Introduction

Destination image emerges as an important phenomenon to see tourism's economic effects in destinations (Uslu & Inanır, 2020). Destination image affects tourists’ destination perceptions and destination choice. Tourists create the destination image by choosing different information sources (Cooper & Hall, 2023). A positive image in the minds of tourists makes them intend to revisit destinations (Atmari & Putri, 2021). However, another reason why tourists visit destinations is due to their previous cultural heritage tourism experiences. The surge in demand for cultural heritage tourism has garnered increasing attention from scholars in recent years (Kempiak et al., 2017; Nguyen & Cheung, 2015), leading to numerous studies aiming to reveal the behavioural attitudes of tourists in this context (Alrawadieh et al., 2019; Wu & Li, 2017). Authenticity and involvement stand out as essential factors shaping tourist behaviours and perceptions.

Researchers have long emphasised the vital role of authenticity in cultural heritage tourism, suggesting that tourists seek authentic experiences to attain self-actualisation and a sense of well-being (Kolar & Zabkar, 2010). Consequently, the importance of authenticity in enhancing the quality of cultural heritage tourism is widely acknowledged (Lu et al., 2015; Ram et al., 2016). Studies have consistently shown a positive correlation between increasing demand and satisfying customer experiences in cultural heritage

tourism (Brodie et al., 2011; Higgins & Scholer, 2009), influencing tourists’ perceptions regarding destination image. Yet, further research is needed to explore the effects of tourists’ involvement levels on shaping a positive destination image.

This research aims to analyse the effects of authenticity and involvement on destination image, shedding light on tourists’ perceptions. Destination image components, including infrastructure, socio-economic environment, natural and cultural resources, atmosphere, and overall image, are conceptualised for examination. Thus, destination image can be expressed as an attitudinal structure consisting of intellectual/perceptual, sensory and general image, which is a total summary of the ideas, beliefs and impressions that people have towards a certain area (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Stylidis, 2016). Destination image can be the visitor’s objective perception of the reality of the destination (Chen & Tsai, 2007). The study was conducted in Side, located in Antalya, an internationally renowned beach heritage destination. Side boasts significant historical sites and natural wonders such as sandy beaches, coastal forests, rivers, and archaeological sites. However, rapid and unplanned development since the 1990s has led to concerns about damage to archaeological sites and landscapes (Gezici, 2006; Brodie et al., 2011). Consequently, the study’s findings offer practical insights to local administrations to develop sustainable tourism policies and stakeholders to better understand tourists’ needs and preferences.

Literature framework and hypotheses

Effects of authenticity on destination image

Cultural heritage tourism is linked to authenticity, offering well-preserved historical and traditional experiences (Belhassen et al., 2008; Park et al., 2019). Extensive research in the literature indicates authenticity as a central characteristic and primary motivation in cultural heritage tourism, facilitating tourists’ connection with destinations (Lindberg et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2015). The main idea is that tourists’ authenticity needs towards an object are formed in advance by internal or external factors, and the residents can provide tourism activities and products that meet their imagination and needs, which means co-creating authentic tourism experiences with tourists (Zu et al., 2024).

Visitors actively seek authentic experiences in cultural heritage destinations, indicating a strong desire for genuine encounters (Viljoen & Henama, 2017). Satisfied tourists’ interest in authentic experiences significantly enhances the quality of cultural heritage tourism, thereby creating a positive destination image (Lu et al., 2015; Ram et al., 2016). Researchers consistently conclude that authenticity plays a primordial function in shaping a positive destination image (Frost, 2006; Park et al., 2019). Based on this rationale, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Authenticity positively and significantly impacts destination image.

Effects of involvement on destination image

Involvement is a noticeable construct in the tourism and marketing fields due to its recognised power to explain and predict changes in the behaviour and attitudes of tourists (Campos et al., 2017). Involvement may be felt towards an activity, a product, an issue, an advertisement, a situation or a decision (Bezençon & Blili, 2010). Thus, involvement, defined as the motivation or willingness to engage in an activity, is crucial in tourism (Gursoy & Gavcar, 2003).

