1. Introduction

Digitalization has led to a crisis in traditional news media and to an upheaval in media ownership (Nielsen, 2017; Schiffrin, 2018). A primary research concern has been that the motives driving media owners will shift from financial and public service to overtly political and ideological (Nielsen, 2017). The term “media capture” has been suggested as a way to describe how various interests may take control of news media outlets (Schiffrin, 2018; Stiglitz, 2017). In Nielsen’s (2017) view, the threats to media ownership arise because of the upheaval of the traditional advertisement-based business model that news media across most of the world relied on prior to the rise of digitalization in the 2000s. According to Nielsen (2017), as the profits of news media drop, the traditional economic motives for owning a media business also drop, leaving other incentives for media ownership to take center stage, primarily political or otherwise ideological motives.

Examples of problematic changes in media ownership can be found in many countries. Thus, journalists working for the Baltimore Sun, an American newspaper taken over by a conservative broadcast mogul, David D. Smith, recently protested about the content and wording of stories in their own newspaper about immigrants and members of the LGBT+ community (Shen, 2024). In France, reporters have turned to strike in response to a paper being taken over by a billionaire and the appointment of right-wing editors (Dodman, 2023), fears that have also led to strikes among Italian journalists (Agence France Presse, 2024). In Denmark, changes in ownership have also stirred up public debate. For instance, when a local digital newspaper recently ran a favorable story about a mayoral candidate, the first version of the article did not mention that that candidate also owned 100% of the newspaper, nor that the author of the article was the candidate’s brother (Sørensen, 2024). Also, recently, a former spin doctor for a Danish right-wing political party bought the online news site Kontrast, a right-leaning alternative news site that had been struggling financially (Lange, 2023). The buyer also owns a communication bureau that specializes in public affairs. In a similar vein, three new stock owners of the political news site Frihedsbrevet were revealed to be business people with their main business interests in either car sales or realty development (Mathiessen, 2023; Olsen, 2023). These latter types of media owners, owners who are primarily active in other industrial fields than news media, have previously been described as “entrepreneurs” and are a well-established type of media owner in many countries, though they are usually associated with less established media markets (Stetka, 2012; Tunstall & Palmer, 1991). According to Humprecht (2019), these kinds of owners often founded or inherited their companies, though they are also the type to open new online start-ups. Regardless of media type, media entrepreneurs often act as managers of their media outlets or exercise control by monitoring the managers they have hired (Humprecht, 2019). At the same time, they are the kind of owners that research suggests are on the rise due to digitalization, even in established democracies and media systems (Nielsen, 2017), where they so far have been less prevalent, like in the democratic corporatist media system.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: first, we will turn our attention to studies of media ownership, ownership transparency, and media capture with a focus on studies from European Union member States. Then, we will situate the study of ownership within the broader perspective of media systems theory. Finally, we will turn to our methodology, which originates from the European Union-funded research project Euromedia Ownership Monitor. Our results show that while much is the same regarding ownership and ownership transparency in Denmark, the rise of digitalization and new digital news media at the same time present a challenge and raise a red flag regarding which kinds of ownership are emerging in Denmark. Indeed, some of the new owners of new digital news media fall into the category of “media entrepreneurs”, which potentially raises the risk of media capture by ownership. However, without any rules regarding transparency of their other financial or political activities, this development has left a small but open door for a kind of media ownership often associated with negative democratic consequences (Nielsen, 2017; Schiffrin, 2018; Stetka, 2012).

2. Media Ownership

In general, the study of news media ownership has been a focus of news media research due to the very simple assumption that ownerships matter (Schnyder et al., 2024; Sjøvaag & Ohlsson, 2024; Smith et al., 2021; Willig & Blach-Ørsten, 2022). Indeed, the question of ownership is linked to assumptions that ownership can influence journalistic autonomy, news content, and the overall question of democracy, media pluralism, and diversity (Sjøvaag & Ohlsson, 2024). Back in 1992, the European Commission published a green paper on pluralism, media ownership, and media concentration based largely on concerns raised in the European Parliament (Hitchens, 1994). Based on, among other things, the then-current development of Berlusconi’s expanding media ownership in Italy, the European Parliament wanted to find a way to ensure journalistic ethics, professional journalistic standards, and overall freedom of expression (Hitchens, 1994) by looking at ways to control media ownership and media ownership concentration. Therefore, the study of ownership concentration has been one of the central pillars of media ownership studies, with results from many previous studies showing that media ownership in many countries is indeed highly concentrated (Doyle, 2015; Noam, 2016). Looking back at the green paper 30 years later, Meier and Trappel (2022) conclude that not much has happened regarding this issue and that, indeed, ownership concentration is still soaring while regulation is still limited. In other words, while concerns about ownership have risen due to digitalization (Nielsen, 2017; Schiffrin, 2018), regulation of ownership has not kept pace, according to Meier and Trappel (2022).

