Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted various business sectors (Verma & Gustafsson, 2020), as most countries have taken strict measures to contain the pandemic. This impacted consumer practices, and thus, food purchasing and eating behaviour routines were readjusted. As a result, the hospitality industry faced challenges and problems that needed to be addressed (Gössling, Scott & Hall, 2021).

Research on the impact of crises, such as the Serve Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, the financial crisis in 2007 and the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020/2021, shows that the hospitality industry suffers significant damage from crises and takes more time to recover from them than other industries (Alonso-Almeida, Bremser & Llach, 2015; Davahli, Karwowski, Sonmez & Apostolopoulos, 2020; Gössling et al., 2021; Kim, Kim, Lee & Tang, 2020; Tse, So & Sin, 2006). Since an uncertain environment affects business strategies in the hospitality industry (Köseoglu, Topaloglu, Parnell & Lester, 2013), it is crucial to identify resilient business strategies to cope with a crisis (Gkoumas, 2022; O'Shea, Duarte Alonso, Kok & Vu, 2022). These business strategies can make a difference between insolvency and survival for an organisation within the hospitality ndustry.

Different groups of people at various decision-making levels influence the business strategies of an organisation. However, the operational managers are the ones who take action or not and minimise the impact of a crisis by implementing resilient business strategies (Doern, Williams & Vorley, 2019; Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd & Zhao, 2017). In addition, a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic can trigger new processes that ultimately lead to change and future growth (Chesbrough, 2020).

In line with prior research that identified perceived impacts, adaptive measures and adjustments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the hospitality industry (Bianchi, 2022; Kahveci, 2022; Madeira, Palrão & Mendes, 2021), we considered operational managers' viewpoints since these could be useful for the hospitality industry in terms of resilient business strategies and future responsiveness. As scholars emphasise (e.g., Coombs, 2015; Doern et al., 2019), managers are those within an organisation responsible for implementing crisis planning, management and response (Leta & Chan, 2021). Despite this high relevance and importance of managers in a crisis, there have only been a few empirical studies on crisis prevention and management by managers (Doern et al., 2019; Gkoumas, 2022; Kuckertz et al., 2020; Leta et al., 2021). Little evidence on the effectiveness of resilient business strategies in the hospitality industry on organisational survival and performance has been obtained (Hall, Safonov & Naderi Koupaei, 2023; Prayag, 2018). Furthermore, research has examined the actions, reactions and changes related to individual restaurants or individual sectors within the hospitality industry (Davahli et al., 2020; Gursoy & Chi, 2020), not considering the different sectors of the hospitality industry (Batat, 2021; Neise, Verfürth & Franz, 2021; Wu, Ku & Wu, 2023) and their possible different reactive business strategies to survive. The part of the literature that deals with hospitality-related resilience examines the hospitality industry in a tourism context (Hall et al., 2023) and does not distinguish between the tourism and hospitality industries (Ritchie & Jiang, 2021).

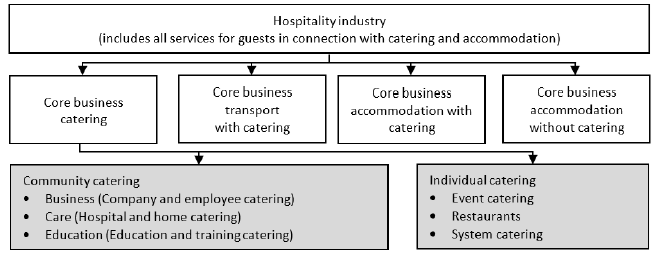

With the start of the first lockdown on March 20, 2020, in Germany, the COVID-19 pandemic came into focus. The hospitality industry was closed during the first lockdown, except for the care catering sector. This closure resulted in a massive impact on German society and businesses (Werking, Röckert, Schweers, Ruppenthal & Rückert-John, 2021), since the German hospitality industry is 'a catering service that is prepared outside the (own or third-party private household' (Steinel, 2008, p. 12). Each organisation in the hospitality industry had to consider what changes were needed during the lockdowns and in the future to survive. As can be seen in Figure 1, the German hospitality industry consists of four core business catering sectors, with a total of 186,597 organisations in 2021 employing 1 million people in 2022 (DEHOGA, 2023, pp. 5, 11): catering, transport with catering, accommodation with catering and accommodation without catering (Steinel, 2008). The core business catering is further divided into the two sectors of community and individual catering (Pfefferle, Hagspihl & Clausen, 2021; Steinel, 2008). In community catering, meals are prepared for a defined group of people in three different life situations (Steinel, 2008), the business sector with organisation and employee canteens, the care sector with canteens in hospitals, preventive care and rehabilitation clinics and retirement homes and the education sector with cafeterias in kindergartens, schools and universities (Pfefferle et al., 2021). In individual catering, meals are prepared for individuals or groups in three operational sectors: event catering, restaurants and system catering (Pfefferle et al., 2021). This study focuses on the core business catering with its two sectors, community and individual catering, as this sector represents the classic catering and hospitality industry (Roehl & Strassner, 2011), while the other three sectors only include catering in combination with transportation (core business transport with catering), accommodation (core business accommodation with catering) or without catering (core business accommodation without catering). The hospitality industry in Germany is the second most important sales channel for the food industry (BVE, 2022, p. 43). As it is one of the most important sectors in the German economy (BVE, 2022, p. 31), it is essential to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the entire hospitality industry, which this study aims to achieve. Furthermore, as stated above, the hostility industry is rarely investigated as a single industry (Ritchie et al., 2021). Figure 1 highlights in grey the two sectors, i.e., community and individual catering, investigated in this study.

