INTRODUCTION

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), about one-third of the food produced for human consumption is wasted globally per year, totalling 1.3 billion tonnes of food waste (FW) annually (1).

FW has been described as the amount of edible food that is wasted due to human action and/or negligence, corresponding to unserved leftovers or plate waste (1). Recently, it has become a political priority, hence it constitutes an issue of utmost importance for global food security, with a direct impact on the population’s nutritional health status, the environment, and the economy (2). The impacts of FW on human health are complex, as the problem coexists with the oversupply of food in developed countries and food insecurity in developing countries (1).

Recent research has demonstrated high rates of FW in school canteens, particularly concerning vegetables, which aligns with findings indicating the reduced intake of these foods by children (3). Furthermore, according to the Portuguese National Food, Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (2015-2016), 69% of children under 10 years old consumed less than 400 grams of fruit and vegetables daily, failing to comply with World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, resulting in a substantial reduction in the intake of important nutrients (4, 5). These results highlight the need for interventions to promote its consumption among children since the poor intake of fruit and vegetables can result in a substantial reduction in the consumption of important nutrients provided by these foods (5).

Schools are fundamental environments where children spend an extensive amount of time and consume a significant amount of their daily meals (6). In this setting, food availability plays a major role in children’s eating patterns and the implications of FW can be aggravated since it can compromise children’s nutritional intake and healthy development (6). Besides the crucial role of food availability and appropriate nutritional quality for children’s health and growth, school meals represent a challenge to environmental sustainability and are an opportunity to tackle FW (7).

In Portugal, the municipalities are responsible for the provision and management of school meals in preschools and primary schools (8). Despite the efforts to comply with recommendations, studies have shown that FW values in Portuguese school canteens reach values up to 43% (9). To address this issue, it is crucial to consider and analyse the factors contributing to FW in each context. Several factors may contribute to FW in school canteens, including children’s age (10), the time available for the meal (11), the portion size (12), and the effect of ambience (13). Furthermore, improving the palatability of menus has been described as a strategy to increase school meal consumption among children, leading to decreased FW rates (14).

Reducing FW in this setting can promote children’s health status and adequate development, by ensuring their food consumption, appropriate nutritional intake and improving food consumption patterns (15). Moreover, since children are future consumers, improving eating habits and promoting awareness about FW implications from an early age can enhance the sustainability of future consumption models and patterns (15, 16). Therefore, the assessment of FW in school canteens is essential for the development and implementation of public initiatives that aim to reduce its implications for the health, the environment, and the economy (17).

To our knowledge, scientific evidence on FW assessments in public preschool and primary schools in Portugal remains limited and has not been investigated in the Algarve region yet.

OBJECTIVES

This study aims to assess and evaluate the FW produced at lunchtime in the canteens of five schools at Faro municipality, as well as analyse the association between the geographical location of the schools (urban and rural areas) and the amount of leftovers, plate waste and total FW.

METHODOLOGY

Study Design and Sample

The sample was obtained through a non-probabilistic and convenience selection. In the Municipality of Faro, the public school system encompasses eighteen schools across five school groupings, whereas ten schools serve both preschool and primary grades, from 1st to 4th grade (EB1/JI). To ensure sample representativeness, one EB1/JI of each grouping was selected, totalling five school canteens included in the study. The assessments were conducted over two weeks in July 2022, during three non-consecutive days in each school.

The assessment days were selected considering the inclusion of comprehensive data collection across the variety of foods served in school meals. Consequently, the protein source component was considered to ensure an equal proportion of both meat and fish dishes in the assessments. The vegetarian and compound dishes were not included in the statistical analyses due to their low representativeness. The geographical location of the schools was stratified based on the three main categories according to the Portuguese National Institute of Statistics: urban, semi-urban, and rural areas. Therefore, three schools located in urban areas and two schools located in rural areas were included. The meals of children aged between 3 and 10 years old who have lunch at the selected school canteens were included.

