Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.15 no.4 Faro dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2019.150401

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Application of geomarketing to coastal tourism areas

Aplicación de geomarketing a zonas turísticas costeras

María Pilar Peñarubia-Zaragoza*, Moisés Simancas-Cruz**, Geraldine Forgione-Martín***

* University of Valencia, Department og Geography, Valencia, Spain, m.pilar.penarrubia@uv.es

** University of La Laguna, Department of Geography, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, msimancas@ull.es

*** University of La Laguna, ReinvenTUR Research Group: Tourist Renovation Observatory, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, geriforgione@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Geomarketing allows geographic units to be defined with a certain degree of homogeneity in terms of tourist preferences, behaviours, needs, expectations, buying and consumption patterns, and analogous attitudes. The result is a “territorial segmentation” of the demand in accordance with the geographic characteristics of tourism areas. The objective of this work is to analyse the strengths and weaknesses of applying geomarketing to the territorial segmentation of demand in coastal tourism areas. An empirical analysis of hotels specialising in family tourism in tourist accommodation establishments in Costa Adeje (Spain) is presented. The main conclusion is that the tourist accommodation variable is essential for any segmentation process and even for the micro-segmentation of coastal tourism areas. It allows similar consumers to be grouped in a market from a demand perspective based on shared needs, habits or attitudes and also from the supply side, according to territorial characteristics. Therefore, the territorial aspect is essential for public and private decision-making processes. This makes geomarketing an ideal technique for understanding tourists.

Keywords: Coastal tourism area, consumer behaviour, geomarketing, territorial segmentation, family tourism.

RESUMEN

El geomarketing permite delimitar unidades geográficas con cierto grado de homogeneidad en cuanto a las preferencias, comportamientos, necesidades, conductas de compra, expectativas, patrones de consumo y actitudes análogas de los turistas. Así, agrupa a consumidores similares dentro de un mercado desde el punto de vista de la demanda, sino también de las características de la oferta. El resultado es la “segmentación territorial” de la demanda. El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar las potencialidades y debilidades de la aplicación del geomarketing en los procesos de segmentación territorial de la demanda en las áreas turísticas de litoral. Se presenta un análisis empírico de los hoteles especializados en turismo familiar en Costa Adeje (España). La principal conclusión es que es que las cualidades (categoría, tipología, etc.) de los alojamientos turísticos son esenciales en cualquier proceso de segmentación, e incluso, la microsegmentación de los turistas en las áreas turísticas de litoral. Ello convierte al geomarketing en una metodología y una técnica adecuada para comprender a los turistas.

Palabras clave: Área turística de litoral, comportamiento del consumidor, geomarketing, segmentación territorial, turismo familiar.

1. Introduction

Several recent changes have initiated a process of continual evolution in coastal tourism. One of the most important is that tourists are now considered “clients” and are the focus of strategic decision-making processes carried out by businesses and public administrations. This gives them immense power, as their demands will define tourism supply. With this in mind, there are four basic issues that should be examined.

First of all, a key factor is now tourist satisfaction, understood as the feeling that the tourist has after comparing their experience with the expectations they had prior to the trip (Kotler, Bowen & Makens, 2005). Satisfaction directly affects the image of a destination and the probability that a tourist will return or recommend visiting to other potential tourists (Meng, Tepanon & Uysal, 2008). It is no longer enough just to gather information on the volume and origin of tourists, a deep understanding of the characteristics, attitudes, behaviours and perceptions of visitors is also needed to ensure that their experiences match expectations and achieve a high level of satisfaction.

Second, the coastal tourism market that for years had almost entirely specialised in “sun and beach” tourism, with little marketing included in business strategies, has become a heterogeneous product. This makes it necessary to diversify and differentiate the traditional (conventional) tourism supply by offering a range of products directed at very specific market segments. Moreover, tourism destinations can only adequately satisfy certain kinds of demand, because their resources only interest certain segments. In this sense, consumers visiting a specific area tend to have similar preferences, behaviours, needs, expectations, buying and consumption patterns, and attitudes.

Third, the profile of tourism consumers has changed; they are now multi-consumers, engaging in different activities that fragment their visits. Moreover, because they have access to much more information they can thoroughly examine existing offers and make more rational choices. The result is an independent tourist who is more involved in planning and organising their trips and choosing the elements that make up the tourism product they consume. They are also more active and want to take a leading role in their experiences, which includes demanding different products and “tailor-made” services. Moreover, they heavily use information technologies before, during and after their trips. Therefore, today’s tourism consumer is “in charge”, and has a major influence on what destinations offer.

Finally, although tourist accommodations are still the true “assets” of tourism destinations, the strategic importance of nearby attractions, services and other resources are becoming more and more relevant, because they provide the experiences and authenticity that tourists are searching for. This makes it necessary to retire the term “amenities” that has been used until now to refer to them, because, in some cases, they have become the main factor attracting tourists, as well as an element that generates the experiences that follow the current trend of “selling experiences, rather than products” (Vogeler & Hernández, 2002).

