Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.9 no.1 Faro 2013

Strategy, investment, behaviour and results

Estratégia, investimento, comportamento e resultados

Richard Pettinger

University College London, r.pettinger@ucl.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

The drives to make effective business decisions are essentially generated by the need for human (as opposed to professional or expert) comfort, and therefore informed and influenced by the need to make outcomes as predictable and assured as possible, and that those in key organisational and managerial positions turn to the behaviours that they have learned over the entire period of their lives, rather than to professional expertise, knowledge and influence that are available to them in their organisations. This comfort and assurance is in turn driven by the fact that it is corporate rather than personal resources that are at risk and so on the face of it ‘there is little that can go wrong’. This is much more comforting at a human level, and much less dependent on the expertise of others, than relying on emerging techniques and tools such as business and web analytics, which are harder to use professionally, and require dependence and trust at a human level. Influences on behaviour can be seen in the form of:

- Bullying, pulling rank and using power of personality and position to get decisions through an implemented

- Employing uncritical people in senior positions to reinforce comfort and assurance.

Influences on decisions can be tracked through relating intended outcomes to actual results and then in turn evaluating the key drivers of the decisions present at the time. The conclusions are that a body of knowledge and understanding in this area needs to be developed and implemented. A body of learning and understanding is required to be brought to the fore, so that those who arrive in top senior and critical positions can undertake some specialist development in this critical area before taking key decisions based on their own preferences and personality and position.

Keywords: Strategy; decision making; investment; organisational behaviour; managerial behaviour; risk.

RESUMO

Os impulsos para tomar decisões de negócio eficazes são gerados essencialmente pela necessidade de conforto humano (em oposição ao profissional ou especialista) e, portanto, informados e influenciados pela necessidade de tornar os resultados tão previsíveis e garantidos quanto possível. Por outro lado, aqueles que se encontram em cargos chave de gestão e organizacionais pautam a sua conduta por comportamentos que aprenderam ao longo da vida, ao invés de recorrerem à experiência profissional, ao conhecimento e à influência que estão disponíveis para eles nas suas organizações. Este conforto e segurança são, por sua vez, impulsionados pelo fato de que são recursos empresariais e não pessoais que estão em risco e assim "não há muito que possa dar errado". Isso é muito mais confortável ao nível humano, e muito menos dependente da experiência dos outros, do que depender de técnicas emergentes e ferramentas, tais como analítica de negócio e analítica web, que são mais difíceis de usar profissionalmente, e necessitam de dependência e confiança ao nível humano. Influências sobre o comportamento podem ser vistas na forma de:

- Imposição da sua vontade, usando o poder da personalidade e a sua posição fazer prevalecer e implementar as suas decisões.

- Empregar pessoas acríticas em altos cargos para lhes reforçar o conforto e a segurança.

Influências sobre as decisões podem ser rastreadas através do relacionamento dos resultados pretendidos com os resultados reais e, em seguida, por sua vez, avaliar os principais impulsionadores das decisões presentes no momento. As conclusões são de que um corpo de conhecimento e compreensão nesta área precisa de ser desenvolvido e implementado. É necessário o predomínio da aprendizagem e do conhecimento para que aqueles que chegam aos principais cargos de responsabilidade possam aprofundar os seus conhecimentos nesta área crítica antes de tomarem decisões importantes com base na sua posição, nas suas próprias preferências e personalidade.

Palavras-chave: Estratégia, tomada de decisão, investimento, comportamento organizacional, comportamento gerencial, risco.

Introduction

A major part of business strategy and strategic management is deciding on initiatives, proposals, direction and priorities. It follows therefore that before decisions are actually taken, the various alternatives present and available have to be assessed, appraised or evaluated in terms of their potential. The purpose of this paper is to identify and begin to determine the context in which decisions are taken, and to begin to evaluate the different pressures and drives (especially the behavioural drives) that are present when strategy is being developed and implemented. This is to inform the debate around the development and professionalisation of this key area of management practice and expertise.

Context

Business ventures, new products, services and projects, and investments are appraised and evaluated on the basis of returns on investment, returns on capital employed, and contributions to organisation product and service development, reputation and standing. It is additionally essential that everyone involved in decision-making has a full understanding of what is possible, feasible and practicable in terms of organisation resources, capability, willingness and commitment.

In practice, all of this is integrated into decision-making processes. For example, an investment made with the purpose of generating a 10% financial gain over a given year is likely to produce enhanced confidence and reputation if the target is met; while if it fails to meet the target, this may call into question wider aspects of confidence and capability in the decision-making processes, and in the methods used to arrive at the decisions.