According to Sjøvaag and Ohlsson (2024), the study of media ownership is very diverse, and it touches on a range of issues such as monopolization, how commercial, political, and ideological motives drive media ownership, the indirect power of owners on news content and democracy as well as different types of ownership. Research distinguishes between various types of ownership (Benson, 2018; Sjøvaag & Ohlsson, 2024). One way of distinguishing between ownership forms is the simple, overall categorization into three types. One version of this is a differentiation between private, public, and private State-owned media (Hanitzsch & Berganza, 2012). A slightly different way is presented by Benson (2018), who uses the categories “public media”, “stock market traded”, and “privately held” commercial media, and “civil society”/“nonprofit media”. Despite the sometimes different categories, looking at the question on a more general level, there seems to be more than some agreement on the different kinds of ownership. Thus, there is a common distinction between public ownership (often understood in terms of State ownership of public service news media) and private ownership, often understood as stock ownership but also ownership by either trust or foundation (Benson, 2017; Benson et al., 2018; Sjøvaag & Ohlsson, 2024). Studies of public service media are often linked to questions of quality and democracy, with results showing that public service news media have more in-depth news and critical news than commercial media (Benson, 2018). Studies also link public service to a more knowledgeable public (Iyengar et al., 2010) and better-functioning democracies compared to media systems without public service (Humprecht & Esser, 2018; Neff & Pickard, 2021). However, some public service media have an economic model that mixes license fees, taxes, and advertising revenues, making them also vulnerable to financial pressures (Humprecht, 2019). Moreover, in many countries, public service media is under political pressure, often being criticized for serving a too selective, elite audience or for competing with private news media (Arriaza Ibarra & Nord, 2014; Humprecht & Esser, 2018).

The study of private ownership has been linked to a focus on media moguls like Hearst (the United States), Murdoch (Australia and Great Britain) or Berlusconi (Italy; Stetka, 2012; Tunstall & Palmer, 1991) and more recently to the rise of the so-called “media entrepreneurs”. Indeed, parts of the literature single out how media owners with primary financial interests outside the news media are on the rise (Stetka, 2012; Tunstall & Palmer, 1991). Humphreys (1996) originally argued that these types of owners were found in less established media markets and pointed (again) to Italy as an example. However, in his study of media markets in Eastern and Central Europe, Stetka (2012) shows how this type of ownership, which he terms “ownership by business tycoons”, is on the rise. He also argues that the increased entanglement of media, politics, and, typically, national business interests that these types of media owners embody are similar to some of the ownership challenges found in Italy and Greece and raise concerns about whether news media owned by businesses tycoons are being instrumentalized, or captured, to serve instead business/political interests rather than public/journalistic interest (see also Schnyder et al., 2024).

3. Transparency

Turning to the question of ownership transparency, this is often highlighted as a way to increase democratic control of the news media, as well as a way to secure media pluralism and trust in journalism (Figueira & Costa e Silva, 2023; Meier & Trappel, 2022). Overall, transparency has become recognized as a democratic ideal in many countries around the world since the 1960s and 1970s (Schudson, 2020) and is commonly linked to ideals of how democracies best function and how to keep out undue influences and corruption in political decision-making (Meier & Trappel, 2022; Schudson, 2020). More recently, transparency has been introduced as a journalistic ideal for newsrooms to open up the process of news-making and the decisions taken by journalists and editors every day that influence which stories make the news and which do not (Blach-Ørsten & Lund, 2015; Masullo et al., 2022). Similarly, transparency has become a political focus with regard to ownership of companies, including media companies (Antoniou et al., 2021; Fernando & Berkhout, 2022). Especially the study of the transparency of beneficial owners has been in focus: “identifying who ultimately owns or controls companies and other types of corporate structures (the beneficial owner) is a key financial integrity measure that also has important governance and transparency objectives and is relevant for macroeconomic and financial stability” (Fernando & Berkhout, 2022, p. ix).

Using data from the Media Pluralism Monitor, Smith et al. (2021) investigated the level of ownership transparency in more than 30 European countries. They highlight that ideally, there should be transparency of both beneficial and direct ownership, as well as information about owners’ financial or other relations that could influence editorial decisions. However, they conclude that overall, there are no specific rules of media transparency in many European countries and, thus, not the required level of transparency. In a study of news media ownership based on data from Media for Democracy Monitor, Meier and Trappel (2022) reach a similar conclusion regarding the practice of media ownership transparency. They do, however, also find and highlight some best practice examples where the necessary transparency information is made easily accessible. These countries include, for instance, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and South Korea. The authors, however, also state that transparency, in itself, is no guarantee for either media pluralism or a “better” democracy.

4. Media Capture

With the spread of digitalization across media markets, researchers have remarked on both the possible dangers and benefits of this technology. On the bright side, digitalization has made news available to a far greater amount of people than ever before (Nielsen, 2017), while on the not-so-bright side, digitalization has disrupted news media’s traditional advertisement-base model leading to lay-offs, closures, merges and the rise of more political and ideological based online news sites (Blach-Ørsten & Mayerhöffer, 2021; Nielsen, 2017; Schiffrin, 2018). This again has led to a research focus on the concept of “media capture”. While the concept of “transparency” was plucked from the vocabulary of political science (Schudson, 2020), the concept of “media capture” has been taken from the study of economics (Nielsen, 2017; Schiffrin, 2018; Stiglitz, 2017). In economics, the term refers to “a situation in which regulators become overly empathic with or supportive of the agencies they are meant to be regulating” (Schiffrin, 2018, p. 1034). In media studies, capture has been linked to studies of ownership as well as studies on technologies and platforms (Schiffrin, 2018, 2021). In relation to the question of ownership, the concept of “media capture” refers to news media being controlled by private interests that are not focused on profit or serving the public interest but rather on using news media as a tool for advancing political ambitions or navigating the grey zone between business and politics (Besley & Prat, 2006; Gross & Jakubowicz, 2012; Nielsen, 2017). Media capture by ownership is not a threat unique to private news media but can also be a threat to public service news media, as witnessed by recent events in both Hungary and Poland (Dragomir & Aslama Horowitz, 2021; Schiffrin, 2018). Indeed, based on the writings of scholars above, it is possible to sketch a taxonomy of media capture regarding both private and public service news media.