Figure 1 Overview of the sectors of the hospitality industry in Germany. Source: own illustration based on Pfefferle et al., 2021.

This study focused on resilient business strategies operational managers applied in the German hospitality industry during the COVID-19 pandemic and its viability. Differences in the resilience of the hospitality industry sectors are also highlighted. This provides a holistic picture of the hospitality industry and contributes to advancing knowledge in the crisis management and resilience research field, as hospitality research was usually focused on single sectors or within the tourism industry context. Therefore, the aim of this study, which is exploratory, is threefold. First, the resilient business strategies that operational managers applied during the COVID-19 pandemic are identified. Second, it investigates which business strategies are considered future-resistant and viable. Third, future challenges in the hospitality industry are identified. Those organisations affected and those less affected can learn from this, consider these resilient business strategies and be guided by them in the future.

2. Literature review

2.1 Definition of crisis and crisis management

Several definitions of the term crisis exist in the literature, ultimately contributing to understanding the concept (Doern et al., 2019). Looking at the term from a management perspective, Pearson and Clair (1998, p. 66) defined crises as 'a low-probability, high-impact situation that t is perceived by critical stakeholders to threaten the viability of the organization'. This suggests that the organisation must respond to this threat to survive. Faulkner (2001, p. 136) went further in his definition and described the crisis as a situation 'where the root cause of an event is, to some extent, self-inflicted through such problems as inept management structures and practices or a failure to adapt to change'. According to this, management must take action to counter these problems.

Crisis management, in general, refers to the actions and communications systematically taken by the management to reduce the impact of a crisis (Leta et al., 2021). Although various crisis response models can be found in the literature (Ritchie, 2004), all recognised the crucial role of managers in a crisis (Bundy, Pfarrer, Short & Coombs, 2017; Burhan, Salam, Hamdan & Tariq, 2021; Coombs & Laufer, 2018; Ritchie, 2004). Crises often have negative consequences for the organisations, such as a decrease in demand and revenue, but at the same time, they can also provide possibilities for new business strategies, such as introducing new products and management programs (Okumus & Karamustafa, 2005). Gaining experience in a crisis and learning how to deal with it is an advantage for managers (Okumus et al., 2005) and, as such, needs to be investigated. To investigate crisis management, particularly within the hospitality industry (Burhan et al., 2021; Ritchie, 2004) and how managers handled the COVID-19 pandemic, this study focused on resilient business strategies applied by operational managers and their viability.

2.2 Business strategies within the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 pandemic

The literature shows that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted the hospitality industry's entrepreneurial activities (e.g., Kaushal & Srivastava, 2021; Verma et al., 2020). Various constraints, such as lockdowns, spacing regulations and capacity limitations, affected the financial viability (Brizek, Frash, McLeod & Patience, 2021; Gössling et al., 2021). In addition, the hospitality industry was one of the first to lay off employees in response to government-imposed lockdowns or was unable to keep employees permanently after reopening due to a decline in customer demand (Al-Ababneh, Al-Shakhsheer, Habiballah & Al-Badarneh, 2022; Baum, Mooney, Robinson & Solnet, 2020; Brizek et al., 2021). The market was additionally impacted by the limited availability of food and supply offerings (Rejeb, Rejeb & Keogh, 2020).

Already in the past, there have been global crises that had a significant impact on the hospitality industry and were overcome (Tse et al., 2006). However, the current crisis appears to be different, not least because of the lockdowns, which have never happened before. Therefore, in times of crisis, developing or changing business strategies is helpful (Bronner & De Hoog, 2014) as these impact an organisation performance (Sobaih, Elshaer, Hasanein & Abdelaziz, 2021). Targeted business planning, leadership, creativity and innovation of hospitality organisations have a significant impact on their performance (O'Shea et al., 2022; Sobaih et al., 2021; Wang, Wen, Liu, Gao & Madera, 2024). Operational managers are the ones who take action or not to mitigate the negative effects of a crisis (Williams et al., 2017) and to make significant contributions to new, innovative or changing business strategies (Doern et al., 2019).

