1. Introduction

This article deals with the relationship between creative activities and urban space in a comparative perspective between two neighborhoods recognized for their creative dynamics, located in two Brazilian metropolises: Botafogo (in Rio de Janeiro) and Santa Tereza (in Belo Horizonte). The purpose of this article is to analyze how social, economic, cultural, institutional, and urban attributes condition the development of the creative economy in the aforementioned neighborhoods, forming districts marked by clusters of creative professionals and businesses.

The interest in the relationship between creative dynamics and urban space has grown significantly. For instance, Costa and Lopes (2013; 2015) have analyzed cultural districts in ten cities, attesting that artistic and cultural interventions make these places more dynamic. The interaction the resident communities have with these interventions revealed multiple layers of uses, symbols and underlying segregations, while also showcasing the interventions as a valuable practice to revitalize the routine in these urban spaces.

Based in studies on productive clusters and cultural quarters, we used references to understand the evolutionary dynamics of cultural and creative clusters, with special interest in the ones created in certain areas of a city, where production and consumption of culture contribute to economic development and to the symbolic makeup of these places.

To that end, we carried out a qualitative exploratory research, using the following methodological procedures: semi-structured interviews with entrepreneurs professionals, and public authority managers to understand the clusters’ cultural and institutional trajectories; and urban landscape photographic analysis to identify the neighborhoods’ urban outlines, specially built form and presence of meeting and gathering spaces (Montgomery, 2010), as well as their uses and conflicts pertaining to the creative economy.

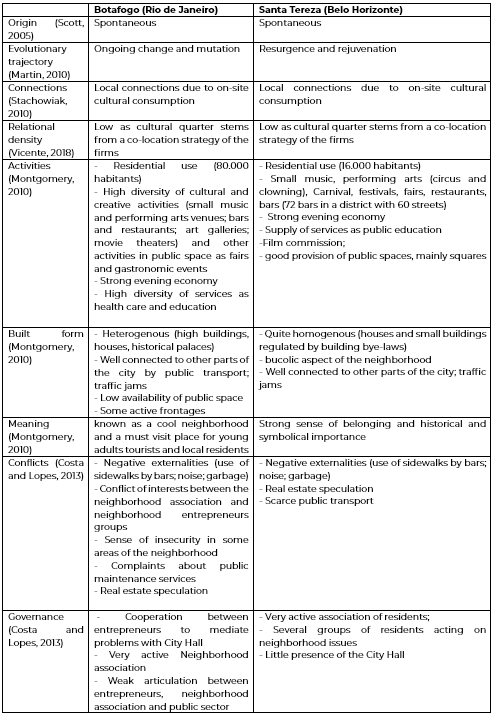

Botafogo and Santa Tereza are traditional neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro and Belo Horizonte. Both stand out in their respective cities’ creative ecosystems. Considering the range of creative activities, it is possible to find different types of clusters according to their economic specialization. In our case studies we are interested in clusters formed by cultural activities thar are on-site consumption, as traditional culture expressions, live music, theatre, clowning, carnival, and gastronomy. However, their development of creative activities is different: Santa Tereza has greater historical and symbolic recognition than Botafogo, which is undergoing a more recent process of creative development, due to its social and economic characteristics. The research results indicate that cultural and creative districts can be formed through different processes and that interactions between firms vary according to the nature of the activities and the perception of benefits. The institutionalization of governance mechanisms need to be improved to mediate some conflicts in favor of the sustainability of the cultural quarters.

This article is organized into five sections: introduction; literature review; methods; results and discussion; and concluding notes. Focused on the urban microscale, this research is expected to contribute to the generation of knowledge applied to urban planning.

2. Creative dynamics and urban space: clusters and conflicts in the use of urban space

Creative activities are not homogeneously distributed across space, thus forming geographic clusters identified by clusters of firms and specialized workers (Scott, 2005). Consequently, studies on the creative class (Florida, 2002), creative cities (Landry, 2008; Vivant, 2009) and, especially, on the forces that condition the cluster of creative activities in space (Lazzeretti, Boix & Capone, 2013; Komorowski & Picone, 2020) emerged with the aim of understanding the phenomenon of spatial concentration and its consequences and opportunities for urban planning and regional development.

In seeking to understand the origin and consolidation dynamics of clusters, Scott (2005) acknowledges three phases in its development.

“The first phase involves an initial geographical distribution of production units over the landscape, possibly at random, possibly as result of some preexisting geographic condition. The second and more important phase begins when one particular location starts to pull ahead of the others and to form a nascent agglomeration. This turn of events again can be result of purely random process, or may stem from some peculiar conjuncture in the agglomeration’s development logic (…) A third phase can be identified (…) in which the agglomeration, building on its intensifying competitive advantages, extends and consolidates its market reach, while other locations enter a period of comparative stagnation or decay” (Scott, 2005, p. 16)

According to this evolutionary perspective of clusters1, the second phase is the most important because it is the period when there is a rupture or a bifurcation in the trajectory of a given sector, which from then on starts to cluster in a given location. The phases do not have a predetermined duration and their results are not static, hence new ruptures or bifurcations may occur. The second phase is driven by the increasing returns that generate positive feedbacks, which, in turn, reinforces spatial concentration. Arthur (1990), recognized for being one of the first to try to characterize a cluster as a dynamic process that generates a locational pattern, explains this dynamic of locational choice.

“Suppose that firms enter an industry one by one and choose their locations so as to maximize profit. The geographic preference of each firm (the intrinsic benefits it gains from being in a particular region) varies; chance determines the preference of the next firm to enter the industry. Also suppose, however, that firms’ profits increase if they are near other firms (their suppliers or costumers). The first firm to enter the industry picks a location based purely on geographic preference. The second firm decides based on preference modified by the benefits gained by locating near the first firm. The third firm is influenced by the positions of the first two firms, and so on. If some location by good fortune attracts more firms than others in the early stages of this evolution, the probability that it will attract more firms increases. Industrial concentration becomes self-reinforcing” (Arthur, 1990, p. 95).

