Introduction

Word stress has a relevant impact on the intelligibility of second language (L2) learners’ pronunciation (e.g., Checklin, 2012), not only because words minimally differ in terms of stress but especially because this property facilitates word identification and sentence segmentation into words (e.g., Field, 2005; Tremblay, 2014). Some studies even present data showing misunderstandings, communication breakdowns, caused by unexpected or unclear stress location, and argue that word stress is not a top priority in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) pronunciation teaching, but it certainly is important and needs to be taught (e.g., Lewis & Deterding, 2018).

There is already some empirical evidence of difficulties in word stress acquisition (e.g., Couper, 2012; Field, 2005; Lewis & Deterding, 2018), even in learners who have been learning an L2 for many years, such as Chinese learners studying EFL for 7-11 years (e.g., Bu & Zhou, 2020; Liu, 2017). Despite this, the L2 acquisition of suprasegmentals, namely word stress, is still understudied, at least compared to the attention given to the acquisition of segmental properties (e.g., Bu & Zhou, 2020; Liu, 2017). For instance, to the best of our knowledge, the number of empirical studies on the word stress acquisition in the European variety of Portuguese as a Foreign Language (PFL) is very limited, and even the attention given to graphic accent in textbooks and grammars seems to be scarce (e.g., Silva, 2020). Chergova (2020) observes stress errors in many 1st-year and 4th-year Bulgarian students who learn PFL at the university. Castelo and colleagues (2018) report that many teachers responding to a questionnaire identified word stress production as difficult or very difficult in the first semester of PFL learning by Chinese students and a bit difficult in the second semester. However, in the analysis of stress production by 7 Chinese learners with different proficiency levels, Castelo and Santos (2017) found only very few stress errors (1%) and some accent errors (29%).

Considering this situation, the present work is a pilot study having two goals: (i) to gain a better understanding of the performance in word stress production and perception by a group of learners of PFL; (ii) to draw the relevant pedagogical implications for adjusted pronunciation teaching practices. Also, as claimed by Munro and Derwing (2015), classroom studies are important in pronunciation teaching. So, this study aims at reaching the two before-mentioned goals as a classroom study.

After this “Introduction”, five main sections will include the following contents: description of the morphophonology of word stress in Portuguese; explanation of the method used in this pilot study; presentation of the results obtained in terms of scores as well as types of errors; discussion of the data and its pedagogical implications; final remarks.

Word stress in Portuguese

The word or lexical stress in Portuguese can fall on the antepenultimate, penultimate or final syllable of a word (see e.g. Mateus & Andrade, 2000; Vigário, 2003). However, the frequency of each type of stress pattern varies greatly: the proparoxytone words correspond to around 2% of the tokens in Portuguese, the paroxytones to 54%, the oxytones to 16% and there is around 28% of monosyllabic words, which are very frequent and can count as oxytones (Vigário, Frota & Martins, 2010).

The stress location is determined by morphological and lexical information according to many proposals (see e.g. Mateus & Andrade, 2000; Vigário, 2003). In this free stress language, it is possible to have what we can call “stress minimal pairs”: words or forms of words contrasting in stress position (see examples (1) and (2)).

(1) Minimal pairs: distinction of words

avo / avô ‘small part / grandfather’

tato / tatu ‘tact / armadillo’

pais / país ‘parents / country’

música / musica ‘music / (s)he writes (the) music’

(2) Minimal pairs: distinction of word forms

falaras / falarás ‘(you) speak-pluperfect / (you) speak-future’

falaram / falarão‘(they) speak-perfect / (they) speak-future’

Table 1 summarizes the word stress location in Portuguese.

Table 1: Word stress location in Portuguese

| Cases | Word stress location | Examples | |

| Noun subsystem | unmarked pattern | last stem vowel/diphthong | •class-marker -a, -e, -o: cadeiras, ave, tato, avo ‘chairs, bird, tact, small part’ •maracujá, azul, colar, tatu, café, avôs, rubi, fariseu, irmão, armazém ‘passion fruit, blue, necklace, armadillo, coffee, grandfathers, ruby, pharisee, brother, store’ |

| marked pattern | penultimate stem vowel/diphthong | •class-marker -a, -e, -o: médica, árvore, farmacêuticos ‘woman doctor, tree, pharmacists’ •cônsul, âmbar, viagem, órfão, táxis ‘consul, amber, trip, orphan, taxis’ | |

| Verb subsystem | present tenses | penultimate word vowel/diphthong | falo, falas, falamos, falam ‘to speak’ |

| past tenses | theme vowel | falaste, falaras, falaram, falássemos | |

| future tenses | 1st vowel of tense-mood-aspect morpheme | falarei, falarás, falarão, falaríamos | |

