1. Introduction

Among many other reasons, the increased interest in, and the importance of, sustainability have led to the growth of the sharing economy (Albinsson & Perera, 2012; Rojanakit et al., 2022). The idea behind the sharing economy is simple: individuals can obtain, share, or give access to goods and services coordinated through online services (Pugliese, 2016). This concept is successful because, on the supply side, people can make money by providing rentals of, for example, under-utilised rooms or vehicles (Zervas et al., 2014). Consumers benefit from the sharing economy by renting goods or services at a lower cost than renting through a traditional provider. See Ince and Hall (2017) for a constructive critique of the concept of sharing as a practice, politic and possibility in local and global economies.

One of the most successful businesses in the sharing economy is Airbnb (Adamiak, 2019). In this online marketplace, hosts list their spare rooms, apartments, or houses as accommodations for Airbnb guests, establishing their own prices (Zervas et al., 2014). Guests can search for accommodation based on destinations, travel dates, and party size. The host provides information about the accommodation, mainly consisting of a general description of the space, photographs, a list of services, and the host's profile (Guttentag, 2015). When a reservation is made, payments can be made through the Airbnb website, through which Airbnb earns its revenue by charging a fee.

It is germane that the unknown Airbnb guest must have trust both in the online platform and the unknown Airbnb host. After all, booking an accommodation via Airbnb entails more risks compared to booking via, for example, a travel agency because of the individual-to-individual agreement, which a third party does not vet. People tend to be careful when accepting a stranger in their home or when booking a stranger's home (Guttentag, 2015). Without mutual trust between the guest and the host, no access can be given to the accommodation, and no decision on the accommodation can ensue (Ter Huurne et al., 2017; Räisänen et al., 2021). Therefore, the Airbnb host creates a profile in which personal information is disclosed. Recently, Teubner (2022) found that self-descriptions compensate the trust loss induced by omitting photos in the Airbnb offer. Specifically, the degree of self-disclosure (or explicitness) by the Airbnb host influences the trust perception of the Airbnb guest and, subsequently, the intended behaviour to book the accommodation. In addition to trust as a personal trait of the Airbnb guest, a culturally specific disposition to avoid uncertainty might also play a role. Several studies have found that such cultural differences influence consumers' online trust and online behaviour in the sharing economy (Sahi et al., 2016; Tran et al., 2022).

The current study focuses on users of the Airbnb platform from China and the Netherlands in order to examine potential cultural differences when booking on Airbnb. The research question is as follows: What is the relative effect of the Airbnb host's self-disclosure on trust and booking intention, respectively, differentiated by cultural background?

2. Hypothesis forming

2.1 Self-disclosure and booking intention

Self-disclosure in the form of a personal profile is often a prerequisite for successfully acting in online marketplaces such as Airbnb because self-disclosure can positively affect the relationship between parties (Joinson et al., 2010; Moon et al., 2019). Information about the self, i.e., the Airbnb host, is expressed to others, i.e., the Airbnb guest. Self-disclosure varies in the amount of information revealed and its depth, which refers to the level of intimacy of the disclosed information (Taddei & Contena, 2013). Language expressions can include personal exposure, such as personal information, experiences, thoughts, and feelings (Barak & Gluck-Ofri, 2007). Airbnb hosts tend to share their origin or residence, their work, and their education. Statements about personality or values are less commonly used in this online marketplace (Ma et al., 2017).