It does not matter whether the first locational decisions were made in terms of existing factors or random events. The fact is that, with each new unit in the system, the choice becomes progressively less random; and the new unit is more likely to choose a location already taken by other firms, as a result of the cluster economies in that location. Thus, Arthur (1990) stresses the importance of random events and path dependency in the formation of clusters.

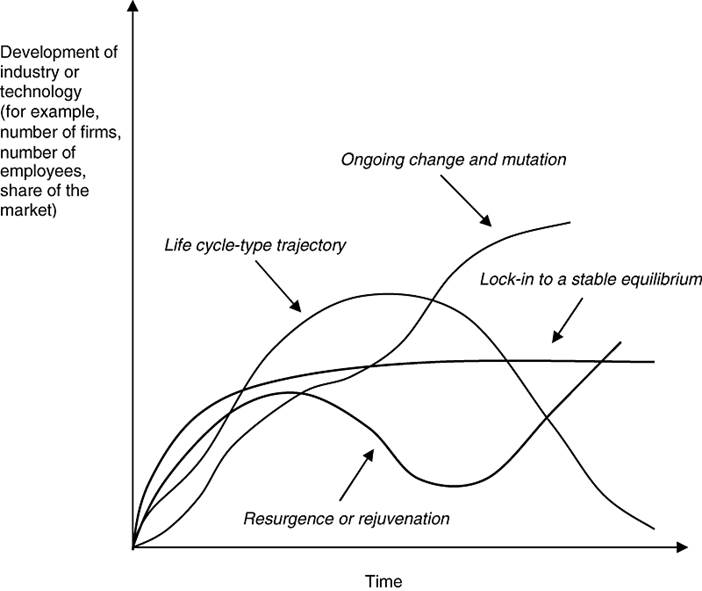

Martin (2010), in turn, argues that the view of path dependency in Arthur's theory (1990) leads to a lock-in phenomenon, which in the end represents a stable equilibrium in the long run. The development dynamics of a cluster, therefore, in addition to being represented in a lock-in conception, must also consider other types of trajectories, such as life cycle, resurgence or mutation.

“We know, for example, that many industries and technologies trace out some sort of “life-cycle” pattern over time and that the shapes of these patterns vary markedly from industry to industry, from one industrial district to another, and from one business cluster to another, while still others follow a pattern that involves path renewal or rejuvenation or even more or less continuous change and mutation” (Martin, 2010, p. 9).

When dealing specifically with cultural and creative clusters, Stachowiak (2020) points out that this approach presents great diversity in terms of geographic scale and its connections, which can be more local or supralocal. The debate about scale refers to the distance in information, transactions and interactions between firms and workers, with more globalized activities (i.e., those in which the market reach is more global), tending to cluster more than activities whose market reach is more localized. We can thus identify cultural and creative clusters whose interactions occur in transnational, national, and regional scales at the city-region, neighborhood and sub-neighborhood levels (e.g., co-working spaces).

Another important attribute is the nature of the activities located in cultural and creative clusters, which can be understood by the notion of co-location or co-production (Stachowiak 2020). In other words, it is important to know if firms share the same location in search of locational benefits, but do not have productive interaction dynamics, or if, in addition to geographical proximity, firms also interact productively.

The development trajectory of a cluster may not be dependent on interactions between firms. In managing the production of knowledge about a given activity, firms' choices between cooperating or competing are impacted by the dilemma between appropriating internally generated knowledge or seeking access to external knowledge (Vicente, 2018). In this perspective, cooperation will only occur when firms perceive more benefits in mutual access to external knowledge than risks of under-appropriation of the benefits of internally generated knowledge.

“When the development of a market relies on a knowledge from different industries, relational density can be expected to increase as each organization seizes opportunities from their technological complementarity. Conversely, the co-location of organizations operating in the same market can limit collaborations because of a strong capacity of knowledge absorption from one actor to the other. In this case, they benefit from localization externalities such as a local labour market, the presence of universities, and specialized services, but, at the same time, they limit the risks of under-appropriation by maintaining a relational distance within the cluster” (Vicente, 2018, p. 59)

When cooperation occurs and the relational density of the cluster increases, the institutional environment becomes decisive for shaping interactions between firms, as institutions are determinant for social, political or economic interaction and for economic performance (North, 1990).

“There may well be accidental factors that initiate specialization, and there are certainly circular and cumulative agglomeration processes. But in the long run, capturing, creating, and regenerating specialization successfully requires existing networks of actors, as they are the basis of the functioning of the formal institutions of metropolitan government and governance, and they themselves amount to informal institutions that carry out the mobilization and transposition of skills and capacities across different domains of the economy as well as time periods” (Storper, 2013, p. 103).

In urban planning, studies on the cluster dynamics of cultural and creative activities in certain areas of cities have been developed with special interest in how the formation and development of cultural quarters contributes to the local economy and to urban restructuring processes. According to Montgomery (2003), most large cities have identifiable cultural quarters to which cultural and creative entrepreneurs are attracted. The author adds that these are areas with an important history in the development of the city, which seem to have developed by accident or as a consequence of the city's own development. The novelty in studies of cultural quarters is that they have recently come to be used as an urban restructuring mechanism applied in degraded areas.

“A cultural quarter is a geographical area of a large town or city which acts as a focus for cultural and artistic activities through the presence of a group of buildings devoted to housing a range of such activities, and purpose designed or adapted spaces to create a sense of identity, providing an environment to facilitate and encourage the provision of cultural and artistic services and activities” (Roodhouse, 2010, p. 24).

