1. Introduction

In the current competitive business environment, human resources are among the most essential assets in service-focused organisations, and bullying stands out as one of the most recognised factors affecting employees' commitment and satisfaction within an organisation (Tag-Eldeen, Barakat, & Dar, 2017). Bullying can lead to destruction, humiliation, a risk to a well-functioning work environment, and a decline in employee performance, making it a reprehensible and immoral action. Eliminating all potential sources of stress at work is crucial for maintaining outstanding work engagement and sustaining improved employee performance. Several researchers, particularly in the fields of organisational behaviour and human resource management (HRM), have focused their attention on the widespread effects of workplace bullying as part of their efforts to explain the connection between a supportive work environment, positive employee relations, and workers' productivity (Burman, 2021; Pradhan & Joshi, 2019; Gupta et al., 2017; Samnani, Singh & Ezzedeen, 2013). Workplace bullying is defined as "conditions in which a person is repeatedly and over a period of time exposed to negative acts (such as constant abuse, offensive comments or teasing, ridicule, or social exclusion) by co-workers, supervisors, or subordinates" (Devonish, 2013, p. 630).

Similarly, Srivastava and Dey (2019) and Namie (2007) have also suggested the following behaviours as forms of workplace bullying: "abusive words, insulting language, spreading gossip, rumours, harmful or offensive initiation practices, physical assault, or unlawful threats, as well as giving an excessive workload to the person, setting unrealistic timelines for the employee, assigning tasks that are beyond the employee's ability, consistently ignoring a person in their workplace, and purposely denying access to useful information." Other researchers (Livne & Gossinsky, 2018; Srivastava & Dey, 2019) have described workplace bullying as repeated ill-treatment or hostile behaviours at work, which are intended to cause physical harm, mental anguish, or public disgrace to a specific employee or employees. Although there are many ways to define workplace bullying, they all agree that it involves a pattern of negative behaviours, attitudes, and incidents that occur repeatedly for about six months and can cause severe mental distress, emotional disturbances, or physical discomfort (Burman, 2021).

Recently, researchers have noted that this type of undesirable behaviour in organisations can easily lead to several detrimental developments among affected employees, such as "health-related problems, stress, burnout, depression, and decreased job satisfaction, among others" (Gupta et al., 2017; Livne & Gossinsky, 2018). Bullying has been linked to various employee and organisational outcomes, particularly those related to performance and productivity (Sheehan, McCabe, & Garavan, 2018). Current studies have provided empirical support that workplace bullying has several adverse consequences for organisational employee performance (Devonish, 2013). Sheehan, McCabe, and Garavan (2018) confirmed that the most common results of bullying at work are poor job performance, more absences, greater intentions to quit, and lower job satisfaction. The literature also supports the claim that bullying can demotivate employees who were initially motivated to the point where it significantly hinders their performance.

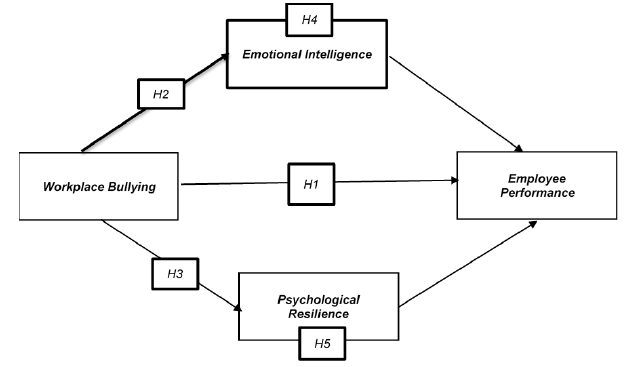

Some researchers have investigated the link between bullying and employee performance, and they discovered that performance is connected to employees' outcomes, such as accomplishments and achievements in the workplace (Bentley et al., 2012; Pradhan & Joshi, 2019). Gómez-Trinidad, Chimpén-López, Rodrguez-Santos, Moral, and Rodrguez-Mansilla's (2021) study on the performance of caregivers of dementia patients in Spain confirmed that resilience and emotional intelligence are positively related to good job performance. However, studies on the connection between bullying and employee performance within the hospitality industry are scarce, and they have not thoroughly explored whether workplace bullying directly influences employee performance or indirectly affects it through specific psychological mechanisms such as resilience and emotional intelligence (Bentley et al., 2012; Anasori, Bayighomog, & Tanova, 2020). Due to this knowledge gap, the current study aims to fill it by providing new insights into the observable evidence of psychological resilience and emotional intelligence as key mediators that can significantly mitigate the adverse effects of bullying on employee performance in various workplaces.