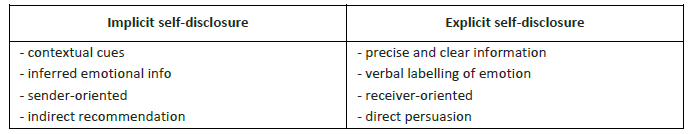

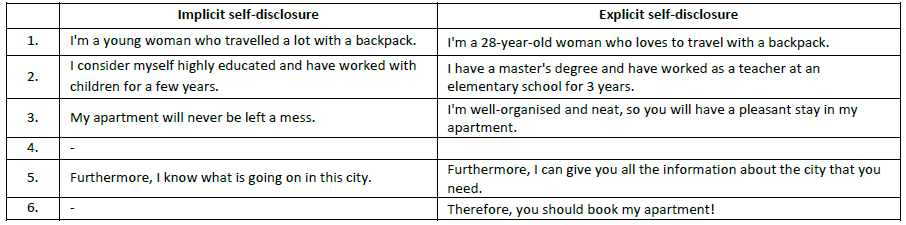

Two different types of information can be disclosed in online profiles: explicit and implicit (Jarrah, 2016; Liang et al., 2019; Yus, 1999). First, explicit information is presented in the most influential and efficient way feasible. Explicit language expressions are precisely and clearly expressed so that (almost) no room for other interpretations is left. It can be processed in relatively less time, requiring less effort and resources than implicit language expressions. Second, implicit information requires contextual cues. Therefore, the associated implicit language expressions can be more likely interpreted in multiple ways. For example, the use of "old" to describe age could be interpreted differently by people with widely different ages because their understanding of "old" will probably differ. Explicit and implicit information types differ in the way emotion is expressed. Explicit information involves references to emotions through verbal emotion labels (e.g., "I am angry"). In contrast, implicit information includes the emotional style of the message, as can be inferred from the degree of personal involvement, language use, etc. (Derks et al., 2008). Third, explicit information is more receiver-oriented, i.e., utilising language directly addressing another person ("you") or a recommendation that persuades the receiver to perform a specific task (e.g., "You should book this accommodation!"). In contrast, implicit information is often more sender-oriented. This means that the writer is the text's main focus, although the writer mostly does not use the "I" statement (Savicki & Kelley, 2000). Finally, because the addressee is spoken to with "you," explicit language is often seen as more persuasive. Implicit language is often considered pleasant and polite. Since no direct recommendations exist, the customer can voluntarily decide whether to perform the intended behaviour. Table 1 summarises these typical differences between implicit and explicit self-disclosure in Airbnb profiles.

On Airbnb, the host must decide how to communicate a certain message in her/his text-based personal description, whereas the Airbnb guest has to decide how to interpret the provided information. The type of disclosed information and associated language use influences the guest's attitude and helps the guest evaluate the intended behavioural outcome: booking the specific Airbnb accommodation. Hence, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 1: A profile presentation with high self-disclosure yields higher booking intentions than one with low self-disclosure.

2.2 Self-disclosure and trust

Ter Huurne et al. (2017) systematically reviewed extant studies on factors that determine trust in the shared economy. On the basis of consumer behaviour studies, Broeder (2020) identified three types of trust, namely (1) trustworthiness, (2) initial trust, and (3) trust propensity. This distinction can be applied to trust initiations on the Airbnb platform. First, trustworthiness refers to the ability, willingness, and integrity of the Airbnb host, which is based on guests' familiarity with online (booking) transactions. Online marketplaces such as Airbnb have established institutional-based trust mechanisms, such as the verification sign on the profile of the hosts and the guests, as well as payment security services, to decrease transaction risk and encourage online transactions (Ert et al., 2016). In addition, there is the possibility of linking Airbnb with other social media profiles (Edelman & Luca, 2014). Second, initial trust refers to the guests' initial perception of the Airbnb host, describing their intention to accept vulnerability based on the positive expectations of subsequent actions, i.e., booking an accommodation. In fact, it is a context-dependent subjective personal characteristic of a specific Airbnb host gauged by a specific guest. Each Airbnb host has his/her own profile page that includes photos, a text-based self-description, and a review feature that gives both the host and guest the chance to post public reviews about each other in order to increase the trustworthiness of both parties. Although the Airbnb host is able to self-censor certain information and create the most positive self-image, the amount and type of self-disclosure by the Airbnb host determines the initial trust established by the Airbnb guest (Ma et al., 2017). Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 2: A profile presentation with high self-disclosure yields a higher level of trust than one with low self-disclosure.

Nevertheless, although online self-disclosure might lead to a higher level of trust, there will always be differences in uncertainty because of the trust propensity of the Airbnb guest. Trust propensity refers to the distinct dispositional attribute and the general tendency to trust others, i.e., the willingness to depend on situations, persons, or both, and the independence of the Airbnb booking environment (Broeder, 2020).

