Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ensuring access to safe, affordable, high-quality sexual and reproductive health services and information is a right and is part of the well-being of all people.1 The term transgender (TG) refers to people whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. 2 This concept is an umbrella term that encircles a broad range of individuals with varying identities, gender expressions, experiences, and needs. 3 It includes individuals who identify as male or female as well as those who position their gender identity as non-binary. 4

In the FRA 2019 LGBTI survey, in which 20,933 TG people participated, 28% self-identified as transgender women (TGF), 21% as transgender men (TGM), and 51% as non-binary. 5 According to data published in June 2022, over 1,6 million adults (ages 18 and older) and youth (ages 13 to 17) identify as TG in the United States of America, of which 0.6% were ages 13 and older. Of the 1,3 million adults who identify as TG, 38.5% are TGF, 35.9% are TGM, and 25.6% are gender nonconforming. 6

In June 2021, the European Parliament called for inclusive sexual and reproductive health (SRH) rights and sex education to make trans-specific healthcare accessible and reimbursed across the European Union (EU), reaffirmed its call to ban non-medically necessary surgeries and treatment on intersex infants and children, and called for banning sterilization requirements across the EU. 6 Even though Portugal had already established a model of intervention to be implemented by healthcare providers in matters related to gender identity and sexual characteristics of persons in 2018, no national guidelines or recommendations have been issued. Providers are expected to follow the Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, version 7, of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. 7

In Portugal, as in many other European countries, medical doctors, nurses, and other healthcare providers may conclude their formative curricula without ever contacting resources related to LGBTQIA+ issues and without receiving even basic training on that matter. 8 The lack of specific knowledge, coupled with social bias, constitutes a major factor in the reproduction of compulsory cis-heteronormativity, invisibility, and, ultimately, discrimination. 8

Aim of the study

This systematic review aimed to approach sexual and reproductive health regarding TG populations. Data from peer-reviewed scientific literature was reviewed to define the leges artis of TG people’s sexual health, which includes aspects such as contraception, family planning, and reproductive health as a whole.

Methods

Search strategy

This review was performed in keeping with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 9 The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022371962).

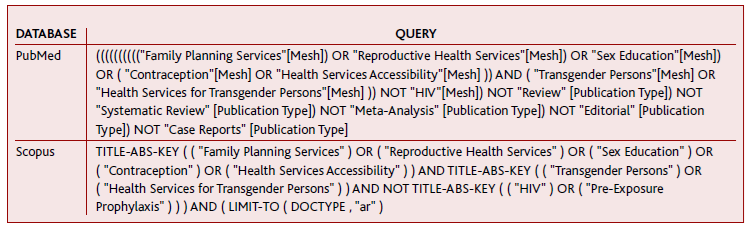

Two different databases, MEDLINE and Scopus, as specified in Table 1, were explored. Search terms were refined and adapted to each database. The search included publications published before the 24th of March of 2023, and no time or language restrictions were imposed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in this systematic review, original studies had to assess sexual and reproductive health interventions in TG populations. There were no limits imposed on the gender, age, or race of the population included. When considering health interventions, papers must have included well-defined sexual health interventions on a primary care basis (such as contraception, family planning, and sex education as a whole).

Case reports, reviews, meta-analyses, and editorial letters were excluded. Publications that did not substantively relate to the purpose of the current review were excluded.

The authors decided to exclude the topic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection from the review due to the great amount of literature on the topic and pre-existing systematic reviews with meta-analysis.

Study selection

In the screening and inclusion round, two independent authors examined each title/abstract and full text (respectively), and disagreements between reviewers were resolved by referral to a third reviewer.

Data was extracted by authors using a predesigned data extraction form. At each step of data extraction, any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The form included: the article name, author(s), publication date, journal of publication, study design, general subject, sample size, sexual and reproductive health interventions described, results, and limitations.