Earlier studies have mainly focused on the involvement of the tourists’ (Campos et al., 2017; Hou et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2015) and destinations’ residents' perspectives (Aleshinloye et al., 2021; Erul et al., 2023; Erul et al., 2024) in tourism literature. For instance, tourists’ levels of involvement significantly influence their perceptions of destination image, with higher involvement correlating with more positive destination image perceptions (Lin & Chen, 2006). Chon (1991) suggests that tourist involvement directly influences tourist experience, positively affecting destination image perceptions. Hou, Lin, and Morais (2005) also find a positive relationship between tourist involvement in cultural heritage tourism and perceptions of destination image. Therefore, it stands to reason that active involvement in tourism activities positively influences destination image perceptions. Numerous studies support this notion, highlighting a positive correlation between involvement and destination image (Lu et al., 2015; Prayag & Ryan, 2012; Kutlu & Ayyıldız, 2021). Consequently, the following hypothesis is posited:

H2: Involvement positively and significantly impacts destination image.

Effects of destination image on satisfaction

The image concept holds significant relevance in marketing and behavioural sciences, representing individuals’ perceptions of products, objects, and events driven by beliefs, feelings, and impressions (Crompton, 1979). In the context of tourism destination marketing, destination image has emerged as a crucial indicator of branding success, representing individuals’ impressions, opinions, expectations, and emotional associations with a place (Tasci et al., 2022; Uslu et al., 2020). Conceptualised with tangible and intangible dimensions, destination image encompasses infrastructure, socio-economic environment, natural and cultural resources, atmosphere, and overall characteristics (Zhang et al., 2014).

The concept of destination image, first introduced by Hunt (1971), is expressed as the sum of visitors’ thoughts, beliefs, ideas, impressions or feelings about destinations. Afterwards, Gartner’s (1993) framework conceptualises destination image as having three hierarchical components: cognitive, affective, and conative. Cognitive image reflects individuals’ beliefs and knowledge regarding destination characteristics, affective image pertains to emotional reactions or evaluations influencing destination choice, and conative image represents active tourist evaluation of a potential holiday destination (Gartner, 1993). According to Echtner and Ritchie (1993), destination image consists of feature-based and holistic structures. It is stated that each of these features includes functional and psychological features. Destination images can vary from those based on common functional and psychological characteristics to more distinctive or even unique features, events, emotions or auras. Previous research highlights a direct effect of destination image on tourist satisfaction (Lee & Xue, 2020; Kutlu & Ayyıldız, 2021; Tasci et al., 2022). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Destination image positively and significantly impacts satisfaction

Effects of experience quality on satisfaction

Experience quality, as perceived by tourism stakeholders, refers to the psychological and subjective evaluation of benefits gained from the tourism experience (Rehman et al., 2023). Research indicates that the benefits derived from the tourism experience influence tourist satisfaction (Altunel & Erkurt, 2015; Domínguez-Quintero et al., 2019). Examination of experience quality elucidates tourists’ satisfaction during tourism activities, emotions, loyalty, and behavioural intentions, as it may impact these factors (Domínguez-Quintero et al., 2019; Mansour & Ariffin, 2016). Numerous studies demonstrate a positive and meaningful relationship between experience quality and satisfaction (Altunel & Erkut, 2015; Parreira et al., 2021). According to Tiwari et al. (2023), enhancing tourism experience should focus on human emotions such as joy, love, and positive surprise.

In a similar vein, scholars have explored experience quality using various dimensions. For instance, Kao et al. (2008) and Jin et al. (2016) studied it with immersion, surprise, involvement, and fun, while Cole and Scott (2004) identified entertainment, education, and community as dimensions of exhibition experience quality. However, Altunel and Erkut (2015) assessed experience quality with the dimensions of escape, learning, enjoyment, fear and displeasure. Consequently, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H4a: Experience quality positively and significantly impacts satisfaction

Effects of experience quality on re-patronage intentions, word-of-mouth and willingness to pay more

High-quality experiences serve as potent predictors of tourists’ behavioural intentions. Tourists’ behavioural intention, defined as their perceptions of expectations regarding what to do in a specific situation, influences their decisions and actions (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2000). Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) emerges as a trusted source of information regarding tourists’ intentions to revisit based on their positive travel memories, which drive their inclination towards revisiting (Ali et al., 2016; Coudounaris & Sthapit, 2017; Tung & My, 2023). Given the role of experience quality in shaping these positive memories, it is plausible to suggest that revisiting intentions are also influenced (Ha & Jang, 2010; Lee et al., 2012). Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4b: Experience quality positively and significantly impacts re-patronage intentions.