Food Service in the Schools

In every school, the lunch meal was composed of soup, a main dish (meat, fish, or vegetarian with vegetables and a carbohydrate source), bread, water, and fruit (or dessert) and was produced in each school's kitchen.

Data Collection

Food Waste Assessment and Classification

The assessment methodology consisted of separating and weighting the food produced and wasted by components: soup, carbohydrate source, protein source and vegetables (raw or cooked). Food weight measurement was performed in grams utilising a portable electronic kitchen scale (Libra® model W 75), with a capacity of 150.0 kilograms and an accuracy of 50 grams.

Firstly, the food produced was weighed right before serving. The containers were also weighted, and their weight was subtracted from the results at the end of the data collection. The plate waste was collected by the research team and placed in containers according to its composition. At the end of the meal distribution, unserved leftovers and plate waste were weighed separately. Water, bread, and fruit were not quantified due to the difficulty of controlling the quantity made available to consumers.

FW was classified according to the leftovers index (LI) and plate waste index (PI), using the categorisation of Vaz (18) for the LI (“acceptable”: up to 3%), whilst the categorisation of Aragão (19) was used for the PI (“acceptable”: up to 10%).

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics®, Version 26. Shapiro-Wilk normality test was performed.

Student's t-test was performed for variables with normal distribution and Mann-Whitney U test was performed for variables with non-normal distribution. The critical significance level considered to reject the null hypothesis was <0.05.

RESULTS

Fifteen menus were included in the study with a total of 2572 meals served, wherein 1879 meals (73.1%) were produced and served in urban area schools and 693 meals (26.9%) were produced and served in rural area schools. For the statistical analysis, two main dishes were not included as they were compound dishes (cod à Brás and hake fish with potatoes), which did not allow the assessment by components. The average FW found in all schools was 40.2% ± 7.3%, wherein 15.2% ± 7.3% were leftovers and 25.0% ± 5.7% were plate waste.

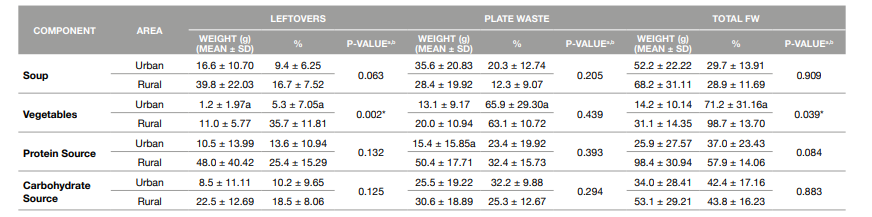

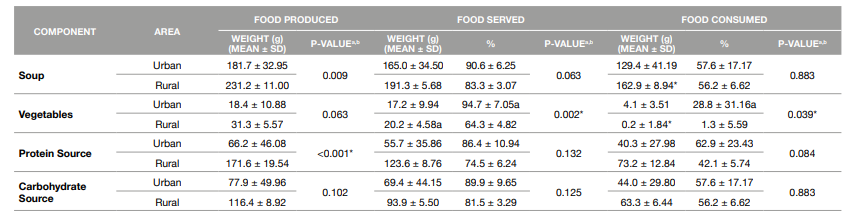

Regarding the total FW per capita, the highest percentage was found in the vegetables served in rural area schools, with a significantly higher value when compared to urban area schools (98.7% vs. 71.2%, respectively; p = 0.039). Furthermore, statistically significant differences were found in the vegetable leftovers per capita, with the highest percentage also observed in rural schools (35.7%, p = 0.002), as presented in Table 1. Concerning the food produced, it was found that more soup (p = 0.009) and protein source (p = 0.001) per capita were produced in rural area schools. Additionally, rural area schools served larger portions of vegetables per capita when compared to urban area schools. However, although the portion served was larger, we observed that children consumed much less (only 1.3%, p = 0.039) and it was less distributed when compared to urban area schools (64.3% vs. 94.7%, respectively; p = 0.002), as presented in Table 2.

No significant differences were found in total leftovers, plate waste and total FW according to the main dish type (meat or fish).

