Did you know that memes have become a powerful tool for social movements, inspiring mass protests, and influencing public opinion? In recent years, thanks to the ubiquity of social media platforms and the rise of memes, digital activism has emerged as a game-changer in political engagement. On the one hand, memes are humorous images, videos, or pieces of text that are copied and spread rapidly online, often with slight variations (Milner, 2012; Shifman, 2014). As memes serve as accessible and relatable tools for engaging a broad audience, they are particularly effective in contemporary social movements (Fahmy & Ibrahim, 2021; Lalancette et al., 2020; Lukács, 2021; Moreno-Almeida, 2021; Moreno-Almeida & Gerbaudo, 2021). By analyzing them within the context of Romanian social movements, this study highlights how these digital artifacts contribute to the public discourse of the movements, challenge dominant narratives, and even promote alternative visions. This subject brings novelty to the online social movements domain because it underlines the unique role of memes-a relatively under-examined aspect of academic literature. At the same time, the relevance of this subject lies in its ability to shed light on the transformative potential of digital culture in terms of political and social engagement.

Online social movements

Online social movements are powerful because people use digital media and Internet connectivity to drive change. Edwards, Howard, and Joyce (2013) explained that these movements leverage digital tools for quick, adaptable responses to events, enabling coordination across regions and time zones (George & Leidner, 2019). Consider the following: smartphones, tablets, and laptops are essential for activists, providing real-time updates and helping them organize and communicate effectively (Bennett & Segerberg, 2013; Choursia & Suri, 2020; Garrett, 2006; Papacharissi & Oliveira, 2012; Poell & van Dijck, 2015). Garrett (2006) suggested that these tools can make traditional hierarchical organizations less important. Simultaneously, social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram are vital. They disseminate information, foster communities, and maintain engagement (Papacharissi & Oliveira, 2012; Poell & van Dijck, 2015; Tufekci, 2017). Bonilla and Rosa (2015) highlighted how Twitter documents and challenges police brutality and racial injustice, which can establish shared political temporality.

However, there are challenges. The need for digital skills and balancing multiple connections can exclude those without access to technology or reliable Internet (Rainie & Wellman, 2012). The anonymity of the Internet can lead to accountability issues and misinformation spreading (Boyd, 2014; Castells, 2012; Milan, 2013, 2015). That is why Tufekci (2017) added that online movements often lack organizational depth, face decision-making difficulties, have tactical limitations imposed by platforms, must evade censorship, and deal with the unpredictable outcomes of new technologies.

Memes and Online Social Movements

Online social movements use digital tools like social media campaigns, hashtag activism, and online petitions to engage people (Edwards et al., 2013; George & Leidner, 2019; Joyce, 2010; Mutsvairo, 2016). In this virtual “game,” memes convey complex ideas in a funny and accessible manner (Milner, 2012; Shifman, 2014). As a result, such media creates new narratives (Gal et al., 2016). For example, The Pepper Spray Cop meme criticizes democratic governance in various historical and cultural contexts, challenging dominant narratives (Milner, 2013).

In social movements, memes help mobilize collective action and create a sense of community among diverse groups (Daphi, Le, & Ullrich, 2013). They allow individuals to relate personally to political messages and express ideologies related to nationalism, identity, and ultranationalism. By making opinions easy to share and understand, memes offer a new way for people to participate in democracies (Lukács, 2021; Moreno-Almeida, 2021; Moreno-Almeida & Gerbaudo, 2021). Moreover, the speed at which memes spread often surpasses that of traditional media, enabling them to blend entertainment with serious commentary to engage and mobilize people quickly (Denisova, 2019; Nissenbaum & Shifman, 2018). Their emotional impact makes them shareable, amplifies their reach (Wiggins, 2017), and transforms them into powerful tools for shaping public discourse (Fahmy & Ibrahim, 2021).

