draca sceal on hlæwe/ frod, frætwum wlanc” ("The dragon shall dwell in a barrow,/ Old and treasure- proud.") (ll. 26-27)59. It is interesting that sagas seem to ascribe grave mounds mostly to other types of supernatural beings than to dragons60, but the connection of dragons with graves cannot be discounted from Norse culture when we consider that only Eddic dreki, Níðhǫggr. It is spoken of with corpse connections in two instances of Vǫluspá61, for instance. The idea of corpses transformed into dragons may also have existed, but it was not very productive in surviving narratives.

The schedules of dragons and their relationship with light/darkness

As a parallel inquiry to the survey of topographical data presented above, the sources were combed for whether there was a specific time of day and year, or weather conditions, that were associated with dragons. The information proved more limited than regarding the physical settings. Regarding seasons, Bjarnar saga hítdœlakappa62 and Ragnars saga loðbrókar63 mention the dragon fights happening during the summer. In Gull-Þóris saga the first dragon encounter can be surmised to happen sometime in the fall or winter, as Þórir dreams of his encounter with Agnarr in the fall, where he obtains the information about Valr, and they seek the dragon “litlu síðar”64, that is, “shortly after”. Other two sagas are more specific: in Hrólfs saga kraka, the beast is said to have attacked for the last two winters in a row, specifically around Yule’s Eve (“Jóla-aptan”)65; while in Konráðs saga, the dragon and other beasts haunt the city during autumn-nights66. Speaking of times of day, there are slightly more encounters with dragons happening during the evening/night (seven)67, but some dragons are also specifically encountered at noon (two)68, and even more so at dawn or in the morning (five)69. Considering lighting conditions, one should add that dragon caves are pitch black in both Þiðreks saga and Flóres saga, while the one in Gull-Þóris saga is conversely said to be shining bright. Seldom, dragons bring with them unexpected weather conditions - in Dínus saga, the dragon brings darkness and shadow with it70, while in Valdimars saga the dragon manifests dark clouds, fog, and fiery thunder71. I do not think enough data is available to speak of true tendencies, but one can perhaps state that dragons seem to be slightly more associated with dark visibility and cold seasons. We need to bear in mind that these are not hard rules. Contradictory instances are present even within the same type of narrative (e.g. a dragon raiding a population center, which variously occurs in the morning or at night). Nevertheless, they seem to be creatures of habit, often said to do one of two things regularly at specific times: attack towns, or drink water (the latter probably owing to the story of Fáfnir) - these are the main contexts in which times of day are mentioned.

Some conclusions about draconic landscapes

As stated above, forests, rocky areas, and aquatic spaces are all frequent landscapes featured in dragon episodes. Nevertheless, one should bear in mind that they do not appear isolated, and several landscape motifs are often clustered together. To a point, landscape elements mirror the types of narratives being represented. What we can call "heirs of Fáfnir”, for example, i.e. men who transform into dragons while holding treasures, are often represented in a cave/lair, near water. However, Þiðreks saga, which contains an alternate version of the Sigurðr dragon-slaying relocates the fight from a heath into a forest72 - this can be well understood by the generic context of the same basic tale belonging here to a text which owes so much in style to knightly romance, being composed, at least in part, of translated material from medieval German literature73. Dragons which are fought by knights are indeed often found in the middle of a forest, sometimes already in battle with a lion, and often try to take both knight and lion to a rocky outcrop or cave where they feed them to their young.

However, these are not perfect indicators of what landscapes to expect: medieval authors were creative with the material and did not statically reproduce the landscapes they found in their inspirations when crafting new stories. Things get especially muddled when we get into the indigenous riddarasögur, which tend to mix motifs from several sources in their narratives. A good example of this is Ectors saga, where we find three knights fighting dragons, but all of them occurring in different landscapes: the episode of Ingifer, a shapeshifter, involves a cave, mountains, a track left by the dragon (much like Fáfnir), but proximity to a populace (whereas Fáfnir was completely isolated); the dragon-lion episode faced by Trancival takes place in a forest, by the sea; and the episode involving Ector himself and the shapeshifter-dragon Argus is very similar to the Ingifer-episode but involves a forest, a river with a bridge, and a nearby town severely affected by the dragon. We will look at the Ectors saga episodes further below, as we consider the effects of dragons on the environment.