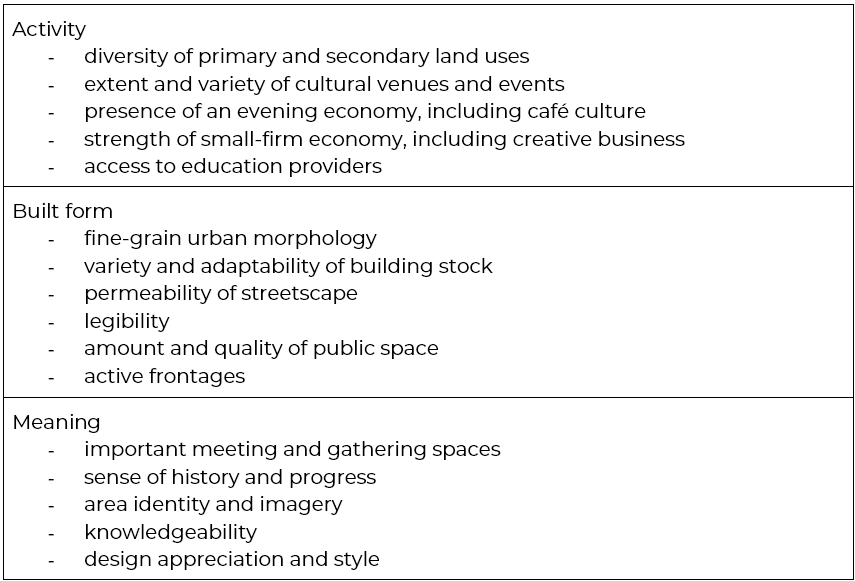

Hence, cultural quarters are not only the result of urban forms and functions located in a given area of the city, but are also determined by the symbolic contents they communicate. Therefore, the analysis to characterize a cultural quarter and identify its uniqueness requires the ability to compare the various existing cultural quarters, to verify the existence of practices that can be learned and applied. Faced with this challenge, Montgomery (2003) proposes a framework with three sets of elements present in any cultural quarter: activity (economic, cultural, social); form (the relationship between buildings and spaces); meaning (sense of place, historical and cultural).

Another comparative approach to cultural quarters is provided by Costa and Lopes (2013), who investigate factors to explain the vitality and sustainability of cultural quarters. If, on the one hand, the diversity and complexity of activities are fundamental for the resilience of these territorial systems and for the development of governance mechanisms and symbolic attributes that contribute to long-term vitality, on the other hand, the relationship between characteristics of a cluster and its informal dynamics still requires better understanding. The recognition of the importance of informal dynamics changes the vision of urban planning.

“Re-thinking the city through micro-scale systems of action, instead of just large projects and flagship interventions is essential for planning the city integrating urban creativity and real creative dynamics. Understanding everyday life and the role of more informal and ephemeral initiatives for cities’ planning is fundamental, requiring (re)focusing our attention to this specific issue and the use of new methodologies” (Costa & Lopes, 2013, p. 42).

Hence, to understand the interaction between the more traditional factors in the development of cultural quarters with their informal dynamics, Costa and Lopes (2013) have proposed 9 dimensions to address the vitality and sustainability of these spaces: 1) dimension, density, and heterogeneity; 2) symbolic capital; 3) physical/symbolic centrality in the city; 4) morphology; 5) conviviality and nightlife; 6) art world’s reputation mechanisms; 7) main use conflicts; 8) informality/public sphere appropriation; 9) specific governance mechanisms.

The complexity of this approach has the potential to contribute to urban planning policies not exclusively centered on large projects detached from the local dimension of culture and everyday life. Urban life promotes unforeseen encounters and experiences, calling the urban planner to think modestly, with humility, for creativity is not planned or programmed, it arises from the unforeseen and the unexpected; it is born in unexpected places, as a result of the friction between otherness and unforeseen encounters (Vivant, 2009).

3. Methods

With a qualitative approach, an exploratory research was conducted to analyze the ways in which social, economic, cultural, institutional, and urban attributes condition the development of the creative economy in the neighborhoods of Botafogo (in Rio de Janeiro) and Santa Tereza (in Belo Horizonte), thus forming districts marked by clusters of creative firms and professionals.

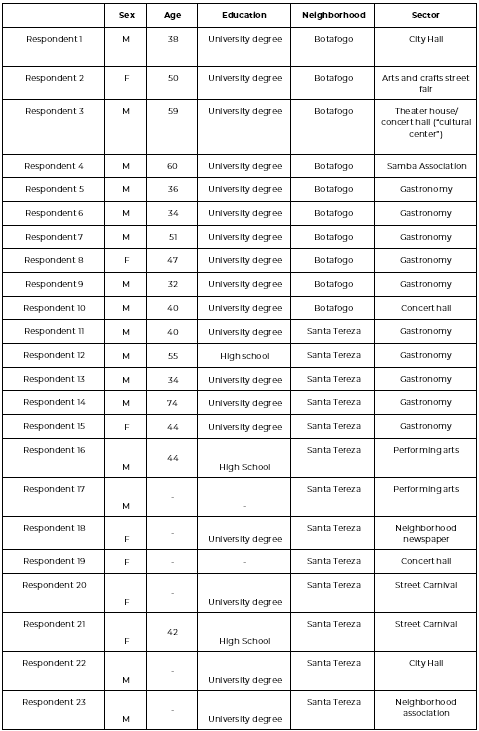

For this study, the following methodological procedures were adopted: semi-open interviews guided by a script of semi-structured questions (Duarte, 2006) carried out with: (i) business people and entrepreneurs linked to the creative economy and, more specifically, to spaces of cultural enjoyment; (ii) representatives of neighborhood associations and local/municipal public authority managers. This selection is intended to ensure the representativeness of businesses linked to the creative economy in the neighborhoods, considering as the main criteria the recognition of historic and economic role of each one in the clusters’ dynamics. Regarding the interviews with local/municipal public authority managers and neighborhood associations, we selected the ones more involved in the relationship between entrepreneurs and residents. The interviews were mostly carried out in person, but of the total of 23, five were carried out online, via Zoom.

The interviews were coded and themed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) - a flexible analytical method that can be employed in different types of research and with different research questions, in addition to allowing for the analysis of data sets (originating from interviews, focus groups or other texts) to find repeating patterns of meaning. In the interviews with entrepreneurs, five themes were analyzed: the business and the circumstance of its foundation; the choice of neighborhood; the perception of the neighborhood; the relationship with other businesses and with the public authorities; the relationship with the neighborhood.

