Introduction

Summarizing is a succinct, compact, and objective presentation of the most important points of a text and involves “faithfully presenting ideas or essential facts contained in a text, providing elements that do not require consultation of the original text” (Medeiros, 2006, p. 61). In addition, there are summaries with different functions. A text is summarized as a study on the same text (this is the case of the school summary) or as an initial framework of an article (this is the case of the abstract). The summarization process also involves the producer’s subjectivity and is based on the semantic operation of inference, which is linked to the notions of presupposition and misunderstanding (Fiorin, 2002). Specifically, to make a summary, the reader needs an understanding of the source text to infer the propositions present in a text and to highlight the implicit processes in the text to write them in the summary. The text producer, when writing a product of the summary genre, would not be extrapolating the basic subject present in the original text, but rather interpreting and consequently writing what is implicit (but implied) in the textual structure, thereby seeking a greater degree of coherence (Chen & Goodman, 1998; Van Dijk, 2004). Therefore, it is clear that the preparation of the summary requires semantic and extratextual knowledge for its writing.

The discussion about the summary genre is anchored in the theoretical and epistemological framework of socio-discursive interactionism (SDI) because it understands human behaviors as situated actions that have structural and functional properties as a product of socialization. This approach preserves the connection with human historicity and the social and psychosocial dimension of linguistic facts with a focus on the work of the production of written texts (Bronckart, 2008). In this sense, explicit knowledge of the language mixed with writing reinforces the ability to systematize rules, thereby leading the student to identify the error, favoring the development of reading and writing skills and language operations, which are built during the teaching-learning process. This perspective allows us to clearly understand how retextualization strategies contribute to the awareness of the student’s implicit and unconscious knowledge through a systematized work involving the organization of contents according to the stages of linguistic development. Retextualization, in this case, incorporates the idea that a text, when restructured, goes through several processes for effective reconstruction: reformulation through additions, substitutions, reorders, and cognitive reconstruction, which occurs in the field of comprehension through inferences, inversions, and even generalizations (Marcuschi, 2001). Therefore, the abstract or summarization of a text enhances the development of the explicit knowledge of the language and reading and writing skills. In this way, the activity of retextualization is one of the aspects of school learning and can be linked to numerous interdisciplinary activities. Because it is a communicative process, it is necessary to relate the Portuguese language to the production of summaries to the socio-discursive interactionist practice as a basis for practical research and functional results. Written language is complex and demands competence and performance from the writer during the construction process. Writing reflects the realization of the structures of ideas and the cognitive knowledge of the language as an act of communication and a product of social interaction.

Text Genres

For Bhatia (2001), text genres, such as the summary, can be seen from two different perspectives: first, as a reflection of the world and its communicative practices and, second, as an efficient pedagogical tool for the teaching-learning process. Therefore, reflections on the summary genre as a genre distinct from the others constitute an important theme for the school community. Dionísio et al. (2010) advocated mentioning this tool in the teaching-learning process and addressed the importance of researching this genre along with its specificities.

In this school context, the construction of the summary genre comprises a way through which the students translate their reading and demonstrate their knowledge about a certain area. By supporting the theoretical and epistemological framework of SDI, a social conception of all linguistic functioning is sustained because it is the purpose connected to the production of a certain text that conditions the linguistic strategies that will be mobilized. Therefore, summarization is considered an important tool for retextualization, considering the active and mediating process of work, wherein the student is the protagonist in the construction of knowledge, thereby learning the functioning of texts in favor of the development of metacognitive processes for the acquisition of autonomous and permanent learning. From this perspective, the work in the classroom with summaries as a strategy of retextualization is effective as a valuable tool for the construction of a work, wherein knowledge becomes significant, thereby promoting learning situations that reach the students in their development zone. The process, therefore, enables the improvement of textual production capacities supported by explicit knowledge as core competence and taught through a descriptive attitude of the process on the part of the teacher.

Therefore, a study is proposed to show that the summary genre enhances the development of explicit language knowledge and the development of reading and writing skills among students of the 11th-grade of a public school in north Portugal. Understanding the textual and discursive strategies of regularization and transformation (Marcuschi, 2001) is valuable for the retextualization and development of the student’s critical capacity at this stage of school development and is used in the production of the summary genre.