Word-of-mouth (WOM) communication holds significant sway in the tourism industry, with both positive and negative effects observed across various types of tourism. Tourists often convey their thoughts and experiences through WOM, which serves as a crucial predictor of their behaviours (Calvo-Porral et al., 2017). Given that tourists who experience high-quality experiences in cultural heritage tourism are likely to become advocates for the destinations they visit, it is imperative to understand how experience quality influences WOM. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4c: Experience quality positively and significantly impacts word-of-mouth.

Tourists often perceive a relationship between price and quality, with higher prices often associated with higher quality, indicating prestige (Wiedmann et al., 2009). This perception may motivate tourists to be willing to pay more for better-quality experiences (O’Cass & Frost, 2002). Therefore, it is likely that experiencing better-quality experiences would positively influence tourists’ willingness to pay more. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4d: Experience quality positively and significantly impacts willingness to pay more.

Effects of satisfaction on re-patronage intentions, word-of-mouth and willingness to pay more

Satisfaction is a critical parameter for measuring the overall perceived performance of a tourism experience (Yoon & Uysal, 2005). It encompasses individuals’ expectations before travel experiences and their perceived performance afterwards (Chen & Chen, 2010). Tourist satisfaction is a pivotal factor in revisiting intentions, as evidenced by previous studies on destination loyalty (Cong, 2016; Cong & Dam, 2017; Luvsandavaajav et al., 2022). Moreover, positive word-of-mouth communication and recommendations from tourists contribute significantly to increasing potential visitor numbers and destination appeal (Kozak & Beaman, 2006; Santos et al., 2013). Additionally, tourists are often willing to pay more for nature conservation, sustainable destinations, climate change mitigation, and overall quality improvement and development in destination experiences (Mgxekwa et al., 2019). Considering the positive and meaningful correlation between satisfaction and behavioural intentions observed in previous studies (García- Madariaga et al., 2022; Nam et al., 2011), the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a: Satisfaction positively and significantly impacts re-patronage intentions. H5b: Satisfaction positively and significantly impacts word-of-mouth.

H5c: Satisfaction positively and significantly impacts willingness to pay more

Methodology

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research transforms data obtained from participants with specific measurement tools into generalisable and universal information using various statistical analyses. Hence, quantitative research has a nature that requires evidence-seeking identity and working on large sample groups (Baltacı, 2019).

Since the most appropriate way of working for the purposes of the study is to perform analyses using hypothesis testing techniques, a quantitative research approach based on the positivist paradigm was adopted. Data was analysed using statistical methods, and the significance of the relevant effects was revealed and it was decided to accept or reject the hypotheses.

Proposed Model

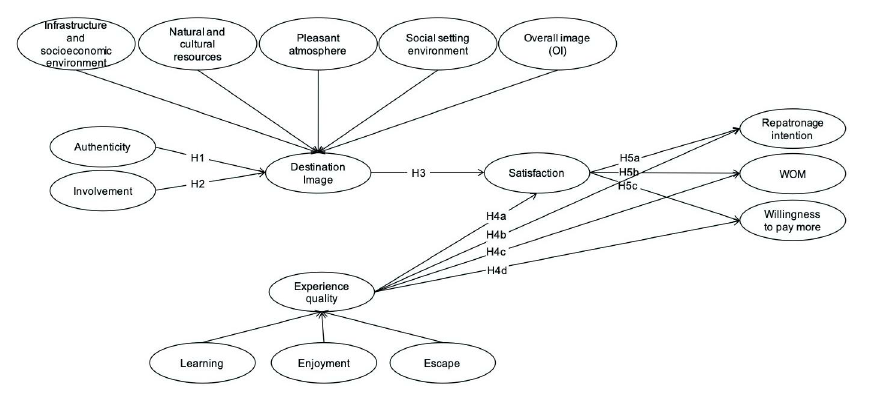

This study examines the effects of authenticity and involvement on destination image. Additionally, it investigates the effects of experience quality and destination image on satisfaction, repatronage intention, WOM, and willingness to pay more. Therefore the proposed model of the study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Data collection and analysis

Questionnaires were administered in Side, either in English or Turkish, depending on the origin of the participants. Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews, as this technique has been shown to yield a high response rate (Xu & Fox, 2014). Quota sampling was employed based on the population characteristics of Side’s tourist profile (see Table 1). The questionnaire administration took place from the 1st of June to the 1st of November 2019. In total, 394 valid questionnaires were collected. The model tests the relationships depicted in Figure 1. Data were analysed using SPSS 27.0 for descriptive analyses and Smart PLS 3.2.2 statistical programs with PLS-SEM. Descriptive statistical analysis, reliability and validity analysis, PLS-SEM analysis were performed for this study.