For these reasons, alternative business strategies were and are necessary to stay in business. Frequently cited business strategies of the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 pandemic were hygienic measures, the use of new communication technologies and close relationships with external stakeholders (Gkoumas, 2022; Kahveci, 2022; Le & Phi, 2021; Schwaiger, Zehrer & Braun, 2022; Weidmann, Filep & Lovelock, 2023). Furthermore, managers implemented marketing strategies via social media or adopted apps and self-service technologies (Hemmington & Neill, 2022; Kuckertz et al., 2020; Madeira et al., 2021; Schwaiger et al., 2022; Wut, Xu & Wong, 2021). Employees were trained on hygiene concepts (Burhan et al., 2021; Le et al., 2021). These trainings were important and necessary tools to increase employees' knowledge of food safety and regain customer confidence (Bucak & Yiğit, 2021; Chou, Sam Liu & Lin, 2022; Colmekcioglu, Dineva & Lu, 2022; Kaushal et al., 2021). In addition, it was important for managers to retain employees despite the organisation's financial difficulties, as qualified personnel would be needed after the pandemic (Burhan et al., 2021; Chou et al., 2022). During the pandemic, restaurants also pursued cost-cutting strategies to reduce their fixed costs and introduced discounts, takeaway services and home delivery as alternative revenue streams (Burhan et al., 2021; Hemmington et al., 2022; Leta et al., 2021). Changes in menu planning due to rising costs resulted in shifts towards local food (Schwark, Tiberius & Fabro, 2020). Salary cuts instead of layoffs were also an option (Burhan et al., 2021). These examples show that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the hospitality industry implemented new and unconventional business strategies that can create opportunities for the future (Chesbrough, 2020; Kahveci, 2022; Richards, 2020).

2.3 Resilient business strategies in the hospitality industry and its viability

Crisis management aims to reduce the impact of crises, while resilience offers a complementary perspective on how organisations deal with adversities (Prayag, 2018; Zhang, Xie & Huang, 2024). Therefore, crisis management and resilience are interconnected (Prayag, 2018; Zhang et al., 2024). While crisis management is associated with changes resulting from extraordinary circumstances, resilience describes an organisation's ability to survive and thrive during and after a crisis (Holling, 1973; Vargo & Seville, 2011). Accordingly, a positive connection exists between resilience and the successful integration of crisis management and strategic planning in an organisation. In contrast to crisis management, however, resilience assumes that organisations can adapt to extraordinary circumstances, react to them and restore the previous state or even develop further (Barbhuiya & Chatterjee, 2023; Haimes, 2009; Lew, 2014). Resilience therefore offers a better perspective than crisis management in understanding how organisations deal with adversities (Prayag, 2018).

Resilience is related to change, but also to the stability and response of an organisation (Holling, 1973; Prayag, 2018). From a resilience perspective, an organisation in the hospitality industry must be able to organise itself in a crisis. The literature about the hospitality industry shows little evidence of the effectiveness of resilience business strategies on organisational survival and performance (Hall et al., 2023; Prayag, 2018). The focus of the literature is mainly on the tourism industry (Ghazi, Salem, Dar & Elbaz, 2024; Giousmpasoglou, Marinakou & Zopiatis, 2021; Hall et al., 2023; Lamhour, Safaa & Perkumienė, 2023; Zhang et al., 2024) and the part of the literature dealing with hospitality-related resilience examines the hospitality industry in a tourism context (Hall et al., 2023). Despite a growing interest in research about the resilience in the hospitality industry (Hall et al., 2023), there still is a need to address this research stream and focus exclusively on the hospitality industry, as previous research made no distinction between the tourism and hospitality industries, instead, the hospitality industry was usually equated with the tourism industry (Ritchie et al., 2021).

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience receives greater attention (Barbhuiya et al., 2023; Hall et al., 2023; Lee, Song, Yoon, Kim & Ham, 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). Organisational resilience looks at how organisations plan and adapt to the consequences of crises. It refers to an organisation's ability to take advantage of disruptive events threatening its survival through situation-specific responses and engagement in transformative business activities (Prayag, Spector, Orchiston & Chowdhury, 2020). As an essential characteristic of resilience, management should be a research interest in the literature, regardless of the industry or size of the organisation (Barasa, Mbau & Gilson, 2018; Prayag et al., 2020). Managers can react with their resilient business strategies positively to crises and influence and strengthen the resilience of employees and the organisation through their psychological resilience (Prayag et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024), mainly to face future crises. However, there has been little research on resilient business strategies implemented by gastronomy managers during a crisis and the industry's future challenges (Hall et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024).