Study quality assessment

Three review authors independently assessed the quality of the papers using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist for qualitative studies and the Quality Assessment Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies adapted to fit a transversal study design. 10-11

Results

Study design

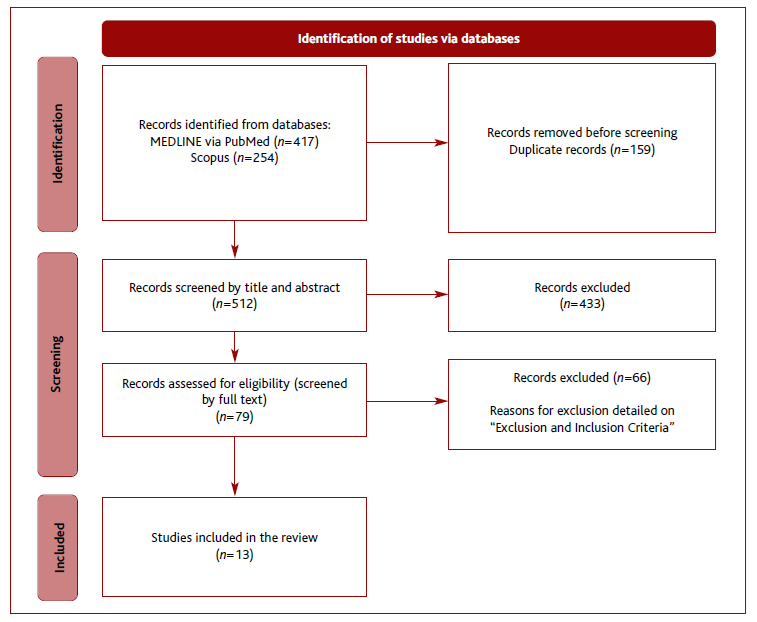

The inquiry included publications before the 24th of March of 2023, without any time or language restrictions, resulting in 671 articles retrieved. After removing duplicates, 512 studies were left for abstract analysis, of which 79 were selected. The full text of these articles was thoroughly analysed and 13 fulfilled the predefined inclusion criteria. The screening process is shown in Figure 1.

Although some studies were not included in the analysis, they provided useful information to the discussion of this paper. 12-15

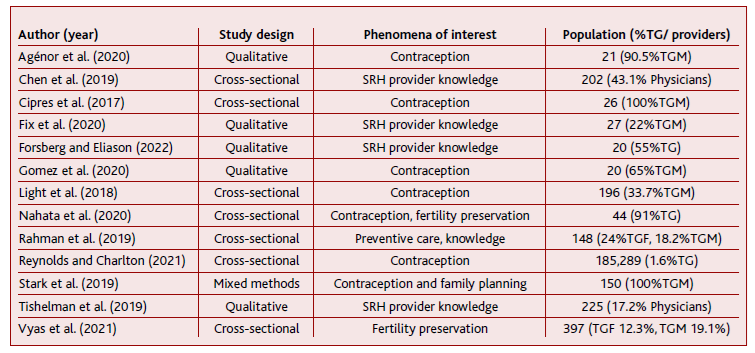

As illustrated in Table 2, six studies had a qualitative design and eight were cross-sectional. The number of patients in each study sample varied from 21 to 185,289 patients and, overall, 186,765 participants were included.