Measures

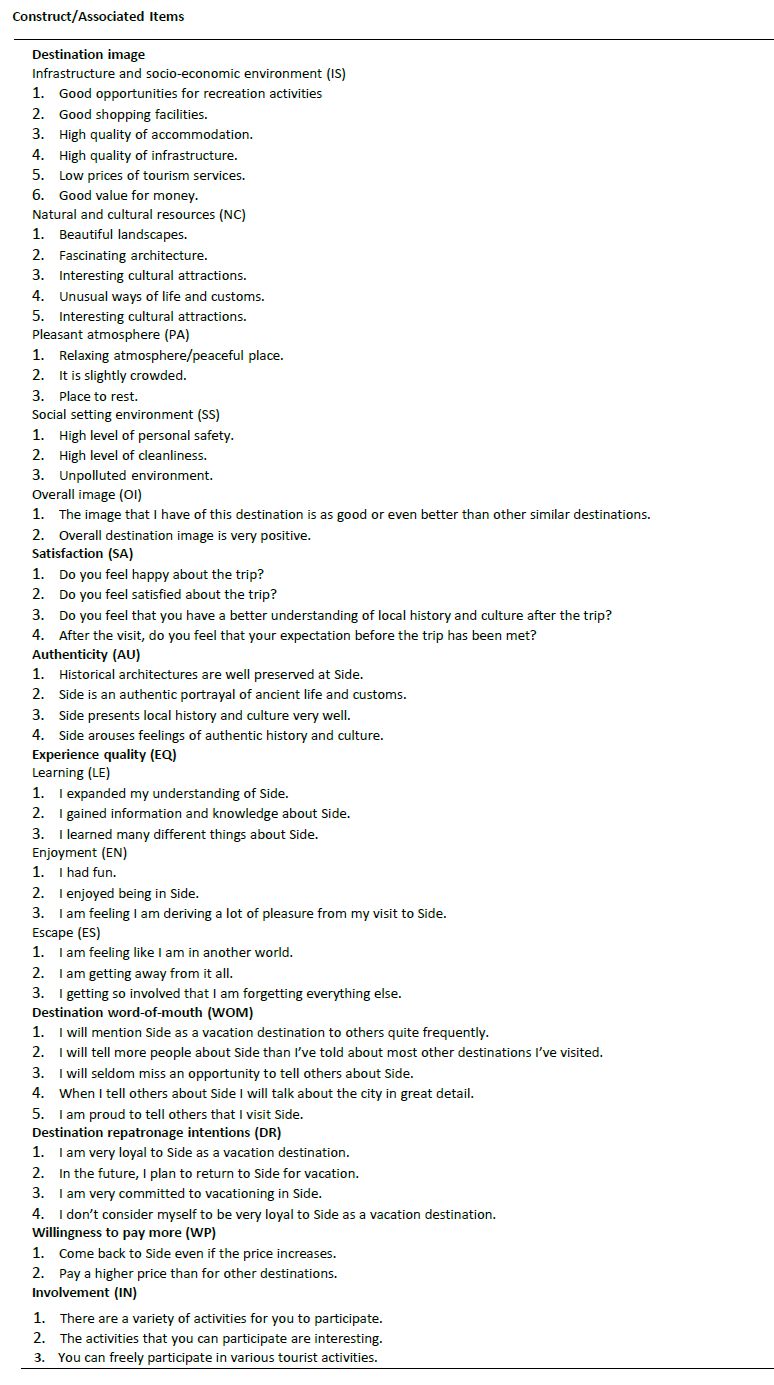

The scale items were adopted from prior studies and rated on a seven-point Likert scale (see Table 1). Destination image was adapted from García et al. (2012). Authenticity, involvement, and satisfaction were assessed using Lu et al.’s (2015) scale. Experience quality was operationalised using the three first-order dimensions: enjoyment, escape, and learning, proposed by Altunel and Erkut (2015). Word-of-mouth and re-patronage intentions were measured using Sirakaya-Turk et al.’s scale (2015). Willingness to pay more was adapted from Bigné et al. (2008).