3. Methodology

3.1 Research design

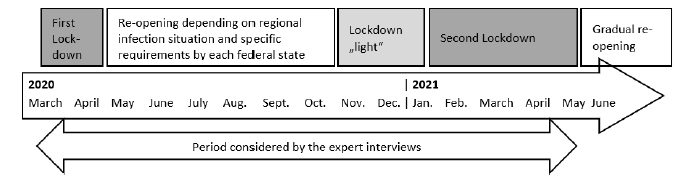

This study adopted a multiple-case study approach (Yin, 2018). This approach is best suited when theoretical knowledge is scarce and a complex, real-world phenomenon has to be investigated (Breier et al., 2021; Eisenhardt, 1989). The unit of analysis was the core business catering sector in Germany, with different cases from community and individual catering. The care sector, which was particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, was excluded to avoid placing an additional burden on decision-makers in this subsector. To gain an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon based on several cases and draw generalisable conclusions from the observations, a qualitative research design with semi-structured expert interviews was chosen. Qualitative research is well suited to understanding real-life situations and realistic events. Expert interviews are particularly suitable for this (Döring & Bortz, 2016) since they encourage the experts to share their experiences and personal opinions. Furthermore, expert interviews are a standard method in qualitative research (Döring & Bortz, 2016; Kaiser, 2014). The expert interviews were conducted as semi-structured interviews following the guidelines by Gläser & Laudel (2010, pp. 142-145) and the procedure given by Kaiser (2014, pp. 70-88) with three guiding questions: 1) What business strategies have been implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic? 2) Which business strategies became established, and why or why not? 3) Which of these business strategies do you think will last, and what business strategies do you think are future-resistant for the hospitality industry? The interviews covered the period from the first lockdown (March 20, 2020) to the end of the second lockdown (May 14, 2021). Figure 2 shows a simplified representation of the pandemic phases in Germany and the period considered for the interviews.

3.2 Sample, data collection, and analysis

The cases were selected using a purposive sampling method (Black, 2020). Selection criteria were: 1) it must be an organisation from the hospitality industry, 2) the organisations had to belong to the community or individual catering sector and 3) managers from the operational management level had to be willing to participate to ensure knowledge about and responsibility for the business strategies implemented. Purposive sampling is justified when experts are difficult to access, or their population is limited (Veal, 2018). The recruitment rounds for the interviews took place in March and April 2021. Experts were contacted via e-mail, and when they expressed interest, a more detailed telephone conversation was conducted. Twelve experts agreed to take part in the interviews. No financial incentives were offered for participation. Of these twelve experts, six were experts from community catering and six from individual catering. Before the interviews, each expert was asked to sign a consent form to take part in the interview. Table 1 provides an overview of the cases and interviewee profiles.

Table 1 Cases and expert interviewee profile

| Case | Sector | Position | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community catering: | |||

| E1 | Business | Managing Director | Male |

| E2 | Business | Vice President (Operative Managing Director) | Male |

| E6 | Business | Managing Director Department of Community Catering | Female |

| E3 | Education | Director Marketing | Female |

| E4 | Education | Managing Director | Male |

| E5 | Education | Unit Head | Female |

| Individual catering: | |||

| E7 | Event catering, Restaurant (Top Gastronomy) | Chairman, Managing Director | Male |

| E8 | Restaurant | Managing Director, Owner | Female |

| E9 | Restaurant | Managing Director, Owner | Male |

| E10 | Restaurant (Top Gastronomy) | Executive Chef | Male |

| E11 | Restaurant, Delivery service | Executive Chef | Male |

| E12 | System catering | Director Operations Excellence | Female |

Source: own elaboration.

Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the twelve interviews were conducted online using the Webex video conferencing tool between mid-April and mid-June 2021, audio recorded and transcribed verbatim according to the rules described by Rädiker and Kuckartz (2019). The interviews lasted between 40 and 68 minutes. All expert interviews were conducted and manually transcribed in German, resulting in 226 1.5-spaced A4 pages of transcripts. The authors translated the relevant text passages into English during data analysis. The total length of the interviews is 10 hours, 46 minutes and 18 seconds.

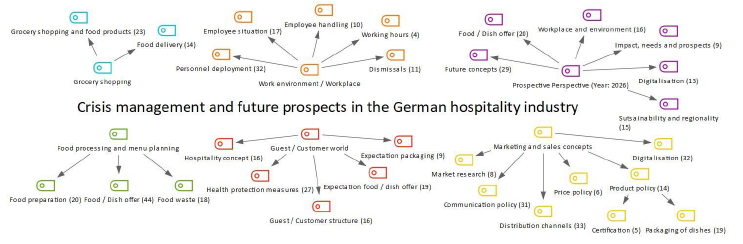

The authors analysed all interviews using qualitative content analysis, according to Mayring (2015). All interviews were coded within the case, followed by a cross-case analysis (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Yin, 2018). This approach allowed categories to be formed from the textual data as the cases were compared (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2022). MAXQDA software was used for coding and content analysis to conduct cross-case analysis and to support the interpretation of the qualitative data (Rädiker & Kuckartz, 2019). Reliability was improved by recoding or combining categories and omitting variables that did not meet the assumed criterion. Thus, reproducibility was the safest interpretation of reliability and was given (Krippendorff, 2004). Credibility, reliability and validity were established based on the data from the series of cases, discussions among the authors and verbatim quotations from the analysed text (Morse, Barrett, Mayan, Olson & Spiers, 2002). For the coding structure developed from the cases, see Figure 3.

4. Results

4.1 Grocery shopping

Planning processes in community catering had to be changed during the COVID-19 pandemic to have groceries available. In addition, alternative groceries had to be found, as certain ones could not always be ordered. Grocery purchases in the education sector came to a halt during the first lockdown, as facilities were either closed or only emergency childcare was available. E5: 'In some cases, grocery shopping came to a standstill because, of course, the facilities were closed. Day care and schools had some emergency care.'