Private media:

Media capture of private media by a wealthy individual or a corporation: this can result in owners, whose primary financial interests lie outside the news media, using the news media outlets they own to advance and protect these interests.

Media capture by a wealthy individual or a corporation for political or ideological reasons: this can lead to owners using news media outlets as ideological platforms to serve specific political interests and audiences while ignoring or criticizing opposing views.

A mixture of the above.

Public service news media:

Media capture by the Government: this can lead to the Government taking control of the news media by, for instance, exerting political pressure on regulatory bodies, applying financial constraints on public service new media, or laying off journalists they do not agree with and replacing them with more “friendly” staff (Wiseman, 2021).

Media capture by the Government can also be combined with media capture by wealthy individuals who are either close to the Government or share its ideology.

In summary, the study of news media ownership has focused on the concentration of ownership based on the assumption that ownership matters regarding media pluralism, media content, and journalism’s role in democracy. Digitalization has emphasized the importance of studying media ownership as new threats have emerged, while at the same time, regulation and transparency have not done much to damper the challenges. Indeed, studies show that new types of ownership are emerging, like ownership by the so-called “media entrepreneurs”, owners whose main business interests lay outside the news media or whose interests may be far more political and ideologically based. At the same time, studies also show how some Governments have captured public service news media to serve their political goals. Both developments raise questions about media capture by ownership and thus accentuate the need for ownership transparency, especially regarding beneficial owners and owners’ affiliation with politics. Indeed, the question of ownership has become so significant that media ownership should now be regarded as a crucial dimension of media systems (Neimanns, 2021), which is the focus of the next section.

5. Ownership in Different Media Systems

The changes and challenges of ownership in the digital age play out differently in each country but still have similarities at the aggregated level of media systems. Thus, recent research into media systems is increasingly addressing both digitalization and ownership as important dimensions influencing the clustering of countries into different media systems (Humprecht et al., 2022; Neimanns, 2021). Originally, media systems in the Hallin and Mancini (2004) version described three media systems in the Western world: the democratic corporatist model, characterized by a strong newspaper industry as well as a strong role of the State evidenced by media subsidies and public service news media, includes Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, Netherlands and Austria. The polarized pluralist model, marked by weak professionalism and a high degree of political parallelism, includes France, Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Spain. Finally, the liberal model, which is defined by market-dominated journalism and a neutral commercial press, encompasses the United States, Britain, Ireland, and Canada.

Hallin and Mancinis’ (2004) models pre-date the digital era, and thus, researchers have sought to update the three models in accordance with the many changes since 2004 (Brüggemann et al., 2014; Humprecht et al., 2022). Humprecht et al. (2022) state that they seek to rethink the model in response to the rise of social media, the digitalization of traditional news media, the increased fragmentation of media audiences, and the rise of politically biased news media. They also add a focus on media freedom, which was missing from the original model, and which includes a focus on the political influence on the news media, as well as the structure of media ownership. Concerns about ownership have previously been mostly associated with the polarized pluralist model, with Italy and Greece being among the often-mentioned countries, and occasionally with the liberal model, most often exemplified by the growing fragmentation and polarization of the United States media market.

These new research concerns, as well as the updating of the dimensions that constitute media systems and the addition of countries, results in a new configuration of three media systems for the digital age (Humprecht et al., 2022). The liberal model is replaced by a hybrid model that is characterized by low State support, low journalistic professionalism, and a fragmented media market. This model includes the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia and Lithuania. The polarized pluralist model is characterized by low levels of State support, low levels of journalistic professionalism, and a high level of political parallelism. This model includes Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. Finally, the democratic-corporatist model, (still) characterized by a high degree of journalistic professionalism, an inclusive market, State support, and a low level of political parallelism, includes Finland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Austria, Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands.

In summary, while digitalization has caused changes in countries individually, it has also shaped the basis of a reconfiguration of a model of media systems. In this reconfiguration, new dimensions of media systems have been added, such as a focus on media freedom and ownership structures, and new countries from Central and Eastern Europe have been added as well. However, on a systemic level, one media system stands out, the democratic-corporatist system, as a system with less significant change than the other media systems and a system described as more “stable” than the other media systems (Humprecht et al., 2022). This conclusion concerns the aggregated level but begs the question of just how digitalization is shaping the individual countries within this more stable system. So, while many studies of ownership and media capture focus on countries where the challenges are already in clear evidence, how do these challenges look from a “best” case perspective? We will investigate this with Denmark as the focus of our case study.