2.3 Cultural differentiations: uncertainty avoidance

Airbnb guests from distinct cultures vary in the degree of uncertainty avoidance. This is one of the dimensions in Hofstede's most commonly used cross-cultural paradigm (Hofstede et al., 2005). Cultural differences in uncertainty avoidance refer to "the extent to which the members of institutions and organisations within a society feel threatened by uncertain, unknown, ambiguous or unstructured situations" (Hofstede, 2023). Recent empirical investigations by Minkov and Kaasa (2021) and Minkov (2018) have suggested reconceptualising Hofstede's uncertainty avoidance dimension. These authors suggested splitting up cultural uncertainty avoidance into a culture's rule-orientation level and a culture's ambiguity-stress level. Elaborating on this, Kaasa (2021) showed the conceptual overlap between Hofstede's dimension of uncertainty acceptance vs avoidance, Schwartz's (2004) distinction between conservatism vs affective autonomy (reflecting values such as social order, obedience, and an exciting life) and, partly, Inglehart's (2021) distinction between self-expression vs survival [reflecting values such (in)tolerance and (in)security].

Several studies have empirically investigated the culture-related differences in the peer-to-peer shared economy for uncertainty avoidance and consumers' online trust (Sahi et al., 2016; Zarifis, 2019) and behavioural intentions (Gupta et al., 2019; Lim et al., 2004). Specifically, for the shared economy of Airbnb, two cross-cultural studies have focused on the degree of self-disclosure of the host expressed through visual cues. First, Broeder and Remers (2018) investigated the effects of eye gaze and visual self-disclosure cues among Dutch and French visitors. An Airbnb host profile with direct eye contact (i.e., the host looking the visitor in the eye) was compared with a profile without eye contact (i.e., the host looking away from the visitor). In a follow-up study, Broeder and Crijns (2019) examined the effects of visual self-disclosure cues among Dutch and Bulgarian visitors. In this study, the effects of (the same) high self-disclosure host profile with direct eye contact was compared with a low self-disclosure profile (the host was wearing dark sunglasses). In both studies, the results revealed that the level of self-disclosure presented by the profile pictures indirectly affected booking intention. Specifically, the host with direct eye contact was more persuasive compared to the host with no eye contact (either looking away or wearing dark sunglasses). Moreover, self-disclosure with direct eye contact enhanced the level of perceived trust, which in turn induced the intention to book the Airbnb accommodation. No support was found for the assumed moderating effect of culturally differentiated uncertainty avoidance for the Bulgarian, Dutch, and French individuals. This might have been because of these groups' lack of cultural differences. Against this background, in the present study, the following hypothesis is posited:

Hypothesis 3: Cultural background (differentiated by uncertainty avoidance) influences the relationship between the host's profile presentation and the guest's trust and booking intention.

The current study will focus on the Netherlands and China in order to examine potential cultural differences when booking on Airbnb. Hofstede (2023) expressed the cultural dimensions for the national cultures of countries in an index on a 0-100 scale. According to Hofstede (2023), China has a low uncertainty avoidance culture (a score of 30 on a 0-100 scale): "… adherence to laws and rules may be flexible to suit the actual situation and pragmatism is a fact of life. The Chinese are comfortable with ambiguity." In comparison, the Netherlands has a slight preference for avoiding uncertainty (with a score of 53), reflecting more that "… an emotional need for rules … and … security is an important element in individual motivation" (Hofstede, 2023; Broeder, 2022a).

3. Method

3.1 Design

The study had a two (self-disclosure: explicit; implicit) by two (culture: Chinese; Dutch) between-subjects design. The dependent variable was booking intention. In the research model, trust was the mediator reflecting an indirect effect of the self-disclosure type on the booking intention. Culturally specific uncertainty avoidance was assumed to moderate the relationships between the self-disclosure type, trust, and booking intention.