All of the above reveals that while understanding tourist consumption behaviour is essential for market segmentation, a strategic pillar of marketing, the territorial variable must also be taken into consideration, not just for its influence on behaviour, but also for its capacity to characterise groups (Alcaide, Calero & Hernández, 2012). It allows for the identification of territorial units that present a certain degree of homogeneity in visitor behaviour, motivation, tastes, attitudes and responses to the services offered at a destination and, therefore, the tourist profile. The result is a process of “territorial segmentation”. A suitable methodology and technique to do so is known as “geomarketing”. To this end, empirical evidence regarding tourist accommodation establishments in Costa Adeje (Tenerife, Spain) specialising in family tourism is examined.

2. Territorial segmentation of tourism areas

Choosing a tourism destination is directly influenced by various individual preferences (Aznar & Nicolini, 2007) that make up the specific profile of each potential visitor (Portillo, 2002). Examining how clients behave when buying products and services reveals a unique and highly complex process involving a great variety of factors that make it extremely difficult to obtain a proper understanding of tourists. Nevertheless, because of its importance, it is necessary to study their behaviour in order to adequately plan the tourism sector. In this regard, Martin et al. (2012) suggested that the most sought after information had to do with the profile of the demand, followed by analyses of the supply and competence and innovation.

Moreover, “many consumers see tourism as the continuous accumulation of experiences, which is obtained by visiting a variety of destinations and avoiding repeat visits, despite the fact that they are purchases that require significant involvement” (Escobar & González, 2011: 253). The growing number of factors that influence the purchasing behaviour of tourists considerably increases consumption classifications and makes their modelling more difficult.

Technological innovation over the past decade has significantly changed consumer behaviour. This new tourism paradigm is characterised by deep changes in both supply and demand, reflecting a social paradigm that can be referred to in various ways: post-Fordist society, information society, knowledge society, technological society or intelligent society (López, 2015). New conditions in the tourism sector have given rise to a proliferation of new tourism products and experiences that have fragmented the market into a broad spectrum of client types. It is vital for businesses and public administrations to identify these new classifications of clients, because they may have to revise their strategies to satisfy their wants and desires.

Research in this field began with the work of Gray (1970) and Plog (1972), which was based on traveller roles, tourist motivation, choosing a destination, lifestyles and how they relate to the trip and tourist consumption patterns, among others. In their review of the literature, Castaño, Moreno and Crego (2003) observed that the profile of each tourist was the result of combinations of variables (socio-demographic, such as age, gender or buying power, and psycho-social, such as motivations or “tourist personality”) and characteristics of their tourist behaviour (destination choice, type of transportation, preferred type of accommodation, travel experience, etc.). The most common analyses of this material combine sociodemographic and psycho-social traits of the tourist, such as gender-motivation (Watters, 1988; Bigné & Zorío, 1989; Mieczkowski, 1990; Pennington-Gray & Kerstetter, 2001; Collins & Tisdell, 2002). Much work also focuses on variables having to do with trip characteristics (Becken, Simmons &Frampton, 2003) or that combine characteristics of both travellers and trips (Bonn, Furr & Susskind, 1999). Other research uses “travel-styles” or “travel-patterns”, referring to the ways in which travellers plan and organise their stays, in order to establish motivation classifications (Smith, 1989; Basala & Klenosky, 2001). The most complex, however, are tourist profiles that combine socio-demographic, psychosocial variables, as well as trip characteristics (Moscardo et al., 2000; Bieger & Laesser, 2002). Some research has made significant contributions to segmentation in different tourism submarkets, including Ferreira (2011), Molina, Gómez and Esteban (2013), and Rodríguez and Santana (2014). Finally, we must highlight work that uses motivations as the central concept of their tourist profiles, in order to understand tourist behaviour and their purchasing decisions (Castaño, 2005; Moutinho, 1987; Esteban, 1996).

Because segmentation can be carried out in many different ways, innumerable typologies based on purchasing behaviour have been created. Concepts such as Anderson’s geosegmentation (2004) or geographic segmentation are employed, along with more traditional general objective segmentation criteria usually identified with the “client profile”. These include geographic variables (the tourist’s country or region of origin, size of their city of residence, urban density, climatology, etc.), demographic variables (age, sex, marital status, household size, family life cycle, etc.), and socioeconomic variables (income, occupation, education or training, social class, etc.). However, in these cases territory is conceived as a physical space and, therefore, merely a support or environment in which a certain segment develops, like the tourist origin.

Because of this, market segmentation procedures usually omit the territorial dimension of destinations. This is important because the majority of consumers in the same space tend to share similar attitudes, behaviours, and perceptions. Moreover, tourists are attracted to specific aspects of a destination that can be the place itself, a purpose or an event (Torruco & Ramírez, 1987). So it is possible to construct territorial buying patterns and, therefore, to classify tourist areas.

However, the territorial variable is essential for any segmentation and even micro-segmentation process, no so much for its influence on behaviour, but rather for its capacity to characterise groups (Alcaide, Calero & Hernández, 2012). Considering that tourist areas are made up of complex, heterogeneous and dynamic territorial systems with distinctive formal and functional features, it is possible to define homogenous units according to homogenous behaviour patterns. We can denominate the result “territorial segmentation of demand”.