Finally, there is a human as well as managerial drive to make decisions as assurable, certain and predictable in outcome as possible.

Strategy

The common factor in all successful and effective strategies is clarity. It is therefore essential to have at the outset a clear core foundation or generic strategic competitive position, understood and accepted by all of the organisation’s key stakeholders: staff, customers, suppliers, financiers and backers, and the public at large.

Porter (1980, 1986) identifies the following generic positions from which all effective and profitable activities arise. These are:

- Cost leadership/cost advantage: the drive to be the lowest cost operator in the field; or failing this, to seek the best possible cost advantage in order to be able to compete on

· this basis. To be a cost leader, investment is required in state-of-the-art production technology and high quality expert and committed staff. Cost leadership organisations are lean in form with small hierarchies, large spans of control, and the majority of staff concentrated on frontline activities. The drive for cost leadership and cost advantage is essential in any approach that seeks market presence and effectiveness in products and services for which price is the overriding benefit to customers.

- Differentiation, brand leadership/brand advantage: offering otherwise homogeneous products on the basis of creating a strong image or identity. Investment is required in marketing, advertising, developing brand strength and loyalty and managing assured outlets and distribution (including web-based distribution). Returns are generated over the medium to long-term as the result of generating and developing brand loyalty and identity leading to extensive repeat purchases on the part of the customer base.

Organisations that seek cost or brand leadership or advantage need to assure their focus. ‘Focus’ here means that organisations need to identify the core customer bases served and concentrate on delivering products and services in such ways that are of value to them. In this context, Porter identifies:

· mass focus, concentrating on mass market products and services;

· narrow focus, concentrating on identifying and delivering assured levels of products and volumes of services to specific customers identified.

Porter additionally identifies:

· cost focus, whereby niches are evaluated in terms of the ability to serve them using cost leadership and advantage;

· brand/differentiation focus, in terms of identifying niches requiring branded and perceived high quality products and services.

Having clarified the foundation position, strategic initiatives that develop this can then be decided upon and implemented as follows:

- Growth strategies: measured against pre-set objectives, whether in terms of income, profit margins, shareholder value, reputation enhancement, income per customer, income per location, income per product/service, market share development, sales volume development, and the implementation of new products and services.

- Retrenchment strategies: taking the form of withdrawal from niches or peripheral activities, sales of assets, product and service divestment, and a return to concentration on core activities.

- Diversification strategies: where organisations take the conscious decision to move into new markets and activities, sometimes in spite of the fact that they have no particular expertise or knowledge in the new chosen field. It is therefore essential that this knowledge and understanding is acquired before diversification is undertaken.

- Market domination: in which companies and organisations seek domination as the result of: sales volumes, largest number of outlets, technological domination, expertise domination, or a combination of all of these. Domination can also arise as the result of being the majority supplier, the largest single player, or the member of an oligopoly or cartel.

- Incremental strategies: the view of incremental approaches is popular with those who argue for genuinely rational approaches to long-term business development. The rationale is that a genuine long-term strategy is actually impossible to achieve given the nature of business practice and activities. It is therefore essential to commit time, energy, resources and expertise to managing the development of strategy on a continuous basis, responding to opportunities that suddenly become available.

Strategies for failure

Pettinger (2002) identifies the conditions under which ‘strategies for failure’ may exist, as follows:

- Static or declining sales: rising costs.

- Static or declining quality: rising prices.

· Increases in customer complaints in branded and differentiated organisations.

· Increases in fixed and variable costs in cost leadership/advantage organisations.

· Declines in quality of service in branded/differentiated organisations and with branded/differentiated products and services.

- Cost increases: declining revenues/income/profits.

These conditions do not necessarily lead to organisation failure. They are however triggers for strategic evaluation in terms of product and service quality and volume deliveries; and in terms of managing the organisation internally.

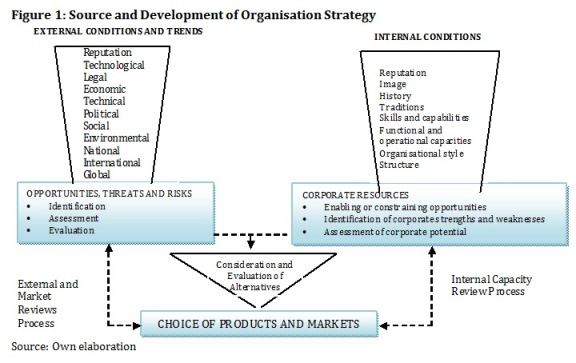

As long as clarity can be achieved in both the core position, and also the positions from which it is developed, then the strategy process may be mapped as follows (see Figure 1).

