Introduction

In general, a house is considered to be an object that provides protection and shelter (Balmer and Belmet, 2015). In line with this, the house is also the place where life happens and is reproduced. This implicates whoever lives there, if there are children, if its inhabitants are young, middle-aged, or older adults. Housing is also linked to the surrounding habitat, the space where homes are located, and in which both the physical and emotional environments are extremely relevant for the development of life. Feeling like you belong to an environment is not something trivial, but rather a central aspect within the possibilities of nurturing a life lived in dignity (Márquez, 2013; Escobar, 2016; Haraway, 2016; Merklen, 2023). On the other hand, the importance of the collective is essential in the production of a habitat for people who live in a particular place, as part of a network of relationships (Stavrides and Travlou, 2022; Lefebvre, 1978; Jacobs, 1993).

In the capitalist system, property is considered a fundamental right. In many western constitutions it is explicitly referenced and comes from long debates that took place during the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries (Locke, 2003; Marx and Engels, 2004; Proudhon, 1890, among other authors who have worked on this topic). From a legal perspective, many struggles for housing are pervaded by this legal and conceptual framework that protects private property even more than the right to build a life chosen by people.

The following analysis focuses on Uruguay, the country where I live and engage in my academic career ‒ in particular, the place where I do fieldwork for my PhD in Anthropology: the northeast of Montevideo. I will seek to reflect on the categories of owners and users and the way in which these categories influence (or not) the livelihoods in this territory. As in many other countries, in Uruguay, private property is considered a fundamental right by the Constitution.

The paper presents a perspective on value (Graeber, 2001), where we will question what is important for people when they inhabit a territory, as well as the need to organise to achieve basic goals, as we attempt to ascertain the importance (or not) of legal ownership of homes. The significance of individual private property is linked to a framework of valuation that is supported by public policy, and that permeates all the actions of society, but one that is not equally shared among all the population. The article presents an overview of private property in Uruguay, focusing on its foundational developments in the country. Subsequently, it opens a discussion on housing cooperatives, specifically the model that, in one of its modalities, allows the ‘user’ to be a legal person, as decreed by Law in Uruguay in 1968. Next, the paper focuses on informal settlements, in which people are also ‘users’, discussing the (un)importance of private property for people living there. Finally, some examples are shown attempting to give the reader an insight into the territory, illustrating that the contribution of this article revolves around the concept of housing for users as a social, pragmatic attribute.

The material I use in this paper comes from secondary sources as well as fieldwork I have been doing as part of my work in Punta de Rieles and Villa García. They are two working-class neighbourhoods, which characteristically have rural and urban areas, comprising 18 informal settlements, and 12 housing cooperatives, many of which satisfy the legal definition of user. Both neighbourhoods have increased in population over the last three decades, mainly due to the occupation of land and the building of informal settlements, and also the provision of housing through public policy. As part of my fieldwork, I have carried out two group interviews with people who live in housing cooperatives in Punta de Rieles, as well as five individual and two group interviews with inhabitants of the Nuevo España informal settlement, also located in Punta de Rieles. This data has served as input for this article, while the paper was also informed by data collected in previous studies on housing cooperatives (Abbadie et al. 2022, 2018, 2015).

A mix of factors: value as a way of understanding life

This study presumes that the norms and standards of valuation are rooted in the cultural systems of people (Graeber, 2001). For this reason, being able to understand from a historical-temporal perspective how they are constructed is important. If we do not consider the historical angle, it is difficult to understand the systems of valuation and also how relationships and power are built up in diverse ways (racial, gender, economic and from place of origin). People assign value to very different things according to sociocultural frameworks that pre-exist for each individual. What is valuable to one depends on the needs, understanding them as a multiple-factor construction. To understand why people struggle or make a particular choice, we have to delve into a complex system of appraisement and value (Graeber, 2001), of symbols and signification (Geertz, 2003); that allow us to understand that structures of values and meanings are socio-culturally constructed and that they permeate the way in which people understand the world.

What is valuable to people? Is having a house with legal papers valuable? Is the legal aspect an important one to ensure we have dignified and enjoyable lives? Is ensuring there is food and shelter, and no risk of being removed from a house they built with effort and love valuable? All those questions are extremely important for people who live in lower-income neighbourhoods in the northeast of Montevideo, which have not been legally regularised, such as the ones in Punta de Rieles or Villa García.