Methodology

Framing theory, as articulated by Benford and Snow (2000), focuses on how social movements construct meaning to mobilize support, sustain participation, and achieve their goals. We apply it to understand how memes function within Romanian social movements by addressing three core framing tasks: (a) diagnostic framing, which involves identifying problems and attributing blame or causality (helps to pinpoint what is perceived as the main issues and who or what is responsible for these problems), (b) prognostic framing, which suggests solutions and strategies to address the identified problems (outlines a plan of action), and (c) motivational framing, which provides a rationale for action (aims to motivate and encourage people to join the movement by highlighting the moral, emotional, or practical reasons for getting involved). Starting from this, we will primarily search to answer the following research questions: (1) How do memes highlight specific issues and assign blame, using cultural and historical references to build narratives around social movements or the problems faced by them? (2) What role do humor and satire in memes play in the diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing of Romanian social movements? (3) What differences can be observed in the framing strategies of memes across various so-

cial movements in Romania (e.g., environmental vs. anti-corruption movements)?

Selection of Romanian social movements

The selection of the major social movements in Romania was defined by the number of participants (minimum 100,000) and the coverage area (at least 15 cities). For instance, the Roșia Montană protests occurred in 50 Romanian cities and 30 abroad (Besliu, 2021). At its peak, the movement gathered around 200,000 people only in Bucharest (Niculescu, 2019, p. 44). Facebook groups and online communities like United We Save, United We Change, and United We Save Roșia Montană were primary means of communication through which diverse messages and information were disseminated (Patrut & Stoica, 2019, p. 217).

Later, the Colectiv nightclub fire in 2015 was followed by protests all over the country, reaching a peak of 30,000 participants in Bucharest alone and 100,000 nationwide (Cretan & O’Brien, 2020, pp. 375-376). The protests occurred in major cities in Romania, such as Bucharest, Constanta, Timisoara, Iasi, Cluj, Craiova, Galati, Sibiu, Brasov, Bacau, and Ploiesti, as well as in some international cities like Birmingham, Graz, London, Paris, Dublin, Rome, and New York (Cmeciu & Coman, 2018, p. 13; Sutu, 2018, p. 101). It is also noteworthy that following the 2015 protests, the Facebook group and online community were established, serving as vital tool for rallying support for subsequent protests. Consequently, the anti-corruption protests (#RESIST) were coordinated by this group and took place in over 45 cities in Romania and abroad (Pătruț, 2017, pp. 43-46; Gubernat & Rammelt, 2017). The number of participants peaked in February 2017, at approximately 600,000 people (Crișan, 2018, p. 186).

Lastly, despite the small number of reported participants, we included the MarchApril 2021 anti-restriction protests because they occurred in over 24 Romanian cities, including Bucharest, Sibiu, Iasi, Cluj, Galati, Brasov, Constanta, Timisoara, Ploiesti, Tulcea, Focsani, and Braila (Popescu, 2021; Weident, 2021; Proteste În Țară Față de Noile Restricții Anti-COVID, 2021). These protests were part of an international wave of protests and therefore required special attention.

Overview of selected social movements

Since 2013, the Roșia Montană issue has sparked significant debate in Romania, leading to the formation of two opposing factions: proponents of the Roșia Montană Gold Corporation’s mining project and opponents, particularly those concerned about the use of cyanide in mining (Chiţu & Albu, 2013, p. 99; Maxim, 2013). On September 16, 2013, the Zelist website documented 9,940 references to the subject within 24 hours, reaching approximately 12 million users. Within a week, the number of references increased to 58,362, garnering an estimated 79 million views (Discutiile Din Online Despre Roșia Montană Continua: 10 000 Mentionari in 24 de Ore, 2013). The level of engagement was substantial, and the prevalence of the online platform provided individuals with a platform for unrestricted expression.

In 2015, a Colectiv nightclub fire led to spontaneous demonstrations. Social media platforms, particularly Facebook, played a key role in organizing these protests (Creţan & O’Brien, 2020, p. 376). Euronews referred to these demonstrations as the CTRL ALT DEL Revolution (Bonea, 2015). Protesters adopted this term to advocate for a resumption of Romania’s political and social landscape, and they were labeled as the generation of Facebook by the media (Grigoriu, 2016, p. 34). Individuals shared images featuring protest signs accompanied by hashtags like #Colectiv, #ResetRomania, and Ctrl + Alt + Del, along with slogans such as “Down with corruption” and “We want hospitals, not cathedrals” (Cmeciu & Coman, 2018). These actions attracted a diverse range of participants, including students, seniors, and various organizations (Creţan & O’Brien, 2019). The Facebook group “CorruptionKills” had approximately 890 active members and 10,421 followers at that time, indicating significant involvement (Pătruț, 2017, p. 43).