2. Literature review

2.1 Conceptual review and hypotheses development

2.1.1 Workplace bullying

Bullying is conceptualised as repeated intentional or wanton harm to individuals with lesser strength, mostly manifested through physical, psychological, social, or emotional outbursts (Bunnett, 2021). According to research, bullying can be classified as either direct or indirect, depending on the nature of the unproductive behaviours used to mistreat weaker or more vulnerable individuals. Direct bullying involves overt behaviour or aggressive physical acts, while indirect bullying occurs in the form of covert acts (Wolke, Woods, Stanford & Schulz, 2001). Previous research (Bunnett, 2021; Devonish, 2013; Solberg and Olweus, 2003) has found that bullying occurs when such incidents happen at least twice or three times a month.

2.2.2 Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence (EI) is an individual's ability to monitor oneself and others, enabling them to make discerning decisions by using information to manage their emotions (Abraham, 2004). Much of the literature on EI and employee performance in organisations suggests that it directly influences superior performance among employees, which is considered encouraging because an organisation's competitive advantage is closely tied to the performance of its employees (Wolff et al., 2002; Wong & Law, 2002). However, according to Abraham (2004), it is not just emotional intelligence as a whole that affects performance, but specific emotional skills such as self-control, resilience, and social skills that play a significant role. EI is seen as a crucial factor contributing to better workplace performance, and a deeper understanding of its specific components can help organisations foster a more productive and emotionally intelligent workforce.

2.1.3 Psychological resilience

Resilience is considered capable of safeguarding an individual's positive psychological functioning against stressors. This construct has been identified as an interplay between an employee and their immediate environment. According to Garcia-Izquierdo et al. (2019), resilience is a psychological construct reflecting an individual's potential to endure, recover, and emerge stronger in adversity. After facing challenging life experiences or encounters, some individuals can recover faster than others and can be a source of strength. This suggests that resilient individuals may be able to maintain their internal psycho-wellbeing by mitigating the negative consequences of difficulties. Abraham (2004) views resilience as the basis of self-control that regulates aggressive reactions when employees are confronted with workplace challenges by prioritising organisational outcomes over individual needs. Similarly, resilience, self-control, and integrity have been identified as essential skills that can significantly influence performance. Resilience plays a crucial role in promoting an individual's ability to cope with setbacks and maintain psychological well-being and health, making it essential to consider in understanding employee performance and overall workplace dynamics (Garcia-Izquierdo et al., 2019). Yilmaz and Konaklioglu (2022) state that employees' well-being has a significant direct or indirect effect on individual and organisational performance.

2.1.4 Employee performance

Employee performance can be identified as the level of task or role performance of an employee and, technically, refers to the quantity and quality of what an employee does or contributes to the overall output (Unguren & Arslam, 2021). It also involves the effort and time that an employee dedicates to their job (Aribaba et al., 2019; Robert, 2018). Generally, employees perform better when the work environment is positive and perceived to be free from any form of physical or psychological discomfort. This employee's well-being has a significant direct or indirect effect on individual and organisational performance (Yilmaz & Konaklioglu, 2022). Numerous studies link workplace bullying to lower job performance (Jackson et al., 2002; Maidaniuc-Chirila, 2015). A meta-analysis study discovered that bullying is associated with poorer job performance when it occurs frequently (Bowling & Beehr, 2006).

2.1.5 Workplace bullying (WB) and employee performance

The effects of bullying on workers' health and productivity have been the subject of multiple studies that deserve recognition. For instance, Arifin, Nirwanto, & Manan (2019) found that perceived bullying, particularly "professional understating," predicts a decrease in work engagement and work performance among academics. These authors further explained that a decline in performance may precede a diminution in engagement. Hence, this reduction in work engagement is believed to be responsible for the associated decline in performance. Tag-Eldeen, Barakat, and Dar (2017) investigated the magnitude of bullying's influence on organisational outcomes among five-star hotel workers in Egypt and reported a significant positive association between workplace bullying, employees' morale, and turnover intentions. However, the discovery further revealed an insignificant link between workplace bullying and employee performance. Srivastava and Dey (2019) found that workplace bullying reports were connected with higher levels of job burnout but lower levels of resilience. The results show the provisional indirect effect of workplace bullying on job burnout through resilience and emotional intelligence (EI). Hayat and Afshari (2020) state that employee burnout is a major cause of low morale and productivity at work, affecting an employee's well-being. Furthermore, workplace bullying has been linked to a higher likelihood of an employee leaving (Srivastava & Agarwal, 2020). On the other hand, research conducted by Nazim, Ihsan, and Ahmad (2021) among academics at Pakistani universities indicated that workplace bullying had a strong negative link with job satisfaction and performance. Chia and Kee (2018) also investigated how workplace bullying affects salespeople's task performance and organisational stress in Malaysia's retail sector. Hence, their findings advocate that workplace bullying is a major factor affecting occupational stress.

Using the latent factor technique, Park and Ono (2017) studied data from Korean workers and found that workplace bullying significantly decreased workers' engagement at work and exacerbated health problems due to a high level of perceived job insecurity. Anasori, Bayighomog, and Tanova (2020) showed that bullying is a strong indicator for measuring burnout, while resilience and psychological distress partially moderated the connection between workplace bullying and burnout in the hospitality industry.