According to the National Institute of Statistics (INE), housing is ‘any separate and independent enclosure, built or adapted for the shelter of people. They are classified as individual or collective, taking into account the type of household that occupies them’ (Continuous Household Survey, INE, 2022a - own translation).

However, this definition is limited if we associate it with a perspective of access to fundamental rights, in which inhabitants can develop a dignified life. A richer perspective is one where, in addition to life satisfaction, the process of access and adaptation to life is taken into account. This is related to being able to understand housing, not as a finished product, but as a participatory, concerted and evolutionary management process, which is able to generally satisfy the needs of daily life and requires adaptation to the needs and possibilities of its inhabitants (Delgado, 2014, p. 130).

This definition of housing is combined with Jorge Di Paula’s definition of habitat, understanding that it transcends the individual and includes a collective, social dimension, which implies the satisfaction of physical and social needs linked to our daily lives: ‘It transcends living under one’s own roof and the traditional services of water, sanitation, etc., to include socio-cultural, socio-economic and socio-political needs’ (Di Paula, 2006, p. 2 - own translation). Thus, understanding that one’s habitat is part of something ‘productive, economic, social, environmental and historical-cultural; that interacts with its surrounding environment (the neighbourhood) and with the city, and that establishes a network of relationships with other territories and with other human beings’ (Delgado, 2014, pp. 129 - own translation). Merklen (2023) also has elaborated upon this concept, focusing on the idea that a home and housing are not the same thing, and that the concept of home means a place of social relations.

‘... a conception of the house is proposed based on its insertion in a web of social relations of three different types: those of the family, those of the neighbourhood and those of society, the latter being present through the infrastructure of urban services (…) the relationship between the private, the intimate and the social are discussed, including as the territory of neighbourhood activism.’ (Merklen, 2023, p.1)

This concept should be explored more deeply to understand the mechanisms that are vital for fostering ‘lives that deserve to be lived’ (Fernández Alvarez & Perelman, 2020; Narotzky & Besnier, 2014) as we think of the home as a network of relationships (Merklen, 2023). The physical structure of the house is only one part of the home. The environment is yet another construction, one that is an essential part of the symbolic and material possibilities of social interaction, an ongoing process. Focusing on the process implies understanding issues such as having the services that those who live there need, an environment in which residents feel comfortable, and a place where they can feel safe. These aspects do not depend on whether there are assets involved or not but are related to considerations such as being part of a place, finding that the services available are adequate, or feeling comfortable with the neighbours, among many other variables that matter in daily life. A property becomes important if one bets on the possibility of modifying, renting or selling the property, adapting it to their preferences, treating it not only as a space of use but also as a capital asset. Such flexibility ensures that property serves both as a place of residence and as a means to navigate social and economic mobility1. But, according to the data collected in the course of my fieldwork, a sense of belonging is a mechanism that is acquired over time, with use, and with the relationships and emotions that are manifested in a place.

The daily relationships of proximity that take place are important in this process. A neighbourhood is not homogeneous, but on the contrary, it contains a heterogeneity that is based on territorial relationships of proximity. We have called this territorialidades barriales, or neighbourhood territorialities (Abbadie et al, 2019). Feeling part of a neighbourhood territoriality fosters a participatory process to be implemented and helps to reinforce a sense of belonging. Feeling part of an environment is not something trivial, but a central aspect within the possibilities of attaining a life lived with dignity.

Action to reach goals

Individual goals are regulated by norms in each society. Different actors play different roles in the process of providing housing (Balmer and Belmet, 2015), including the entire legal framework. This also produces different reactions in people, in finding a balance between what is desired and what can be accomplished. Alvarez Rivadulla (2017) in a study on informal settlements in Montevideo, and Holston (2008), who focuses on the favelas in São Paulo, Brazil, identify the relation between urbanisation and democratisation as a combination that leads to ‘insurgent citizenships’ on the peripheries of Latin America. These scholars argue that it is through life’s daily struggles that poor people in peripheral countries come up with ways to face their problems and fight for their right to belong to urban spaces.