In 2017, protests in Romania again gained international attention. Following the parliamentary elections in December 2016, the Social Democratic Party proposed pardoning certain crimes and amending the Penal Code, leading to the largest wave of protests in 25 years (Gubernat & Rammelt, 2017, p. 1). Facebook and emerging communities such as #REZISTENȚA and #REZIST facilitated the mobilization of individuals (Florescu, 2018). On February 1, 2017, more than 150,000 people gathered in Victory Square, Bucharest, to protest the modification of the criminal code (Cel Mai Amplu Protest Din Ultimii 25 de Ani. Peste 300.000 de Oameni Au Fost În Stradă, 2017). The discourse promoted the idea of a “new Romania,” especially by adopting a strong anti-government position, as evident in slogans like “In a democracy, thieves are in prison”, “Down with the governments” or “Down with the government,” and “Romania, wake up” (Borțun & Cheregi, 2017, pp. 19-20). By February 5, the protests had attracted over 600,000 participants, marking a memorable moment in Romania’s history. The protests spread to more than 81 cities across 36 countries, highlighting global solidarity against corruption (Adi, 2017, p. 53).

In March 2021, a notable increase in anti-restriction demonstrations occurred subsequent to the enforcement of new COVID-19 regulations. The government’s imposition of restrictions in response to the escalating number of COVID-19 cases incited protests in Bucharest and other major urban centers (Coman, 2021). Independent senator Diana Șoșoacă gained prominence during these protests, particularly through her rendition of Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall” (Senatoarea Șoșoacă Face Show La Protestul Antimască Din Piața Victoriei Pe Piesa “Another Brick in the Wall” de La Pink Floyd, 2021).

Data collection, selection criteria, and analytical framework

The images were gathered from Internet databases and specific Facebook meme pages with varying numbers of followers, such as Junimea (about 1.2m followers), Mielul Sfânt (Holy Lamb) (61K), Goovernu Rumeniei (Romania’s Government) (56K), and Jandarmemeria (43K). The selection of meme pages was based on the follower count (+43K). Keywords like Roșia Montană memes, Save Roșia Montană memes, colectiv memes, colectiv fire memes, corruption Romanian memes, Rezist memes, #rezist memes, anti-restriction protest memes, and COVID protest memes were used in the search engine. For meme-focused Facebook pages, single keywords (without “memes”) were used. Google Image Search was chosen for Internet database searches due to its popularity and high display rate. Image searches relied on accurate image descriptions for successful results; missing descriptions could cause search engines not to find images.

This research focused on image macro memes, which are the predominant type found in Romanian digital spaces (Ungureanu, 2022). Data were collected from the Facebook database based on the descriptions provided. Memes were categorized according to visual elements, which included textual components and visual symbols such as logos and images depicting gendarmes or protesters. In the results section, out of the 46 memes collected, we illustrated and analyzed 18 memes that directly referenced the protests (e.g., using keywords like “save,” “against,” campaign logos, protesters) and were posted during the period of the social movements.

We conducted a qualitative analysis employing deductive methods grounded in the pre-defined categories of Benford and Snow’s (2000) core framing tasks. Specifically, for diagnostic framing, we analyzed how memes identified particular issues and allocated blame through the use of cultural and historical references. In terms of prognostic framing, we examined the solutions and strategies depicted in memes, with a focus on the interplay between textual content and visual elements. Finally, for motivational framing, we examined how humor and emotional appeals were used in meme-making to stimulate engagement.

Results

Roșia Montană

As the earliest and most popular meme pages in the local digital environment, Junimea and Omu Paiangăn emerged in 2012-2013 and 2014, respectively, in the case of Ion Creangă’s page. The meme creators, who were likely minimally active or inactive during the period, did not feature the Roșia Montană protests. Thus, all the memes gathered were sourced from the Google Images search engine. Out of 7 collected memes, only 5 were selected for illustration due to their direct visual and textual references.