6. Denmark as Part of the Democratic Corporatist Media System

The Danish media system has been and still is characterized by strong both public and private news media, media subsidies for private media, a high degree of journalistic professionalism as well as a high degree of press freedom (Blach-Ørsten et al. 2021; Esmark & Blach-Ørsten, 2008; Olesen, 2020). Media users have high trust in legacy news media and favor public service both on and offline and the online homepages of traditional newspapers (Schrøder et al., 2023). Regarding media freedom, Denmark ranks at the top of the yearly media freedom index reports published by Reporters Without Borders (https://rsf.org/en/index). Traditionally, the Danish media system has been known as a dual media system, where public service broadcasters and private print/online and broadcast media co-exist (Kammer, 2017). Regarding structure, the system is characterized by State-owned public service media dominating the audiovisual media market. At the same time, the print/online media market is also dominated by a few large, private owners (Willig & Blach-Ørsten, 2017), with private ownership being divided into either ownership by stock or by private foundation (Kammer, 2017). Yearly reports from the Media Pluralism Monitor highlight that in Denmark, there are no separate rules nor specific requirements regarding ownership for media companies, and the Media Responsibility Act’s main aim is not to regulate ownership or control (Rasmussen et al., 2022; Simonsen, 2023; Willig & Blach-Ørsten, 2017). Due to the absence of a media-specific competition law, Denmark scores a medium risk assessment regarding threats to market plurality as well as ownership transparency (Simonsen, 2023). However, based on the few cases that have been the subject of regulation by the competition authorities in recent years, the law fulfills its purpose (Willig et al., 2022).

The description of media ownership in Denmark is largely the same in each of the yearly Danish country reports from the Media Pluralism Monitor. However, changes in ownership have taken place, especially with the onset of digitalization of the Danish media market from the 2000s and onwards (see also Kammer, 2017). First, in 2014, Danish media policies changed to include so-called “innovation subsidies” with the intent to support new kinds of news media, whether online or in print (Kammer, 2017). This means that the Danish media market today consists of an increasing number of (mostly) digital news media, where owners are neither the State nor legacy news media, but instead different kinds of private owners. Some of these new digital media have received innovation support from the State, and some have not. Roughly, these “new” news media, sometimes also named “digitally-native news media”, fall into two overall categories (Blach-Ørsten & Mayerhöffer, 2021). First, there are the innovative, alternative news media, where the focus is on being journalistically innovative and developing new formats and new ways of doing journalism for, typically, a select audience. Second, there are hyperpartisan alternative news media, where the focus is on being a “political corrective” to a perceived biased mainstream media system. These hyperpartisan news media can be found on both the left and right of the political spectrum, though most often on the right (Blach-Ørsten & Mayerhöffer, 2021; Brems, 2023).

Another feature that stands out in the Danish media system regarding ownership is the tradition of foundations’ ownership of news media, especially newspapers. According to Thomsen et al. (2018), ownership by industrial foundations can be found around the world in companies like Bosch (Germany), Hershey (United States), and Rolex (Switzerland). In short, an industrial foundation is a tax-exempt or charitable foundation that owns or controls one or more conventional business firms. This type of ownership is common in Northern Europe and particularly in Denmark. The difference between foundations in Northern Europe and, for instance, in the United States is that a foundation in Northern Europe has a company purpose - the preservation and development of the business. These characteristics of foundation ownership are formalized in the foundation charter, which makes ownership of the company the most important objective for the foundations in question. Second, the foundation ownership is not subject to the travails of succession to new generations of the founding family. Ownership remains with the foundation; it is not an option for new generations to cash in by selling their shares. Thirdly, foundations are patient owners since they have no residual claimants who can demand dividends. The personal profit motive and the incentive to maximize short‐run profits are consequently absent or at least muted (Willig et al., 2022).

Finally, regarding the questions of both ownership and ownership transparency in a strictly Danish context, there is limited scholarly work on either subject (Willig & BlachØrsten, 2022). Lund (1976) studied ownership and power regarding Danish public service as well as the effect of increased media concentration on media content (Lund, 2013). As part of the Media for Democracy Monitor, the reports by Willig and Blach-Ørsten (2017), Rasmussen et al. (2022), and Simonsen (2023) have focused on ownership transparency and concluded that threats to media transparency in Denmark are at a “medium” due to the lack of specific media law. The issue is covered by general law at both a national and European level (Rasmussen et al., 2022), and in practice, information about ownership is publicly available through The Central Business Register. The laws, however, only require transparency of private limited and cooperative companies if ownership exceeds 5% (Willig & Blach-Ørsten, 2017).

In the analysis, we focus on the following dimensions based on the Euromedia Ownership Monitor codebook and the projects’ methodology. As is stated under methodology: “the most important information in the EurOMo methodology pertains to the dimension of ‘Ownership structure’ and basically refers to legal shareholdings. Natural persons are considered beneficial owners, following the definition of the EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD, 2021)” (Euromedia Ownership Monitor, 2023). Regarding ownership, we focus on the legal structures of media outlets, allowing us to identify individuals and/or families that control news media (in contrast to structures that seek to hide actual owners, such as private foundations and family investment funds). Regarding transparency, we focus on the disclosure of direct and beneficial owners in the publications or websites of media outlets and disclosure about affiliation to external institutions (political parties, the Church, interest groups) in the publications or websites of media outlets.