According to the research conducted so far, workplace bullying has several detrimental effects on employees, especially their work performance. However, despite the large number of studies and important findings reported on the issues of workplace bullying and employee performance in different organisational settings, it has been noted, to the best of our knowledge, that there is a dearth of empirical literature concerning the influence of workplace bullying on employee performance within the hotel sector of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Therefore, this study investigates the direct influence of workplace bullying on hotel employees' performance. Thus, we hypothesise that:

H1: Workplace bullying significantly influences employees' performance.

2.1.6 Workplace bullying, employee performance, and emotional intelligence

Researchers have linked emotional intelligence to various life issues. For instance, Andrei et al. (2016) reported EI as a significant predictor of subjective well-being and job performance (O'Boyle et al., 2011), social support (Goldenberg et al., 2006), intelligence quotient (Webb et al., 2013), and health (Martins et al., 2010; Mikolajczak et al., 2015). However, a quantitative causality survey study among 148 employees in a wood processing industry revealed that absorption fully mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and employee performance (Arifin et al., 2019). Tabassum et al. (2021) equally found that workplace bullying has a significant negative impact on employees' success. The finding also showed that a person's sense of self-efficacy fully mediated the relationship between being bullied at work and being good at their job.

Again, a qualitative study on workplace bullying and intention to leave by Srivastava and Agarwal (2020) found that emotional exhaustion mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and intention to leave among hotel employees in India. In a related study, Arifin et al. (2019) investigated the impact of employees' engagement and job satisfaction on the nexus between bullying in the workplace and job performance. The findings revealed that employee engagement fully mediated the relationship between bullying and job performance, while job satisfaction partially mediated the association between bullying and job performance. Even though several studies have investigated the indirect effect of workplace bullying on employees, there is still a dire need to recognise the role of emotional intelligence in the bullying-performance relationship. Thus, we hypothesise that:

H2: Workplace bullying positively influences emotional intelligence.

H4: Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between workplace bullying and employee performance.

2.1.7 Workplace bullying, psychological resilience, and employee performance

Various aspects of bullying, such as its causes and effects on workers and businesses, have been studied in depth by researchers in recent years (Maidaniuc-Chirilă, 2015; Samnani, 2012). Several studies have found links between workplace bullying and employee performance and other critical psychological mechanisms such as psychological resilience, emotional intelligence, stress, and life satisfaction.

Maidaniuc-Chirilă (2015) investigated the role of resilience in mediating workplace bullying and employee strain among 88 Romanian workers using a cross-sectional survey design. The findings indicated that resilience acted as a mediator between workplace bullying and physical strain, and that the strength of the direct association between the two was mitigated in the presence of resilience. Based on these results, it seems that workers who are naturally more resilient may feel less physical stress when they are bullied at work.

García-Izquierdo, Meseguer-de-Pedro, Soler-Sánchez & Fernández-Valera (2019) found that a high experience of workplace bullying results in poorer health, claiming that resilience significantly mediates the workplace bullying-employees' health relationship. Yu et al. (2016) discovered that high resilience is linked to less maladjustment, while low resilience has been associated with incapacitated psychological functioning. Furthermore, a study by Chen et al. (2018) found a negative link between young adults' resilience and how stressed they feel.

Similarly, Park and Ono (2017) discovered that health-related job insecurity mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and disengagement. An additional rationale demonstrates that the job insecurity variable is necessary for explaining the connection between workplace bullying and engagement. Job insecurity is discovered as an additional underlying mechanism explaining why bullying promotes health problems among organisational employees, given the partial mediating influence of health problems.

Burman (2021) also confirmed that resilience and psychological health equally mediate the bullying-employee turnover intention. Furthermore, Peng et al. (2021) researched 493 clinical nurses in China, and the results showed that resilience mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and professional quality of life. It was also reported that workplace bullying had a direct but negative effect on nurses' professional quality of life. Thus, Peng et al. (2021) stated that resilience helps professionals deal with stress at work as a protective factor.

Hayat and Afshari (2020) concurred, arguing that bullying indirectly has a negative impact on workers' well-being due to the humiliation it inflicts on victims. Once more, the link between bullying and satisfaction was found to be mediated by teachers. So, these data imply that resilience mitigates the obliquely detrimental impacts of bullying on workers' morale and productivity.

Some authors state that resilience acts as a protective shield, enabling individuals to endure the challenges of hardships and stress (Anasori, Bayighomog & Tanova, 2020). Resilience is a form of psychological capital that indicates one's ability to bounce back from adversity. In a nutshell, the level of employee outcomes in the face of a workplace bullying experience is a function of one's coping ability (Anasori et al., 2020).