3.2 Sample

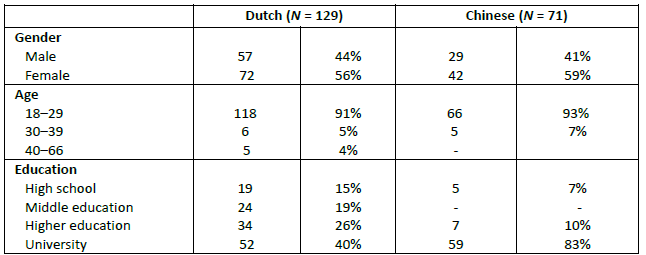

In total, 222 individuals completed the quantitative online survey. Data were not analysed from 22 individuals living/born outside China (specifically, 20 from Singapore and two from Malaysia). Altogether, 129 participants were from the Netherlands and 71 from China. Their Chinese or Dutch background was checked by asking the question "To what ethnic group do you belong?" The final sample used in the analyses consisted of 86 male and 114 female respondents. The mean age was 24 years (age range: 18-64). The reported education level of most participants was higher education or university. It can be assumed that their English proficiency level was high enough to justify the stimulus material and questionnaire being provided in English (see below). The demographic distributions of the sample are presented in Table 2.

3.3. Stimulus material

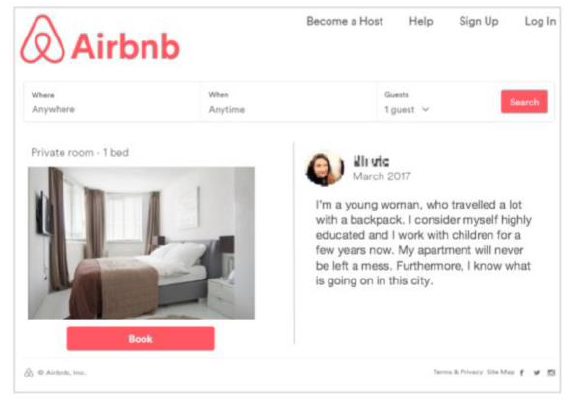

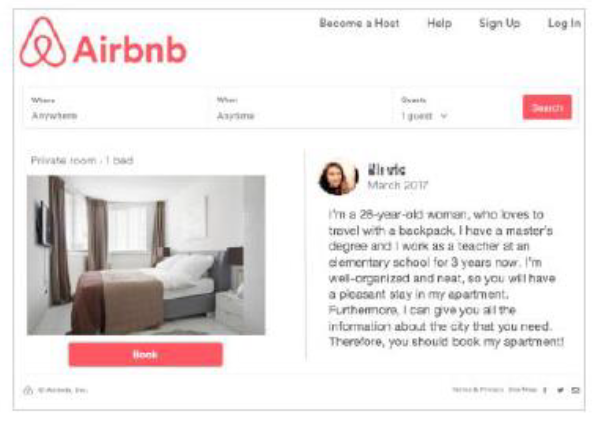

The participants were asked to imagine a scenario in which they were going to book an accommodation on Airbnb. They were presented with the Airbnb accommodation offer and were asked to read the personal description of the host carefully. There were two variations of the host's description: implicit self-disclosure (Figure 1); and explicit self-disclosure (Figure 2).

The description was written in English, in the present tense. The precise text for the implicit self-disclosure and the explicit self-disclosure presentation is shown for comparison in Table 3.

The two texts reflected the two different types of self-disclosures. In sentence 1, emotion was added in the implicit self-disclosure through an emotional style and personal involvement ("a lot"). In the explicit self-disclosure, a verbal emotion label was added ("loves") (cf. Derks et al., 2008). Sentence 2 was derived from Ma et al. (2017), who stated that hosts on Airbnb tend to share some personal information on education and work experience. In the explicit self-disclosure, this was factual information which could be verifiable ("Master's degree," "elementary school teacher," and "3 years"). By comparison, the implicit self-disclosure left room for guest-dependent interpretation ("highly educated," "working with children," and "a few years") (Yus, 1999). In sentence 3, the implicit self-disclosure focused on the apartment ("never left a mess"). In contrast, in explicit self-disclosure, the host was the focus. She said about herself that she is "well-organised and neat." Hence, her conclusion ("So") is that the guest would have a pleasant stay. Sentences 4, 5, and 6 reflected the difference between the sender and the receiver addressed. While the reader was not addressed in the implicit self-disclosure, the pronoun "you" was used in the explicit self-disclosure. Finally, in sentence 6, in the explicit self-disclosure, a direct recommendation for booking the room was expressed.