It consists in fragmenting an urban-tourism space into small, uniform groups (consumption sub-groups), with particular characteristics that can be grouped in relation to the similar qualities, preferences, behaviours and attitudes of the tourism consumers that visit the same space. This process is a “territorialisation of tourism systems” (Vera et al., 2013), in which the characteristics and resources of the tourism area are what determine the fragmentation of the market.

Tourism areas are segmented by delimiting territorial units (zones) that share a certain level of homogeneity in several aspects.

First of all, individual units reproduce the most significant properties of a set of norms defined during the segmentation process. They are, therefore, isomorphisms that have been simplified according to repetitive patterns and consistencies in the main components and characteristics of tourism consumers. In this way, each homogenous territorial unit is the consequence of similar behaviours of certain tourism consumers.

Second, the units are the result of breaking down everything into their components (sub-systems), although without leaving out the structural relationships between them (the territorial system). This allows for a systemic and integral perspective of the tourist space, which does not overlook the universe of cause and effect or dependent relationships that occur among the significant elements. From this point of view, the units are “sub-systems” that are parts and inter-relations that structurally and functionally exist within a larger system (the tourist area, the municipality, the island, etc.) that possesses its own characteristics.

Third, they constitute models with elements (and, therefore, morphologies), structures, functions and analogous and unique evolutions; in some cases, they might even constitute “microdestinations” (Hernández et al., 2014). Therefore, they function as “categoremes” that can be used to classify the urban-tourism space. When defining a taxonomy, segmentation allows different patterns of behaviour or demand to be identified based on affiliation or homogeneity, in the sense that each unit meets the demands of the tourists. This is why it is proposed to use them as a spatial reference so that the characteristics, attitudes, behaviours, perceptions and experiences adapt to the components, the organisation and the operation of each urban-tourism space. They allow for the complexity of tourism consumer behaviour to be represented and systematised by identifying and breaking down the tourist area into zones with common properties and regularities.

Fourth, they are elements that can be used to obtain and integrate territorial information and, at the same time, they create a structure that provides spatial references to analyse tourism consumers. In this sense, identifying and classifying homogenous territorial segmentation units facilitates the operational work specific to “tourism intelligence”, which allows the pyramidal and sequential transformation of data ➔ information ➔ knowledge, when the data is used in specific processes of strategic decision making.

Fifth, they resolve the imbalance between the administrative scale (of which there are statistical data) and the functional scale (in which homogenous territorial units do not coincide with the administrative), because they introduce multiscalar processing.

Finally, they can be used to define a distinctive commercial strategy that adjusts to each segment and to homogenous consumption patterns, in order to achieve two objectives: on the one hand, to effectively satisfy the needs and desires of each segment; and, on the other, to meet business objectives by designing and applying more efficient marketing actions for each case. Therefore, they make it possible to better understand the needs and desires of new tourism consumers by customising products and services and adapting commercial offers and marketing actions to meet their tastes, identifying business opportunities, contributing to the establishment of priorities, while also facilitating the analysis of competition.

3. Geomarketing as a tool for territorial segmentation of demand

Territorial segmentation should be approached from the particular to the general, from the simple to the complex, from individual facts to generalisations, in order to later classify segments based on certain patterns and the territorial analogies that arise among tourism consumers. Geomarketing is particularly well-suited for this approach as a methodology, technique and tool. It provides information on the preferences, needs and possibilities of consumers, identifying geographic behaviour patterns, characterising the most appropriate products or services, and defining market areas based on potential profitability.

Although there are still few academic studies that have analysed geomarketing, among the most noteworthy are Cliquet (2006), Moreno (2001), Cliquet (2002), Polèse & Rubiera (2009), Galacho (1999), Corbera, González, & Vázquez (2002), Millán (2008), Latour & Le Floch (2001), Alcaide et al., (2012). The same is true of work that studies how geomarketing is applied to commercial planning (Moreno, 2002; Moreno & Prieto, 2004; Kosiak et al., 2005; Tena & Yustas, 1996; García Palomo, 2004; Calero, 2005; Baviera, 2011), health (Romero, 2008), sports (Ravenel, 2011), management and customer service (Mateo, 2012), consumer knowledge (Allo, 2014), geosocial networking (Beltrán, 2015), commercial attraction (Douard, Heitz & Cliquet, 2015; Vallejo & Márquez, 2006), ecommerce (Wild, 1999), logistics and marketing (Amago, 2000), and tourism (Peñarrubia, 2018).

