1. Introduction

The new information and communication era has brought an innovative toolkit to the tourism sector. This sector is one of the most suitable fields for information technology to be widely used from a business and operational point of view (Dorcic, Komsic & Markovic, 2019). Since 2004, online commerce has undergone a major change as online travel portals have become more sophisticated in terms of interaction capabilities and product and service offerings, and technology has extended the web's ability to both accommodate and stimulate growing customer demands (Beldona, Nusair & Demicco, 2009). As Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have developed, structural changes in tourism distribution channels (TDCs) have occurred, giving rise to the emergence of a new tourist, the digital tourist (García, Berné, del Carmen & Orive, 2015). Digital tourists use the Internet to plan trips, i.e., seeking information, particularly through social media such as blogs, websites or social networks (Tilly, Fischbach & Schoder, 2015), booking or paying for some aspect of the trip (Creevey, Kidney & Mehta, 2019; Mendes-Filho, Mills, Tan & Milne, 2017). According to Canalís (2018):

Before travelling, 88% of tourists look for information online, and 82% buy or book something (accommodation, transportation, activities).

During the trip, 44% of tourists purchase activities, and 86% use applications to enhance their experience in the destination.

After travelling, 61% of tourists engage in digital activities related to their post-trip experience, and 71% of travellers conducted travel-related searches from a smartphone, up from 56% in 2016.

Tourism distribution involves numerous agents who participate in the distribution channels that constitute the system. It is a system of intermediation that facilitates the provision of tourism services from the supplier to the consumer (Buhalis & Laws, 2001). Due to internet penetration, the emerging online distribution channels (ONDCs) bring great strength to classic offline distribution channels (OFDCs), mainly in business-to-consumer (B2C) transactions. The literature acknowledges that ICTs change the role of tourism stakeholders who must continuously keep up with a shifting working environment (García et al., 2015). The technological application has fostered the appearance of ONDCs and has disrupted the involvement of the diverse actors within it and the power relations between its participants (Berné, García-González, García-Uceda & Múgica, 2015). This adaptation effort leads to the reactivity that develops in the tourism framework and the need for more competitive and proactive channels (Buhalis & Law, 2008).

The advantages of ONDCs, compared to OFDCs, consist of the ease of purchasing and booking and information wealth (Lee, Yoon & Park, 2017). These channels give individuals control and greater independence, promoting self-learning and personal growth. Their use enables travellers to move at their own pace, plan customised routes and live deeper experiences at destinations that will allow them to appreciate local cultures better. As a result, greater effectiveness and efficiency in trip preparation is achieved (Kim, Chung & Lee, 2011). These gains are achieved through autonomous behaviours by travellers throughout all phases of a journey, but especially during the planning stages (Fernández-Herrero, Hernández-Maestro & González-Benito, 2017), which can lead to higher belief in the brand of the company and the destination, satisfaction and post-trip loyalty (Creevey et al., 2019). Regarding tourism businesses, according to García et al. (2015), those that embrace ONDCs become more able to compete and gain more power within TDCs. For this reason, companies that used to operate in the traditional market have jumped into the online channel, looking to maximise the cost reductions that technology provides.

Drastic changes and challenges have occurred in distribution channel systems since the penetration of electronic distribution channels into the tourist industry, especially online travel agencies (OTAs), resulting in a seismic change from the traditional offline channels dominated by tour operators (Wang, 2023). Although authors (e.g., Cooper, Fletcher, Fyall, Gilbert & Wanhill, 2013; Peng & Lai, 2014) argue that the Internet and e-commerce have contributed positively to the tourism industry, its entry into the system is fairly new, and background research on the development of this channel and system-wide alterations is still lacking. Few studies focus on empirical analyses of digital transformation in tourism. For example, Kontis & Skoultsos (2021) explore hoteliers' opinions regarding emerging changes in tourism distribution in the digital age. Therefore, there is a strong need for continuous research into transforming distribution channels in the tourism and hospitality context (Soltani-nejad, Irani, Soltani & Yazdani, 2022).

Considering the importance of tourist satisfaction and loyalty to achieve a competitive and resilient tourism destination (Fernández-Herrero et al., 2017), it is essential to understand what the new digital tourist profile is like and how these tourists when planning their trips to develop effective communication and marketing strategies that attract and retain them (Xiang, Wang, O'Leary & Fesenmaier, 2014). The academic literature has focused much effort on the study of tourism satisfaction and loyalty and, to a greater extent, on its antecedents, most notably tourists’ profiles, motivations, involvement, perception of quality, previous experiences, destination image, place attachment, and perceived value (Chen & Tsai, 2007; Faullant, Matzler & Füller, 2008; Forgas-Coll, Palau-Saumell, Sánchez-García & Callarisa-Fiol, 2012; Gursoy, Chen & Chi, 2014; Jayasinghe, Gnanapala & Sandaruwani, 2015; Wang, Wu & Yuan, 2010; Yuksel, Yuksel & Bilim, 2010). However, according to Fernández-Herrero et al. (2017), limited research has addressed the possible relationship between tourists' autonomy due to the use of ONDCs and their trip satisfaction and loyalty. Thus, further studies are recommended to understand better how using the Internet to organise trips will improve digital tourist satisfaction and loyalty (Fernández-Herrero et al., 2017).

In addition, it is important to note that tourism distribution channels differ in terms of products, industrial fabric and places (Buhalis, 2000). Specifically, rural tourism in inland areas of Spain is located in an enclave of depopulation with a lack of digital accessibility and connectivity (Bandrés & Azón, 2021). This situation negatively impacts economic, environmental and sociocultural aspects, influencing the configuration of the tourism distribution system (Serra, Pallares-Barbera & Salvati, 2022). As a consequence, public institutions develop plans such as the "Plan for the digital transformation of tourist destinations" within the 130 Measures to face the demographic challenges aimed at improving the competitiveness and resilience of rural tourist destinations based on innovation and digital transformation. In parallel, measures are established to promote the digital transition and full territorial connectivity.