The need to develop life sustains these insurgent citizenships mentioned by Holston and Alvarez Rivadulla. The way in which people in many of these informal settlements organise themselves to get access to water, electricity, public transportation service, to health care, is much greater than the average citizen’s participation process to get the same basic services. Sometimes it is accomplished with the help of NGOs, but most often just through self-organisation and struggle. Trudging up and down the halls of public state agencies, making time for meetings and writing notes for public files, which can take hours, is part of the efforts these people need to make. These actions are part of a collective effort. The relationships that are built galvanise or restrict these interactions and make them fruitful or in vain. All the more, when a community has to organise to satisfy its needs, relationships such as these are essential to a successful outcome. The relationships that are forged between people, or groups of people in a close proximity to each other, either enable us to live or hinder us.

Some traits of these insurgent citizenships can also be traced to the first experiences of housing cooperatives and even to the first steps that cooperatives must take to legalise their existence ‒ that of doing the paperwork to obtain legal status for the cooperative. Finding land to build on, holding solidarity workdays with other cooperatives, selling to raise funds, are only some examples of the activities these collectives usually get involved in-. At some point these collectives feel the need to organise themselves, to resist the norm, the status quo, and to obtain similar conditions to the rest of society.

In the words of Stavrides and Travlou we can also say that: ‘Commoning practices encourage creative encounters and negotiations through which forms of sharing are organized, and common life takes shape. They do not simply produce or distribute goods but essentially create new forms of life (Agamben 2000), forms of life in common…’ (Stavrides and Travlou, 2022, p.1).

This ‘life in common’ is not always simple and pacific but can be complex and rather tense. It depends on the capacity of the people involved and whether the goals are reached. Once the objectives are achieved, how social relationships are managed and developed defines if what has been achieved can be maintained. Housing as commons is an interesting political project, but sometimes aspects related to power and control over the territories, can destroy or at least hamper socially valuable processes.

According to Denis Merklen (2023), it is the combination of poverty and absence of public institutions that pushes the creation of ‘community’ organisations that find their focus, like any community, in the family and the home. For this author, in Latin America, private and public life are intrinsically interwoven within the neighbourhood and the interpersonal and informal relationships that constitute them.

These organisations are not discretionary, they are necessary to survive, as part of an ethos of cultural, reproductive and political survival (Appadurai, 2022), and not because they are motivated by the ideal of ‘participation’, but rather because the institutions of the social State fail (Merklen, 2023). Most of the people who live in informal settlements or housing cooperatives are not ‘baby capitalists’, who live on small-scale properties, they are people who struggle to survive in an unequal urban system.

An overview of private property in Uruguay: A development framework in the constitution of the normative? A historical perspective

The discussion between users and owners implies we recognise the importance of private property in Uruguayan legal regulations. We can differentiate between individual private property ownership, collective private property ownership, and the absence of property ownership. This classification will allow us to focus on two different ways of not owning personal private property: user housing cooperatives, where there is collective private property ownership, but it is not individual; and informal settlements, where there is no property ownership at all2. Both models are different. In the case of cooperatives, residents cannot be evicted, and in fact they can pass on their social assets to their heirs. In the case of informal settlements, there is no legal framework that protects someone who is not the owner of the land. This is important because property is key to legal tenure, and without ownership, access to housing is not guaranteed to last over time. However, the experience of users of housing cooperatives is interesting to link the possibility of making a social movement where the focus is on the use of housing and not on its exchange value.

Individual private property has been the priority model adopted in Uruguay for building, including public housing. It has been the preferred kind of construction in Uruguay since the country’s founding in the 19th century.

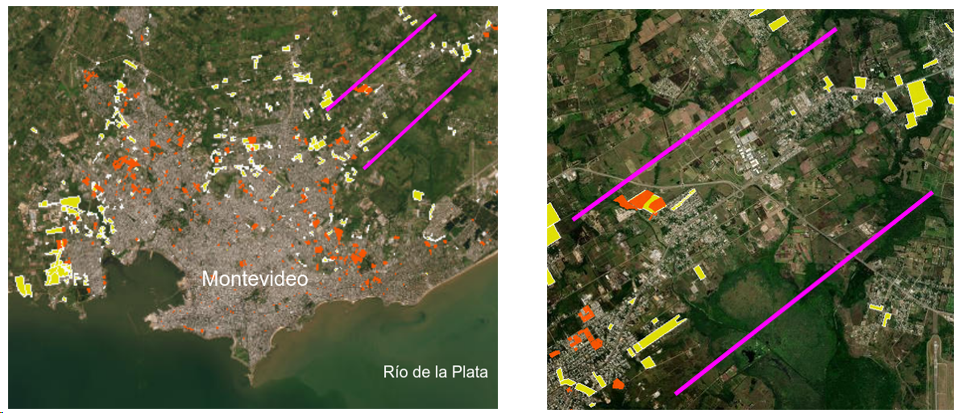

Own elaboration, based on a map taken from the Territorial Information System, DINOT, MVOT(2023)