The dragon and environments

Integration with the milieu

Dragons’ relationships with the environment are seldom harmonic, but those do exist. As they are fewer, we will start by reviewing the examples I found of draconic integration. For one, dragons are sometimes inserted into marvellous landscapes74 which seem to take on the properties of the treasures that dragons are connected to: we find a golden forest in Blómstrvalla saga, where even the rocks are made of gold75; and one also in Þorsteins þáttr forvitna76. Yngvars saga víðfǫrla shows us a hill that seems made of gold, because it is completely covered with serpents and treasure77. However, no other instance of a dragon being one with the landscape is as blatant as the landváttr of east Iceland in Heimskringla that was mentioned above. In that episode, not only does the dragon act as a guardian spirit of the land, but it also acts in the protection of the Icelanders. It would be interesting, perhaps, to consider this spirit in accordance with the idea of mythological dragons and serpents connected to the cosmology itself78. However, contrary to the dragon-spirit of East Iceland, the Eddic dragons are, at best, neutral, and, at worst, harmful to the mythological representations of a stable natural world. Jǫrmungandr/Miðgarðsormr encircled the ocean and all of Miðgarðr, embodying the idea of domesticated chaos and of temporarily stable unity of the world, but all that crumples away in Ragnarǫk, as it unleashes the power of the ocean into the land79. Níðhǫggr, the underground dragon who gnaws at corpses, is also mentioned in relation to Yggdrasill, living near its roots alongside other serpents and constantly eating away at them80. This Eddic notion may have been especially productive regarding the conceptualization of great worms, as we will see below that saga dragons often cause damage to trees and other natural environments by their mere presence.

Environmental Hazards

We will now move on to the most impactful cases where dragons make themselves felt. All of them have to do with a notion of non-shared space which seems to accompany dragons through the sources. They are not only greedy for wealth, but also for space: we see this from the most influential, and, by all evidence, earliest, of Norse dragon tales, with Fáfnir, the quintessential Germanic dragon, who isolates himself completely from society with his gold. This is a tendency in dragon episodes: they inhabit wild and fundamentally marginal spaces, opposite to society; when they interact with urban and populated spaces, either those moments are temporary predatory incursions, or more permanent stays lead to devastating consequences for the human inhabitants of the area.

The isolation of dragon landscapes is a feature searched for by shapeshifters who guard their treasures upon transformation, and seems to be a natural feature of those dragons which show no hint of having a human past. Dragons also guarantee that their space continues to be isolated: Fáfnir tells himself of one method he used to ensure others kept away from him: “svá fnýsta ek eitri alla vega frá mér í brott at engi þorði at koma í nánd mér”81 [so I blew poison in all directions away from me, so that no one dared to come into my proximity]. Whether in the wild or in an urban setting, dragons cause people and animals to move or keep away. I have mentioned before the serpent-city of Konráðs saga, about which the rumour goes, to paraphrase, that it was inhabited by people who were entirely driven out by serpents who harmed them82. The entire population of the city seems to have been substituted by serpents/dragons who now fill several social roles, posing as guards, entertainers (the juggling ormar), and one king, with his ægishjálmr83, the helm-of-terror that Fáfnir is also said to bear in his legend, which also drove others away in fear84. This is perhaps taking to the limit the circumstance that seems to be developing with the dragon of Þóra in Ragnars saga loðbrókar, taking up progressively more space and forcing people in the kingdom to reluctantly cohabit with it until Ragnarr steps in:

“Þar kemr, at eigi hefir hann rúm í eskinu, ok liggr nú í hring um eskit utan. Ok þar kemr of síðir, at eigi hefir hann rúm í skemmunni, ok gullit vex undir honum jafnt sem ormrinn sjálfr. Nú liggr hann utan um skemmuna, svá at saman tók höfuð ok sporðr85, ok illr gerist hann viðreignar, ok þorir engi maðr at koma til skemmunnar fyrir þessum ormi nema sá einn, er honum færir fæðslu, ok oxa þarf hann í mál. Jarli þykkir mikit mein á þessu”