Accordingly, in this work, we pose the following questions: 1. Is the summary established as an autonomous genre in the school context? 2. Does the use of textual and discursive strategies in retextualization activities enhance the student’s development of reading comprehension?

Methodology

This study, conducted on October 19, 2019, aimed at understanding the difficulties 11th-grade students at a public school in the north of Portugal experienced constructing summaries within the school context. Consistent with this research, a didactic approach was used as proposed by Cicurel (1992) and Leurquin (2015) and articulated through the conceptions of reading as presented by Braggio (1992).

To answer the research questions, 17-morning shift students (14 young women and 3 young men) aged between 16 and 17 were recruited from the scientific-humanistic courses. These courses are embedded in the science and technology program and help young people in their construction of personal, social, and cultural identities. In higher education, the nature of an educational identity strengthens students’ specific training consistent in the domain of the respective course. Parents provided consent for their minor children and the school cluster ensured the research was conducted ethically.

Didactic procedure

The class was planned in three parts:

The first part included the oral language mobilization of previous knowledge acquired by students about the summary genre during their scholastic path. Questions asked were as follows: (i) When someone in your family misses the end of a movie and asks you to tell them what happened, do you describe it in detail or select the essential ideas? (ii) If you spend the weekend at a relative’s house, and on your return, your mother asks how the weekend was, do you report the main events or the secondary facts? (iii) When a colleague fails to attend a class and asks how the day before was, do you discuss the most important facts or secondary events?

This mobilization led to a class warm-up session about the working content. The primary objective was “to lead to a development of creativity as well as the production of a large number of ideas in the short period of time” (Masetto, 2003, p. 94). This session was performed orally or in writing and often used to mobilize ideas, concepts, and students’ previous knowledge about a subject. Therefore, it can be used “in order to collect suggestions, stimulating the generation of new ideas spontaneously and naturally” (Anastasiou & Alves, 2012, p. 89).

As instructors, we raise awareness among students by attempting to show them that they produced summaries in their social practices when they narrated various practices in their daily lives. The students’ repertoire was also mobilized to ensure that they could say what they expected from a text entitled, “Reading should be forbidden.” We understood that this stage would be important for reading and production because it allowed students to create hypotheses about the text in question, without having the material available.

In the second session, students were given the source text - a title by Guiomar de Grammont (1999; see Annex 1), and asked to follow the passage being read aloud. They were asked if they knew any names present in the text, such as Madame Bovary, Don Quixote, and Aristotle. They all claimed to know the characters. Afterward, students were asked to reread the passage quietly. By requesting this activity, we allowed students to “encounter” the author and better understand the reason for the chosen title. The selection of the text source was designed for the production of the abstract given the reflection it brings to reading-raw material for writing-as well as the informative and argumentative characteristics provided in the guidance documents curriculum based on the planning, implementation, and assessment of teaching and learning, thus leading to the development of skills listed in the profile of these Grade 11 students.

In the third session, we discussed the draft. Soon afterward, students were asked to retextualize the text in a written form in the definitive version and explain the textualization mechanisms present in the summary genre (Bronckart, 1999). This step was taken to mobilize the action and textual discursive capabilities.

For Marcuschi (2001), textual and discursive strategies are divided into a first set that follows rules of regularization and idealization, thereby merging into the strategies of elimination and insertion. These operations do not yet characterize a transformation itself in the base text. The second set comprises special operations, which follow the transformation rules and are based on substitution, selection, addition, reordering, and condensation strategies. According to Marcushi (2001), “These are exactly the ones that characterize the process of retextualization and involve more pronounced changes in the base text” (p. 76). In this sense, some textual and discursive strategies were selected for the activity of retextualization in the summary production making an essential activity for the formation of critical and autonomous readers.