Figure 1 Map of Montevideo city

Montevideo is the capital, and the central economic city of Uruguay, a southern Latin American country of 3,444,263 people, with a surface area of 176,215 km2 (INE, 2023). The country has been independent since 1830, while Montevideo has been the main city since its foundation as a fortified settlement for the Hispanic colonial empire in 1724.

The planning of the city is essential to understanding where the areas in which there is private property (owners) are located, and where there is not (users). The geographical distribution of the city is marked by the private property of land ownership. As we can observe in the map of Montevideo (Figure 1), the majority of users who live in informal settlements or housing cooperatives, are located on the periphery, corroborating a geographic pattern of inequality. In the case of informal settlements, the pattern is even more marked. This has been reproduced since colonial times, as the city has expanded, always pushing people who are not landowners to the urban periphery.

The first non-Amerindian settlers of Montevideo were Canarians, coming from the Canary Islands. They were provided with land in the urban central area that took shape between 1724 and 1730, and also with pasture or farms scattered over what was known as the Government of Montevideo. Property ownership at this stage was already a clear indicator of land appropriation. The Indigenous people who settled here, it was not theirs to possess, nor were they going to have it later. The conquerors’ regime was imposed as the axis of moral value over the following centuries. Legal tenure thus began to take precedence in the social structurisation of land and housing ownership.

The consolidation of the National State in 1830, with the emergence of the República Oriental del Uruguay, or the Eastern Republic of Uruguay, in English, would consolidate this bid for nationhood within the global capitalist system, where land ownership was a recognized fundamental right.

In the 20th century, two theoretical frameworks, one European and the other Latin American, influenced Uruguayan society, especially in terms of the urban landscape; the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM), and the conceptual ramifications of dependency theory linked to the development of the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC, or CEPAL, in Spanish), especially in its first phase (1948-1960).

During the decade of 1960s, the concept of development was a significant one for the public policy of Latin American economies (Rodriguez, 2006), especially in the Southern Cone region. This framework focused on the importance of the State in the development of infrastructures to support the strengthening of the industrial sector, the development of the Import Substitution Industrialisation model (ISI model) and, subsequently, the entire economy. This theory was developed mainly for urban areas. In most Latin American countries, the migration from rural to urban areas was substantial from the 1940s through the 1960s as a result of many factors, the main one being labour demand, due to ISI model-led industrial expansion (Bértola y Ocampo, 2010). Many of these migrants settled on the periphery and built their houses according to their ability. In Montevideo, the first signs of the existence of informal settlements date back to this time.

Both models were important in urban public policy planning, and the concept of development began to be implemented as a fundamental axis in what was understood as ‘what should be’. As a result, the urban form and expansion of the city of Montevideo were influenced by these theoretical ideas. Although in some discussions of both theories, commonality was an issue that had a place, in general, what prevailed led to the increased development of private property. One source of tension between theoretical aspects and actual reality arose between state-planned urban development, the real estate speculation that went hand-in-hand with the financialisation of the land market, and the constitution of the city that the inhabitants daily built to the best of their ability, often occupying lands that did not legally belong to them.

Housing cooperatives

In the second half of the 1960s, a movement concerned with the life conditions of the poorest inhabitants worked out an experimental model of livelihood, the housing cooperative (Terra, 2018). It was endorsed and implemented through Law no. 13.728 of 1968, constituting an alternative to the production of lower-income housing and gained ground after its promulgation (Nahoum, 2008; Machado, 2022; Abbadie et al., 2022; 2015).

The Housing Law of 1968 was a modern blueprint focusing on the needs of lower-income families. It rekindled an idea that was in the 1934 Constitution on the right to decent housing for each and every member of society and provided it with a regulatory framework. It is extremely likely that its base ideas were influenced by the CIAM, especially on basic family housing and the importance of the availability of communal spaces available, as well as by the ECLAC theory.