The plate waste and leftovers percentages of all meal components in both areas exceeded the acceptable limits according to Aragão (19) and Vaz (18), respectively. No significant differences were found in plate waste percentages between rural and urban area schools.

Table 1 Plate waste, leftovers, and total FW per capita, by component and location area

aStudent’s t-test was performed for the variables with normal distribution (soup, protein source and carbohydrate source components)

bMann-Whitney U test was performed for the variables with non-normal distribution (vegetables component)

*Level of significance (p) <0.05

Table 2 Food produced, served, and consumed per capita, by component and location area

aStudent’s t-test was performed for the variables with normal distribution (soup, protein source and carbohydrate source components)

bMann-Whitney U test was performed for the variables with non-normal distribution (vegetables component)

*Level of significance (p) <0.05

DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

FW has become a political priority in recent years, hence its direct impact on the economy, the environment, and the population's nutritional health status (2). In the school setting, these implications can be aggravated and compromise children’s nutritional intake and healthy development (6). Thus, this study aimed to assess and evaluate the FW produced at lunchtime in the canteens of five public primary schools in the Municipality of Faro.

Regarding the total FW, the average percentage found was 40.2%, which is above the results obtained in studies carried out in other Portuguese primary schools (9, 20, 21), highlighting the critical need for corrective measures. In this context, analysing FW separately as leftovers and plate waste can be a strategy to identify its specific causes and facilitate the development of effective corrective measures according to the setting.

In terms of leftovers, the average percentage found was 15.2%, exceeding the acceptable limit of 3% according to Vaz (18). The absence of standardised catering food portions can be an explanation for this result. Our study indicates that canteen workers did not adhere to guidelines, relying on the number of children and visually estimating meal ingredients.

Regarding plate waste, the average percentage found was 25.0% which is also above the limit of 10% according to Aragão (19). High rates of FW in the form of plate waste in school canteens are linked to several factors. Niaki et al. (10) demonstrated that younger children wasted more food. Therefore, children’s age must be considered for the establishment of food portions served to meet the nutritional requirements of each age group and is one of the determinants considered and presented in the new guidelines for Portuguese school meals (22). Additionally, assessing FW according to children’s age can facilitate the development of appropriate practices to encourage children to eat.

Another factor that may be associated with high rates of FW in the form of plate waste is the time available for the meal (11). In our data collection, it was observed that the meal duration in all schools varied between 30-45 minutes, which may not be enough time for children to eat their full meal and consequently increase FW rates.

Steen et al. (13) refers that noise level and stress-evoking conditions can affect the dining environment and consequently FW occurrence. In all schools, children from different grades had their meals at different times which helped to make the dining hall environment less crowded. Nevertheless, these conditions could be further assessed using dining hall capacity to make the environment less distracting, increasing the consumption of the food served and consequently decreasing FW in the form of plate waste.

Furthermore, it is understood that food appeal and tastefulness are determining factors for plate waste occurrence (23). In this context, the development of more appealing menus can be a strategy to promote food consumption and consequently minimise FW in the form of plate waste (14, 24). Additionally, analysing FW by components can facilitate the identification of foods with the highest rates of plate waste, which will enable their improvement or modification within menus (25).

Therefore, family eating patterns play a critical role in children's eating behaviours and preferences, which are carried over to school and may affect the acceptability of certain foods served in the school meal, particularly fruits and vegetables (26)

Comparing the results according to the schools’ location, significant differences were found between the amount of soup and protein sources produced in rural and urban area schools. Concerning the soup, it was found that larger portions were produced per capita in rural area schools. Nevertheless, it was observed that the amount served in both areas was lower than the Portuguese recommendation of 200 ml to 250 ml of soup per capita (27). Since promoting soup consumption among children can be a strategy to maintain adequate vegetables’ daily consumption, the inadequacy in the portion served represents a missed opportunity in terms of nutrient intake.