[“Then the day came when it had no room inside the box, and it lay in a ring around the box. And it happened later that it had no room in the bower - and the gold grew underneath it just as much as the serpent itself. Now it lay outside, around the bower, so that it put its head and tail together, and it became hard to deal with. No one dared to come to the bower because of this serpent, except for the person who brought its food - and it required an ox for every meal. This seemed to the jarl to be a great harm”]86

In Ragnarssona þáttr, people are said to be afraid of the same dragon‘s savagery87. Similarly, in the first episode of Konráðs saga, it is said that nobody dares to go outside in the open during the autumn-long nights because of the dragon ("fyrir sakir þessa hins grimma dreka mátti engi maður haustlanga nótti úti vera undir berum himni“)88.

Not only does the dragon drive others away from the space it chooses to take, but it also alters the physical reality and the dynamics of said spaces in destructive ways. Before moving on to changes in the natural landscape, we will first continue looking at its effects when intruding on human space. In both Tristram sagas, the translated and the original romance, the dragon has a similar effect, killing people and cattle in the city, and in the case of the indigenous saga, causing people not to go outside when it became dark89. In Hrólfs saga, Bǫðvarr-Bjarki the regular attacks by the monster seem to “lay waste to the domains and cattle of the king.” (“eyða ríki ok fé konungsins”)90. Two of the dragons in Ectors saga have similar effects. Take the dragon Argus, who has installed itself over a bridge that led to an abundant forest where the people of the castle foraged their sustenance. These are the effects of the dragon‘s presence:

"Mꜳ nu eingi fara yfir modunna þuijat ormurinn blęs eitri suo aull iǫrd er suort ij nand og drepur będi menn og fe og er suo s(agt) ath bratt mune eydazt91 casta(linn).”92

[Now nobody could cross over the river because the serpent blew poison, such that all earth was black in its proximity and killed both men and cattle and it is said that soon the castle will waste away.]

The first dragon of the saga, Ingifer, also has pernicious effects on the nearby city:

“Hefir hann þar uerith xxx ꜳra […] hann eitrath ꜳ þꜳ er fellr wm borginna og uerda menn langa uegu vatn ath sękia. Drepur hann będi menn og fenad.”93

[He has been there for 30 years […] he has poisoned the river which comes from the city and men must now go a long way to seek water. He kills both men and cattle.]

Furthermore, the cityscape is described as seeming to bear marks of the dragon‘s prolonged presence: “allir borgar ueggr (voru) suartir og suo iǫrd ij nand borginne. enn griot uar orm skridith sem gullz litur uęri áá.”94 [“All the walls of the city and the earth around it were black, but the stones where the dragon slithered were golden”]. Blackened walls and earth, perhaps because of the dragon’s poisonous emanations, while it leaves a golden track wherever it slithers.

Going from Kathryn Hume’s typology for dragon fights95, we can consider these fights to have a very marked social impact. Not only the hero (or a maiden chained to a rock, to use Hume’s example) is at stake, but whole societies are being heavily damaged by the dragon. The vanquishing of the beast gains impact in the narrative since it is not only a passing depredation but a regular one that can even have terminal results for the communities. Speaking on the occasion about the dragon fight of Beowulf, Christine Rauer proposes that when presented within a social context, dragon fights may betray some hagiographical influence in their origin, even Scandinavian ones, giving precisely, among others, the examples of the Tristram sagas96. I believe there is some merit to this theory, and I feel it is reinforced when we observe the poisonousness of dragons in rivers. Aside from the above-cited example of Ingifer in Ectors saga, the third dragon, Argus, also poisons the river, even after death: “Enn er ormurin uar daudur drogu menn hertugans hann af steinnboganum og brendu hann aa bali. enn steyptu öskunne ij moduna.”97 [“and when the serpent was dead, the duke’s men dragged him [dragon] from the bridge and burned him on the bank, and cast the ashes into the river”]. Similarly, the dragon (Siggeus) of Yngvars saga is pestilential after being killed, its stench killing six men who looked closely at its corpse, and affecting many others, so that they have to steer away from it quickly98. It is also significant that in Valdimars saga, after the poison-spewing shapeshifting queen Lúpa is defeated, one of the actions taken to return to normalcy is to clear the plains of the city of poison (“uoro *hreinsadjr allir vellir af eitrj“)99. This motif of the pestilential dragon has antecedents in early hagiographical tradition100 and even classical antiquity101.