This leads to the following three research questions (RQ):

RQ1: which types of ownership characterize legacy and new digital news media?

RQ2: how transparent is ownership in legacy and new digital media, especially in regard to beneficial owners?

RQ3: which types of information do the different news media disclose regarding information about affiliation to external institutions like political parties, the Church, and interest groups?

7. Methodology

As mentioned, this article is based on the methodology developed in the Euromedia Ownership Monitor project (Tomaz, 2024). A full description of the methodology can be found on the project homepage (https://media-ownership.eu/about/methodology/). However, this article only uses a small number of variables for its data collection as its focus is solely on ownership and ownership transparency. With regards to ownership, we first focus on types of ownership: for example, family businesses, cooperatives, trusts, for-/non-profit, public service, listed (stock market) companies, and national/international. Second, we focus on owner-affiliation with political parties, as well as national/regional Governments. While there are no specific laws on media ownership and media owner transparency, the Financial Statements Act says that all private limited and cooperative companies have to state all owners with more than 5% ownership. All ownership above 20% of the shares must be stated in the annual accounts. In Denmark, everyone can access the annual accounts of media companies, although there is a fee at the Central Business Register for some types of data (https://datacvr.virk.dk/), but most companies have the accounts on their annual reports on their website (Willig & Blach-Ørsten, 2017). All registration of ownership information, for the purposes of this article, took place during 2022.

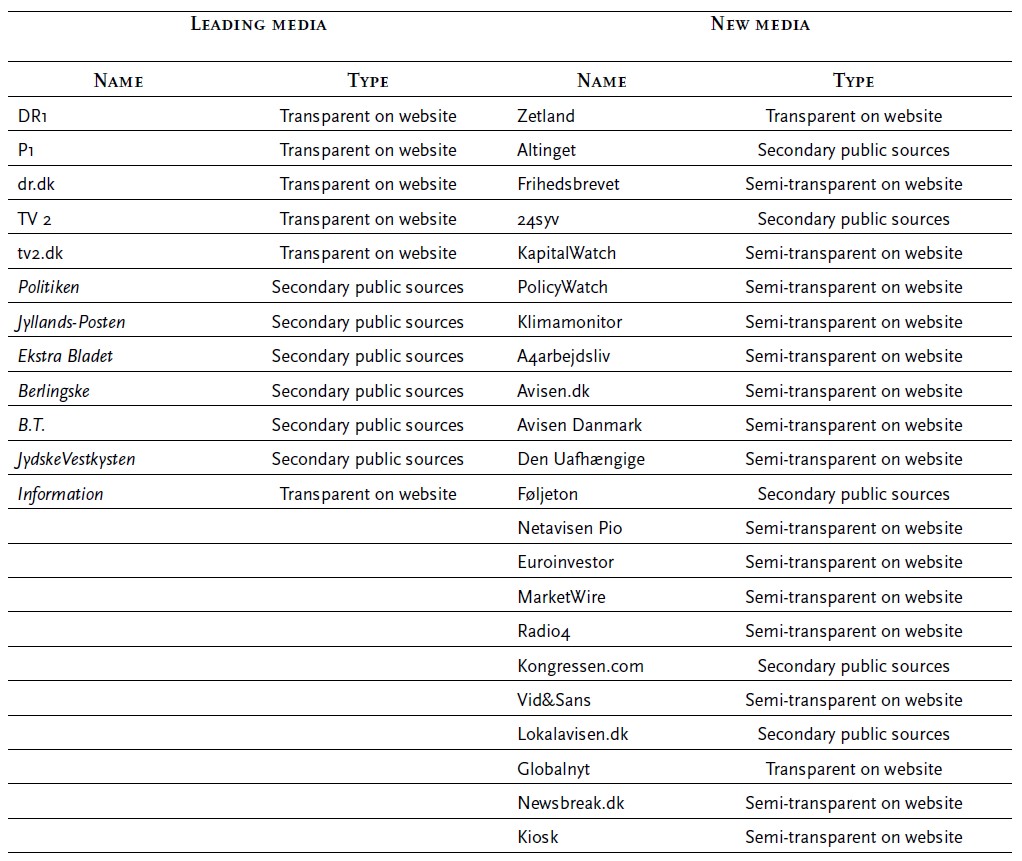

Regarding types of news media under investigation, we focus on leading, legacy news media and different types of digital, innovative, and alternative news media. The leading legacy news media are public service and legacy broadsheet newspapers (see also Blach-Ørsten et al., 2021), while the sample of alternatives aims also to mirror the many different types of news media that fall into this category. That is why while we have chosen 12 leading, legacy news media for the sample, the sample of alternative journalistic news media includes 22 news media. The selection of news media, both under the headline of “leading” legacy news media and the media under the headline “new media”, is based on a combination of audience reach and the wish to differentiate between the media types. For reach, we rely on the Danish data from the Reuters Digital News Report (Schrøder et al., 2022). For diversity, we rely on a list of all the new digital news media that have received Government support through the so-called “innovation pool” since 2014 (Slots- og Kulturstyrelsen, 2014), as well as studies on the use of new and alternative news media (BlachØrsten & Mayerhöffer, 2021; Mayerhöffer, 2021). We analyze a total of 34 Danish news media outlets, 12 legacy news media outlets, and 22 new digital news media outlets (see Table 1). The 12 legacy news media outlets include the two leading public service broadcasters, which encompass both radio, television, and online. We also include the leading broadsheet newspapers, leading tabloids, and one regional and one niche newspaper. The public services broadcasters, as well as the two tabloids, are the most used news media in Denmark online, reaching between 28% to 42% of the population in a given week, with different new digital media reaching just 1% (Føljeton) to 7% (Altinget) of the population, according to the Reuters Digital News Report (Schrøder et al., 2022).