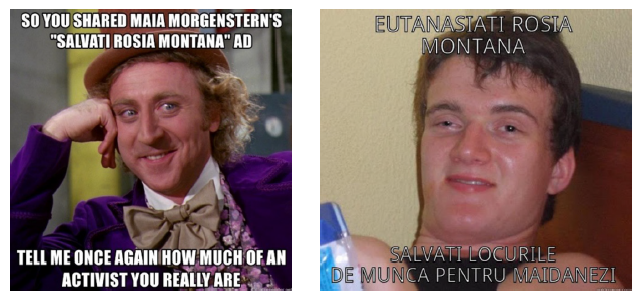

The first meme features the “Condescending Wonka” framing, which originated in 2011. In June 2012, a commercial starring Romanian actress Maia Morgenstern was released (Necula, 2012). The meme we are examining combines elements from both sources: it uses Wonka’s image and includes a textual reference to the commercial. This suggests that the meme was created and shared later on. Additionally, through the cross-reference, the meme critiques the confusing nature of digital activism with the message, “Tell me once more how much of an activist you really are.”

Figure 1 Memes about Roșia Montană (approx. 2013). Sources: memegenerator.net, quickmeme.com. Captions: Right “Euthanize Roșia Montană save the jobs of the stray dogs”

According to KnowYourMeme.com, “How high you are? Yes” meme appeared on the Internet in December 2011. In our example (Figure 1, right), the meme includes text in Romanian. On the top, the text states “Euthanize Roșia Montană,” and on the bottom, “Save the jobs of the stray dogs.” Linking popular culture to politics and identity to current events-the stray dogs’ problem in Bucharest (circa 2013) (Dadacus, 2013) and the Roșia Montană Campaign-as Milner previously pointed out while dissecting the memescape (2012, pp. 72-79), both memes are setting milestones in terms of interdiscursivity (the interaction and overlap between different discourses or ways of communicating about particular topics).

Although it originally served as a motivational poster, the Keep Calm slogan was readapted to the Internet age and became a full-fledged meme. The visual architecture and format of the Keep Calm poster are mobile elements that provide intertextual recognition by connecting it with previous image productions, while textual adjustments redirect memes to a specific audience (Milner, 2016; Varis & Blommaert, p. 37). The “Save Roșia Montană” logo has been transformed and recontextualized into a “Keep Calm” poster (Figure 2). The poster format offers intertextual recognition, while simultaneously aiming at an audience concerned with and/or interested in the subject of Roșia Montană’s exploitation.

The Annoyed Picard’ Roșia Montană version (Figure 3, left) is an image macro featuring a screen capture of the “Star Trek: The Next Generation” character JeanLuc Picard, whose exasperated expression and captions reveal his frustration or incredulous reaction: “How the f**k Ghita the Shepard has more likes than Save Roșia Montană.” The meme introduces a Romanian social media influencer (“Ghiță the Social Shepard”) and translates the campaign’s message to potential Star Trek or Patrick Stewart fans.

By contrast, another Roșia Montană meme was created by using a picture of a noname character, most likely a hippie present at a random protest, and captions that say that “she is against Roșia Montană gold exploitation, yet she supports Băsescu” (Figure 3, right). The Knowyourmeme website names the image macro “College Liberal”

Figure 2 Left: Graffiti “Save Roșia Montană,” from Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Source: blogs.ed.ac.uk. Right: Keep Calm meme/poster. Source: ro.pinterest.com

and states that it “portrays the character as a naive and hypocritical left-wing political activist, referencing various clichés associated with the hippie subculture.” (College Liberal, 2011) Thus, the meme emphasizes that some protesters are foolish enough to oppose mining yet support one of the main advocates of the project (Romania’s former President Traian Băsescu).