There are as many definitions of geomarketing as there are authors who have analysed it. One of the first definitions was proposed by Grimmeau and Roelants (1995), who indicate that it has to do with the application of geographic concepts, methods and analysis techniques to marketing. Latour and Floch (2001) define it as a system that integrates data, processing software, statistical methods and graphic representations, designed to produce information useful for making decisions through instruments that combine digital cartography, graphics and tables. Chasco (2003) considers it to be a discipline defined by a set of techniques that can be used to analyse the socio-economic situation from a geographic perspective using cartographic instruments and spatial statistics tools. The definitions of other authors are based on a sociological-geographic view in which people who share geographic spaces tend to have similar behaviours, consumption and attitudes. Harris (2003) relates it to the analysis of socio-economic data and the behaviour of the population, with the goal of investigating geographic patterns that structure or are structured by characteristics of the settlements. Along this line, Sleight (2005) defines geomarketing as the analysis of people by where they live, suggesting a relationship between where you live and who you are.

Therefore, geomarketing is considered a central technique of decision-making processes and also as a method related to spatial analysis. In this regard, Tena and Yustas (1996) view it as a marketing management tool that improves business decisions by integrating various types of information (internal business data, demographic data, basic geographic information, etc.), thereby reducing the risk and uncertainty inherent in an aggressive and continuously changing sector. Sampaio (2005) defines it as “the management of information through a combination of spatial data and business data to support decisions within an area of the market”. Amago (2000) approaches it as an alphanumeric visualisation of the market, clients and attributes in a thematic map and in other kinds of maps to better understand the relations, tendencies and business opportunities in a geographic area. Alcaide et al. (2012) view it as an area of marketing-oriented toward a global understanding of the client, their needs and behaviours within a specific geographic environment which helps us have a more complete vision of them and to identify their needs.

These definitions reveal that territory is considered a central aspect of economic analysis, providing it a spatial dimension. In this sense, geomarketing is not just a technique that requires geolocation technology to obtain data on the location of tourists using a mobile device; it is method for spatial economic analysis.

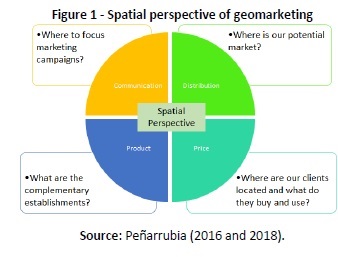

In essence, geomarketing is a discipline that analyses markets from a territorial perspective. It represents a confluence of geography and marketing, although some authors view it as a unique field (Chasco, 1997; García, 1997; Moreno, 2001; Rosa, 2001). According to Chasco (2003), the main function of geomarketing is to approach the four elements of traditional marketing (product, communication, distribution and price) from a spatial perspective (Figure 1). This helps answer several key questions asked when developing business strategies: who are our clients and who should be our clients; what are the complementary establishments: where are our clients located; what do they buy; what do they use; where is our potential market; are our distribution points located in the right places; or where should we focus our marketing campaigns. It is essential to understand the elements that make up a geomarketing system: the location and management of territorial statistical information, understanding how the geographic information system works, proficiency in statistical techniques and spatial econometrics (localization models, spatial interaction models, spatial regression), and knowledge of strategic marketing tools (Chasco, 2003).

4. Applying geomarketing in the territorial segmentation of Costa Adeje: an analysis of the possibilities of theming hotels for family tourism

Ensuring the quality of the tourist accommodation establishment model and adopting reactive adaptation processes to improve and reposition a destination when tendencies change are key strategies to promote new tourism products, attain an adequate market position, and increase the competitiveness of a tourist destination. In this regard, specialising accommodation establishments is an upgrading strategy, because it moves them up the value chain, distancing them from activities with low entrance barriers in which competitiveness depends on production costs, and repositioning toward activities in which, as mentioned, intangible factors are essential for competitiveness. The idea is for tourist accommodations to ensure the satisfaction of clients in order to obtain their loyalty (and, therefore, a sustainable market share) by offering quality products and services that surpass their expectations and continuously improving business processes to produce better products and services at lower costs. Tourists have begun to place more value on these factors and, therefore, they have become key to convincing them to return or recommend the destination to their close acquaintances. In other words, they no longer “buy” based on the rational characteristics of the activity, but rather on emotional satisfaction: “the place the tourist visits is no longer important, but rather what they do there”. This is why specialisation in family tourism could be a good strategy.

However, such clientele requires highly specialised services (accommodations, catering, transport, amenities and leisure activities) and facilities adapted to the needs of children, as they are the essence of this market segment. Children condition the choice of destination, making it necessary to develop multiple tourism offers spatially designed for them, such as theme parks, babysitting services, family routes, children’s menus, etc. Therefore, it is useful to verify if the territorial context of this destination is well suited for this market.

According to the data published by Promotur Turismo de Canarias, adapting to the needs of children (35.2%) is the second most important factor in choosing a tourist destination, after good climate and sun (92%), and before its beaches (31.4%). Surveys also revealed that the safety of the region was also a decisive factor for 12% of the families visiting the archipelago.