The digital transition is configured as a backbone of social and territorial cohesion, revitalising the areas most affected by depopulation, creating the necessary conditions for entrepreneurship and job creation (Gobierno de España, 2023). This is why tourism is positioned as an engine of rural development to tackle the problem of depopulation, reinforcing connectivity and equipment and, therefore, the quality of life of residents (Campón-Cerro, Hernández-Mogollón, & Alves, 2017; Prat Forga, 2020; Baptista Alves, Pires Manso, da Silva Serrasqueiro Teixeira, Santos Estevão & Pinto Nave, 2022; Gatto, Santopietro & Scorza, 2022).

Regarding the choice of this region, the province of Burgos reflects a decline in the total population and the significant ageing of the population (De la Iglesia, 2023). Additionally, there are few studies on tourism in the province of Burgos (Spain) (Antón Maraña, Aparicio Castillo, Puche Regaliza & Arranz Val, 2021), which leads this work to further analyse the tourism sector in this rural inland area. Due to the cultural and patrimonial wealth that is present in this territory, tourism is a sector that promotes economic activity and thus has the potential to contribute to achieving sustainable development goals in this area (UNWTO, 2021). For example, in 2021, the hospitality sector generated 7.44% of the total direct employment in Burgos. Tourism demand indicators show a 25% increase in the number of travellers from 2015 to 2019 and a 26% increase in overnight stay figures in the same period (JCyL, 2021). Compared to other destinations in Spain, Burgos ranks fifth in inland tourist cities according to EXCELTUR (2017). These figures demonstrate the importance of the tourism sector in this region and, together with the digital transition, can help to address the demographic challenge it faces.

Such is the need to optimise the province's competitive advantages, and the Society for the Development of the Province of Burgos (SODEBUR) has developed the Burgos Rural Strategic Plan 2025, implementing the digital transition in all economic and social activities of the province, especially in supporting digitalisation in rural tourism (SODEBUR, 2023). Following this line, SODEBUR, in collaboration with the University of Burgos, has carried out a study to analyse the extent to which there is a change in the use of TDCs by tourists visiting Burgos, with the aim of demonstrating the usefulness of technological innovations in rural tourism destinations.

We consider that improving decision-making in terms of digital transformation in rural destinations can increase the competitiveness of the province and tackle the problem of depopulation by satisfying and retaining tourists who can become new inhabitants in environments prone to population loss (Dot Jutglà, Romagosa Casals & Noguera Noguera, 2022).

To fill the research gap, this study aims to explore whether the change in the trend of the use of TDCs is reflected in the tourists visiting the province of Burgos and whether tourism agents benefit from this phenomenon.

In particular, this research seeks to tackle these objectives:

To determine the effects of ONDCs in trip planning on enhancing tourist satisfaction and tourist destination loyalty, the use of quantitative methodology through the calculation of logistic regressions is deemed appropriate for this purpose.

To differentiate tourists with a digital profile from tourists with a traditional profile who resort to traditional or OFDCs to plan their visits.

Thus, the main contribution of this work is an empirical exploratory analysis that enables the study of the transformation of distribution channels in the tourism industry and to what extent tourist satisfaction and loyalty are influenced by these changes. It is applied to a case study, the province of Burgos, whose inland rural destinations face the problem of depopulation. This is the first empirical study focusing on the transformation of distribution channels in the Burgos tourism industry. In addition, the effects of the use of online channels in trip planning on satisfaction and loyalty are assessed in a differentiated way without assuming their interrelation.

This paper proceeds with a literature review that serves to formulate the hypotheses and find the research gap. Then, the research methodology and findings are presented, from which the discussion and main conclusions are drawn.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Tourism Distribution System

Travel consumption and planning may be identified as a particular kind of consumer purchase. In the hospitality and tourism sector context, much research has been conducted on how people plan trips and consume services and products (Xue, Shen, Morrison & Kuo, 2021). Although there has traditionally been a consensus to differentiate the phases in the tourist decision-making process (pre-, during and post-trip) (Fernández-Herrero et al., 2017) since the emergence of online platforms, further stages can be differentiated. Now, a travel behaviour cycle can be split into intention triggering, seeking information about the trip, product booking, product use during the trip and personal experience sharing after the trip (Xue et al., 2021).

Additionally, tourists are turning to global distribution channels such as web travel agencies or search engines targeted to travel (e.g., Expedia, Trabber, Kayak, Logitravel) to consume information (Xiang et al., 2014) on tourist offerings and to share online shopping reviews (Xue et al., 2021). Also, the Internet may be used by tourists to book or pay for any aspect of the visit. According to ONTSI (2020), in terms of spending volume, tourism and transport are leaders in online sales.

As a consequence of these changes in both distribution channels and tourist behaviour, a new paradigm in the tourism distribution system has emerged, characterised by a more thorough preparation for the trip before departure by searching for information and making reservations and purchases of tourism products and accommodation on online platforms (Xue et al., 2021).

Needless to say, these changes brought about by the proliferation of ICTs and the Internet imply greater challenges for tourism destinations. They must allocate resources to position themselves on social media platforms and networks to face increased competition online but without neglecting to offer memorable experiences to tourists. Although the distribution system has changed, one of destinations' main objectives is still attracting and retaining tourists. Therefore, professionals and scholars are trying to focus on studying tourist satisfaction and loyalty in this new online scenario (Torres, Fu & Lehto, 2014).