Figure 3 Left: Annoyed Picard Roșia Montană Meme. Source: memegenerator.net. Right: Local Hippie Roșia Montană meme. Source: quickmeme.com. CAPTIONS: Left “How the f**k Ghita the Shepard has more likes than Save Roșia Montană.” Right “She’s against Roșia Montană exploitation/She supports Băsescu”

Analysis of memes related to the Roșia Montană protests revealed underutilization of diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing. Despite their potential, memes such as “Condescending Wonka” and “College Liberal” fail to robustly diagnose issues or effectively attribute blame. The “Condescending Wonka” meme, which mocks superficial digital activism, does not sufficiently highlight the environmental and social stakes of the Roșia Montană exploitation. Similarly, the “College Liberal” meme critiqued the protesters’ perceived hypocrisy without addressing the core issues or providing a solution. Prognostic framing is weak, as the memes did not suggest actionable solutions or strategies to address the mining project. The “Keep Calm” poster, although visually impactful, lacks depth in outlining a clear action plan. Memes should provide more substantial guidance regarding the movement’s goals and tactics. Motivational framing is also limited. The memes often rely on humor and satire without effectively inspiring collective action or emphasizing the moral imperatives of the movement. For instance, the “Annoyed Picard” meme, which juxtaposes the popularity of an influencer with the Save Roșia Montană campaign, fails to offer a compelling call to action.

Colectiv nightclub fire

We collected 10 memes about the Colectiv nightclub fire protests. Of these, 7 were from Google Images and 3 from Facebook. All memes from Google Images and one from Facebook did not meet our criteria. The two remaining memes used a representative image of the Colectiv protest: a lighted candle on a black background, which was suitable for illustration. The first was published by Junimea in January 2016, about two and a half months after the fire, announcing “a moment of silence for the pupils who still have exams” (Figure 4, left). The one on the right was distributed a couple of days later by the same page and stated that “as a sign of solidarity, all the pupils in Romania will not go to school on Monday.” Using the candle on a black background, the memes confirm Shifman’s theories regarding the awareness of previous variants of the image (Shifman, 2014, p. 177): the representative image of the campaign initiated after the Colectiv nightclub fire. Thus, the meme creators were aware of the existence of this image and its significance. In this way, the image has been recontextualized for another purpose, although in the background, the previous version is always indicated.

Figure 4 Colectiv nightclub Fire memes (11/17.01.2016). Source: facebook.com/www.juni.ro. CAPTIONS: Left “A moment of silence for the pupils who still have exams.” Right - “The pupils in Romania are together with their peers from Bucharest. / #SchoolsofBucharest / As a sign of solidarity, they will not go to class on Monday either”

These two memes demonstrate a better use of framing, particularly in diagnostic and motivational aspects. The use of the lighted candle symbol efficiently diagnoses the tragedy and attributes blame to systemic failures. However, the recontextualization of this symbol in humorous memes about school exams dilutes its impact, with the potential to undermine the seriousness of the protest message. Prognostic framing is again minimal. The memes do not offer tangible steps to prevent future tragedies or to hold responsible parties accountable. This gap reduces the movement’s potential to mobilize support for long-term systemic change. On the other hand, motivational framing shows some strength, as memes evoke solidarity and collective mourning. However, the potential to stimulate sustained action is limited by memes’ focus on humor and short-term sentiments rather than enduring commitment.

#Resist

With the #RESIST protests, the meme creators did not remain indifferent to topics passionately debated offline, let alone online, and they remixed or incorporated images and suggestive text to support or criticize actions in the street. Even so, considering the long time interval (2017-2020), the search results were low: 12 were from Google Images and 7 from Facebook. Of these, only 3 from the first source and 2 from the second fulfilled the stated criteria by making direct references, by text or image, to protests.

The memes present different perspectives on the protests, from the government to neighbors and romantic interests’ to reframing the gloomy reality or favoring procampaign views (preferences for civic initiatives define a speed dating outcome: “What do you tonight?”, “Going to the protests,” “She’s the one”) (Figure 5, left and middle). At the same time, the Facebook platform was filled with memes featuring a gendarme. The photo used in the memes was taken by journalist Dragoș Sasu and illustrates a gendarme sitting on a chair during the August 10 protests in Victory Square. The picture was immediately distributed, in several versions, on social media, becoming viral in a very short time (Figures 5-right and 6). The gendarme becomes the target of ridicule of any kind, from mom to self-deprecating jokes, while ensuring the repetition and recurrence of an image directly linked to a current event; it could be interpreted as a means of promoting the social movement. Hence, they are reminiscent of the theories of Wiggins and Bowers (2015) and confirm that the memescape is part of digital communications that allow the instant upload of all kinds of images and their personalization, as described by Papacharissi, Oliveira (2012, pp. 8-9), Poell, and van Dijck (2015, p. 553).

