Clinical case

A previously healthy 32-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency room with lower abdominal pain. The pain began 3 days before and was aggravated by abdominal wall muscles contraction. Dysuria was also mentioned. There was no fever.

She was taking oral contraceptives, but she had a history of IUD (intra-uterine device) and IUS (intra-uterine system) rejection.

At physical examination, a tender mass in the hypogastric region/left iliac fossa was palpable.

Laboratory findings only revealed elevated PCR (42,8 mg/L). There was no leucocytosis and urine analysis was unremarkable.

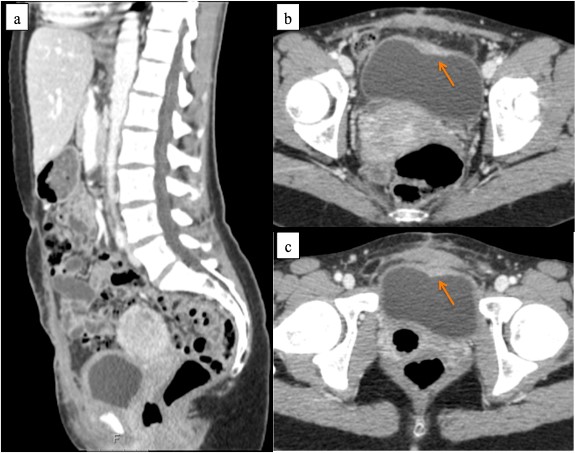

An ultrasound and CT were performed in the emergency room (Figure 1).

Figure 1: a - ultrasound image with Power-doppler showing heterogeneous hypoechoic, ill-defined and serpiginous tract, extending from the anterosuperior bladder (blue star) wall to the rectus abdominis muscle (orange dashed lines); b - corresponding axial CT image with heterogeneous enhancing mass-like extending from the bladder to the rectus abdominis muscle (orange dashed lines).

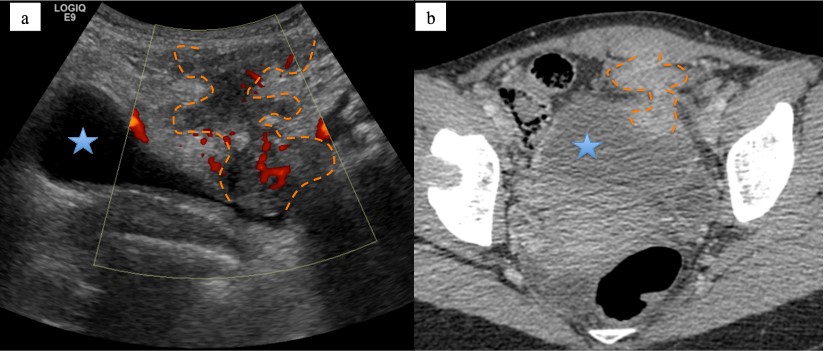

The patient underwent MRI in the following week (Figure 2).

Figure 2: pelvic MRI showing ill-defined mass (red dashed line) in the extraperitoneal cavity measuring 7x5x4 cm, invading the left rectus abdominis muscle and focally the dome of the bladder, with intermediate T2 signal (a) and high T2FS signal compatible with oedema (b), there is also extensive oedematous infiltration of the surrounding fatty tissue from the space of Retzius to the presacral space. The mass shows restricted diffusion (green arrows) - low ADC value (c) and high signal in b1000 (d) - due to either abscess or tumor infiltration. In the post-gadolinium sagittal image (e) the enhancement of the lesion walls and the absent enhancement of the central part is visible. The ovaries (yellow stars) have normal appearance and size, showing multiple physiologic follicles (a).

Inflammatory parameters were increased (RCP - 247 mg/L and leucocytosis - 17x109/L with neutrophilia 80%).

Aspiration cytology revealed gram-positive bacteria (Parvimonas micra) and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

