1. Introduction

Brussels housing in the 1950s was characterised by overwhelming support for public collective housing policies. Two laws addressed the housing shortage following World War II: de Taye (1948 and 1953) and Brunfaut (1949). While the latter supported public housing, the first promoted home ownership. Eventually, de Taye would have the greater impact in Brussels, as housing development was essentially a matter of private initiative (Broes, Dehaene, 2016). In this context, the de Taye laws (1948 and 1953) not only allowed acquisition subsidies for the middle classes, but also led to massive reorganisation operations in working-class neighbourhoods or in Brussels’ 20th century outskirts, through the sale of large properties for the construction of high-rise modernist buildings (Leloutre, 2020). Among the actors who left their mark on the urbanisation of Brussels’ second belt, two private developers stand out: Jean-Florian Collin (Etrimo) and François Amelinckx (Entreprises Amelinckx). “Although Etrimo and Amelinckx were brothers-in-arms in the Belgian real estate business, Collin may be characterised as the real pioneer” with the creation of his first company as early as 1935 (Broes, Dehaene, 2016). With 14,000 dwellings built in Brussels alone, Etrimo left its mark on housing in terms of quantity but also on the Brussels subconscious, with its “exceptionally homogeneous” products (Ledent, 2014).

From its creation in 1935 through to the 1950s, Etrimo (Société d'études et de réalisations immobilières) built apartment buildings for Brussels’ wealthy. From the 1960s onwards, it specialised in providing the middle classes access to property, with the construction of larger housing estates on the outskirts of several large Belgian cities, Brussels in particular. In order to implement these estates, the company sought to purchase large land plots. In Brussels, such plots were still available in the city’s second belt. These were large landholdings (Château de Rivieren in Ganshoren, Château Lambeau in Woluwé-St-Pierre, etc.) but also former industrial sites or fallow land (sand quarries in Woluwé-St-Lambert, flooded marsh areas along the Biestebroeck wharf in Anderlecht, the Pécheries Royales watercress beds and vegetable gardens on the Watermaalbeek in Watermael-Boisfort, etc.). In the absence of legislation on height or density, Etrimo set the tone by negotiating directly with municipalities (Ledent, 2014). Interestingly, a new category of people were targeted by this urbanisation of Brussels’ second belt. Indeed, these private developments were intended for the middle class, among whom many were families returning from Congo, a former Belgian colony.

In this paper, we address the capacity of this category of people to generate inhabitant communities, as well as the potential of Etrimo’s collective estates to support these communities. Through what tangible and intangible means can a community be imagined, formed, and sustained, and how does that help us conceive and design communities in the future?

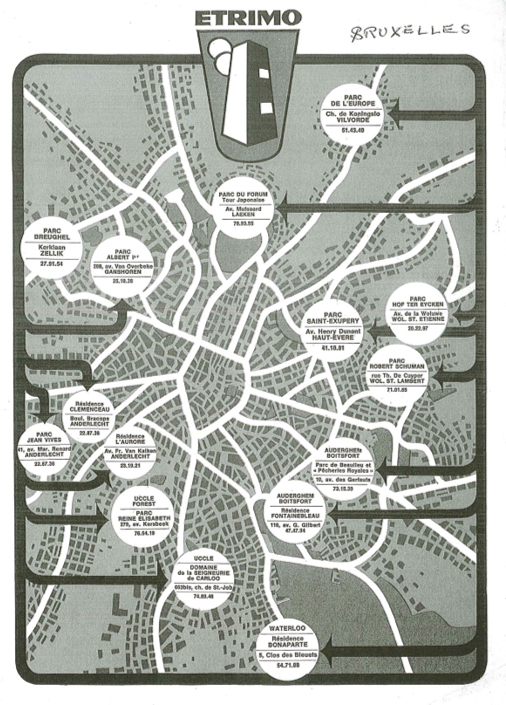

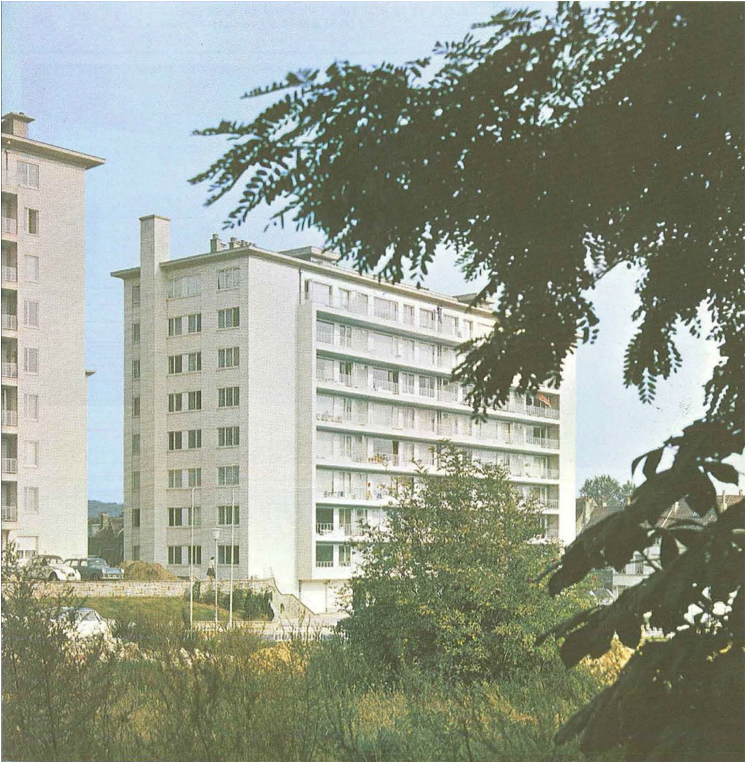

This question was applied to three case studies, Etrimo buildings dating to between 1964 and 1968 in Brussels (figure 1): Parc Albert in Ganshoren, Parc de la Héronnière et Beaulieu in Auderghem, and Parc Schuman in Woluwé-Saint-Lambert. These large housing estates share several features: a location in the city’s second belt, proximity to schools and shops, repetitive spatial organisation on the theme of isolated “buildings in a park”, and a majority of owner-occupants. They were chosen because of the availability of iconographic material (Ledent, 2014) and the possibility for interacting with original inhabitants.

Audrey Courbebaisse, 2021.

Source: Figure 1: The three case studies in Ganshoren, Auderghem, and Woluwé-Saint-Lambert

The research methodology consists of qualitative research undertaken at the crossroads where architecture meets the social sciences. From an architectural point of view, the Etrimo estates were studied by means of a spatial analysis of two types of elements: archive material (e.g., commercial brochures1, Collin’s writings2) and drawings of the existing situation (redrawn mass and floor plans, sections, etc.).