Data Analysis

Using an analysis of the texts in Table 1, we used the parameters based on the principles of retextualization as cited in Marcuschi (2001) and Dell’Isola (2007). We hypothesized a theoretical path to achieve redefinitions and a new design for the study of the summary in the classroom by using textual and discursive strategies that involved the production of that genre. Therefore, we used the theory of textual genres in Marcuschi (2008), which addressed the notions of language, text, genre, comprehension, and meaning in the socio-interactionist view of language. The analyzed items were as follows: 1. Reading comprehension: This is the process through which cognitive strategies and necessary understanding skills were put into operation, thereby allowing the reader to extract and construct meanings from the text; and 2. Transformation and regularization: These are the practical processes of retextualization requested in textual production activities in the classroom. According to Marcuschi (2001), these textual and discursive strategies were transformations that automatically occurred by users of a language who were not aware of the complexities of operations. As an activity, these transformations were necessary for the elaboration of texts. The analyses about the irony, intertextuality, authorship and paraphrase were chosen and mobilized from their strong presence in the source text and were explained to the students for the production of the abstract as follows: i. Irony: This is a figure of speech that comprises the use of a word or expression in such a way that it has a different meaning than usual and produces subtle humor. The analysis of irony is present among the researched items because the source text has irony as a striking characteristic; ii. Intertextuality: This is a textuality element that ensures the text makes sense. According to Koch (2004), “a text is inserted in another previously produced text (intertext), which is a part of the social memory of a collective or discursive memory of the interlocutors” (p. 17). This element was selected because of the source text summoning other texts for the production of meanings; iii. Authorship: Possenti (2002) observed, “there are signs of authorship when several language resources are more or less personally managed” (p. 124). The author of the text revealed his voice, re-elaborating and architecting other voices; iv. Paraphrase: The paraphrase is discursively built because it “reveals a radical relationship between its interior and its exterior; and from that exterior [...], there are other texts that give rise to it, which predetermine it, with which it dialogs, resumes, alludes, or opposes” (Koch, 1997, p. 46). Regarding Figure 1, the analysis of the texts was made in the light of textualization strategies (Marcuschi, 2008), the retextualization of academic texts to abstracts (Dell’Isola, 2007; Matêncio, 2002), and the processes of production and organization of textual architecture (Bronckart, 2001, 2008). In addition, the term strategies refer to the comprehension and interpretation of texts from reading, in the same way, Solé (1998) and Kleiman (2012) used the term to refer to mechanisms/operations performed by a subject to execute an objective. It is considered as satisfactory reading comprehension based on the student’s active attitude, which builds the meaning of the text considering certain reading strategies, such as previous knowledge, reading objective, comprehension self-monitoring, and summarization (Kato, 1986; Leffa, 1996; Solé, 1998). Therefore, the student mobilizes the ability to paraphrase the source text, considering the essential and secondary ideas, using textual discursive strategies for the construction of the summary, and printing authorship marks based on the production context. Partial reading comprehension starts from the principle of the lack of attribution of meanings that guide the construction of the summary, thereby listing the essential ideas of the source text and reframing them through discursive textual strategies (Marcuschi, 2001). Unsatisfactory reading comprehension involves texts that use the source text as a copy for the construction of the summary, thereby neglecting the process of reframing from the reading activity (Solé, 1998).

Scholars such as Bakhtin (1992), Koch (2002), Dolz et al. (2004), and Marcuschi (2009, 2010), presented theories in which the idea of texts as social events was inserted, and the subjects were considered protagonists in their productions and textual analysis. According to Moran (2015), the active methodology is characterized by the interrelation between education, culture, society, politics, and school being developed through active and creative methods based on students’ activity to promote learning. This methodology is an important means for the teaching-learning process because these are guidelines that guide the educational processes and materialize strategies promoting significant contributions to the act of learning. Therefore, research is configured here based on descriptive-interpretative procedures of a qualitative and reflective nature on the teaching-learning process.