Regarding the protein source, the amount served in both areas was higher than the Portuguese recommendation of 41 grams per capita for preschool children and 49 grams per capita for primary school children (27). Nevertheless, the production was significantly higher in rural area schools, which resulted in larger portions of protein sources served and exceeded the recommendations (123.6 grams served per capita). The excessive availability of protein sources on the plate may interfere with the consumption of other meal components by children, especially vegetables. Furthermore, these findings raise sustainability concerns as protein source production is associated with higher financial and environmental costs (28).

Particularly about the vegetable component distribution, it was found that 95.0% of produced vegetables were effectively served in urban area schools, whereas in rural area schools, only 64.3% were served. This discrepancy highlights an inadequacy in the distribution percentage compared to the vegetable production in rural area schools, resulting in higher rates of vegetable leftovers.

Furthermore, vegetable consumption in rural area schools was notably lower compared to urban area schools. Considering that children eat a considerable amount of their daily meals at school, these results are worrying and can suggest that their daily intake is possibly below the WHO recommendation of 400 grams of fruits and vegetables per day (5). These findings are in line with the results from COSI/WHO Europe (2015-2017), which showed that, in Portugal, the daily consumption of vegetables by children who attended rural area schools was less frequent than children who attended urban area schools (29).

Particularly about vegetables, Miller et al. (12) suggests that larger portions can increase children’s intake. However, in rural area schools, the results demonstrate that although the quantity of vegetables produced and served per capita was higher, the consumption was lower. Therefore, increasing portions should not be encouraged as an individual approach, but rather in conjunction with interventions with children in the context of food education.

Given the results, the need for interventions is urgent since the rates of leftovers and plate waste in all components served in both areas exceeded the acceptable limits. In this context, the presence of a dietitian in schools enables the assessment of the characteristics of the canteens individually, so that FW can be reduced according to its determinant factors (30). Furthermore, the development of schoolbased interventions including health education (school curriculum, teaching, and learning), environment (schools’ social and/or physical environment) and partnerships (schools engage with families and communities) seems to have a positive effect on the dietary pattern of the children in the short and long term (31). Another approach can be promoting the continuous training of canteen workers to ensure compliance with catering food portions and reduce FW in the form of leftovers as it facilitates the standardisation of the service by developing strategies against the overproduction of meals, which is one of the main causes of FW on the stage of meals distribution (32). Additionally, focusing on integrated staff training to promote menu improvement, rather than only providing standard training, can enhance strategies to reduce FW in the form of plate waste (33).

There are some limitations to the current study. Firstly, the assessment was conducted during three days in each school, which may reduce the representativeness of the results throughout the school year due to the menu changes, since it is established according to the seasonal food criteria. Moreover, two main dishes were not included as they were compound dishes, and the rural area school’s representativeness was lower. Furthermore, due to the timing of the meals, it was not possible to perform specific assessments concerning children's age, and other school characteristics were not assessed. Nonetheless, several strengths can be highlighted, such as the inclusion of all school groupings of the Municipality of Faro; the scientific data production in this area which, to our knowledge, remains limited; and the methodology applied to assess the FW since weighing food by components appears to be more effective when compared to other methodologies, as suggested by Pedrosa (34).

CONCLUSIONS

The present study presents data about FW, in the form of leftovers and plate waste, in rural and urban area schools in the Municipality of Faro. Regarding the FW assessment in the canteens, the results found both in rural and urban area schools exceeded the acceptable limits. In this context, the implementation of corrective measures is urgent, especially concerning promoting school meal consumption among children, as it can directly interfere with their healthy development. The training and education of canteen workers must be simultaneously promoted, to help reduce FW in the form of unnecessary leftovers. When analysing the results, it becomes evident that there is a critical need to prioritise promoting children’s vegetable consumption, particularly in rural area schools.

Further research is required to develop corrective measures effectively aimed at reducing FW by promoting adequate food consumption among children and families, enhancing menu quality, and raising awareness among canteen workers about compliance with catering food portions. These initiatives will not only promote sustainability within school and home environments but also cultivate an educational environment for children regarding nutrition and sustainable consumption patterns.