2.2 Trip Satisfaction

Tourist satisfaction has long been the focus of researchers' attention (e.g., Yoon & Uysal, 2005; Chen, Zhou, Zhan & Zhou, 2020).

Higher tourist satisfaction may result in positive word-of-mouth (WOM) and increased consumer loyalty (Kozak & Rimmington, 2000; Suhartanto, Ruhadi & Triyuni, 2016). Additionally, several studies point out that satisfied tourists are more likely to spend more than less satisfied tourists (Serra, Correia & Rodrigues, 2015; Smolčić-Jurdana & Soldić-Frleta, 2017).

Due to the high level of competition in the tourism market, tourist destinations must be more attentive than ever to the satisfaction experienced by tourists. Soldić-Frleta & Smolčić-Jurdana (2018) point to the paucity of research on the relationship between the use of ONDCs to organise visits and general tourist satisfaction. Additionally, based on the findings, the tourists the most satisfied with the online details reported higher overall satisfaction. This is because users take advantage of personalised, fast and reliable service, enhanced communication, increased connectivity and faster transactions, and these perks meet their expectations and needs.

Regarding searching for information, one of the main sources of information in tourism that significantly influences especially young people is recommendations through social media, as electronic word of mouth (eWOM) is perceived by tourists as a reliable source of information (Song, Liew, Sia & Gopal, 2021). For example, new emerging platforms such as TikTok impact how tourists get to know a destination and, thus, the expectations they create (Wengel et al., 2022). As a result, tourists idealise certain experiences and develop expectations that may not match reality (Ponte, Couto, Sousa, Pimentel & Oliveira, 2021). This can lead to dissatisfaction by comparing the expectations created prior to the trip with personal experiences (Li, Liu & Soutar, 2021).

Ferrer-Rosell, Coenders & Marine-Roig (2017) state that Internet booking allows tourists to identify low-price sellers through search engines, improving value for money, reducing the gap between expectations and perceptions and increasing consumption, thus enhancing travel satisfaction.

Previous research on pre-trip internet use broadly endorses the notion that the Internet enables travellers to choose better and acquire more in-depth information. By identifying various acknowledged academic links between internet use and trip satisfaction, a positive correlation between these two variables is assumed (Castañeda, Frías & Rodríguez, 2007; Fernández-Herrero et al., 2017; Ferrer-Rosell et al., 2017).

Therefore, the following is hypothesised:

H1: Tourists' use of an ONDC will have a significant positive effect on tourist satisfaction level.

2.3 Tourist destination loyalty

Consumer behavioural intentions are widely discussed in the tourism and hospitality field (Lim & Ayyagari, 2018; Ongsakul et al., 2021) given their substantial importance in recognising consumers' actual purchase behaviour (Hsu, Chang & Chen, 2012; Pelet, Ettis & Cowart, 2017; Wang, Law, Guillet, Hung & Fong, 2015). Favourable intentions include higher expenditure with the service supplier, positive WOM, paying a premium price and loyalty (Fong, Lam & Law, 2017; Wang et al., 2015).

Based on other work, loyalty is defined as tourists’ behavioural favourable intentions to recommend the visit to others both by WOM and eWOM and to revisit the destination (Azis, Amin, Chan & Aprilia, 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2015). Currently, eWOM is an influential source of information for consumers to make informed decisions and thus is highly valued by businesses (Garg & Kumar, 2021; Liu, Wu, Shi, Tong & Ye, 2022).

Social media is currently considered a very influential source of information for a wide audience of potential travellers, as it is how many tourists share their experiences, recommendations and opinions. In addition, this information affects tourists' revisit intentions (Nautiyal, Polus, Tripathi & Shaheer, 2023). It is important to consider the potential of online channels, as their rapid dissemination and wide reach can attract many tourists and have unintended consequences such as overtourism (Wengel et al., 2022).

Numerous studies try to identify which variables affect loyalty. For example, the results of Zheng, Wen Shen, Chau, Liu & Li (2021) show positive influences between emotional attachment, visitor satisfaction and perceived quality that can influence the conative loyalty of museum visitors. Generally, studies focus on attitudinal loyalty, most often used to understand tourists' loyalty to the destination, which concerns the psychological and emotional condition of tourists and their intention to visit again and to recommend a certain good or service to others (Chi & Qu, 2008; Wang, Liu, Huang & Chen, 2019; Yoon & Uysal, 2005).

Azis et al. (2020) demonstrate that the use of smart technologies, such as online travel agencies, smartphones, or social networks (Huang, Goo, Nam & Yoo, 2017), provides greater accessibility, informativeness, connectivity, interaction and personalisation to the tourism industry (Jeong & Shin 2019; Lee, Lee, Chung & Koo, 2018) and thus improves overall travel experiences (Simeon, Buonincontri, Cinquegrani & Martone, 2017) and enhances destination satisfaction and loyalty through positive memorable tourism experiences (Neuhofer, Buhalis & Ladkin, 2015). Torabi et al. (2022) show that enhancing memorable experiences by using smart tourism technologies influences positive satisfaction and revisit intentions. Additionally, Thao & Swierczek (2008) propose practical guidelines for reducing barriers to creating customer value and strengthening customer relationships and loyalty through internet use in the travel industry. It should be considered that loyalty has been identified as a crucial factor for the success and sustainability of a seller or brand over time (Thakur, 2016).

Therefore, the following is proposed:

H2: Tourists' use of an ONDC will have a significant positive effect on tourist loyalty.