Investment

Investment takes place alongside strategy. Investment is the process of committing time, energy, resources and money in the expectation of returns; and these returns require defining as precisely as possible.

There is always a financial drive at the core of returns on investment. Additionally, returns on investment are measured in terms of:

· gains and losses in reputation and confidence;

· incremental returns, in which initiatives are undertaken in the expectations of derived and future returns;

· if an organisation chooses to work in a particular sector, then it must be prepared to accept the returns that are on offer; if an organisation requires specific returns, then it must operate in those sectors in which those returns are possible.

Because of the nature of business and organisational activities, it is usual to define returns within ranges or parameters. These ranges and parameters require extensive evaluation. This is to ensure that when decisions are taken to proceed, organisations and their managers have the clearest possible knowledge and understanding of what they have chosen and why, the opportunities and consequences, and where and how what is proposed is likely to lead.

A strategic management approach to the effective consideration of ventures and proposals requires consideration of the following factors.

· Assessment of the range of returns possible, both positive and negative and in financial and non-financial terms.

· Attention to the behavioural aspects of the venture or proposal (eg who is driving it, who is opposing it and why).

· Assessments of the risks involved in the new venture or proposal.

· Definitions of success and failure; and assessment of the consequences of success, and the consequences of failure.

It is at this point that general levels of acceptability or otherwise of involvement in the venture or proposal will become clear. Additionally, the organisation now ought to be able to determine the length of time for which investment is required, and the extent to which this may contract, and especially the extent to which this may extend.

The general levels of acceptability now need full definition, so that good ideas are not discarded before full evaluation, and so that bad ideas do not gain a life of their own because they look superficially attractive and viable.

It is also essential to determine at this point whether possible variations are going to be acceptable. For example:

if a return of 10% per annum is acceptable, and anything less is unacceptable, what is the attitude to an actual return of 9.9%? 9.5%? The likelihood, or otherwise, of hitting a target at the point of bare acceptability therefore needs further consideration;

· if a return of 10% is 'beyond the wildest dreams', and analyses then predict or strongly indicate that this is likely, it then becomes necessary to consider whether further funds or resources should be put into the particular venture or proposal;

· if a return of 10% is decided, then it needs to be clear why this figure was arrived at, and why it represents an effective return (why 10%, why not 9% or 11%).

In many cases it therefore becomes tempting (from a behavioural perspective) to set the boundaries of acceptability so wide that everything is at least satisfactory (Simon 1967).

Policy and direction

Policy and direction issues for particular ventures emphasise the needs to:

· ensure that what is to be done meets the organisation's overall strategy, direction, standards and values;

· integrate from a managerial point of view the new venture, proposal, product or service with everything else that the organisation is presently engaged on.

Conforming to present standards of policy and direction helps to ensure that:

· new ventures are not swamped by existing activities;

· new ventures do not swamp existing activities;

· organisations do not get led off down fashionable and faddish routes;

· organisations do not get drawn into the schemes of powerful and influential individuals just because of their power and influence – whatever is driven by powerful individuals must be for the good of the organisation;

The key point of reference is that organisations stick to what they know, understand and are best at. If it does become essential to venture into the unknown, then a critical part of the commitment is to ensure that everything possible is known and understood about the new venture, location or environment, and its potential for supporting enduringly viable business, in advance of any commitment.

Priorities

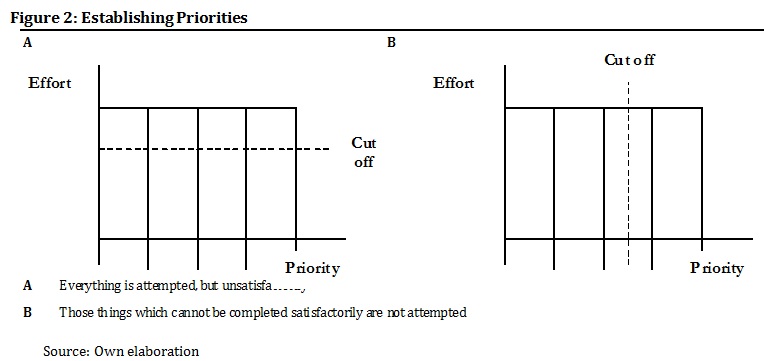

Clarity of organisational and strategic priorities arises from the clarity of the strategic position itself. Ideally, priorities are established to organise and ensure concentration of resources to best commercial or service advantage in the pursuit of long-term customer, client and user satisfaction. In practice, it is rarely possible to achieve everything desired or required. Two basic approaches are possible (see Figure 2).