Quality assessment

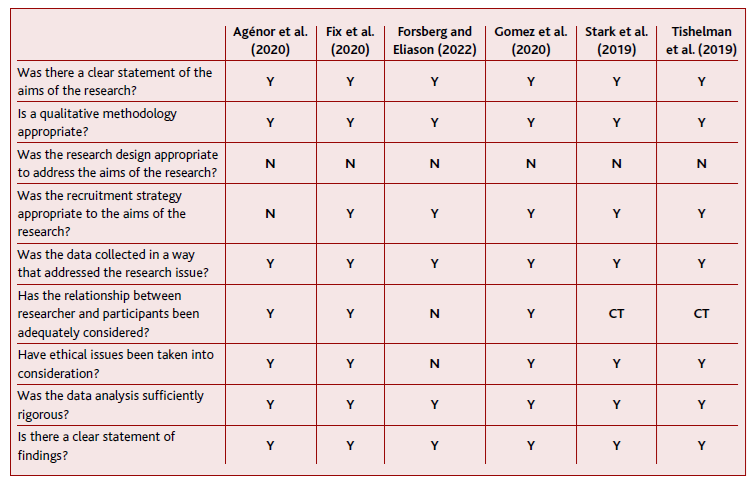

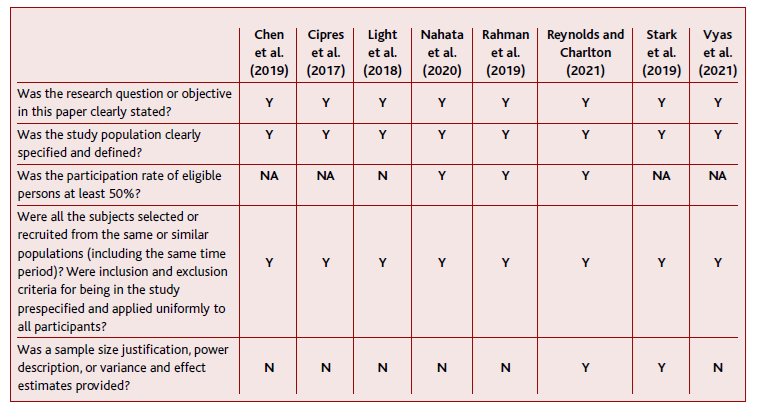

Quality assessment results are depicted in Tables 3 and 4. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist for qualitative studies and the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies were used. 10-11

Most of the studies punctuated YES (Y) on the most relevant endpoints.

Main outcomes

Patient-level issues

Contraception

Patients’ convictions and preferences regarding contraception were related to a fundamental lack of information and support regarding method choice. 16

Forsberg and colleagues stated three main reasons why TG patients do not bring up contraception at doctors’ appointments: experiences of trauma in healthcare environments or other settings, gender dysphoria, sexual fluidity, and gendered care. Additionally, the perception that most clinicians lack fundamental knowledge about SRH in the TG population directly impacts the patient’s willingness to broach this subject. 17 Ano-ther study suggested that, although half of the patients were not sure if they were offered contraceptive options from their healthcare provider, the majority (75%) were satisfied with the amount of information provided. 18

According to Cipres et al., half of the study sample were at-risk for pregnancy and desired to avoid pregnancy. Being ‘at risk’ for pregnancy was defined as having a uterus and reporting receptive vaginal sex with a cisgender man or TG woman in the prior year. Patients’ gender dysphoria, as well as the misconception that testosterone may be used as a contraceptive me-thod, impedes some TG patients from recognizing their pregnancy risk. 17,19

Despite the possibility of pregnancy, few participants reported the use of an effective contraceptive method, and many used no method, although another study revealed that most patients’ providers offered options to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and pregnancy (80%; 85%, respectively). 18

Reasons cited for preferring one contraceptive me-thod to another were the desire to prevent pregnancy, menstrual period management, and the impact of the method on their gender dysphoria. 16,20 For TGM, being pregnant may feel incongruent with their masculine gender identity or expression and could potentially increase feelings of gender dysphoria. 21

The contraceptive methods reported by participants versus the methods recommended by providers were similar. TG people chose primarily the condom as a method of contraception, followed by the pill and IUD. 16,22-23 Gender minorities have lower odds of using any contraceptive method, but have higher odds of using long-acting reversible contraception (implants, intrauterine devices). Specifically, TGM students had higher odds of using sterilization and other contraceptive methods such as the male condom, the diaphragm, and fertility awareness-based methods. 21