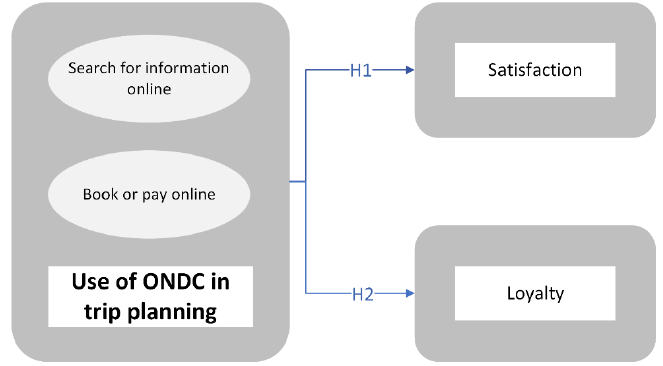

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model that illustrates the connections between the variables explained above, i.e., it reflects the hypothesised relationships. The relationships between the dimension of ONDC usage in trip planning, comprising two variables, online information search and online booking and payment, and the dimensions of satisfaction and loyalty, respectively, can be observed.

3. Methodology

This section presents the design of the data collection process, the sample and the analysis techniques.

3.1 Survey instrument

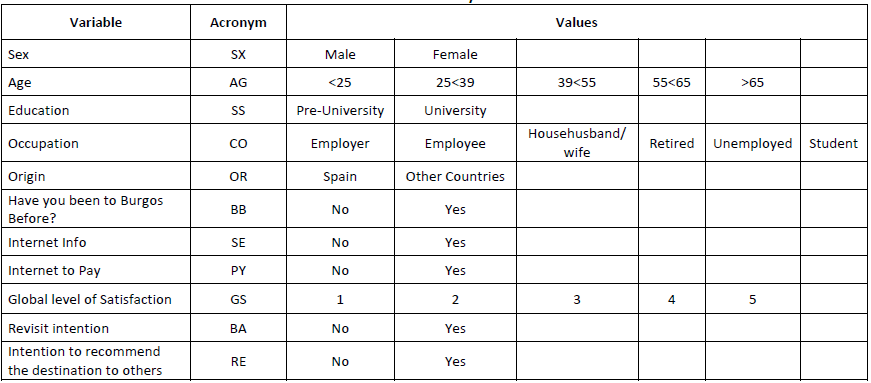

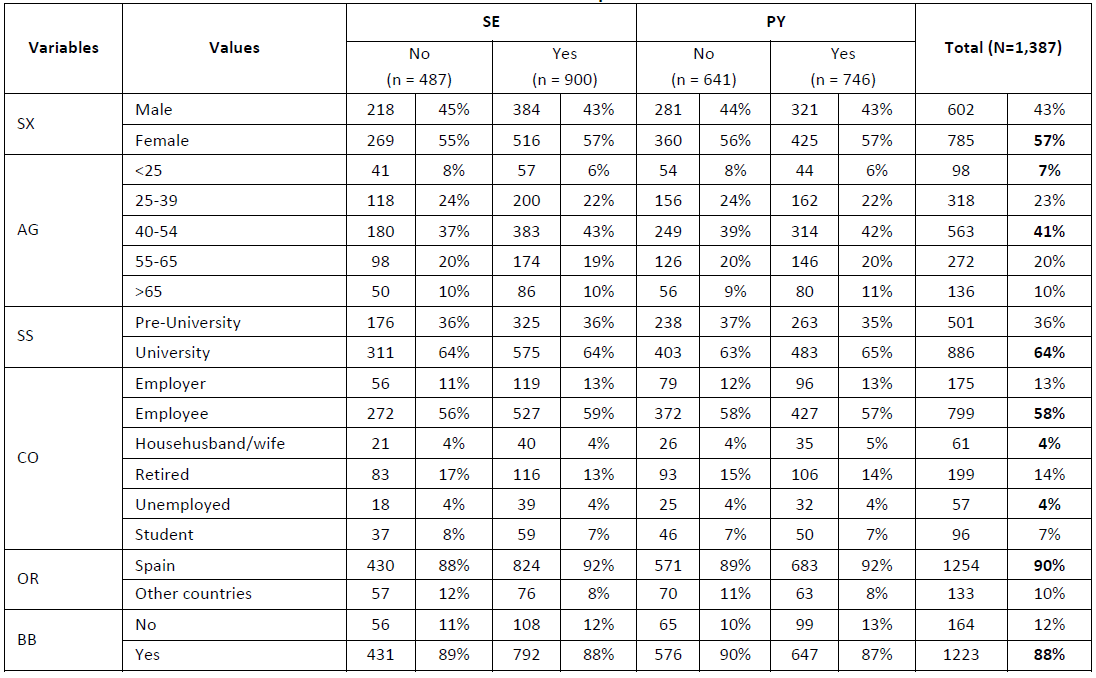

The results of this paper are based on data obtained from surveys conducted in Burgos Province by the Province of Burgos Tourism Observatory. Data were collected by administering a close-ended, structured questionnaire. The variables included in the questionnaire were chosen according to other scientific research (Benítez-Márquez, Bermúdez-González, Sánchez-Teba & Cruz-Ruiz, 2021; Hui, Wan & Ho, 2007; Ozdemir et al., 2012) and to studies carried out by other Spanish observatories, such as Seville, Alicante and Turespaña. The questionnaire covered questions on respondents' sociodemographic characteristics, their trip planning, their overall satisfaction measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 referring to highly dissatisfied and 5 to highly satisfied) and their intention to return and recommend the destination to others. A reliability of 0.78 (Cronbach’s alpha) for the measurement instrument was obtained. A value greater than 0.6 can be considered acceptable (Malhotra, 2009). Table 1 shows the different values taken by the variables included in the questionnaire.

The dichotomous variable “Internet Info” comprises 2 binary features stating whether or not the visitor used the Internet to search for information on one or more aspects of the visit. The dichotomous variable “Internet to Pay” comprises 2 binary features stating whether or not the visitor used the Internet to book or pay for one or more aspects of the visit. For clarification, the authors consider a digital tourist to be one who uses online channels in some aspect of the trip, in all of them, in combination with offline channels, or simultaneously.