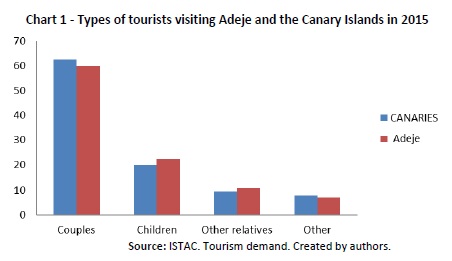

Costa Adeje is one of the most popular tourist areas in the Canaries; according to the official statistics provided by Turismo de Tenerife (Cabildo de Tenerife), it received 1,886,400 tourists and had 14,923,317 overnight stays in 2017, with 46,878 tourist bed spaces. This area is consolidating a reputation as a family tourism destination. According to ISTAC (the Canary Islands Statistical Agency), between 2015 and 2016 the segment that grew the most (26%) were tourists with their children staying in hotels, followed by tourists travelling with other relatives (8%), while couples, despite being the largest group in both years, varied only 15% (Chart 1) . Despite this tendency, it is possible that the products it offers do not adapt to this kind of tourism consumer. That is why it is important to analyse it using geomarketing.

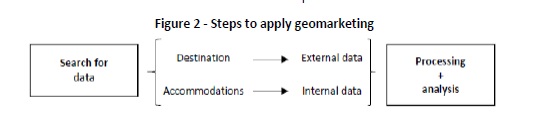

Adapting Galacho’s methodology (1999) to the territorial segmentation of a tourist area results in a sequential process that can be applied to geomarketing (Figure 2). This articulates the four basic elements of the geomarketing system: geographic information systems (GIS), databases, digital cartography of the area being studied, analysis techniques and interpretation of the results.

Tourist activity, territorial analysis of the tourism area, and knowledge about tourists are all included in any geomarketing strategy. Data, as a synonym for information, is the raw material needed to understand tourist behaviour, which is essential for making good business decisions. And this means that the processes used to generate and classify data must also be reconsidered. In this sense, “data intelligence” is extremely useful for competitiveness and sustainability in the tourism sector (Del Chiappa & Baggio, 2012). We must also consider “intelligent” tourists, who are connected and share data, and therefore more demanding because they have access to more information (Ivars, Solsona & Giner, 2016). Thus, the first task is to collect information and create the most complete database possible, and include georeferences so that it can later be spatially represented. At this point, it is common to find problems and deficiencies in statistical information systems.

The characteristics of hotels specialising in family tourism (internal data) were collected from various official sources: the Registro General de Empresas, Actividades y Establecimientos Turísticos [General Business Register, Tourist Activities and Establishments]; the Sistema de Información Turística (SIT) [Tourism Information System]; and the Turidata computer system. We also used the database created by ReinvenTUR: Observatorio de la Renovación Turística, a research group focused on renovating the tourism sector at the University of La Laguna. Using this database resolved the problem of the lack of a spatial variable in the official alphanumeric sources, providing more information beyond basic attributes, such as the postal address of each installation (street and number). The information was completed by visiting their web sites and compiling the amenities and services provided according to Hosteltur (2017): a) large, well-connected rooms for families; b) availability of certain equipment, such as cradles, strollers, highchairs, etc.; c) aquatic attractions within the hotel grounds; d) children’s menus in their cafés and restaurants; e) entertainment and educational activities for children; f) software and games; g) a hotel mascot. The majority of the hotels specialising in family tourism in Costa Adeje meet at least two of these keys (Map 1). The idea is to develop customer loyalty by making sure the client is totally satisfied with the experiences and products through excellent service, authenticity, dynamic packaging (flexible and modular tourist packages) and added value (Fayos-Solá, 1994).

Source: Council for Tourism, Culture and Sports Government of the Canary Islands, Created by authors, University of La Laguna.

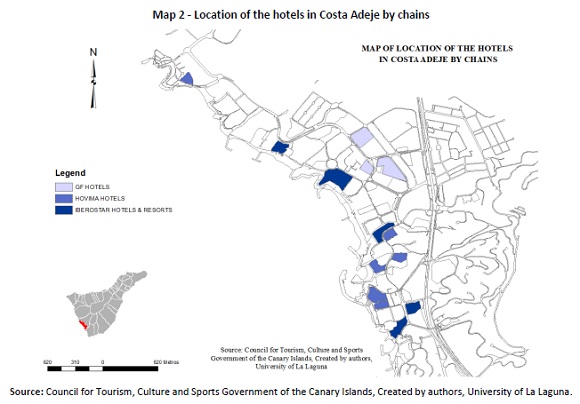

The chains that were compared in this work were Hovima Hotels, Iberostar Hotels & Resorts and GF Hoteles, with 6, 5 and 3 hotels, respectively (Map 2). They were chosen because they are the largest chains in the destination (Map 2), each with more than two hotels in Costa Adeje. Moreover, some of their hotels specialise in family tourism.

As can be seen in Map 2, hotels of the same chain are somewhat concentrated and near each other. From the perspective of the theory of industrial districts, the main reason for this geographic concentration is to obtain some advantage or positive externality that is greater than their internal capacities and makes them more competitive. In this sense, despite giving rise to greater competition for clients and downward pressure on prices, tourism companies are interested in having their hotels close to those of other chains from the same sector and specialization, because it allows them to be closer to points of interest for family tourism and to exchange the specialized knowledge that arises in the territory due to the constant interaction between similar companies.