Findings

Profile of participants

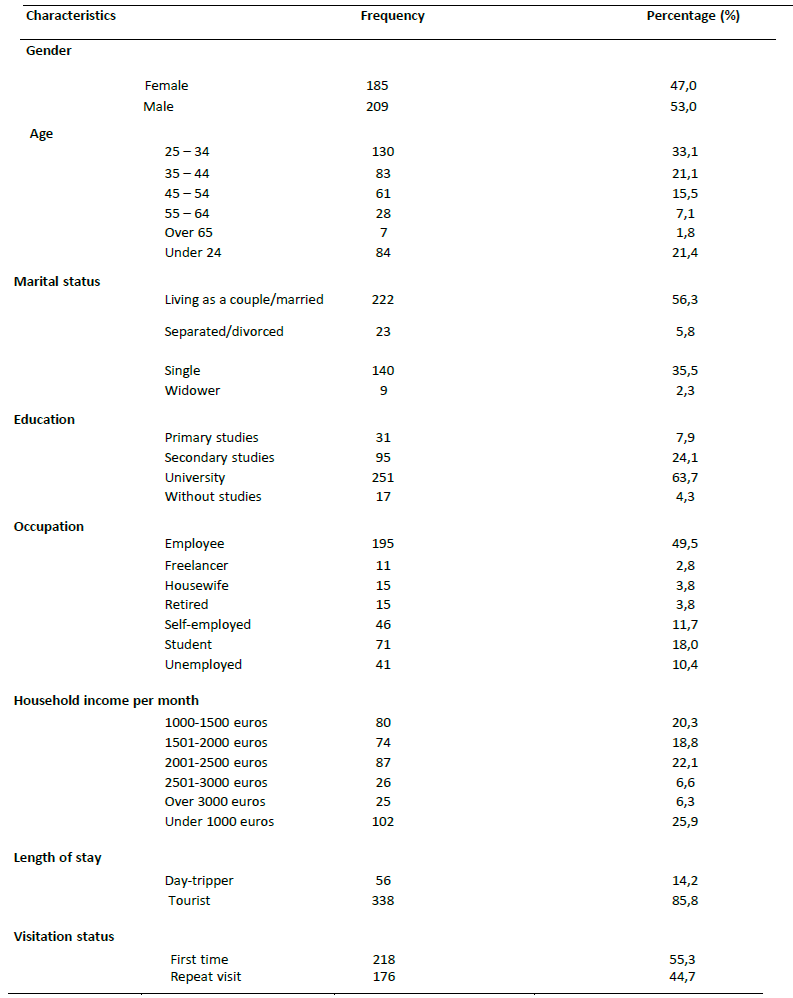

As seen in Table 2, the demographics of the 397 participants were mostly male (53.00%) and aged 25-34 years (33.10%). 56.3% of the participants stated that they are living as a couple or married. According to education level, most participants (63.7%) graduated from university. Half of the participants (%49.5) are employees. Related to household income per month, most of the participants were under 1.000 Euros. Roughly most of the participants were first-time visitors (55.3%). Lastly, most participants were tourists (85.8%) except day-trippers.

Reliability and validity evaluation of the proposed model

The proposed model was computed using PLS-SEM in SmartPLS software 3.3.2, as preliminary tests on the sample indicated non- normal data. PLS-SEM is less stringent when working with this data type (Hair et al., 2014). The two-stage approach was employed to evaluate the second-order constructs (Hair et al., 2014).