As for the interviews carried out with representatives of local associations and public authority managers, four themes were analyzed: the public authorities’ view of recent urban, economic, social, and cultural transformations in the neighborhood; the role of government bodies and public institutions in the neighborhood; the relationship with entrepreneurs and their associations, with cultural organizations and neighborhood associations; the public authorities’ projects and plans for the neighborhood. Table 2 indicates the profile of respondents.

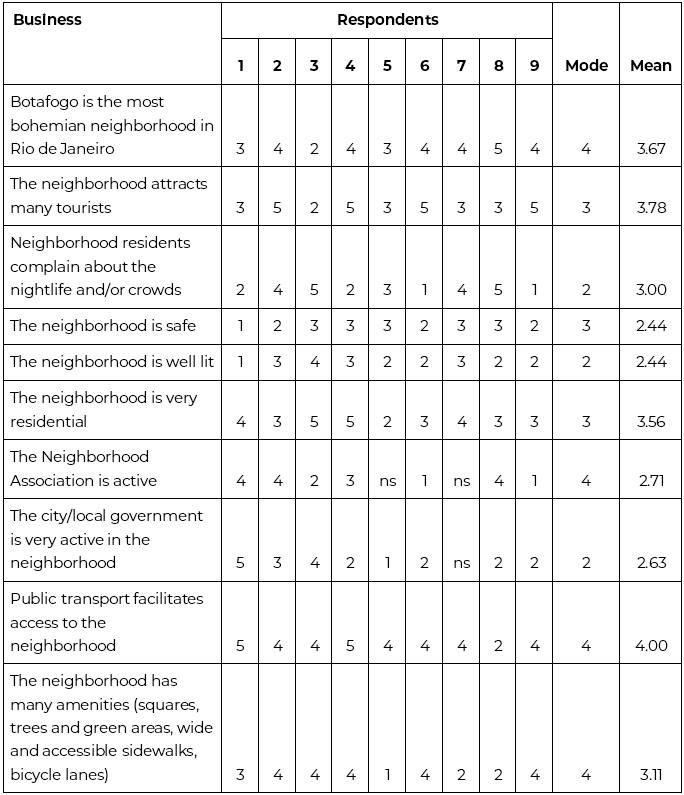

An urban landscape photographic analysis was carried out to identify built forms of the neighborhoods and their uses and conflicts related to the creative economy, according to Montgomery (2003). In addition to the photographic and thematic analysis, a table was created based on the perception of the respondents in the first group regarding aspects of the neighborhood. On a scale of 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), the respondents were asked to rate aspects of the neighborhood according to the following statements:

Botafogo/Santa Tereza is the most bohemian neighborhood in the city of Rio de Janeiro/Belo Horizonte

The neighborhood attracts many tourists

Neighborhood residents complain about the nightlife and/or crowds

The neighborhood is safe

The neighborhood is well lit

The neighborhood is very residential

The Neighborhood Association is active

The city/local government is very active in the neighborhood

Public transport facilitates access to the neighborhood

The neighborhood has many amenities (squares, trees and green areas, wide and accessible sidewalks, bicycle lanes)

In the case of Belo Horizonte, the UNESCO “Creative City of Gastronomy” seal contributed to the success of your business

The Likert Scale is a measurement method that seeks to assess people's opinions and attitudes, allowing for qualitative aspects to be measured quantitively. Thus, the mean and mode of responses were calculated. Despite having a subjective character, as it refers to the respondent's perception, the indicator contributes to reaching people's motivations to establish creative businesses/enterprises in the neighborhood.

4. Results and Discussion

In order to examine and compare the two neighborhoods, this section presents the results referring to each neighborhood, considering: i) a brief description of the neighborhood with analysis of the photos; ii) impressions of the public authorities and the respective neighborhood association; iii) thematic questions according to interviews conducted with the firms and businesses; iv) perception of the firms and businesses.

4.1 Botafogo

Located in the southern zone of the city of Rio de Janeiro, the neighborhood of Botafogo has a population of over 80,000 inhabitants2, currently occupying the tenth position among the 158 Rio de Janeiro neighborhoods tracked by the Social Progress Index (IPS) ranking3, behind the neighboring districts of Copacabana, Flamengo, Humaitá, Laranjeiras, and Lagoa, but ahead of the also neighboring Leme and Urca.

Botafogo is geographically located with easy access to several points in the city, therefore presenting high movement of people during the week as well as on weekends. The significant movement of people in this region is also due to the large concentration of schools, colleges, clinics, and hospitals in the area. On the weekends, this is related to the high number of cultural spaces in the neighborhood, such as movie theaters (Grupo Estação, Cinema Itaú, and Cinemark movie theaters in Botafogo Praia Shopping), the Indigenous Museum, the Villa Lobos Museum, and the Rui Barbosa Foundation, which are spaces that offer the public collections, exhibits, and gardens. There is also the Firjan House, a space for education and creativity that offers courses and lectures, in addition to having a large preserved green area; the Poeira and Poeirinha theaters; the Companhia de Teatro Contemporâneo (Contemporary Theater Company) and the Solar Botafogo, which are spaces for performing arts, and a unit of the most important bookstore chain in Rio de Janeiro - Livraria da Travessa. Besides all the cultural spaces mentioned above, Botafogo also houses small studios, music schools, and one of the largest independent production companies, Conspiração Filmes.

In the last two decades, the neighborhood has undergone several transformations in residential, business, and commercial occupation. A recent survey (Corrêa & Dubeux, 2021) found that in recent years, new ventures linked to the creative sectors have stood out in this scenario of transformation in the neighborhood, particularly those linked to gastronomy, which represented an expressive number in the data survey conducted.