A characteristic of the first years in which the Housing Law was applied, was the importance and relevance of mutual aid housing cooperatives (CVAM for its acronym in Spanish), which were mainly intended for ‘users’. This meant that the cooperative was the owner of the houses they built, but the people who made up the cooperative, who lived there and who assumed responsibilities throughout the building phase were not private owners of the homes they resided in. As a result, the chance to conceive a housing project as a common good arose: housing as a common.

According to Machado (2022), in the 2011 census, 30,045 homes belonging to housing cooperatives were surveyed. In more recent data, the National Institute of Cooperatives of Uruguay (INACOOP) indicated that there were 2,197 housing cooperatives in 2024 (INACOOP, 2024). Although housing cooperatives do not exceed 3% of Uruguayan households, another INACOOP study revealed the high visibility of cooperatives for the local population, among which housing cooperatives were the ones with the most visibility of all (INACOOP, 2023). In Montevideo, several housing cooperatives are emblematic, such as the case of mesas and zonas cooperativas, made up of several housing cooperatives that came together not only to build but also to create a common space to live in (Machado, 2022).

Housing cooperatives in Uruguay are mostly founded based on the user model, or collective ownership regime. This is one of the most significant particularities of the model, because the ‘user’ regime is atypical in Uruguayan legislation, due to the hegemony of private property and the exceptionality of its collective equivalent. ‘Users’ do not acquire ownership of their house, but rather the right to simply use it, as well as the possibility of passing it onto their heirs. But this regime also implies certain limitations for residents, since the interior or exterior space cannot be modified without the consent of the cooperative, nor can the house be sold, exchanged, or rented.

While cooperatives emerged as a housing alternative for the poorest sectors of society and thus ensured them a place to live that was legally compliant, the original intention would be modified over time. It became a feasible alternative for those from the middle class who had difficulties getting mortgages to pay for housing, or who had a politically motivated desire to be part of social transformation in which the cooperative system was a viable alternative. Housing cooperatives continued to be spaces for building life for a population earning low incomes, but mostly for those working in the formal sector.

However, except in a few cases, the poorest sectors without jobs or formal incomes mostly continued to build illegally, either on land that did not belong to them, or through processes that were not legally compliant. Why did the cooperative model not spread further in lower-income sectors? Is the legal framework of little importance to certain people? Or is it that it takes a certain capacity for organisation and agency?

The political intentions behind developmental models put private property front and centre, be it through individual or collective. One way or another, the legal bureaucracy that must be followed to have formal access to land, the time it takes, or the high cost that this entails, expose a substantial number of people to a state of illegality. There are public policy practices, where a certain approach to building a city is valued over others (Roy, 2015). We believe that being able to understand the theoretical bases behind these sanctioned and non-sanctioned ways of living and building a city can enable us to understand the value and meaning of what is at stake in the expansion of Montevideo.

Informal settlements

In Uruguay, as well as in many other countries, people make their home on land that they can occupy, because it is available, because it has been enabled to them, or because it is part of an organised occupation. There is also the possibility of accessing land through the purchase of the built spaces, although not the land, by illegal sale. Many of these houses are located in what we know as informal settlements, also known as slums3. In them, people make use of the houses that they build there but do not possess any title deeds to them4.

Even though there are other ways of being users, as happens in the case of housing cooperatives, the fundamental difference is that in housing cooperatives, property ownership does exist, even if it is collective rather than individual.

According to UN-Habitat (2022), 1.6 billion people live in inadequate housing around the world, of whom one billion live in informal settlements in deprived conditions. According to Nassar and Elsayed (2018):

‘(...) Informal settlements refer to a wide range of residential areas formed by communities housed in self-constructed shelters that are perceived as informal on the basis of their legal status, their physical conditions, or both (...)’ (Nassar and Elsayed, 2018, p. 2368).

Informal settlements have the particularity of not being legally regulated and are usually settled on land that had not been planned for city development. They vary from city to city, and even in the same city there are different kinds of informal settlements, with residents from the working class to immigrants, or people who struggle to put a meal on the table every day and that live in terrible conditions. Informal settlements are spread over Latin America, symptoms of a prevailing unequal urban model. Nowadays, in Montevideo, most of the informal settlements are located in the periphery. Despite the amount of public policies launched since 2005, informal settlements have grown (PMB-MVOTMA, 2018), forming a response by the people who inhabit the city, and at the same time providing alternative readings of possibilities and value.