Results and Discussion

Individual analysis of some texts

When analyzing reading comprehension as a result of a complex activity in which the reader must perform different mental operations and use many types of knowledge, three levels of cognitive ability are presented. These provide a guideline for classifying the analysis of students’ texts as satisfactory, partial, and unsatisfactory comprehension. The three levels of cognitive abilities for reading comprehension are as follows: 1) Information Localization: The individual must be able to locate one or more parts of information in a text. Searching and selecting information are tasks that often appear in people’s daily lives because they are necessary when reading texts of different configurations. In this category, tasks range from retrieving specific and often explicit information in the text to combining multiple parts of imbricated information, some of which may be outside the body of the text. 2) Text Interpretation: It consists of the ability to build meaning and elaborate inferences. For the reader to develop an interpretation of the text, it is necessary that the reader reaches a deeper level of understanding and not just a superficial understanding of the written material. Thus, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms of explicit or implicit cohesion, to know how to elaborate high-level inferences, and to be able to organize and deal with contradictory or ambiguous information. 3) Reflection and Evaluation: The read content is defined as the relationships that the reader establishes between a text and their experience, knowledge, and ideas. This domain requires the reader to relate information that is in the text with knowledge from other sources.

In all analyses, a comparison was made between the student’s text and the source text. In Text 1, we describe the analysis of some students’ texts and their evaluation (i.e., partial, satisfactory, and unsatisfactory reading comprehension).

[Translation: Guiomar de Grammont, who is the author of the text entitled “Reading Should be Forbidden,” starts by saying that reading is bad for people because it awakens the society to a reality that is nonexistent and difficult or even impossible to reach and can create problems, such as frustration or madness. He gives the example of Don Quixote and Madame Bovary.

According to the author, we would die happy and ignorant (that is, without knowledge) without reading, and therefore, we would dedicate ourselves more to everyday life.

He also says that reading takes us on shortcuts that should not be explored, in addition to stimulating the imagination that does not match reality.

He advises schools, parents, and teachers to not give books to children. Reading can make us overly conscious, which can lead to the realization that we are not that free.

According to him, reading cannot be granted to everyone because it can become dangerous.]

The student activates the cognitive knowledge of partial reading comprehension in the summary. Observe the following fragment: “reading is bad for people because it awakens the society up to this nonexistent and difficult-to-achieve reality. According to the author, we would die happy and ignorant, that is, without knowledge.” In this way, the student mobilizes knowledge, raises hypotheses, and fills gaps by using strategies for adding and eliminating linguistic elements. It is noted, “Advise schools,” inserts the intertextuality of the characters of Madame Bovary and Don Quixote present in the text but does not dialog with the contribution they can make to the reading or the message proposed by the text. Thus, the student is distracted by the importance of verifying that intertextuality is a constituent and a constitutive element of the reading and writing process and refers to the various ways wherein the production and reception of a text depend on the knowledge of other texts for understanding. Therefore, intertextual knowledge is what allows the student to understand how a text is always related to other texts in a relationship that can be explicit or implicit, both in terms of its form and content. Furthermore, the student produces a summary with misconceptions regarding the understanding and copying of parts of the text. It is observed in the following text: “Which can lead us to realize that we are not so free”/“reading cannot be given to everyone because it can become dangerous.”

[Translation: This text discusses the importance of reading.

It is said, in an ironic way, that reading is harmful to human beings, inducing madness and causing them to have another view of the world that, of course, is true.

Children whose parents make them read become adults who are concerned with world problems; this is the power that reading holds over people. Without reading, humans are satisfied, not having to worry about anything, and are more satisfied with everyday reality.

Reading leads to pleasure and imagination, thereby making humans create other ways to reach their goals. Reading transports us to another reality, which had never been imagined before reading. Reading arouses more interest and curiosity about things.

It is also necessary to understand what we are reading to culturally enrich ourselves. Reading is a power granted to few. Additionally, reading promotes the expression of feelings and makes us better understand another person’s vision.]

There is a development of the reading comprehension present in the text under analysis and the perception that the source text reveals, ironically, the importance of reading. The retextualization is presented with the authorship of ideas for the reconstruction of the summary by using words that confirm the idea present in the source text, such as “reading does harm to the human being, thereby leading to madness and providing another view of the world that is supposed to be true...” The students reframe the information in the source text by highlighting their competence and progress toward a mature reader, who shows an understanding of the read text.