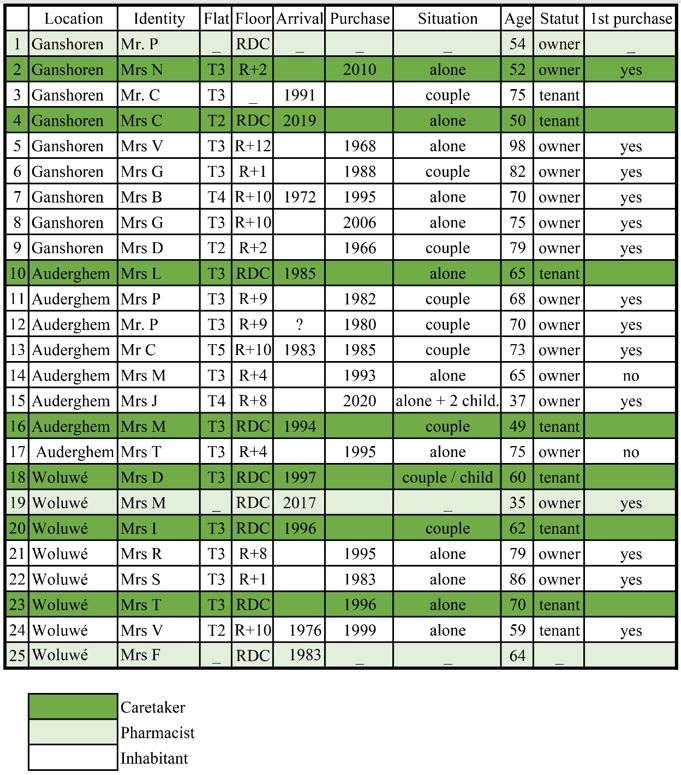

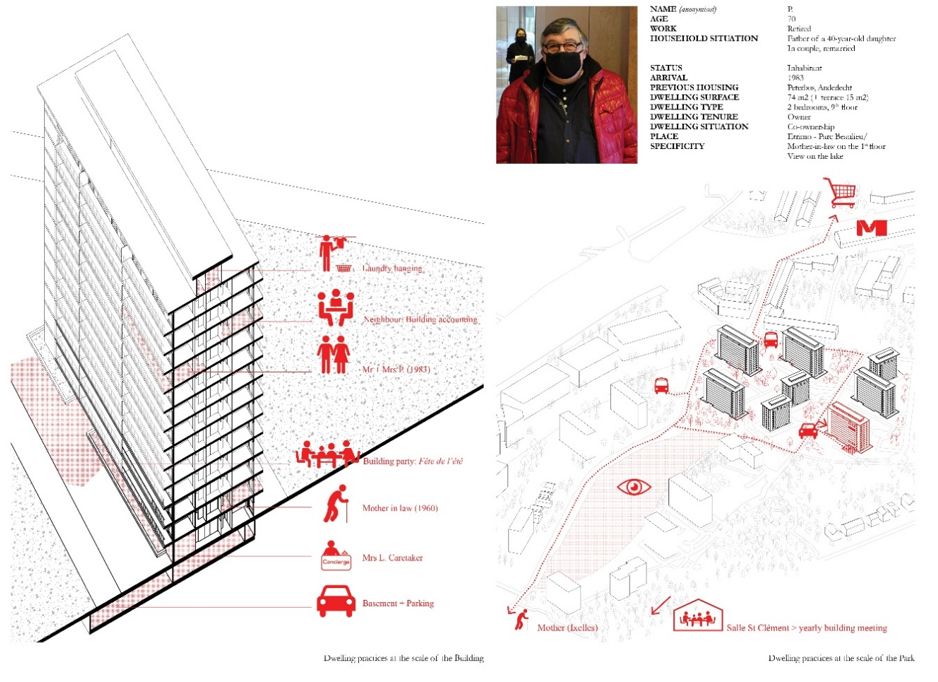

From a social point of view, the projects were visited in depth several times, which allowed us to make in-field observations as well as conduct 25 interviews with inhabitants (figure 2), caretakers, and several pharmacists working in the three studied buildings. The questions were structured according to several hypotheses of potential levers (spatial and social) that could enhance the creation of a community: residential trajectory, social dynamics, spatial dispositions, maintenance and management of the building and development, landscape amenities, and, finally, the large community formed by all the buildings built by Etrimo. The respondents were between 37 and 98 years old. Fifteen of the 25 were owner-occupants, seven were caretakers occupying the ground-floor lodge, and three were pharmacists working on the ground floor of the building. Although the population is gradually changing and many of the previous residents had already left or died, we were able to meet two households who bought off-plan in the 1960s. Most of the people we met had arrived between 1982 and 1999, illustrating a pivotal period of household renewal. Only five households that arrived from the 2000s onwards were interviewed, including only four persons who are still working. This can be explained in part by the timing of our visits (weekdays during working hours).

In order to highlight the spaces that can support an inhabitant community, we mapped the spatial practices of each interviewee on an axonometric drawing of each site (figure 3a and b).

Gérald Ledent, 2021.

Source: Figure 3A and 3B: Drawn survey of spatial practices (a) at the scale of the building - (b) at the scale of the park

This paper presents our research results in two stages. Each stage sets Etrimo’s intentions (what was designed) against present conditions (what happened). To study the initial intentions, we based our research on the primary sources at our disposal: sales brochures, Etrimo advertising posters, writings by Jean-François Collin on the legal and financial set-up of his business, plans of the housing units and estates. The analysis of present conditions relied on interviews with the inhabitants and in situ observations of living practices in the housing estates’ collective spaces.

The first stage investigates the individual level. How did Etrimo intend to urbanise the nuclear family, at the heart of the company’s projects? What today has become of this family and the environment that was intended for it? Second, we examine in what ways Etrimo positioned this family in a collective framework, whether through tangible or intangible devices, and how current representations and practices have engendered not one but many social and spatial communities.

2. Living in an Apartment

2.1. The Notion of the Nuclear Family

“In any case, whether it is the responsibility of the individual or the community, it must be borne in mind that it is the individual who pays; for it must be said and repeated that the community is only the sum of the individuals.” (Collin, 1968)

According to Jean-Florian Collin in L’Europe des Nations (1968), Etrimo’s imagined community was built as a sum of individualities. The basic individual was “a new man, an intelligent average man”. The question of repetition is interesting because identifying the repeated element allows us to establish a series and thus the imagined community of people.

A. The Nuclear Family

One of these features is the nuclear family, which was organised around “a new kind of man”, a man produced by the industrial world. Collin believed that the nuclear family was at the centre of society. “In 1967, a man produces so much that he is able to own a car (his first concern), household comforts, a house, social security, and then a pension”. Etrimo was thus interested in workers’ gentrification, as opposed to the bourgeois proletarianisation advocated by Karl Marx. This vision underpins Collin’s liberal views. He was a prominent member of the PLP, Belgium’s liberal party, in the 1960s. His was a typical post-war understanding of the family: a man going off to work and a woman working in the home. Middle-class family housing was organised around this scheme. Accordingly, Etrimo’s typical flat was designed for a couple with one, two, or three children. Parents were between 30 and 40 years old.