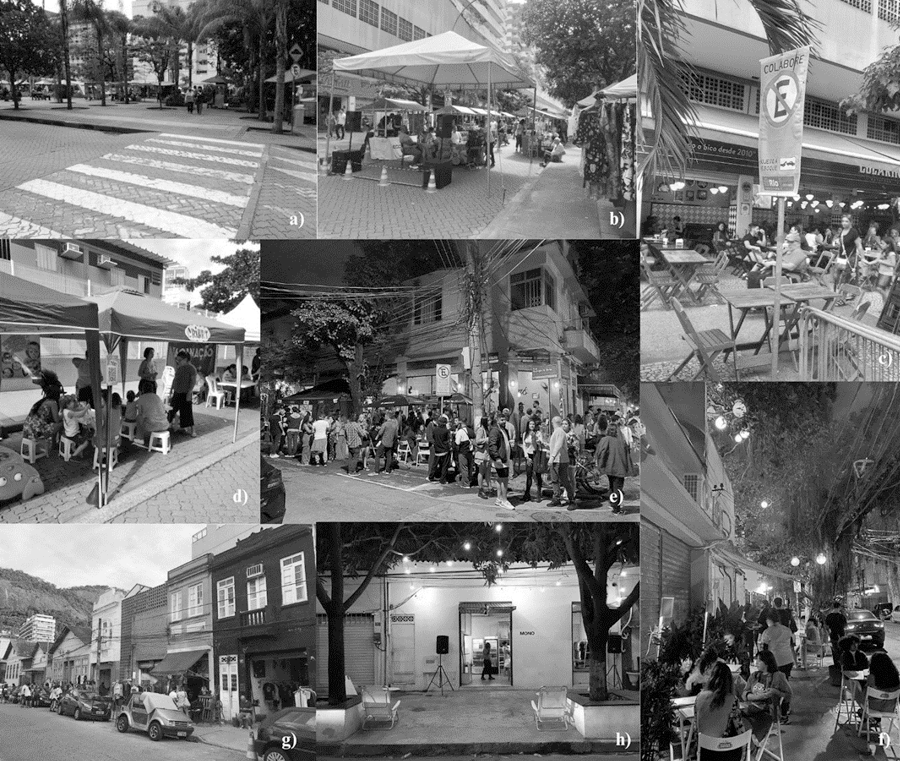

The following compilation of photos highlights some of Botafogo’s public spaces and the ways these spaces are occupied by residents, frequenters, entrepreneurs and businesspeople, and government authorities. The Nelson Mandela square and street, on regular days as well as on days when traffic is closed for the arts and crafts street fair. The presence of the municipal government is marked in the urban space via traffic signs indicating the temporary parking bans and in tents installed for vaccination campaigns. The occupation of the sidewalks by bars, restaurants, and stores, which set up tables and chairs for the use of their regulars.

Caption: a) Nelson Mandela Square (regular day); b) Nelson Mandela Square (arts and crafts street fair day); c) No-parking sign; d) Vaccination tents; e) Streets occupied by bar-goers; f) Streets occupied by bar tables and chairs; g) An event held on the street; and h) Street at night (sidewalk occupation).

Most respondents emphasized that the decision to open their business in Botafogo was largely due to the price and availability of real estate. This is a question of cost-benefit compared to other neighborhoods in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, such as Copacabana, Ipanema, Leblon, and Lagoa, which are considered prime areas, both from the residential and commercial point of view. The mobility (the subway is close by, and several bus lines serve the region) that Botafogo offers was also mentioned by the respondents as one of the decisive elements in choosing the neighborhood to install their businesses. Only one respondent, a live music venue owner, reported choosing Botafogo based on the existence of other studios and music venues in the area, such as Canecão and Hanoi, reference points in the neighborhood. According to this respondent, Botafogo is house to a cultural scene in which people linked to the arts and academia/sciences, and cultural producers circulate, as well as gastronomy entrepreneurs of what he called “a more creative cuisine.”

In the specific case of the bars and restaurants, the respondents also pointed out as reasons the diversity of people that frequent the neighborhood and the effervescence of the different gastronomic hubs in Botafogo: the one located on and around Rua Nelson Mandela, the one on and around Rua Arnaldo Quintela, and the one in the Cobal market and its nearby streets.

At the end of the day and on weekends, Botafogo’s narrow sidewalks are crowded with people going to the new and “hip” restaurants and bars that occupy wholesaler warehouses, body shops, two-storey houses, or preserved houses amidst the new real estate developments launched in recent years. The crowds that dispute the sidewalks and take over the streets are constant in the bohemian micro-regions that have formed in the neighborhood, attracting different audiences. Despite its renewal and appreciation in recent years, the neighborhood still has several infrastructure problems, especially in sanitation and safety.

As for the relationship with other businesses, the two live music venues owners had opposing views. One said he relates to other ventures in the neighborhood, mentioning the strong relationship with other studios, the sharing of information, cooperation, and the establishment of partnerships with other entrepreneurs in the music market. The other respondent, quite differently, reported not participating in any Botafogo group or association but said he is part of WhatsApp groups that bring together members of the country’s artistic and cultural scene.

The gastronomy entrepreneurs reported establishing relationships only within the industry and the neighborhood. Specifically in the area near Rua Arnaldo Quintela, which for some time was called “Soho Botafogo,” local entrepreneurs took the initiative to create a collective, although the initial idea was to create a gastronomic hub. However, as they report, it was not possible to create a new hub, as Botafogo already housed an “official” gastronomic hub in Botafogo, which is why they aborted the initial idea of calling the association a “hub,” but not the idea of a collective organization.

For most respondents, the relationship with the municipal/local government and public authorities is developed on-demand. In general, only when the business is opened because regularization actions are required, such as issuing business licenses, and when a problem occurs, such as inspections and inspections carried out due to resident reports and complaints. The respondent who organizes arts and crafts street fairs is an exception because, at each weekly edition, organizers must contact the municipal public agencies responsible for authorizing and or coordinating events in public spaces in the city. This respondent’s relationship with managers and employees of local government agencies is more frequent and closer when compared to the other respondents.