This time, memes about the protests exhibit a varied approach to framing, with some success in all three core framing tasks. Diagnostic framing appears in memes that critique government actions and highlight protesters’ perspectives. However, the use of humor, such as in the “gendarme on a chair” memes, while effective in capturing attention may trivialize the protest’s seriousness. Prognostic framing is sporadic. Memes like the speed-dating one (“What are you doing tonight? Going to the protests”) failed to outline specific strategies or solutions. More emphasis on actionable plans and clear objectives could enhance the movement’s effectiveness. Then again, motivational framing is relatively robust, with memes encouraging participation and solidarity. The recurring image of the gendarme, for instance, reinforces the protesters’ narrative and promotes unity. Though, then again, the focus on mockery might alienate some potential supporters who view the situation more grimly.

Figure 5 Left: #Rezist protests meme (me.me). Middle: #Rezist protests meme (05.11.2017, facebook.com/www.juni.ro). Right: #Rezist Gendarme meme (12.08.2018, facebook.com/ www.juni.ro.). CAPTIONS: Left “Protests 2017 / What I think I’m doing / What the Government thinks I’m doing / What my retired neighbors think I’m doing / What my dog thinks I’m doing / What my girlfriend thinks I’m doing / What am I doing.” Middle: “What are you doing tonight? / Going to the protests / She’s the one.” Right “Waiting for the protesters to be discharged from the hospital to beat them again”

COVID-19 restriction

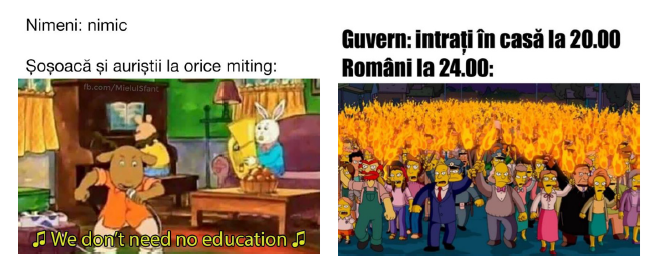

In the case of the COVID-19 protests, we identified a very small number of memes, only in the databases of the Facebook platform. The meme distributed on the Holy Lamb on March 24 directly references to this protest and criticizes the intellectual credibility of the participants (“Șoșoacă and her AUR gang”) by inserting the double negation used by Pink Floyd (“We don’t need no education”) (Figure 7, left). A few days later, on March 29, the Romanian government published a meme expressing anti-restriction views (Figure 7, right). This meme also illustrates a procession of protesters with burning torches. In the case of these two memes, we can also clearly see the cross-references to TV productions dedicated to children and young people, respectively, the animated series Arthur and the Simpsons, as well as to musical culture by evoking the lyrics of Pink Floyd.

Figure. 7 Left: Anti-mask protest meme (Mielul Sfânt, March 24, 2021). Right: Anti-restriction protests meme (Goovernu rumeniei, March 29, 2021). CAPTIONS: Left - “Nobody: nothing” / “Șoșoacă and her AUR gang (party members) at any protest.” Right - “Government: get into your homes at 8 pm / Romanians at midnight”