(see e.g. Mateus & Andrade, 2000; Vigário, 2003)

As shown in the table, there are two subsystems (noun and verb), and the noun subsystem includes two patterns (unmarked and marked). In words following the unmarked pattern of noun subsystem, the stress falls on the last vowel or diphthong of the derivational stem. This means that the stress is located on the penultimate syllable of words with an overt class-marker (-a, -e, -o, spelled as A, E or O without graphic accent at the word end, before the morpheme for plural) - see cadeiras, ave - and on the last syllable of words with no overt class-marker - see maracujá, café. In the words with marked pattern, the word stress is located on the penultimate vowel or diphthong of the derivational stem. For example, the last vowel of the derivational stem in médica is i but the stress is placed on the previous vowel, é, because the word is lexically marked as an exception to the default pattern; so, the stress falls on the penultimate vowel of the derivational stem, which corresponds to the antepenultimate vowel of the word. The word âmbar is another example of marked pattern for word stress: the stress should be on the last syllable (a is the last vowel of the derivational stem as the word presents no overt class-marker) but it is lexically marked as an exception to the default pattern and consequently the stress falls on the penultimate vowel of the derivational stem (which also corresponds to the penultimate syllable of the word).

The verb subsystem comprises three rules: in the present tenses, the stress falls on the penultimate vowel or diphthong of the word; in the past tenses, it falls always on the theme vowel (-a- for verbs ending in -ar, -e- for verbs in -er, -ir- for verbs in -ir); the forms in future tenses have the stress on the first vowel of the tense-mood-aspect morpheme.

The morphophonology of the word stress is mirrored in the spelling system. In fact, the Portuguese orthography is supposed to show the readers which is the word stressed syllable, as well as other pieces of information on the vowel quality (e.g., if it is oral or nasal, open or closed). Although there exist several rules and exceptions concerning how the stress and vowel quality are indicated through orthographic diacritics, for the purpose of this study, it is enough to highlight two general principles:

the tilde diacritic (~) marks word-final nasal vowel or diphthong and this almost always bears the word stress;

the real graphic accents (grave accent, ^, for medium vowels and acute accent, ´ , for non-medium vowels) almost always indicate a stress marked pattern.

Table 2 shows how this works, by illustrating when there is a need for a graphic accent.

Table 2: Need for graphic accent in Portuguese

| Cases | Word stress location | Examples | (No) need of graphic accent |

| Ending in A, E, O, AM, EM | After penultimate vowel/diphthong | maracujá, café, avôs, armazém | Marked pattern → accent |

| Before penultimate vowel/diphthong | médica, árvore, farmacêuticos | ||

| On penultimate vowel/diphthong | cadeiras, ave, avo, viagem, falam | Unmarked pattern → no accent | |

| Other endings | On last vowel/diphthong | azul, colar, rubi, irmão | |

| Before last vowel/diphthong | cônsul, âmbar, táxis, órfão | Marked pattern → accent |

(see e.g. Castelo & Sousa, 2017)

The words ending in A, E, O, AM, EM (with or without final S, a non-relevant letter for this case) are by default stressed on the penultimate vowel/diphthong. If they follow the unmarked pattern, they do not need a graphic accent (e.g., cadeiras, ave). If, on the contrary, they bear the word stress before or after the penultimate vowel/diphthong, they must present a graphic accent that indicates this exceptional pattern (e.g., médica, avôs).

The words with other endings are normally stressed on the final vowel or diphthong. If that is the case, there is no need for graphic accent (e.g., colar, rubi); if they are exceptions, a graphic accent should be used to indicate that the stress falls on the vowel before the last vowel or diphthong (e.g., âmbar, táxi).