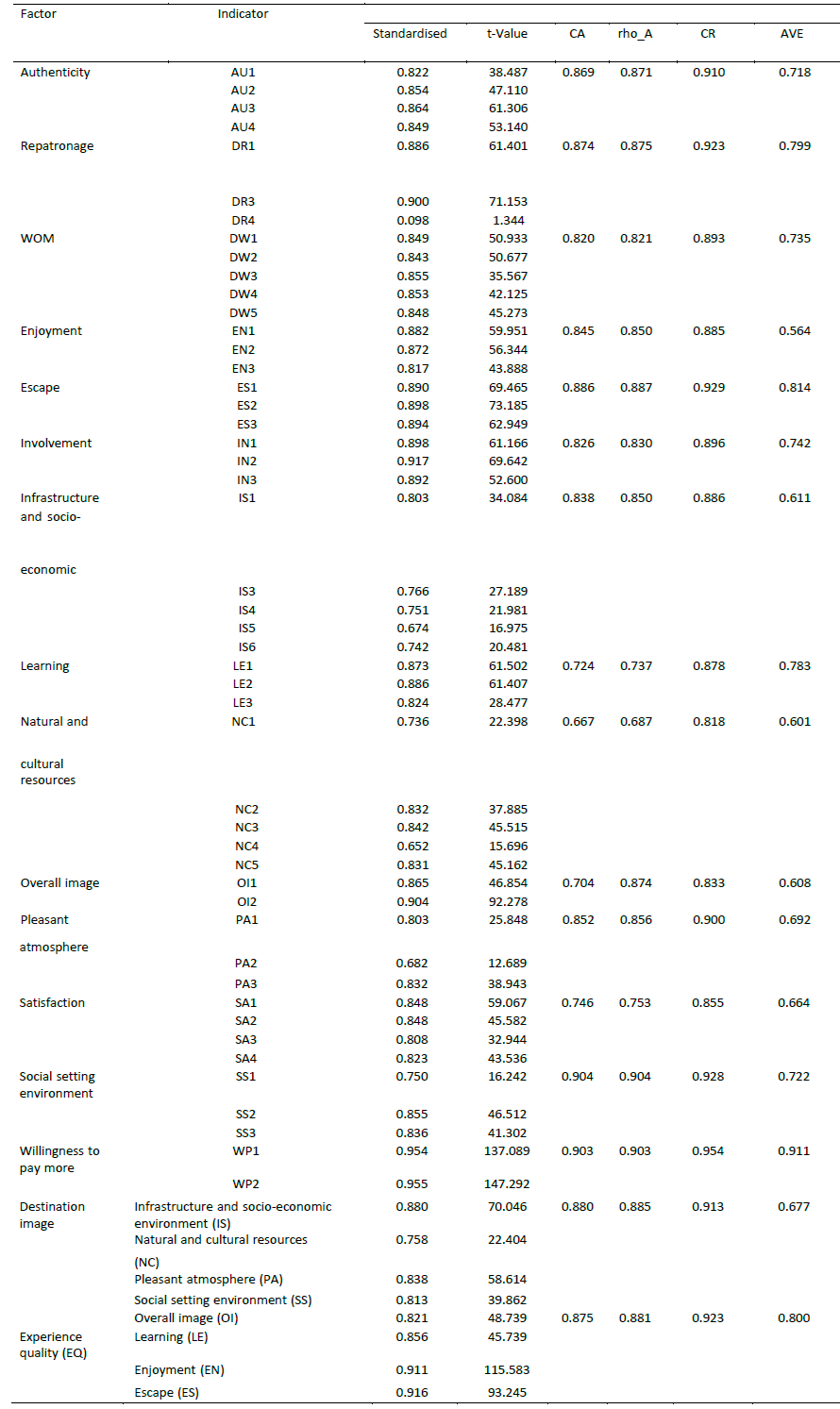

Indicator reliability was assessed, with meaningful standardised loadings higher than .70. Internal consistency reliability was evaluated using Composite Reliability (CR), with values higher than .70 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). Convergent validity was examined through Average Variance Extracted (AVE), with values higher than .50 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988).

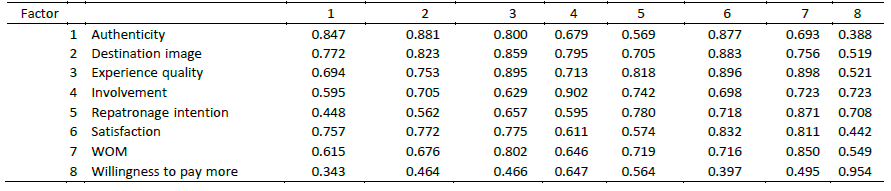

Discriminant validity was established by ensuring that each construct’s AVE was greater than its squared correlation with any other construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) ratio was also calculated to determine discriminant validity, with every indicator below .85 (Henseler et al., 2014). Tables 3 and 4 display the proposed model's favourable reliability and validity properties.

Table 3 Reliability and convergent validity of the final measurement model

Note: All loadings are significant at p < .01 level. CA = Cronbach’s alpha; CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted.