Despite the large volume of empirical studies that have investigated the mediating role of psychological resilience on workplace bullying, its indirect effect on the nexus between bullying and employee performance has yet to be sufficiently explored. In light of this, the researchers make the following hypotheses about the relationships depicted in Figure 1:

H3: Workplace bullying positively influences psychological resilience.

H5: Psychological resilience mediates the relationship between workplace bullying and employee performance.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study area and participants

This study focused on the hospitality and hotel industry in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). The TRNC is an island with corporate views comparable to other emerging countries, especially small states. Only Turkey has granted it diplomatic recognition, and it relies on Turkey for economic, political, and military support. The Turkish Republic of North Cyprus districts are Lefke, Güzelyurt, Gazimausa, Girne, Lefkoşa, and İskele (TRNC Census, 2006; 2011).

The study participants comprised twenty 5-star and one hundred and twenty-seven 4-star hotels, selected from a total of four hundred and eighty-six hotels within the Northern Cyprus region of Turkey. The selection of 5-star and 4-star hotels was based on their recognised number of comfortable hotels, as affirmed by the Ministry of Tourism and Environment (2018) and the North Cyprus Hoteliers' Association, as mentioned by Ibrahim (2021).

A multi-stage sampling technique was adopted. In the first stage, three districts (Gazimausa, Girne, and Lefkoşa) were selected out of six districts on the island. In the second stage, twenty hotels were randomly selected, including both 5-star and 4-star hotels, from each district selected in stage one. These hotels were considered the most preferred hospitable institutions, offering unique amenities and upscale quality service, providing extraordinary comfort and flawless guest services. In the third stage, ten (10) employees were randomly selected from each hotel, resulting in a sample size of six hundred for the study.

3.2 Measures

A well-structured survey was adapted and modified to collect data using the existing research as a model. Workplace bullying (WB) was operationalised using a 12-item survey containing unfavourable actions taken by employees at their workplaces over at least six months. This survey comprised four dimensions, each with three statements (Einarsen et al., 2009; Escartín et al., 2017; Nam et al., 2010; Olaleye et al., 2021). Respondents rated the statements on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (daily).

Emotional intelligence was assessed based on Chin-Shan and Szu-Yu's (2016) research. Psychological resilience was measured using six items from the "State-Trait Assessment of Resilience Scale" (STARS), as indicated by Lock, Rees, and Heritage's study (2020). For measuring employees' performance, a seven-item scale called "in-role or task-related behaviours (IRB)," created by Williams and Anderson (1991) and adopted by Devonish (2013), was used. All items in the study were adapted and modified to be rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), except for workplace bullying, which used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = none; 2 = less than a month; 3 = monthly; 4 = weekly; and 5 = daily).

3.3 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample population in terms of frequency and percentage. Pearson's correlation was employed to examine the relationships between variables. Correlation analysis was used to explore how the variables interact, and the suggested structural model was tested for multi-collinearity and psychometric validity before being confirmed using "Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling" (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM makes fewer assumptions than CB-SEM and breaks the model into smaller parts to explain as much variation in the dependent constructs as possible (Hair et al., 2012). Additionally, the bootstrapping technique was used to investigate the significance of the path coefficients.

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Findings

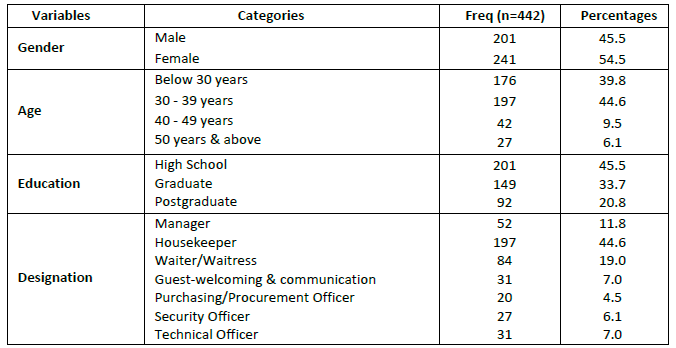

Out of the 600 surveys that were sent out between February and May 2022, only 442 were used. This is a response rate of 73.7%. Table 1 gave a report on descriptive statistics exploring respondents' appropriateness for the study. The sample comprises four hundred and forty-two (442) workers from TRNC hotels. In this sample, there were 54.5% females and 45.5% males. The average age of respondents was 34%, with the majority falling within the range of 30-39 years, while the least age fell within the 50 years and above range. Respondents' highest educational qualification profile depicts 45.5% possessing a high school degree, followed by a bachelor's degree (33.7%), while the least response (20.8%) accounted for postgraduate studies. Meanwhile, the designation of the interviewed respondents showed that the majority (44.6%) were housekeepers, followed by waiters and waitresses (19%), while an equal proportion (7%) came from the technical, guest-welcoming, and communication departments, and the least was from the purchasing and procurement unit of the hotels. Hence, the demographic profile is presented below.