In summary, the Portuguese word stress can fall on one of the last three syllables of the word and its location is determined by morphological and lexical information (with different rules for the noun and the verb subsystems). The orthography is supposed to cue the word stress location and uses the graphic accent whenever a word follows a marked pattern for stress. As a result of these rules, (i) the proparoxytone words are always marked and cued by graphic accent and (ii) in the noun subsystem the unmarked pattern includes both paroxytone words with an overt class-marker and oxytone words with no overt class-marker.

Method

The pilot-experiment presented in this paper is a classroom study and collects some preliminary empirical data on the performance of elementary learners of European Portuguese as a foreign language in the context of Language Lab II, one of the compulsory courses taught in the second semester of a 4-year BA Degree in Portuguese. This academic degree is imparted in a college of the Chinese Special Administrative Region of Macau to absolute beginners who wish to be professionally active in the domain of Portuguese as teachers, translators, among others. As the data were collected during the first months of course, the participants had been learning Portuguese for around 6 months. The class had 22 students but only 12 gave their informed consent to use their results in the research and completed all tasks and therefore are included as participants. These 12 students constitute a semi-homogeneous group: all are Chinese, but they have two native dialects (4 native speakers of Mandarin and 8 native speakers of Cantonese).

The goal of Language Lab II is twofold: (i) to develop some explicit knowledge on the phonetic-phonological properties of Portuguese and (ii) to consolidate the competences developed in all courses of the plan of studies (e.g., Reading, Grammar) in the oral modality. For that reason, it includes listening and speaking activities related to the speech acts, vocabulary and grammar presented in the other courses (e.g., food and ordering in a restaurant, hobbies and presenting one’s hobbies), as well as activities that focus attention on the phonetic-phonological topics (e.g., learning explicit rules about word stress, discriminating differences in word stress, producing controlled and spontaneous oral sequences that are challenging in terms of word stress).

This pilot-study presented three phases (see Table 3): the pre-tests phase, the Test 1 (3 weeks after semester’s beginning), and the Test 2 (5 weeks after Test 1). The amount of time between Test 1 and Test 2 was determined by course and school calendar constraints. During that interval (that also included a 1,5 weeks of holidays) the students continued the same type of work done in the pre-tests phase.

Table 3: Phases of the pilot-study

| Pre-tests | Test 1 | Test 2 |

|---|---|---|

| “Spelling-to-stress rules” Exercises | Discrimination based on lexical stress (words and sentences) Reading with preparation | Discrimination based on lexical stress (words and sentences) Reading without preparation |

Pre-tests

In the pre-tests phase, the students were taught the “spelling-to-stress rules”, a simplified version of the main rules to identify the word stress based on the words’ spelling (see Table 4).

Table 4: “Spelling-to-stress rules” (see Castelo, 2018)

| “Spelling-to-stress rules” | → Stress position | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| With accent (´, ^, ~) | → syllable with accent | São Tomé e Príncipe, Japão, Finlândia, Barém ‘Sao Tome and Principe, Japan, Finland, Bahrain’ |

| Without accent, ending in A, E, O, AM, EM (+S) | → penultimate syllable | Coreia, Cabo Verde, chamam, chamem ‘Korea, Cape Verde, to speak’ |

| ( Without accent, other endings (+S) | → final syllable | Portugal, Timor, Benim, Palau, Haiti, Peru ‘Portugal, Timor, Benin, Palau, Haiti, Peru’ |

The first rule states that in words with accent the stress is located precisely on the syllable with the accent. If the word presents no accent, then the students must check the word ending: in words ending in A, E, O, AM, EM (with or without final S, that is not relevant for this matter), the stress falls on the penultimate syllable; the words with other endings present stress on the final syllable.

After learning these three rules, students did several exercises related to word stress to ensure they can identify the word stress in explicit language knowledge activities and correctly use it in speaking and listening activities. The exercises consisted of underlining the stressed syllable of written words, identifying the rule that accounts for stress location in specific lexical items, reading words aloud and discriminating “stress minimal pairs”.

Tests 1 and 2

The two tests were completed almost at beginning of class, immediately after the homework correction, and took a total time of around 20 minutes. They included tasks of perception and production, and used similar stimuli and conditions, the only difference laying on the absence of time for preparation of the production task in Test 2.