As for the public authorities’ view of the neighborhood’s recent urban, economic, social, and cultural transformations, the City of Rio de Janeiro representative interviewed emphasized the heterogeneity of Botafogo, classifying the neighborhood as the most heterogeneous in Rio’s South Zone in terms of social and economic fabric. Residential condominiums deemed “premium,” two favelas, abandoned houses occupied by drug users, large and traditional businesses, small boutiques, luxury restaurants that boast Michelin stars, and alternative bars make up Botafogo’s urban landscape. Regarding the district’s recent transformation process, which has ceased to be seen as a transit district (i.e., as a mere link between downtown Rio de Janeiro and the South Zone), now seen as a trendy, bohemian, cult, and “cool” neighborhood, he lists two main milestones: the 2009 opening of the Nelson Mandela street and square, after the subway was finished, and the moving of the Military Police battalion to Rua Álvaro Ramos, which allegedly brought more security to this area of the neighborhood. He acknowledges the existence of four gastronomic and cultural complexes: the areas of Rua Nelson Mandela, Rua Álvaro Ramos, Cobal4, and Rua Real Grandeza. In relation to the neighborhood’s power of attracting new enterprises, this respondent believes this to be a culmination of specific conditions in Botafogo: the existence of available residential and commercial spaces, the lower price of the square meter in comparison to other neighborhoods in the city’s south zone; the high purchasing power of the resident population; the public recognition of Botafogo as a trendy neighborhood, where a range of “cool” businesses already operate.

Currently, an important issue that has stood out in the neighborhood’s daily life is the increase in complaints and accusations made by residents about the developments, particularly bars and nightclubs, that do not respect the rules of coexistence. In general, these complaints are forwarded to the neighborhood association AMAB and the communication channels of the public authorities. However, some residents complain directly to the owners and managers of the developments, which leads some respondents to try to establish a closer relationship with the residents. However, this decision does not always bring significant results.

The residents’ relationship with the neighborhood has become more worrying, gaining space in the media in Rio de Janeiro. Frequent newspaper articles and features report about complaints from residents regarding noise (music), the undue occupation of sidewalks and streets with tables, chairs, and bar-goers, and the indiscriminate use of illicit drugs in front of the bars. The entrepreneurs consider the possibility of restricting operating hours for bars, but understand that banning sidewalks and streets would be a step backward for the neighborhood of Botafogo. According to them, the generation of jobs and the occupation of the locations promotes a greater circulation of workers and frequenters, consequently increasing the safety of the areas in which these businesses are located.

In the final part of the interviews, objective questions were asked on a Likert Scale in order to evaluate the respondents’ opinion and map their perception patterns about the neighborhood, covering such items as safety, lighting, transportation, amenities, bohemianism, frequency of tourists, residential profile and governmental action. This, however, was done for statistical analysis, since this is research is qualitative. We noticed a certain difficulty on the part of the respondents in objectively evaluating each of the questions, differently from the spontaneity and richness of detail that marked the initial part of the interviews. Nevertheless, the pattern of objective answers for some questions, such as the public authorities’ actions, the neighborhood association’s participation, and local transportation, matched the respondents’ perception from the initial part of the interviews. Transportation, in particular, is a highly evaluated element in Botafogo, in addition to the bohemian character of the neighborhood, which should also be stressed. Moreover, some respondents’ lack of knowledge about the neighborhood association’s participation is noteworthy, with two respondents choosing not to answer the question.

Regarding the residents’ complaints, it is noteworthy that when answering this item, some tried to emphasize that the complaints are made by specific residents and do not reflect the majority’s view. This may explain the low scores assigned to this issue (1 and 2), despite the existence of official records showing a recurrence and increase of complaints in the neighborhood, as public knowledge. For other issues, it was impossible to trace a pattern of perception among the respondents since many of the ‘objective’ questions were not addressed in the block of semi-structured questions from which the statements were collected and analyzed thematically. The following table presents the results of the answers, with the mode and mean calculated.

4.2 Santa Tereza

Santa Tereza is a neighborhood located in the east region of Belo Horizonte. It received this name in 1928, thirty-one years after the foundation of the city (1897). Santa Tereza was initially occupied by Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese immigrants (Neves, 2010). It currently has about 16,000 residents, ranging from long-time families settled in the area and new residents, especially students and artists. Most of these residents are middle-class, but there are also lower-middle-class residents in the Dias and São Vicente villages and the Matias and de Souza quilombos.

As the birthplace of many cultural manifestations such as coco, capoeira, parties and festivities linked to Catholicism, open concerts in squares (samba, funk, and Brazilian country music), carnival parades, the neighborhood is known for its music, live shows, and, most importantly, for having been the place where members of prominent musical groups in the national and international scene, such as Clube da Esquina, Sepultura, and Skank, lived and started their careers.

In addition, the neighborhood is also home to the Escola Livre de Cinema, the Cine Santa Tereza, two art galleries, and an arts and crafts fair and organic produce market. It also shelters almost twenty Carnaval street party blocks, several bars and restaurants. According to reports from some respondents, there are 80 bars on the 63 streets of Santa Tereza. The neighborhood has four squares, the Duque de Caxias Square being the most important for its size and fruition, and two hospitals. It also has three health centers and seven schools, including the Tiradentes School of the Military Police of Minas Gerais and the District Market of Santa Tereza, as well as local businesses.

The neighborhood is located near the city center micro-region of Belo Horizonte, combining several architectural styles while maintaining the typical attributes of a country town. In 1996, Santa Tereza became a Designated Area (ADE) in the city’s master plan. According to the newspaper Sta Tereza Tem, the historical-cultural characteristics and the need to preserve the residential landscape led the city to limit the maximum height of buildings to 15 meters (low height, with about three floors) and the maximum area for the installation of certain activities to 400 m2, such as schools. Impacting activities such as industries or large developments are also prohibited.

Unlike most neighborhoods in Belo Horizonte, its topography is flatter. The streets are narrow, and so are the sidewalks, which have several swells. Two bus lines serve the neighborhood, and there is a subway station. The region is not particularly forested, but the Coletivo Arboriza BH (Afforest Group BH)was born in Santa Tereza when residents realized, in 2018, that the neighborhood had eight residents for every tree planted. From this realization, the collective started to plant seedlings, and this activity became so relaxed as to inspire the creation of a carnival block parade.