4.2 Test of Hypotheses

4.2.1 Measurement Models

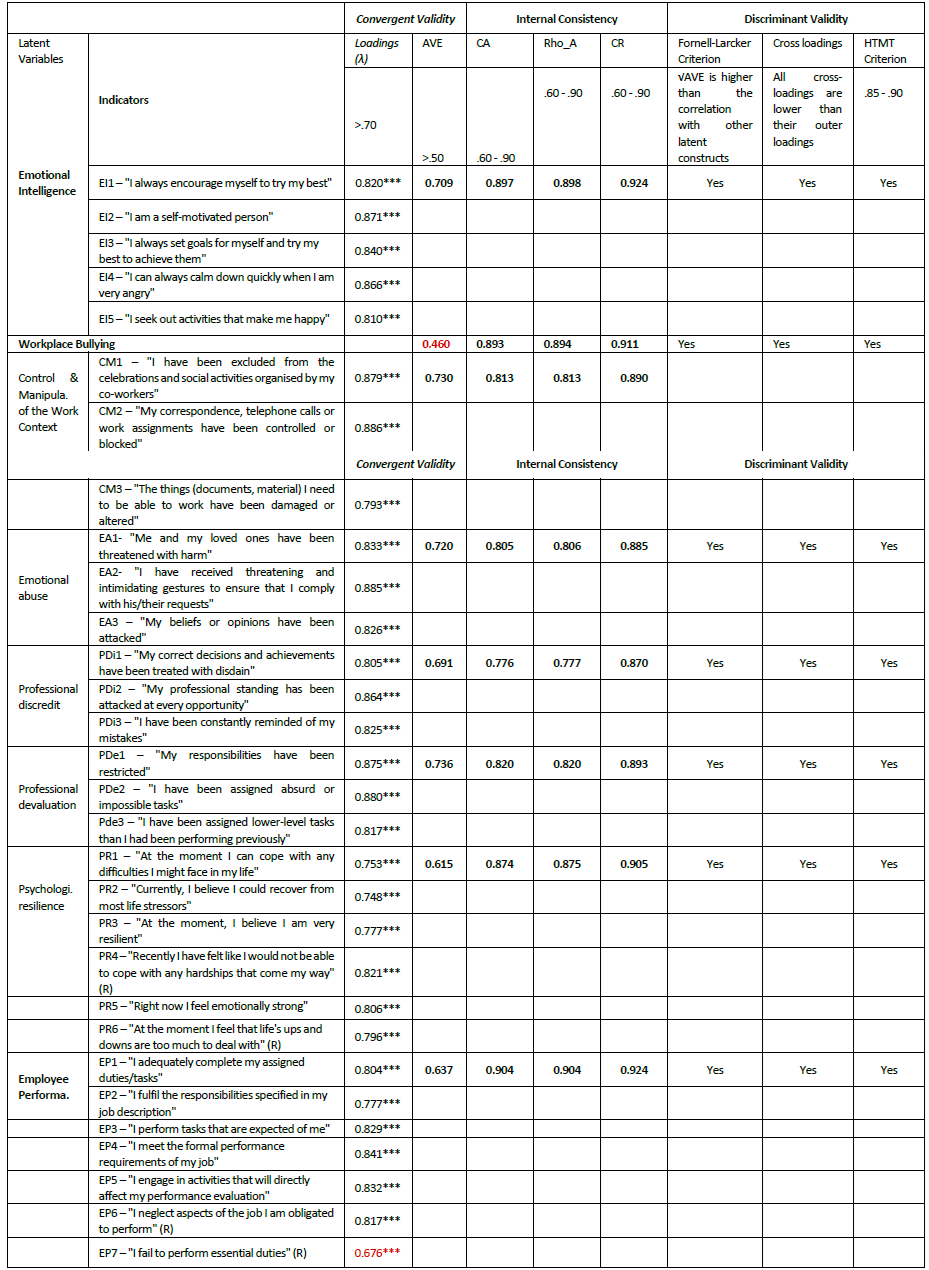

The measurement model's findings are summarised in Table 2, including using "Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)" to assess the psychometric features of the variables; emotional intelligence, workplace bullying, psychological resilience and employee and performance. All latent constructs are psychometrically tested to evaluate the measurement model. The test comprises "the outer loadings, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), Cronbach's alpha (CA), rho A values, and the convergent validity of items related to their constructs" (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 2 Results summary of the measurement model

Source: Author's computation. Note: *** = p < 0.01., Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), Cronbach's alpha (CA), Heterotrait-Monotrait Criterion (HTMT)

Meanwhile, all measures "Cronbach's alpha, Composite Reliability, and rho_A" values exceeded the 0.7 thresholds, confirming the measurement model's convergent validity (Dijkstra & Henseler 2015). Attributed to the fact that all AVEs are more than the threshold (0.5), except for workplace bullying (AVE = 0.460), but since the sister indicator, composite reliability (CR) is greater than 0.6 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). "Convergent validity" is supported by the low AVE value of modified scales (Iyer, 2017; Olaleye et al., 2022; 2021). Hence, the overall measurement indicates an acceptable fit and a strong predictive power.