The perception tasks were word discrimination (identifying the listened word in 10 stress minimal pairs) and sentence discrimination (identifying the listened sentence in 5 pairs of sentences which differed in one of the word stresses and sometimes also in a small number of specific sounds). The students listened to the audio files in the Language Lab system (using individual headphones, at their individual pace and as many times as they wished) and marked on an answer sheet the chosen option for each item.

The production task consisted of reading a small text presented on the answer sheet used for the perception tasks. To have empirical data about how good is production of word stress with under optimal conditions, in Test 1, students had around 5 minutes to prepare the text reading. After that, they read the text and their reading was recorded in the language lab system, which was Infinity DLL at the time. As the performance in the prepared reading was very good, a second test was done in which no time was given for reading preparation. This second reading was also audio recorded in the language lab system, which had changed to Sanako by this time.

The stimuli (words, sentences, and texts) used in both tests can be found in the appendix. In Table 5, some examples of the items used in Test 1 are presented.

Table 5: Some examples of the items in Test 1

| Tasks | Examples of items |

|---|---|

| Word discrimination (10 items) → mark on a paper | ( último ‘last’ ( ultimo ‘(I) finish’ |

| Sentence discrimination (5 items) → mark on a paper | ( Há muitos peros na loja. ‘There are many apples in the shop.’ ( Há muitos perus na loja. ‘There are many turkeys in the shop.’ |

| Reading (1 text) → audio record | O Antúrio é uma das plantas tropicais mais comercializadas no mundo. […] ‘Anthurium is one of the most commercialized tropical plants in the world.’ […] |

The audio stimuli for word and sentence discrimination were produced by a male native speaker of European Portuguese (aged 46 and an experienced teacher of Portuguese as mother tongue and as a foreign language) and recorded with a digital recorder in a partially soundproofed room.

The texts used in the reading task of both Test 1 and Test 2 are short (a total of 65 words) and present simple grammar structures but deal with a topic which is unknown to the students and demands specific vocabulary (more precisely the properties of specific flowers: anthurium and petunia). The choice of unfamiliar topic and vocabulary aims at showing how well the learners can assign the word stress to new words. To make the texts comparable, we control the stress pattern of the 39 or 40 words which are nor clitics and nor forms of “to be” (a very common verb and consequently too familiar for the students): 5 of them are proparoxytones; 11 exhibit are oxytones with a stress pattern different from the most frequent one; and the 23-24 words left present the most frequent stress pattern in Portuguese (i.e., paroxytone words ending in A, E, O, AM, EM). The amount of three different stress patterns partially reflects the frequencies of tokens in Portuguese: more cases of paroxytones, less of oxytones and a small number of proparoxytones.

The answers given by the participants in the perception tasks were coded as correct or incorrect. The records of the production task were listened and coded by the author (a researcher with training in phonetic transcription and an experienced teacher of PFL): each word that is not a clitic or a verbal form of “to be” was marked as correct (1 point), partially correct (0,5 points, when there were “mixed situations” like a correct word stress and also short breaks among the word’s syllables) or incorrect (0 points) in terms of word stress assignment. The points obtained in the three tasks were converted into percentage scale, so that they are more easily compared.

Results

The presentation of the results will include the observation of the scores obtained by the group of participants in the different tasks, as well as the frequency of errors registered in the production (reading) task according to several linguistic variables.

Scores in the tasks

As mentioned before, the scores obtained by the participants in the three tasks were converted into percentage scale. Table 6 presents the mean scores in Test 1 and Test 2, as well as the difference between them. To compare the results in the two tests (two-related-samples), the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used because the sample size is very small (N=12). The reported p-value is always two-tailed.

Table 6: Comparison of scores in Tests 1 and 2

| Test 1 (mean) | Test 2 (mean) | Test 2 - Test 1 Difference | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall discrimination | 76% | 81% | 5% | .261 |

| Word discrimination | 73% | 87% | 14% | .010 |

| Sentence discrimination | 82% | 70% | -12% | .167 |

| Reading | 86% | 73% | -13% | .002 |

The word discrimination task in Test 1 presents a mean of 73% and it increases to 87% in Test 2, being this difference statistically significant (p=.010). The score in the sentence discrimination task is higher in Test 1 (82%) and lower in Test 2 (70%), but this difference does not reach statistical significance (p=.167). If the scores of word and sentence discrimination are merged, the overall discrimination score in Test 1 (i.e., Discrimination 1) presents the mean of 76%, while Discrimination 2 has a slightly higher mean of 81%, but again the difference between Discrimination 1 and Discrimination 2 is not statistically significant (p=.261).