The following photos aim to identify some aspects of the neighborhood, such as urban shapes and their uses and conflicts related to the creative economy. As mentioned, the Duque de Caxias square is the neighborhood’s main square, with a green area and appropriate space for children, the home of fairs, and artistic and musical performances. The main church of the neighborhood, the Santa Teresa and Santa Terezinha Parish, is located around this square, as well as the Cine Santa Tereza and the Tiradentes School of the Military Police of Minas Gerais.

Caption: (a) Duque de Caxias Square; (b) Duque de Caxias Square; (c) Cine Santa Tereza; (d) Santa Teresa and Santa Teresinha Parish; (e) View of Rua Mármore; (f) View of Rua Mármore; (g) View of Rua Dores do Indaiá; (h) View of the intersection of Dores do Indaiá and Conselheiro Rocha streets; i) View from Rua Conselheiro Rocha; j) View from the intersection of Paraisópolis and Divinópolis streets; k) Tribute to Clube da Equina (Paraisópolis and Divinópolis streets intersection); and, l) Casa Circo Gamarra space in Vila Dias.

The photos of Ruas Mármore, Dores do Indaiá, Conselheiro Rocha, Silvianópolis, and Divinópolis aim to show the different architectural styles of the neighborhood, thus highlighting the preservation of the residential landscape and the characteristics usually associated with small towns in the interior of the country. However, the neighborhood’s urban shape has changed, and the occupation of public space by parklets has increased recently.

Finally, the last two photos show the intersection of Paraisópolis and Divinópolis streets and the plaque in honor of the Clube da Esquina installed in this space. It was on this corner that young residents of the neighborhood would gather in the late 1960s to compose and play their instruments, starting their musical careers.

The Neighborhood Association was established in the 1980s, but it was in the second half of the 1990s that it became more active. The intention of a construction company to build the largest building in Latin America in the neighborhood motivated a community movement called “Save Santa Tereza.” It was pressure from this movement that led to the reversal of the project and laid the foundations for transforming the area into a Designated Area (ADE) in the city’s master plan in 1997.

The Association has recently acted to use the District Market more efficiently, with a project that became the primary guideline for the Public-Private Partnership aimed to readjust the site, with assured occupation by local entrepreneurs focused on arts and crafts, gastronomy and cultural productions, community garden, family farming, and organic products.

The Santa Tereza neighborhood community is very active, to the point of having a women’s group with more than 200 members, the Coletivo Arboriza BH (Afforest Group BH), and the Rede de Lixo Zero, with 120 members, which transforms organic waste from the homes of its members into fertilizer, meeting the demand of both residents and organic producers. All these movements collaborate with the Neighboord Association.

The public authorities’ actions in Santa Tereza follow those in force in other neighborhoods of the capital, with no distinction for such a present association. For the Association’s representative, the main local problems are noise pollution from bars, the occupation of public spaces in the neighborhood in the form of parklets, and heavy traffic on narrow streets at an inappropriate speed. Regarding the first issue, the Association, responding to the request of the residents, managed to establish an operating time limit for shows held in establishments based in the neighborhood.

In the interviews with eleven entrepreneurs/producers, several consensuses could be observed. The establishments are small, where only one to 30 people work. The choice of Santa Tereza to host these business activities stems from the fact that some of the eleven respondents have lived in this neighborhood for a long time. The ones not residing there have chosen Santa Tereza for being a welcoming, residential neighborhood that resembles a country town and, most notably, for its cultural dynamism. While most of these respondents are not associated with artistic and cultural activities developed in the neighborhood, they do highlight the fact that Santa Tereza is booming, effervescent milieu, due to the various activities developed in the area, especially musical ones, and for having been the cradle of important artistic movements and groups. However, some think this effervescence has gone too far, attracting residents from other neighborhoods and tourists who often do not respect the local customs.

Some of these residents participate or have participated in the Association and understand that the institution represents the community’s demands. On the other hand, bar owners do not participate, probably due to the limitations imposed on the time and place of their business activities. As for the relationship with the public power, they see it as neither regular nor exceptional. The residents complain about the traffic, the lack of buses serving the neighborhood, the cleanliness of the streets, and the garbage collection service.

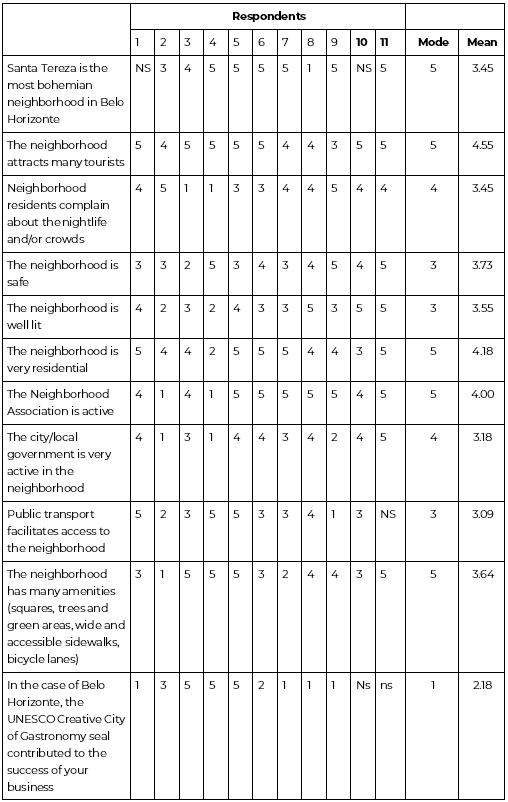

Table 4 below illustrates the perception of the eleven respondents concerning the statements made about Santa Tereza. On a scale of 1 to 5, they expressed their opinion between strongly disagree (1) and strongly agree (5).

A higher incidence of “totally agree” answers for the statements can be seen: the neighborhood attracts many tourists; the neighborhood is very residential; the association is active. In this case, the mode was 5, and the mean was above 4.