Even though most of the TG population uses contraception, some characteristics, such as being a student, having socially affirmed one’s gender, and having a partner, are linked to a diminished current contraceptive use. 20,23 On the other hand, a greater number of sex partners is linked to an increased current contraceptive use. Beyond contraception use, social support decreased the odds of lifetime pregnancy. 20

Many individuals expressed concern about using hormonal contraceptives out of fear of possible interactions between oestrogen and testosterone, and potential unwanted feminizing effects. 16-17,20,22

One of the most frequently raised questions by study participants was if testosterone can be used as contraception. 20 Patients desired better data on the impact of testosterone on fertility and SRH, specifically on dosage, length of treatment, and pregnancy potential after cessation of testosterone. 22

Agénor et al. ascertained that most participants recognized that testosterone is ineffective as contraception and clinically proven methods were necessary for pregnancy prevention. 16 On the other hand, in a study with 20 participants, 12 believed that testosterone use reduced their likelihood of becoming pregnant as a result of the belief that testosterone use may cause sterility. 22 A separate study found that thirty participants (16%) used testosterone as a contraceptive method, a third of which had been advised by healthcare providers to do so. 23

Fertility Preservation

Most TG people desired to become parents. 10,23-24 They indicated primary care doctors and endocrinologists as their primary sources of information surrounding fertility preservation (FP). 18,23-25 Nevertheless, a third of patients stated that medical professionals did not adequately address their FP goals or did not ask about their fertility desires. One-third of patients would be interested in a consultation with a reproductive endocrinologist if offered. 23-24

Referred barriers for FP were mainly the cost of treatment, discontinuation/delay of hormonal therapy, or worsening of gender dysphoria with treatment/pregnancy. 23-25 Even though becoming a parent is a frequent desire, 66% of TG people had no intention to pursue FP, and about 12% desired to do so. 24

Twenty percent of TG people would state that having biologically related children was important, versus 43% who did not. Adoption was only considered by 17%, and 40% did not contemplate adoption. 24 Indeed, not caring to have a biological child, followed by being too young were the most common reasons for declining FP.18 Desire for fertility preservation was not influenced by any individual factors, including gender identity, race/ethnicity, or age. 24

Two to six percent of TG patients requested a referral for FP. Additionally, 3% had undergone FP, the majority of whom had performed sperm cryopreservation. Furthermore, Vyas et al. analysed the decisional regret considering FP in TG individuals. Decisional regret was moderate to severe among those who had not yet undergone FP and were unsure if they would. A firm decision to pursue or not pursue fertility treatment was associated with mild decisional regret. 24

Cervical cancer screening and prevention

According to Rahman et al., TG people had access to a primary care physician akin to cisgender people, nevertheless only a minority had seen a gynaecologist compared to ciswomen. TGM and TGF had significantly less correct knowledge about HPV, and only 9% of TGF had received the HPV vaccine. One-third of TGM had never received a pelvic examination or cervical Pap smear in their lifetime. Abnormal cervical results were received in 15% of TGM and 24% had contracted STIs within the past year. Additionally, herpes differentially impacted ciswomen, with no reported cases in TG. 26

Provider-level issues

In a study involving physicians, psychologists, master-level mental health providers, and non-physician healthcare providers (all providing care to TG individuals), it was determined that overall fertility-related knowledge was high. The level of knowledge was comparable among the different types of providers, although physicians were most likely to discuss fertility with patients. 27

Providers recognized that lack of education (with education mostly based on information from conferences, word of mouth, and trial and error), provider discomfort, judgments or assumptions, and the need for trauma-informed healthcare have impacted their pregnancy prevention care practices. 17

One study discussed providers’ fear of offending patients and nervousness around addressing pregnancy prevention care with TG patients. 17

Fix et al. outlined the perspectives of several SRH providers concerning contraceptive methods. Providers suggested that the alleviation of dysphoria, amenorrhea and being free of hormones are the most valuable characteristics to patients. 28

Several strategies were highlighted as a means to improve SHR care in the TG population, such as the development of educational materials and their dissemination, collaborating with the TG population to better cater to their needs, and developing specific training for healthcare providers in these matters. 28

Discussion

This systematic review is the first to summarize the evidence on the sexual and reproductive health of TG people.