The mean score obtained in Reading 1 (i.e., reading task in Test 1) is 86% and in Reading 2 it is only 73%. The difference between the scores obtained in these two tests, -13% in Test 2, is statistically significant (p=.002).

Table 7 shows the non-parametric Spearman correlation coefficients between the scores of Reading and (overall) Discrimination in Tests 1 and 2.

Table 7: Correlations between scores of Reading and Discrimination in Tests 1 and 2

| N=12 | Discrimination 1 | Reading 2 | Discrimination 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading 1 | Corr. Coeff. | .666* | .856** | .660* |

| p-value | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.019 | |

| Discrimi-nation 1 | Corr. Coeff. | .487 | .413 | |

| p-value | 0.109 | 0.182 | ||

| Reading 2 | Corr. Coeff. | .583* | ||

| p-value | 0.047 | |||

The only correlations that do not reach statistical significance are the ones between Discrimination 1 and Reading 2 and between Discrimination 1 and Discrimination 2.

Frequency of errors in the reading task

A list with all words used in the reading task and their frequency of errors is presented in Table 8.

Table 8: Words used in the Reading task and their frequency of stress errors

| Words in Test 1 | No. of errors | Words in Test 2 | No. of errors |

|---|---|---|---|

| tupi | 11 | ||

| hibridação, florescem | 10 | ||

| tropicais, popular, florais | 7 | têm, subtropicais, herbáceas | 9 |

| buquês | 6 | petúnias | 8 |

| orgânica | 5 | tropicais, protegidos, espécies | 6 |

| comercializadas, existem | 4 | jardineiras, índios | 5 |

| cultivo | 3 | significa, semeadas, primavera, origem, maciços, América | 3 |

| originária, adaptação, flor, matéria | 2 | qualquer, lugares, grupo, ambientes | 2 |

| planta, variedades, boa, utilizada, deve, local, direto, geral, planta, fácil, rica | 1 | verão, principalmente, pleno, obtido, cultivadas | 1 |

| antúrio, plantas, mais, mundo, Colômbia, geralmente, muitas, tem, durabilidade, como, corte, arranjos, deixada, pouco, sol, modo, terra | 0 | vermelha, vasos, sul, sol, podem, nome, mês, grandes, flor, desde, ano, algumas | 0 |

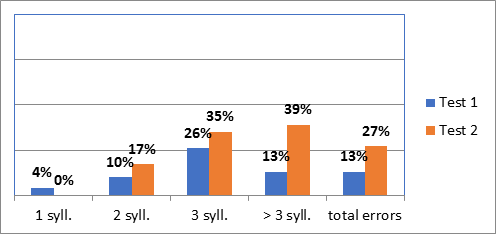

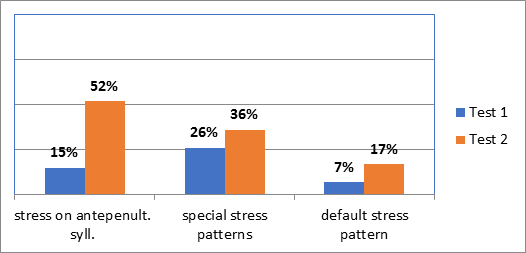

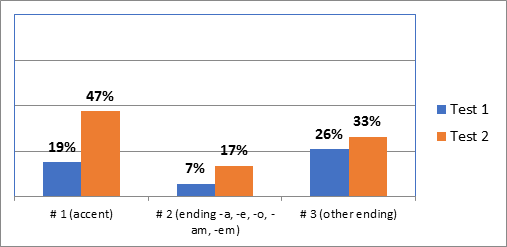

The following charts present the frequency of stress errors (in percentage) in the reading task according to different linguistic variables: word size (Chart 1), stress pattern (Chart 2) and “spelling-to-stress rule” (Chart 3). All of them consider the results obtained in Test 1 (where there was a preparation time of 5 minutes) and in Test 2 (with no preparation).