To analyse the data, a new dichotomous variable, "Loyalty" (LO), was considered, which refers to whether the tourist is loyal to the destination. A tourist is considered loyal when he or she states that he or she intends to visit the destination again or to recommend the destination to others. As in other studies (Ozdemir et al., 2012; Song, Li, van der Veen & Chen, 2011), loyalty is measured by a 2-item scale (Yes or No) with regard to the intention to revisit and to recommend.

3.2 Sampling, data collection and data analysis

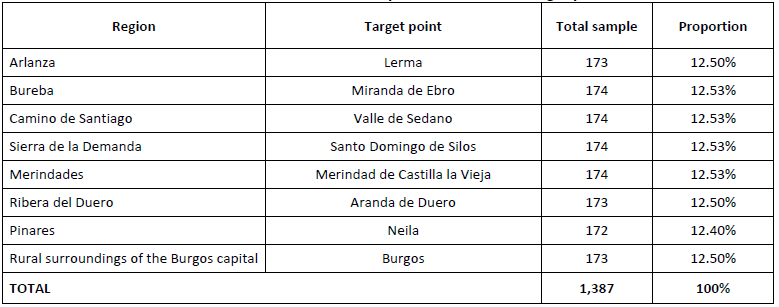

Stratified random sampling was used as the sampling technique, and it involves dividing the population into distinct subgroups (strata) based on the Touristic Potentiality Index for the province of Burgos (Aparicio-Castillo et al., 2023). As a consequence, eight target points for interviews were selected. Each stratum corresponds to the tourists visiting each of these target points. Then, each target point is randomly sampled. This ensures that each subgroup is adequately represented (Rahman, Tabash, Salamzadeh, Abduli & Rahaman, 2022). The distribution of the sample in the different regions and target points is shown in Table 2.

This sampling technique belongs to the group of probability sampling techniques that ensure that all people in the population have the same probability of being chosen. It is considered to be the best method of ensuring that the sample is random and that all sampling units are equally representative of their populations (Fowler, 2009).

The gathered data provide a confidence level higher than 98% for global data and a sampling error lower than 2.486%. The fieldwork was carried out by collaborators from tourist establishments and tourist offices throughout the year and, during the summer months (July and August), Christmas and Easter, by professors and students from the University of Burgos to guarantee a representative sample, since the number of tourists increases significantly during these months. Aiming for seasonality smoothing, satisfaction surveys have been conducted over time, not only during the high season. This ensures more effective destination management targeted at meeting the preferences of tourists (Bernini & Cagnone 2014).

The target population was those people not residing in nearby towns, over 16 years of age, who were visiting the province of Burgos and were randomly approached and interviewed face-to-face at different tourist places. Finally, after the corresponding cleaning process, a total of 1,387 valid surveys were obtained for data analysis. Once the data were collected, an exploratory empirical analysis was carried out by using IBM SPSS Statistics. First, some descriptive statistics were computed. Second, an ordinal logistic regression was conducted to determine the relationship between the independent variables (SE, PY) and the dependent ordinal variable (GS). Finally, a binary logistic regression was carried out to analyse the impact of the independent and dependent variables (LO).

4. Results

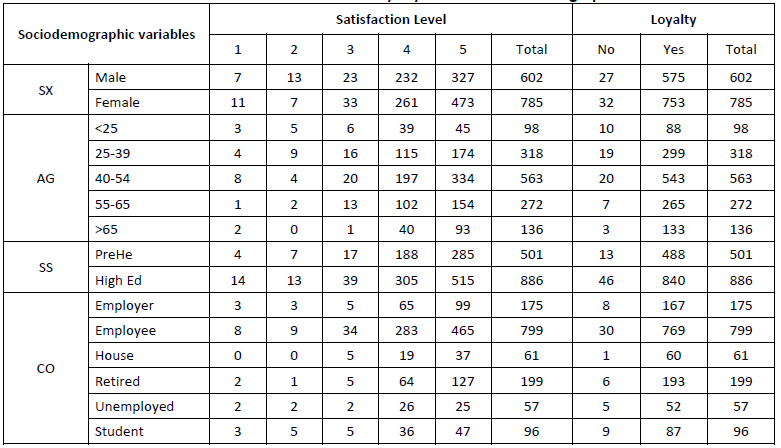

First, since the aim of the paper is to study tourist satisfaction and loyalty, we provide Table 3, which shows the differences in these two variables between men and women, different ages, different jobs and different levels of education. As seen, those tourists who are female, over 65 years old, have a high level of education and are retired have the highest satisfaction values. Regarding loyalty, there are no differences by sex, in contrast to the age ranges. The higher the age, the more likely a tourist is to be loyal. In addition, there are more loyal tourists with preuniversity education and who work at home. It is worth noting that the positive values for loyalty exceed 90% in all cases.

Table 4 presents the sociodemographic profile of the respondents. The majority of the respondents were female (57 per cent). Forty-one per cent of the respondents were between 40 and 54, and only 7 per cent were under 25 years old. Most respondents (64 per cent) had a bachelor’s degree. Regarding current occupation, 58 per cent of the participants stated that they were employees, and only 4 per cent were unemployed or engaged in household chores. While 10 per cent of the participants came from abroad, 90 per cent were from Spain. Finally, 88 per cent of respondents had visited the province of Burgos before. It is worth noting that in general terms, these data are maintained regardless of whether the tourist has used online distribution channels.