Few guidelines are aimed at providing primary care practitioners with tools and knowledge to meet the needs of TG patients. Colleagues from the University of California, San Francisco created the Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People. They thoroughly explored issues regarding hormone therapy, comorbidities, cancer screening, and surgical planning, but nothing regarding contraception in this special population. 29

First and foremost, contraception in TG people can have many purposes, including the prevention of pregnancy, and frequently exerts an impact on the gender dysphoria and psychological distress experienced by TGM as menarche occurs, as this is the primary manifestation affirming that their body does not function according to their gender identity. 30 Consequently, health providers should be able to acknowledge the diverse psychological factors involved in contraception choice, such as gender dysphoria, but also the fear of getting pregnant.

To address those issues, TGM need to be aware that they are at risk of being pregnant. A great percentage of TG patients still believe that testosterone may be used as a contraceptive method, which prevents the recognition of their pregnancy risk. 17 Therefore, primary care providers need to be prepared to counsel and prescribe the best contraceptive methods, adequate to the individuality of each patient, but also to educate TGM about family planning. 23

A recent study determined that TG youth gathered SRH information from school, providers, peers, romantic partners, and online sources. It was ascertained that school curricula were not sufficiently adapted to fit TG sexual education needs, and some important topics were suggested: gender dysphoria, gender-affirming interventions, fertility, and contraception. 12

Contraception in TGM covers a wide range of me-thods, from condoms, and birth control pills to IUDs. To effectively counsel TGM, better data is needed on the minutiae of the different birth control pills (to alleviate gender dysphoria), the impact of testosterone on fertility, and the effects of low-dose contraceptive hormones on exogenous testosterone use. 23

The lack of formal education among providers plus the discrimination TG people face contributes to the rising of myths and misinformation among the population. These beliefs influence contraceptive and SRH care experiences, mostly negatively, although the intention of avoiding pregnancy is maintained. 16-17,19

Steps should be taken to improve sexual health curricula in schools and medical faculties, mitigating the misinformation that drives the contraceptive choices of the population, particularly in TG communities.

Fertility preservation should be an integral part of an SRH consult. Most TG people desire to be parents, but the question of whether biologically or not is mostly undefined. Surprisingly, during the transition process, only a minority of patients were referred to an endocrinologist. On the other hand, some TG people consider themselves too young or do not care about being parents. This disconnection may be explained by a focus on the transition at the time, in detriment to reproductive planning. 24-25 When analysing the decisional regret scale towards fertility, TG people who were interested in a consultation with a reproductive endocrinologist expressed moderate-to-severe regret. This was associated with higher decisional conflict, lower satisfaction with a decision, fear of adverse physical health outcomes, and greater anxiety levels. 31

Indeed, a study revealed that 37.5% of TGM would have considered cryopreservation of gametes had the technique been available during transition. 32 Vyas et al. inferred that consultation with a fertility specialist may decrease decisional regret. 24 A reproductive endocrinologist may be able to provide more detailed counselling and consequently allow TG to make a conscious and informed decision surrounding fertility preservation.

Cervical cancer screening and prevention should be part of the standard care of any individual identifying as female or who was born as a female. Nevertheless, TG people do not routinely undertake pelvic examinations or Pap smears.

Two factors seem to increase the prevalence of physical examination of the TG population: on one hand, having access to a gynaecologist, and on the other hand, perception of the importance of HPV screening. The paucity of knowledge about HPV among TG people needs to be addressed, allowing for the rise of HPV immunization, and genital screening and, ultimately, raising awareness about the importance of SRH consults. Additionally, previous negative experiences may influence TGM’s willingness to ask for or receive a cervical Pap smear or pelvic examination. 33

No papers were retrieved about breast and prostate cancer in the TG population, even though this is a major concern for patients and doctors alike.