In individual catering, there were supply bottlenecks, delivery delays and long waiting times, especially for groceries that did not come from Germany. E10: 'Everything that came from abroad was associated with a huge waiting time.' As regional groceries were available and affordable, purchasing was partly switched to regional products. E10: 'You had to go for absolute regionality.' Orders were placed with advance notice. E7: 'There were delivery delays; you had to be very forward looking and proactive and secure food through options.' To reach the minimum order value, larger quantities than necessary were ordered, and the order cycle was strategically adjusted. E9: 'We ordered twice. So once a week I have a bulk order and then I have to order again before the weekend, especially for fresh products.'

Concerning food availability, there was no uniform picture, neither in the sectors nor across. Some experts mentioned that fresh products were more difficult to order. E9: 'It was sometimes more difficult to get fresh products.' Others had no problems ordering fresh products but had more problems ordering dry products. E2: 'Bread, dry products, canned goods. For these products it was more difficult, but I would say with fresh products like vegetables, potatoes, salads, fruit, you didn't notice anything.'

All experts interviewed indicated that they approached their suppliers, exchanged information and sometimes even worked with them on a daily basis. E6: 'We have been very, very transparent with our suppliers from the beginning, in between on a daily basis, then again on a weekly basis.' For the entire hospitality industry, unpredictable changes in regulations and fluctuating guest numbers made grocery purchasing more difficult and required more risk-taking and flexible business responses. E7: 'So we had to look ahead and take even more risks.'

4.2 Food processing and menu planning

No major differences in food processing and menu planning were found between the hospitality industry sectors since all had to comply with hygienic standards and government regulations. All experts changed how they prepared and served food by adapting hygiene concepts, distance regulations and new work processes (e.g., Bianchi, 2022; Kahveci, 2022). E1: 'We introduced a hygiene concept and as much distance as possible between the chefs. The type of preparation has changed. In the past, for example, one chef did all the cooking for one dish, now, we have divided it up between different stations.'

The dish offered in community catering was reduced and simplified due to changes on site, e.g., due to lower guest numbers, higher product prices, unavailability of certain groceries. E4: 'The variety of food was kept simpler, more in the direction of practicability […] so two components, if possible, three at the most.' Menus were also reduced in individual catering for the reasons mentioned above.

To keep guests and win new ones, to-go menus were established in all sectors or expanded where they were already available. This led to the development of new business strategies, such as preserving food in jars or preparing it in transportable menu bowls. Menus were rethought, and associated changes, such as reorganising workflows, developing menu checklists or organising packaging and deliveries, had to be mastered.

Different results are found for newly developed dishes in and between sectors. In the business sector and at universities (education sector), plant-based menu lines were introduced as a supplement to existing vegetarian or vegan offerings. E6: 'We have always had vegetarian options anyway. Between 35 and 45 per cent of our range was vegetarian, but now we have launched a vegan food brand.' The situation was different in the education sector. Here, vegan dishes were less in demand and were not produced due to the high workload. E4: 'It is no longer asked for, and the effort is too high, so to speak, in normal times, if ten pupils wanted vegan, then of course we cooked ten portions. But if just one portion, maybe even just one per week is asked for, then we can no longer produce it.' Yet, the reduction to one dish meant that this was a vegetarian option. Regional products were increasingly used in individual catering.

In terms of food waste, little or nothing changed in the hospitality industry. The experts tried to extend the best-before date for unopened products. E12: 'We were able to talk to suppliers about food ingredients and apply for an official best-before-date extension.' The remaining stocks that could still be used were given to charity. E3: 'Leftovers were given to the Tafel [food bank] or to Caritas free of charge so that they did not end up in the dustbin.'

4.3 Work environment and workplace

As in previous crises, it was considered important to communicate with employees and inform them about the situation of the organisation (Gkoumas, 2022; Kahveci, 2022; Kuckertz et al., 2020; Schwaiger et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). E1: 'We have taken them on the journey. So, at the beginning it was clear, man, we have less revenue(s), the employees have to know and that we have to react.' The operational management faced employees' fears about possible job losses and health risks with regular team meetings, newsletters, training or similar (e.g., Bufquin, Park, Back, Souza Meira & Hight, 2021; Chou et al., 2022). E12: 'What we have learned in the last 24 months is how important it is in such a pandemic, […] is the communication with employees and guests. This was already important for us, but it has become more intensive with employees. We have to put in much more effort so that our employees feel informed and that their fears are taken away.'

In the German hospitality industry, most employees had to be sent on short-time work (Neise et al., 2021; Wilkesmann & Wilkesmann, 2021). The remaining employees were reorganised (e.g., into rotating teams), assigned new tasks and expected to be more flexible to get everything done despite short-time work and avoid infection chains. E1: 'The sales employees in our coffee bar were instructed to make the sandwiches now.' In system catering, employees were taken out of short-time work, and new employees (delivery drivers) were hired because of the introduced or further developed delivery services (Batat, 2021). E12: 'Of course, a whole new category of employees had to be hired, the delivery drivers. We have managed to motivate service employees to change to the delivery service.'