Di Paula and Lamoglie (1999) wrote many years ago that the main growth factor in Montevideo was the expansion of informal settlements. In the 1980s and 1990s, informal settlements spread over the periphery of Montevideo. The expansion was mainly due to interurban migration, caused by the loss of jobs in the industrial sector, in a neoliberal policy context that originated from the dictatorship from 1973-1984, and continued during the democratic governments over the 1980s and 1990s. Due to a low birth rate that began in the 1950s, irregular settlements grew during that period without population growth (Rivadulla, 2017).

The land occupations occurred mainly in the late 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s. The deindustrialization process caused the expulsion of many people from the formal housing market. People who owned a house, who had mortgages or who rented in the formal market were expelled from the formal economy once they lost their jobs. The quantity of people living in informal settlements in Montevideo rose during this period, more than in any other period (Rossal et al., 2020).

Nowadays, in Montevideo, there are 344 informal settlements according to official data from the Municipality, made up of 34,333 homes and an estimated number of 122,445 people (IM, 2023). In the city, the total population is 1,383,601 (INEb, 2022), which means that almost 8.85 % of the population of the main Uruguayan city live in an informal settlement, occupying property while not having legal deeds to it. In other words, it is not their decision whether they will stay there or not. The reasons why people stand in an informal settlement are many and varied. Many people affected by evictions have nothing to fall back on other than their own capacity to act and work and end up living in informal settlements. There is also the phenomenon of internal migration. Between 2000 and 2011 the number of farmers living in rural areas dropped from 189,838 to 106,961 (DIEA, 2011). This population decrease has an impact on the increase of population in urban areas and in many cases in informal settlements. Some of the people interviewed during my fieldwork, who live in the informal settlements of Punta de Rieles and Villa García, come from different regions of Uruguay. Even though the empirical data is scarce, most of the interviewed who live there are known to have come from departments such as Cerro Largo and Treinta y Tres, two regions connected to the northeast Metropolitan Region by route 8, one of the most important infrastructural axes which connects Montevideo with rural areas and other smaller cities. Some of the people interviewed came to the capital city in search of better opportunities, especially jobs in the construction sector, services and industry sectors. Some of them even keep their houses in their places of origin, and sporadically return there.

A characteristic of informal settlements in the northeast of Montevideo, is the dynamics of population flow, since populations in informal settlements are frequently on the move. Not only residents of those neighbourhoods tell us that, but also teachers at schools in Villa García and Punta de Rieles have pointed out how children change schools sometimes once or twice a year because their parents move to other parts of the country in search of work. Probably the fact of not having regular employment exacerbates this phenomenon, especially for seasonal work such as forestry, crop harvesting, working in the construction industry or tourism services. Taking such factors into consideration, not only is building a home in an informal settlement conducive to staying in one place, but also makes movement more flexible, through not having to pay expenses or rent while they are not living there, and not having to participate in assemblies or commissions during the time they are away from the neighbourhood5.

By not being the owner, the chances of being able to stay in the place you have built for yourself to lice in are far more unlikely. Even if it is true that many informal settlements are financially very poor, in many cases the built infrastructure and the social networks woven over the years, established neighbourhoods fully services, except for having legal status. In some cases, these neighbourhoods accommodate three generations of families living there. If relocation is forced upon them, then in the best scenario these families will have to leave their home and move to state-provided housing (PMB-MVOTMA, 2018). Worst, they are forced to move to another informal settlement and then start from scratch all over again, or worse still, end up homeless living on the streets6. According to statistics by the Montevideo Municipality (IM), there are more than 3000 homes waiting to be built, to account for ongoing processes of relocation (IM, 2023).

Many of the people who live in informal settlements have no choice nor the opportunity to get access to housing in any other way. Even though it is possible to be given state-recognised accommodation, complying with certain formalities is required to have access to them, as is the case of housing cooperatives. On the other hand, economic factors also come into play. According to the fieldwork data, a house built in an informal settlement can be sold informally for from USD 7,000 to USD 20,000, depending on the location and the conditions of the house itself: roof and floor materials, quantity of bedrooms, bathrooms, if it has a garden, a garage, and the safety of the neighbourhood. If the informal settlement is located in a place with legal tenure, because, for example, people have organised themselves to reclaim it, or they have bought the property deeds to the land7, the selling price of the houses is higher because there are fewer chances of being evicted. When families do not have any legal resources, and the risk of eviction is higher, the price of houses is calculated according to the quality of construction materials. This can end up being less than a quarter the monetary value of a house on the formal market.