Not only through poison does the dragon mark the natural landscape. Due to the enormous forces at play, both the dragon’s and its enemies’, several sagas mention trees being damaged during dragon fights102 - it would be tempting to find here perhaps a faint echo of the function that Níðhǫggr and the serpents seem to perform by the ash Yggðrasill, but similarities end at the function (being harmful to trees), not extending to the form - Níðhǫggr and his serpent companions are gnawing at Yggdrasill, but in the sagas we never see dragons gnawing trees. We can also count the earthquakes and tremors provoked by the dragons’ movements and death struggles among the ways in which dragons affect the landscape, Fáfnir is a prime example103, and so is Argus: “uard nu suo mikil gnyr ath fiǫrbrotum ormsinns ath allr skogur og fiǫllinn skulfu sem ꜳ þręde leki.” 104 [“there were so great clashes from the death-struggles of the dragon that all the forest and the mountain shook as if they were swinging from a thread”]. Dragons shape the earth, as when one flies so close to the ground in Þiðreks saga that his claws act almost as a plough (“Hann flýgr náliga með jörðu sjálfri, ok hvervitna sem klær hans taka jörðina, þá var sem með inu hvassasta járni væri höggvit” [He flies close to the earth itself, and wherever his claws touch the earth, it was as if it were struck with the sharpest iron])105; or another leaves a huge track as vestige of its passage: “ein mikil slóð. Þessa hafði farit einn dreki”106 [“A great track. This had been trodden by a dragon”].

The earthquakes and destruction provoked by the dragon’s sheer movement and death-strugglesall seem to take us back to a mythological scale, where the whole environment can be altered by gigantic creatures of enormous power, although in the Eddas, differently from most sagas, we find dragons embedded in the structure of the cosmos itself. No worse movement can be imagined than that of Miðgarðsormr: first107 as a warning, when Þórr manages to slightly lift it off the ground (believing it to be a mere grey cat, as one of the three deceptive challenges imposed on the god by the giant Útgarða-Loki), the effect is that “hræddusk allir”108 [“all were terrified”] - such was the danger of the sea-serpent loosening its grip on the world; secondly, when the full effect of the former threat is unleashed, as Miðgarðsormr “snýsk […] í jǫtunmóð ok sœkir upp á landit”109 (“turns itself in a giant’s rage and advances into the land”), letting loose the waters of the ocean upon Miðgarðr as part of the destruction of Ragnarǫk, when the world as both god- and humankind knew it would cease to be. As part of that event, the Miðgarðsormr fights and is defeated by Þórr, simultaneously killing the god with its poison. Saga dragons are not usually integrated into the landscape in a similar, but the notion seems to have remained, even in Christian times, that a dragon on the move is rather impactful, and thus it wreaks havoc and shapes the environment in multiple ways as it goes about fighting heroes, as dragons are wont to do.

Concluding remarks

The environments of dragon episodes tend to adhere to certain predictable distributions along genre and narrative types, similarly to how the terminology of dragon works (ormr tending to characterize wingless Fáfnir-like serpents and dreki almost always applied to winged beasts defeated by knights) alongside certain types of stories; but neither one nor the other are hard-and-fast rules that we can take with us as guaranteed expectations into any text. As we know that treasures and shapeshifters are to be expected when ON dragons are at stake, I hope to have shed some light into the most important elements of dragonscapes as well: one can count on rocky terrain, water, and forests to be present in different combinations; and one can count on a dragon to be a nuisance to others, wherever it may be, even to the very place where it lies.