B. The Domestic Role of Women

Within this family, women were the guardians of domesticity. In Etrimo’s view, apartments were designed in every detail to lighten housewives’ burdens. In a letter specially addressed to them, Collin writes: “Madame: housing issues are essentially feminine (…) Many shops have been established at the base of the buildings”. We can imagine this was addressed to a housewife who did not drive. “The flats in Parc Beaulieu will delight you, as they are rational, modern and elegant. Designed to the last detail to make life easier for the housewife” (Etrimo, 1965).

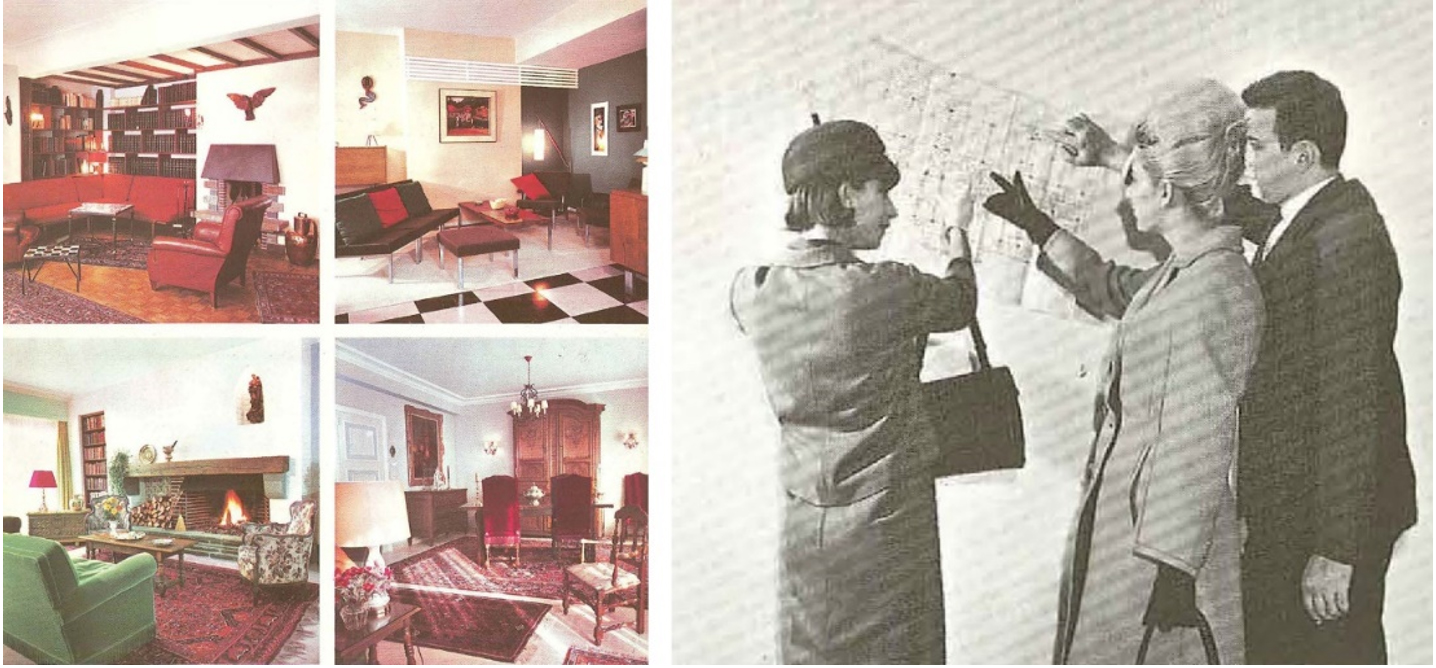

Collin appealed to the creative instincts of the housewife: “a very large living room, extended by a generous terrace, will allow your good taste and creative imagination to express themselves freely”. At the time, interior decoration and lifestyle magazines were gaining popularity. The French magazines Marie Claire in 1937, Elle in 1945, or special issues such as the 1951 issue of the magazine Science et vie, were specifically dedicated to the home. It should be noted that Etrimo flats were sold off-plan, with the possibility to adjust each dwelling (figure 4). For instance, in Ganshoren, a private staircase was installed to link the pharmacy to the pharmacists’ flat on the first floor. The finishes also varied according to the clients’ wishes and finances. Floor coverings, wall coverings, kitchen equipment, and terrace awnings were sold as options.

Etrimo (1963, pp. 91, 41).

Source: Figure 4: Collin appealed to the housewife’s creative instinct by making the apartments adjustable

C. Homeownership as a Means to Emancipate Families

Collin strongly believed that homeownership could emancipate these families. Another important idea for Etrimo was therefore the value of work and savings. Work should enable leisure time. Additionally, to complete his economic transformation, the new man must become a “wealthy man”. That is why the question of savings was so central to Etrimo’s strategy. Collin set up a savings system allowing access to property for as many people as possible, according to their salaries. In Collin’s mind, property was the basis for happiness.

A new civilisation, the “civilisation of urbanism”, corresponded to the new man. This was to bring two things to men: “To move in a harmonious environment and to be owner of his own home”. This evolution was both an economic transformation and a social promotion.

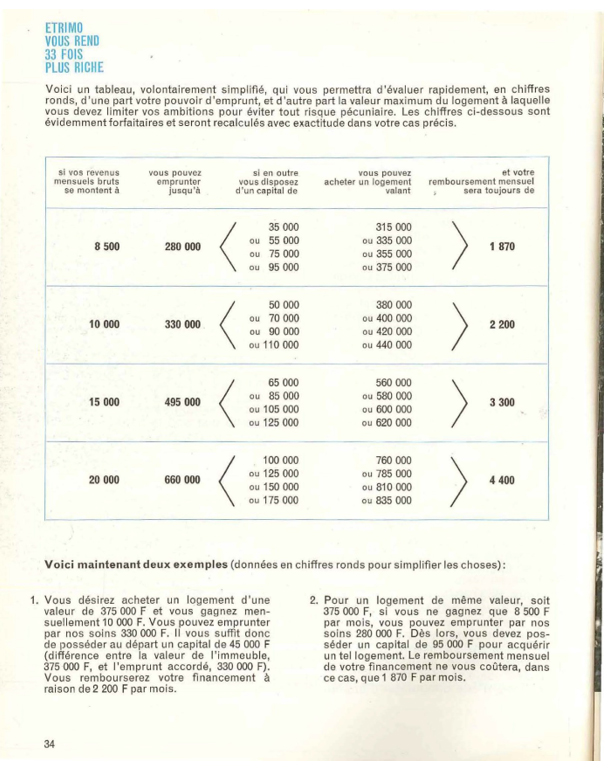

Etrimo’s housing corresponded to households earning between 6,000 and 20,000 francs3 per month. Etrimo imagined four economic classes, one “modest”, another “middle”, one “luxurious”, and finally one “grandly luxurious”. One of the company’s brochures states that, in 1966, “of the first 146 buyers of our social buildings: 20% earn between 6,000 and 10,000 francs per month, 16% earn between 10,000 and 12,000 francs per month, 33% earn between 12,000 and 15,000 francs per month and finally, 31% earn more than 15,000 per month” (figure 5). This salary range was extensive enough to include labourers, employees, and management. The average cost of a flat was about 400,000 francs4, which represented two years’ earnings. The repayment of the balance was equivalent to a monthly rent, with the difference that at the end of the term, the householder owned his dwelling.