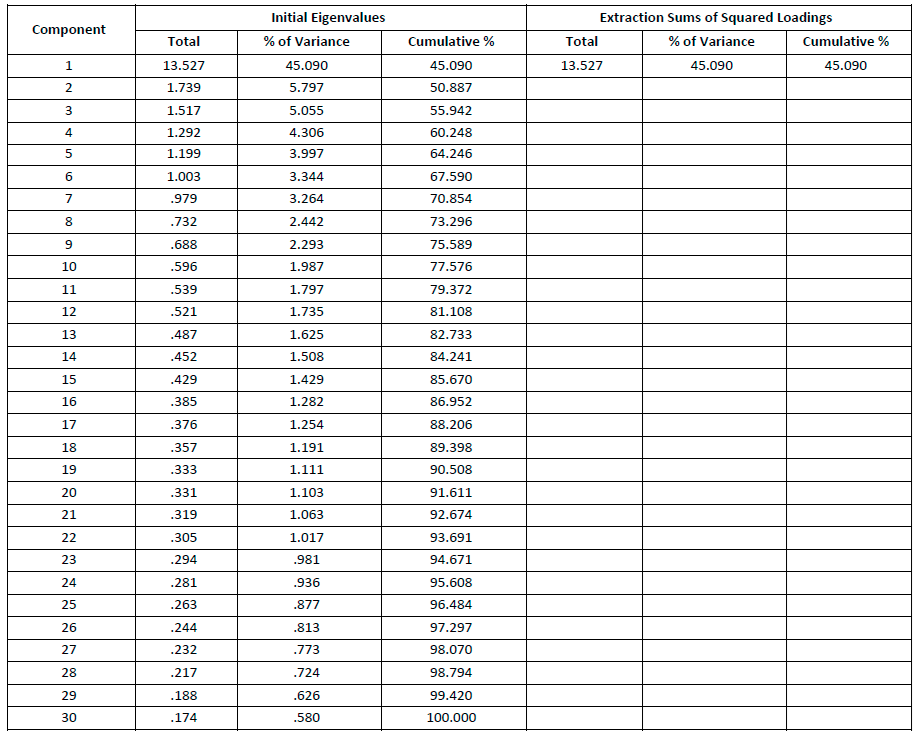

4.2.2 Common Method Bias (CMB)

As a way to deal with "common method bias" (CMB), we used Harman's single-factor test to find the most important factor that caused the differences between the variables in our study. So, changes in a single component can be used to figure out if a technique is biased (Podsakoff et al., 2003). This research only accounts for 45.09% of the variance, which is below 50% and indicates that CMV is not a major problem (see Table 3).

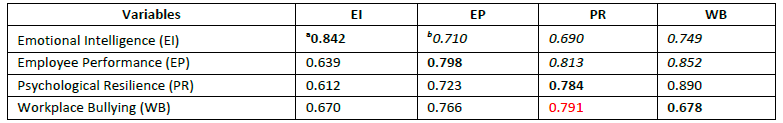

4.3 Discriminant Validity

According to the Fornell-Larcker (1981) criterion, "the square root of AVE for each latent variable is greater than the inter-construct correlation for each construct", except for psychological resilience, which has an AVE square root less than its correlation value. Also, the Fornell-Larcker (1981) criterion was criticised, which led to the creation of a different method called the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) correlation ratio, which became more popular than the "Fornell and Larcker approach" (Henseler et al., 2015). As affirmed by Kline (2005), the HTMT values directly above the AVEs' square roots indicate a prevalence of discriminant validity among the model constructs since they fell below the limits of 0.90 (see Table 4).