When considering all stress errors (“total errors”), 13% is the mean rate of errors in Test 1 and 27% in Test 2. This increase in the percentage of errors in Test 2 occurs in words of all sizes, from 1-syllable words to items with more than 3 syllables. The word sizes with a higher mean of errors are the longer ones: 3-syllable words (26% in Test 1, 35% in Test 2) and words with more than 3 syllables (13% in Test 1, 39% in Test 2).

As mentioned in the Method section, we adopted a stress pattern distinction while building the text used as written stimulus between default stress pattern (paroxytones ending in A, E, O, AM, EM), proparoxytones and all other stress patterns, named as “special” because they differ from the default one. When considering this variable, the lower mean of errors is associated with the default stress pattern (7% in Test 1, 17% in Test 2). As for the most frequent errors, they occur in words with special stress patterns in Test 1 (26%) and in proparoxytones in Test 2 (52%). The second most frequent errors are associated with proparoxytones in Test 1 (15%) and with special stress patterns in Test 2 (36%). As before, the patterns for the most frequent errors are reversed in Test 1 and in Test 2.

If we take the “spelling-to-stress rule” taught to the students as a variable, we observe only 7% to 17% of errors (Test 1 and Test 2, respectively) in words following rule 2 (which coincide with the default stress pattern mentioned in Chart 3). The most frequent errors are reversed in Tests 1 and 2: in prepared reading, there are more errors in words following rule 3 (no accent and endings other than A, E, O, AM, EM - 26%) than in words of rule 1 (with an accent - 19%); in unprepared reading, more errors occur in words of rule 1 (47%) than in words of rule 3 (33%).

Discussion and pedagogical implications

As previously mentioned, the first goal of this pilot study is to gain a better understanding of the performance in word stress perception and production by a group of learners of PFL.

The results show that the level of stress perception is good (76%-81%), at least when there is the opportunity to repeat the listening as many times as wished, and the items are short (in this case, 15 contrasting words and 5 contrasting sentences). However, in further research on this topic, it would be important to assess the stress perception with no repetitions, in a more naturalistic approach, and to include more longer items. At the end of his study, Field (2005) also claims the need to evaluate the learners’ perception performance with no time to think about what was heard and in sequences larger than the citation form, to fully understand the word stress perception in further research.

The performance in word discrimination shows a statistically significant improvement in Test 2, as expected due to the increase in time of learning and task experience. Nevertheless, the results in sentence discrimination are worse in the second completion of the task and no specific reason for that can be found. It is possible that it might be caused by idiosyncrasies of the items, and therefore in studies continuing this line of research more items should be included for sentence discrimination.

In terms of word stress production (while reading a short text), the level of performance is very good with preparation (86%) and only good without preparation (73%). This decrease in the scores of Test 2 reaches statistical significance. Although both reading tasks constitute instances of controlled speech, the unprepared reading is closer to the uncontrolled speech and this performance difference (between prepared and more controlled reading vs. unprepared and less controlled reading) contributes to highlight the importance of assessing oral skills through both controlled and uncontrolled speech, as advocated by many authors (e.g., Ellis, 2005). Also, it is possible that in free communicative production even more stress errors would occur, since the Chinese language is tone-oriented and might lead to a certain ‘stress-deafness’ (e.g., Bu & Zhou, 2020).

The correlation coefficients between perception and production in Tests 1 and 2 (i.e., Discrimination 1 and 2, Reading 1 and 2) are also informative. Firstly, the statistically significance of the correlations between stress perception and production in each test (Discrimination 1 and Reading 1; Discrimination 2 and Reading 2) is consistent with the frequent claims for correlation between segmental perception and production found in the literature (e.g., Best & Tyler, 2007; Escudero, 2005; Flege, 1995). Besides that, it is important to note that the scores in Discrimination 1 do not significantly correlate with any other scores except those of Production 1 (the counterpart task at the same time). This corroborates the hypothesis that there is some problem with the results on the specific task of Discrimination 1.

The frequency of stress errors in the reading task according to linguistic variables helps to understand where the learners’ difficulties lie. In Test 1, there is an impact of word size on the performance level: in fact, there are less errors for 2-syllables words, followed by words over 3 syllables and 3-syllables items. Here it should be noted that in Portuguese, in terms of tokens, the 2-syllables words (c. 43%) are much more frequent than the 3-syllable words (c. 20%) and the items longer than 3 syllables (c. 9% - see Vigário, Frota & Martins, 2010), and this might cause a bigger acquaintance with the stress patterns in disyllabic word size.