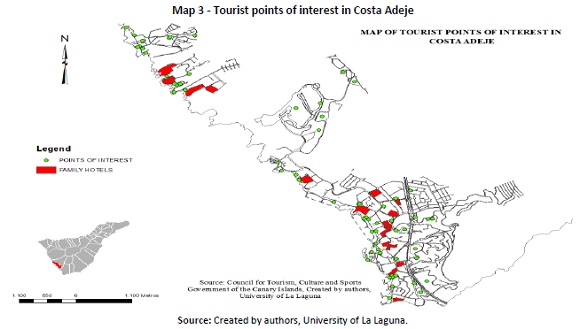

Although there is a certain tendency for these establishments to behave as resorts that provide a broad, diverse and specialised set of products and services within their grounds, the supply of infrastructures and services in the surrounding area (external data) present numerous points of interest for tourists (Map 3). However, their typology is very low, given that the majority are shopping centres, many of which are rather small.

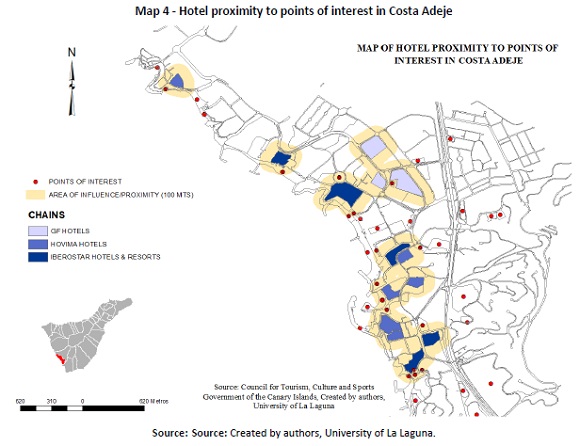

The implementation of a geographic information system (GIS) allowed us to combine alphanumeric databases with maps. This provides information related to certain factors that are key to the successful territorial segmentation of a tourist destination, specifically, the determination of the proximity of hotels to points of interest (Map 4 and Table 1).

Iberostar Hotels & Resorts has one of the most strategic geographic distributions among the hotel chains operating in Costa Adeje. The majority of its hotels are spread along the coast, with only two located closer than 100 metres apart (Boungaville Playa and Las Dalias). Having its hotels dispersed along a relatively continuous line on the coast of the municipality provides differentiated environments for each establishment, which gives clients more options to choose from in accordance with their interests in the destination. The sectors are also distinguished by the themes of the hotels and the experiences they offer. All of these factors make this chain much more competitive than others in the destination.

Although five of its hotels are more geographically concentrated, one of the greatest strengths of the Hovima Hotels chain is its proximity to the busiest tourist area, sharing that advantage with other establishments, in particular, one belonging to the Iberostar chain discussed above (Hotel Iberostar Sábila). All the hotels in the area share proximity to infrastructures and points of interest located in a radius of 100 metres.

The three establishments of the GF Hotels chain are located more than 100 metres from the points of interest; however, because these hotels offer a broad range of services and internal installations, this could be considered an advantage for the brand, because it encourages the clients to spend the majority of their time enjoying experiences provided by the hotels themselves.

5. Conclusions

As suggested by Galacho (1999), applying geomarketing strategies answers countless geographic questions that have traditionally been dealt with by employing marketing techniques. For example, it can be used to determine the market penetration index of the supply and the reach and suitability of promotions; to define how tourist accommodation establishments take advantage of their locations or nearby points of interest (for example, theme parks); to optimize business models for the territorial context; to identify the area of influence of specific projects; to determine the services, activities or themes that establishments should have; to analyse the competition or the economies of scale among nearby tourist accommodations; to characterize and determine what themes accommodations should adopt in a destination in accordance with demand; to build user profiles; channel the destination’s advertising campaigns; prioritize the execution of public infrastructures in accordance with the segmentation of the destination’s demand; identify the most suitable products for each tourist area in accordance with the typology of the demand; and to measure how the predominance of a certain type of accommodation impacts the commercial and economic activity offered in the tourist area.

Geomarketing techniques make it possible to manage tourist destinations as part of an intelligence system, as suggested by López de Ávila and Garcia (2013). This is possible because geomarketing provides procedural information that can be used to analyse and understand events in real-time in order to facilitate visitor interaction with the surrounding area and also to aid destination managers to make decisions, helping to increase efficiency and improve the quality of tourist experiences. Thus, this system models scenarios that allow for the design of suitable strategies for the territorial planning and management of tourist destinations/areas. This is because geomarketing approaches variables from two perspectives: the geographic environment and the tourist.

Furthermore, applying a geomarketing system in a tourist destination allows more detailed studies to be carried out, if the appropriate data is available, especially regarding tourist behaviour and the weaknesses and potential of the destination.

In line with intelligent business systems, applying geomarketing to the territorial segmentation of tourist areas allows for the sufficient scalar desegregation of data, generating knowledge about tourists and how they relate to the territory. This facilitates making intelligent decisions in tourist destinations.