In the Portuguese paradigm, HPV screening and pelvic examination are mainly performed by primary care physicians - following the organized populational screening. 34 This greatly contrasts with other regions, where HPV screening almost exclusively depends on secondary care.

By their (almost) all-encompassing reach to the community, family doctors are in a privileged position to offer cancer screening to minority populations (including TGM), which present with most invasive cervical cancers. 35-37

Primary care physicians must be mindful of the healthcare barriers and discrimination in screening for cancer in TGM. Delay in diagnosis and treatment occurs if the screenings are not executed at the right time. Even if patients have undergone gender confirmation surgery, there is a residual malignant risk related to their assigned sex at birth. 13

According to Giffort et al., healthcare providers avoid some SRH conversations with TG people for many reasons, such as the lack of formal education and clinical guidelines as well as misguided beliefs about pregnancy risk. 38

In a survey of general internal and family medicine clinicians, it was ascertained that the majority were willing to provide routine care and cervical cancer screening tests to TGM. It was observed that this willingness to provide care decreased significantly with age and the willingness to provide cervical cancer screening was higher among family physicians and those who had met a TG person. Although promising, these findings demonstrate that age, personal experiences, and biases affect doctors’ willingness to provide care to the TG population. Ideally, every doctor should be willing to provide routine care to all patients - including those who identify as TG. 15

Clinical practice guidelines with specific indications towards the TG population are needed, allowing for inclusive care and cancer screening in the TG population.

Regarding STIs, a recent scoping review revealed that only 14% of 700 existing articles concerning the TG population focused on sexual health, and HIV is by far the best-studied infection, with 96% of articles reporting only laboratory results. 39-40 Additionally, most research papers exclusively address sexual risk behaviours among TG people.

Indeed, when considering non-HIV STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, viral hepatitis, and herpes simplex virus, the data is mainly self-reported. Consequently, it is difficult to know their true prevalence. Again, the need for specific STI screening guidelines and awareness among TG is reiterated.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review is the first to summarize the evidence on the sexual and reproductive health of TG people. This review has comprehensively synthesized and analysed in depth 13 cross-sectional and qualitative studies, following Cochrane guidance and PRISMA statement to ensure the methodology was robust and systematic. Evidence was summarized and its quality evaluation was based on validated instruments.

There are some limitations to consider in this study. The results of this review may have been affected by selection and recall bias affecting the included papers. The authors have also identified aspects concerning recruitment methods, sample size, participant demographics and race/ethnicity, TG representation, and the self-reported character of data in the included publications as important limitations. It may also be argued that the interventions described do not reflect the full range of services available to the TG population.

Further research

This systematic review outlines the need to develop guidelines for TG sexual and reproductive health, where the diverse aspects of contraception are considered. Across the included studies, the authors specifically point out the need for research on contraceptive methods, pregnancy prevention counselling, the impact of testosterone therapy on contraception, and cancer and STI screening among TG people.

Conclusion

Family doctors are the first point of contact within the healthcare system, connected with the entire population from birth until death and, as such, are in a privileged position to provide care to disadvantaged populations. Considering secondary care has limited reach to the TG population, primary care assumes a vital role in the management of their health concerns.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization, SMF, AMP, and RAA; methodology, SMF, AMP, and RAA; software, SMF, AMP, and RAA; validation, SMF, AMP, and RAA; formal analysis, SMF, AMP, and RAA; investigation, SMF, AMP, and RAA; resources, SMF, AMP, and RAA; data curation, SMF, AMP, and RAA; writing - original draft, SMF, AMP, and RAA; writing - review & editing, SMF, AMP, and RAA; visualization, SMF, AMP, and RAA; supervision and project administration, SMF, AMP, and RAA.