2.2. Ageing and new family trajectories

Time has passed and Etrimo’s initial residents have aged or passed away. Some have gradually built networks of familial solidarity within the estates. New residents move in for motives that differ largely from those of the initial residents.

A. An ageing modern family

Among the older generation of inhabitants, we met families who arrived in the 1960s and others who arrived later, in the 1980s and 1990s. Both belong to the same “generation of a modern family” and form a separate group on the estate. What brings them together is their ages rather than their arrival dates. They usually share a common vision of life and are of a similar generation, as opposed to the younger, more recently arrived households. Some of them even socialise outside the building. There is a great deal of solidarity and mutual aid among this community.

“My neighbour is Greek and she's a friend. We've been on trips together, to Paris, to London, and when there’s something going on, we do everything together too. But for the rest, sometimes we don't see each other for three weeks, because that’s what we said from the start, not all the time together, because it doesn't last. Three weeks sometimes (...) And then she comes to ring or I go to ring, Are you still alive?” Woluwé, Mrs R, 79 years old, arrived 1995

“I said to myself, I know everything by heart, all the people of my age or a little younger or older, so I stay (...) I have a lady here above, I saw her again today. She is 90 years old, she is still fine. She doesn't walk any more, she’s at home all day, so every evening or twice a week, I go to her house to have a little chat, a drink to pass the afternoon.” Ganshoren, Mrs S, 80 years old, arrived 1990

B. Time-forged bonds

Over time, new relationships developed on the estates, including family networks that did not exist when the projects were first developed. Currently, residents from the same family form recurrent networks of acquaintances. We observed residential strategies where parents join their children or vice versa. For instance, we observed children who bought an apartment for their ageing parents. Some already live in the building while others plan to occupy the flat themselves one day. All the people we met spoke of a measured mutual aid, intimacy, and watchfulness from a distance. Their choices also reveal a strong attachment to the municipality in which some of them grew up and aged.

“Our daughter used to live in pavilion 2 and that’s how (...) She came to live here, she bought here, she bought a flat here, in pavilion 2. And we also started looking left and right and finally we found this. Well, we saw each other when we went to the market or something but we didn't depend on each other. But we got on well!” Ganshoren, Mr and Mrs G, aged 82 and 86, arrived 1988

“I look after the animals of my son who lives next door, here at the other entrance. When he goes to work, they come to me, so I’m never alone. He lives in Mum’s flat. I was the owner and when Mum died, he moved to the flat. Because she lived in a small house and I was in charge of it, going for a run every day...And I thought she was very isolated because she couldn’t move around anymore either, so I said to Mum, Listen, sell your little house and take a flat here so that I'm near you all the time. We had everything well organised, we would come and do her washing and I would go and prepare her dinner, in the evening I would go and make her sandwiches and give her medicine (...) And now it's my son who takes care of me, we do the shopping together.” Auderghem, Mrs T, aged 75, arrived 1995

“My son at that time was working in the police and he bought a house in the same street but on the other side and one day he said, 'Listen, it's better that you come to Woluwé too because I have to come here every time when you're in Forest, so I'm more at ease if you live nearby. I found this flat with the agreement we both made, he lives there and I live here. When we need each other, we’re here, but not always. Young people need to have their own life and old people are such a pain in the ass. We’ve always been there. We call each other, and when he has little cakes, he calls me, I come down, he gives me a little cake and when he goes on holiday, I’m there to look after the animals. And when I’m ill he also comes to help me.” Woluwé, Mrs R, 79 years old, arrived 1995

C. The evolution of the means of emancipation

Vectors of emancipation have evolved. In particular, access to property has become more difficult in Brussels, where the percentage of homeowners is much lower than in other parts of Belgium - less than 40% in Brussels for an average of 70% in Belgium (Statista, 2020). In addition, the share of housing costs in household expenditures has increased tremendously from Etrimo’s times to today, rising from 10 to 20% in the 1960s according to Collin (Figure 5) to 34% today (Statbel, 2018).

Nevertheless, we note that Etrimo’s apartments remain an interesting option for households as their average price remains below market. We might therefore conclude that, for many young households, Etrimo represents a stage of their life trajectory rather than a place to stay in the long term.