The development of the stimuli was based on examples from the official Airbnb website (in 2017). This meant a white background and the colour pink for the logo and some buttons. The text font used was Helvetica Neue in the colour dark grey. In addition, the upper part showed the enhanced Airbnb logo and some website functionality buttons ("Become a host," "Help," "Sign Up," and "Log In"). On the left side, the middle part showed the room accommodation with a short type of identification ("Private room - 1 bed"), with a "Book" button below this. The right side included the personal self-description, accompanied by a photo and name, both blurred, of the Airbnb host. The bottom part of the stimulus showed the Airbnb copyright logo, some standard buttons ("Terms & Privacy," "Sitemap") and some social media logos.

3.4 Procedure and measures

Data were collected in April/May 2017 through snowball sampling, via social media (such as WeChat, WhatsApp, and Facebook), of acquaintances in China and the Netherlands. The respondents participated in this study through an online link to the Qualtrics survey. They were randomly assigned to one of the two Airbnb accommodation offers that only differed in the degree of self-disclosure of the host, as detailed in 3.3. The online questionnaire was in English and included the following information:

Demographic information: age; gender; and education level ("What is the highest education level that you have completed?").

Following Broeder (2022a), culture-related information referred to birth-country ("What country were you born in?"), country-of-living ("In what country do you live at the moment?"), and ethnic self-identification ("To what ethnic group do you belong?").

Booking intention was measured with one statement ("I would like to book this accommodation"). Answers were given on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = "Completely disagree" to 5 = "Completely agree."

The trust scale consisted of five statements with a five-point Likert-type scale: "Overall, this host appears very trustworthy;" "This host appears to be considerate of another's feelings;" "This host appears to be friendly;" "This host appears to be unreliable;" and "I have the feeling that it would be better not trust this host." This scale had good reliability in this sample (Cronbach's α = 0.838).

The uncertainty avoidance measure was adapted from a scale developed by Jung and Kellaris (2004) based on Hofstede's dimension (Broeder, 2022a). There were six items using a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = "Completely disagree" 7 = "Completely agree." The three rule-orientation items ("I prefer structured situations to unstructured situations;" "I prefer specific instructions to broad guidelines;" and "I believe that rules should not be broken for merely pragmatic reasons") had poor internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.581). The three tension-oriented items ("I tend to get anxious easily when I don't know an outcome;" "I feel stressed when I cannot predict consequences;" and "I don't like ambiguous situations") had a good reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.797).

The participants were asked to what extent they were familiar with Airbnb (on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = "Completely disagree" to 5 = "Completely agree") and to what extent they trusted Airbnb (on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = "Not trustworthy" to 5 = "Trustworthy").

Finally, the participants specified how often they booked an accommodation via Airbnb or online (answers varied from "Once a month" to "Never").

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary analysis

Some preliminary analyses were performed for the attitude of the participants towards Airbnb. First, on average, there was no statistical difference in the familiarity with Airbnb between the Dutch group (M Dut = 3.78; SD Dut = 1.09) and the Chinese group (M Chi = 3.54; SD Chi = 1.11) [t(197) = 1.418; p = 0.158]. Also, regarding trust in the Airbnb platform, no statistical difference was found between the Dutch (M Dut = 3.72; SD Dut = 0.80) and Chinese (M Chi = 3.80; SD Chi = 0.86) respondents [t(197) = -0.648; p = 0.518].

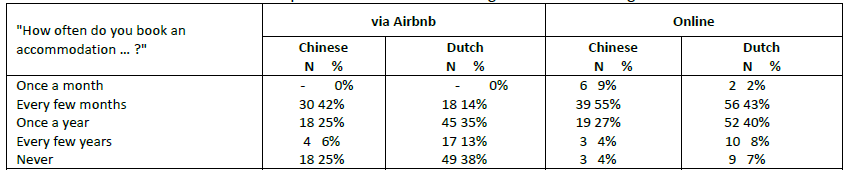

Second, as seen in Table 4, the Chinese participants seem to have more experience booking accommodation via Airbnb or online compared to the Dutch participants. A chi-square test showed no significant association between Airbnb booking experience and Airbnb booking intention, both in the Dutch group [χ 2 (12, N = 129) = 22.465, p = 0.03, phi = 0.417] and the Chinese group [χ 2 (12, N = 70) = 15.175, p = 0.232, phi = 0.466].