However, we have observed that using geomarketing to analyse coastal tourism areas is determined by the typology and category of the accommodation establishments. This gives them a key role in understanding the spatial distribution of facilities, infrastructures, entertainment and services in coastal urban-tourism areas. Following the geographic perspective of the World Tourism Organization’s (2007) definition of a tourist destination, one of the essential characteristics of these coastal urban-tourism areas is the spatial concentration of tourist accommodation establishments and those facilities, infrastructures, entertainment and services, where tourists spend the night and carry out part of all of the activities during their stay.

In conclusion, the tourist accommodation variable is essential for any segmentation process and even for the microsegmentation of coastal tourism areas. It allows similar consumers to be grouped in a market from a demand perspective based on shared needs, habits or attitudes and also from the supply side, according to territorial characteristics. All of this reveals how important the territorial aspect is for public and private decision-making processes. This makes geomarketing an ideal technique for understanding tourists and how their behaviour while visiting a territory because it integrates all the variables involved in a trip: the different elements of the destination and tourist behaviour data. They can also be processed with the full territorial disaggregation, making it a suitable tool for public and private actors to make intelligent decisions for territorial planning and when defining the operational marketing strategies of a tourist company.

REFERENCES

Alcaide, J.C., Calero, R., & Hernández, R., (2012). Geomarketing: marketing territorial para vender y fidelizar más. Madrid: ESIC Editorial. [ Links ]

Anderson, V. M., (2004). Developing integrated object-oriented conception of Geomarketing as a tool for promotion of regional sustainable development: the case study of Ukraine. University of Idaho.

Aznar, J. & Nicolini, R., (2007). El sector turístico en la Comunidad Valenciana: Unos elementos de análisis de la demanda en el marco de la economía geográfica. Revista de Estudios Regionales, 79, 43"72. [ Links ]

Basala, S. L. & Klenosky, D. B., (2001). Travel Style Preferences for Visiting a Novel Destination: A Conjoint Investigation across the Novelty Familiarity Continuum. Journal of Travel Research, 40, 172-182. [ Links ]

Becken, S., Simmons, D. & Frampton, C. (2003). Energy use associated with different travel choices. Tourism Management, 24, 267-248. [ Links ]

Beltrán-Bueno, M. A., & Parra-Meroño, M. C., (2017). Perfiles turísticos en función de las motivaciones para viajar. Cuadernos de Turismo, 39, 41-65. [ Links ]

Bieger, T., y Laesser, C. (2002). Market Segmentation by Motivation: The Case of Switzerland. Journal of Travel Research, 41(1), 68-76.

Bigné, E. & Zorío, M. (1989). Marketing turístico: el proceso de toma de decisiones vacacionales. Revista de Economía y Empresa, 9(23), 91-112. [ Links ]

Bonn, M., Furr, H. L & Susskind, A. M. (1999). Predicting a Behavioral Profile for Pleasure Travelers on the Basis of Internet Use Segmentation. Journal of Travel Research, 37(4), 333-40. [ Links ]

Castaño, J.; Moreno, A., & Crego, A. (2006). Perfiles turísticos en una muestra de sujetos españoles: un modelo de segmentación empírica en función de los patrones de viaje y las características del viajero. Estudios Turísticos, 171, 57-76. [ Links ]

Castaño, J. M. (2005). Psicología social de los viajes y del turismo. Madrid: Thomson. [ Links ]

Castaño, J.M., Moreno, A., García, S., & Crego, A. (2003). Aproximación psicosocial a la motivación turística: Variables implicadas en la elección de Madrid como destino. Instituto de Estudios Turísticos, 158, 541. [ Links ]

Chasco, C. (2003). El Geomarketing y la distribución comercial. Investigación y Marketing, 79, 6-13. [ Links ]

Chasco, C., & Fernández Avilés, G. (2009). Análisis de datos espacio temporales para la economía y el Geomarketing. A Coruña: NetBiblio. [ Links ]

Cliquet, G. (2006). Geomarketing. Methods and Strategies in Spatial Marketing. Londres: Gran Bretaña: ISTE Ltd.

Collins, D., & Tisdell, C. (2002). Age-related lifecycles. Purpose variations. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(3), 801-818. [ Links ]

Del Chiappa, G., & Bregoli, I. (2012). Strategic marketing in tourism services. In R. E. Rodoula & H. Tsiotsou (eds), Strategic marketing in tourism services (pp. 51-61). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Escobar, A. & González, Y. (2011). Marketing Turístico. Madrid: Síntesis [ Links ]

Esteban, Á. (1996). El marketing turístico: la orientación de la actividad hacia el consumidor. In A. Pedreño Muñoz y V. Monfort Mir, Introducción a la economía del turismo (pp. 247-273). Madrid: Editorial Cívitas. [ Links ]

Fayos, E. (1994). Competitividad y calidad en la nueva era del turismo. Estudios Turísticos, 123, 5-10. [ Links ]

Ferreira, S. (2011). Geo-segmentación y geo-posicionamiento en el análisis de las preferencias de los turistas: La geometría al servicio del marketing. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, 20, 842-854. [ Links ]

J. Gray (1970). International Travel. International Trade. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, D.C. Heath and Co.