Employees worked short hours in all sectors, and tasks had to be redistributed. As a result, employee structures were strategically adjusted, and employment contracts were not renewed or concluded temporarily. Despite the lockdowns, the experts tried to keep the trainees employed and not put them on short-time work. This was done with strategic foresight so that the trainees could complete their training and have them available as skilled workers after the pandemic. E7: 'The trainees were able to complete their final examinations.'

4.4 Guest and customer world

Hygiene concepts and measures, food and occupational safety, and sensitivity to these were already integral parts of the hospitality industry (Tse et al., 2006). But since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, additional hygiene measures and concepts were introduced for protection reasons and since guests wanted to see hygiene and asked for it (Brizek et al., 2021; Elshaer, 2021; Ghazi et al., 2024; Kaushal et al., 2021; Weidmann et al., 2023; Yang, Liu & Chen, 2020).

New hospitality concepts were introduced in an attempt to strike a balance between hospitality and safety for the guests. A big challenge here was realising hospitality despite distance regulations and wearing masks (Elshaer, 2021; Giousmpasoglou et al., 2021). Before the pandemic, eating out was not only about eating well. Guests also wanted to communicate and switch off from everyday life. E9: 'The guest come to eat but also want to talk and that has gone.' According to experts from individual catering, the enjoyment and COVID-19 requirements can be reconciled. For this purpose, service training courses were conducted.

The experts from community catering were more critical of the compatibility of hospitality and COVID-19 pandemic requirements. The core function of community catering, dining with several people, was no longer possible or permitted. Thus, hospitality was no longer given. Especially in school canteens, the COVID-19 pandemic and enjoyment were not compatible. E4: 'Food is distributed, but no friendliness, no cosiness and no atmosphere.' To counteract this and to create a feeling of hospitality, the range of dishes was enriched with culinary contributions. E2: 'That is not hospitality at all at the moment. That's why you have to try to create a feeling of happiness with the culinary contribution. So that the people feel happiness arising while making the salad a little nicer.'

Sustainable packaging was important to guests and was demanded by them at the point of sale. During the pandemic, few sustainable packaging systems were available and affordable. As a result, the guests' high expectations for sustainable packaging systems could not be met. E4: 'The customers want more than what the market offers and what is affordable. […] It should be reusable or recyclable.'

Especially in community catering, it became clear that quality and culinary delights were an issue. The guests demanded more transparency about the origin of products. E5: 'We have a trend towards vegetarian and vegan food, especially among the younger generation.' There was an increasing demand for vegan and experimental food, such as insect food, especially in the educational sector. In addition, the demand for fast and comfort food such as burgers, fries and pizza increased in this sector. E3: 'I would say that it is noticeable that the students are demanding more sustainable offers than before. So, be it vegan or vegetarian. […] At the same time, there is also a demand for fast food and comfort food because it is food that creates security and also has somehow a feel-good factor.' In individual catering, there was a trend towards vegetarian dishes in some restaurants, while in others, the classics that were always on the menu were demanded.

4.5 Marketing and sales concepts

All experts looked for alternative sales and distribution channels. These ranged from to-go and takeaway to own delivery services, online ordering platforms and vehicle fleets (Batat, 2021; Breier et al., 2021; Hemmington et al., 2022; Neise et al., 2021; Zapata-Cuervo, Montes-Guerra & Jeong, 2021). Some experts focused on delivery services, as these fitted into their business concept. Others tried it and found that this business strategy was not practicable for them. All but one expert used their fleet with insurance upgrades if necessary for deliveries. Click and collect as well as click and delivery concepts were tested or already in use.

The experts named sales via vending machines, distribution stations with pre-ordering via digital portals or sales windows as further distribution channels. Some set up fast lanes for one-stop lunches. Here, guests could take meals with them for a whole day or several days with only one point of contact. This way, catering could be ensured at work and for the home office. E6: 'Often we did a fast lane (one-stop lunch), where it's about getting all food for the whole day. That means you go to the fast lane and pick up your big bag. There is a drink in there, a starter, a main course and another snack for the afternoon. […] We've developed a new concept. If I go to the office on Wednesday and I know I will be working from home on Thursday and Friday, I can pick up a box on Wednesday afternoon that contains everything for one, two, three, four, whatever days in the home office.' The purchase and use of food trucks in the education sector was mentioned as another sales and distribution channel.

Digital forms were increasingly used in the hospitality industry as marketing and sales strategies. The organisation's homepages played an important role, and social media channels were also increasingly used. Online shops were also set up, and apps were introduced. E8: 'Yes, I am going towards an online shop.'

In terms of communication policy, there was also a uniform picture across all sectors. Advertising was carried out via classic media tools such as flyers in letterboxes, direct mailings, inserts in daily newspapers at the weekend, bulletin boards in the street, poster advertising and notice boards. The experts also relied on their homepage, intranet, apps and social media channels such as Facebook (now Meta), Instagram and Twitter. Besides, newsletters were sent via e-mail to customers from the customer file. Special promotions and marketing measures took place on Christmas, Easter, Mother's Day, Father's Day and Valentine's Day. Progressive digitisation can be observed in the entire hospitality industry (Elshaer, 2021; Ghazi et al., 2024; Kaushal et al., 2021). Homepages and social media accounts were used more, and posts were shared more than before the pandemic. E8: 'We try to continue feeding through our Facebook posts.' For homepages, the current menu needed to be available. E9: 'People first look at the homepage and menu of the restaurants to see what's on offer. The medium homepage has become more established in restaurants.' One expert used an influencer to promote takeaway or delivery food boxes. E11: 'We of course write to bloggers, write to the press, supply press and bloggers.'