3. Housing families in a collective venue

3.1. Living together in a park

A. A repetitive model

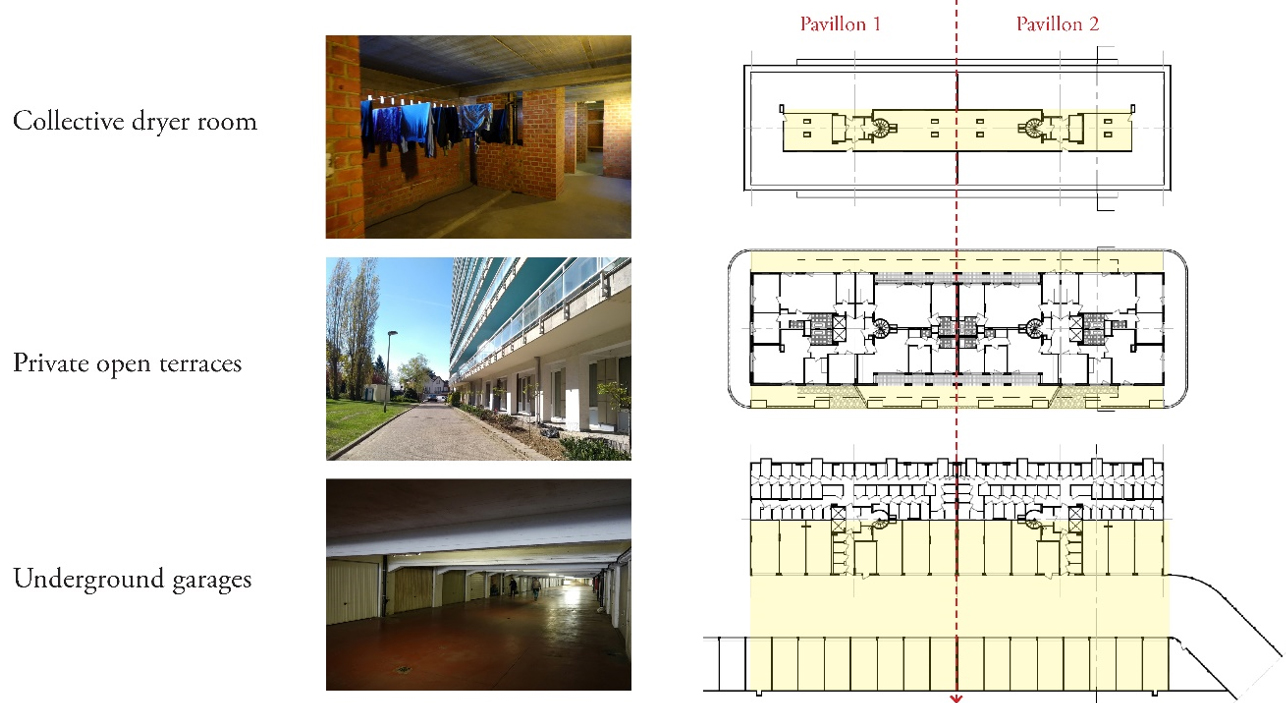

Etrimo’s collective housing projects were conceived and built in identical ways, based on the repetition of a standard building (i.e., the superposition of two T3 flats on either side of a stairwell) in a park. The horizontal juxtaposition of two, three, or even four of these standard buildings constitutes a “pavilion”. Within the pavilion, each dwelling benefits from a series of collective extensions, shared by two or even three buildings: collective drying rooms in the attic, porticoed galleries on the ground floor, and underground car parks. Finally, the pavilions all share the collective park and its facilities, which vary from one site to another (children’s playgrounds, sports fields, squares, etc.).

Another element contributing to Etrimo’s uniform image of is the common materiality of all buildings. Indeed, the buildings’ materiality and finishes contribute to creating a comprehensive and familiar image for Etrimo estates. The co-ownership regulations state that this characteristic aesthetic line has to be maintained: blue balcony ceilings, orange awnings, glass railings, interior decoration (a single artist decorated the halls, lifts, and landings of all Etrimo buildings) (figure 6). These elements make it possible to identify Etrimo buildings. These aesthetic codes contribute to the definition of an Etrimo community at the scale of the city.

Etrimo (1963, p. 57).

Source: Figure 6: A precise aesthetic that conveys the familiar image of Etrimo buildings

B. Buildings in a park

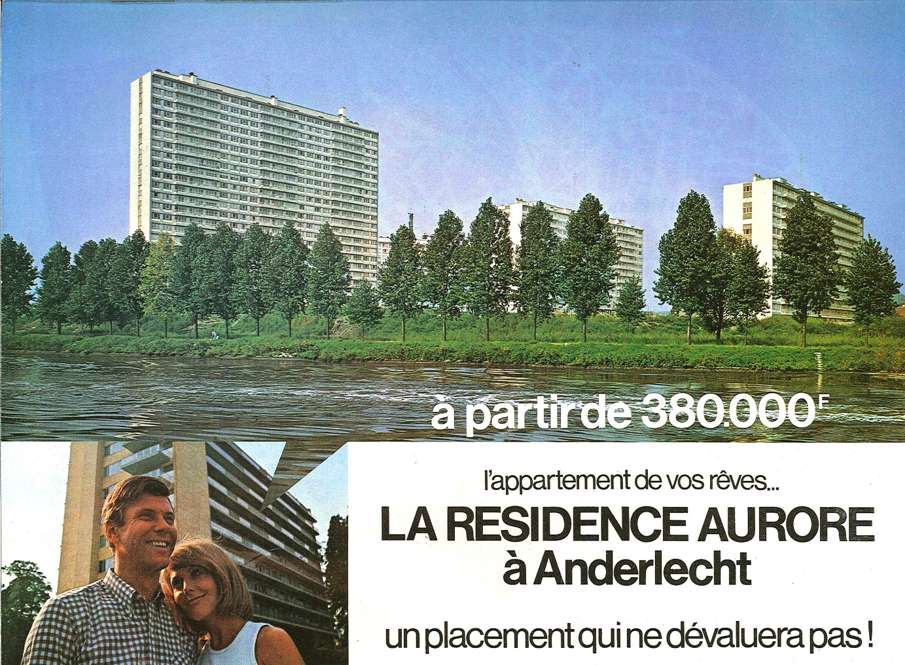

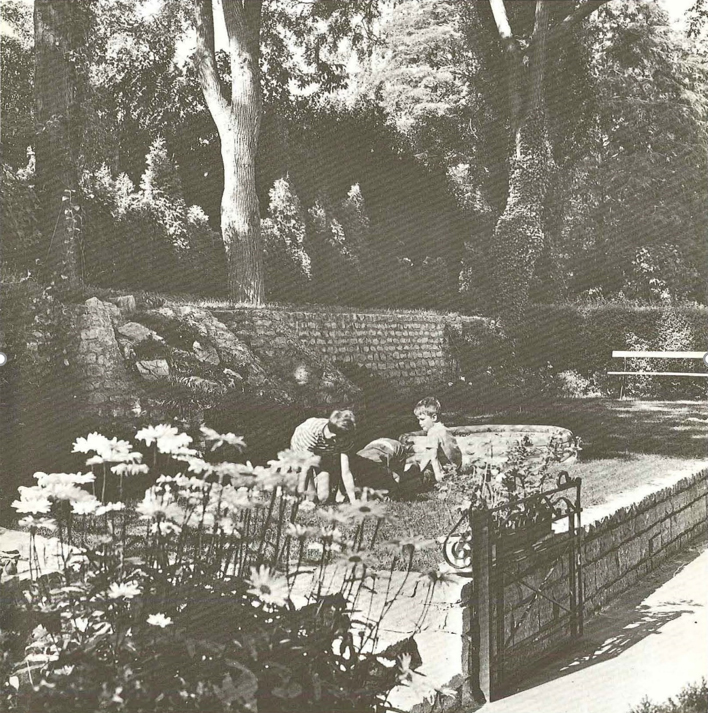

As mentioned above, Collin portrayed his ideal family as living in a park. “A green setting” and “living in a park” are recurring Etrimo sales pitches (figure 7). In the sales brochures, the project even invites potential buyers to come and have a good time with their children in the parks of residences already built. It is worth noting that each Etrimo estate is named after a park: “Parc Albert” (Ganshoren), “Parc de la Héronnière and Parc Beaulieu” (Auderghem), “Parc Schuman” (Woluwé-Saint-Lambert), “Parc Aurore” (Anderlecht), and “Parc Aristide Briand” (Woluwé-Saint-Lambert).