There is nothing intrinsically right or wrong with either approach indicated in the above figure. The main issue at the outset is to be clear about which approach is being taken, and the opportunities and consequences of that choice.

Behaviour

How organisations and their people (collectively and individually) behave is critical to effective decision-making and implementation. A critical part of the strategy process therefore lies in knowing and understanding:

· the collective and dominant culture, attitudes, values and ethics present;

· the nature and influence of key dominant and powerful individuals and groups; and how they behave in relation to decisions that have to be taken

· the key drivers of decisions, whether behavioural or business driven (and where the balance lies between behavioural and business drives).

Collective and individual confidence on the part of everyone concerned is vital; it is impossible to convince others of a particular choice if this confidence is not present.

Collective confidence is always called into question when the organisation is led into a particular venture or direction by a key, dominant, powerful figure or group, without a fully justified business case alongside. Practical concerns and objections are overridden. Where the dominant group or figure have absolute faith that they have got their position right, they must be able to defend this, respond to concerns, and address questions without having to resort to forcing their position upon everyone else. Where the dominant interests are forcing through their own particular point of view for their own partial ends, ventures normally enjoy initial fleeting success, immediate high profile, and then rapid decline.

This is seen at its worst when top, senior powerful and dominant personalities use the force of their position or influence (as well as their personality) to drive something through that they are personally committed to (they may also be committed in the name of the organisation, but this becomes subservient to their own particular ambition). In extreme cases this can and does lead to bullying and harassment, victimisation of waverers and doubters, and marginalisation of anyone with expertise who tries to bring a rationale to the particular position.

Collective confidence and mutuality of interest are key aspects in the success or otherwise of partnerships and joint ventures. Those who engage in arrangements and agreements with other organisations must satisfy themselves that they are willing and able to work together, that the specific outcomes desired by all parties are capable of achievement in the situation, and that no dominant or key interest is going to take everything at the expense of the others involved.

Assessment of behaviour alongside the rationale for the intended course or courses of action identifies the extent to which the organisation is willing, as well as capable of implementing what is proposed.

Risk

A strategic approach to risk management requires that the components of risk and uncertainty that can (and that can conceivably) affect the organisation and its environment must be studied. This is so as to ensure that anyone in a top, senior or executive position understands the full range of issues that could conceivably arise.

The main factors to attend to are as follows.

· Assessment of sectoral trends: whether the sector is growing or declining.

· Knowledge and understanding of substitute and alternative products and services.

· Knowing and understanding social, political and economic issues, drives and restraints, and how these could conceivably affect supplier, buyer, consumer and investor behaviour.

· Evaluation of outcomes of particular ventures, including: identifying the best, medium and worst possible outcomes; and analysing and evaluating any actual or potential critical obstacles and incidents.

· Evaluating the capability to extricate oneself from the particular situation is required.

· Assessment and evaluation of the actual attitudes of staff to what is proposed; recognising the potential consequences of failure on supply or distribution sides.

· Scanning the macro environment for changes in regulation, transport and energy costs that could, or could conceivably, affect the overall competitive position.

Effective risk management has a range of early warning systems at its core. These early warning systems require:

· regular scouring and scanning of the environment as above;

· recognising signs of dissatisfaction among staff, customers, clients, suppliers and backers as early as possible;

· recognising early indications of organisational costs beginning to rise;

· recognising the effects, propensity and potential for technological glitches, and their effects on performance.

Most organisations have risk management policies in place. Over recent years, the volumes of disasters, the nature of corporate failures, and the costs involved have all contributed to the need to understand risk and its management as fully as possible.

A behavioural approach to risk requires that each of these points is attended to and evaluated. It is not enough to have in place risk management and assessment policies and strategies: the active attention to and management of risk is an essential part of managerial expertise, and a key priority in all effective decision making.