Table 1 Overview of analyzed news media

Note. Overview of analyzed news media, including leading or new media indicated. Ownership affiliation indicated: transparent on the website = direct owner(s) and beneficial owner(s) are both mentioned in the publication/on the website; semi-transparent on the website = direct owner(s) in the publication/website but beneficial owner(s) requires secondary public sources; secondary public sources = access to secondary sources typically Central Business Register or annual fiscal report needed.

This means that in the list below, DR (Denmarks Radio), the leading Danish public broadcaster, is represented by three of their different platforms. Thus, DR1 is their leading television channel, P1 is the leading public service radio channel and dr.dk. is the leading online news site. The second public broadcaster, TV 2, is represented by their leading television channel, TV 2, and their online news site, tv2.dk. Also on the legacy list are the leading newspapers: broadsheet newspapers Politiken, Jyllands-Posten, and Berlingske; tabloid newspapers Ekstra Bladet and B.T.; regional newspaper JydskeVestkysten and the smaller intellectual newspaper Information.

The 22 new digital news media represent a broad sample of the kinds of digital news media that have emerged in Denmark since the 2000s and thus include a diverse range of media types from the niche political news media (Frihedsbrevet and Netavisen Pio) to more broadly accessible news media (Zetland, Avisen Danmark, Avisen dk., Altinget, Radio 4, 24syv), to news media concerned with the coverage of specific subjects like climate (Klimamonitor), finance (KapitalWatch, Euroinvestor, Marketwire), politics (PolicyWatch, Kongressen) to more innovative news media experimenting with form (Føljeton, Den uafhængige) or reaching a younger audience (Kiosk) or media focusing on science communication (Vid&Sans).

8. Analysis

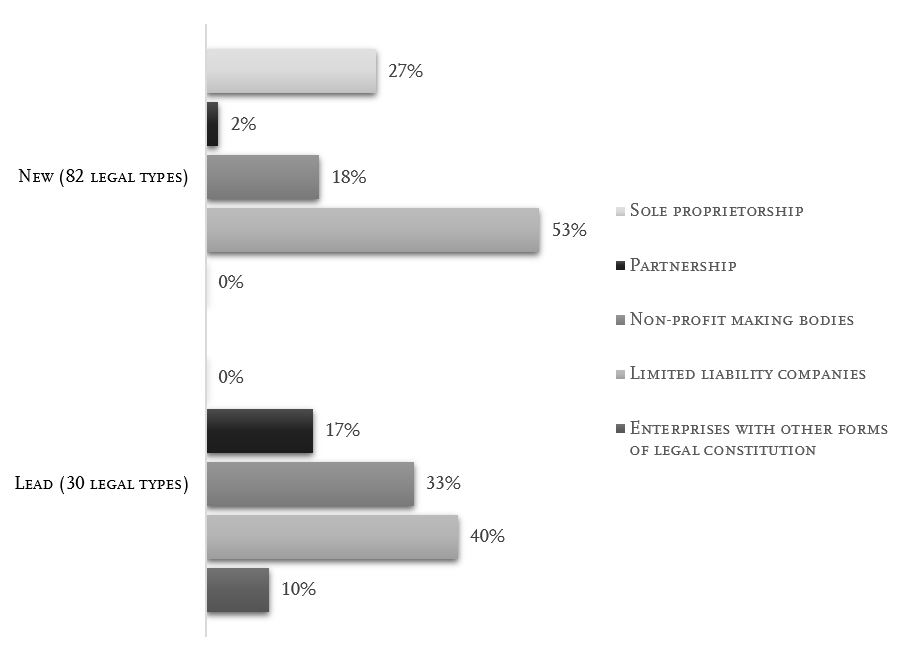

Turning to RQ1, the question of legal types of ownership, in Figure 1 below, we find both differences and similarities between the two types of news media. As in previous studies of news media ownership in Denmark, we find that ownership of legacy news media basically falls into two categories. Thus, regarding both print and the online market, private print news media is to a large extent owned by nonprofit foundations, while the public service news media that operate both offline and online are owned by the State (TV 2) or listed as self-owned in the case of Denmark’s Radio (Willig et al., 2022). One of the private media companies in the sample, Berlingske, is owned by a foreign media company in Belgium. However, the publishing rights are still owned by a foundation in Denmark. Regarding the new digital news media, their types of ownership show a good deal of variation. Thus, we find ownership by nonprofit foundations for a number of outlets (for instance, Globalnyt and Netavisen Pio), ownership by sole proprietors for another number of outlets, and ownership by a university-based publisher (Vid&Sans). However, limited liability companies own the largest number of outlets.