Finally, a comparison was made between the two cultural groups differentiated by the degree of uncertainty avoidance. On average, for rule-oriented uncertainty, there was no significant difference [t(198) = 0.37; p = 0.422] between the Chinese (M Chi = 4.82; SD Chi = 1.02) and Dutch (M Dut = 4.93; SD Dut = 0.84) respondents. In contrast, for tension-oriented uncertainty, there was a significant difference [t(198) = -2.20; p = 0.029] between the Chinese (M Chi = 4.73; SD Chi = 1.32) and Dutch (M Dut = 4.33; SD Dut = 1.22) respondents. Specifically, this suggests that the Chinese Airbnb guests are relatively more likely to avoid uncertain booking situations compared to the Dutch guests. This is in line with Hofstede's cultural comparison, which indicated that China has a higher uncertainty avoidance culture than the Netherlands.

4.2 Hypotheses testing

4.2.1 Intention to book the accommodation

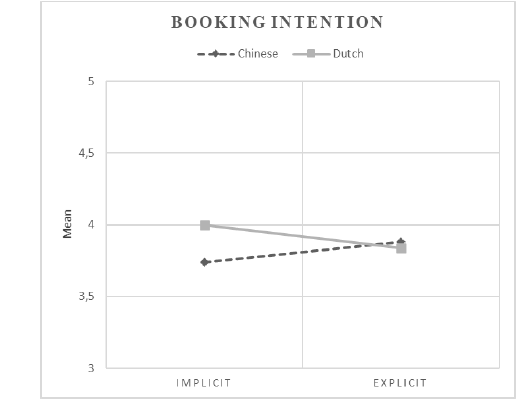

The average levels of booking intention for the implicit condition and explicit condition for both groups are plotted in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Booking intention per condition and per cultural group. Note: (Mean scores on a 5-point Likert-type scale, "Completely (dis)agree", Min. = 1 and Max. = 5).

In the implicit self-disclosure condition, the mean booking intention of the Dutch group (M Implicit = 4.00; SD Implicit = 0.945) was higher compared to the Chinese group (M Implicit = 3.74; SD Implicit = 0.815). However, given that t(95) = 1.309 and p = 0.194, this difference in booking intention between the cultural groups (M diff = 0.26) was not statistically significant. This finding did not support H3 for cultural differences.

In the explicit self-disclosure condition, the means were at the same level for the Dutch group (M Explicit = 3.84; SD Explicit = 0.884) and the Chinese group (M Explicit = 3.88; SD Explicit = 1.017). A two-by-two between-groups analysis of variance was conducted to explore the impact of self-disclosure and culture on the levels of booking intention. The interaction effect was not statistically significant. The main effect for the condition did not reach statistical significance [F(1, 196) = 9, p = 0.925]. This implies that a profile presentation with high self-disclosure did not generate higher booking intentions than the one with low self-disclosure (not confirming H1).

Moreover, culture had no statistical main effect on booking intention [F(1, 196) = 670, p = 0.014]. This shows that cultural background did not influence the relationship between the host's profile presentation and the guest's booking intention (not supporting H3).

4.2.2 Trust in the Airbnb host

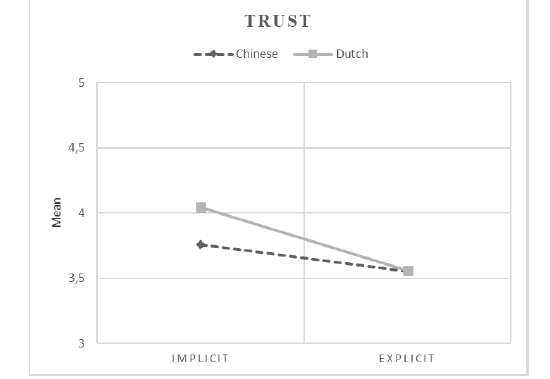

The average levels of trust for the implicit and explicit conditions for both groups are plotted in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Trust per condition and per cultural group. Note: (Mean scores on a 5-point Likert-type scale, "Completely (dis)agree", Min. = 1 and Max. = 5).