The key behavioural issues in risk management are essentially human rather than organisational, as follows:

· if people do not have to do something they will avoid it;

· if people do not like doing something they will avoid it;

· if people cannot be bothered to do something they will avoid it;

· if there is no discernible or tangible reward for doing something people will avoid it;

· if people are given the authority to do something they will do it (as they are not then responsible for the outcomes);

· if people know and understand that it is not their own resources or reputation that is at risk, they will do something;

· if people are ordered by those in authority to do something they will do it.

These become the critical areas of risk management implementation for everyone to know and understand and to attend to during decision making processes and the evaluation of strategy and new ventures and proposals.

The strategy/behaviour/risk mix

The implementation of organisational and business decisions that arise from determining a corporate strategy is founded on the basis of all of the complexities that organisational behaviour and approaches to risk produce. The key issues therefore become:

· what the organisation collectively and individuals want to do;

· the nature and position of key figures driving, restraining and vetoing particular courses of action;

· the extent to which risk is analysed and evaluated; and how these analyses and evaluations inform decision-making processes;

· whether or not those who have decision making authority are prepared to face the findings of risk assessments and the limitations placed as the result.

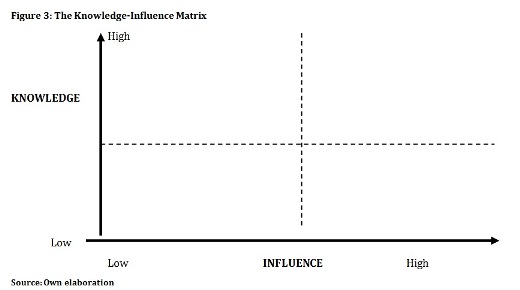

In each part of the process there is the potential for ‘human’ (as distinct from ‘expert’) intervention and influence. This potential is compounded when powerful and dominant figures are present, whether or not they have any knowledge or understanding of a particular situation or proposal (see Figure 3).

If effective strategy is to be implemented, and if effective and enduringly viable decisions are to be taken, then the gaps in knowledge and the sources of influence have to be fully assessed. In particular, it is a key part of effective professional management development, that the balance between expertise and position, rank and authority is known and understood as the catalyst for decision making.

Decision-making

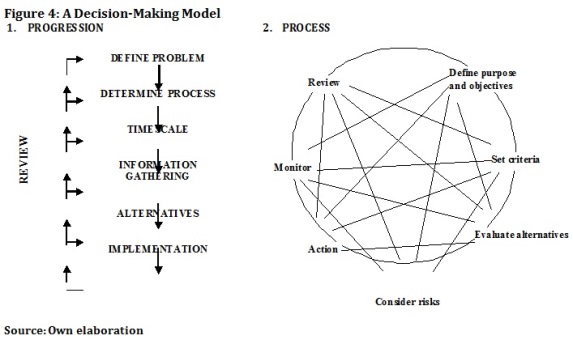

Decision-making is both progression and also process. Decision-making is based on a combination of:

the clarity with which issues and initiatives are defined;

· the determination of the processes and progressions to be used;

· the length of time that is available for the decision to be taken;

· the availability of information, and especially the availability of information within time constraints;

· the alternatives that are available; and evaluation of alternatives must include the choice of doing nothing;

· implementation: the point of action at which the decision is actually taken (see Figure 4).

Purpose: to draw the distinction between the two elements of progress and process. The former is a schematic approach; the latter is that from which the former arises, and which refines it into its final format. Effective and successful decision-making requires the confidence that is generated by continued operation of the process.

Into this is then added the human and behavioural influence: in simple terms, what do those who have to take the decisions want to do?