The experts were rather cautious in explaining their price policy. Yet, promotions were carried out to attract customers, such as monthly cards with price points or masks given away. To-go food boxes were offered cheaper than eating in the restaurant. Different price categories were offered for various customer groups. The few mentions indicated that the hospitality industry had little room for manoeuvre on prices, regardless of the sector.

In terms of product policy, the main focus was on packaging and adapting the meals to containers. At the beginning of the pandemic, getting any packaging was difficult. The experts developed various business strategies out of this need but also with sustainability in mind. E11: 'We are developing a concept where we can offer a more reusable solution.' In community catering, reusable solutions were introduced via deposit systems in conjunction with an app. In individual catering, single-use systems with sustainable packaging material were more common.

4.6 Prospective Perspectives

The hospitality industry has to become more professional, particularly in operational management, dealing with employees and digital know-how (Batat, 2021; Brizek et al., 2021; Elshaer, 2021; Hemmington et al., 2022; Zapata-Cuervo et al., 2021). All experts were in favour of introducing or maintaining delivery services as viable future business strategies (Brizek et al., 2021; Elshaer, 2021; Hemmington et al., 2022; Kaushal et al., 2021; Neise et al., 2021; Zapata-Cuervo et al., 2021). To be competitive and to be able to meet guest demands, digital concepts must be further developed. The independent compilation of meals by the guests and digital tracking of the order, preparation, and delivery processes are under consideration in specific sectors. There will be business strategies where guests can place digital orders in the facilities via tablets and create their dishes. Pagers will then inform them that they can pick up their food or drinks at self-service counters. Despite digital support, more work and flexibility will be demanded of the employees, as fewer employees will be available and more work must be done. Opening hours in the hospitality industry will be adjusted. E8: 'And when the crisis is over, I won't be open six days a week.'

The wishes of the guests must be better understood and fulfilled. In the future, healthy and sustainable food will also play a role for small budgets. Opportunities must be created for guests working from home to be catered by community catering. The experts in business catering assumed that guest numbers would decline due to home office. The delivery and to-go concepts in the form of multi-day boxes, cooking boxes and preserving jars could be business strategies to provide dishes to guests beyond canteen opening hours. E1: 'What we are going to do is that we go more on this kind of provision of products […] that you can take away and prepare yourself in community.'

According to all experts, the cooking profession must be promoted. Training will be essential to meet the guests' quality expectations (Chou et al., 2022). This includes chefs incorporating future trends such as health-oriented nutrition, vegetarian and vegan cuisine, seasonal and regional cuisine and product transparency into their business strategies. E5: 'This development will definitely continue. I put more value on the products, in the area of ecology, but also animal welfare, and things like that. […] Regionality will again play a greater role.' For community catering, it will be particularly important to consider reducing the carbon dioxide footprint and avoiding food waste. E3: 'So then the topic of sustainability will be much more in the focus than it is now, as well as the topic of climate protection.' The experts also mentioned that the price level will be adjusted upwards. E7: 'We have an increase in the cost of living […] and our industry will also have to raise prices.'

5. Discussion

This study contributes to ongoing research regarding the COVID-19 pandemic in the hospitality industry. First, the results contribute to the literature on crisis management and resilience in the hospitality industry. Although researchers have investigated crises in the past and the COVID-19 pandemic recently, knowledge of how managers in the hospitality industry face crises, particularly in terms of resilience, is still limited (Kuckertz et al., 2020). In particular, little evidence has been obtained on the effectiveness of resilient business strategies in the hospitality industry on organisational survival and performance(Hall et al., 2023; Prayag, 2018; Sobaih et al., 2021). The results show that the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated restrictions affected some hospitality sectors more and others less. Those who developed resilient business strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic and were open to forms of digitisation, survived and continued their businesses (Barbhuiya et al., 2023; Ghazi et al., 2024; Giousmpasoglou et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024). An orientation of the dish offered towards regional, vegetarian, or vegan products seems to have a promising future prospective. In addition, the focus should also be on out-of-house meals such as food boxes, jars or alike, including delivery services. Sustainable forms of packaging must be provided for this. Looking at human resources, the entire hospitality industry is already facing major challenges, even more so in the future (Bufquin et al., 2021; Chou et al., 2022). Skilled workers look for crisis-proof jobs, fixed working hours and free weekends and thus, leave the hospitality industry. The experts doubted that the temporary workers would return, not least because of the payment. The developments and possible uses of forms of digitisation could at least counteract the shortage of employees to a small extent. Nevertheless, the hospitality industry must become attractive again for employees to survive (Al-Ababneh et al., 2022), and managers must communicate with them regularly (Schwaiger et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). Second, this study examined individual and community catering in the German hospitality industry and compared both core business catering sectors with each other. This allowed differences and similarities between the sectors to be identified. To our knowledge, this is unique as previous studies focused on single sectors, for example, restaurants or star cuisine (Batat, 2021; Neise et al., 2021) or examined the hospitality industry in a tourism context (Hall et al., 2023; Ritchie et al., 2021). Third, this study shows that the hospitality industry is viable and future-resistant despite the difficulties it faces, but it requires rethinking and resilient business strategies (see Table 2) (Davahli et al., 2020; Giousmpasoglou et al., 2021; Gkoumas, 2022; Lee et al., 2024; O'Shea et al., 2022; Weidmann et al., 2023).