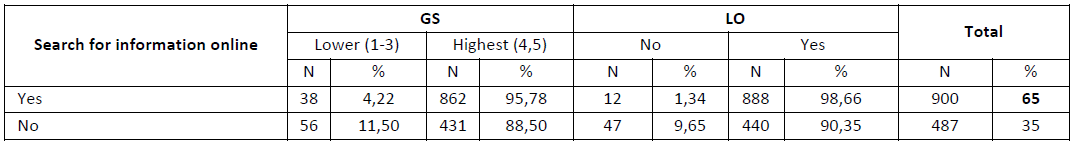

Next, a review of the data in Table 5 shows that of the 1,387 tourists surveyed, 65% search for information online. It can be seen that among those who do search, there is a high percentage of loyal tourists with high satisfaction and somewhat higher than among those who do not search. On the other hand, there is a notable difference between the proportion of nonloyal tourists with low satisfaction who do search and those who do not search, with the latter being considerably higher.

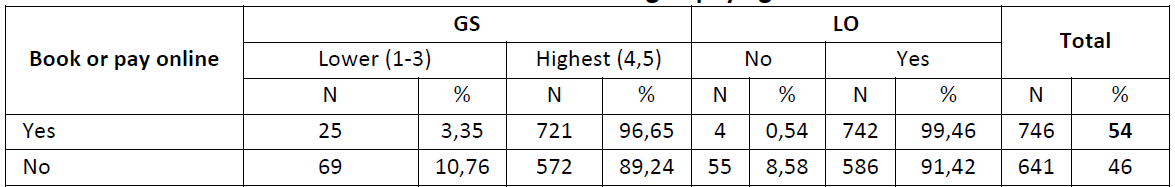

Even lower is the percentage of tourists surveyed who book or pay for any service online (54%). As in the previous case, there is a high percentage of loyal tourists with high satisfaction and slightly higher figures than those who do not hire or pay online.

In the case of nonloyal tourists with low satisfaction, the percentages are lower than those seen in the previous slide, although there is also a notable difference between those who book or pay online and those who do not (Table 6).

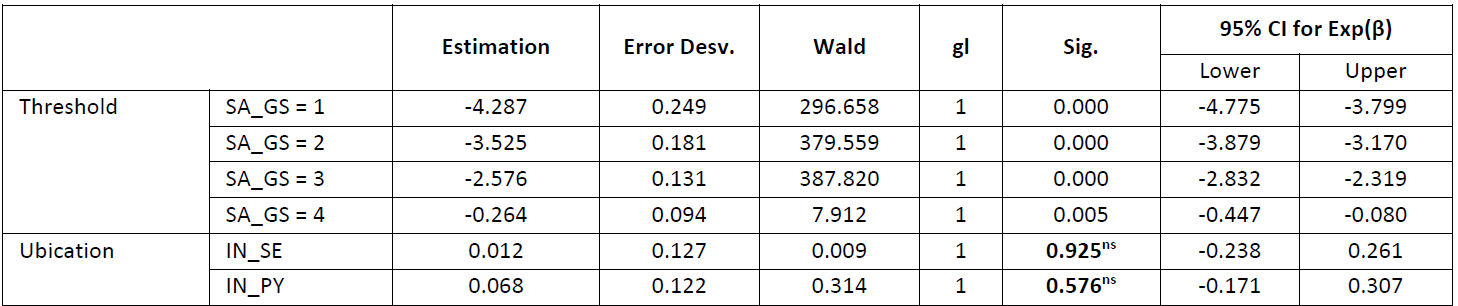

Ordinal regression analysis was conducted to investigate Hypothesis 1. First, the model fit significance (0.786) is greater than 0.05, so the model with the introduced variables does not improve the fit significantly with respect to the model with only the constant. Second, a Pearson's chi-square statistic (0.000) of less than 0.05 tests whether the observed data are inconsistent with the fitted model. The pseudo R-squared in the Cox and Snell test (0.000), Nagelkerke test (0.000) and McFadden test (0.000) summarises that the model does not explain the proportion of variability of satisfaction. Finally, as seen in Table 7, the results indicated that almost all the independent variables have very little significance in the model.

Table 7 Regression analysis for variables affecting satisfaction level

Notes: **p<0.001; *p<0.05; ns = not significant

In short, since the validity of this model cannot be shown, H1 is rejected, and thus, tourists' use of an ONDC will not significantly affect the tourist satisfaction level.

Next, a binary logistic regression was conducted to investigate Hypothesis 2. The method used to select the variables for the model is "Enter", as it allows the researcher to decide which variables are entered or extracted from the model. Before analysing the results, verifying whether the model truly fits the data is necessary. As there are two covariates entered into the model (in addition to the constant), a single step, block and model match all three values. The statistical significance of the chi-square test (0.000) indicates that the model with the new variables introduced improves the fit significantly with respect to the model considering only the constant term.

Second, the discrete Cox-Snell R-squared value (0.055) indicates that the independent variables explain only 5.5% of the dependent variable variation. The Nagelkerke R-squared value (0.186) reveals that this model explains a maximum of 18.60% of the collected data variability regarding the total number of loyal and nonloyal tourists. In other words, the model's independent variables account for a low percentage of the loyalty variable's variability.

Comparing the values predicted by the model with the values actually observed to study the goodness-of-fit of the logistic regression model, the significance value (0.896) of the Hosmer‒Lemeshow test confirms that the model fits the dataset properly. Nevertheless, the classification table is a logistic regression's most intuitive fit indicator. The global percentage of cases that classify the model correctly is 95.70%.