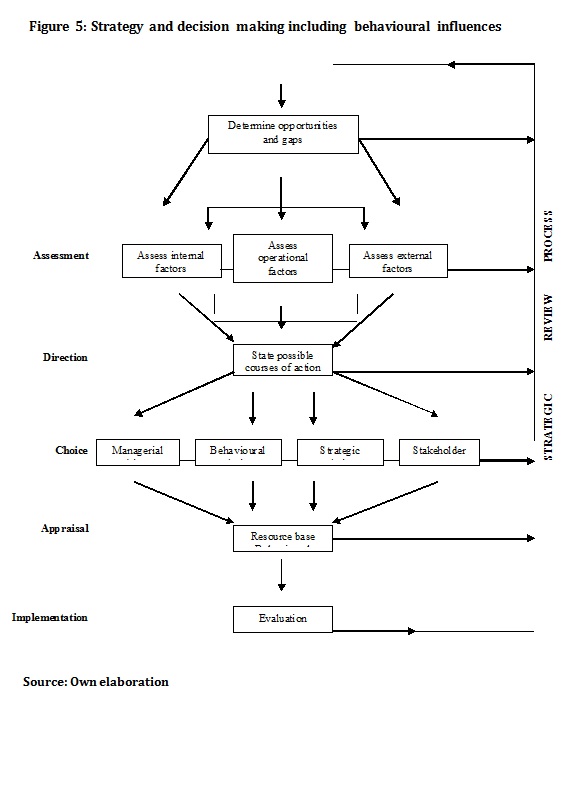

The wish or desire is influenced by a range of human and organisational behavioural factors. Handy (1996) asserts that people have a much greater comfort in risk taking if they know and understand that they are a part of a collective rather than individual effort. Milgram(1974) reinforces this in stating that people will do things that they would not otherwise do, as long as they are either given authority or rank to do it, or that the consequences of their actions are removed. Heller (1996) states that people have an almost infinite collective capacity for denial when things go wrong. In extreme cases, human patterns of behaviour including bullying, the use of rank, force of personality, and position in order to get decisions accepted and implemented are also used. Bevan (2006) asserts that those disposed to take decisions using personal and position power, tend to surround themselves with others who will not (in public or formally at least) question what is to be done (though they may speak up after the event, and especially after the powerful and dominant personality has moved on). If the dominant behavioural elements of risk are then added, the propensity for rationally driven decisions is greatly diluted. If this is the case, then a decision-making process looks like this (see Figure 5).

Behavioural pressures and influences on critical decisions

Organisations have series and patterns of decisions that are unique to them at all times (Andrews 1971). However, there are classes of decisions that are common across all organisations, meaning that at some point everyone is faced with more or less universal issues that have to be addressed as follows:

- whether to buy and own technology and equipment or to lease it;

- whether to outsource particular activities or retain them in-house;

· whether to enter into new ventures on the basis of return on investment, or to enter on the basis of collective and individual vanity, prestige and triumph;

· whether or not to buy up critical resources, and the organisations and sources that presently own them;

· whether or not to become involved in merger, acquisition and takeover activities;

- whether or not to enter into new markets, locations and activities;

· establishing the rationale for entering into partnerships and joint ventures;

· whether or not to take decisions on the basis of damage and limitation to competitors, rather than for direct organisational advantage;

· determining the rationale for developing new products, services and ventures.

At the points at which each proposal is considered on an individual basis, there will be data that supports the idea, and risks and contextual factors that have also to be considered. A critical matrix may then form from this as follows.

- the decision is rationally acceptable and behaviourally acceptable;

- the decision is rationally acceptable and behaviourally unacceptable;

- the decision is rationally unacceptable and behaviourally acceptable;

- the decision is rationally unacceptable and behaviourally unacceptable.

The key areas are therefore:

· where the decision is rationally acceptable and behaviourally unacceptable;

· where the decision is rationally unacceptable and behaviourally acceptable.

Where the decision is rationally acceptable but behaviourally unacceptable, decisions are not then taken because those in key positions find themselves unable to impose what is right for the organisation and its stakeholders. In these cases, the strategic response ought to be incremental advance, making small changes and developments where possible, while at the same time looking for opportunities to change the wider situation more radically. In some cases also, external consultants become involved, so that it is they and not the organisation’s managers who are recognised and identified as the causes of any cataclysmic change.

Where the decision is rationally unacceptable but behaviourally acceptable, what is proposed is bad for the organisation but good for and/or demanded by, either top or senior management, or other powerful and dominant stakeholders. In these cases, the behavioural drive rather than the business drive is the dominant force, and business issues and rational analysis are set aside. The behavioural drive is then compounded and energised by the powerful and dominant personalities, stakeholders and vested interests concerned. Anything that might produce a clearly indicated risk, brake or barrier to progress is dismissed. Risks are either not analysed, or else they are ignored. Resources, capability and willingness are assumed to be present. Logistical and operational capacities are taken for granted. Anyone opposing the proposition on the grounds of rationale or expertise is marginalised or ostracised. The required organisational, environmental and operational analyses are not carried out (and in some cases this can extend to legal due diligence). The result is that the organisation does what its top, senior and most powerful individuals and groups want, whether or not this is in the organisation’s best interests.

Changing priorities

Problems and issues arise when the organisation, for whatever reason, changes its priorities. Changing priorities have both behavioural and also strategic drives and influences.