Table 2 Resilient business strategies within the hospitality industry

| Subject areas | Resilient business strategies within the hospitality industry |

|---|---|

| Grocery shopping | Adjustments of planning and ordering cycles Search for substitute products Switch to regional products Close collaboration with stakeholders |

| Food processing and menu planning | Hygiene measures and concepts Changes in working processes Focus on to-go and takeaway Recipe changes Introduction of plant-based menus Offerings of vegetarian, vegan, regional or comfort food Reduced variety and choices Extension of best-before-dates Distribution to charities Menus in food jars |

| Work environment and workplace | Communication with and information of employees Regular team meetings Training programs for employees Short-time work, layoffs, no renewal of work contracts Redistribution of tasks to employees Flexible deployment of employees |

| Guest and customer world | Hygiene measures and concepts Hospitality concepts Service training Sustainable packaging systems Transparency towards customers |

| Marketing and sales concept | Redesign of marketing strategies To-go services and boxes Delivery services (with or without own fleet/employees) Online- and pre-ordering Online-shops Click and collect, click and delivery Vending machines and food trucks Fast lanes for one-stop lunches Use of digital tools, print media, food blogger and influencer Special promotions and discounts Guest surveys Reusable solutions of packaging (with deposit systems) |

| Prospective perspectives | Professional operational management Delivery and to-go services Digital know-how and concepts, e.g., digital order, order and delivery tracking Automation in the hospitality industry Decreasing the number of employees Flexibility of employees Hospitality concepts Adjustment of opening hours (shortened) Offer of healthy and sustainable food/menus Regional cuisine Food concepts for guests in home office Transparency of processed products Avoidance of food waste Reduction of carbon dioxide footprint Increases in prices Promoting the profession |

Source: own elaboration.

6. Conclusions and implications

6.1 Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the German hospitality industry to find out which resilient business strategies operational managers applied during the COVID-19 pandemic and which are considered viable for the future. Differences in the resilience of the hospitality industry sectors are also highlighted. Furthermore, the challenges of the hospitality industry are identified. The results of the study show diverse resilient business strategies within six areas (grocery shopping, food processing and menu planning, work environment and workplace, guest and customer world, marketing and sales concepts and under prospective perspectives) that operational managers in the hospitality industry responded to the crisis in a situation- and organisation-specific manner and implemented transformative business activities. These results provide a holistic picture of the hospitality industry and contribute to advancing knowledge in the crisis management and resilience research field, which could thus serve as a blueprint for the hospitality industry.

6.2 Practical implications

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic challenges previous business strategies related to the resilience of hospitality organisations. As this research shows, organisations in the hospitality industry developed and implemented resilient business strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic to survive and be viable in the future. However, the organisations did not always follow the same business strategies; these were partly hospitality sector-specific and shaped by the organisation itself. In addition, some organisations did not consider or were unable to implement resilient business strategies. In conclusion, each organisation must consider and evaluate which business strategies may be crisis-resistant and viable for them in the future to ensure resilience. In this context, it is important to consider whether the strategies introduced in the short term can also be viable in the long term. If not, which business strategies would be more crisis-resistant in the future. Concerning the business strategies of our sample, it should be noted that short-term measures were necessary. However, in the long term, to sustain or gain competitive advantages and minimise risk, reasonable payment and training of employees, innovation linked to digitisation and sustainability and diversification strategies such as preparation of food offerings and services seem advisable.

6.3 Limitations and future research

The results of this study and the conclusions were drawn on a small sample and a single country of study. Hence, the identified resilient business strategies cannot simply be generalised and applied to other industries or the rest of the world. As other studies have examined resilient business strategies for other industries or countries, this study complements them and identifies further possible resilient business strategies with a holistic picture of the hospitality industry. As the hospitality industry is severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, further studies need to be conducted on the challenges, the resilient business strategies put in place, and the ones that follow. To this end, research must also address the individual sectors of the hospitality industry. In addition, it must be researched which resilient business strategies are viable for the future, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, to be resilient to possible future crises. In order to provide worldwide knowledge for practice, it would be essential for future research to compare the results between regions and countries as well as the different sectors of the hospitality industry to reveal more and maybe other resilient business strategies with different resources employed.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support by the university-internal research and development funding of Hochschule Fulda - University of Applied Sciences.