Case Presentation

A 36-year-old female patient seeks medical attention from her primary care physician for a 2-year history of right back pain associated with diminished strength in her left arm. She has a past medical history of asthma and recurrent respiratory infections in childhood and of an event of thoracic trauma 14 years before. Physical examination is unremarkable. No history of cancer in the family is reported.

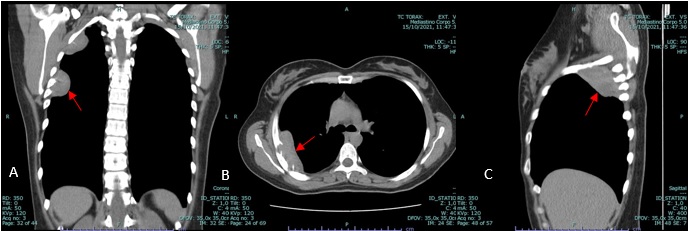

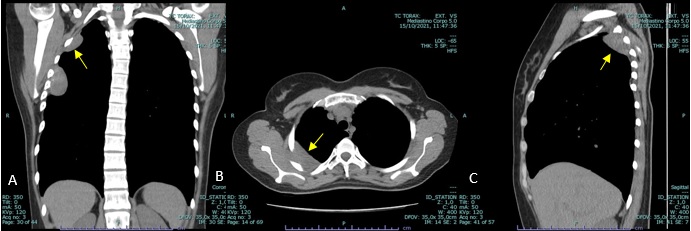

The patient is referred to our hospital to a Pulmonology consultation following the findings of a non-contrast enhanced thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan which shows a nodular, oval-shaped, solid and homogenous mass with low attenuation and soft tissue density located in the upper third of the right thoracic wall and in intimate relation with the intercostal muscles. This mass measures approximately 7.5 x 4 x 2.7 cm and it seems to protrude and erase the adjacent inner border of the 4th and 5th costal arches. Its regular borders are well defined from the adjacent pulmonary parenchyma and from the serratus anterior muscle (see figure 1). Above this lesion, in close proximity with the right pulmonary apex and located in the thoracic inlet, we find another nodular mass with the same tomographic characteristics measuring 4.6 x 3.6 x 2.4 cm, indenting the inner border of the 2nd costal arch (see figure 2). The two lesions are not in communication with each other, seeming to be two different processes with the same etiology.

Figure 1: Coronal (A), axial (B) and sagittal (C) soft tissue window, non-contrast enhanced CT showing soft tissue mass (red arrow).

Figure 2: Coronal (A), axial (B) and sagittal (C) soft tissue window, non-contrast enhanced CT showing the second soft tissue mass (yellow arrow).

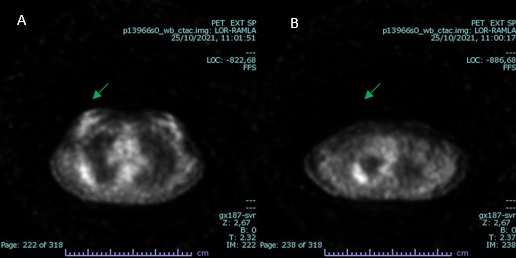

Afterwards, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan is performed, which shows increased 18F-FDG uptake in both lesions, with an SUV of 2.7-2.9 (see figure 3).

Figure 3: PET scan images demonstrating increased 18F-FDG uptake in both lesions (green arrow); SUV 2,9 (A) and 2,7 (B).

These findings are followed by a CT-guided biopsy of one of the thoracic wall lesions and the histopathological report suggests a low grade fusocellular proliferation without necrosis or pleomorphic morphology and with immunohistochemical and histomorphologic characteristics hinting a solitary fibrous tumour, but with overall weak positivity for CD34.

The case is later discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting, and surgical resection of both lesions and new histopathological study on the removed pieces is decided for a definite diagnosis.

Resection of the tumoral masses is performed and two pieces with 20g and 19g of soft, pinkish, irregular tissue are extracted. Final pathology results are consistent with multicentric, low grade fusocellular neoplasia with positive margins measuring 6 × 4.5 × 2.5 cm and 5.5 x 4.5 x 2 cm in size. Differential diagnosis included multifocal extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis; solitary fibrous tumour; disseminated leiomyomatosis - like proliferation and benign metastasizing leiomyoma. The multifocal nature and the immunohistochemical panel obtained, combined with the location of both lesions, favoured fibromatosis.

Later genetic testing by Sanger sequencing detects the mutation S45F in the CTNNB1 gene, confirming the diagnosis of multifocal extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis.