New top senior and key personnel bring in their own agenda, ideas, expertise and drives to particular situations. Key personnel may either cancel or modify what is presently being done, or else take it in their own preferred direction. This may lead to cancellations, delays and modifications; to existing ventures being rushed along, so that the new generation can be brought on; or they may be given an additional profile so that the new key person is seen to gain immediate results. Whichever is the case, provided that this is well understood and accepted, there is no problem. One part of product and service development becomes an investment in false-starts, accelerations and cancellations, and this happens in many organisations and situations.

Cancellations and changes can be a serious problem where it is clear that the new key member of staff is doing things to make their own mark rather than developing the totality of organisation effectiveness.

The activities and influence of consultants also bring in their own agenda, and who often feel the need to demonstrate a physical and visible impact, as well as (or as part of) their proposal for the development of the organisation and its products and services. Following the lead given by consultants may lead to changes in priorities that are fully effective and required by the organisation; or they may again dilute the effectiveness of what is being done. And the high fee levels charged and profile accorded by many large consulting firms combine to put great behavioural pressures on organisational strategic managers to follow prescriptions and recommendations.

Changes in markets and environments, causing it to become apparent that present levels and ranges of products, services and performance are no longer adequate, acceptable or required. Gaining a return on investment in such circumstances may cause rethinking on prices, costs and charging structures; divesting particular ventures, products and services; or generating the capacity (increases and decreases) to meet new levels of demand.

Towards effective decision-making processes

To bring the threads from above together, in practice decision-making processes need to match resources and capability with:

· feasibility, in which the levels of return required or demanded have to be assessed in terms of whether they are possible at all, the likelihood of these being secured, and the consequences if something does go wrong;

- risk management and attention to the full context of what is envisaged;

· willingness, in which the collective and individual behaviour of all those involved, and the organisation's collective will to follow chosen courses of action through to their conclusion must also be tested.

Both strategic and behavioural factors that reinforce and dilute confidence and commitment must be identified and evaluated in full. This must include a full evaluation of the past history of returns on investment on specific ventures, initiatives and new products and services development; the extent to which each of these have met targets and wider expectations, and the reasons for successes and failures. These reasons then need to be classified as strategic or behavioural, so that the true driving and dominant forces can be assessed.

There must also be a detailed evaluation of present, prevailing and influential attitudes to enduring commitments. This requires organisational and collective honesty. If an organisation has a present or recent history of pulling out of ventures the moment that tricky or unforeseen sets of circumstances arise, then this must be acknowledged; and if this is the preferred and determined way of working, then it becomes an understood and accepted constraint.

The overall approach needs to reflect known, understood and accepted ways in which choices are made, requiring an understanding that whatever is chosen carries consequences as well as opportunities.

This in turn reinforces the need to define precisely at the outset the returns desired, required and demanded. If 'synergies', 'economies of scale', and 'critical mass' are sought, then these should be calculated, projected and forecast precisely.

In practice, some decisions can be reversed, others cannot. Others can be changed at great cost and at the expense and acknowledgement of resources wasted. Other decisions can be changed to take advantage of new opportunities that have subsequently arisen; and in these cases, the resources consumed (and lost, if that is the case) on the initial venture might be acknowledged in calculating the returns on the subsequent initiative.

Dixon (1996) makes the following additional points.

· Not all outcomes of investment decisions can be assessed in profit and loss terms. Those responsible for decision-making might feel that they would rather invest in locations, products and services where returns are lower or less assured, but where economic and social systems are more stable;

· Full knowledge of the range of options available at any given time may not be complete. This may be due to a lack of market or environmental research. It may also be caused by internal factors - e.g. the failure of managers in one part of an organisation to provide information required by those in other parts;

· The outcomes of investment decisions especially are never certain. Above all, they are influenced by uncertainties about the continued strength of the economy, political, social and economic changes;

· Those responsible for making decisions may lack capability and expertise in the area; or if they have this expertise, may be prevented from using it by those with lesser knowledge but greater influence in the organisation.

Conclusions

As stated in the introduction, the purpose of this paper is to identify and determine the actual context in which decisions are taken, and to begin to evaluate the different pressures and drives present, and the extent to which these drives influence what is actually done. In summary these are:

· commercial and organisational drives in terms of what is best for securing immediate and enduring viability and profitability;

- the stated and actual position in relation to risk;

· behavioural drives in terms of how people think, act and react, collectively and individually, and from a human as well as professional and occupational point of view.