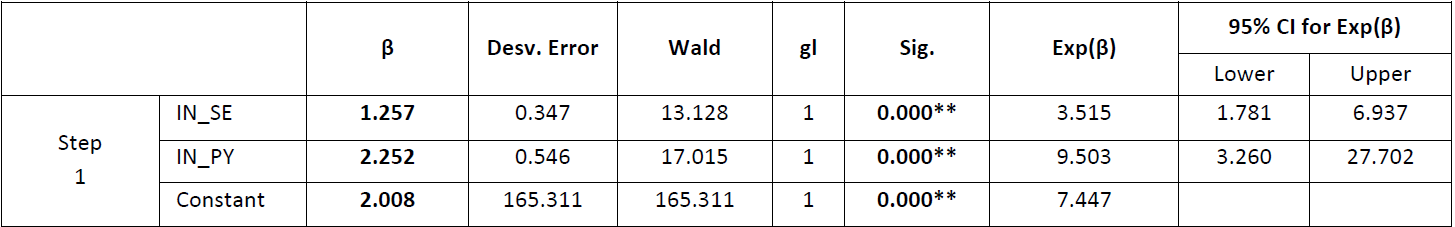

Finally, Table 8 shows the beta coefficients, which indicate the relative importance of each variable in the model. These coefficients suggest that the variable on whether the tourist has contracted or paid online (β=2.252) has the strongest positive impact on tourists' loyalty, followed by the constant (β=2.008) and by the variable "PY" (β=1.257). All beta coefficients have a null p value of significance (0.000<0.05), so they are statically significant and forecast whether a tourist is loyal or not (UCLA, 2021).

Table 8 Regression analysis for variables affecting loyalty

Notes: **p<0.001; *p<0.05; ns = not significant

The odds ratios of the predictors (Exp(B)) show how a unit change in the independent variable with which it is linked increases or decreases the occurrence vs. non-occurrence probability. All the independent variables' coefficients are positive and have an odds ratio greater than one, reflecting that the dependent variable is more likely to happen as the variable increases (Agresti, 2002; Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000).

In short, H2 is accepted, and thus, tourists' use of an ONDC will significantly affect tourist loyalty.

5. Discussion

This exploratory study provides meaningful results on the trend change in tourism behaviour, i.e., the shift from using traditional distribution channels such as tour operators and destination management companies (DMCs) to new digital channels such as online travel agencies (OTAs).

The development of ICTs, especially the proliferation of the Internet, has significantly impacted tourism, attracting considerable academic attention in the last 25 years (Buhalis & Law, 2008; Amaro & Duarte, 2013; Pencarelli, 2020). The prior literature suggests that a growing `bifurcation´ among travellers significantly distinguishes those who have fully embraced the Internet from those who have not (Xiang et al., 2014).

In contrast, the study results illustrated that the sociodemographic profile of tourists in Burgos was the same regardless of their use of the Internet to search for information and to book or pay for some service. These unexpected results show that although the use of online distribution channels by tourists is important, tourists with a classic profile continue to coexist. Likewise, the similarity in the distributions of the variables considered allows us to check the robustness of the sample chosen in terms of tourist digitisation, considering both those who use digital media in their planning and those who do not. This fact makes it possible to reach conclusions based on tourists' diversity and take integrative measures based on their characteristics.

Many studies have shown that searching for information online and making reservations for tourism products has become widespread when tourists plan trips (Xue et al., 2021). The findings of this study provide further understanding in this field by revealing that 65% of respondents search for information online and 54% book or pay for any service online. Among these tourists, there was a high percentage of loyal tourists with high satisfaction levels. This may be because consumers are now more experienced and confident in using online tools, which is driving the change in decision-making patterns with new technologies.

The results of the ordinal regression analysis indicated that the use of the channels did not significantly influence the global satisfaction level. We found hardly any linkage between pre-trip internet usage and post-trip tourist satisfaction. These null results differ from previous expectations of a positive relationship that the literature takes for granted but has rarely been tested. Like the research conducted by Fernández-Herrero et al. (2017) and Ferrer-Rosell et al. (2017), this paper unexpectedly demonstrated that the relationship between ONDCs and overall trip satisfaction is extremely weak. Perhaps it may be the situation that evidence has indeed been found but not made public due to the lower likelihood of research reporting null results, those in which a commonly accepted theory finds no empirical support, will be written and published (Franco et al., 2014).

In contrast, binary logistic regression indicated that the use of ONDCs significantly influenced tourist loyalty. This finding, in line with those of Azis et al. (2020), confirmed that if tourists use the Internet to plan their trip, they are more likely to be loyal to the destination. Booking or paying online prior to the visit is a variable with a greater positive influence than seeking information on tourist loyalty. This may be because tourists know the destination because they have already visited it or it has been recommended to them. It should be noted that tourist loyalty to the destination is more difficult to achieve than overall consumer loyalty, so outstanding marketing strategies and efforts are needed.

On the other hand, a striking fact in the results is that although tourists' use of an ONDC has no significant effect on their satisfaction, it significantly affects their loyalty. However, many tourism studies have proven that tourists' satisfaction is an important antecedent of loyalty (Jeong & Kim, 2020; Li et al., 2021; Zheng, et al. 2021). This finding is considered one of the main theoretical implications, which, although out of the ordinary, shows cases where the same variable does not produce the same effect on tourist satisfaction and loyalty. Another example is the tourists' emotions variable. Although it is not a key element in the prediction of satisfaction, as shown in the study by Loureiro & Kastenholz (2011) that analysed rural tourism experiences in Portugal, it is a key element in loyalty, as shown by Muntean, Sorcaru & Manea (2023). In addition, it should be considered that other authors suggest that the relation between satisfaction and loyalty is not significant. Certain tourists may prefer to visit different destinations, although they assess the places they have visited positively (Albayrak & Caber, 2008; Faullant et al., 2008; Fyall, Callod & Edwards, 2003).