Figure 4 shows that, in the implicit self-disclosure condition, the mean trust of the Dutch group (M Implicit = 4.04; SD Implicit = 0.638) was significantly higher compared to the Chinese group (M Implicit = 3.76; SD Implicit = 0.491) [t(92) = 2.114; p = 0.037]. This difference in trust in the implicit disclosure condition (M diff = 0.28) supports H3 for cultural differences.

In addition, trust in the host decreased with the explicit disclosure type. Both the Dutch (from M Implicit = 4.04 with SD Implicit = 0.64 to M Explicit = 3.56 with SD Explicit = 0.62) and the Chinese groups (from M Implicit = 3.76 with SD Implicit = 0.49 to M Explicit = 3.55 with SD Explicit = 0.49) had higher levels of trust in the implicit condition compared to the explicit condition. A two-way between-groups analysis of variance was conducted to assess the effect of self-disclosure on trust for the Dutch and Chinese groups. The interaction effect was statistically not significant. In this analysis, the main effect for the condition was statistically significant [F(1, 188) = 14,350, p < 0.001], although the effect size was small (η p 2 = 0.07). This finding was in contrast with what was assumed by H2. The profile presentation with high self-disclosure yielded less trust than one with low self-disclosure.

Finally, in the analysis of variance, the main effect of culture on trust did not reach statistical significance [F(1, 188) = 2,477, p = 0.117]. The cultural background did not moderate/influence the relationship between the host's profile presentation and the guest's trust in the host (not supporting H3).

5. Discussion and implications

The findings of the experimental survey in this study are rather surprising. They provide some valuable insights regarding generating trust to influence customers' booking intention. First, an explicit self-disclosure profile did not yield higher booking intentions than an implicit self-disclosure profile. A second finding is that an explicit self-disclosure profile evoked less trust than an implicit self-disclosure profile. Finally, some cultural differences were found in the present study. The Chinese and Dutch groups differed in the degree of uncertainty avoidance. Specifically, the Chinese reported higher tension-oriented uncertainty than the Dutch. Confronted with the implicit self-disclosure profile, the Dutch participants reported relatively higher levels of booking intention and more trust compared to the Chinese participants. These differences between the two cultural groups disappeared with the explicit self-disclosure profile.

The findings of this study empirically support the reconceptualisation of Hofstede's uncertainty avoidance dimension by Minkov and Kaasa (2021) and Minkov (2018), splitting up cultural uncertainty avoidance into a culture's rule-orientation level and ambiguity-stress level. Further investigations of the uncertainty avoidance dimension require an emic perspective that emphasises the cultural specifics. In this context, the use of the native language of the members of specific cultures would be more appropriate that is, make culturally specific characteristics of the self-disclosure profiles more pronounced [see Bader et al., 2021 and Harzing et al., 2021 for the measurement of cross-cultural noninvariance].

In the present study, both cultural groups trusted the Airbnb platform for the dynamic attitudinal perceptions of Airbnb in society. In fact, the Chinese participants reported more experience with booking accommodation via Airbnb than the Dutch participants. Nevertheless, Airbnb is embraced in the Netherlands, as in most Western societies. In contrast, in Chinese society, Airbnb struggled to gain a foothold in this culturally unique environment (Xiang et al., 2021). Initially, Chinese tourists did not like to use peer-to-peer accommodation platforms in languages other than Chinese and went instead to Chinese facilitators such as Tujia, Xiaozhu, and Meituan. In this unique tourist accommodation market, Airbnb was forced to introduce a Chinese name (爱彼迎, meaning "Love enables us to welcome you") and to launch a website in the Chinese language (Xiang & Dolnicar 2018) two years after entering the Chinese market. Airbnb localising its name and product in the Chinese market greatly impacted trust and user perception. The local accommodation strategy was successful, and they survived in the face of competition from local competitors. By the end of 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Airbnb had gained more than 50% of the Chinese domestic market (Xiong et al., 2020). Remarkably, Airbnb announced that it would be quitting China from July 30, 2022, as lockdowns were restricting tourism post-COVID-19.