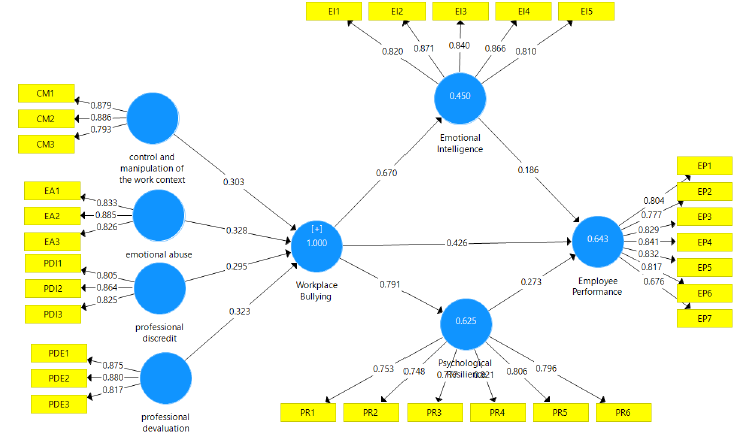

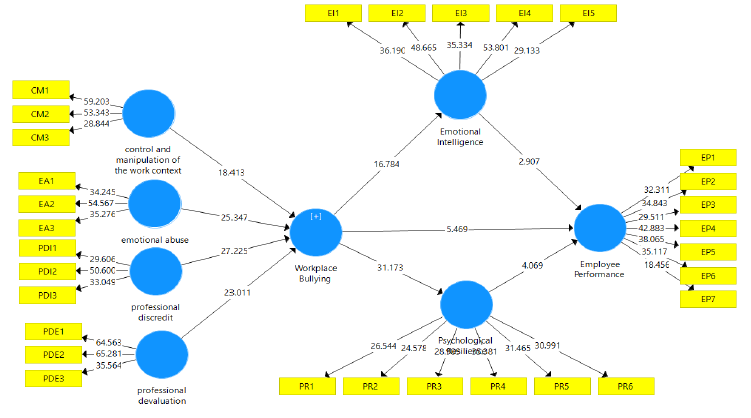

4.4 Structural Model

The structural model was also assessed in addition to the measurement model, using the path coefficient and t-statistic diagrammatically represented in Figures 2 and 3. To estimate the path coefficient and the R-squared, as well as other statistics like the t-statistic, the P-value, and the f-statistic, the structural model is frequently used to evaluate the instrument's causal constructs, as depicted in Table 5 and Figure 2.

4.4.1 Direct and indirect effects

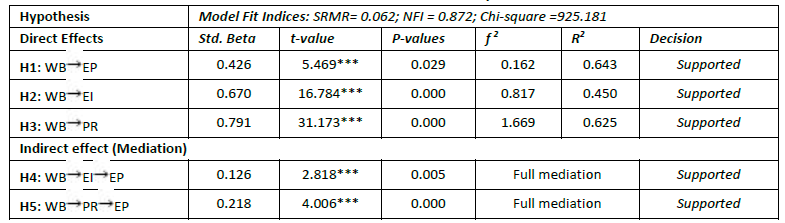

Researchers found that workplace bullying has a favourable impact on employee performance (H1: β = 0.426, t = 5.469, p 0.05), emotional intelligence (H2: β = 0.670, t = 16.784, p 0.05), and psychological resilience (H3: β = 0.791, t = 31.173, p 0.05). Emotional intelligence and psychological resilience have a substantial indirect effect on workplace bullying and employee performance (H4: β = 0.126, t = 2.818, p 0.05; H5: β = 0.218, t = 4.006, p 0.05). All theorised direct and indirect paths are supported by this analysis, as presented in Table 5.

Sullivan and Feinn (2012) say that the substantive significance (F2), the beta coefficient, the statistical significance (p-value), and the variance explained (R2) should all be included in the report. Using Cohen's (1988) thresholds of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, they recommend classifying impacts as small, moderate, and large. Except for the WB EP path, all reported effect sizes were large, exceeding the 0.35 criterion. While the model fit assessment is not strictly necessary to report in PLS-SEM, it was performed here because the NFI (0.872) was near 1, and the SRMR value (0.062) was below the threshold of 0.08 (Hair Jr. et al., 2017) at which model fit is established. As a result, we know the model employed to investigate the underlying concept is accurate, as shown in Figure 3.

EP path, all reported effect sizes were large, exceeding the 0.35 criterion. While the model fit assessment is not strictly necessary to report in PLS-SEM, it was performed here because the NFI (0.872) was near 1, and the SRMR value (0.062) was below the threshold of 0.08 (Hair Jr. et al., 2017) at which model fit is established. As a result, we know the model employed to investigate the underlying concept is accurate, as shown in Figure 3.

Table 5 Results of the Path Analysis

Source: Author's Computation, 2022. Note:"***p < 0.05 (based on two-tailed test). **Significant at the p < 0.10 level (two-tailed)"

5. Discussion and conclusion

The present study remains highly relevant as it explores various connections between workplace bullying and employee performance while understanding the mediating roles of emotional intelligence and psychological resilience in managing bullying to prevent low employee productivity.

Previous researchers have found a link between workplace bullying and employee performance. Studies by Majeed and Naseer (2019), Samnani et al. (2013), and Sidle (2009) have supported a positive relationship between the two variables. However, Pradhan and Joshi (2019) discovered that workplace bullying can also improve employee performance. On the other hand, the results of hypothesis one contradict several studies that have asserted an adverse effect of bullying on employee performance (Ashraf & Khan, 2014; Devonish, 2013; Nwaneri et al., 2013; Olaleye et al., 2021). According to Lutgen-Sandvik et al. (2007), as cited by Samnani et al. (2013), "a typology of target attributions about workplace bullying," developmental stage bullying involves persistent criticism targeting individuals with high levels of optimism, which can result in improved work efficiency. The positive association between workplace bullying and employee performance is likely when bullying motives include self-gain by superiors, using bullying to deceive subordinates into working excessive hours by promising promotions or using fear and intimidation. This occurs when the target perceives the conduct as work-driven, person-driven, and positive (Liefooghe & Davey, 2001; Samnani et al., 2013).