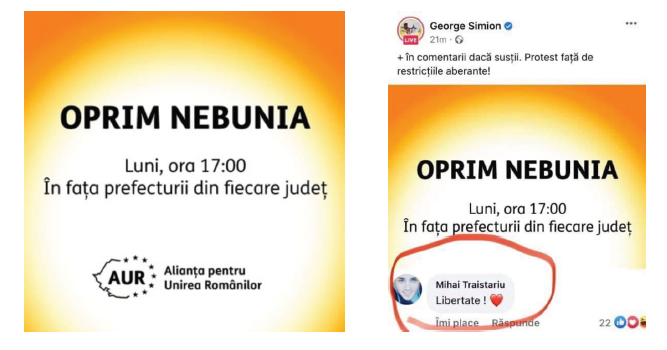

In the comments section of the right image in Figure 7, we found a comment by a user (Figure. 8, left). The comment urges participation in a protest organized by the AUR party, which was previously distributed by party leader George Simion. In the same evening, the Goovernu Rumeniei page turned Simion’s post into a meme (Figure 8, right). The meme is a screenshot type that includes Simeon’s post and a highlighted comment by Romanian singer Mihai Trăistariu. The comment that exclaimed “Freedom!” and ended with a heart emoji could have been posted by the owner of a fake account. Real-time meme creation/ production and distribution confirm Daphi, Le, and Ullrich’s (2013) statement that images involved in social movements can be presented and represented globally instantaneous.

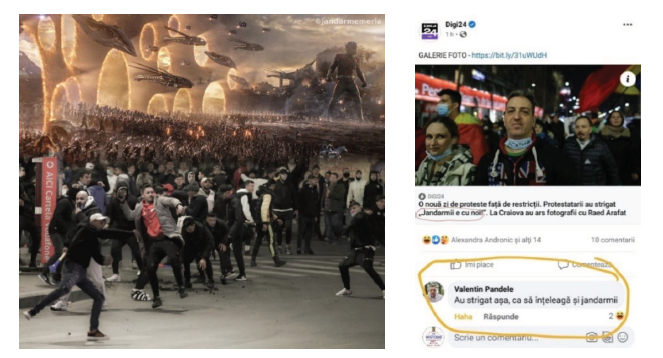

In the same activist tone, the Jandarmemeria page featured, on March 30, a meme described by the text “out with the virus from the country.” The post is a digitally edited image of protesters and, in the background, a screenshot from the movie “Avengers: End Game” (Figure 9, left). On the next day, the Goovernu Rumeniei page distributed a meme that included a screenshot of a news report from Digi24: “A new day of restrictions Protesters shouted, «The gendarmes is with us!». In Craiova, they burned photos with Raed Arafat” and the comment of a user (Figure 9, right). In addition to taking the screenshot, the creator of the meme highlighted the sentence “The gendarmes is with us!” from the Digi24 news report and a comment from user Valentin Pandele, who claims that the protesters “shouted like that so that the gendarmes would understand.”

Right: “George Simion” meme (Goovernu rumeniei, March 28, 21, 10 am and 9 pm). CAPTIONS: Left - “We stop the madness / Monday, 5 pm / In front of the prefecture from each county / AUR / THE ALLIANCE FOR THE UNION OF ROMANIANS.” Right - “+ in comments if you support. Protest against the aberrant restrictions / We stop the madness / Monday, 5 pm / In front of the prefecture from each county / Mihai Traistariu: Freedom!”

Figure 9 Left: Meme anti-restriction protests (Jandarmemeria, 30.03.21). Right: Meme anti-restriction protests (Goovernu rumeniei, 31.03.21). CAPTIONS: “A new day of restrictions Protesters shouted: «The gendarmes are with us!». In Craiova they burned photos with Raed Arafat”/ “They shouted like that so that the gendarmes would understand”

Memes addressing the COVID-19 restriction protests were limited in number and impact. Diagnostic framing is present, but it often conflates various grievances without clearly attributing blame or defining the issue. For instance, memes criticizing the participants’ intellectual credibility using Pink Floyd’s lyrics do not adequately address the complex motivations behind the protests. Prognostic framing is nearly absent. The memes do not propose viable alternatives to the restrictions or ways to balance public health and individual freedoms. This omission weakens the movement’s potential to present itself as a rational and organized force. Motivational framing suffers from a similar issue. While memes like the digitally edited frame from “Avengers: End Game” engage viewers, they do not provide a compelling call to action. The reliance on humor and pop culture references may detract from the seriousness of the protests and fail to inspire sustained engagement.