The largest difference regarding ownership between legacy news media and new digital media is that while sole proprietors own no legacy news media, this type of ownership is common when it comes to new digital news media. Looking further at beneficial owners in new and digital news media, in the case of Frihedsbrevet, ownership of more than 30% of the stock (in 2022) was tracked to a company in Luxembourg. This type of ownership has caused some media controversy, as Luxembourg is often associated with questions of tax avoidance (Schmidt & Sand, 2021). The chief editor of Frihedsbrevet also addressed the question of the home page of the news website (Brügger, 2021). Another major stock owner is a former partner of the Swedish capital fund EQT Partners, known for its investment in many different types of businesses, such as aviation, toys, and hotels (Olsen, 2023). Regarding threats of media capture by ownership, these threats differ according to ownership type. Thus, private nonprofit foundations, a typical Danish ownership type, are not mentioned in studies of media capture, though Benson (2017) focus on capture by philanthropic foundations. Private ownership by a sole proprietor (media entrepreneur) is, however, often associated with the risk of media capture by individuals with strong agendas, either political- or business-wise. This type of ownership is not found in legacy news media but only in digital news media, showing a clear change in the types of media ownership that are present in the Danish media system. Regarding media capture of public service, there has been no change in ownership structure in Danish public service news media nor in the public service contracts. However, political pressures and hostility do exist in the case of DR (Dragomir & Aslama Horowitz, 2021), mostly surfacing as financial pressure on the institution, as in 2018 when a center-right Government supported by a right-wing party cut the budget by 20% resulting in closures of a string of programs as well as lay-offs (Holtz-Bacha, 2021).

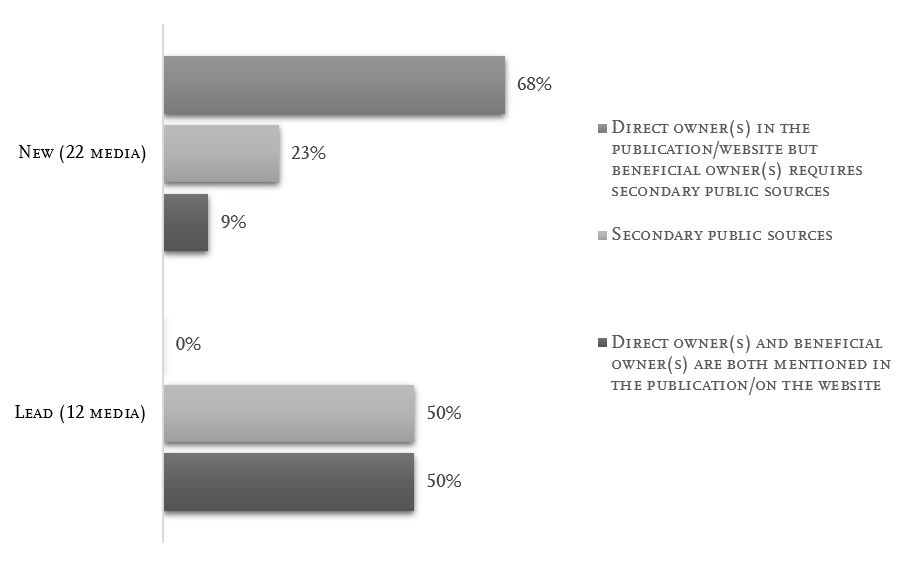

Regarding RQ2, the disclosure of ownership on homepages, as well as the transparency of direct owner/beneficial owner (see Figure 2), we again find a number of differences between legacy news media and new digital news media. Regarding transparency, we found that for the two public service broadcasters in the sample, both direct owners and beneficial owners are mentioned on the website. Regarding legacy print/online news media, we find, with the exception of the niche paper Information, that in order to find both the direct and beneficial owner, you have to visit both the website of the publication as well as one secondary public source (the Central Business Register). Regarding the new digital news media, the picture is slightly different. While the transparency of the direct owner is visible on the websites of the different news media, finding out who is the beneficial owner requires more work, most often a combination of reading the news media’s yearly reports and checking information against the Central Business Register.

Though the Central Business Register is, as it says on the home page, the “government’s master register of information about businesses in Denmark and Greenland”, we found that for several of the new digital news media, information was either missing or not completely up to date. Thus, for one owner, Advice Netværk A/S, the latest update on the number of staff was from 20141, while for another owner, the information was last updated in 20192. As for the foundation-owned online newspaper Netavisen Pio, information on the Central Business Register is spare regarding ownership3, though the names of the board members, not owners, can be found on the home page. The only description of the people behind the foundation is mentioned on the home page, where they, in vague terms, are described as “a group of people who share the conviction of wanting to bring more nuance to the public debate”4. This also means that foundation ownership can be used to obscure ownership. Though this exact type of ownership form, in relation to news media ownership, is often highlighted as a way to guard against undue financial pressure, it may not work as well if the foundation has other aims that may be more political.