There is the authorship of ideas for the retextualization of the source text because the student seeks to print his marks in the text. The return to the literal ideas of the source text is little marked. However, there is a lack of textuality elements, such as cohesion in textual reconstructions. The student’s ability to summarize is satisfactory with the presence of important reformulations for the understanding of the text. Moreover, there is a break in semantic parallelism in some parts of the text, for example, in “Children whose parents stimulate them to read become adults worried about the problems of the world; this is the power that reading has over people...” It is noted in this insert that the student used independent juxtaposed prayers placed in the text, thereby disregarding connectors that link them.

Therefore, the student is shown as an active word processor, verifying hypotheses that lead to the construction of their understanding, controlling this understanding, and engaging in a process of prediction and continuous inference. This process is supported by the information in the source text and the student’s reframing ability. The student understands the summary as a reconstructive element, dependent but not subservient to the source text, and understands that, as a producer, it is up to them to choose the direction to be given to that genre.

[Translation: Reading should be prohibited. Reading allows humans to glimpse achievable realities.

Those who read can become dangerous people because they see other solutions and ways of facing the world’s problems. Without reading, people would be happier and more dedicated to work, family, etc.

With reading, however, it is possible to gain knowledge. It is possible to cultivate imagination and stimulate dreams.

It is not advisable for parents and teachers to arouse the taste of reading in children because they may become interested in it. Reading promotes people’s awareness of their rights, which would be impossible to control in a society.

Reading for utilitarian reasons is on the rise to better understand society. Reading is a power that is for everyone, thereby promoting communication and making us capable of understanding the world.]

This summary corroborates the researcher’s inference when diagnosing the difficulties of high school students in working with the genre in question, for example, “Reading should be forbidden”/“Reading allows men to glimpse realities that are never possible to achieve.” The student reproduces the “ipsislitteris” resumption of what is found in the text, thereby confirming the insufficiency about the performance of cognitive competence regarding reading comprehension because this could reframe the read text. For Solé (1998), reading comprises a reframing process wherein the reader activates knowledge to understand the text, thereby making inferences of what was understood about it.

In the fragment made by the student “Those who read can become a dangerous person because they will see other solutions and other ways of facing the world problems.” We noticed that the student does not perceive the irony present in the construction of the source text, thereby working with “copy” and “paste” of what exists in the text. For Marcuschi (2001), the retextualization process involves complex cognitive and textual discursive strategies. Regarding the transition from a language modality-written to writing-the importance of activating satisfactory cognitive and textual discursive knowledge for an adequate construction of the text is observed. In this sense, it is clear that there is an interaction between the student reading and producing the source text. By aligning this with the summary, we noticed that it promotes the work with strategies that facilitate students’ development and communicative competence, thereby mobilizing learning toward the citizen’s training of the apprentice and following the objectives of UNESCO/2030. The institution aims at education for students wherein learning results are relevant and effective, thereby promoting lifelong learning for all because these approaches are important for the development of sustainable societies.

The construction of textual and discursive strategies of regularization and formulation are is also insufficient because the student continues their text by copying and pasting passages of the source text. See, for example, “With reading, it is possible to gain knowledge. It is possible to cultivate imagination and stimulate the dream.”

It appears that it is expensive to understand the process of written-written retextualization for the student. Marcuschi (2001) confirmed “the act of producing meaning from a text is an act of understanding it, not of understanding it well. Good understanding of a text is a particular and special activity” (p. 46). The accentuated tasks in writing and reading are often in the background, and the student needs “time” to develop this very important skill in the teaching-learning process.

Redesigning the work with the summary genre in the classroom, understanding the process of retextualization encompassed the genre, and reframing its concept will significantly contribute to the improvement of the state of the art concerning linguistic studies.

The theoretical incongruences presented in the traditional view of the summary and the research carried out through this sample underline the need to revisit the concepts of the summary because a work of “cutting” is perceived, thereby reinforcing the difficulty of the producer in the process of reading and writing. It is believed that, once the concept of the summary has been redesigned, we would sharpen the student’s interpretative autonomy to parallel it with the linguistic clues present on its surface, thereby differentiating them in the act of saying.