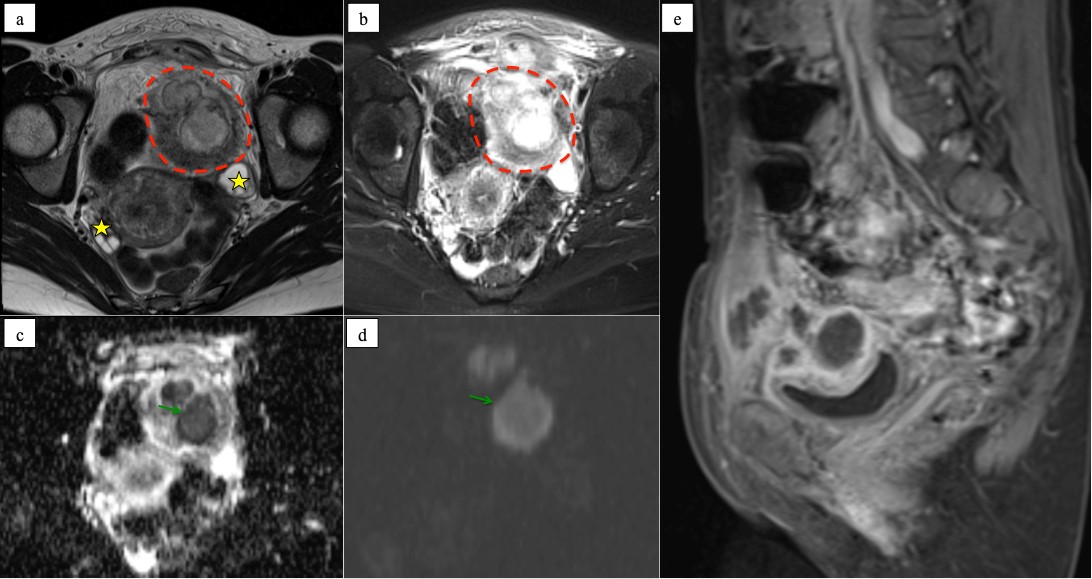

The patient underwent surgical resection and the histopathology findings were granulation tissue and an inflammatory process with abscess in the cellular subcutaneous tissue and trans-mural extension in the bladder, showing microorganisms compatible with Actinomyces (Figure 3).

Figure 3 (a-b): (a) A large colony of Actinomyces (dark arrowhead) within an abscess, enveloped by an abundant inflammatory infiltrate. Haematoxylin-eosin, 400x. (b) Actinomyces colonies can present with a darkly staining eosinophilic rim (dark arrowheads) at the periphery of the colony referred to as the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon, which mainly consists of immunoglobulin and cell debris and can occur around colonies of fungi, bacteria and other parasitic organisms. The colony is surrounded by a dense inflammatory infiltrate, in which neutrophils (white arrowheads) are the main component. Haematoxylin-eosin, 600x.

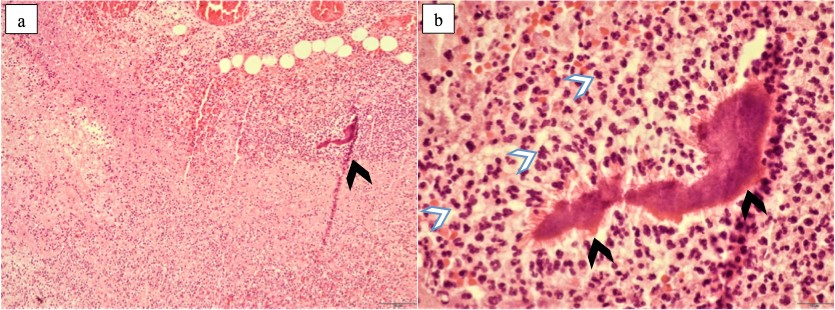

She was discharged with antibiotherapy (doxycycline 100mg q.i.d. during 10 days, then switched to amoxicillin 1g t.i.d. due to gastrointestinal side effects). Follow-up CT scan showed no relevant abnormalities (Figure 4).

Discussion

Actinomycosis is a rare chronic infection, caused by gram-positive bacteria from the Actinomyces species. Actinomyces is part of the endogenous flora of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and female genital tract. As a result, the frequency of involvement is 50-65% in the cervicofacial area, 15-30% thoracic and 20% abdominopelvic. 1

In order to cause infection, disruption of the mucosal barrier is imperative, which can be caused by trauma, surgery or foreign bodies. 2

Long-standing IUD is a risk factor extensively mentioned in the literature 3, however, in our case the patient had one IUD for 6 months and one IUS for 1 month, both rejected. We have not found correlation between actinomycosis and IUD rejection in the literature. We hypothesize that microtrauma occurring during the rejection process is a predisposing factor for infection.

Disease may occur months or years after the removal of an IUD. 1

Pelvic actinomycosis is a difficult radiologic diagnosis, often indistinguishable from malignancy. In our case, the differential diagnosis was malignancy of the urachus, due to its topography.

The disease can spread extensively to the uterus, urinary bladder, rectal area, urachus, abdominal wall and peritoneum. It is also characterised by transfascial spread and sinus tracts.1

Rim-enhancing abscesses within the mass and extensive inflammatory extensions are usually present. Due to the characteristic presence of fibrosis, solid parts of the mass and the surrounding soft-tissue strands tend to show strong contrast enhancement.4

Regional lymphadenopathy and ascites are usually absent, which helps in the distinction from malignancy.5

Most actinomycotic infections are polymicrobial in nature6, which justifies the identification of Parvimonas micra in the cytology of our patient.

Microorganism diagnosis may be obtained by microscopic examination and the presence of sulphur granules stained with a 1% methylene blue solution.3

Histopathology shows suppurative and granulomatous inflammatory changes, connective proliferation and sulphur granules, which have also been found in infections caused by Nocardia brasiliensis, Streptomyces madurae and Staphylococcus aureus. These granules are yellowish particles and are formed by clumps of filamentous Actinomyces surrounded by neutrophils.3

The usual treatment for actinomycosis consists of high and prolonged doses of antibiotherapy (penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline or clindamycin).6 However, in some cases it is necessary to proceed to surgical drainage. In those patients, the duration of antibiotherapy may be reduced (3 months).2