According to a paper written by the National Housing Agency (ANV) the average price of purchase and sale transactions under the horizontal property regime in Montevideo was USD/m² 2,013 in 2021 (ANV Report, 2022). This report also analysed prices by area, finding that in the richest areas on the east coast of the city, the average price of a house was USD/m² 2,306, followed by the central zone (USD/m² 2,082), and then another central area with a middle-class population (USD/m² 1,736), and finally the periphery with an average of USD/m² 1,576, based on properties sold in the formal market. This means that, on average, a new house on the outskirts could cost USD 70,920. According to data on used properties for sale, they can be found for USD 45,000 on the formal market, which on average is at least double the price of what is available on the informal market. In many cases, these houses are in worse material conditions than the ones in the informal market but have legal status.

Beyond Siberia. Property in Punta de Rieles

Siberia is one of the streets of the Nuevo España informal settlement, which is located in the east of Punta de Rieles, near the Manga waterway. The settlement was created in 1989 through an occupation, followed by the occasional land sale. For several years, there has been a neighbourhood commission engaged in getting residential properties legalised.

One of its many successful initiatives was the petition for a public transportation line, which allows residents not to have to walk 2 kilometres to take a bus, as they had to do before. Streetlights were also installed and centrally located streets paved in 2020. The commission is made up of residents who live there and work towards improving the neighbourhood. They self-organise in a former healthcare post which is now the headquarters of the commission. During the Covid-19 pandemic, they also operated a soup kitchen for the needy. Their main project nonetheless, is to get the informal settlement legal status.

Legalisation should allow for formal ownership of the houses. This is a process whereby land users - ‘illegal residents’ - become owners of the same properties they have lived in for more than three decades. Most of these houses were built by the people living there. They have been adding rooms as their families grew, and making improvements, such as plastering, renovating ceilings and floors, or creating parking spaces for a car or a motorcycle. Nuevo España is estimated to have around 700 hundred homes. Not all houses are of the same standards, they have been built over different periods and in different parts of the neighbourhood. Nuevo España is estimated to have around 700 homes.

In Uruguay, the recourse to ‘pre-emption right’ / ‘right to buy’, is something that users of a house can apply for after 30 years of occupation, provided they took good care and lived there consistently during that period. Besides this, the government can regularise ownership through the Neighbourhood Improvement Programme (in Spanish, acronym PMB8), if the zone is marked as a priority area for the programme. Nueva España was subject to a previous attempt at legalisation that ended in failure in 2002 when the process came to a halt. Since 2018 the Neighbourhood Commission has been trying to gather information on the best ways to embark on a new legalisation process.

As for the opinion of Nuevo España residents on the decision to seek legal status for the neighbourhood, they have contrasting opinions. Some want to see it through, and as a result, be able to own their homes. Being homeowners enables them to ensure the future of their houses, as they cannot be expelled or evicted without compensation, neither by private interests nor the State. Without legal ownership of their property, they feel unsafe, and some of them express that:

Without the legal property of the houses, they feel unsafe, and some express that:

‘Having the right to our homes, we feel calmer. Here it’s up in the air, it could be, or not.’ (An interviewee in 2022 - own translation).

But there is no agreed consensus on this, some inhabitants of the settlement not wishing to commit, or in other words, take the steps required to be able to have legal tenure over their houses, not being interested in becoming owners:

‘Some don’t. They don’t want to know. These people don’t like to pay for things, they are comfortable are they are. What’s more, they sell their houses cheaply and go elsewhere. People were happy with the streetlights and all that, but when they have to pay taxes, they’ll just leave.’ (An interview in 2022-own translation).

One of the main reasons for these tensions is that when legalising houses, or in other words becoming property owners, there are obligations that must be met, especially regarding the payment of taxes. Aside from that, regularisation means registering who lives where which can also complicate matters for some of those who make their home nowadays in informal communities and do not wish to be identified. They are also places where the informal economy develops. Whenever regularisation processes occur, many of the families who live in the informal settlement decide to move on to another, even if they have to build a new house and start all over again.