After analyzing the texts of all students, it was observed (see Table 1) that only 35% of the students presented a satisfactory understanding of the text, and 82% copied fragments of the source text literally. Textual and discursive strategies of addition, substitution, and elimination occurred in 82% of the cases, along with the reformulation of the text in 76% of the cases. Consistent markings of authorship appeared in only 23% of texts, and only 1% recognized the irony present in the text (see Table 1). It is noteworthy that the summaries produced by the students were exchanged among themselves for reading, analysis, and as evidence of the studied and rewritten strategies.

Table 1: Characteristics of the 17 texts

| STUDENTS’ CHARACTERISTICS | Number of texts | % |

| Satisfactory reading comprehension | 6 | 35.3 |

| Textual reformulation and regularization present in the text | 13 | 76.5 |

| Discursive textual strategies of addition, substitution, and elimination | 14 | 82.4 |

| Non-recognition of the Irony present in the text | 17 | 99.0 |

| Recognition of Intertextuality | 3 | 17.6 |

| Copies of literal fragments of the source text | 14 | 82.4 |

| Consistent marks of authorship | 4 | 23.5 |

| Consistent paraphrase | 7 | 41.2 |

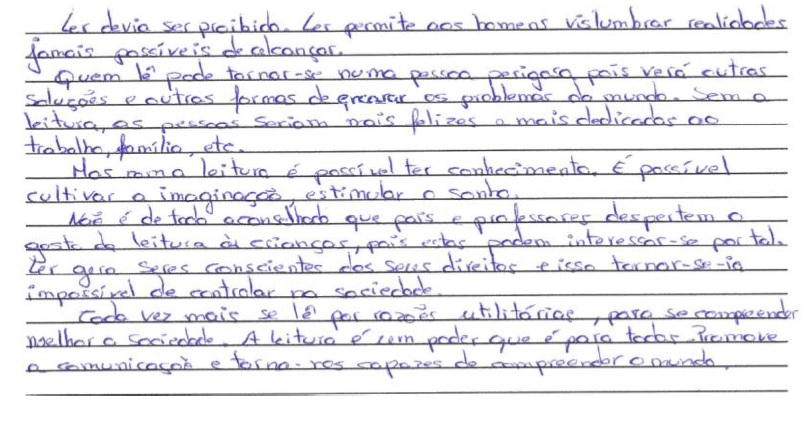

Figure 1 represents the level of appropriation of the summary genre among the satisfactory, unsatisfactory, and partial categories for the 17 analyzed texts. It can be observed that 62% had an unsatisfactory level of appropriation and only 32% had a satisfactory level.

As seen in the theoretical framework, the analysis of the summaries produced in this work showed that genre knowledge required more than knowledge of the structure from a macro point of view. It was necessary to understand how to build this genre also from a micro perspective and be able to put knowledge into effect in the textualization process. Therefore, a didactic intervention describing the textual and discursive strategies involved in the retextualization process promoted the student’s insertion in discursive practices in a session of the appropriation of academic-scientific concepts and procedures, that is, effective know-how to do and know-how to say. Considering the limitations of the research, the students could have had a more successful appropriation if the didactic approach had considered other factors.

Theories of the analysis of textual genres in teaching and learning situations and understanding of the conception (Adam, 1992, 2011; Broncart, 1999, 2008) showed the students’ difficulties regarding textual comprehension and the copy of a fragment of the source text. Therefore, it was consistent with the production of texts (Dolz et al., 2004) and with the need to rethink how they are equipped today in the classroom, and to review paths for meaningful learning.

Discussions were held on linguistic and communicative aspects that involved the realization of the abstract genre. They clarified the importance of textual strategies that were composed in a way to promote that they should act as creators of knowledge and not reproducers of information.

Thus, activities should be conducted that allow students to access new language practices and knowledge of genres that they have not yet mastered. Didactic actions for the teaching-learning process of textual production were considered conditions from a communication situation with the initial production. Accordingly, they predict the production of the abstract, prioritizing linguistic and discursive dimensions, and provide a final product, which integrates learning and allows the student to review and rewrite their text.