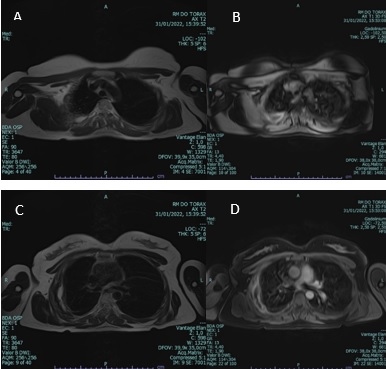

Postoperative magnetic resonance study (MR) at 1-moth follow-up shows no signs of disease (see figure 4).

Discussion

Desmoid-type fibromatosis is a relatively rare mesenchymal neoplasm which arises from a proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Although it exhibits benign morphology it is classified as an intermediate malignant neoplasm due to both its locally aggressive and infiltrative behaviour on adjacent structures and its high rate of local recurrence, despite its non-metastasizing progression.1,2Its etiology remains yet to be well documented, but it is believed that trauma, previous surgery interventions and mutations in the CTNNB1 gene are all implicated factors in the development of such condition. It may originate in any part of the body with extremities, chest wall, back, and thigh being the most common sites.3 According to the anatomical site, desmoid-type fibromatosis can be divided into extra-abdominal fibromatosis (60%), fibromatosis of the abdominal wall (25%) and intra-abdominal fibromatosis (8-15%).4 Of these tumours, multicentric extra-abdominal desmoids are rather rare.5 Estimated incidence is 5-6 cases per 1,000,000 population and is more prevalent in 30-40 year-old patients, with a 2:1 female-male ratio.6 In this case we present a young female patient with chronic back pain and history of thoracic trauma. Initial imagiological and histopathological work-up was inconclusive, but it pointed towards two locally aggressive, low grade non-metastasizing soft tissue masses with mesenchymal origin located in the thoracic wall. Differential diagnosis included multicentric extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis, solitary fibrous tumour, disseminated leiomyomatosis - like proliferation and benign metastasizing leiomyoma. Macroscopic evaluation of post-surgical resection lesions showed pinkish, soft, rubbery firm masses, with irregular margins. The cut section revealed a whitish surface with fascicular appearance and congestive areas. Microscopically, results were consistent with multicentric, low grade fusocellular neoplasia with proliferation of spindle-shaped cells with elongated nuclei set in collagenized background stroma, typical morphological features of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells were focally positive for 𝛼-smooth muscle actin and calponin. Nuclear immunoreactivity for 𝛽-catenin was observed. No immunostaining was obtained with antibodies against AE1/A3, Ber-Ep4, calretinin, S100 protein, HALK, CD34, CD99, C-Kit, STAT6, CD34, CAM 5.2 and oestrogen receptors. Ki 67 staining was lower than 5%. Genetic testing by Sanger sequencing detected the mutation S45F in the CTNNB1 gene, confirming the diagnosis of multifocal extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis.

Desmoids usually stain positively for nuclear beta-catenin, vimentin, cyclo-oxygenase-2, tyrosine kinase, and negatively for desmin, S-100, CD34, and c-KIT.7

Desmoid fibromatosis can be subdivided into two groups, with approximately 90% being sporadic and the remaining 10% being hereditary (related with Gardner syndrome, a form of FAP, where a dysregulation of the APC tumour suppressor gene is verified). The most common mutation in sporadic cases involves an activating mutation in CTNNB1, the gene encoding β-catenin. The two most commonly identified mutations are the T41A and S45F in 50% and 25% of cases, respectively.8 In both groups, these changes imply abnormal regulation of the WNT signalling pathway, which results in accumulation of β-catenin in affected cells, leading to cell proliferation and differentiation.9 According to some studies, the S45F mutation is related with a higher risk of recurrences after surgery, as well as the increased possibility of progressive disease.10

Treatment for desmoid tumours has traditionally been surgical resection as well as radiation. More recently, an active surveillance approach has been proposed as the strategy of choice.9 Other nonsurgical management includes hormone therapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication.

Postoperative follow-up was conducted with magnetic resonance study (MRI), as we have reasons to believe it is the study of choice for diagnosing, assessing and monitoring extra-abdominal desmoid tumours,11 showing no signs of disease.

As desmoid tumours pose to be a diagnostic challenge being rare entities with non-specific imagiological findings, we relied on the identification of clinical and genomic biomarkers to facilitate successful patient management.