Grimmeau, J., & Roelants, M. (1995). Geomárketing: une presentation a travers huit ans de practique. Revue Belge de Géographie, 119, 289-306. [ Links ]

Harris, R. (2003). An introduction to mapping the 2001 Census of England and Wales. Society of cartographers Bulletin, 37, 39-42. [ Links ]

Hernández, R., Simancas, M., González, J., Rodríguez, J., García, J. I., & González, Y. (2014). Identifying micro-destinations and providing statistical information. A pilot study in the Canary Islands. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(8), 771-790. [ Links ]

Ivars, J., Solsona, F., & Giner, D. (2016). Gestión turística y tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC): El nuevo enfoque de los destinos inteligentes. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 62(2), 327-346. [ Links ]

Kotler, P., Bowen, J. T., & Makens, J. C. (2005). Marketing for hospitality and tourism. Pearson, Upper Saddle River.

Latour, P., & Le Floch, J. (2001). Géomárketing: principes, méthodes et applications. Paris: Éditions d'Organisation. [ Links ]

López, F. (2015). Barcelona, de ciudad con turismo a ciudad turística. Notas sobre un proceso complejo e inacabado. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 61(3), 483-506. [ Links ]

López, A. & Sánchez, S. (2013). Destinos turísticos inteligentes. Harvard Deusto Business Review, 224, 56-67. [ Links ]

Meng, F., Tepanon, Y., & Uysai, M. (2008). Measuring tourist satisfaction by attribute and motivation: the case of a nature-based resort. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 14(1), 41-56. [ Links ]

Mieczkowski, Z. (1990). World Trends in Touring and Recreation. Nueva York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Molina, A., Gómez, M. & Esteban, A. (2013). Segmentación de la demanda turística: un análisis aplicado a un destino de turismo cultural. Papers de turisme, 53, 1-17. [ Links ]

Moreno, A. (2001). Geomarketing con sistemas de información geográfica. Madrid, Dpto. de Geografía de la UAM-Grupo de Métodos Cuantitativos, SIG y Teledetección de la AGE. [ Links ]

Moreno, A. (2002). Delimitación y predicción del área de mercado para establecimientos de servicios a los consumidores con sistemas de información geográfica. Estudios Geográficos, 247, 279-302. [ Links ]

Moreno, A., & Prieto, M. (2004). ¿Cómo afecta la unidad espacial a la visualización y modelado del área de mercado con sistemas de información geográfica? Implicaciones para el Geomarketing. Estudios Geográficos, LXV, 257, 617-636. [ Links ]

Moscardo, G., Pearce, P., Morrison, A., Green, D., & Oteary, J.T. (2000). Developing a typology for understanding visiting friends and relatives markets. Journal of Travel Research, 38(3), 251-259. [ Links ]

Moutinho, L. (1987). Consumer Behaviour in Tourism. European Journal of Marketing, 21(10), 1-44. [ Links ]

Pennington, L. & Kerstetter, D. (2001). What do university-educated women want from their pleasure travel experiences? Journal of Travel Research, 40(1), 49-56. [ Links ]

Peñarrubia, M. P. (2016). Aproximación a la aplicación del geomarketing a la renovación de destinos turísticos de litoral. [ Links ] XIX Congreso de la Asociación Española de Expertos Científicos en Turismo.

Peñarrubia, M. P. (2018). Los datos estadísticos públicos y su uso en el conocimiento del comportamiento de los turistas en destinos inteligentes. Valencia: Universitat de València. Doctoral dissertation. [ Links ]

Plog, S. (1974). Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quaterly, 14(3), 13-16. [ Links ]

Portillo, A. (2002). Una estrecha relación entre el turismo, la geografía y el mercadeo. Geoenseñanza, 7 (1-2), 109"113. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, P., & Santana, M. (2014). Consumo turístico y desigualdad social en España. Pasos: Revista de turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 12 (1), 29-51. [ Links ]

Sleight, P. (2005). Targeting customers: how to use geodemographic and lifestyle data in your business. Henley on Thames. NTC Publications. [ Links ]

Smith, V. (1989). Host and guests: The anthropology of tourism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [ Links ]

Tena, A., & Yustas, Y. (1996). Geoestrategia: una herramienta de Gestión de Marketing. Investigación y Marketing, 52, 59-66. [ Links ]

Torruco, M., & Ramirez, M. (1987). Servicios turísticos. México: Editorial Diana. [ Links ]

Vera, J. F., López Palomeque, F., Marchena, M. J., & Antón, S. (2013). Análisis territorial del turismo y planificación de destinos turísticos. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch. [ Links ]

Vogeler, C., & Hernández, E. (2002). El Mercado Turístico: estructura, operaciones y procesos de producción. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Ramón Areces. [ Links ]

Acknowledgements

This article is based on research carried out in the project, “Analysis of urban stability as a strategy to regenerate public space in coastal tourism areas”, financed by the Caja Canarias Foundation.

Received: 25.12.2018

Revisions required: 16.05.2019

Accepted: 20.07.2019