While more than half of the respondents totally agree with the statement “Santa Tereza is the most bohemian neighborhood of Belo Horizonte,” some of them disagreed for not wanting to associate this attribute to the place; they see the bohemian lifestyle as a form of vagrancy and do not want this for the neighborhood, or because they do not know if Santa Tereza is indeed the most bohemian. Another statement with a high mode was “The neighborhood has many amenities (squares, trees and green areas, wide and accessible sidewalks, bicycle lanes)”; however, its mean was below 4.

Finally, “In the case of Belo Horizonte, the UNESCO Creative City of Gastronomy seal contributed to the success of your business” was the statement with the highest level of disagreement, as few respondents were aware about the UNESCO seal, and some have businesses not related to gastronomy. Those who totally agreed are restaurant owners and are part of the city’s gourmet circuit, participating in several gastronomic festivals. With the except for this last case, these answers are evidence of the low capillarity of public policy regarding the neighborhood’s cultural scene.

5. Concluding notes

Botafogo, in Rio de Janeiro, and Santa Tereza, in the city of Belo Horizonte, are neighborhoods that stand out in the creative ecosystem of their cities. Despite being neighborhoods with very different socioeconomic profiles and urban outlines, both have developed cultural quarters that attract new producers, local consumers and tourists in search of cultural enjoyment in bars and restaurants, live music venues and street events, such as gastronomic and arts and crafts street fairs, and carnival street parties.

This article aimed at analyzing how social, economic, cultural, institutional, and urban attributes have conditioned the development of the creative economy in these neighborhoods, forming districts marked by clusters of companies and creative workers. Following the literature on the development of cultural and creative clusters and on the relevance of cultural quarters in urban planning and based on primary data collected via semi-structured interviews with entrepreneurs and government representatives, the research identified similarities and differences in the evolution of the cultural quarters of each neighborhood.

First, the cultural quarters of both neighborhoods developed spontaneously, that is, the public authorities did not induce this process. As mentioned, the neighborhoods have very different socioeconomic profiles and urban outlines, and this contributes to the different ways in which their clusters developed.

Botafogo is well integrated into the transport network of the city of Rio de Janeiro, with a privileged location between the city center and the South Zone (the most expensive area in the city). In the past, when Rio de Janeiro was the capital of Brazil, Botafogo housed several embassies in mansions that have been repurposed over time. Hence, with headquarters for companies, large schools and hospitals, it began to attract cultural and creative activities for people who circulate and live in the area, progressively establishing itself as one of the most dynamic places in terms of cultural and creative consumption. In this sense, we understand that the trajectory of Botafogo can be defined as “ongoing change and mutation”, according to Martin's proposal (2010).

As for Santa Tereza, an analysis of its trajectory shows that the neighborhood is a case of “resurgence or rejuvenation” (Martin 2010). A hub for cultural activities in the 1960s and 1970s, especially for music, Santa Tereza experienced a decline in the 1990s. Its residents united and fought to have the neighborhood achieve privileged status in the city’s master plan, safeguarding its layout and material heritage. Santa Tereza is now the locus of the city's gourmet circuit, offering several other cultural activities and attracting tourists and residents from other neighborhoods.

Because they are related to on-site cultural fruition, cultural and creative activities in the aforementioned cities condition the development of cultural quarters marked by local connections, as defined in Stachowiak (2020). In addition, not much interaction is found between the firms, nor with the public authorities, showing that the cluster stems more from a co-location strategy than from co-production strategy, as noted in Vicente (2018). Faced with co-location, the relationship with the public authorities occurs due to problems related to bureaucracy and urban planning. It is at these times that the firms located in the cultural quarters under analysis interact most.

When we analyze the three characteristics of cultural quarters, according to Montgomery (2003), we find that all three are present in Botafogo and Santa Tereza, but with differences. In Botafogo, the diversity of activities and urban shapes highlight the vibrancy of its cultural quarters, while in Santa Tereza, it is the sense of belonging and the historical importance of the neighborhood that stand out.

Finally, in both cases, some conflicts between residents and entrepreneurs and the weakness of a governance structure are threats to the sustainability of the cultural quarters. Regarding urban planning, both cases show the absence of effective planning, even considering their different trajectories. We believe that the construction of integrated urban planning depends on a sense of citizenship that contributes to a process of socio-spatial integration. Citizenship is linked to the construction of greater solidarity among the various agents involved, as well as to the construction of mechanisms and instruments of cooperation.

In Santa Tereza, the participation of residents in the neighborhood association and its work with residents and public agencies consolidates the solidarity and cooperation necessary to well-being in the neighborhood. The tacit agreements and the social movements that exist there (containment of real estate speculation, waste collection, afforestation, noise pollution, among others) derive much more from the protagonism of the residents' network than from municipal public policy. Certainly, learning from participatory budgeting in the city since the 1990s has contributed to this activism. However, today it is the result of the initiative and organization of the residents of the neighborhood. Therefore, one can think of a bottom-up movement of urban planning not institutionalized by the municipality, but by this network.

In the case of Botafogo, there is not such an intense integration of residents as in the neighborhood of Santa Tereza due to its population scale, the presence of institutions and companies that remove from the neighborhood a strictly residential aspect and its locational situation as a place of connection between important regions of Rio de Janeiro. The residents' association seeks to act in a way that highlights the relevance of preserving residential aspects of the neighborhood, such as the creation and maintenance of squares and the need to control certain commercial activities that lead to noise pollution and irregular occupation of sidewalks. However, due to the economic relevance of these commercial activities in the generation of employment and tax collection, generally, the initiatives carried out there respond much more to the orientation of municipal policy, which seems to privilege the consolidation of Botafogo as a good environment for new commercial enterprises than to the strategy of its residents.

In future studies, we hope to expand this research to other neighborhoods in Brazilian cities, as Salvador, Recife, Fortaleza, Belém e Porto Alegre and others where there are vibrant creative and cultural scenes, in order to contribute to urban planning and to the development of the creative economy. We believe that new analysis can be complementary, especially research on the behavior of consumers who attend these cultural quarters.