Children are never mentioned in the flats’ descriptions but they appear in discussions of the safety of playgrounds or entranceways. These children are still young and enjoy the outdoor green spaces (figure 8). In the words of Etrimo, “the wide avenues carry only local traffic and are pleasant places. Children can move around and play safely.” Also, “the building has wide terraces that allow the occupants to enjoy the park and parents to watch from their flats their children playing in the specially designed areas of the park. They can play without constraints, just as their parents can give them extended breaks without risk or worry.” We can see the park as a spatial support for the new civilisation of leisure advocated by Etrimo.

The recurrent organisation of “buildings in a park” recalls both the Modernists’ principles of functional urbanism (separation of cars and pedestrians, autonomy of buildings in relation to roads, “sun, space, greenery”), and culturalist urbanism led by E. Howard and R. Unwin (park system, living in the green crown of the city, roads links by major axes). The choice of this hybrid modernism allows us to refine our understanding of the imagined community. All Etrimo’s residents were suburbanites. They lived in the green periphery of Brussels, in a park system linked by the ring road, which was then under construction. This location gave rise to a particular way of life in which the car occupied a central place (figure 9).

C. Collective amenities

Etrimo organised several common spaces and amenities at various (interlinking) scales, the park being the largest scale of repetition and the building the next largest. Within buildings, each pavilion had a specific management system, caretaker, entrance, and address; there was still a sense of community within the building.

Etrimo’s brochures advertised these amenities as selling points: car, bicycle, and motorbike parking (Etrimo, 1965a); well-served environments where “flats are built in privileged locations: direct communication routes, numerous and frequent means of transport that are easily and quickly accessible” and close to schools and shops (Etrimo, 1963, p. 16); common areas “contributing to the eminence of the building”: the porch, the entrance hall, the lobbies, the lifts, the concierge (Etrimo, 1949), etc. A reading of the plans reveals that a pram room was also planned on the ground floor as well as a communal drying room on the top floor, which is not mentioned anywhere else (figure 10). Nothing is said however about the commercial premises on the ground floor or the layout of the parks.

3.2. From a trademark to a contemporary community

Not all of Etrimo’s ideas and ambitions were equally successful. While some have disappeared, others continue to support community development.

A. The recognition of an Etrimo identity

The first is a community-shared recognition of Etrimo housing estates, at the scale of the Brussels-Capital Region. Indeed, most of the interviewees knew Etrimo’s history, of its project to provide access to property for the middle classes, and of its bankruptcy at the end of the 1960s. Some could even position their building in the chronology of this history. It should be noted that this knowledge seems to be limited to Etrimo post-war collective buildings. Etrimo’s interwar buildings as well as its post-war individual houses are usually forgotten. Most residents had no idea that the housing allotments built next to their buildings were also part of Etrimo’s development. Nevertheless, a majority of residents could name at least one other Etrimo estate in Brussels and could explain the builder’s social project.

We notice an interesting reciprocal relationship: Etrimo had based their project on a community of typical households (they had therefore imagined this community) and the inhabitants also position themselves in relation to a community of buildings built by Etrimo. In their own way, they have appropriated the Etrimo community.

“Very paternalistic…Etrimo was really part of Brussels. Here we used to talk about it because these were the last buildings, then it went bankrupt. I think it was the last one here. It wasn’t built well, it wasn’t made like the other buildings, well maybe the plans and everything but the quality of the materials not so much… They were really bankrupt. I was told, but I don’t remember by whom, that the people had to do the finishing touches themselves.” Ganshoren, Mrs M, 70 years old, arrived 1972

The comparison between the two main post-war real estate developers, Etrimo and Amelinckx, is also part of a shared myth: some residents claim that Amelinckx’s buildings are better than Etrimo’s. The inhabitants are also aware of Etrimo’s bankruptcy at the end of the 1960s and the fact that many buildings or building plots were taken over by Amelinckx. They know the difference between the buildings built by one developer and the other.

“Etrimo, it was our youth. It was everywhere, everywhere, everywhere, everywhere, all over Brussels, there was Etrimo (…). And there was also Amelinckx who built. But Amelinckx was a little better and more expensive, too.” Ganshoren, Mr and Mrs G, 82 and 86 years old, arrived 1988

“Here, the concrete, the frame of the building would only be guaranteed for 30, 40 years. So it would have been finished about 20 years. Etrimo was not the best quality. Amelinckx was already at a higher level.” Ganshoren, Mr and Mrs D, arrived 1966, bought off-plan in 1964

“Here, when it was this building, Etrimo went bankrupt when it was three quarters done, they went bankrupt and then it was Amelinckx who took over... Because the blocks in the park, the ones with the red brick, that’s Amelinckx, there is a difference. There’s also a difference, I’d say, even internally, it’s richer... And then here, I think it was Amelinckx who finished the building.” Auderghem, Mrs T, 75 years old, arrived 1995

Finally, the interviewees displayed a very precise vision of what constituted the Etrimo-built community by being able to position themselves within the park, the buildings, and the pavilions. Indeed, to present their dwelling, residents position themselves in relation to the whole estate. They are thus in “the first or the last building built”, the most off-centred, the tallest or the shortest. They live at the fronts or the backs of the buildings. Some take advantage of the morning sun and others try to protect themselves from the afternoon sun. Once again, these comments make it possible to identify several sub-groups.

“My building is the shortest building. This one has only 12 floors. Over there, it’s 14 or 16 floors.”

“We are at the front of the building, so we have more work to do. All the dust, the dead leaves, the snow, it’s always at the front of the building that there is the most work.” Woluwé, Mrs I, 62 years old, caretaker since 1996

“I have the sun in the morning and it’s nice because in the afternoon on the terraces, on the other side, we can’t enjoy the terraces. From 1.30 pm until 5.00 pm, you can’t even walk on the tiles because it’s so hot on the other side.” Mrs V, 59 years old, arrived 1976

B. Oases of peace

Currently, parks with their green spaces, playgrounds (when preserved, i.e., basketball court and sandbox in Auderghem), their small facilities (former sales pavilion in Ganshoren, given back to the municipality, which turned it into a nursery), are one of the support spaces most mentioned by the inhabitants, caretakers, and pharmacists. They appreciate them in terms of aesthetics, shade, and calm (figures 11; 3b).

According to the caretakers, there are more and more dog walkers in the park. Residents are getting older, losing their spouses, and adopting pets. Etrimo’s residents meet and get to know one another, as well as people living in the surrounding areas, this way. We could say there is a “dog walkers’ community” and that the park is a support for this community. This resident remembers that the inhabitants knew each other because of their dogs and testifies to a certain mutual aid in this respect.