The stress pattern also influences the accuracy in word production: the success rate is higher in words with the default stress pattern, followed by words stressed on antepenultimate syllable and, finally, items with special stress patterns. If the results are observed from the perspective of “spelling-to-stress rule”, the same tendency is evident: the success rate is higher for rule number 2 (endings in A, E, O, AM, EM), followed by rule number 1 (accent) and rule number 3 (other endings). This convergence in the results of variables ‘stress pattern’ and ‘spelling-to-stress rule’ is not surprising, however, when we note that the words associated with rule number 1 include all proparoxytones of the text and three other oxytones.

Although the tendencies are like the ones observed in Test 1 (the easiest condition), in Test 2 some small differences occur regarding the most frequent errors. One difference in Test 2 is that fewer errors occur in 3-syllable words compared to longer words. This may have two causes: (i) several longer words have an accent that helps to identify the stress location whenever the learners have time to pay more attention to it (and they did not have that time to do it in Test 2); (ii) there are 15 longer words in Test 2 compared to 11 words in Test 1.

A second difference in Test 2 is the occurrence of fewer errors in words of special stress patterns (compared to the proparoxytones) and in words following rule number 3 (compared to words following rule number 1, which includes mainly proparoxytones and four other words). It seems that in Test 2 the participants had no time to reflect and apply the spelling-to-stress rules, and therefore the more marked cases (proparoxytones and words with graphic accent) present the worst results. On the contrary, when there is time for preparation, the application of the rules (namely the rule number 1, which indicates that the syllables with graphic accent are stressed) can occur and improve the performance. Besides, it is important to note here the parallelism of success rate with stress pattern frequency (e.g., Vigário, Frota & Martins, 2010): the paroxytone words are more frequent and present a higher success rate; then, the oxytones are less frequent and have a lower level of performance; finally, the proparoxytones are the least frequent and show the worst results.

The patterns found in the participants’ performance allow us to draw four relevant pedagogical implications for adjusted pronunciation teaching practices (goal 2 of this pilot experiment). Firstly, the relationship found between perception and production highlights the importance of also training perception while teaching pronunciation of stress, as advocated also by several researchers for pronunciation in general (e.g., Alves, 2015; Castelo, 2022; Celce-Murcia et al., 2010; Grant, 2014; Thomson, 2011) and for stress in particular (e.g., Liu, 2017).

Secondly, it is important to practice and assess both controlled and uncontrolled speech. In fact, these results corroborate the idea of moving from the promotion of explicit knowledge and concern for accuracy in controlled production to the use of that knowledge and concern for both accuracy and fluency in more communicative oral outputs (e.g., Alves, 2015; Celce-Murcia et al., 2010). So, the teacher should try to use ‘stress minimal pairs’ not only in exercises but also in dialogues and to elicit specific words in communicative speech.

The third pedagogical implication of these results is the relevance of teaching explicit knowledge. It seems that the students obtain better results when they have time to apply generalizations like ‘spelling-to-stress rules’, obtaining a better performance even in the most marked stress pattern as are the proparoxytones in Portuguese. In fact, many researchers claim for the importance of explicitly teaching the rules and/or stress patterns (e.g., Bu & Zhou, 2020; Checklin, 2012; Field, 2005; Liu, 2017).

Finally, the results indicate the existence of some ‘difficult areas’, some patterns (the marked ones) that are more difficult and should be practiced more intensively: the longer words (3 or more syllables) and the items with special stress patterns that correspond often to words following the third ‘spelling-to-stress rule’.

Final remarks

This pilot experiment reports empirical data on stress perception and production in PFL by a small group of Chinese-speaking learners. Although limited in number of tasks and participants, this study presents the advantage of reporting preliminary data for addressing an understudied topic in PFL. It also points out to different challenges to approach in further research: to collect data of a larger number of participants; to consider learners with different linguistic backgrounds (namely in terms of stress systems in their native languages); to include also other tasks, that are more naturalistic, communicative, and spontaneous; among others.

The study also supports some important pedagogical implications, that might guide not only the PFL pronunciation instruction, but also training studies where the weight of each implication is assessed.