Conclusions

With a focus on meme efficiency through the lens of framing theory, this study highlighted the nuanced role of memes in Romanian social movements. To the first question, more specifically, (1) on how do memes spotlight issues and assign blame to build narratives around social movements, we can say that no acute mobilization was observed to distort the dominant narratives, and, from a particular perspective, the memes about the anti-restriction protests tried to closely reproduce the situation on the streets. We mention here Senator Șoșoacă singing in the street, an angry mob carrying flaming torches, and protesters throwing stones. Although the protesters were not in any number of days or locations in such large numbers as those depicted by the memes, nor did they have flaming torches, they were enraged and threw stones, bottles, and firecrackers at law enforcement.

On the other hand, by connecting current events to mainstream and digital culture, Willy Wonka and Captain Picard debated the subject of Roșia Montană and associated it, perhaps inaccurately, with alcoholism, drug addiction, and hippies. Accordingly, a meme about the Colectiv nightclub fire spread false information, such as a possible day off in solidarity with the victims, and those with the gendarme in Victory Square, although his figure was not recontextualized as in the case of the PSC analyzed by Miller, offered in return different voices to the same silent, motionless character, voices that might have distorted his true intentions and/or thoughts. We also found a meme that integrated a fake account comment that involved a public person (Trăistariu) in a context that may be foreign to him and therefore altered reality. In this regard, we can say that even though no acute mobilization of the memescape was observed, memes have spread false narratives that could have influenced the opinions and attitudes of Internet users. Considering our second research question, (2) on the part that humor and satire play in the diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing of Romanian social movements, we believe that they serve as engaging tools that can attract attention and foster solidarity but also carry the risk of trivializing serious issues. The #RESIST protests, for example, demonstrated how humorous memes like the “gendarme on a chair” can effectively motivate and engage participants. The same humor sometimes undermines the seriousness required for strong diagnostic and prognostic framing. Thus, although humor can enhance motivational framing by making messages more relatable and shareable, it often weakens diagnostic and prognostic framing by not providing clear, actionable solutions.

When we discuss the differences in framing strategies of memes across social movements in Romania, (3) we think that they vary significantly, reflecting their unique challenges and focal points. Environmental movements like the Roșia Montană protests often focus on critiquing superficial activism without deeply engaging in diagnostic or prognostic framing. In contrast, anti-corruption movements like #RESIST and tragedy-focused movements like the Colectiv nightclub fire protests use memes to assign blame and foster solidarity more effectively, while they still struggle to articulate actionable strategies. These differences underscore the importance of context in shaping how memes frame issues and mobilize support.

The insights from our results align with and expand upon the existing literature, providing a nuanced understanding of how memes function in the online social movements landscape. The results demonstrate that memes are effective at highlighting specific issues and assigning blame, a notion supported by Gray and Goltz, who argued that digital media create narratives deviating from dominant hegemonic lines. In the Colectiv nightclub fire protests, the lighted candle symbol successfully conveyed systemic failures, aligning with the idea that memes capture and transmit diverse public perspectives (Gal et al., 2016). This parallels Milner’s (2013) description of memes (like the PSC) criticizing democratic governance by embedding cultural and historical contexts. Our findings confirm that memes in Romanian movements also use these strategies to challenge dominant narratives and highlight social issues.

At the same time, the humor and satire in memes play a significant role in engaging audiences, a point echoed by Milner (2012) and Shifman (2014), who note that memes convey complex ideas humorously and accessibly. The #RESIST protests showcased how humorous memes like the “gendarme on a chair” motivated participants and reflected Wiggins’ (2017) observation that emotional resonance can amplify a meme’s reach and impact. However, this humor sometimes undermines the seriousness of issues, which aligns with Denisova (2019), Nissenbaum, and Shifman (2018) views, who highlighted the mix of entertainment and serious commentary in memes. This dual role of humor stresses the need for a strategic balance to maintain the depth of a message while leveraging humor’s engaging qualities.

Finally, the results indicate that framing strategies vary across social movements. Environmental movements like the Roșia Montană protests critiqued superficial activism, often without deep engagement in diagnostic or prognostic framing. In contrast, anti-corruption and tragedy-focused movements like #RESIST and the Colectiv nightclub fire protests used memes to assign blame and foster solidarity more effectively. This difference aligns with Daphi, Le, and Ullrich’s (2013) findings that real-time global representation of images within social movements underscores memes’ power in mobilizing collective action.