“There was always a cocoon here, Mum was known for babies and then we had a dog and (…) people knew him because he never listened, he was a hothead and my father always had the art of letting him loose in the park...And then sometimes, my father would say, Have you seen Bel? Oh, we put him in the lift, he’s already gone home. They’d ring my mum’s doorbell, We’ll send Bel to you! OK! And they put him in the lift.” Woluwé, Mrs V, 59 years old, arrived 1976

C. Building collectiveness

Collective basements and drying rooms on the top floor still act as community supports. Both allow the passage from one pavilion to another when a lift is out of order. In Auderghem, Mrs T, 75 years old, goes through the basements to fetch her son’s dogs from the next pavilion to avoid running into other animals. In Ganshoren, the drying rooms are even used for neighbourhood parties. In other buildings, some residents continue to use them to hang their laundry (sheets and anything that takes up space).

Unfortunately, the lack of light (there is no opening to the outside), their configuration (long and intersecting walls) and the successive deterioration of the spaces mean the drying rooms are not very useful. Faced with a collective desertion of the drying rooms, some buildings in Woluwé even decided to rent the spaces to a telephone operator to install antennas.

At the foot of the buildings, private open terraces formed by a continuous portico also constitute an interesting community space. They give a specific aspect to each building thanks to the inhabitants’ appropriation (gardening, flower pots, decorative objects, garden furniture, etc.) and “good maintenance” by caretakers. They are also a space for conviviality. In summer, those seated on the terraces invite other people to come and have an aperitif. Most of the neighbourhood parties take place on the terraces on top of the car parks, which are requisitioned for the occasion (figure 3a).

The services located on the ground floor of the buildings play a role in the social links between neighbourhood inhabitants. In Ganshoren and Woluwé-Saint-Lambert, pharmacists arrived when the buildings were built. In the first case, the original pharmacist’s son is now the owner. In Woluwé-Saint-Lambert, two young pharmacists have joined forces with the former owner. This continuity has made it possible to establish and maintain friendly and trusting relationships. The pharmacists, some of whom have known the inhabitants for many years, offer delivery of medication for those with limited mobility.

Other services occupy the ground floors. All of them are related to the medical and care field (physiotherapists, pedicurists, doctors), revealing the over-representation of people over 65 years of age compared to the regional average.

This explains the importance of the personal assistance services, associations for the elderly, and activity clubs present in these municipalities. These places provide important sources of support for the elderly. Many people told us that they missed the activities, outings, and events organised by community centres, associations, and cultural venues (suspended during the pandemic).

Other places originally frequented by Etrimo residents have now disappeared. These include local shops (butcher, baker, haberdasher, grocery) whose evolution, although varying according to the municipality, is moving towards total disappearance. Carrefour Markets and Proxy Delhaizes have taken over. These transformations raise questions about the evolution of community-support spaces and the renewal of the community/ies themselves.

At pavilion level, we note the unifying role of the caretaker. In Ganshoren, Mrs N created a Facebook page for the pavilion to communicate with the residents and to facilitate exchange (of furniture in particular). Mutual aid exists on this scale for shopping, exchanging meals, watering plants, and looking after animals. In Woluwé-Saint-Lambert, the caretaker, Mrs T, is in charge of organising the neighbours’ day:

“The only thing we do collectively is the neighbours' day, normally in May, but given what’s going on (with the Covid19), we haven't been able to organise it. So that’s it. We do it here in front, we put tables. We put tables here in the hall and the people are there, in front and what we do is we put ribbons, so that the cars pass by the back because the children, they play. And even people from other buildings come too (...). I have someone who helps me to do it. I have a lady here who helps me to put out the tables. She's a lady who gives me a big folding table that she has at home and then we put it there. And she brings the chairs down and the other people bring chairs down. I usually go shopping with the president of the building, we always take a little bit to start with, but otherwise, people bring a little something each. It has always gone well.” Woluwé, Mrs T, 70 years old, caretaker, arrived 1996

When discussing the pavilions, no one uses the names of flowers or shrubs given to each building, and few use addresses (street numbers). They are more likely to use the pavilion number, which refers to the order of construction over time (pavilion 1 being the first built). This naming system reinforces the idea of mutual recognition and inhabitants’ common belonging to the Etrimo park.

Inside a pavilion, the inhabitants recognise that their encounters are conditioned by the times at which they go out and come back (especially those who work) but also by the floor number, even or odd, that they live on and the use of the appropriate lift.

“As there are two lifts, one even and one odd, there are always some of the people we know much less because we don’t all see each other at the same time.” Auderghem, Mrs T, 75 years old, arrived 1995

“I know everyone, but what happens is that people know each other more on the odd and even sides because, as it’s two different lifts, they hardly ever meet.” Woluwé, Mrs T, 62 years old, caretaker since 1996

The caretakers of each estate form a group in their own right, although the collective understanding and organisation varies site to site. In Ganshoren, for example, most caretakers share the weekend on call. They share chores such as washing garages or taking out garbage.

“This weekend I’m on call. It’s a weird thing to be on call here. If there’s a leak on the other side, it’s me, my number’s there…. But I say, if there’s a problem, the person should call the plumber straight away! That’s the way it is from Saturday 8 am to Monday 8 am.” Ganshoren, Carla, 50 years old, arriving from Portugal in 2019

“The caretakers are together but separate. She has her lodge, I have mine, she has her gallery, I have mine, she has her routine, I have mine, we don’t mix. If there’s a problem, we call each other, can you help me, and there it is, there was a stuck door, I went to help her, we help each other if there’s a problem, I know I can count on her, if there’s a problem, we help each other, it’s easier. But she has her job and I have mine.” Auderghem, Maria, 49 years old, arrived 1994

Neighbours who share a landing usually know one another, such as two neighbours who wanted to answer our questions together or another who has made friends with her young neighbour. This proximity was rarely mentioned as a problem, since noise pollution, for example, comes more from the floors above. However, the landing, because of its narrowness and lack of natural light, is not exactly a relational support area either (we did not observe any plants, or any decoration of the entrance halls).

“My neighbour is a cook and as he is unemployed at the moment, he said to me, Listen, if you ever want to have a good meal, I’m ready to do it (...) And then, the landing here is fantastic, I must say, we are very spoilt. Across the landing, there’s also a lady who arrived alone shortly after me. So that’s great. If we all had landings like that...” Ganshoren, Mrs S, 80 years old, arrived 1990

“I'm old now and automatically I have my neighbours on the landing who are much younger and automatically when they see me, they say to me, If you need anything or if there’s anything, we’re here.” Auderghem, Mrs T, 75 years old, arrived 1995

4. Contemporary challenges for the Etrimo community

In the three Etrimo estates studied, recurrent trends were observed, relating to the sense and the formation of an inhabitant community and the potential of some community supports.

4.1. From a homogenous community to several sub-communities and spatial supports

We have seen how, in Etrimo’s ideology, the juxtaposition of identical households may have produced a homogenous community based on middle-class families. Family compositions, residential strategies, and even ways of life were similar amongst residents. Some members of this initial community are still present in Etrimo settlements, but they constitute a minority.