The outcomes of this study established that bullying assists hotel employees in building high emotional intelligence. Consequently, the results of hypothesis two confirmed a positive and significant relationship between workplace bullying and emotional intelligence, implying that highly emotionally intelligent employees were less likely to experience bullying behaviours in their workplace. According to existing literature, the bullied employee may experience either relief or increased stress, depending on how they interpret the bully's actions (Brotheridge & Lee, 2010). The results are consistent with prior research indicating that workplace bullying, if adequately managed, can strengthen an employee's emotional intelligence and positively impact their performance. Hence, in this context, bullying often triggers positive emotions towards work (Bilgin & Taş, 2018; Ismail et al., 2018). The findings supported the third hypothesis on the connection between workplace bullying and psychological resilience. There is a significant link here, and the result agrees with most prior studies that addressed this connection (Gautam & Sharma, 2017).

Hypothesis four focuses on the influence of emotional intelligence (EI) on employee performance in the context of workplace bullies. The finding that EI significantly and positively mediates the relationship between workplace bullying and employee performance does not come as a surprise because it corroborates earlier empirical studies (Sheehan & Jordan, 2000). Managers and HR professionals strive to boost job performance, and EI is considered a crucial organisational success factor. Using emotional intelligence to cope with workplace bullying may lessen the negative consequences on employee job performance. Research suggests that managers bully employees because they may lack the ability to react emotionally appropriately (Sheehan & Jordan, 2000), while other studies have focused on bullying due to a victim's weak EI (Mathisen et al., 2011). The results of hypothesis five confirmed that psychological resilience is a positive and significant mediator of the relationship between workplace bullying and employee performance. Partial mediation indicates that workplace bullying still directly affects employee performance, even when considering other factors. Workplace bullying, as a source of stress, continues to impact how employees behave. This suggests that their emotional state can, directly and indirectly, influence their performance. Hutchinson and Hurley (2001) highlighted that workplace bullying, directly and indirectly, affects the victim or target, leading to consequences such as depression, anxiety, job dissatisfaction, negative or hostile behaviour, and unproductive work culture. Emotional intelligence and psychological resilience both play crucial roles in the relationship between workplace bullying and job performance. As one of the first studies to examine this connection, it delves into how emotional intelligence and psychological resilience impact employees' job performance.

6. Theoretical and managerial implications

This startling outcome may be explained by socio-cultural theory, as Monks et al. (2009) suggested, which proposes that bullying may be rooted in authoritarian or hierarchical organisational cultures. In hotels with such cultures, emotional abuse, control, and manipulation of the work context may be perceived as appropriate. Employees enduring verbal abuse and work manipulations may not recognise them as bullying but rather view them as cultural norms. Consequently, since they don't perceive themselves as bullied, their job performance is not significantly affected.

Hotels and other businesses can strengthen their anti-bullying policies and procedures to address the more subtle forms of bullying that occur outside of work. The results of this study have significant implications for the hospitality industry. For example, hotel managers can use this information to prevent and address bullying in the workplace, thus enhancing the quality of service provided to guests by improving employees' emotional intelligence and enhancing their psychological resilience. Hotel management should prioritise creating a comfortable and secure environment for all workers by actively preventing any form of bullying. Finally, managers can support employees in enhancing their emotional intelligence and resilience to better cope with bullying practices that may hinder their work performance.

7. Limitations and suggestions for future research

Despite the valuable contributions of the present study, it is essential to acknowledge that a relatively small number of hotel employees in North Cyprus were sampled. The cultural component and the limited data from the few hotels may have implications for the generalizability of the findings, thus prompting the need for replications in other industries, countries, or continents to strengthen the study's external validity.

Furthermore, the current research solely focused on the mediating role of emotional intelligence (EI) and psychological resilience (PR). Future studies could expand their investigation by considering their interaction and treating them as moderators, enhancing the study's scope and providing a more comprehensive understanding of their combined effects.

Regarding emotional intelligence measurement, while the study utilised the "use of emotion" dimension, future research can explore other dimensions of emotional intelligence to capture a more comprehensive view of its impact on workplace dynamics and employee outcomes.

Additionally, further studies can delve into intriguing questions such as: How does emotional intelligence influence resilience? How can hotel managers effectively manage bullying to avoid negative employee productivity and performance impacts? Addressing these questions would benefit the global hospitality industry significantly and provide practical insights for managers and policymakers.

Lastly, instead of a cross-sectional design, future studies may consider adopting a longitudinal approach to study the causal effects among variables over an extended period of time. This would allow for a deeper understanding of the relationships and how they evolve over time, providing more robust evidence for managerial interventions and organisational policies.