This study contributes to the emerging literature on the sharing economy and the influence of the self-disclosure of the goods and services provider on sharing economy websites on consumers' behavioural intention. Specifically, the findings have direct implications for improving the textual design of personal descriptions on profile pages, with the aim of promoting trustworthiness. This information is interesting for individual providers of goods and services, as they can make use of explicit self-disclosure in online profiles to influence the trust of consumers. It might also be important for most companies within the sharing economy because they can adjust their language in marketing activities in such a way that the consumer's attitude is positively influenced.

6. Limitations and further research

This study has limitations that give rise to some suggestions for further research. A first limitation relates to the realism of the Airbnb context in which the room accommodation was offered. The current study strived to increase external validity by displaying a host's profile and a room accommodation offer that looked as real as possible within the survey. Nevertheless, there was only one Airbnb offer for the survey. This study investigated the effects of different types of self-disclosure instantiated via the use of verbal cues. More specific samples are suggested to test the hypotheses. Specifically, the host's self-disclosure can also be expressed via visual cues such as the type of (in)direct eye-gaze contact (Broeder & Crijns, 2019; Broeder & Remers, 2018). Further studies might investigate the holistic perception of the offers in which the specific verbal and visual cues are examined in combination or as a whole. In this respect, the relationship between visual and language cues is more complex than the mere presence effect (Li & Xie, 2020). The prominence and salience of the appeal in a product presentation might also depend on the relative importance of competing cues. Specifically, colour variations of the product context have been shown to provoke trust [with blue (Broeder & Van Doremalen, 2021)] or emotion [with red (Broeder & Wildeman, 2020)] within an online environment and culturally biased (Broeder, 2022b).

The second limitation is that the experimental stimuli were drafted in English, which is not the native language of either the Dutch or Chinese participants. Therefore, the findings are based on participants' interpretation of the fictional host's self-disclosure statements through more or less explicit language and presentation in English. In addition, the questionnaire language was also English. On the basis of the education level of the participants in this study (mostly higher education/university), it can be assumed that their English proficiency level was high enough to be able to interpret the hosts' self-disclosure. This can be inferred from Bowles and Murphy's (2021) review of the status of English in instructional practices for the internalisation of higher education and universities worldwide; specifically, see Wang (2020) for China and Wilkinson and Gabriëls (2021) and Wilhelm (2018) for the Netherlands. Elaborating on this, the decision to opt for English (in the host profiles and the measures) followed from the etic perspective taken in the present study (Harzing et al., 2021). The focus was on commonalities between cultures differentiated by the commonly evidenced dimension of uncertainty avoidance. In this respect, Harzing (2005) cross-country study showed the language impact on response patterns related to cultural values, such as the degree of individualism/collectivism of a society. Their empirical comparison of 24 countries confirmed earlier research that differences between countries are smaller for English-language questionnaires than for native-language questionnaires.

7. Conclusion

This study has investigated the effects of different types of self-disclosure by Airbnb hosts on Airbnb guests' trust and booking intention, differentiated between the Western culture of the Netherlands and the Asian culture of China. Contrary to expectations, the result suggested that implicit language in self-disclosure by the Airbnb host led to more trust than explicit language. In addition, the findings indicated that Dutch Airbnb guests had higher booking intentions and more trust in the Airbnb host after reading an implicit self-disclosure compared to the Chinese guests. These cultural differences disappeared with the explicit self-disclosure profile. Although no direct effects of the type of language in self-disclosures (implicit vs. explicit) on booking intention were found, the results in this study have shown that implicit language in self-disclosure could have a positive influence on the trust and attitude of the customer. This may be valuable for providers of goods (e.g., hosts on Airbnb) when creating a self-description for personal profiles on sharing economy websites because trust might have other positive influences that can be beneficial for the provider. Given the emergence of an increasingly globalised online environment, culture (as a set of individual shared common attitudes and beliefs) is likely to disperse, reinforcing culture-specific values. In the context of the shared economy, future studies should investigate how to fine-tune the persuasive information cues in marketing communications and product offerings to align with local consumers' preferences in social commerce platforms that are operating globally.