The head of the board of Netavisen Pio, Max Meyer, is not identified on the home page by anything other than his name. However, in an article on the newspaper’s home page regarding the treatment of Jews in Denmark, he is mentioned as both a former union representative of the plumber’s union (Friedberg, 2020) and the head of the board of the online newspaper. The other board member, Jakob Sand Kirks, is the founder and owner of his own communication and lobbying company, Sand Kirk (https://sandkirk.dk/). Thus, while the Central Business Register is highlighted in the Media Pluralism Monitor reports on Denmark (Rasmussen et al., 2022; Willig & Blach-Ørsten, 2017) when looking into ownership of new, digital news media, the database is not always up to date, nor enough of a transparency window as to give the full transparency of ownership of a registered company or business.

Finally, turning to RQ3 and the question of transparency regarding owners’ affiliation to external institutions like political parties, the Church, or interest groups, we find no transparency on these issues. Again, this is due to the lack of a specific media law regarding ownership and the lack of political focus from Danish media politicians. However, as already mentioned in this article, some owners of new digital news media are or have been active in politics, while others have been associated with special interest organizations or think tanks. Thus, one of the stockholders of Frihedsbrevet has previously donated money to the center-right political party, Liberal Alliance (Albrecht, 2021), while another of the stockholders has previously been chair of the board of a center-right think tank (Bjørn Høi Jensen ny Bestyrelsesformand i CEPOS, 2012). Adding to that, the recent example that also opened this article of a mayoral candidate who owns 11 different local newspapers in his company raises the obvious question of how this ownership could affect content in line with political convictions or alliances. In other words, RQ3 shows that the new ownership forms registered in RQ1 do lead to a risk of media capture by owners or investors with political agendas.

9. Conclusion: From Dual Ownership to Multi-Ownership

Traditionally, ownership in Denmark is described as a form of “dual” ownership, with public broadcasters being owned by the State or self-owned and the private news media outlets being owned by foundations or by a publicly traded company. This has always been a slightly reductionist description but is now clearly no longer a valid way to describe ownership forms in Denmark. Also, traditionally, ownership transparency in Denmark is described as high. This is now also a statement that needs to be updated. Indeed, this article brings several nuances to the understanding of ownership in the Danish media system. Since the beginning of the 2000s, an increasing number of digital-native news media have sprung up in the Danish media system, helped along by digitalization, but also some from 2014 by Government policy favoring so-called “innovation subsidies” with the intent to support new kinds of news media whether online or in print. Based on new analytical parameters developed as part of the European Media Ownership, our sample of news media includes both legacy news media and new digital news media. All in all, we analyze 34 Danish news media outlets, 12 legacy news media outlets, and 22 new news media outlets, focusing on types of ownership and ownership transparency.

Regarding RQ1, we find that private Danish legacy print media is mostly still owned by nonprofit foundations, while legacy public service news media are owned by the State or listed as self-owned. Regarding new digital news media, we find a greater variety of ownership forms, some with private owners, some owned by foundations, and some owned by sole proprietors. However, only new digital news media have ownership by a sole proprietor. Private ownership by a sole proprietor (“media entrepreneur”) is associated with the risk of media capture by individuals with strong agendas, either political- or business-wise. This type of ownership is not found in legacy news media but in digital news media, showing a clear change in the types of media ownership that are present in the Danish media system. Regarding RQ2, we find that transparency of direct and beneficial owners is more accessible in legacy news media than in new, digital news media. We also find that while the Central Business Register, in other analyses of news media ownership in Denmark, is highlighted as being very efficient with respect to securing ownership transparency, in our study, this is not always the case. This is, however, mostly the case regarding new digital news media. Thus, we find outdated information regarding some of the owners of new digital news media, while we also, in one case, find little transparency regarding ownership by a foundation. In other words, the new ownership forms found amongst digital news media are more opaque than the ownership forms in legacy news media. Finally, regarding RQ3, we find that there is no tradition in the media industry of publishing the “natural persons” possible affiliations to either political or other commercial interests. The last part is especially relevant, as new digital news media outlets, unlike legacy media outlets, are sometimes owned and funded by private investors primarily active in other industrial fields or politics. This ownership often carries the risk of media capture, which has been more commonly associated with less established media markets. Lack of full transparency regarding owners’ political ambitions, connections, or affiliations can leave audiences unaware of the potentially biased nature of the news they consume.

In sum, the article shows that while the Danish media system is one of the more stable democratic corporatist media systems, some of the changes that have affected other media systems are also beginning to manifest here. Thus, the traditional dual ownership is now better characterized as multi-ownership, with new types of ownership forms emerging with digitalization, alongside new challenges, such as the risk of ownership capture. The traditionally high transparency of the system now includes more opaque ownership forms, where beneficial owners are less transparent and where owners’ links to other financial or political interests are left unaddressed by current media policy. Indeed, the case study shows, much as Nielsen (2017) suggested, that digitalization will bring changes in ownership structure that will entail the risk of capture by ownership, even in more stable media systems. As mentioned, there are no specific laws on either news media ownership or transparency of news media ownership in Denmark, and the last media policy agreement from 2023 does not address the issues (https://kum.dk/kulturomraader/medier/medieaftaler). The agreement does address the innovation subsidies given since 2014, to some degree, to new digital news media, but questions of ownership and innovation subsidies are not raised in the agreement. Indeed, media policy is not changing at the same pace as the media systems, and the emerging changes and challenges described in this article so far seem invisible to the Danish media politicians.

texto em

texto em