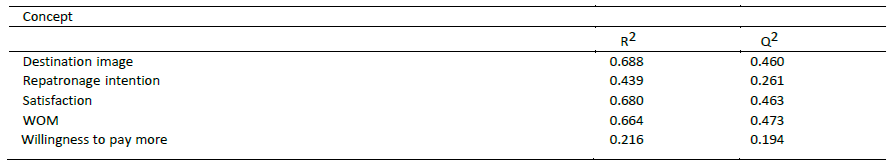

As shown in Table 5, R2 was calculated to assess the model’s explanatory power (Hair et al., 2014), revealing that all dependent constructs were above 0.10 (Falk & Miller, 1992). Additionally, positive Stone-Geisser’s Q2 values were estimated using blindfolding (Henseler et al., 2009), indicating good predictive power as the values were above zero.

As a result of reliability and validity analysis, and measurement of the model have been established. The hypotheses formulated in the research model can now be examined, and it is proposed that the model aligns well.

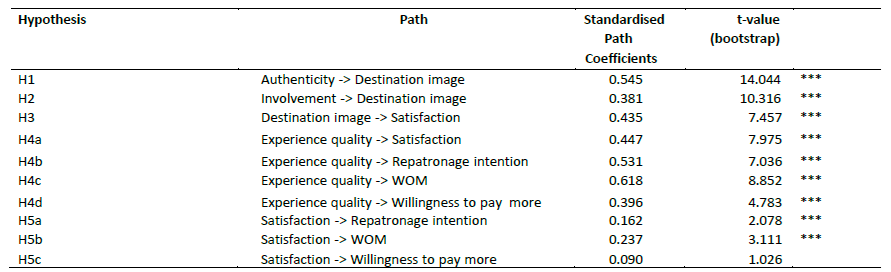

Results of the structural model

Boostrapping was completed with individual sign changes of 5,000 samples to determine parameter significance. As seen in Table 6, the results show that authenticity has a significant and positive influence on destination image (H1; β = 0.54; p < .01). Likewise, involvement has a significant and positive influence on destination image (H2; β = 0.38; p < .01). Besides, destination image has a significant and positive influence on satisfaction (H3; β = 0.43; p <.01) and similarly experience quality has a significant and positive influence on destination image (H4a; β = 0.45; p < .01). Experience quality has a significant and positive influence on re-patronage intentions (H4b; β = 0.53; p < .01), WOM (H4c; β = 0.62; p < .01) and willingness to pay more (H4d; β= 0.4; p < .01). Satisfaction has a significant and positive influence on re-patronage intentions (H5a; β = 0.16; p < .01) and WOM (H4a; β = 0.24; p < .01). However, it has been demonstrated that satisfaction has no significant effect on willingness to pay more (H5c; β = 0.09).

Based on R2 values of the structural model, the highest rate of destination image was 69%, and the lowest rate of willingness to pay more was 22%. These findings demonstrate that the disclosure rate of the study variables had a high and medium level of disclosure (Henseler et al., 2014).

Discussion

Nowadays, cultural tourists have many options for cultural and entertainment offerings, leading to intense competition in the cultural market. The main purposes of cultural tourists are to get information and gain experiences concerning traditional and local properties. In this context, the experience of tourists is a substantial component of cultural heritage tourism. For this reason, understanding the behavioural patterns of tourists engaged in cultural heritage tourism is crucial for the survival of areas with cultural heritage sites, helping them withstand the passage of time and elucidating the processes that lead tourists to recommend them. Therefore, enhancing the understanding of tourist behaviour is essential for cultural heritage and tourism professionals, planners, marketing managers, and officials. Research on satisfaction with visiting historical, cultural areas in the context of heritage tourism is important to develop correct tourism strategies.

The research findings indicate that the quality of experience provided to tourists visiting cultural heritage places positively influences satisfaction, intention to recommend, willingness to pay more, and word-of-mouth. These findings corroborate previous studies that have identified positive relationships between satisfaction with experience quality, willingness to pay, word-of-mouth, and intention to recommend (Aliedan et al., 2021). Additionally, positive relationships were found between involvement, authenticity, and destination image, consistent with previous research by Lu, Chi, and Lui (2015) and Prayag and Ryan (2012). The positive and significant relationship between destination image and tourist satisfaction has been well-documented in the literature (Aliedan et al., 2021; Uslu & Inanır, 2020). Destination image plays a crucial role in tourists’ decision-making processes, directly influencing their behavioural intentions. Corroborating with this, Lee & Xue (2020) argue that destination image directly affects tourist satisfaction. Uslu et al. (2020) also discuss the relationship between the dimensions of destination image, destination curiosity and loyalty. Research findings indicate significant relationships between the dimensions of the destination image, curiosity and loyalty.