The extent, prevalence and influence of each set of drives have to be known and understood in every case. These drives have then to be evaluated and assimilated into decision-making processes so that strategy and its implementation in the name of immediate and enduring viability and profitability remain the single priority. This in turn means that risk and its management, the processes for the implementation of strategy, and the decision-making processes themselves, are all consciously concentrated towards serving the organisation’s interests; other interests must be either subservient to, or else capable of harmonisation and integration with, what is best for the organisation.

Such a step, and the knowledge and understanding that goes with this, ought to be a key driver towards a number of goals, as follows:

· the effective development of present and future generations of management and their expertise; and the nature and levels of knowledge and understanding needed in order to lead, direct and make viable the organisations of the present and the future;

· knowledge and understanding of how organisations actually work (as distinct from how people would like them to work, or indeed how they think they work);

· knowledge and understanding of how decision making processes actually work (as distinct from what decision making process are);

· knowledge and understanding of why things go right and wrong when organisational and strategic decisions are taken.

If this were developed, it would be a key step towards the overall professionalisation of management.

Professions and the Professionalisation of Management

The 'classical' professions are held to be medicine, law, the priesthood and the ‘profession of arms’ (the military). The following properties were held to distinguish these occupations from the rest of society.

- Distinctive expertise: not available elsewhere in society or in its individual members.

- Distinctive body of knowledge: required by all those who aspire to practice.

- Entry barriers: in the form of examinations, time serving, learning from experts.

- Formal qualifications: given as the result of acquiring the body of knowledge and clearing the entry barriers.

- High status: professions are at the top of the occupational tree.

- Distinctive morality: for medicine, the commitment to keep people alive as long as possible; for law, a commitment to represent the client's best interests; for the church, a commitment to godliness and to serve the congregation's best interest; for the army, to fight within stated rules of law.

- High value: professions make a distinctive and positive contribution to both the organisations and individual members of the society.

- Self-regulating: professions set their own rules, codes of conduct, standards of performance and qualifications.

- Self-disciplining: professions establish their own bodies for dealing with problems, complaints, and allegations of malpractice.

- Unlimited reward levels: according to preferred levels of charges and the demands of society.

- Life membership: dismissal at the behest of the profession; ceasing to work for one employer does not constitute loss of profession.

- Personal commitment: to high standards of practice and morality; commitment to deliver the best possible in all circumstances.

- Self-discipline: commitment to personal standards of behaviour in the pursuit of professional excellence.

- Continuous development: of knowledge and skills; a commitment to keep abreast of all developments and initiatives in the field.

- Governance: by institutions established by the profession itself.

In absolute terms 'management' falls short in most areas. Formal qualifications are not a prerequisite to practice (though they are highly desirable and evermore sought after). Discipline and regulation of managers is still overwhelmingly a matter for organisations and not management institutions. There is some influence over reward levels and training and development. Measures of status and value are uneven. Management institutions act as focal points for debate; and they also have a lobbying function. They do not act as regulators.

There is a clear drive towards the professionalisation of management. This is based on attention to expertise, knowledge and qualifications, and the relationship between these and the value added to organisations by expert managers. Understanding decision making and how decisions are truly arrived at (whatever the rational and strategic approach may be stated to be) is a critical part of this professionalisation (in pursuit of this Handy (1996) proposed that all business school graduates should be required to take the equivalent of the Hippocratic Oath, thus committing themselves to best practice and high standards and quality of performance, whatever their own feelings and personal drives and priorities might be).

If the work around strategy, risk, behaviour and decision-making is seen in this way, as a basis for professional development, then much of the uncertainty about what is a key organisational and managerial priority is removed. An additional benefit is that the propensity for dominant personalities, individuals, groups and stakeholders to get their own way purely through force of presence is diminished. A greater understanding of how decisions are actually made will force organisations and their managers to face the real pressures and drives, and manage them rather than succumbing to them.

References

Andrews, K. (1971). The Concept of Corporate Strategy. Homewood: Irwin. [ Links ]

Bevan, J. (2006). The Rise and Fall and Rise Again of Marks and Spencer. London: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

Dixon, R. (1996). Investment Appraisal. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Handy, C. (1996). Understanding Organisations. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Heller, R. (1996). In Search of European Excellence. London: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to Authority: an experimental view. New York: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Pettinger, R. (2002). Contemporary Strategic Management. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Porter, M. (1986). Competitive Advantage. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Simon, H. (1997). Administrative Behaviour: A study of decision making processes in administrative organisation. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Article history

Submitted: 27 July 2012

Accepted: 07 November 2012