The distinction between owners and users is not a new one. It is interesting to learn how in some middle-class sectors they have been able to gain access to urban land through its occupation. An example of this is the initial formation of the urban centre of Punta de Rieles. In a memory recovery workshop, some neighbours remembered cases of occupation and subsequent legal regularisation in the central part of Punta de Rieles. They told the story of a well-known family from the neighbourhood, that occupied land for several years. When the oldest members of the family died, a couple of decades ago, their descendants found out they were not the proprietaries, and carried out procedures for the possessory rights, which took time and money, but today those properties are legally theirs. It is an interesting exercise to compare and contrast the different experiences involved in occupying these territories, keeping in mind that some of the inhabitants of formally-recognised neighbourhoods were originally illegitimate occupants of the land on which they were built, and over time and with recourse to the legal system, they managed to achieve formal occupation rights.

Legal tenure is something important to ensure permanence but is not essential in the short term. In some cases, it is also something that can force out inhabitants who do not wish to legalise their situation or create tensions within a neighbourhood organisation.

Some final reflections to conclude

Being an owner or user does not simply guarantee access to a house of one’s own, nor better conditions for families who live there. It is a complex, multifactorial dynamic that motivates someone to get the most out of life. It is also connected with the possibility of building an enjoyable environment to live in, a territory where a person can feel at ease. The social networks that are constructed are essential parts of this.

Access to decent housing in a desirable setting does not always coincide with the possibility of legally owning one’s place of residence, or with living conditions that satisfy family needs (proximity to the workplace, whether family or friends live nearby, or being close to where the family has lived for decades). In the long term, this characteristic has shaped some logic that prevails in society, and whether in the experience of users, housing cooperatives, or informal settlements, internal tensions begin to flare up regarding the importance of legal tenancy.

On the other hand, access to property has been one of the most important rights within the legal framework of Uruguay, especially on the matter of land tenure. The cooperative model that emerged in the 1960s attempted to come up with alternatives through regimes of land usage, although maintaining private property at a collective level, while an enormous majority of the population in lower-income sectors continued to build informally, in spaces they occupied.

In Uruguay, in some cases, informal settlements are extremely precarious, but in others, their conditions are the same as any other working-class neighbourhood. It should not be thought that all people living in an informal settlement suffer from precarious housing conditions. In many cases, such conditions have to do with multiple factors that could be economic or social in nature. In some others, material conditions in informal neighbourhoods are as good, or even better than places where the right to live there is formally recognised, but the standard of living is poor, such as on the outskirts of neighbourhoods, for example.

It is important to note that not all settlements within Montevideo share similar characteristics, nor are they similar within the same communities. The infrastructural organisation within these informal neighbourhoods is crucial, and it provides access to essential services such as water, electric power, transport, or even healthcare. People in these places have to mobilise, not always because they want to, but sometimes it is the only way to get the basic services they need. Sometimes, these challenges strengthen social networks, creating local leaders and better living environments; in other cases, they lead to power disputes.

The role of the State is important. The State, as well as the market, along with the people who live in these informal settlements, build various relationships, that can sometimes be good and other times tense. In any case, it is essential to understand what matters to people, which is something that public policy does not always do. In some cases, legal tenure is important because it assures the right to stay in a home built over the years; in other cases, legal tenure forces people to pay taxes that families do not have the finances for, or to get involved in complex legal manoeuvring to avoid their payment, or to even declare a fixed address, which implies being easily located.

The right to reside in a house built with love and care, and in which someone has grown up and raised children their entire life, as a place of life and of creating life, should be readily acknowledged. Even if some kind of ‘pre-emption right’ does exist, the time and effort it takes to put into action are just as important. To be an owner, the only real, effective access to legal tenure depends on having the title deed.

Added to this is the question of how legal tenure affects the construction of commoning practices. To what extent can this construction be affected by differing values within the groups that lead the struggles for a better standard of living? And even more importantly, how does the struggle itself operate among people who seek a better way of life?

In informal settlements and housing cooperatives, as well as in many other places in which people organise themselves and become mobilised, housing as commons is a need that enables the possibility of feeling one belongs to the city in which one lives. It goes beyond property ownership or legal tenure but is related to the struggle to live a life of dignity.