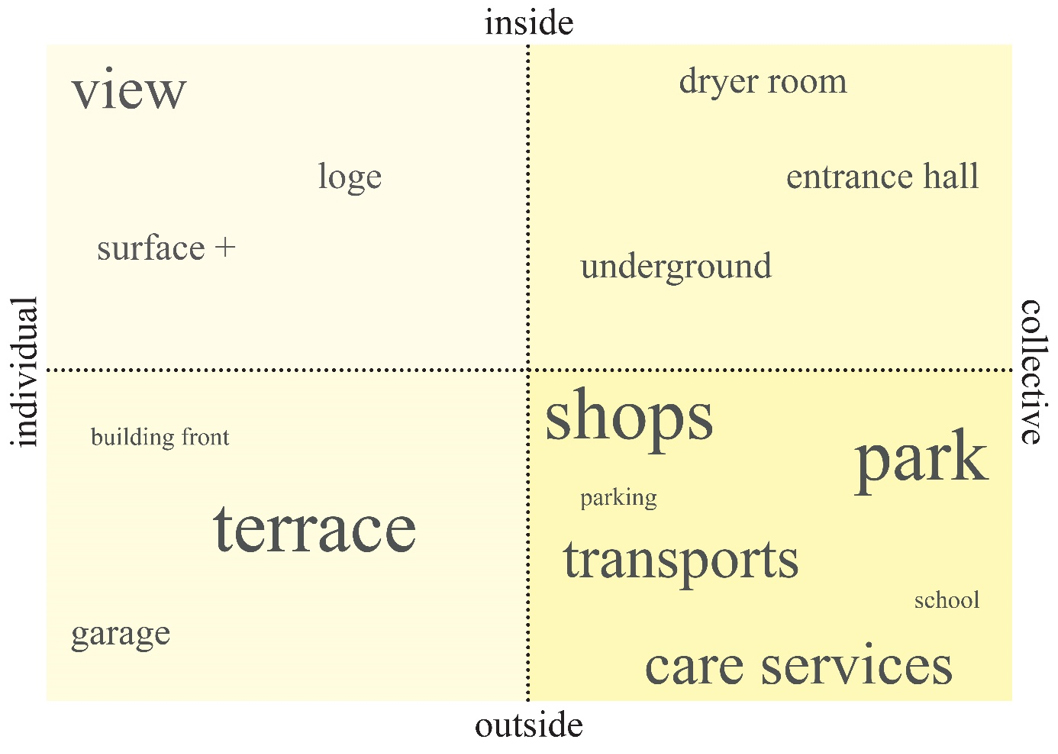

Today, Etrimo settlements are no longer characterised by this homogeneous population. Rather than a homogenous community, we found various inhabitant communities. Their existence is motivated by social and spatial reasons. On the one hand, there are communities built through sharing an identical vision of collective life (the older generation), a common activity (dog walking), a certain relationship with the condominium (the caretakers), or a family link. On the other hand, spatial proximity (shared landing, lift, pavilion, etc.) as well as the characteristics of certain spaces (entrance, collective drying room, foot of the building, park) contribute to the constitution of other groups. Accordingly, we could say that some spaces support the creation of collective dynamics. Figure 12 synthetises this capacity: it highlights the spaces most mentioned by the inhabitants as contributing to the establishment of communities. These spaces are categorised in four groups defined by two axes, the social, horizontal axis and the spatial, vertical axis, for instance:

(1) individual interior spaces: the view from the flat (and location within the estate as a whole) promotes the establishment of sub-groups at the front or the back of the buildings;

(2) individual outdoor spaces: the terraces that, with their blue balcony ceilings, orange awnings, and railings, characterise Etrimo buildings and participate in the construction of an Etrimo community at the city scale;

(3) collective indoor spaces: the entrance hall with the presence of the caretaker, letter boxes, lifts, is a very important place that allows mutual recognition among pavilion residents;

(4) outdoor collective spaces: the proximity of shops and health services are often pointed to as places where residents meet, supporting yet again another form of community. As noticed across all the communities, these shared shopping practices often lead to mutual aid and solidarity among residents (e.g., sharing shopping).

4.2. From a life project to a stage in a residential journey

The reduction of owner-occupiers has led to increasing residential turnover. Two trends can be noted: first, the estates’ population are getting younger. Whereas the 1990s and 2000s were marked by an overwhelming proportion of elderly people (the newcomers were then aged between 60 and 80), for the last ten years or so, the housing estates have been getting younger (departure and death of the oldest residents, arrival of young households). Second, some residents move in for specific periods of time depending on their professional circumstances (employees of the European institutions in Woluwé). Therefore, for them, Etrimo corresponds to an intermediate stage in their residential journey, a transitional moment in their lives. That is very different from the initial situation imagined by Collin. This evolution influences the relation to the community. The new inhabitants have a more consumerist relationship with their housing. They buy or rent a product that suits them at a given moment in their lives and which they will get rid of when they no longer need it. The interest they find in it is related to the low price and the proximity to their work. But they have no interest in getting involved in the collective life of the place. The common services are options that they pay for (the caretaker, for example). In this respect, they rarely or irregularly get involved in the management of the co-ownership, which are supposed to be the responsibility of professional structures. The distance they keep from other residents gives them the illusion that they remain free to leave at any time. This attitude is very different from that of older people who have “always lived there”.

4.3. New challenges to shape new communities tomorrow

New opportunities nevertheless allow us to imagine new communities. These opportunities take the form of at least four common challenges: building renovation, soft mobility, parks renewal, and evolution of the caretakers’ role.

Concerning building renovation, challenges arise such as lowering energy consumption, renovating terraces and facades, replacing railings and blue balcony ceilings. In this case, older people are reluctant to sacrifice their peace and money for changes that they are unlikely to benefit from. Younger households, however, seem to be more concerned about the rehabilitation of buildings.

Concerning mobility, we observed that these initially suburban estates were designed for the car generation. Nowadays, they are extremely well connected by public transport (metro, tramway, several bus lines). For the public authorities, as well as for future Etrimo inhabitants, it could be interesting to reflect on the challenges posed by soft mobility in these neighbourhoods. At present, there is very little space to park bicycles or prams, for example. This topic could bring together groups of young residents.

A similar reflection applies to the maintenance of the parks (currently closed to games) and the invention of new social practices. In addition, the parks created by Etrimo in the city’s second belt create an oasis of nature and peace that could help us envision the green city of tomorrow.

Finally, the issue of caretakers and their maintenance or replacement by outsourced services (cleaning company) or even virtual services (video surveillance, switch to connected intercoms in the halls), is also a challenge to be tackled by today’s residents. It could be an opportunity to work together on other ways of maintaining and ensuring the smooth running of the community.

These new challenges are central issues to our society. What if the Etrimo community could seize them to reinvent itself?