This research advances knowledge by proposing hypotheses to demonstrate the effects of authenticity and involvement on destination image and examining the impact of experience quality on behavioural intentions compared to the relationship between satisfaction and behavioural intentions. Consequently, this study contributes to the literature on destination image, experience quality, and behavioural intentions for several reasons. Firstly, it extends destination image literature by empirically analysing the effects of authenticity and involvement on destination image across tangible and intangible attributes. Furthermore, it sheds light on Ancient Side tourists’ evolving perceptions towards a positive and sustainable destination image (Gezici, 2006; Uslu & Inanır, 2020; Uslu et al., 2020). Secondly, the comparison between the effects of experience quality and satisfaction on behavioural intentions provides valuable academic and managerial insights to enhance loyalty attitudes among tourism professionals. Thirdly, the study highlights a lack of significant effect between satisfaction and willingness to pay more, prompting further exploration of this linkage in different contexts. Finally, this research contributes to tourism management literature and consumer research, as the proposed model can be applied in various contexts.

Conclusions and implications

Conclusions

In this research on the effect of originality and involvement on destination image, the findings demonstrate that satisfaction is influenced by destination image. Moreover, destination image is also shaped by authenticity and involvement. The findings also demonstrate that developing re-patronage intentions, WOM recommendations, and willingness to pay more can be facilitated through experience quality and satisfaction. Notably, the study highlights that satisfaction does not significantly impact willingness to pay. The findings underscore the pivotal roles of satisfaction and experience quality in shaping tourist re-patronage intentions and WOM motivation. However, for achieving a higher willingness to pay, the quality of experience emerges as the most critical factor, while satisfaction plays a minor role.

Theoretical contributions

This study makes a significant contribution to the literature by examining tourist behaviour in heritage destinations. The analysis reveals that destination image comprises five dimensions: infrastructure and socio-economic environment, natural and cultural resources, pleasant atmosphere, social setting environment, and overall image, while experience quality can be characterised by three dimensions: learning, enjoyment, and escape. These dimensions are substantial for understanding the determiner of tourist behaviour and perceptions in heritage destinations. These dimensions are also important to explore the effects of tourists’ involvement levels on shaping a positive destination image. Unlike previous research (Lu et al., 2015, Prayag & Ryan, 2012), a fundamental contribution made by this study is its singularity in segmenting determiners of tourist behaviour in heritage destinations. This study also provides empirical evidence for understanding destination image, aiming to comprehend visitor satisfaction, experience quality, re-patronage intentions, willingness to pay more, and word-of-mouth and their interrelationships within a heritage destination. Even though the image of heritage sites has been examined in previous research, this study contributes to the literature by defining it across tangible and intangible attributes. Finally, this research contributes to tourism management literature and consumer research, as the proposed model can be applied in various contexts.

Practical implications

Based on this research, there are some managerial implications. These results suggest that both public and private organisations overseeing tourist destinations should design visitor experiences that consider authenticity and involvement to enhance destination image and elevate customer satisfaction. This approach encourages repeat visits and promotes positive recommendations to others. Similarly, designing visits to heritage destinations with a focus on experience quality can yield similar outcomes. Furthermore, to increase willingness to pay, it is imperative to offer a high-quality cultural tourism experience, wherein tourists gain knowledge about the heritage destination and enjoy the experience while deeply engaging with the surroundings.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

To enhance the robustness of the findings, researchers are encouraged to consider the limitations of this study. Specifically, the proposed model could be further enriched by exploring additional relationships or incorporating new variables. Additionally, conducting a multi-group analysis that considers first-time visitors and repeat visitors could offer valuable insights into familiarity with the touristic destination. Moreover, future studies could explore satisfaction based on perceptions and incorporating expectations. Comparing results across samples from different countries’ heritage tourism destinations through multi-group analysis would also be beneficial. Therefore, scholars are urged to replicate this study in diverse contexts while considering all the limitations outlined in the present research.