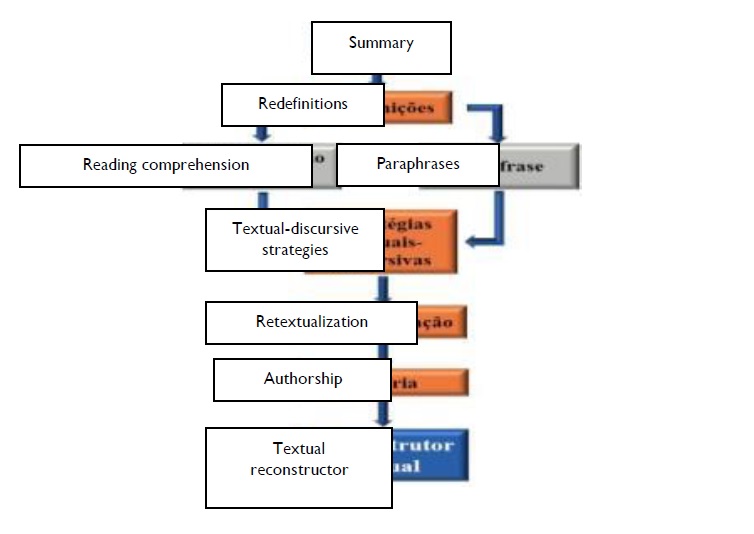

From this analysis, some inconsistencies were revealed regarding the traditional concept of the summary genre and its effective construction, thereby confirming the need to understand it as a reconstructive and autonomous element. Therefore, it is considered that the summary is capable of improving the communicative competence of the student. The contribution of the active methodology as the reference base was verified here for teaching textual production because it increases cognitive flexibility, which is the ability to change and perform different tasks and mental operations, thereby adapting to unexpected situations for the verification of knowledge about the language. Therefore, it is a necessary didactic procedure that excels in the process of retextualization to understand that teaching and learning become attractive when based on processes of questioning, creation, reflection, and interaction (Figure 2).

It becomes clear that the work with language, intertwined with the individual practice of construction and production of meaning through the summary, constitutes valuable support for the development of reading comprehension. It is noted here that the manner of producing and understanding texts lacks the systemic approach concerning the production of the genre. By analyzing what the summarization process means in the current context, we perceived that students see it only as understanding. However, it is also necessary to understand summarization during reading, and summary in the process of reducing secondary and essential information by taking advantage of only the basic meanings for understanding the text.

Therefore, given the summary genre analysis, we emphasize awareness about an approach in which explicit knowledge is solidified and supported by rigorous descriptions and conducted by evidence-driven empirical texts.

Conclusion

There are problems in the definition and consequent elaboration of the summary, quite possibly, because of performances in the reading and writing process reinforced by some theoretical inconsistencies regarding this genre. Many authors admit that the summary is only a work of “cutting,” despite the interpretative autonomy of the reader, which-although the linguistic clues present in the text-differs in the act of saying when the producer builds the text.

The said genre is considered autonomous (Machado, 2010), thereby pointing out the characteristics and the need to review its concept in the face of textual and discursive strategies that involve the process of retextualization. According to the Curricular Guidance Documents, this statement is justified because it is necessary to stimulate essential learning in articulation with the student’s profile (Portugal, 2018). Therefore, it is considered necessary to work on student competence in writing by placing them in situations that make them write summaries, present on topics, and show critical appreciations, thereby defending active learning as a way to arouse interest and develop students’ learning. This allows them to build their knowledge because, in the modern world of constant transformation, education has the challenge to be more flexible by building multiple and continuous learning processes.

Based on the analyses conducted and the results obtained, a new perspective of the summary genre is adapted (see Figure 2). The use of textual and discursive strategies through the contextualization of contents, and interdisciplinary as a practice for the teaching-learning process is based on critical and reflexive action. An interactionist paradigm is suggested wherein the teacher and student articulate their actions with the world and with knowledge. In this way, researchers strive for a change in thinking and practices in favor of sustainable educational development, working with an active methodology in which the student is an active character in an autonomous and participative way. Accordingly, the teaching of the summary will promote skills that will collaborate with learning to think and learning to understand in search of sustainable thinking, thereby promoting a vision of the future for the nation’s development.