Currently, the restrictive measures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as border closures or the impossibility of travelling abroad, have led to the encouragement of tourism in the interior of each region, thus giving rise to the emergence of new tourist destinations such as those in the province of Burgos. These destinations are ideal for travel in pandemic situations, as they are quiet, close to nature and usually do not have crowds of tourists. They are also destinations that are in a rural environment with a limited presence on the Internet and with a non-professionalised tourism sector compared to more mature destinations. This translates into less destination-related or outdated content, fewer infomediaries including a new location in their databases, and fewer ratings or reviews from other travellers (Fernández-Herrero et al., 2017). Consequently, tourism agents who want to promote new destinations should be aware of these risks tourists face and try to be present and visible on internet webpages, blogs, tourist platforms, etc.

Regarding theoretical implications, in response to the scarcity of studies on the transformation of distribution channels, this paper conducts an empirical exploratory analysis considering tourists' behaviour and opinions. In addition, a theoretical model is created linking the use of online distribution channels in planning the visit with tourist satisfaction and loyalty, a relationship previously rarely studied in the literature. Controversially, this study shows how the same variable, the use of online channels, does not have the same significant effect on tourist satisfaction and loyalty. On the other hand, no studies have been found considering distribution channels' characteristics in relation to a context of depopulation and lack of digital connectivity.

This article focuses on a case study in the province of Burgos, whose inland rural destinations face the problem of depopulation. Finally, the obtained results may be controversial given the lack of studies that reinforce them. However, this study mainly contributes theoretically by considering different ways of planning the trip, offline and online, without presupposing the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty to more objectively know the tourists visiting a rural tourism destination.

6. Conclusions

This study aims to empirically determine the influence of tourists’ use of ONDCs in trip planning on their overall satisfaction level and their loyalty towards Burgos Province, Spain. In addition, the study investigates the difference between a digital tourist and a traditional tourist. In this way, this research allows the construction of a predictive mathematical model to estimate the likelihood that a tourist will be loyal towards the destination depending on whether ONDCs have been used.

The results of the research provide useful insights for tourism planners and decision-makers to shape the province’s digital marketing strategy by seeking to build an ONDC-friendly tourist destination. Considering the intensive use of ICTs and the changes in consumer habits in all sectors, few people visit Burgos and contract or pay for any service online, only 54%. Therefore, tourism decision-makers and organisations operating in this sector should apply internal marketing techniques to be present in ONDCs and give tourists useful and interesting information about the destination. Lack of trust, considered the biggest barrier for consumers shopping online, can be overcome if the seller's website conveys sufficient privacy and security (Cheung & Lee, 2006). In addition, it should be considered that with e-commerce and recent social commerce (transactions through social networks), users expect more from online businesses and put website credibility, compliance and nondeception first (De Matos, Curth & dos Santos, 2020). Therefore, expanding communication channels into the online environment must be accompanied by an image of trust that positively affects the attitude of potential customers (Abbasi et al., 2022).

These attempts can influence tourists' post-trip behaviour by facilitating their decision-making in preparation for their visit. Additionally, as information search is recognised as a vital part of the decision-making process and as independent booking experiences develop, the need for more travel and destination information is also growing. Travel agents should consider the Internet an important channel and update their company business models to meet market demand better. Improvements in ONDCs could make the difference between being chosen or not and the fact that a specific destination or business comes into the tourists' set of considerations as an alternative in the information search phase. Consequently, wider Internet use by the supply side will likely increase tourism demand over time, leading to more information-seeking, multichannel booking and higher tourist spending. In this way, destinations and tourism companies that take advantage of and encourage tourists' autonomy in organising their trip could gain a competitive advantage in the hypercompetitive marketplace.

In short, as the main practical implications, this work serves as a tool for tourism companies and institutions to make decisions about focusing their resources on those TDCs that achieve greater satisfaction and loyalty. Understanding new opportunities and threats within tourism distribution channels is essential for tourism professionals to remain competitive and successful. Marketing channels not only satisfy tourism demand by supplying goods and services of adequate quality and price but also increasingly stimulate demand by creating value for the user by generating benefits when accessing information and contracting a product through multiple channels (omnichannel).

Furthermore, developing effective strategies aimed at creating competitive advantages in the province of Burgos is a source of positive socioeconomic effects that help to tackle the demographic challenge that besieges rural destinations in this province, namely, depopulation.

Regardless of these conclusions, the study also has some research limitations. To extend the conclusions of this study, the particular characteristics of each tourist destination should be considered as a limitation. Further research on similar locations may help reinforce these results by increasing their generalizability and providing a comparative view of tourist behaviour. In addition, this study has analysed the satisfaction and loyalty of tourists at a specific point in time. A longitudinal investigation with samples from different years could provide more reliable results on the evolution of ONDC use for tourism planners and decision-makers. Likewise, due to the exploratory approach of the study and the subjective nature of the responses, as they are based on opinion surveys, the results should be interpreted with caution. To address this concern, some possible future lines of research can extend the scientific advances started in this work. For example, studies could be performed taking into account the use of platforms not only in planning but at all stages of the trip. The theoretical model can be extended by incorporating new dimensions, making it more robust and reliable. Another method that could be used is to analyse the use of online channels based on data from the web platforms themselves.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Society for the Development of the Province of Burgos, thanks to the collaboration agreement signed between the University of Burgos and this institution for the development of actions included in the Rural Strategic Plan of Burgos (PEBUR 15-20) in the fields of tourism, environmental economics and human capital and by the State Research Agency (Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain) and FEDER Funds (Knowledge Generation Projects) through the project "Methodologies for solving problems with economic, social and environmental criteria. Application to healthcare resource management" (ECOSOEN-HEALTH, grant ref. PID2022-139543OB-C44). The authors deeply appreciate the financial support received.